It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back.

The air inside Morgan’s restoration studio smelled of old paper and chemical solutions.

She adjusted her magnifying lamp over the Victorian wedding portrait she purchased 3 days earlier at a South End estate auction.

The photograph, dated 1889, according to the seller’s notes, showed a young bride in an elaborate white gown standing rigidly before an ornate mirror.

Her expression unreadable in that distinctive way of 19th century portraits.

Morgan had bought it for $30, drawn by the exceptional quality of the image and the unusual composition.

Most Victorian wedding portraits were straightforward, bride and groom staring solemnly at the camera.

This one was different.

The bride stood alone, positioned at an angle that suggested she’d been uncomfortable, and behind her loomed that massive guilt-framed mirror, its surface slightly tarnished with age even in the original photograph.

She’d been working on restoring degara types all morning, her eyes tired from the meticulous work when she decided to take a break and examine her newest acquisition more closely.

Morgan switched on her high-powered digital microscope, the kind museums used for analyzing historical artifacts, and [bell] began scanning the image systematically.

The bride’s face came into sharp focus, young, perhaps 22 or 23, with dark eyes that seemed to hold something between resignation and defiance.

Her dress was exquisite, layers of silk and lace that spoke of considerable wealth.

The studio backdrop showed painted columns and drapery standard for the period.

Then Morgan moved the microscope to the mirror in the background.

At first, she thought it was a flaw in the photograph, a spot of chemical damage or a scratch on the glass plate.

But as she adjusted the focus and increased the magnification, her breath caught in her throat.

There, in the clouded reflection of the mirror, barely visible through the silver nitrate haze of age, was the bride’s back and her hands.

She was holding something.

Morgan’s pulse quickened.

She leaned closer, adjusting the light source, enhancing the contrast on her computer screen.

The object was small, metallic, catching light in a way that had survived more than a century of photographic degradation.

It looked like a key, ornate Victorian era, the kind that might open a jewelry box or a small safe.

But why would a bride hide a key behind her back during her wedding portrait? Why would she risk having it captured in the mirror’s reflection? Morgan sat back in her chair, her mind racing through possibilities.

In 15 years of restoring historical photographs, she’d seen countless wedding portraits.

She’d never seen anything like this.

This wasn’t an accident.

The bride had deliberately positioned herself to hide something from the camera while knowing, or perhaps hoping that the mirror might preserve evidence of what she carried.

Something about this photograph wasn’t just unusual.

It was wrong.

And Morgan needed to know why.

Morgan spent the rest of that evening photographing every inch of the portrait with her equipment, creating highresolution digital scans that she could manipulate and enhance.

By midnight, she had isolated the reflection in the mirror and used restoration software to remove as much of the age related distortion as possible.

The result confirmed her initial observation.

The bride was definitely holding a key, and from its design, she could just make out decorative scroll work on the bow.

It was likely from the late 1880s.

The next morning, she drove to the auction house in the south end where she’d purchased the photograph.

The building was a converted brownstone, its windows displaying an eclectic mix of furniture, paintings, and ephemera.

Inside she found Thomas, the elderly appraiser who’ sold her the portrait.

“Morgan,” he said warmly, looking up from a mahogany desk he was examining.

“Don’t tell me you found something wrong with that photograph already.” “Not wrong exactly,” she said, pulling out her tablet to show him the enhanced images, but definitely interesting.

“Do you remember anything about its providence? Where it came from?” Thomas put on his reading glasses and studied the images, his weathered face creasing with concentration.

That came from the Caldwell estate liquidation.

Old family, been in Boston since before the revolution.

The granddaughter was selling off everything after her mother passed.

Said she was moving to Arizona.

Didn’t want to deal with a house full of antiques.

Do you have contact information for her? I might.

He disappeared into his cluttered office and returned with a folder.

Here, Patricia Caldwell.

She left a phone number in case there were questions about any of the items.

He paused, studying Morgan’s face.

You really found something, didn’t you? Morgan showed him the enhancement of the mirror’s reflection, pointing out the key.

Thomas was quiet for a long moment, then whistled softly.

“In 30 years of doing this, I’ve never seen anything quite like that.” “You think it means something?” “I think someone went to considerable trouble to hide that key, while also making sure there was a record of it,” Morgan said.

“That’s not random.

That’s intentional.” She called Patricia Caldwell that afternoon.

The woman answered on the third ring, her voice hoarse and tired.

I’m sorry, Patricia said after Morgan explained who she was.

I don’t know anything about individual photographs.

That portrait was just part of a massive collection my mother kept in the attic.

Family pictures going back generations.

