I was seventeen courtships into humiliation by the time my father made his most audacious decision.

In Charleston parlors, they called me cursed.

The left side of my face carried the memory of fire—ridges knotted from temple to jaw, eye pulled downward, mouth slanted as if grief had become its natural resting place.

I learned early how pity sounds when it pretends to be kindness.

I learned how silence feels when men look in your direction and decide to aim their future elsewhere.

My name is Katherine Adelaide Thornton—Adelaide to everyone who matters—and I was seven the night our townhouse burned.

A candle toppled in the drawing room, curtains caught, then air itself seemed to turn into flame.

My mother pushed me toward a window.

A beam fell and became a boundary between life and death.

Her scream followed me into the years.

I woke three weeks later in my aunt’s house with half my face wrapped, hearing servants cry before I saw their reasons.

Judge Harrison Thornton was not a man accustomed to bowing to circumstance.

He had built a fortune in cotton speculation and slipped past political scandals with a strategist’s smile.

He sat the state’s highest bench and believed law—properly arranged—could unbend the world.

When I turned sixteen, he began inviting eligible men to dinner.

He set lamplight kindly, angled conversation toward my fluency in four languages, my music, my ability to discuss literature without widening eyes at Latin.

It never mattered.

Seventeen men, seventeen refusals, each polite enough to leave dignity intact and brutal enough to scrape it raw.

The last refusal broke something in my father.

The widower with three small children said I was everything a household needed in a mother, then stopped before the sentence that carried hope across a threshold.

“I cannot ask my children to accept…” he said, and let the rest sit in the room like a draft from a door you cannot close.

I found my father that night bent over a half-empty bottle, staring at a wall as if it had answers.

“You will not live at Edmund’s mercy,” he said finally, naming the cousin destined to inherit if no husband changed the inheritance path.

“I will not die leaving you defenseless.”

“What other choice is there?” I asked.

He did not answer.

He looked the way he looked before a ruling that would shock half the bar and make the other half grudgingly admit admiration.

Two weeks later, he called me to his study and said, “I found a solution.” He spoke of a man Charlestonians only knew by a headline: the enslaved dock worker who jumped from the pier three times into harbor water to haul drowning children back to breath while others stood rigid with risk calculations.

“His name is Daniel,” my father said.

“I purchased him.

I am giving him to you.”

I felt the room tilt.

“You cannot be serious.”

“I am.

The world refuses to give you a husband.

But the world is my business, and I can design a contract.” He set a document on the desk.

I read conditions more unusual than any case I’d seen.

For ten years, Daniel would serve as my protector and companion.

If he fulfilled the terms faithfully, he would be manumitted with a sum sufficient to begin anew.

Upon completion, my mother’s trust would pass to me—devised to be unreachable by Edmund’s grasping hands.

It was legal craftsmanship in a language blunt with injustice.

“You are asking me to own a human being,” I said.

“I am asking you to survive,” he answered.

“I am giving Daniel what no enslaved man has in South Carolina—a guaranteed, documented path to freedom.

I am giving you what most women never have—security that doesn’t depend on a husband’s whim.”

“I want to meet him,” I said.

“I won’t decide without speaking to him.”

They brought Daniel the next morning.

He was taller than I expected, wiry strong in the way men are when labor has sculpted their bones.

His face held intelligence without display; his eyes saw and measured; his voice carried the careful tone of a man who had learned that speaking the way the world expects can be a shield.

He looked at my scars and did not flinch or perform kindness.

He saw and moved past seeing.

It was the first mercy, and somehow the most important.

We sat across from each other in the parlor.

My father left us alone—the rarest kind of trust.

“He told you everything,” I said.

“He told me the structure,” Daniel said.

“He did not ask me what I think.” He said it without bitterness, as a fact.

“I am asking,” I said.

“Do you want this?”

“I want freedom,” he said simply.

“At the Rutledges, I lift and carry until my body gives out, then I lift again.

