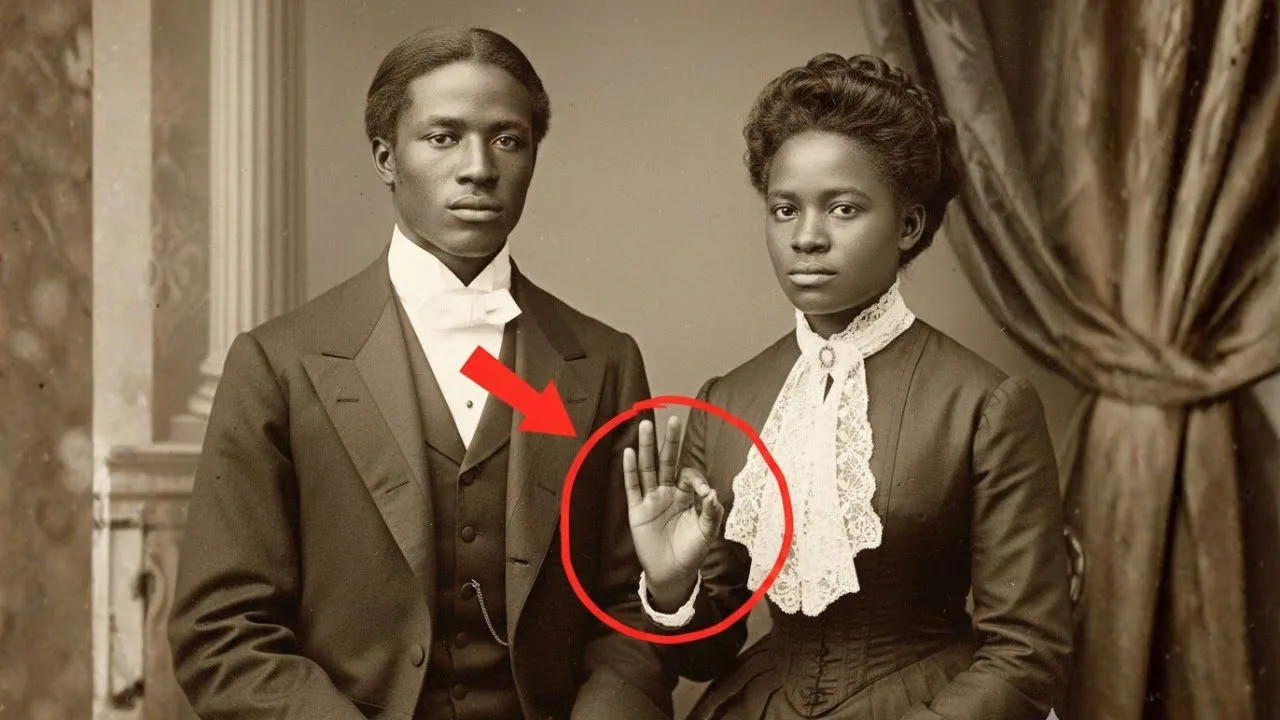

It was just a portrait of a young couple—until a historian looked closely at the woman’s left hand and saw what had been waiting for 129 years.

In April 1895, Thomas and Sarah posed in a Charleston studio against a painted parlor backdrop, dressed in their best: the man’s suit a shade too large, the woman’s high-neck lace fitted to the fashions of the decade.

The photograph is precisely what you would expect from the era: posture, decorum, solemn faces in the language of early American portraiture.

But the small geometry of Sarah’s fingers—thumb touching forefinger, the other three angled upward and apart—does not belong to etiquette.

It belongs to a hidden lexicon.

And once you see it, the portrait stops being a picture and becomes testimony.

Dr.

Maya Richardson found the photograph the way remarkable stories always begin—by almost missing them.

She had been sorting donations at the Charleston History Center for three hours, moving across stacks of sepia cards and cracked albumen prints, families who address a camera as if addressing time, the sternness of their expressions a product of the technology and the age.

On the back of one mount, a faint pencil line read: “Thomas and Sarah — Charleston, South Carolina — April 1895.” She almost set it aside.

Almost.

A small voice—curiosity learned from long practice—asked her to stay with it.

She shifted her lamp and took up a magnifying glass.

Sarah’s face was controlled into a polite blankness, a look Black women in the 1890s knew how to make under the gaze of a public that judged them harshly.

The right hand was relaxed.

The left hand was not.

Richardson knew enough code to be alarmed.

She had seen hand signs in the material culture of the Underground Railroad—subtle cues embedded in textiles, gestures in photographs, arrangements of objects meant to signal danger or need without words.

But the date insisted on a contradiction: 1895, thirty years after the war.