I didn’t even look at most of them.

Do you know who the bride in the photograph might be? Morgan asked.

There was a long pause.

If it’s from 1889, that would be around the time my great great grandmother got married.

Her name was Ellaner.

But I don’t know much about her.

My mother rarely talked about that side of the family.

Elellanar, Morgan repeated, writing it down.

Do you remember her last name before she married? Whitmore, Patricia said.

Elellanar Whitmore.

She married a man named James.

I think my mother had some of Ellanar’s things in a trunk somewhere, but I sold most of it.

I’m sorry, I can’t be more help.

After the call ended, Morgan sat at her desk, staring at the name she’d written, Elellanar Whitmore, 1889.

It wasn’t much, but it was a start.

She opened her laptop and began searching historical records, starting with Boston marriage certificates from 1889.

The Boston Public Libraryies genealogy section smelled like old books and floor polish.

Morgan had spent the morning navigating digitized records before deciding she needed to examine original documents.

A librarian named Sarah, who specialized in 19th century Boston history, helped her pull microfilm records of marriage licenses and newspaper announcements from 1889.

Whitmore, Sarah said, threading film through the reader.

That’s an old Boston name connected to textile mills, if I remember correctly.

Morgan’s attention sharpened.

Textile mills, large ones.

The Whitmore Mills operated in several locations around Massachusetts in the late 1800s.

Employed hundreds of workers, mostly immigrants.

Sarah paused as an image appeared on the screen here.

October 12th, 1889.

Elellanar Katherine Whitmore married James Harrison.

The newspaper announcement was brief but revealing.

It described Eleanor as the only daughter of Gerald Whitmore, prominent industrialist and philanthropist, and mentioned that the wedding took place at Trinity Church with a reception at the Whitmore family estate in Beacon Hill.

The groom, James, was identified as a businessman of good standing with connections to banking.

“Can you search for more articles about Gerald Whitmore?” Morgan asked.

“Anything from that period?” Sarah’s fingers flew across the keyboard, pulling up archive newspaper pages.

What emerged was a portrait of considerable wealth and influence.

Gerald Whitmore owned three textile mills in the Boston area, employed over 800 workers, and sat on the boards of multiple charitable organizations.

The society pages frequently mentioned the family, and Ellaner appeared in several photographs at fundraising events in Gallas.

But as Sarah scrolled through 1890 and 1891, the tone of the articles shifted.

In March 1890, a small news item reported labor disputes at one of Whitmore’s mills.

In June, [music] there was mention of an investigation into working conditions.

By October 1891, the headlines were more explicit.

Whitmore Mills under scrutiny.

Workers alleged fraud.

Morgan leaned forward, her heart racing.

Can you print all of these? The articles painted a disturbing picture.

Workers, primarily Irish and Italian immigrants, had complained to authorities about systematic wage theft, hours worked but not paid, deductions for supplies that were never provided, falsified time records.

What started as complaints escalated into a formal investigation by the Massachusetts Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Then in December 1891 came the breakthrough.

Industrialist Gerald Whitmore indicted on multiple counts of fraud documentary evidence surfaces.

The article was detailed.

Anonymous sources had provided investigators with ledgers, correspondents, and financial records proving that Whitmore had been systematically defrauding his workers for at least 5 years.

The evidence was so comprehensive, so meticulously documented that Whitmore’s lawyers couldn’t dismiss it.

He was arrested, tried, and ultimately sentenced to 8 years in prison, a shocking outcome for a man of his social standing.

“Anonymous sources,” Morgan whispered, staring at the screen.

She thought of the key in Eleanor’s hand, hidden behind her back on her wedding day in 1889, 2 years before the investigation began.

Sarah noticed her expression.

“You found something?” Morgan showed her the enhanced photograph on her tablet, pointing out the key in the mirror’s reflection.

What if Eleanor Whitmore was the anonymous source? What if she spent years collecting evidence against her own father? Sarah’s eyes widened.

That would explain why the evidence was so thorough.

She would have had access to everything.

His office, his personal papers, his business records.

She paused.

But why hide a key in a wedding photograph? Maybe it was the only proof she could preserve, Morgan said.

If anyone ever questioned where the evidence came from, if her role was ever suspected, this photograph would show she had the means.

That key opened something.

Probably a safe or strong box where she kept the documents before turning them over.

But she was getting married that day, Sarah said quietly.

To a man her father approved of.

Why would she go through with it if she was planning to betray him? That was the question Morgan needed to answer.

Morgan returned to her studio with copies of dozens of newspaper articles and began constructing a timeline.

