The plantation lay across the land like an old wound: rows of cotton stitched into the earth, a white house with proud columns, and a lattice of invisible lines telling everyone who could stand where, who could speak when, and who had to lower their eyes.

Ethan Witmore was raised inside those lines.

He knew which path was for the master’s family and which path bent toward the quarters.

He knew, because he’d been taught, that the order of things was fixed, natural, righteous: some commanded, others obeyed; some owned, others were owned.

He never wondered if the foundation beneath those rules might be rotten—until a single moment pried up the floorboards and let him see what had always been there.

It was late summer, the kind of day where the air pressed down hard enough to make thoughts slow.

His mother, Clara, handed him a basket: clean linens, salves, and better food than the kitchen allotted to the quarters.

She believed in charity—people said so often enough that it became part of the family’s reputation.

Visitors admired her gentle Christian nature.

Ethan’s father beamed when they did, as if kindness could be a ledger entry to balance the cost of iron chains.

Ethan believed that story because it was easier than pulling it apart.

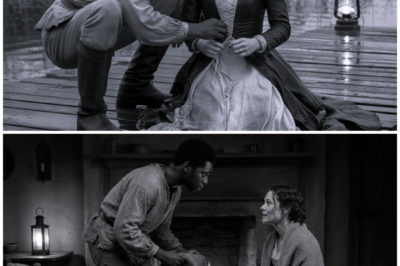

But that afternoon, crossing the hard-packed ground between cabins with the basket in his arms, he saw something he was not meant to see.

His mother stood in a doorway, her profile edged by sun, and she looked at one of the field hands with a gaze that didn’t fit anything he understood.

Isaac was young, maybe twenty, skin the color of polished walnut, shoulders broad from work, eyes steady—a quiet dignity that the fields were designed to crush.

People said he was strong and reliable.

Ethan barely noticed slaves as individuals before that day; they existed as a blurred background to his life.

But anyone would have noticed the look his mother gave Isaac.

It wasn’t the detached mercy of a mistress delivering supplies.

It wasn’t pity.

It wasn’t performative kindness.

Clara’s eyes held tenderness.

Raw, unguarded tenderness.

Ethan felt it like a shock to the skin.

He froze, half-hidden behind a stack of wood, the weight of the basket forgotten.

Isaac looked back at her, his face careful, knowing the risk of a moment that could be misread in a place where every look could be turned into evidence.

But his eyes answered hers.

Recognition passed between them—deep, aching recognition that did not belong in the world Ethan had been taught to accept.

As Clara lowered the basket, Isaac’s fingers brushed hers.

A heartbeat.

Three breaths.

No more.

But that touch spoke a language Ethan did not know yet; it had history, inside it, a familiarity born of time.

Clara pulled back quickly, the mask of propriety snapping into place like a door on a spring.

She left with measured steps.

The moment ended.

But it had happened, and once you see the crack, you cannot unsee the fault line beneath the paint.

For days, Ethan tried to explain it away.

Maybe his mother felt simple compassion.

Maybe he’d imagined more into a kind gesture.

His mind reworked the scene again and again, searching for interpretations that wouldn’t shatter the comfort of a life built on lies he hadn’t recognized as lies.

The arguments didn’t hold.

So he watched.

He saw the way Clara’s hand stilled when someone said Isaac’s name; how her eyes found him at a distance, scanning faces like a magnet tugging at filings; how her voice caught when she spoke about the enslaved people on the plantation, the words pushing at a wall she kept built inside herself.

He watched Isaac as well.

He noticed how the young man’s posture changed when Clara was near—shoulders taller, a shadow of hope passing across his face that could almost be mistaken for light.

He saw deliberate choices cross their paths: Isaac volunteered for work near the garden where Clara read in the afternoons; Clara delivered supplies herself on days when there was no practical reason to do so.

The dance was careful, a choreography inside a world where one wrong step could mean death.

