In a shuttered bedroom heavy with laudanum and lavender, the quill did its work.

William Harrison Thornton—planter, patriarch, and emblem of South Carolina’s cotton aristocracy—signed away Magnolia Plantation, 5,000 acres of prime land and 200 souls’ labor, to the one man his world said could never own it.

Solomon Washington, enslaved for two decades, stood at the foot of the bed as ink set and a century of assumptions cracked.

The sound of nib on parchment traveled farther than anyone in that room imagined.

Not only into a Charleston vault and the county courthouse, but into the legal press, northern newspapers, militia orders, private diaries, and eventually, Reconstruction.

The Thorntons expected inheritance; the enslaved expected nothing at all; the county expected continuity.

Instead, the plantation became a test case, a scandal, and a map of how a single decision can expose the fault lines under a society’s polite surface.

—

Magnolia’s Ascent: From $50 to a Kingdom of Cotton

William was not born to white columns.

He rode south in 1810 from Virginia with ambition stitched into his coat lining—literally $50 sewn to cloth, figuratively a ledger for everything he’d never been given.

He learned land like a language.

At thirty, he ran a respectable farm.

At forty, he owned 300 acres and 20 enslaved people.

At fifty, Magnolia sprawled—5,000 acres of rich loam, a great house on a gentle rise, European furnishings that could silence old Charleston’s sneer.

He married well—Caroline Bowford, the social tether money couldn’t buy.

Four children arrived: Harrison, the heir apparent lacking the habit of labor; twins Margaret and Elizabeth, one a Charleston ornament, the other a reader with a hidden Philadelphia fiancé; Frederick, handsome and erratic, catastrophe when drunk.

William’s reputation hardened with wealth.

He rarely whipped at random; he preferred metrics to melodrama.

His ruthlessness was arithmetic.

Fail a quota, lose a family.

In a system built on cruelty, he made cruelty efficient.

Yet his library hinted at a mind that cracked its own shell—philosophy shelved beside ledgers, political treatises stuffed behind crop reports.

In the quiet hours when coughing interrupted sleep and autumn light thinned across rice fields, other ideas got in.

—

Solomon: From Kujichugula to Washington, From Capture to Competence

Before the Bowford dowry, before “Solomon,” there was a boy named Kujichugula on West Africa’s coast—nets, tide, songs.

At twelve, a ship.

One in three died crossing; he lived stubbornly.

In Charleston he was named anew; names were things planters took.

Placed as a house servant for quickness and numbers, he learned letters listening at thresholds.

When Caroline married William, the dowry included him.

At Magnolia, William put him in the fields to prove value—a principle he applied to man and mule alike.

Under a sun that burned identity into anonymity, Solomon carried an interior country where numbers, language, and memory kept him free where chain could not.

He married Esther, a cook, and built a family inside the boundaries of a world designed to dissolve them.

The blight changed his station.

When a fungal wave threatened a year’s cotton, the overseer panicked.

Solomon implemented a fix borrowed from observation, saving two-thirds of the crop.

William moved him into proximity—to the office, to problem-solving, to the zone where decisions get made and masks matter.

White men disliked taking instruction from a black man who was legally property, so Solomon pretended; he was deferential in public, decisive in fact.

If he asked for better food allotments or limits on whipping, he framed it as productivity, not mercy.

He gathered information because information is leverage under any regime.

His world judged him from two sides.

White men resented his competence.

Enslaved neighbors alternated respect and suspicion.

He used position to help where he could without setting off alarms he couldn’t silence.

Esther saw the rage and the plan beneath the calm.

He wasn’t reconciled; he was patient.

—

Heirs Without Stewardship: The Children and the Coming Vacancy

Harrison returned from the College of Charleston with posture, not practice—hybrid cottons that failed, sickly horses he called innovations, and a gift for blaming enslaved hands for his miscalculations.

Margaret married her way into older silver and permanent guest lists.

Elizabeth read northern women and wrote letters to a merchant’s son with abolitionist leanings.

Frederick drank, gambled, visited the quarters, and left faces turned toward shadow.

As William’s cough became diagnosis—consumption—the children treated Magnolia as showroom and quarry.

Harrison toured potential buyers.

Margaret measured drapes over a dying man’s body.

Frederick’s brutality spiked.

Elizabeth sat with books and thoughts she couldn’t speak aloud.

William asked about crop rotations; eyes glazed.

He asked about ledgers; they vanished from the room.