A shed crowded with men whose sleep smells like exhaustion.

No path beyond more of the same.

Your father’s offer is a line in the sand toward daylight.”

“And if I refuse?” I asked.

“I go back.

Or I am sold.

My life does not improve because of your scruples.” He watched my face.

“But I have questions too.”

“Ask,” I said.

“Can you live with owning me?” he asked.

“Because paper will say I belong to you.

Whatever our private arrangements, that is the public fact.” It cut clean because that is what truth does when wood is hard and blade is sharp.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“I know slavery is a horror.

I know participating in it would turn that horror into my daily act.

I also know my father is right.

I have no good options.

If I must be bound to someone, it should be to a person whose character I respect rather than a man who cannot see me past skin.”

“You respect me?” he asked.

“You have known me ten minutes.”

“You dove into water while others counted risks,” I said.

“That tells me something I value.”

He told me how he learned to read in fragments—his mother taught in a Virginia house where kindness had to hide itself from law; then sales scattered lives; then stolen newspapers became a lifeline because words can be owned by the mind even when bodies are not.

We talked about philosophy and survival and whether hope is an act or a feeling.

After three hours, the impossible became less impossible because connection sometimes rearranges what constraints feel like.

“I’ll agree,” I said, “but on conditions.” I told him I would never treat him as property.

I would never ask him to violate his conscience.

When he earned freedom, I would double my father’s promised sum.

And if, at any point, the arrangement became unbearable, I would help him escape North rather than bind him to suffering because paper says I can.

He stared at me a long time.

“I accept,” he said, “and add one condition of my own: if a decent marriage proposal ever comes, you take it.

I will find another path.

Do not close a door that could remake your life.”

“It will not come,” I said, and thought of seventeen dinners under warm light.

“But I accept your condition anyway.”

The arrangement began on the first of September.

The household murmured in scandal, the enslaved servants watched with the caution people develop when walls have ears, and Charleston whispered in corners because public outrage prefers safety more than courage.

Daniel moved into the room adjacent to mine.

He accompanied me to market and church.

He did not hover; he did not retreat.

He learned my limits and designed solutions like he had been inventing his whole life and the world had neglected to notice.

One morning, he fashioned a wire hook to help me button sleeves on my scarred hand.

At night, we read in the library.

His mind met mine and did not shy.

He took de Tocqueville and turned praise into critique because a country built on enslaved labor cannot claim democracy without accounting the debt.

He cracked ideas open like walnuts—precise, patient, clean.

He was brilliant in a way that did not perform.

He was kind in a way that did not pity.

Winter touched Charleston with its rare cool, and one evening Whitman moved from page to voice.

Daniel read: “For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.” The line hit like light under a door.

Tears surprised me.

He stopped.

“Did I offend?” he asked.

“You did the opposite,” I said.

“That sentence is beautiful and a blade.

Paper says you belong to me.

Reality says we belong to each other as equals because that is what a just world would say.”

He looked at me like people look when a truth they have held quietly is finally allowed to stand in a room without disguise.

“I care for you,” he said, careful and clear.

“Not because the contract requires me to keep you safe.

Not because freedom sits at the end of duty.

Because you are you.”

Every rule burned quietly around us.