The realization hit Ethan long before he admitted it out loud: his mother and Isaac were connected in a way that defied every law and rule he’d been taught to call moral.

He could name the consequences that would follow if anyone else saw what he saw—disgrace, exile, punishment beyond gossip—but the fear was not just about scandal.

What terrified him more was the truth pressed inside their glances: what stood between them looked like love, the kind of love that makes people willing to break the world they have to build the world they need.

If love could cross a line designed to separate souls, either the line was wrong or the whole world that drew it was.

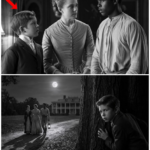

Three weeks later, Ethan’s father traveled to a neighboring plantation overnight, and the house felt lighter in his absence—as if the walls could finally exhale.

Clara said she was tired and would retire early.

Ethan watched her climb the stairs, her fingers trailing the banister.

He knew then what he had to do.

He waited, counted quietly to let her move in the house, and slipped out like a shadow, following at a distance.

The night was humid and close, the stars bright enough to make outlines.

Clara walked past the main quarters, past the cabins, toward the tree line at the property’s edge—the place where geometry’s clean lines of planted rows surrendered to the wild.

Nestled in brush that had gone untrimmed was a small cabin Ethan did not remember ever noticing.

It had the look of a forgotten thing.

The perfect place for a secret.

He moved to a side window, keeping to shadows, careful not to alert the dogs that patrolled the property by habit and teeth.

Candlelight spilled from inside.

He stood just far enough to see without being seen.

Clara sat with Isaac on a rough bench angled toward the small stove.

They spoke quietly—urgent, intimate, controlled.

“You shouldn’t have come,” Isaac said, concern underscoring the words.

“If anyone sees—”

“I don’t care,” Clara cut in, and Ethan flinched at the tone, because he had never heard that kind of fierce, simple truth in her voice.

“I needed to see you.

I needed to hear your voice.”

Isaac took her hand—tender, careful.

“We have to think through what we’re doing.”

“I’ve thought about nothing else for months,” Clara said.

“My marriage is a display case.

It does not hold a life.

I can’t pretend what I feel isn’t real.”

“You’re a married woman,” he replied gently, pain burying itself under a steady voice.

“You have a son.”

“I have a cage,” she said.

“I can either polish the bars or walk out of it.”

They held each other.

In that embrace, Ethan saw comfort and desperation meet, two people holding tight because there was no other way to stand upright.

It wasn’t a gesture that belonged to a fantasy; it belonged to people who understood that the world would not protect them if it noticed they were human.

When they separated, Clara said, “We’ll find a way.”

It wasn’t simply romance.

It was conspiracy, and it was freedom’s blueprint.

Love gave them courage; courage gave them plan.

The words Ethan heard slid into routes and safe houses and names of people in the North who would open doors at midnight and close them on the faces of men who knocked with dogs and papers.

Then Isaac asked the question that cut the boy behind the window open.

“And your son?”

Clara inhaled like breathing had just become work.

“I don’t know,” she admitted, voice cracking and then steadying.

“I love him.

But if I stay, I am choosing comfort over conscience.

He is his father’s son—raised in a house that tells him the floor beneath his feet is the ground God built.

I don’t know if he would come.

I don’t know if he could.”

Ethan pressed himself against the wood and felt his heart try to climb out.

When Clara said, “I love my son, Isaac.

But I love you more,” he turned away from the window and walked back through familiar paths like a man without skin, stunned and shaking, carrying a knowledge that burned and illuminated at the same time.

Three days passed like a fever.

Ethan didn’t eat.

He didn’t sleep much.

He walked through his chores as if someone else had borrowed his body.

Rage rose, then softened under understanding, then rose again.

He watched his parents at dinner—the way his father, Thomas, kissed Clara’s cheek without looking, a gesture practiced rather than felt.

He saw his mother’s shoulder flinch minutely.

The clarity of why she had turned away from that room to another person settled inside him heavy as lead and necessary as water.