He watched from his bed as Harrison countermanded orders he didn’t understand and as Solomon corrected them quietly after the son rode away.

—

The Quiet Reassessment: A Sickroom Becomes a Court of the Mind

Illness creates altitude.

From the upper windows, William saw Magnolia as composite: rows moving under sun, smoke from the gin, wagons and hooves and the geometry of a system he had built.

With body’s betrayal came interest in other territories—Africa recalled by someone other than a trader, philosophy beyond profit, theology beyond tithe.

He summoned Jonathan Blackwood, lawyer and friend, and their conversations stretched late—documents reviewed, conscience weighed.

More visitors came: a discreet notary willing to earn the fee; a clergyman whose private doubts about slavery had never reached his sermons.

Catalyst arrived in the worst way.

Frederick entered Dina’s cabin drunk and entitled.

Thomas, her husband, tried to intervene.

A riding crop cracked across a face.

An overseer prepared a post.

William’s fury restored a slice of old strength.

Frederick left at dawn; Thomas moved to stables with a back in strips.

When rage cooled to breathlessness, William asked Solomon the question he’d never asked: If Magnolia were yours, what would you do?

Solomon tried caution and then surrendered to the calculation he’d built for twenty years.

He spoke of crop science that actually matched Carolina soil, incentives that didn’t require a lash to work, basic education that multiplied skill.

He mapped a system that did more than grow cotton; it acknowledged minds.

William listened and understood two things: his children wanted returns without stewardship; the man the law called property had already been steward for years.

—

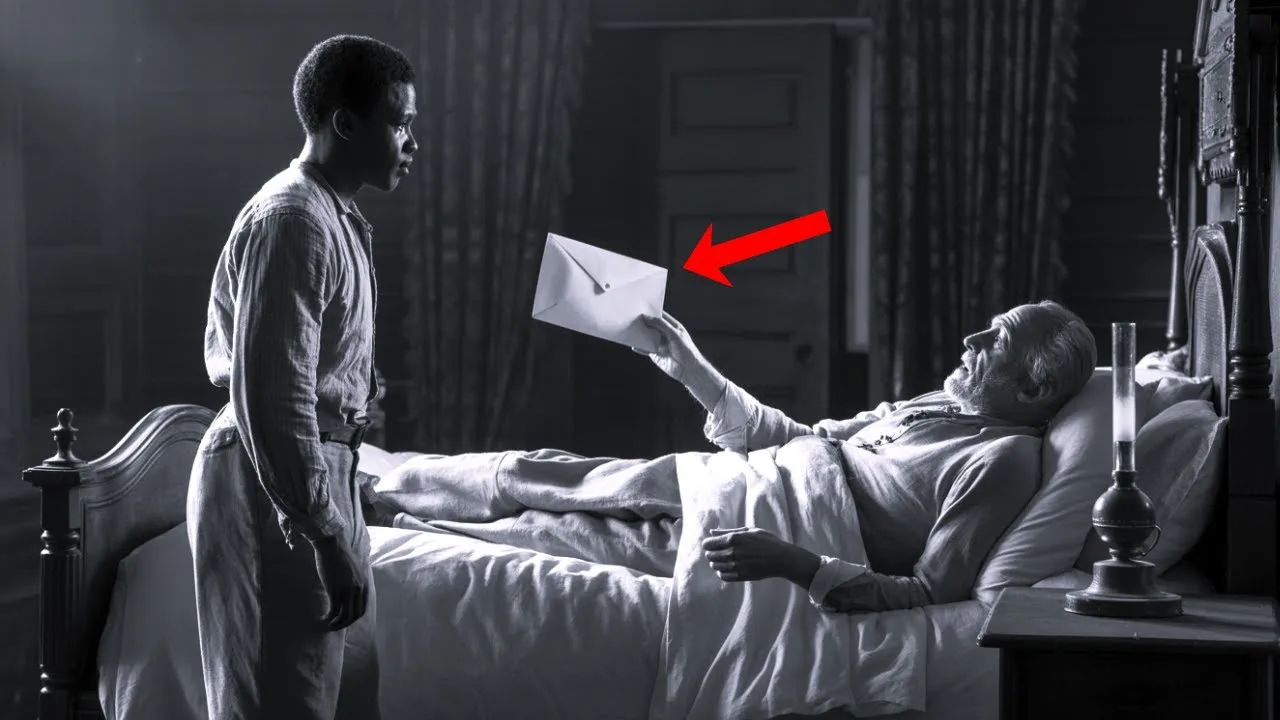

The Deathbed Scene: Ink, Witnesses, and the Sentence That Changed a County

October arrived hot enough to resurrect summer.