Elellanar Whitmore married James Harrison in October 1889.

The labor complaints began in March 1890, 5 months after the wedding.

The formal investigation started in June 1890.

Gerald Whitmore was indicted in December 1891, more than 2 years after Elellanar’s marriage.

If Elellanor had been a collecting evidence, she’d done it methodically over an extended period.

But the question remained, why had she gone through with the marriage? Morgan needed to know more about James Harrison.

She returned to the library’s database and searched for his name in conjunction with Ellaners’s.

What she found was surprising.

After their marriage, there were almost no social announcements featuring the couple together.

In fact, after 1890, James Harrison’s name disappeared from Boston Society pages entirely.

She widened her search and found an obituary from 1923.

James Harrison, deceased at age 62, longtime resident of Portland, Maine.

The brief notice mentioned no children and listed Eleanor as his widow, but noted that she had remained in Boston.

They’d lived separately for over 30 years.

Morgan felt a chill.

This wasn’t the story of a happy marriage.

She searched for property records and found that James had purchased a modest house in Portland in 1891, the same year Gerald Whitmore was indicted.

Elellanar had remained in a townhouse in Boston’s Back Bay, property that had been transferred to her name alone in 1892.

Her phone rang.

It was Thomas from the auction house.

“I found something you need to see,” he said.

I was going through the Caldwell estate paperwork and discovered that Patricia sold a trunk of personal items to a collector in Cambridge.

I got his number for you.

He specializes in Victorian era correspondence and documents.

If there were any letters or diaries that belonged to Elellaner, he’d have them.

The collector’s name was Raymond, and he agreed to meet Morgan the following afternoon at his home, a converted carriage house in Cambridge filled floor to ceiling with wooden filing cabinets and archival boxes.

“Ellanar Whitmore,” he said, his eyes lighting up.

Yes, I purchased a trunk from that estate, mostly clothing and personal effects, but there were several bundles of letters.

He disappeared into his archive and returned with a leather portfolio.

I haven’t had time to properly catalog everything yet, but I remember these because of the dates, 1880s and 1890s, and the handwriting was remarkable.

Morgan’s hands trembled as she opened the portfolio.

Inside were dozens of letters, some in envelopes, others loose, all written in elegant Victorian script.

She carefully unfolded one dated August 1889, 2 months before Elellaner’s wedding.

My dearest Clara, it began, father has made his intentions clear.

[music] I am to marry James Harrison regardless of my own wishes.

He believes the connection to Harrison’s banking family will prove advantageous to his business interests.

I have no say in the matter.

My only consolation is that James, while not the man I would have chosen, is at least kind and has privately assured me that our marriage need only be one of appearance.

Morgan looked up at Raymond.

Can I photograph these? Take whatever time you need.

She spent three hours documenting every letter, her understanding of Elellanar’s story deepening with each one.

The picture that emerged was of a woman trapped by her father’s ambitions, but refusing to be powerless.

Elellanar had known for months before her wedding that she was being used as a pawn.

But rather than simply accepting her fate, she’d made a plan.

One letter, dated September 1889, just weeks before the wedding, was particularly revealing.

Dearest Clara, I have made a decision that may seem incomprehensible, but I believe it is the only moral path available to me.

I have spent the past year observing father’s business practices, and what I have witnessed sickens me.

The workers in his mills, good people who came to this country seeking honest work are being robbed systematically.

Father alters their time cards, inflates charges for materials, and pockets the difference.

I have seen the ledgers.

I have read his correspondence with his accountant, where they discuss these adjustments with casual cruelty.

I know I cannot confront him directly.

He would dismiss me, perhaps even destroy the evidence.

So, I have been copying documents in secret, keeping records of his frauds.

I have a key to his personal safe.

He does not know I made a duplicate years ago, and I have been removing papers one by one, photographing them and returning them before he notices.

The wedding approaches, and I will go through with it.

James knows the truth about father’s character, though not yet about my investigations.

He has agreed that our marriage will be one of mutual protection and independence.

Once I am married and established in my own household, I will be able to act without father’s direct control.

I am working with a lawyer who specializes in labor rights, a man father would never associate with, and when the time is right, when I have gathered sufficient evidence, I will deliver everything to the authorities.

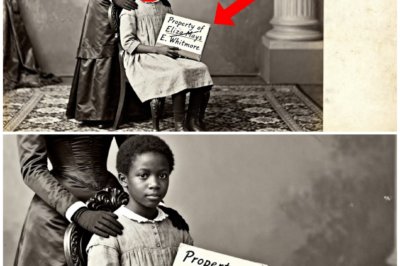

This wedding photograph next week will be my only record that I possess the means.

