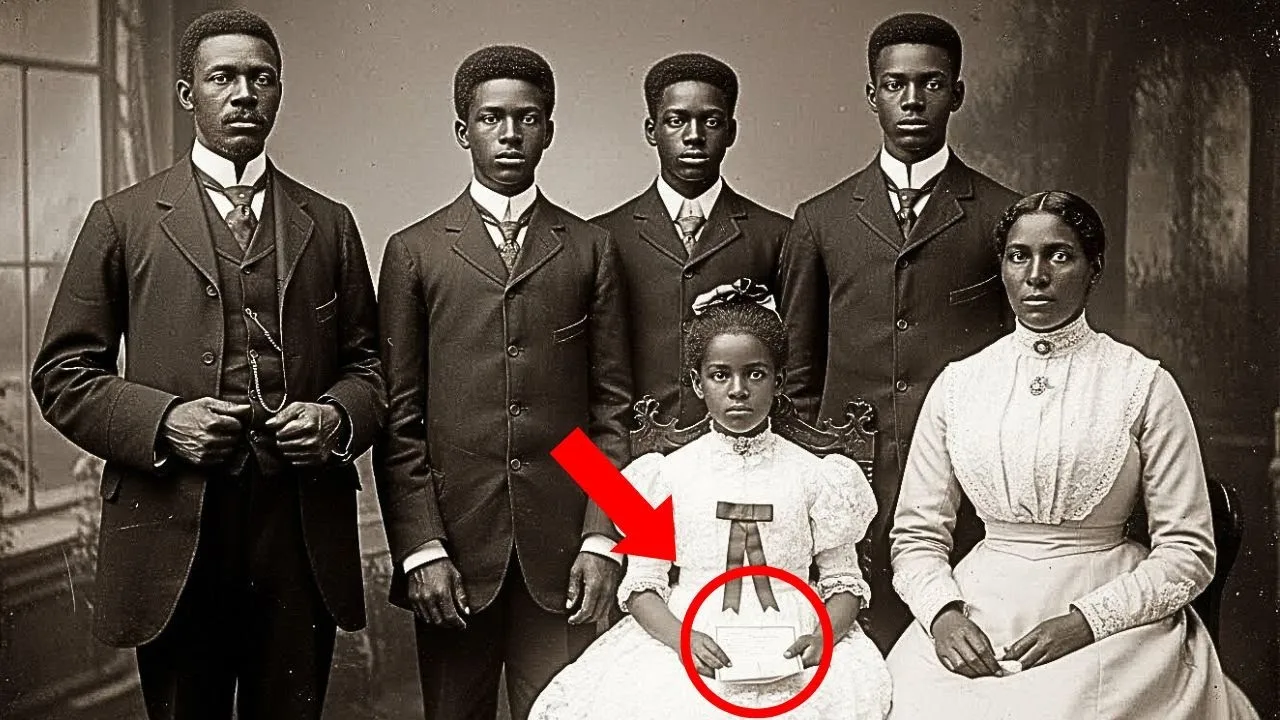

In a basement where history breathes through old cellulose and brittle paper, a single sepia portrait from 1892 rearranged everything a digital archivist thought she knew about how Black families fought to keep themselves intact in the post-Reconstruction South.

At first glance, it’s grace and dignity: a father’s steady hand, a mother’s composed gaze, three sons in dark suits, a little girl in white lace.

Then you zoom.

In her lap, carefully angled for the camera, the youngest daughter holds a folded document with an embossed seal—legal proof of identity and guardianship.

On the back, in faint pencil: “Carter family, Charleston.

May 1892.

Before departure.” It looked like a family keepsake.

It was evidence.

And it was protection.

Below is the complete narrative: the Carter family’s flight from Charleston, the custody battle they refused to lose, the investigator who chased them, the legal scaffolding that enabled the hunt, the photograph that became their shield, and the oral history that kept their truth alive.

—

The Photograph That Wouldn’t Behave

The basement of the Charleston Historical Society smelled like dust and memory—an aroma Maya Richardson had learned to trust.

She’d been a digital archivist for five years, teaching paper to talk with scanners and light.

On a September afternoon, she lifted a photograph out of a box labeled “Estate sale: Whitmore collection, 1890s.” Most images were routine—parades, civic leaders, formal gatherings.

One froze her.

Six figures in a studio portrait painted to resemble a parlor.

Not plantation grandeur.

Not staged opulence.

A Black family—impeccably dressed despite modest means—faces composed, spines straight, gaze direct.

The father stood left, hand resting on the oldest son’s shoulder.

The mother stood right, dignified in a high-neck dark dress.

