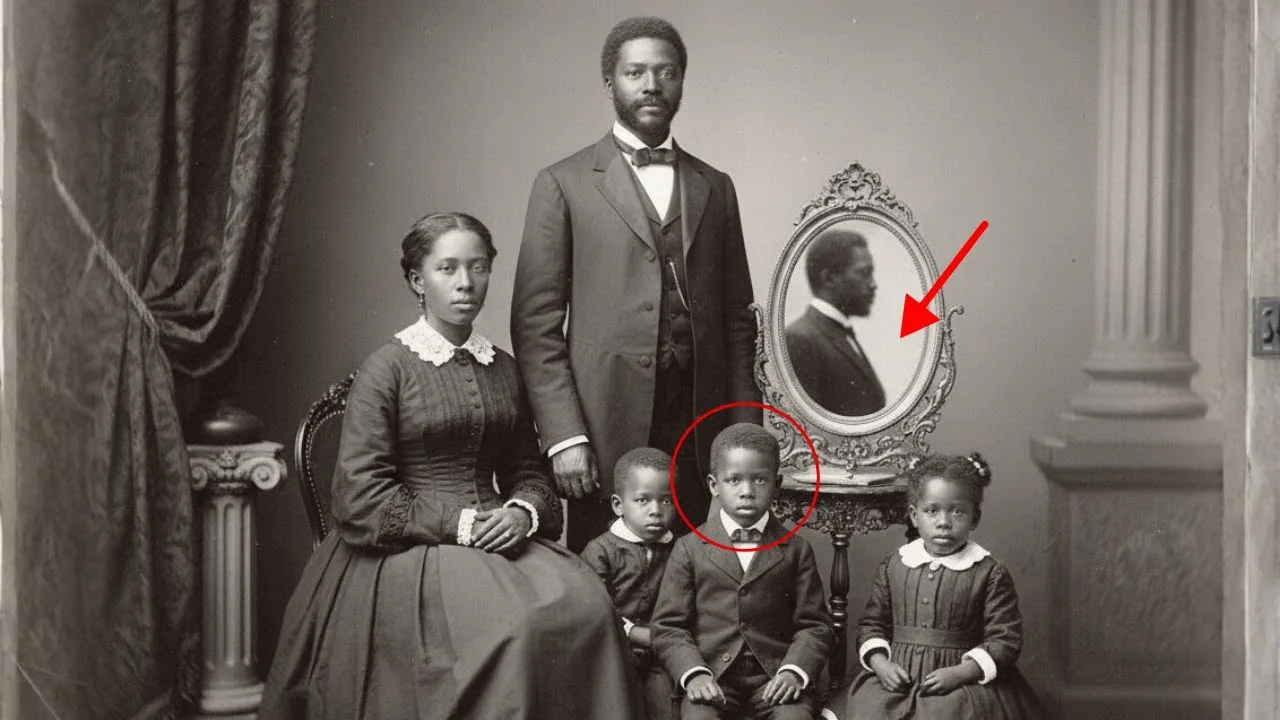

It looked like an ordinary family photograph from 1868—five well-dressed figures arranged the way studios arranged people when time itself had to hold still for the camera.

In the image, a Black father stands in a dark suit with a hand resting over his wife’s shoulder.

She wears lace and quiet resolve.

Two older children stare into the lens with the fixed seriousness that age and the era demanded.

And then there’s the youngest boy, perhaps six, who isn’t looking at the camera at all.

His eyes are turned right—away from the staged backdrop and toward something outside the frame.

Nothing else about the photograph tried to say more than it had to.

But his gaze wouldn’t stay in place, and a sliver of mirror behind a drape caught enough light to turn suspicion into a story.

The picture arrived at the Philadelphia Historical Society tucked inside a worn leather folder, part of a bundle an elderly woman donated while cleaning her grandmother’s attic.

Dr.

