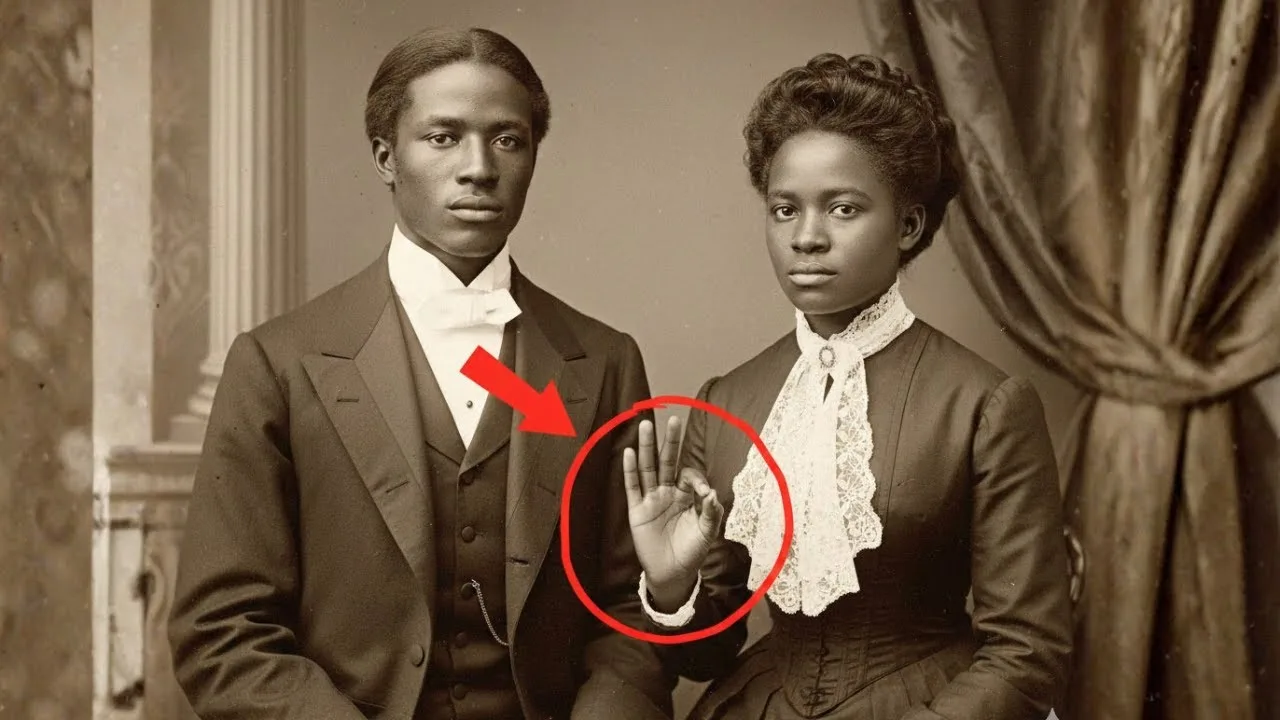

It looked like nothing more than a formal studio portrait: a young Black couple in Charleston, April 1895.

He in a too-large suit, posture rigid.

She in lace and high collar, expression carefully neutral.

Then a historian’s magnifying glass paused over the woman’s left hand, frozen in a deliberate configuration—the thumb and forefinger forming a small circle; the other three fingers slightly splayed, lifted.

What had seemed like etiquette revealed itself as signal.

A distress call preserved in silver nitrate and cardboard, waiting for someone to see it.

The question that followed wasn’t simply who they were—but what the hand was trying to say about danger, power, and how truth hides when the law prefers silence.

Below is a structured account of the investigation, the history, and the implications—step by step.

Context & Discovery

The story begins with a routine archival task and becomes a forensic read of a century-old emergency.

The Setting: Charleston History Center, An Ordinary Afternoon

Dr.

Maya Richardson, a historian specializing in Reconstruction-era Charleston, catalogs a donation of late 19th-century photographs.

Most are conventional: rigid postures, formal clothes, expressionless faces.

One card-mounted image labeled “Thomas and Sarah — Charleston, South Carolina, April 1895” catches her attention.

The Signal: A Hand That Isn’t Resting

The right hand hangs naturally; the left hand forms a subtle shape—thumb and index finger touching, three fingers raised apart.