Three teenage boys formed a row.

Center front, seated, a six-year-old girl in a white lace dress with dark ribbon and neat braids, hands folded over something small.

Maya scanned, zoomed, and adjusted contrast.

The object in the girl’s hands sharpened: the edge of a certificate, embossed seal catching light at a shallow angle.

Words resolved—“State of South…” and “Certificate of…” She flipped the photo.

On the back, in faded pencil: “Carter family, Charleston.

May 1892.

Before departure.”

The child’s complexion, even through sepia, was lighter than the rest—a detail that mattered.

In Charleston in 1892, a lighter-skinned Black child surrounded by a darker-skinned family, holding an official document, photographed “before departure,” signaled something more than sentiment.

This wasn’t just portraiture.

It was proof.

Proof of identity.

Proof of guardianship.

Proof against theft.

Maya made a list: Who were the Carters? Why the rush order? What was the document? Where did they go after the picture? She didn’t yet know that the next days would pull a century of buried conflict into the light.

—

Studio Ledgers and a Hidden Urgency

Archivists trust stamps.

This one said: Blackwell & Sons Photography, 127 King Street, established 1878.

When the studio closed in 1923, its business records were donated to the South Carolina Historical Society.

Maya requested three ledgers.

She opened the one marked 1892 and turned to May.

The entry was plain and explosive: “May 14, 1892 — Carter family portrait.

Six persons.

Payment in full (cash).

Rush order, completed same day.

Client: Samuel Carter, Negro Freedman, occupation tailor.

Note: family departing city.

Client requested extra prints.”

Three days later another entry: “May 17, 1892 — Visit from Marshall Whitmore inquiring about Carter family portrait.

Declined to provide information (client confidentiality).”

Within 72 hours of the portrait, an investigator asked for details.

The studio refused.

The ledger said “Marshall Whitmore.” Newspaper databases corrected Maya’s initial search to “Harrison Whitmore,” a private operative known for “retrieval services.” He had worked estate disputes, custody claims, and “missing persons” cases where the clients were white, the targets Black, and the stakes inheritance.

Whitmore had recently appeared in a 1891 court file for the estate of James Thornton, a deceased plantation owner with a sizable fortune.

Relatives claimed Thornton had fathered a child with an enslaved woman and wanted to block “illegitimate issue” from inheritance.

The case had been dismissed in March 1892—“insufficient evidence; missing parties.” Missing parties.

A mixed-race child.

An estate worth thousands.

The ledger’s urgency now had context.

—

Grace: Birth, Violence, and Adoption

Maya found the bridge in a physician’s letters donated by a descendant.

In January 1886, Dr.

Henry Polson wrote of a “distressing” birth at the Thornton estate: “The girl, barely 17, had been assaulted by Mr.

Thornton.

She survived delivery but died three days later.

The infant—female, fair complexion—was taken by Ruth Carter.

I provided documentation as requested by Mrs.

Carter.”

Ruth had been enslaved at the Thornton estate until 1865; she married Samuel Carter in 1867.

The baby—listed as “Grace” in vital records—entered the Carter home with Dr.

Polson’s papers recognizing Ruth and Samuel as guardians.

Thornton died the following week, never acknowledging the child.

In February 1891, “Thornton Family Trust vs.

Carter family” filed for custody and estate control, arguing “appropriate care and education” and implying “illegitimate issue” required management.

A judge issued a preliminary ruling in March 1892: temporary custody to the trust, pending a June hearing.

Grace was five.

The Carters knew what “custody” meant in practice—control of a child’s person and inheritance, often enforced by fear and institutionalization.

They did something brilliant.

Before leaving Charleston, they created evidence designed for court and for posterity: a family portrait where the youngest daughter held her birth certificate in frame—guardianship documented visually, love documented formally, an image that could be shown to church elders, train conductors, lawyers, and anyone who needed convincing that this child belonged with the people who had raised her.

Then they left.

—

Train Logs and Quiet Networks

Paper boards trains differently than tickets.

A railway conductor’s log from May 15, 1892, captured what a thousand faces forget: “Family of six Negroes paid cash for passage to Richmond.

Excessive luggage.

Appeared nervous.”

The Richmond line fed northward.

Philadelphia’s Bethleme Church ledger (May-August 1892) recorded “Family from Charleston: Samuel C.

Taylor (39), Ruth C.

Laundress (36), Thomas (16), James (14), William (12), and Grace (6).

Requested absolute confidentiality.

Provided housing.

Samuel employed at Taylor & Sons Tailoring.” A note two lines down: “Family reported being followed.