Sarah Mitchell, a historian focused on Black life after the Civil War, had sorted hundreds of similar portraits and expected this one to be just another entry in a long ledger of faces and names.

She almost slipped it back into its sleeve before the unusual detail stopped her—a child’s gaze that did not conform.

Early portrait makers trained families to keep still, look forward, honor the expense of a sitting by following instructions.

A turned gaze in an 1868 studio setting was either a mistake—or a message.

She adjusted a desk lamp and the magnifying glass did the rest: along the edge of a drape, a thin reflective surface glinted.

In 19th-century studios, mirrors were tools for light.

In this photograph, that sliver of silvered glass captured a blurred human shape just outside the field of view—a figure who should not be there.

The boy wasn’t daydreaming.

He was looking.

The donor’s card listed a phone number.

When Mitchell called, Dorothy Peterson answered and matter-of-factly identified the subjects: Thomas and Martha Williams; their children, Thomas Jr., Clara, and Samuel, the littlest boy.

Then Dorothy shared one line she never forgot.

“He told me that photograph was taken on the most dangerous day of his life,” she said, speaking of Samuel, her great-grandfather.

“He said it proved his family were heroes, even if no one could ever find out.” She’d written it off as memory playing tricks—until the historian’s questions made the old words sharp again.

The basic record trail aligned quickly.

City directories listed Thomas Williams as a blacksmith on South Street; Martha as a seamstress.

They owned their home, a rarity then for a Black family.

School records showed the older children enrolled at the Institute for Colored Youth, one of the few avenues to quality education for Black Philadelphians.

Then a small newspaper item from July 1868 bent the light differently.

Authorities had “investigated a local negro family in a suspected harboring case,” the clipping read with the condescension of the time.

No charges were filed.

The family denied wrongdoing.

The matter was “closed.” On paper, emancipation had arrived three years earlier.

In practice, pockets of illicit bondage persisted across the South, and the clandestine routes that had ferried people to freedom before the war had not vanished just because a statute said so.

They adapted, grew quieter, shifted north to safe houses and back rooms, and funneled as many as they could toward Canada, where United States law had less reach and fewer allies.

Mitchell went to Race Street, where the studio imprint on the card mount—Wittmann & Sons—still marked the building, now a café with exposed brick.

Twenty dollars and polite curiosity opened a basement door.

Three wooden crates waited behind stacks of chairs: Wittmann archives, Handle with Care.

Inside lay glass plate negatives and business ledgers.

In a neat hand, entries named clients, dates, payments.

Most were ordinary.

Some were not.

July 23, 1868—Williams family—full portrait—$4.50—Special arrangement—Evening session.

Why shoot at night in an era that relied on daylight flooding through tall windows? There were only a few sensible reasons, and all of them involved privacy.

The notation appeared again and again across the late 1860s and early 1870s beside Black family names known to historians for quiet activism.

In the margins next to the Williams entry, a faint note: “RM—usual precautions.” Five pages later, in different handwriting: “RM departed successfully via back entrance.

Package secured.” The period’s code was blunt.

“Package” meant a person in transit—someone who would exit out the alley, enter a wagon with a false bottom, or slip on foot toward the next address in a chain of places that kept their names off official lists.

The studio was not just a studio.

It was a node.

Back at the society, Mitchell scanned the Williams portrait with a high-resolution rig, careful to enhance without inventing.

At four hundred percent, the reflection behind the drape hinted at a figure.

At eight hundred, shapes arranged into something human.

At twelve hundred, the silhouette of a young woman—perhaps mid-twenties—in a plain dress, hands held tight at her chest, stood off to the photographer’s side.

The angle placed her at the periphery of the scene, deliberately out of the main frame, in a space where a person could wait without being recorded—unless a mirror sliver happened to catch her.

The youngest boy’s eyes were locked in her direction, focused the way children focus when they’ve been asked to do something very important and very quiet.

The faintest suggestion at the corner of his mouth read not as mischief or boredom, but as participation.