Cross-references: the configuration appears in coded signals documented among Underground Railroad networks and mutual-aid societies as a discreet “help” marker.

Problem: The date is 1895—decades after emancipation.

Why use a clandestine distress sign in a formal portrait?

Immediate Hypothesis

The sign in the portrait is purposeful and urgent: an encoded plea embedded in a rare, expensive studio session, meant to survive beyond the moment and beyond the woman’s life.

Initial Research Trail

Maya pursues names, dates, and context to ground the photo in verifiable records.

Census and Vital Records

1900 census: Thomas (age 29), builder; Sarah (age 26), married in 1893, living on Trade Street.

Death record: “Sarah, wife of Thomas, died August 1895, age 26; cause—complications from injuries due to a fall.”

The timing: four months after the portrait.

Donation Provenance

The photographs came from a Trade Street house, cleared by an estate liquidation company.

Attic materials mostly discarded; one surviving box labeled “photographs, various” holds letters and bills.

Key find: a letter (Sept.

1895) from Mrs.

Catherine Simmons to Mrs.

Elizabeth Morrison mentions Sarah’s death and directs Thomas to contact Rev.

Patterson at Emanuel AME Church.

The Church Records

Where official records often obscure, church ledgers sometimes tell the truth in the margins.

Emanuel AME: The Ledger and the Note

Reverend Marcus Johnson locates marriage entry (April 7, 1893) and funeral entry (Aug.

28, 1895).

Crucial marginal note: “Inquiry from T.

Daniels regarding marks on deceased.

No answers provided.

Matter closed.”

Context from Rev.

Johnson: “Marks on deceased” often signaled suspected violence masked as accident.

Authorities rarely investigated Black deaths involving white households.

The Hand Signal’s Historical Use

Underground-era codes persisted in domestic service contexts.

Black women working in white homes had no legal protection; signaling became an informal safety mechanism within Black networks.

The Morrison Household

Understanding the employer’s ecosystem clarifies risk, opportunity, and motive.

Family Profile, Social Position, and Son’s Departure

James and Elizabeth Morrison: pre-war wealth from cotton trade; post-war status intact enough for servants.

Son Robert, 28, active in society pages, abruptly leaves for Europe in July 1895.

No further coverage; returns January 1896.

Departure suspiciously tracks to weeks before Sarah’s death.

Financial Records and a Payment

Courthouse deed files include a note: “Advanced payment to Thomas Daniels, builder—March 1895—$200.”

1895 dollars: substantial sum for a Black tradesman.

Possible interpretations:

Legitimate work order for household renovations.

Transaction designed to facilitate removing Sarah from domestic employment via marriage.

Covert hush mechanism aligning with reputational risk management.

The Benevolent Society Minutes

The internal record of Black mutual aid at Emanuel Church reveals the emergency calculus.

September 15, 1895 Entry

Thomas requests investigation, citing:

No prior illness for Sarah.

Fear and implied threats in her final weeks.

Observed bruises inconsistent with a fall; wrist marks; defensive wounds.

Committee decision:

Advises against pursuing formal complaint due to lethal risk of white retaliation.

Raises funeral funds; grants $45 to help Thomas start over in Columbia, South Carolina.

Urges immediate departure from Charleston.

Ethical Reality Check

The church protects the living—Thomas—from lynching and mob violence.

Structural injustice denies justice to Sarah; the system predicates safety on silence.

Columbia, South Carolina

The trail continues in a new city and another church ledger.

Beth-El AME Records

Pastor Ruth Williams produces Rev.

Thomas Nathaniel’s record book (1893–1905).

Entry (Oct.

1895): “Brother Daniels—arrived from Charleston—wife Sarah murdered by white family; death recorded as accident.”

Notes show community support, work assignments (pews, cabinetry), and pastoral counseling for trauma.

1898 entry: Thomas leaves for Chicago, early wave of northward migration.

The Man Who Grieved in Public

Thomas’s diary notes don’t survive, but pastoral summaries depict a grief that refuses self-forgiveness.

Pattern: men forced from communities after resisting injustice often rebuild by burying names publicly, honoring them privately.

Reconstructing the Likely Sequence

We can’t prove every detail—but the timeline narrows plausible explanations.

Timeline Highlights

1893: Thomas and Sarah marry.