Moved to secondary location after two weeks.”

Networks matter.

The ledger shows an early version of today’s mutual aid: churches coordinating transport, housing, jobs, and discretion for families escaping legal and extralegal terror.

On June 10, 1892, Reverend Allen sent a letter of introduction forwarding the Carters to a church in Harlem.

Census records didn’t list “Carters.” That’s because they chose survival over continuity.

In Manhattan’s 1900 roll, Maya found “Samuel Porter,” tailor, “Ruth Porter,” laundress, and four children—Thomas, James, William, Grace.

Ages matched.

Occupations matched.

The Carters had become the Porters.

They had built a new life.

—

Grace Porter Speaks

When truth hides in decades, archivists defer to voices on tape.

The New York Urban League’s oral histories captured elders telling what papers didn’t.

One reel-to-reel file, digitized in 2003, held Grace Porter’s voice—steady, with a softened Charleston cadence.

“My name is Grace Porter, though that wasn’t always my name.

I was born in Charleston in 1886.

My mother died when I was three days old.

Ruth and Samuel Carter raised me.

They loved me.

They sacrificed everything so I could live free.”

She described men at the door claiming “family” like ownership, lawyers who looked at her “like property,” and a night train “where everyone stayed silent and alert.” Then came the photograph: “Papa Samuel took us to a photographer before we left.

He placed a paper in my hands and told me to hold it carefully.

‘This shows you belong to us,’ he said.

‘This shows you’re our daughter.

No one can take you away as long as we have this proof.’”

Grace moved through the years quietly—school in New York, teaching in Harlem, marriage, and confrontation.

In 1910, when a private investigator found her, she was an adult.

“I told him I wanted nothing from the Thornton estate.

I told him if he kept harassing my family, I’d go to the newspapers and tell everything—what James Thornton did to my mother; how his relatives tried to steal me.

He left and never returned.”

“I never wanted their blood money,” she said.

“Everything I valued came from Ruth and Samuel—my name, my education, my freedom.”

The tape ended with a sentence that belongs on walls: “I still have that photograph from 1892.

It’s not just a picture.

It’s proof that love is stronger than law.”

—

Descendants and an Heirloom

A genealogy forum led Maya to Jasmine Williams, Grace’s great-granddaughter, a high school history teacher in Brooklyn.

They met in Fort Greene.

Jasmine brought a leather portfolio holding the family’s copy of the 1892 photograph—identical pose, identical faces, identical document in a child’s lap.

The Carter image had traveled through boxes and banks and memory.

Jasmine also carried Grace’s birth certificate in a sleeve—Dr.

Polson’s signature intact.

“My grandmother told me this was the most important thing in our family,” Jasmine said.

“It represented everything we came from.” Grace had protected her children from the worst specifics, preferring to exalt Ruth and Samuel—“Mama Ruth” and “Papa Samuel.” Their sons carved lives: Thomas as a Pullman porter, James as a carpenter building Harlem homes, William running a barbershop until the 1970s.

Samuel died in 1919 “surrounded by family.” Ruth followed three years later.

At her funeral, Grace stood and said Ruth had saved her twice—once by taking her in, and once by loving her enough to risk everything.

Asked about the Thornton money, Jasmine shook her head.

“Grace said it was blood money.

She had dignity and freedom.

That was the inheritance she passed to us.”

—

The Thornton Estate: Greed, Lawyers, Dust

If love kept Grace’s family intact, greed dismantled the Thorntons.

Court dockets and newspaper files told a familiar story—money chasing myth until the money was gone.

The trust kept filing through 1893, pushing Charleston police to treat the Carters as fugitives, hiring investigators to locate a child they called “illegitimate” when it suited their argument and “necessary” when it suited their greed.

By 1894, legal fees gutted the estate.

Without custody of Grace, portions of inheritance tied to direct descendants remained inaccessible.

Factions formed.

Accusations flew.

Property sold.

Foreclosure notices appeared.

A 1902 newspaper headline summarized the ruin with Southern tact: “The Thornton Curse: How a Cotton Fortune Crumbled.”

In 1894, Whitmore sued the trust for unpaid fees—the investigator had not found Grace; he had not been paid.

In 1908, the remaining assets were divided among relatives too bruised to claim victory.

One sealed affidavit waited in a drawer until Maya had it unsealed.

Dr.

Polson wrote it in 1910 as a safeguard: “I can no longer remain silent.

James Thornton systematically abused young women in his household.

The family’s pursuit of his illegitimate daughter is greed.

They seek to control her inheritance while denying her humanity.

The child was taken by Ruth Carter, a woman of integrity.