In that instant, a six-year-old was on duty.

His family had staged an alibi—respectable portrait, home ownership, well-dressed children—to counter an accusation of harboring.

They had also, accidentally or on purpose, left proof behind: a reflection and a gaze.

Dorothy returned to the archive carrying a small cloth bag and a grief softened by time.

Mitchell laid the enhanced scan beside the original.

Dorothy covered her mouth.

“So she was there,” she whispered.

“He told me once about a woman in the attic for three days.

He said he took bread up when his mother nodded that it was safe.

He said she sang once, so quietly he had to lean in to hear.” Dorothy had always assumed it was before the war, period romance retold to a child.

The historian explained what the ledgers and clipping confirmed: the Underground Railroad didn’t end in 1865.

It adapted to a new legal reality in which rescuing a person from unlawful bondage was itself a crime to be hidden with greater care.

To the network’s participants, danger didn’t end when a proclamation was signed.

It changed shape.

The cloth bag held a leather journal written decades later by Samuel—the smallest boy in the portrait, grown into a man who lived to see the jazz age and wrote to anchor his children in the truth he feared would be forgotten.

His entries rarely grandstanded; they told of shop repairs, church suppers, weather, and small mercies.

But on a few pages he recorded the day that had branded itself on his memory.

August 12, 1923: “Fifty-five years since the photograph.

I was only six, yet I recall her face as I recall the faces of my own children.

Very afraid and very brave.

Mother told me later she had walked ninety miles, following stars and whispers.

I crept up with bread and water, soldier on a mission.

She called me her little protector.” November 3, 1931: “A historian came asking about the old days.

I told him what everyone tells historians, that brave work was done by brave people and many facts are lost.

I did not show him the picture.

I did not speak the name I later learned—Rachel Martin.

In 1889, she wrote from Toronto.

By then I had children.

Knowing she lived made me weep as I had not done since boyhood.

Mother saved the letter.” July 23, 1935: “Sixty-seven years today.

Mr.

Wittmann’s son died last year.

I went to his funeral and told no one that he had been as brave as any of us.

He opened his studio after dark, let families like ours pour respectability into the lens while someone slipped in behind a drape.

Did he know the mirror caught her? I like to think he did—to leave a witness for the future.”

Names matter for history to come out of the fog.

A ship manifest from late July 1868 listed a passenger “R.M.” sailing to Nova Scotia on a ticket paid by private charity.

Canadian records from the era are inconsistent, particularly for Black refugees who often altered or protected their names, but patience draws lines between dots.

A retired Toronto scholar emailed Mitchell: a Rachel Morrison appears in census rolls shortly after that ship’s arrival, “from Pennsylvania,” roughly the right age.

She married a carpenter in 1871, raised four children, volunteered for fifty years helping new arrivals find their footing, and died in 1921, buried in the Necropolis.

A small newspaper photograph showed a woman in later life framed by church members honoring her service.

The caption praised her work aiding families “adjusting to freedom.” If she changed her surname from Martin to Morrison for safety when she crossed the border, she followed a practice common to those who had been hunted across state lines by men who refused to accept defeat.

Her great-granddaughter in Toronto had a wooden box of papers and a single note pinned behind an old Bible page: “July 23, 1868.

The day I became free, thanks to the blacksmith’s family and the little boy who watched over me.” Across a century and a border, gratitude had kept its appointment.

The studio ledgers yielded more than a one-off.

Between 1866 and 1872, evening sessions recur—about twice a month—attached to Black families whose names recur elsewhere in abolitionist minutes and mutual-aid rosters.

The Patterson boarding house; the Hughes wagon maker whose vehicles were rumored to carry more than hay; the Morris household with church ties strong enough to trigger city suspicion twice.

Coded phrases repeat with grim utility: “Package secured.” “Departure confirmed.” “Safe arrival noted.” James Wittmann Jr.—who inherited the business from a father who, before the war, had made portraits for legal cases to humanize the enslaved—ran quiet logistics after dark in the postwar years.