William refused opiates to clear mind for one last exertion of will.

The family assembled for a final meal at his bedside—social script performed over soup.

At seven, Blackwood arrived with a notary and Reverend James Porter.

Harrison bristled.

William, propped against pillows, found a voice sharper than laudanum had allowed in weeks.

He spoke of principles he’d never said aloud at a family table—worth as action and ability, not birth.

Harrison smiled prematurely.

Then the name dropped into the room like an iron weight.

Solomon Washington has managed this plantation in truth if not in name.

I have transferred Magnolia in its entirety to him, effective on my death.

Harrison called it madness and legal impossibility.

William raised a hand and detonated the next charge: manumission papers had already been filed; copies were with the governor’s office.

A trust instrument would hold assets if the law balked at direct ownership.

Blackwood had Judge Harrington’s provisional blessing.

The codicil arranged a sting: Caroline, a life income and the Charleston townhouse.

Each child, $1,000 paid in $100 annual installments—conditional on good behavior toward Magnolia’s new owner.

It was an insult tailored to genteel pride.

Frederick lunged; William’s rebuke cut him down.

The notary stamped the signature, the reverend witnessed, the air electrified.

Harrison promised a rope by morning.

Blackwood advised Solomon not to sleep under that roof.

Arrangements were already in motion—militia on the way for “order,” a sealed letter with a judge, a newspaper editor prepared to publish scandal at dawn.

William asked a last question—Was it worth it? Solomon’s answer was plain: Freedom is always worth the price; this was more.

Justice, perhaps even redemption, if such things exist where ledgers have long been confused with virtue.

—

Funeral Bells and Legal Blows: The First Hours of a Precedent

William died at dawn on October 4, 1857.

The plantation bell tolled, and sound carried into cabins and across county lines.

By noon, Blackwood read the will to a room where anger and disbelief had congealed into something more useful to the disinherited—strategy.

Harrison filed immediate challenges: incompetence, undue influence, racial impossibility.

Judge Harrington’s temporary order held the line—no change until hearing.

The state militia rolled up the drive to “prevent unrest,” led by Captain James Whitfield—a man more loyal to statute than to planter panic.

Solomon stood in the doorway of the parlor—neither family nor servant now, a liminal figure the law had not designed for.

He said little.

When Caroline demanded why militia boots muddies Magnolia’s drive, he answered: Not your property, ma’am.

The phrase dropped like a gavel.

That evening, in the yard where orders had rained down for years, he addressed the people who had harvested the wealth of others and would be expected to keep harvesting tomorrow.

He promised what he could create by policy alone—no whippings, no family separations, adequate provisions, schooling for children, wages that could accumulate toward self-purchase.

He did not promise mass emancipation he couldn’t execute without detonating the legal case.

Disappointment rippled and then quieted as the boundary moved a few feet in a field measured in miles.

—

Two Months as Master: Quiet Revolution by Practice

Magnolia ran.

Letters replaced trips to Charleston; written contracts built authority not pegged to skin.

Solomon refused the master bedroom and took an office instead.

He wore plain, well-made clothes—neither mimicry nor penance.

He documented everything.

A plantation’s output under black management is an argument; he collected exhibits.

Neighboring planters sent delegations to snarl at the gate.

The militia said no.

Pulpits delivered sermons about order dressed as theology.

Stores declined to sell provisions to Magnolia’s wagons.

Northern papers printed stories about the Black Planter of South Carolina, the phrase a provocation in itself.

Abolitionists clipped paragraphs; congressmen quoted them.

Solomon didn’t perform revolution; he practiced efficacy under a different rule set.

The change that matters in a system is often not a speech but the removal of a whip and the addition of a ledger that pays.

The Thorntons tried every lever.

Harrison litigated.

Margaret and Charles lobbied, whispering scandal into parlors and printing names into letters.

Frederick schemed from the bottom of a bottle.

Elizabeth did the opposite.

She came alone, sat across from the man who had once been asked to pour her tea, and said what the others wouldn’t: My father believed in competence.

He decided to force a conversation.

She warned of a governor’s order to send troops.

She warned and she leaked; presses in Philadelphia began to spin.

—

Standoff at Magnolia: Bayonets, Notebooks, and a Deal that Bought Time

State militia arrived at dawn in December.

They expected a gate to crash.

They found walls of paper.