I will hold the key where father cannot see it, but where the mirror will capture its reflection.

If anything happens to me, if father discovers what I have done and seeks to silence me, at least there will be proof that I had access to his secrets.

Morgan sat back, overwhelmed.

Elellanar hadn’t just been a reluctant bride.

She’d been a deliberate spy, using her wedding day itself as a moment to document her access to evidence.

The key in the photograph wasn’t hidden carelessly.

It was positioned precisely so that only the mirror would reveal it, creating a permanent record that could protect her if her father discovered her betrayal.

The remaining letters detailed Eleanor’s methodical collection of evidence over the next two years.

She documented meetings with her lawyer, a man named Samuel Chen, who was building a case against her father with the material she provided.

She described the fear of being caught, the strain of maintaining appearances while secretly undermining her father’s empire and the growing horror as she uncovered the full extent of his crimes.

In a letter from November 1891, just before her father’s indictment, Ellaner wrote, “It is finished.

Samuel delivered all the documents to the Bureau of Labor Statistics yesterday.

I watched from my window as father was taken from his office this morning.

He looked smaller than I remembered, diminished.

Part of me feels the guilt of a daughter who has betrayed her father.

But the greater part knows that what I have done was necessary.

Those workers, Antonio with his three children, Bridget who sends money to her mother in Ireland, Luca who dreams of saving enough to open a shop, they deserved justice more than my father deserved protection.

James has been informed of my role.

He plans to move to Maine to establish a business there, away from the scandal.

We have agreed to maintain the appearance of marriage while living separately.

It is not conventional, but it is honest.

I will remain in Boston to face whatever consequences come.

Though Samuel assures me that as the source of evidence rather than a conspirator, I should be protected.

Morgan photographed the final letters, which detailed the aftermath, Gerald Whitmore’s trial, his conviction, and Ellaner’s quiet retreat from public life.

There were no more society page appearances, no more gallas or fundraising events.

Elellanar had effectively disappeared from Boston’s social scene, living modestly and according to the last few letters, dedicating herself to supporting organizations that helped immigrant workers.

Raymond watched Morgan work with quite interest.

But you found something significant, haven’t you? I found an extraordinary woman, Morgan said softly.

One who used her wedding day to create evidence of her own courage.

Morgan knew she needed more than Elanor’s letters to complete the story.

She needed to understand the impact of what Elellanar had done to find the workers whose lives had been affected by her actions.

The newspaper articles from 1891 had mentioned specific complaints and testimonies, and she spent the next week tracking down immigration records, census data, and union documents from the period.

At the Massachusetts Historical Society, she found transcripts from the trial of Gerald Whitmore.

The testimony was heartbreaking.

A man named Antonio Rossi described working 14-hour days at Whitmore Mills only to discover his wages had been systematically reduced through fraudulent charges.

“They say I owe for thread, for needles, for machine maintenance,” [music] he testified.

“But I never receive these things.

When I complain, the foreman tells me I will be dismissed and my family will starve.” Bridget O Sullivan, an Irish immigrant, testified about time cards that were altered to show fewer hours than she’d actually worked.

I mark my hours carefully in my own book, she said.

Every day I write the time I arrive and the time I leave.

The cards Mr.

Whitmore’s clerks keep never match my records.

Sometimes they show five or 6 hours less in a week.

That is food from my children’s mouths.

There were dozens more testimonies, all describing the same patterns of theft and deception.

And throughout the trial transcripts, references to documentary evidence provided by anonymous sources appeared repeatedly.

Gerald Whitmore’s own ledgers, his correspondence with [music] accountants, his instructions to foremen, all of it had been preserved and presented to the court.

Morgan found records showing that after Whitmore’s conviction, the Massachusetts legislature passed new laws requiring independent auditing of factory payrolls and establishing penalties for wage theft.

The reforms were directly attributed to the evidence presented in the Whitmore case.

One newspaper editorial from 1892 called it a watershed moment in labor rights, made possible by the courage of those who brought forth the truth.

But who had brought forth that truth? The public never knew it was Elellanar.

Morgan wanted to know what happened to those workers after the trial.

She spent days in immigration archives and city directories tracing names.

Antonio Rossi had used his recovered wages to open a small grocery store in the North End, which remained in his family for three generations.

Bridg Sullivan had saved enough to bring her mother and siblings from Ireland.

And her son eventually became a labor organizer who helped found one of Boston’s first trade unions.

These were real lives changed by Ellaner’s actions.

families that escaped poverty, children who received education, futures that became possible because one woman had refused to be complicit in her father’s crimes.