A basement door opened to an alley that connected to service passages most Philadelphians never noticed.

From there, nights had their own choreography: a family arrived for a portrait with children in Sunday clothes; a back-door knock signaled that tonight was the night; a person waited, breathed, calmed heartbeats under a drape; the shutter clicked; the family thanked the photographer with too much gratitude for such a small transaction; the alley swallowed one more figure and returned silence in exchange.

The Philadelphia Historical Society’s exhibition did not sensationalize.

It refused to pry with modern certainty into places the past had kept private for good reason.

Instead, it set the original Williams portrait beside a carefully enhanced print, explained the limits of digital restoration, and walked visitors through how to read images with care.

Nearby hung sixteen other family portraits from Wittmann’s ledgers, each accompanied by the minimum facts needed to honor the risk taken and the roles played.

Samuel’s journal page—the one where he wrote, “She called me her little protector”—drew the longest line.

Dorothy stood beside the glass case and met Patricia Morrison Chen for the first time, two women bound by an act of courage older than their grandparents.

They had spent the morning trading stories, realizing that the language a six-year-old carried about bravery had met its twin on a slip of paper across an ocean of time: a woman remembering a boy who watched.

In the months that followed, the exhibition traveled and did what good public history does—it sent people to their attics.

Families on both sides of the border found names, letters, tintypes, and ledger entries that plugged into the same network.

A software engineer from Seattle traced his line back to Thomas Jr.

and said the discovery had rearranged how he measured himself.

An Ontario school district added a slim book about Rachel Morrison to its curriculum and called the unit “Ordinary Courage.” The café on Race Street kept hosting the exhibit’s evening talks; the barista told people how mirrors lie less than captions.

The museum posted a short guide—how to read for clues in 19th-century photographs without seeing what you want to see: watch hands, track sightlines, check backgrounds for reflective surfaces, compare studio ledgers to church minutes, read euphemism like a second language.

There were debates the exhibition could not avoid.

When names of white families appeared in city files attached to “investigations” of Black households, some visitors wanted modern reckoning applied to the long dead.

The curators framed context without flattening: the point wasn’t vengeance on ghosts; it was clarity about systems.

Hospitals had falsified causes of death to preserve reputations.

Police used “harboring” as a pretext to raid homes built on discipline and love.

Photographers like Wittmann took on risk in the currency they had—their business, their status, their freedom.

Benevolent societies at Black churches made pragmatic decisions: confront and risk a lynch mob or relocate and preserve a life for another fight.

The strategy wasn’t cowardice; it was math under duress.

The story’s power lay in showing how courage distributes itself—through a mother’s nod; a pastor’s ledger; a child’s steady eyes; a piece of glass that refused to forget.

On an anniversary of sorts—July 23—Mitchell stood on Race Street in evening light, held up her phone, and photographed the café window.

In the reflection, passersby walked past, unremarkable and irreplaceable.

She thought of the boy’s line: “most dangerous day of my life.” She thought of a woman who wrote that the day she became free owed itself to a blacksmith’s family and a small guardian who brought bread on creaking stairs.

She thought of a photographer who might have left a mirror where it would catch a secret not for the authorities, but for the future.

Earlier that day, a school group had clustered around the portrait.

A child, the same age as Samuel had been, had asked why the boy wasn’t looking at the camera.

“Because someone needed watching,” his teacher answered.

“And he knew how.”

The photograph holds still.

That is its job.

But within its stillness, movement remains—a lookout’s eyes, a figure in a mirror, a family standing a little taller than gravity suggests because they are holding up more than themselves.

For a century and a half, the picture waited for someone to notice what the youngest child noticed immediately: truth often lives just off-frame.

The camera did not intend to testify.

It did anyway.

And once the testimony is heard, the meaning of ordinary changes.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load