If the Thornton family continues harassment, I will testify publicly.”

The harassment stopped.

Paper can be cowardly.

This one made courage contagious.

—

From Basement to Gallery Wall

Six months after opening a box in a basement, Maya stood in the Charleston Historical Society’s main gallery as staff installed “The Carter Family: A Portrait of Courage, 1892–2024.” The centerpiece: a large-scale reproduction of the family photograph, flanked by the original she found and the treasured copy Jasmine loaned.

Under glass, a reproduction of Grace’s birth certificate.

On the walls: Dr.

Polson’s letters; studio ledger entries; church records; train logs; a timeline map tracing flight from South to North.

The exhibition included a section on custody conflicts affecting Black families then and now—how the presumption of property morphs into modern bureaucratic harm.

Jasmine helped curate it.

“Grace’s story didn’t end in 1892,” she said.

“It’s still happening.

Black families are still fighting to stay together.”

On opening day, visitors read, listened, and cried.

The most potent moment was easy to miss.

Jasmine arrived with her family.

Kennedy—eight, wearing white—stood before Grace’s image, eyes steady.

“That’s her,” Kennedy whispered, touching the protective glass.

“That’s my grandmother Grace.” Jasmine knelt, pointing at how the family stood slightly angled toward Grace.

“They kept her safe,” Kennedy said.

“Yes,” Jasmine answered.

“And we keep her story safe by telling it.”

Outside, cameras caught a descendant naming a victory.

“Grace Porter taught for 40 years, raised three children, lived to see the Civil Rights Act.

She never regretted not claiming the Thornton money.

She inherited something better—dignity, freedom, and love.”

—

Television, Interviews, and a Confrontation with History

A PBS documentary team asked Maya to participate in a film that would contextualize the Carters’ story without exploitation.

Historians traced patterns.

Dr.

Marcus Webb explained how white families pursued mixed-race children to control inheritance and signal social power.

“What the Carters did required enormous courage,” he said.

Dr.Sharon Mills dissected the politics of portraiture.

“These images weren’t just keepsakes.

They were declarations: ‘We are a family.

We exist with dignity.’ Including a birth certificate was brilliant—visual and legal documentation in one frame.”

Producers found descendants of the Carter sons.

They also located a Thornton descendant willing to speak.

Patricia Thornton Hayes, in her sixties, sat in front of a camera and confessed what many families lack the courage to say.

“I grew up with whispers about a lost fortune and scandal,” she said.

“No one told me the truth.

Learning what he did—and what my family tried to do to that child—is shameful.

They chose greed.

They destroyed everything.

Meanwhile, Grace Porter taught kids and built a life.

She won.

They lost.

That’s as it should be.”

The documentary followed Kennedy to King Street, near where Blackwell’s studio once stood.

She held a reproduction of the 1892 photograph.

“They were scared,” she said, “but they were brave.” At the historical society, she stood before the original image, long enough that producers stopped suggesting reactions.

“I’m thinking about how Grandmother Grace held that paper,” she said finally.

“It meant she belonged to people who loved her.

It meant she was safe.”

—

Letters, Lessons, and a Permanent Installation

The exhibition became permanent.

Maya spoke at a symposium about identity and resistance in the post-Reconstruction South.

Letters poured in—people who recognized their families in the Carters’ story, who used Maya’s methods to trace ancestors lost to custody battles and flight.

One woman in Georgia found her great-great-grandmother using church ledgers, train logs, and a single studio stamp.

“Your work showed me these stories matter,” she wrote.

“You helped me understand what my family survived.”

Jasmine delivered a keynote on translating historical trauma into action.

Kennedy, now eleven, sat on a youth panel explaining how she learned history.

“When I first saw the photograph, I thought it was cool—old and fancy,” she told the audience.

“Now I know it’s proof.

Proof my family always fought for each other, always survived.

When things are hard, I think of Grandmother Grace holding that paper.

It helps me be brave.”

Teachers brought middle schoolers.

One girl, about Grace’s age in the portrait, stood before the glass a long time.

“They really loved her,” she said finally.

“You can see it in how they’re standing close.” Her teacher asked her what the photograph says about families.

She answered without looking away: “Family isn’t just blood.

It’s who chooses to love you and protect you.

And sometimes being a family means being really brave.”

—

Why This Matters Beyond One Photo

– Photographs as protest: Black families in the late 19th century used studio portraits to assert dignity, belonging, and legal identity in a culture designed to deny all three.

The Carters’ inclusion of a birth certificate transformed a sentimental image into a legal artifact, ready to speak when courts refused to listen.