At the North End Historical Society, Morgan met with a genealogologist named Maria, who specialized in Italian-American family histories.

The Rossi family, Maria said, “Oh, yes, they’re well documented.

Antonio’s grocery store was a community landmark for decades.

His granddaughter still lives in Boston, actually teaches history at Nor Eastern University.” Morgan’s heart raced.

would she be willing to talk to me? Two days later, Morgan sat in Professor Isabella Rossy’s office at Nor Eastern, surrounded by books on immigration history and labor movements.

Isabella was in her 70s with sharp eyes and her great-grandfather’s strong features.

I’ve heard stories about the Whitmore Mills case my whole life.

Isabella said, “My great-grandfather never forgot what happened.

He used to tell us that someone had been watching out for the workers, someone brave enough to stand against a powerful man, but he never knew who.” Morgan pulled out her tablet and showed Isabella the enhanced wedding photograph, pointing out the key in the mirror’s reflection.

Then she showed her Ellaner’s letters, explaining what she’d discovered.

Isabella was quiet for a long time, studying the image of Ellaner holding that key.

When she finally spoke, her voice was thick with emotion.

“You’re telling me that this woman, this privileged daughter of the man who was stealing from my great-grandfather, she’s the one who saved him.

She spent two years collecting evidence,” Morgan said.

“She risked everything.

If her father had discovered what she was doing, she would have been destroyed.

Isabella finished.

Cut off, possibly institutionalized.

That’s what wealthy families did to inconvenient daughters back then.

She looked at the photograph again.

My great-grandfather used the money he recovered to start his store.

That store fed his family through the depression.

It put my grandfather through school.

It’s the foundation everything in my family was built on.

She touched the screen gently, tracing Ellanar’s face.

and we never knew we owed it to her.

Isabella insisted on helping Morgan find other descendants of the workers who’ testified against Gerald Whitmore.

“These families deserve to know the full story,” she said.

“And Ellaner deserves to be remembered for what she did.” Over the next month, they tracked down descendants across Massachusetts and beyond.

Some families had stayed in Boston.

Others had moved to different states following opportunities that their ancestors recovered wages had made possible.

Each conversation revealed another thread of impact extending from Ellaner’s actions.

They found Michael O.

Sullivan in Worcester, Bridget’s great-grandson, who worked as a union representative.

When Morgan showed him the photograph and explained Ellanar’s role, he sat silent for several minutes, his weathered hands folded on the table between them.

“My great-g grandandmother Bridget used to say that someone had been watching over them,” he finally said.

She called it providence, divine intervention.

She never imagined it was a real person who’d risked everything.

He looked at the photograph more closely.

What happened to Ellaner after the trial? Did she have a good life? That was something Morgan still needed to discover.

She’d found Ellanar’s letters up to 1892, but after that, the record went quiet.

Ellaner had lived until 1954, dying at age 87, but the newspaper obituary had been brief, just a few lines mentioning her birth date and noting that she’d been widowed in 1923.

Morgan went back to Patricia Caldwell, the woman who’d sold the estate contents.

I know you said your mother didn’t talk much about Ellaner.

Morgan said when they met for coffee in the back bay.

But did she leave any other personal effects? Diaries, later letters, anything from Eleanor’s later years.

Patricia frowned, thinking.

There was one thing, a small wooden box that my mother kept in her bedroom.

She never let me look inside when I was young.

Said it was personal family history.

After she died, I found it, but I didn’t know what to do with it.

She paused.

I still have it.

Actually couldn’t bring myself to sell something that clearly meant so much to her.

Two days later, Patricia brought the box to Morgan’s studio.

It was simple walnut, about the size of a shoe box with brass hinges that had tarnished with age.

Inside were more letters, photographs, and a leatherbound journal.

The journal was Ellaners, dated from 1893 to 1920.

Morgan opened it carefully, mindful of the fragile pages.

The entries weren’t daily.

Sometimes months passed between them, but they provided glimpses into Ellaner’s life after the trial.

January 1893.

I have begun volunteering at the North End Settlement House, teaching English to immigrant women.

It is quiet work, unnoticed, but meaningful.

These women remind me why I did what I did.

Yesterday, a young Italian mother thanked me for helping her write a letter to her family in Naples.

She does not know who I am, what I did to her former employer.

It is better this way.

June 1895.

I saw father today for the first time since the trial.

He is being released from prison.

His sentence reduced for good behavior.

He looked at me on the street and walked past as if I were a stranger.

I suppose I am.

We have nothing left to say to each other.