March 1895: $200 payment to Thomas for work.

April 1895: formal portrait; Sarah’s encoded distress signal.

July 1895: Robert Morrison leaves Charleston for Europe.

August 1895: “fall”-related death; Thomas notes defensive injuries; inquiry denied.

September 1895: church advises relocation; grants support to leave.

1895–1898: Thomas rebuilds in Columbia; leaves for Chicago.

Reasoned Interpretation

Sarah’s distress signal anticipates danger in the Morrison house.

Robert’s departure may reflect emerging scandal or preemptive avoidance.

The “fall” narrative conceals violent death; injuries suggest struggle.

Black institutions shield the living in a system designed to destroy those who demand accountability.

The Photograph Becomes Exhibit

Research must live where people can see and feel, not only in journals.

Academic Publication

Title: “Hidden in Plain Sight: Sarah Daniels and the Silent Testimony of the 1895 Charleston Photograph.”

Documentation includes high-resolution image, church minutes, probate records, census entries, and timeline logic.

Public History Installation

Exhibit: “Unspoken Truths—Hidden Messages in Historic Photographs.”

Centerpiece: the portrait, with interpretive panels explaining the hand signal, the investigation, and violence against Black women in the 1890s.

Response: crowded opening, audience comprehension deepens as viewers notice Sarah’s hand, then read the margins of history.

Analysis: What This Case Reveals

Beyond one portrait, a map of how power hides violence and how communities record truth.

Violence by Disguise

“Accident” becomes legal euphemism; bruises become “unfortunate falls.”

Medical gatekeepers often served household reputations over victims.

Codes and Networks

The hand signal: an artifact of clandestine safety protocols.

Black churches: archives of unofficial truth; benevolent societies as crisis responders.

Money, Mobility, and Control

Payments can mask coercion or buy silence.

Abrupt departures (Europe 1895) indicate reputational triage.

Relocation grants (“go north”) reflect pragmatic risk calculus.

Gendered Injustice

Black women working in white homes faced sexual violence without redress.

“Marks on deceased” notes in church ledgers substitute for investigations denied by law.

Ethical Reckonings

The questions this story asks cannot be shrugged off with “we’ll never know.”

If the hand signal was a plea, who was meant to understand it—future viewers, or contemporaries in Black networks?

Does publishing the story now honor Sarah’s intent, or expose family names to belated scrutiny? Public history’s duty leans toward truth telling with rigor and care.

Was the church “cowardly” to advise Thomas to leave? In the calculus of 1895, saving a life required surrendering justice.

That is the indictment of the system, not of the church.

How should we treat the Morrison records? Contextualization prevents simplistic villainization while refusing neutrality about harm.

Implications for Public Memory

What to do when a portrait speaks louder than the caption.

Museums must train staff to recognize signals—hands, objects, arrangements—that encode messages.

Digitization projects should add annotations for likely clandestine signs.

Community partnerships with churches and Black historical societies are critical; official records understate truth.

Educators can use this case to connect past and present: violence against Black women remains under-investigated; signals still travel in coded forms today.

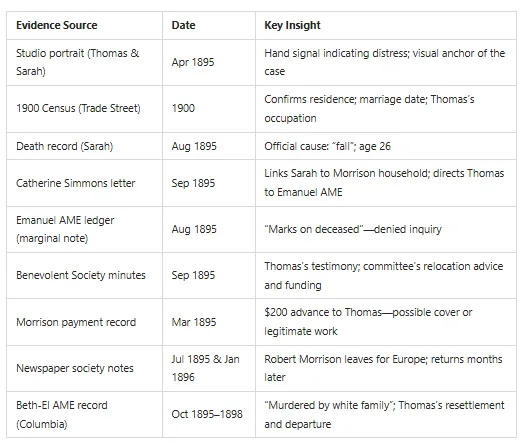

A Table of Key Evidence

Below is a concise summary of pivotal sources and what each contributes.

Summary: Together, these sources create a coherent narrative of signal, violence, concealment, and survival logistics.

Closure, If Not Justice

Maya’s article and exhibit do not prosecute.

They do something else essential: they name, document, and teach.

The portrait’s hand has done its work: it summoned a researcher across time.

The church’s margins spoke the truth when the courthouse would not.

The museum carries the story into classrooms and living rooms, inviting readers to look again at images they thought they understood.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load