Blackwood had assembled documentation; northern journalists had sharpened pencils inside the big house for days.

The workers stood in rows—calm.

It’s hard to tell the story of “rebellion” when the crowd is orderly and the books balanced.

Three hours of negotiation resulted in compromise.

Solomon would step back from daily management, appoint an acceptable white overseer, and retain ownership through trust pending court resolution.

He would relocate to Philadelphia under protection of the court’s order.

The plantation would remain productive; the precedent would remain alive.

It was not victory, but it wasn’t defeat.

Under the worst rules, a draw can be a win if it preserves the file.

—

Northbound: Philadelphia, Cold Streets, Warm Law

Winter in Philadelphia fought the Carolina blood, but freedom warmed faster than coal.

Streets had no columns; they had opportunities with conditions.

The Magnolia trust paid rent and school tuition.

Esther recalibrated a life that did not require listening for boots.

The children took to classrooms with a hunger that embarrasses the word “eager.”

Blackwood moved north temporarily to fight southern lawsuits from a safer docket.

Elizabeth’s fiancé, Edward Hullbrook, found himself an improbable ally to the man his future father-in-law had owned.

Legal motions hit calendars; hearings were set and reset.

The argument on paper was simple and incendiary—did a man have the right to assign wealth to merit rather than kin, and could that merit live in a black body?

—

The Hidden Compartment: A Journal That Recast Everything

Fire is a destroyer and a revealer.

In March 1858, flames chewed into Magnolia’s east wing.

Heat warped paneling in William’s study and exposed a metal box behind a bookcase.

Inside: a journal and letters from a younger William nobody at the table had met.

Courts sequestered them.

Copies traveled north.

The story changed categories.

As a young man, William loved an enslaved woman named Adeline on a neighboring plantation—rare not in occurrence, but in reciprocity.

When she conceived, he tried to buy her.

Her owner refused and sold her south—a cruelty used as leverage.

William hardened and married Caroline because alliances mattered.

Decades later, he recognized himself in a young man delivered with Caroline’s dowry—Solomon’s eyes and jaw mirrored in the glass each morning.

The journal documented a private crisis.

William never told Solomon.

He did what his system allowed without breaking his public life—he placed a son he wouldn’t acknowledge into positions that could become authority.

He built a path that only a deathbed signature could finish.

Expert witnesses authenticated ink and hand.

Elderly Charleston residents recalled rumors nobody had dared reduce to minutes.

The case turned from “eccentric planter gifts plantation to slave” to “father transfers estate to a son the law refused to name.” Scandal traveled faster, and differently.

Caroline withdrew behind drapes that couldn’t block this light.

Harrison grew reckless, dueled a man for an insult that wasn’t about the insult.

Frederick sailed away until funds thinned.

Elizabeth wrote to Solomon and admitted she had suspected some connection without naming it.

—

The Ruling: A Line Drawn Down the Fields

In June 1858, the court delivered compromise.

Law did what it does under pressure—it split the difference and pretended justice is geometry.

Caroline received the house and 1,000 acres for life, remainder to the children.

Solomon, through the trust, received 4,000 acres—the fields that made money, not just the rooms that housed memory.

Both sides could have appealed and prolonged spectacle.

Neither did.

The county exhaled shallowly.

The newspapers moved to the next fire.

The precedent settled like silt on river bottom—present, invisible, and consequential.

Solomon didn’t move back.

He was too smart to put his family under a roof where the law says black ownership is allowed but the neighbors prefer rope.

He hired an overseer he could control by contract and continued reform by remote—wages paid, families kept intact, schools maintained.

Cotton still moved; arrangements proved themselves through the only argument planters respected: profit.

—

The Return: An Address Without a Lash

In spring 1859, Solomon returned, briefly and with protection.

He stood again where he had once announced the end of whipping and the beginning of school.

He announced a plan that would have been revolutionary if the country were not already moving toward revolution: a five-year schedule to buy the freedom of every enslaved person on his portion of Magnolia, starting with families and the old.

Northern homes would be arranged for those who wanted.

Wages would be paid for those who stayed.

History chose a different route—muskets and proclamations, not ledgers and schedules.

But the intent landed.

People in the yard understood that in another timeline, change might have traveled quietly down rows instead of exploding across states.

—

War and Reconstruction: A Precedent Survives a Map’s Redrawing

War did what war does—scattered crops, burned buildings, emptied the South of wealth and the North of innocence.

The Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment mooted gradual plans.

Freedom arrived by fiat and fire.