October 1900.

James wrote from Maine.

His business has done well, and he has found contentment there.

He asked after my welfare and enclosed a check to ensure I remained comfortable.

Our arrangement has proven wiser than a conventional marriage might have been.

We have preserved our dignity and our friendship, which is more than many married couples can claim.

The entries continued through the years, documenting a quiet life of service.

Elellanar never remarried, never returned to high society.

She worked with immigrant aid organizations, supported labor reform efforts, and lived modestly in her Backbay townhouse.

There were no grand gestures, no public recognition of her role in bringing down her father’s corrupt empire.

But there was something else in the box, a bundle of letters addressed to Elellaner, all from the 1890s and early 1900s.

Morgan carefully unfolded them.

They were from workers and their families, thanking an anonymous benefactor for help with rent, with medical bills, with funeral expenses.

Elellanar had been using the inheritance from her mother’s family to quietly support the people her father had harmed.

One letter from Antonio Rossi in 1897 made Morgan’s throat tighten.

To my unknown friend, my daughter has been accepted to the teachers college.

This would not be possible without your generosity.

I do not know your name, but I know you have a good heart.

May God bless you for seeing us as human beings worthy of help.

Elellanar had spent decades making amends for her father’s crimes, never seeking credit, never revealing her identity.

Morgan knew there was one more person whose perspective she needed.

Samuel Chen, the lawyer who had worked with Eleanor to build the case against Gerald Whitmore.

The letters had mentioned him repeatedly, but Morgan had found no records of his later life.

She searched legal directories, bar association records, and census data from the 1890s onward.

What she discovered was remarkable.

Samuel Chen had been one of the few Chinese American lawyers practicing in Boston in the 1880s, having graduated from Harvard Law School against considerable prejudice.

His specialty was labor law, and he had built his practice representing immigrant workers who couldn’t afford traditional legal counsel.

Working with Elellaner had been the biggest case of his career.

Morgan found an oral history interview conducted in 1948 when Samuel was 82 years old, archived at the Massachusetts Bar Association.

She spent an afternoon in their library listening to the crackling audio recording, The Whitmore case.

Samuel’s elderly voice said on the tape.

That case changed everything.

For labor law, for my career, for the workers who finally got justice, but people always ask me where the evidence came from, and I have never told anyone.

I made a promise.

The interviewer pressed him, but Samuel remained firm.

I will say only this.

The person who provided that evidence did so at tremendous personal cost.

They could have lived a comfortable life, could have ignored the suffering happening around them, but they chose differently.

They chose courage over comfort, justice over family loyalty.

That person deserves privacy and peace, not publicity.

The interview moved on to other cases, but Morgan’s mind stayed on that statement.

Samuel had kept Ellanar’s secret for over 50 years.

Even as an old man, knowing the historical value of the story, he’d honored his promise to her.

Morgan found Samuel’s obituary from 1951.

It mentioned his groundbreaking work in labor law and noted that he’d established a legal aid society to provide free representation to immigrant workers.

The society still operated, now called the Chen Legal Aid Foundation.

She visited their office in Chinatown, a modern building that still bore Samuel’s name on a bronze plaque.

The director, a young lawyer named Jennifer, was fascinated by Morgan’s research.

“We have some of Samuel’s personal papers,” Jennifer said, leading Morgan to their archive room.

“He donated them to the foundation before he died with the stipulation that certain documents would remain sealed until 2000.” “Those seals have been lifted now, but we haven’t fully cataloged everything yet.” Among Samuel’s papers, Morgan found detailed case files on the Whitmore trial, including notes on his meetings with Elellanar.

The notes were carefully worded, never using her full name, only referring to her as EW, but they documented the enormous risk Elellanar had taken and Samuel’s admiration for her courage.

One note from November 1891 read, “EW delivered the final documents today.

She was composed, but I could see the toll this has taken.

She knows what she is sacrificing.

her relationship with her father, her place in society, perhaps even her safety.

When I asked if she was certain she wanted to proceed, she said, “How could I live with myself if I didn’t? The workers who will benefit from her courage will never know her name, but they will feel the impact for generations.” Jennifer looked at Morgan with wonder.

“You’re saying Eleanor Whitmore, the daughter of the man Samuel prosecuted, she was his source.

She was more than a source,” Morgan said.

She was his partner in bringing her father to justice.

Jennifer pulled out her phone.

We need to document this properly.

This is part of Samuel’s legacy and Elellanar’s.

They should both be remembered.

Together, they began planning how to tell the story, not sensationally, but accurately, honoring both Elellanar’s courage and Samuel’s integrity in protecting her secret while she lived.