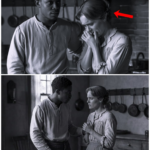

He found her in the garden under the magnolia’s armed shade and stepped out of the cool shadows he had learned to inhabit.

“Mother,” he said, and her hand flew to her chest at the surprise.

“We need to talk.

About Isaac.

About what you’re planning.”

The color drained from her face, washed back, then rearranged itself into a truth-telling mask that looked almost like relief.

“How long have you known?”

“Three days,” he said.

“I followed you.”

Clara closed her eyes briefly.

“Secrets do not stay hidden in houses like this,” she said softly.

“Why? you asked.”

“Because he’s not a slave,” she answered with calm fire.

“He’s a man.

He sees me.

Your father loves the idea of me.

Isaac sees the person.

I cannot live in a life designed to look beautiful and feel empty.”

“You’re going to leave,” Ethan said.

He knew the answer and asked anyway.

“You’re going to leave me.”

“That thought is the one that cuts,” Clara said, taking his hand and letting him feel the warmth of the mother he did not want to lose.

“I will not pretend otherwise.

But Ethan—answer me honestly.

Do you want to live this way? Do you want to spend your life arranging a system that you’re beginning to see stains every hand it touches?”

“I don’t know anymore,” he said.

He meant it.

He had never said those words out loud in his life; men like his father did not say them, they crushed them.

“Then come with us,” Clara said.

“Philadelphia.

There are people there who live by conviction, not hierarchy.

We can build a life where you are not asked to shore up someone else’s cruelty.”

“If I leave,” Ethan said, “I lose everything.

Father will disown me.

My name will be poison.”

“Yes,” she said simply.

“But you will have yourself.”

Before he could answer, gravel crunched on the path and Isaac’s figure emerged from the dark like a body built out of urgency.

“We have to leave,” he said.

“Tonight.”

“What happened?” Clara asked.

“An overseer has been watching me,” Isaac said.

“There’s talk of selling me downriver.

Your husband spoke carelessly to a man without your caution.

If they move fast, you’ll never find me again.”

“Then we go,” Clara said.

“Now.”

They turned to Ethan.

The moment pressed down hard enough to make bones feel thinner.

Ethan thought of Thomas’s voice and the ledger he’d learned to read, the weight of a plantation’s accounts balancing on backs.

He thought of the path north and his mother’s hand when she held his.

He heard himself say, “I’m coming.”

He understood, too, and the knowledge did not waver.

“If I don’t step now,” he said, “I may never find a way back to myself.”

Isaac’s hand settled on his shoulder—a gesture of gratitude that looked simple and meant everything.

“We move quickly,” Isaac said.

“There’s a safe house five miles north, run by Quakers.

If we reach it by dawn, we have a chance.”

“What do we take?” Ethan asked.

“Only what you can carry without slowing,” Isaac replied.

“Money if you can get it.

Documents that help our lives rather than shore up theirs.”

Ethan thought of his father’s study and the painting with a hidden lock behind it.

He knew the combination—men who believe in order seldom imagine their sons are watching.

“Give me thirty minutes,” he said.

“Meet me by the northern fence—old oak at the boundary.”

Clara pulled him into an embrace that felt both like childhood and choice.

“I love you,” she whispered.

“No matter what happens next, remember that.”

He moved through the house like someone negotiating with ghosts.

Thomas snored with the untroubled rhythm of a man whose conscience had never asked a question it couldn’t crush.

Ethan opened the safe—1863, the year the plantation began—and filled a canvas bag with as much cash as he could carry without turning it into a weight that would slow him.

He took documents that would open a door or an abolitionist’s heart: letters of introduction, deeds that proved the plantation’s wealth could be turned into a weapon against itself.

He took his father’s ledger—a record of theft and transactions that might one day testify against the idea that the family’s money was earned cleanly.

He packed spare clothes lightly, moved to the kitchen, and slipped through the back door by habit and design.