After, there were questions constitutions hadn’t asked—how to arrange labor in a world where the price of a body is removed from the column.

By 1870, Solomon’s section of Magnolia looked different.

Big fields were cut into smaller plots; families leased and harvested for themselves, paying rent in cotton instead of paying with children.

A school taught letters once forbidden.

A small processing house added value before sale.

It was not utopia; it was a start.

The Thorntons’ section decayed in the way houses do when money dries and pride refuses to adjust.

Harrison died at Gettysburg wearing gray.

Frederick returned from Europe with debts and stories.

Caroline and Margaret kept rituals in a house that had fewer servants and more dust.

Elizabeth wrote letters to a man she had once feared and then admired.

—

A Life in Full: From a Boy Stolen to a Man Who Chose

Solomon died in 1883 at 88.

Obituaries ran from Philadelphia to New York and—most tellingly—one cautious paragraph in the Charleston Mercury.

They called him controversial; we call that a euphemism for “proof that the boundaries we draw are performative, not natural.”

His will emphasized the two things his life taught him matter most under duress: education and ownership.

Money went to children and grandchildren and to schools that taught black children the very disciplines planters had suppressed.

A foundation kept South Carolina land under disciplined management.

His funeral braided the past and future into a procession.

Black and white men stood near each other because mourning briefly rearranges the social order—remarks from northern reformers, attendance from southern names that once hissed his own.

He was eulogized as a test case that became a person.

—

Analysis: What a Deathbed Signature Exposed

– Stewardship versus inheritance: William’s last act separated the right to own from the accident of birth.

Magnolia’s profitability under Solomon’s management became evidence that stewardship is skill, not pedigree.

– Law as both barrier and tool: The manumission filed before the will, the trust vehicles, the judge’s order—legal engineering can carve channels even in a hostile landscape.

– Science of systems: Incentives, recordkeeping, education, crop rotations—Solomon won arguments not with slogans but with data.

Under unjust regimes, outcomes are the loudest politics.

– Community as infrastructure: The promise to end whippings and keep families intact wasn’t sentimental; it was an acknowledgment that stability is productive and dignity is efficient.

– Scandal as leverage: Publicity protected Solomon when militias arrived.

Northern journalists and a lawyer’s timing turned rifles into pens for a crucial morning.

– Memory as corrective: The journal and letters pulled a secret lineage into daylight, forcing a court to admit what custom had denied—that bloodlines don’t obey the fictions that support power.

—

Ethical Questions the Case Still Asks

– What do you owe a person you harmed when the system pays you for the harm? William’s will is a late answer—imperfect and real.

– Can justice travel through property? It did here, partially.

Ownership is not morality; it is power shaped by law.

He used it to pry open space.

– Is redemption possible in a ledger? A quill stroke didn’t erase bricks in the quarters or years in the fields, but it aligned a dying man’s authority with a truth he’d run from—kinship beyond category.

– What is the shape of courage? For William, it was a signature issued against his family’s wrath.

For Solomon, it was restraint when spectacle would have satisfied, and persistence when compromise looked like surrender.

—

Key Takeaways: Why This Story Endures

– One decision can turn a plantation into a courtroom where an entire society’s arguments are litigated.

– Competence is political under oppression because it challenges the premise that made oppression possible.

– Precedent matters.

A judge’s temporary order and a newspaper story together can save a life long enough to make an argument that outlives both.

– Gradualism is not cowardice when it is the only safe path; revolution is not theater when the other side has militias.

– Family secrets rewire law.

Bloodlines that cross categories put pressure on statutes until they admit their contradictions.

—

Closing: A Bedside, a Bell, a Door Left Ajar

On a hot October night, a man who had measured lives in bales tried to measure his own in something else.

He asked the only question that mattered to him at the end—was it worth it? The answer belongs to the man who survived what the system was designed to erase.

Freedom is always worth it, he said, and justice, if you can get it, is the interest paid on a very old debt.

On Magnolia’s grounds today, a small museum keeps the records—letters, ledgers, a copy of a will whose ink once made militia officers reconsider their orders.

The path from the big house to the quarters is short by foot and long by history.

Visitors walk it and feel how a bell can mean grief in one room and a beginning in another.

The Thorntons never saw it coming, because systems teach their heirs to stop imagining anything outside the system.

Solomon did, because survival required imagination more than obedience.

Between them, in a dim room where breath came in measured counts, a quill bridged a chasm it did not build, and left a door ajar for the country to walk through later—stumbling, fighting, but moving.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load