Why would a Black woman, nominally free, embed a distress signal in a formal, expensive studio portrait? She photographed the image, zoomed in, checked against her notes.

This was not pose or accident.

It was intent.

An encoded plea embedded in an image meant to outlast the people inside it.

If a story is going to move from hypothesis to history, it needs to be held up against records.

Richardson went home to her small apartment overlooking the harbor and worked the basics first: names, place, year, the tedious search that separates romance from fact.

The 1900 federal census offered the first anchor: Thomas, 29, builder; Sarah, 26, listed without occupation, married seven years, living on Trade Street.

It framed them as newlyweds building a life in a hostile decade.

Then the anchor shifted.

The 1910 census listed Thomas alone, still a builder, now 39.

His wife did not appear.

Death records in Charleston County from that era are inconsistent at best, callously incomplete at worst, especially for Black residents whose lives officials often considered not worth recording.

But the search returned a specific, brutal line: “Sarah, wife of Thomas, died August 1895, age 26.

Cause: complications from injuries from a fall.”

The words were a familiar kind of lie.

In the 1890s, Black deaths in white households were often erased with causes that did not explain bruises.

“Fall” covered a multitude of sins.

Richardson, unable to sleep, was on the History Center’s steps at dawn, waiting for the guard to open, and went straight to the donation file.

The photograph had arrived as part of a house clearance; the liquidation company had emptied an attic on Trade Street and sent over boxes of images nobody wanted.

“Most of it went to the trash,” the woman on the phone said.

“History center only took the pictures.” It is the kind of sentence historians learn to bear.

Richardson asked for access to the house before the new owner took possession.

Inside, the smell of damp wood and dust felt older than the furniture.

The attic was airless.

Shattered chairs, insect-eaten clothes, trunks of family residue.

In the back corner behind a broken rocker, a wooden box labeled “Photographs, various” held what the company had not bothered to sort: loose papers, letters, bills.

Most were ordinary.

One was not.

An envelope addressed to Mrs.

Elizabeth Morrison, September 1895.

The letter inside, written in careful script, reported a maid’s death: “Dear Mrs.

Morrison, I am writing to tell you about a very sad matter concerning your former maid, Sarah… she suffered a terrible accident in August and has since died.

Her husband Thomas has asked if you might have any information about Sarah’s family… he can be reached through Reverend Patterson at Emanuel Church.” The polite tone concealed the force of the story.

It placed Sarah in the Morrison household—an old Charleston family; it linked Thomas to a pastor; it hid the word “fall” behind elegance.

If you are going to chase truth in Charleston, sooner or later you walk to Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church on Calhoun Street.

The white spire rises above history and pain.

The church has stood through fire and hatred, banned, rebuilt, reopened, and continues to hold names and memories official records refuse.

Reverend Marcus Johnson led Richardson downstairs to the archive storage, warning that earthquakes and flames had taken their share of the church’s past.

The leather-bound volumes yielded what they could.

Marriage entry: “Thomas Daniels and Sarah — April 7, 1893.” No family name for Sarah, a common reality for people whose parents had been enslaved or whose names had been taken from them by force.

Funeral entry: “August 28, 1895 — Sarah Daniels, wife of Thomas — Magnolia Cemetery, Black section.” And in a margin that mattered as much as any official line, Reverend Patterson’s cramped hand: “Inquiry from T.

Daniels regarding marks on deceased.

No answers provided.

Matter closed.”

You learn to hear what margins say.

The note was not normal bookkeeping.

It recorded a husband’s doubt and the refusal of inquiry.

In 1895, a Black man who asked white authorities to investigate a white household risked his life.

Reverend Johnson studied the portrait and the woman’s hand sign long enough to let silence do its work before he spoke.

He had seen variations of it in oral histories and the kind of documents that survive in family trunks.

“Domestic service could be dangerous,” he said.

“Young women working in white homes had no legal protection.

Signals persisted even after emancipation because threat persisted.”

The logic of events narrowed and sobered: portrait in April; hand signal embedded; death in August; a husband observing bruises and wrist marks that did not match a fall.

The next step was to understand the Morrison household.

The Charleston County library’s third floor has a quiet gravity—microfilm readers humming, researchers bending over ledgers.

James Morrison, cotton trader, wealth built on forced labor before the war, diminished but durable after.

His wife, Elizabeth.

Their son, Robert, 28—society pages listing charitable events, parties that kept reputations polished.

And then a line in July 1895 that felt like a door slamming: “Robert Morrison… left last Saturday for a long trip to Europe… expected to stay abroad for the rest of the year.” Wealthy Charlestonians traveled in winter.

A summer departure without follow-up reports smelled like the management of scandal.

In January 1896, Robert returned and resumed his position without detail.