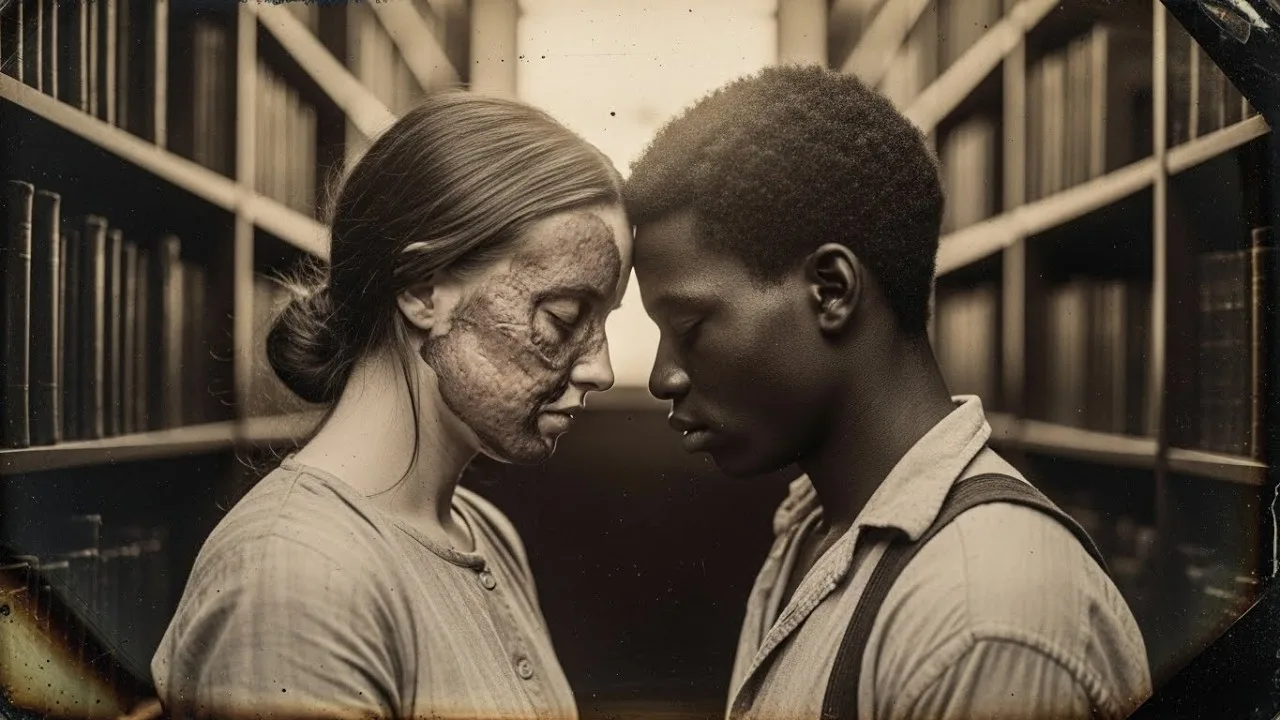

I said out loud what my heart had already done: “I love you.” We did not touch beyond leaning our foreheads together, the gentlest rebellion.

We agreed to proceed with care, to keep our love folded into the work of days until freedom remade the map.

For seven months, we lived inside careful, necessary restraint.

Then Edmund arrived with suspicion honed by greed.

He watched as predators watch when they smell story and money.

He saw us in the library, reading from the same page, my hand resting on his arm, intimacy carried in the relief of proximity.

“My God,” he said, performative and delighted, “you’re in love with your property.”

My father stepped from the hall like men step into fights they have prepared for all their lives.

Edmund named scandal and threat; he drew lines across danger; he tried to barter silence for inheritance.

My father told him to leave and told him how thoroughly he would bury him if he spoke.

Then he turned to us and asked for truth.

We gave it.

He looked tired and fierce and said, “Custom can be damned.

Law can be bent.

You leave tonight.”

He arranged papers and money and routes north.

We left at midnight through the back door of the life I had known since childhood.

We ran from slave catchers in Virginia, a pitchfork stabbed hay and found Daniel’s shoulder, and we learned how much pain love can hold without sound.

We crossed into Pennsylvania and discovered safety is a gradient, not a border.

In New Haven, infection almost took him, and a doctor brought mercy into a small room, lancing and cleaning while I held his hand and prayed in a language older than law.

We arrived in Boston on October third, our lungs full of exhaustion and air that did not weigh itself down with danger in quite the same way.

Abolitionists folded us into their network the way quilts fold warmth around bone.

Daniel found work and then respect.