Morgan stood in her studio surrounded by the pieces of Ellaner’s story.

The wedding photograph with its hidden key, the letters documenting years of secret investigation, the journal entries revealing a life of quiet service, the legal documents showing the lasting impact of her actions.

She’d been working on this investigation for 3 months, and now she needed to decide what to do with what she’d found.

She thought about Isabella Rossi, whose great-grandfather’s grocery store had been founded with recovered wages.

She thought about Michael O.

Sullivan, the union representative whose great-g grandandmother had been able to bring her family to America because of Eleanor’s evidence.

She thought about all the descendants of those workers whose lives had been shaped by one woman’s decision to betray her father rather than be complicit in his crimes.

Elellanar had never sought recognition.

She’d spent her life making amends quietly, supporting the people her father had harmed, never revealing her role.

But she’d also left that photograph, that single piece of evidence showing the key in the mirror’s reflection.

Why? Morgan looked at the photograph again, studying Elellanar’s face with new understanding.

The expression she’d initially read as resignation now looked different.

There was determination there and sadness, but also something else.

Hope perhaps or defiance.

Helaner had positioned that key deliberately, knowing the mirror would capture it.

She’d created a record that would outlast her, that might someday tell her story when she no longer could.

It wasn’t about seeking glory.

It was about ensuring the truth survived.

Morgan called Isabella, Michael, and Jennifer along with Patricia Caldwell and invited them to her studio.

When they arrived, she’d arranged everything on her workt.

The photograph, the letters, the journal, the legal documents, the testimonies.

Elellanar left this photograph as evidence, Morgan told them.

I think she wanted the story told eventually, not for her own glory, but so that others would know what one person could do when they chose courage over comfort.

Isabella touched the photograph gently.

My great-grandfather’s store is gone now, but the building still stands.

It’s a community center.

What if we created an exhibit there? Not just about Eleanor, but about all of them.

The workers, Samuel, everyone who fought for justice.

Michael nodded.

The union I work for.

We could help.

This story isn’t just history.

It’s relevant now.

Workers still face exploitation, still need advocates, still need people willing to stand up to power.

Jennifer from the Legal Aid Foundation added.

And we could establish a scholarship in Ellaner’s name for law students who want to work in labor rights that would honor both her and Samuel.

Patricia, who’d been quiet, spoke up.

I have the key, you know, the actual key from the photograph.

It was in that wooden box with the letters and journal.

I didn’t realize its significance until now.

She pulled a small object from her purse, an ornate Victorian key, tarnished with age, but still beautiful, with scroll work on the bow, exactly matching the key in the photograph’s mirror reflection.

Morgan felt a chill.

This is what she held that day.

This is what she used to access her father’s safe.

They stood together looking at the key in the photograph, understanding that they were holding more than artifacts.

They were holding evidence of ordinary courage, the kind that changes history one difficult choice at a time.

Over the next two months, they worked together to create a comprehensive archive of Ellaner’s story.

Morgan meticulously documented every piece of evidence, every letter, every photograph.

Isabella helped research the families of the workers.

Michael connected them with labor historians and union representatives.

Jennifer worked with legal scholars to analyze the lasting impact of the Whitmore case on labor law.

Patricia donated Ellaner’s personal effects, including the key, to be preserved.

They decided against sensationalizing the story.

No dramatic headlines, no social media campaigns.

Instead, they created a careful, respectful presentation of Eleanor’s life and choices.

contextualized within the larger history of labor rights and immigrant experiences in 19th century Boston.

The exhibit opened quietly at the North End Community Center in a building that had once housed Antonio Rossy’s grocery store.

The exhibit was modest.

One room carefully curated with Eleanor’s wedding photograph displayed prominently alongside the key, the letters, and examples of the documents she’d helped collect.

Nearby were photographs and testimonies from the workers showing their faces and telling their stories.

Samuel Chen’s legal notes were displayed, honoring his role in protecting Elellanar while building the case.

The walls showed the timeline of the investigation, the trial, and the legal reforms that followed.

But what made the exhibit powerful wasn’t the artifacts.

It was the people who came to see it.

Isabella brought her extended family, three generations of Rossies, who stood quietly before Ellaner’s photograph, learning for the first time about the woman who’d made their family’s success possible.

We always knew someone helped great grandpa Antonio, Isabella’s elderly cousin said, tears in her eyes.

We never knew who.

We never knew it cost her so much.

Michael O.

Sullivan brought his union members who studied the exhibit with professional interest.

This is what solidarity looks like, he told them, pointing to Ellaner’s photograph.