Richardson wrote a timeline in her notebook and asked hard questions aloud in an empty archive room.

April 1895: Thomas and Sarah pose; Sarah makes a sign.

March 1895: a handwritten courthouse note documents a $200 “advance payment to Thomas Daniels, builder, for household repairs and changes.” In 1895, that sum for a Black tradesman was extraordinary.

Was it compensation for work? Or a transaction designed to move Sarah out of the house through marriage and reduce risk to the Morrison family? July 1895: Robert leaves the country.

August: Sarah dies.

January: Robert returns.

The sequence invites a specific suspicion.

The cause of death invites a word the official records avoid.

A historian’s job is not to accuse but to document.

Richardson returned to Emanuel for committee minutes.

Black benevolent societies recorded the deliberations and aid that kept members alive when the law would not.

The page dated September 15, 1895 reads like a body blow.

Thomas asked for an investigation, described an absence of previous illness, fear in Sarah’s final weeks, unspecified threats, bruises inconsistent with a fall, wrist marks, defensive wounds.

The committee recommended “given current climate and danger to Black citizens pursuing complaints against white families,” that he “not push the matter further,” raised money for the funeral, provided $45 to help him start a workshop in Columbia, and advised immediate departure from Charleston.

Reverend Johnson’s explanation was controlled and honest.

The committee had saved the only person they could save.

In 1895, justice for a murdered Black woman at the hands of a wealthy white man was not available.

The cost of demanding it was a lynch mob.

The church scaled courage to survival and recorded truth in a ledger line the courthouse refused.

If you are going to follow a man’s grief north, you drive out of Charleston and watch the land change.

Two hours takes you through flat coast toward pine and red dirt.

A contact at Bethel AME Church in Columbia—Pastor Ruth Williams—welcomed Richardson and placed a worn leather notebook on the desk.

Reverend Thomas Nathaniel’s record book documented arrivals, aid, work, and sorrow between 1893 and 1905.

October 1895: “Thomas Daniels, builder, arrived from Charleston with a letter from Reverend Patterson of Emanuel AME.

Brother Daniels has suffered great loss.

Wife Sarah murdered by White family.

Death wrongly recorded as accident.

Brother Daniels sought justice but forced to flee due to threat of mob violence.

Welcomed… Provided room… Committee raised money to help establish workshop.” If there is a moment for the word, it is when it appears in a pastor’s hand.

Murdered.

Richardson read the line aloud, because sometimes saying a word breaks its denial.

The Columbia records showed a man upright in practical ways—fixing pews in 1896, building cabinets in 1897, attending to church work—and broken in private ones.

March 1896: “Brother Daniels struggles with bad dreams… speaks of his beloved Sarah… failure to protect her… assured him her death was not his fault, but he cannot forgive himself for living.” In 1898 he left for Chicago, joining an early wave of Black southerners heading north for safety, work, and the chance to breathe.

Pastor Williams, with four decades of ministry behind her, said what Richardson already knew from the pages she held.

Thomas carried Sarah like weight.

He did not stop mourning.

He likely did not speak her name outside spaces where it was safe—which is to say, almost nowhere.

A portrait is a way to speak to the future.

Richardson wrote for the Journal of Southern History, prepared the apparatus of evidence—high-resolution images, census records, church minutes, house ledgers, newspaper clippings—and titled the piece “Hidden in Plain Sight: Sarah Daniels and the Silent Testimony of the 1895 Charleston Photograph.” The review board said yes six weeks later.

But academic papers do not reach the people who need to learn how to read photographs for distress.

Public history does.

Richardson approached Dr.

Patricia Holloway at the Charleston History Center with a proposal for an exhibit that would teach viewers to see encoded messages in historic images and confront the reality of violence against Black women in the postwar South.

The exhibit opened in October—129 years after Thomas fled.

It did not shout; it argued with quiet authority.

The portrait hung beside a carefully enhanced print that showed the hand sign without altering the image.

Panels explained the signal’s history and the context of domestic service abuse.

The Emanuel ledger’s margin and the benevolent minutes were displayed with transcriptions, because legibility matters.

The Columbia record book was reproduced for public viewing.

The Morrison household was contextualized with caution, because proper history differentiates between moral clarity and modern vengeance against the long dead.

People wept, argued, understood, stood longer than they expected, and left changed.

A reporter asked Richardson what the photograph meant.

She said what the image had told her the first night she saw it: Sarah refused to be erased.

She left proof.

A hand signal in lace became a ninety-word indictment of a system that buries women twice—once in the ground, once in the files.

The story moved from local coverage to regional outlets to national platforms.

Social media amplified it in ways museums cannot, connecting an encoded hand to current conversations about violence against Black women, under-investigated cases, and a legal system still failing victims far too often.