The dogs lifted their heads and wagged—they knew him.

He clicked his tongue soft, the sound handlers used to calm.

He slid across land he’d known since boyhood, gowns of cotton stretching beneath starlight in rows that suddenly looked like scars he had never named.

He had almost reached the fence when an overseer stepped from the shadows, whiskey sharp on his breath, rifle in hand.

“Where are you going, young master?” Garrett asked, suspicion and meanness twined in his voice.

“For a walk,” Ethan said, carrying privilege like a shield he hoped would let him pass.

“The house is suffocating.”

Garrett’s eyes dropped to the bag.

“Looks more than a walk.”

“My father trusts me,” Ethan said, playing the only card that might work.

He watched Garrett’s face tilt toward anger at the tone—the world inside men like Garrett thrives on deference.

A soft whistle floated from the trees—the kind boys use to call birds in jest.

Garrett turned his head a fraction.

Isaac moved out of darkness like a decision and brought wood down hard.

Garrett crumpled without sound.

Isaac grabbed Ethan’s arm.

“Run,” he said.

They vaulted the fence and dropped into brush, breath burning.

Clara waited where the boundary met wild, her face pale and set, bundle tight against her chest.

They ran until the shouts smeared into sound and dogs barked the alarm across land that suddenly felt like someone else’s map.

At a stream, Isaac led them into the water, following its course to hide the scent.

Cold bit into skin; current fought ankles.

They walked in the river’s song until pursuit softened behind them into distance.

Near dawn, a small cabin appeared inside a clearing so quiet it felt like a secret that had learned silence.

Isaac knocked three quick times, then two slow.

A woman opened the door, candlelight haloing her face.

“We’ve been expecting you,” she said, northern accent turning bless into fact.

“Quickly.”

Inside, the room held fire, table, chairs, and the kind of safety you can feel even when danger presses the walls.

An older man stood with kind eyes measuring risk against need.

“You’re the ones,” he said.

“I’m Samuel.

This is my wife, Margaret.

The basement door is hidden behind that wall.

You’ll sleep in daylight and move with night.”

They gave water and bread, clean clothes, and instructions in that steady tone people develop when they’ve repeated direction enough times to know that surviving depends on being understood.

Isaac laid out what had happened; Samuel filled in what would.

“They’ll put up notices,” he said.

“Descriptions, rewards for capture.

They’ll say the boy helped; they’ll say the woman abandoned her station.

The South will feel betrayed and righteous.

We will answer with movement and courage.

But you must trust the line.

One betrayal can break more than one life.”

Clara asked, “Can we reach Philadelphia?” not timidly but as someone confirming the direction of a map she could draw inside her chest.

“It is possible,” Margaret said, hand warm on Clara’s shoulder.

“We have seen people arrive.

We have seen people die.

You should know both truths.”

“It’s worth the risk,” Isaac said.

No one argued.

They left the next night inside a wagon’s false bottom, breath held against fear, hearts beating against boards.

Thomas, the driver, spoke calmly to patrols on the road, trading jokes about crops and storms while three bodies lay still on cedar planks.

At the next house—a widow named Elleanor who had turned grief into work—they ate beans and bread and learned the pattern repeated: move, hide, trust, pray, run again.

Two weeks later, after attics and root cellars, river ferries, and night-mapped fields, they reached Reverend James’s parsonage.

In the dim light of a single candle, Ethan talked with Samuel, a conductor who had been enslaved and learned to turn fear into purpose.

“You’re struggling with guilt,” Samuel said gently.

“It’s a good sign.

It means you’re awake.

But guilt is a room you can drown in if you don’t open a door into action.”

“How do you live with what was done to you?” Ethan asked.

“By refusing to let it keep happening without my resistance,” Samuel said.

“By telling truth, by moving bodies to freedom, by building a world where my grandchildren can look at a man like your father and not have to weigh how much pain his comfort costs others.”