– Post-Reconstruction custody battles: White families pursued mixed-race children to control property and ensure social dominance.

Judges often sided with whiteness disguised as “proper care.” Flight wasn’t romantic.

It was survival.

– Mutual aid as infrastructure: Black churches and community networks moved families across state lines, found them work, and protected them from investigators—practical resistance within hostile systems.

– Oral history as corrective: Grace Porter’s recorded voice fills the spaces paper refuses.

When archives fail, elders tell the truth.

Digitization makes that truth durable.

– Descendants as editors of legacy: Jasmine and Kennedy demonstrate how families curate history without shame—centering love and courage, refusing to dignify perpetrators with attention they do not deserve.

—

Key Search Anchors for Researchers

– Blackwell & Sons Photography, 127 King Street, Charleston; studio ledgers (1892 entries)

– Charleston court records: Thornton Family Trust vs.

Carter family (1891–1892); preliminary custody ruling; case dismissal context

– Dr.

Henry Polson letters and 1910 affidavit; birth certificate (1886) naming Ruth and Samuel Carter as guardians

– Railway conductor log (May 15, 1892): family of six traveling to Richmond

– Bethleme Church ledger (Philadelphia, May–August 1892): Carter family aid and relocation note

– Harlem church records (June 1892): letters of introduction; settlement assistance

– 1900 Manhattan census: Porter household matching Carter family ages and occupations

– New York Urban League oral histories (1950s–1960s): Grace Porter interview

– Charleston Historical Society exhibition materials: The Carter Family—A Portrait of Courage (1892–2024)

—

A Clear Timeline

– January 1886: Grace born at Thornton estate; mother dies; Dr.

Polson documents guardianship to Ruth and Samuel Carter.

– 1886–1891: Grace raised behind Samuel’s tailoring shop in Charleston; family stability; growing estate dispute.

– February–March 1892: Thornton trust sues for custody; preliminary ruling grants temporary custody to trust; June hearing set.

– May 14, 1892: Carter family portrait (rush order); youngest child holds birth certificate; studio notes “departing city” and extra prints.

– May 15, 1892: Train to Richmond; conductor notes nervous family, cash payment.

– May 22, 1892: Philadelphia church ledger records Carter family; employment secured; confidentiality requested; relocation after two weeks due to “being followed.”

– June 10, 1892: Assisted move to Harlem; name change to Porter over subsequent years; census entry in 1900.

– 1893–1908: Thornton trust escalates and collapses; investigator sues for fees; estate dissolves; property sold.

– 1910: Investigator confronts Grace; Dr.

Polson files affidavit; harassment stops.

– 1919–1922: Samuel and Ruth die; Grace speaks at funeral; family stabilizes in Harlem.

– 1920s–1960s: Grace teaches in Harlem schools for forty years; raises three children; dies in 1964.

– 2003: Grace’s oral history digitized.

– 2024–2025: Photo discovered and exhibited; documentary produced; exhibition becomes permanent installation.

—

Interpretation Without Sensationalism

It’s tempting to write this like a thriller—night train, hard men, narrow escapes.

The truth is harder and quieter.

Legal systems enabled pursuit.

Churches enabled survival.

A photograph enabled proof.

The Carters did not leave for adventure.

They left to prevent harm.

That distinction matters.

So does the choice to center Ruth and Samuel rather than the Thornton fortune.

“Blood money” is not metaphor here.

The estate was built on enslaved labor and sustained by threats.

Grace and her family refused to anchor their lives to any of it.

This story sidesteps the easy arc—persecution, escape, triumph—by pausing at the photograph.

Samuel knew paper could be lost and testimony ignored.

He made an image that could travel, be duplicated, tucked into portfolios, placed under glass, and handed to children who need to understand that love can be documented when law denies it.

—

What the Photograph Still Does

Late one evening, with the gallery empty, Maya stood again before the image.

Six people, shoulder-to-shoulder, refusing to allow fear to twist their posture.

A father’s hand on a son’s shoulder; a mother’s chin lifted just enough to read as defiance.

Three boys making a row of quiet protection.

And a little girl holding proof that she belongs to people who will not be moved.

The photograph still does what it was made to do.

It asserts identity.

It reenacts guardianship.

It teaches strangers how to read hands and documents together.

It tells descendants who they are.

If you’re looking for a secret in the frame, avoid the impulse to search the background.

The truth is in the foreground—wrapped in lace, held by small fingers, angled just so.

It was just a peaceful family photo—until you saw what the youngest daughter was holding.

After that, it’s not just a picture.

It’s a promise.

And it keeps being kept.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load