I taught languages and music to children whose mothers valued skill more than symmetry.

In April of 1860, we married in a church that believed God blesses unions built honestly.

“Dearly beloved,” the minister said, and I cried because that phrase had never felt like it could belong to me.

We vowed in our own words.

He slid a simple ring onto my finger and kissed me in public, and the world did not end; it began.

We built a business in 1864—Freeman and Thornton Metalworks—crafting industrial work and adaptive devices for people whose bodies had been altered by war and accident.

My father saw his grandson and our joy twice before he died in 1863, having already hidden enough assets in careful places to make our start possible.

Lincoln’s assassination raked the country; our shop burned in 1865, and no one was charged.

Daniel’s hope buckled under ash.

I told him to rest while I fought.

The world had taught him to endure for too long.

It was my turn.

A letter from Frederick Douglass arrived like breath after drowning.

He asked to publish our story to show what could be built under pressure meant to crush.

We said yes, knowing attention carries heat.

Donations followed.

The shop reopened in July of 1866 stronger, guarded, focused on adaptive design.

Our devices showed at the Centennial Exhibition in 1876 and earned awards not just for innovation but for the specific kind of human kindness that says invention is for everyone, not just for those the world has decided deserve ease.

We raised four children: Harrison, who doctor’d veterans with hands capable and gentle; Elizabeth, who taught children whose schools had never known how to teach them; Samuel, who became an engineer because his father’s mind needed a continuation; Catherine, who became a lawyer and learned to bend law toward justice because she had watched her grandfather do it and her mother demand it.

We told our story in 1880 at an abolition commemoration because stories have work to do beyond their living.

We watched a young couple with mixed skin shades and steady hands find courage in our survival.

We became elders without planning to; we became proof you can be ordinary and revolutionary at the same time.

I am sixty now, writing this in October of 1895 on a porch warm with late sun.

Daniel’s hair has softened into gray.

Mine wraps the scars without pretending they are gone.

He still designs tools to make work possible for hands that tremble or refuse.

I still teach students who have been told their abilities cannot fit into the rooms schooling built.

We eat with children and grandchildren who carry in their voices a place that tried to deny their existence and failed.

“Do you regret it?” I asked last night, watching the sky decide between orange and blue.

“Never,” he said.

“Every struggle was worth having you.

Every rebuild taught us our bones.

Every fight proved what love can carry.”

If there is anything this life has taught me, it is this: survival is a practice and love is a choice you renew daily.

Paper said I owned him.

We wrote a different document—as partners, as equals, as people who stared down a world that misnamed them and decided to correct the language.

They called me unmarriageable.

They were catastrophically wrong.

They called him property.

They were thunderously wrong.

We were two human beings who refused to be defined by the worst words of our time.

We survived.

We loved.

We won.

News

Gideon Marshall the wisest slave in New Orleans, who deceived and destroyed seven plantation masters

There are stories that history tries to bury—too dangerous to tell, too unsettling to admit. They whisper a truth that…

Slave Finds the Master’s Wife Injured in the Woods — What Happened Next Changed Everything

The scream was so faint it could have been a fox, or a branch torn by wind. Solomon froze on…

The farmer promised his daughter to a slave if he planted 100,000 corn in 2 months—no one believed.

The summer heat in Franklin County, Georgia, did not simply sit on a man; it pushed. It pressed against lungs…

The Slave Woman With a Burned Face Who Haunted Slave Catchers Across Three States

They called her a ghost because it was easier than admitting they were afraid of a woman. The slave woman…

Master’s Son Noticed How His Mother Looked at the Slave Boy — One Night, He Followed Her

The plantation lay across the land like an old wound: rows of cotton stitched into the earth, a white house…

A Slave Boy Sees the Master’s Wife Crying in the Kitchen — She Reveals a Secret No One Knew

Samuel learned to live without sound. At twelve, he could pass from pantry to parlor like a draft—present enough to…

End of content

No more pages to load