And then a descendant reached across time with the kind of email historians keep forever.

The subject line did not try to be poetic.

The body did the work.

A woman in Chicago had a family photo dated around 1900 showing a man in a well-cut suit with a card tucked into his breast pocket.

On the card, faint handwriting read “Sarah.” The man was her great-grandfather.

He had left the South in the 1890s.

His name was Thomas Daniels.

The photograph is evidence of two truths: we carry love in small objects when institutions refuse to carry justice; and men who were told to run to save their lives sometimes honor the women they lost by keeping their names close to their hearts.

The Chicago image does not add new facts to the case.

It adds weight, and in public history weight matters.

What does this story teach beyond a single portrait? First, that emancipation did not end danger.

Postwar Charleston weaponized “respectability” to disguise harm.

Wealth insulated the white perpetrators of violence.

Black churches recorded what courthouses refused.

Benevolent societies did triage because triage was the only way to keep people alive.

Second, that embedded signals did not vanish when slavery ended.

Black women created ways to communicate distress in spaces where speech cost too much.

The continuity of coded safety practices offers a counter-history to narratives that suggest “freedom” arrived and made courage unnecessary.

Third, that money is not neutral.

The $200 advance in March 1895 may have been legitimate compensation.

It may also have been leverage dressed as kindness.

Power often transacts in sums designed to look like generosity while accomplishing removal.

Fourth, that photographs can function as both alibi and archive.

In a hostile legal system, portraiture proved property ownership, education, “character.” It was designed to be shown to a judge as visual argument: we are respectable; we would not break the law.

The code in a hand position changed the photograph’s job: it recorded a plea that could only be heard later.

The woman in the portrait treated the camera as a witness of last resort.

And fifth, that public history must balance specificity with care.

The Morrison family is not dragged into a modern trial that cannot be conducted across centuries.

Their role is presented with context, not exoneration.

The focus stays on the woman whose life the system erased and the community that wrote the truth in margins.

The exhibit’s long lines and quiet conversations produced the kind of outcomes institutions hope for but cannot guarantee.

Schools added units on reading historic photographs.

Museums developed guides for staff to recognize signals—hands, sightlines, objects, arrangements—and cross-reference with ledgers and church minutes.

Partnerships formed between archives and Black congregations where unofficial truth lived.

Descendants found names in their attics that mattered to how they understood themselves.

Some were the ones who helped, like a man in Seattle who traced his line to Thomas’s older brother and said the discovery rearranged the sense of what he could do with his life.

Some were the ones who were helped, like a woman in Toronto whose great-grandmother crossed into freedom in 1868 and spent fifty years helping others do the same.

The story does not offer justice in the classical sense.

It offers something else public history can deliver: naming, documenting, teaching.

Sarah’s hand pulled truth into the future.

Thomas’s card kept memory in a pocket.

Emanuel’s margin made doubt part of the record.

Columbia’s notebook wrote the word that mattered.

The Charleston History Center built an exhibit that taught people to see beyond the frame.

And a nation that still struggles to investigate violence against Black women found in a nineteenth-century portrait an answer to the question of whether women leave evidence when no one believes them.

They do.

In lace and geometry.

With fingers.

The closing has to return to the opening, because good stories keep their promises.

It was just a picture of a young couple in 1895—until someone looked closely at the woman’s hand.

The gesture—a small circle and three raised fingers—holds more than code.

It holds the courage to speak when speaking is not allowed.

It holds a community’s sorrow and strategy.

It holds a century of waiting for eyes trained enough to see.

And when those eyes finally arrive, the photograph changes jobs.

It stops being a family object and becomes a public record.

It instructs us to look for what is not posed, to listen for what margins say, to read the ledger entries people wrote when the law refused their cases, and to treat ordinary artifacts as the places where the extraordinary hides.

On the anniversary of the portrait, Richardson went back to the building where the studio once stood and watched the afternoon sunlight fall through tall windows onto tables where people drink coffee and plan their days.

She imagined April 1895—the couple arriving in their best clothes, the photographer adjusting backdrop and light, the woman lifting her fingers a fraction and setting them into the geometry of a code, the shutter opening and closing on something it cannot name.

She imagined August—the husband running to a house on Trade Street after a message says “fall,” seeing bruises that do not match a staircase, a doctor making a declaration that hides what he sees, a committee writing what it knows, a pastor adding a marginal note to give doubt one inch of recorded space, a man folding a card into his pocket and leaving a city that will not protect him.

She imagined October of a century later—people standing in front of glass cases and learning how to see what the boy in Chicago’s photograph learned to carry, and what a nation needs to learn to hear.

It was just a picture.

It became a witness.

That is what happens when the future chooses to listen.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load