Someone who had everything to lose, who chose to stand with workers instead of with power.

That’s what we’re supposed to be doing.

Law students from the Chen Legal Aid Foundation came in groups inspired by the story of Samuel’s courage and Ellaner’s determination.

One young woman, whose parents had immigrated from Vietnam, stood before the exhibit for almost an hour.

“My family came here for justice and opportunity.” She told Jennifer, “Stories like this remind me why legal work matters.” “Morgan watched these interactions from the side of the room, moved by how Elellanar’s century old choice continued to resonate.

The exhibit didn’t draw huge crowds.

It wasn’t meant to.

But the people who came were changed by it, and many returned with friends and family, spreading the story organically.

Three months after the opening, Morgan received a letter from a woman in California named Helen, who’d seen a small newspaper article about the exhibit.

“Helen explained that she was Elanor’s great great niece, descended from Eleanor’s younger brother.” “Our family never talked about Elellanor,” Helen wrote.

“We knew she’d caused some kind of scandal in the 1890s, that she’d testified against her father or something like that.

We were taught to be ashamed of her.

But after reading about the exhibit, I realized we had it backward.

She’s the one family member we should be most proud of.

Helen came to Boston, and Morgan spent an afternoon with her at the exhibit, showing her everything they’d discovered.

“Helen was in her 60s, a retired teacher, and she wept when she saw Ellaner’s journal entries.” “She was so lonely,” Ellen said quietly.

“She did this enormous, brave thing, and then she just lived quietly for decades, never telling anyone, never seeking recognition.” But she wasn’t entirely lonely, Morgan said, showing Helen the letters from workers thanking their anonymous benefactor.

She spent her life connected to the people she’d helped, even if they didn’t know it was her.

And she had Samuel, who kept her secret.

She had James, who gave her the freedom to live on her own terms.

Maybe that was enough for her.

Helen nodded, studying Ellanar’s wedding photograph.

The key in the mirror.

She wanted someone to find it eventually, didn’t she? I think so, Morgan said.

Not for glory, but for truth.

She wanted the story to survive.

As winter approached, Morgan returned to her regular restoration work.

But Elellanar’s photograph remained on her desk, a reminder of what careful attention could reveal.

She thought often about that moment when she’d first noticed the reflection in the mirror, that small glint of metal that had opened up an entire hidden history.

One afternoon, Patricia Caldwell stopped by the studio with a box of old photographs she’d been keeping.

I’ve been going through my mother’s things more carefully, she said, looking at them differently now, wondering what other stories might be hiding in plain sight.

They sat together, examining photographs of family gatherings, weddings, children, ordinary moments that might contain extraordinary secrets.

Morgan showed Patricia how to look closely, how to notice details that seemed insignificant, how to question what appeared obvious.

Ellaner taught us that, Morgan said, holding up the wedding portrait.

That the truth is often there waiting to be seen.

You just have to care enough to look.

The photograph of Elellanar Whitmore standing rigidly in her wedding dress with a key hidden behind her back remained at the community center exhibit.

Beside it, a small plaque readaner Katherine Whitmore, 1867 1954.

[music] In 1889, on her wedding day, she held a key that would unlock evidence of injustice.

Her courage in standing against her father’s corruption led to landmark labor reforms and restored stolen wages to hundreds of immigrant workers.

She spent her life quietly supporting the people her family had harmed, never seeking recognition.

This photograph, with its reflection in the mirror, was her only record, left not for glory, but as testimony that one person’s choice can change countless lives.

The key itself rested in a case beside the photograph, a small piece of tarnished metal that had once opened a safe full of secrets and now stood as a symbol of courage, integrity, and the power of choosing justice over comfort.

And somewhere in Morgan’s studio, carefully preserved in archival materials, were dozens of other Victorian photographs waiting to be examined.

[music] Each potentially holding its own hidden story, its own moment of truth captured in silvery reflection, waiting for someone to care enough to notice.

Elellaner’s legacy wasn’t just in the laws that changed or the lives that improved.

It was in the reminder that history isn’t only made by the powerful in public, but also by quiet individuals who make difficult choices and leave small traces of evidence for future generations to find.

The photograph was just a wedding portrait until someone looked closely enough to see what the bride was hiding behind her back.

And in that small act of observation across more than a century, Elellanar’s courage was finally recognized and honored.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

This 1868 Portrait of a Teacher and Girl Looks Proud Until You See The Bookplate

This 1858 studio portrait looks elegant until you notice the shadow. It arrived at the Louisiana Historical Collection in a…

End of content

No more pages to load