Guilt did not vanish under those words; it changed shape.

Ethan realized that dwelling on the weight of his complicity would help no one.

What mattered was where he placed his body, his voice, his days.

Philadelphia rose like an idea becoming a place.

Streets filled with people moving without permission between race-defined lanes.

Some shops had signs meant to wound; some houses had lights meant to welcome.

They came to Katherine Morris’s boarding house—a Quaker widow who turned her inheritance into cover and food and beds.

“Sleep,” she said.

“Then we’ll find you work and rooms and names that will not bring dogs to your door.”

That night, Ethan lay between clean sheets in a room that felt like a future he had not thought belonged to him.

He pictured Thomas waking to an empty house, finding a safe empty of money and heavy with rage.

He pictured wanted posters in towns he would never see.

He pictured men riding with ropes and firearms.

He pictured his mother washing her face beside a lamp that did not signal danger, and Isaac folding his shirt on a chair without rehearsing an explanation for why he was there.

He fell asleep inside that strange mix of grief and hope, guilt and relief, peace and purpose.

Morning brought more than light.

It brought work assignments and meetings in rooms where people argued with passion about policies and street fights, church sermons and constitutional texts.

It brought introductions to men and women who had learned that resisting evil is not always a single dramatic act but often a series of small acts done bravely over years.

It brought questions about how Clara wanted to shape her days, how Isaac could earn what he needed for their life without selling labor in ways that bent him back toward plantations, how Ethan could begin to undo what his name meant by making his own a different kind of statement.

Months later, the fear did not disappear; it lived with them as a roommate that respected their boundaries most days and broke them on some.

They stayed alert, learned to read faces for danger, learned routes around neighborhoods that might bring trouble.

They built something anyway: a table where laughter came without being asked to hush, a room where a boy who had once believed in ownership learned to move without walking on people, a morning where a woman who had been held inside velvet expectation tied her hair back and stepped out into work she had chosen, an evening where a man who had lived ground down by someone else’s idea of his worth took off his boots and breathed without thinking about any man’s permission to do so.

Ethan looked back sometimes at the boy in the doorway of the cabin, watching love meet risk and wondering if he could hold both in his own hands.

He looked forward more often.

He started to believe that the world can be altered by the people who decide to move it.

Even impossible things can become lives if enough bodies stand up and say yes in the dark.

It began with a son noticing the way his mother looked at a slave boy.

It became a choice to follow her into a night where danger eats plans for breakfast and courage sets the table anyway.

It turned into a woman stepping out of a gilded cage, a man crossing a river to claim his own name, and a son deciding that his bloodline would not be his conscience.

Three souls pulled free from a place designed to keep them in; they moved north; they waited for the world to catch up.

News

A Slave Boy Sees the Master’s Wife Crying in the Kitchen — She Reveals a Secret No One Knew

Samuel learned to live without sound. At twelve, he could pass from pantry to parlor like a draft—present enough to…

Young Slave Is Ordered to Clean the Master’s Bedroom — He Finds the Wife Waiting Alone

Thomas had learned to live as a shadow. At nineteen, he could move from dawn to dusk without drawing a…

(1855, AL) The Judge’s Widow Ordered Two Slaves to Serve Her at Night—One Became Her Secret Master

The townspeople of Fair Hope said the Ashdown house never quite went dark after the judge died. On still nights…

Slave Man Carried Master’s Wife After She Fainted — What She Did in Return Shocked Him

The sun hammered the Georgia cotton fields until the air itself felt heavy. Solomon worked on, hands moving through the…

Slave Man Helped Master’s Wife Undress After She Fell in the Lake — Then This Happened

On a summer afternoon when the heat pressed down hard enough to quiet even the birds, a woman slipped at…

A Slave Man Protected Master’s Wife From Bandits — What She Did Next Left Him Speechless

Solomon kept his eyes pinned to the dusty road as he guided the team, careful not to glance at Mrs….

End of content

No more pages to load