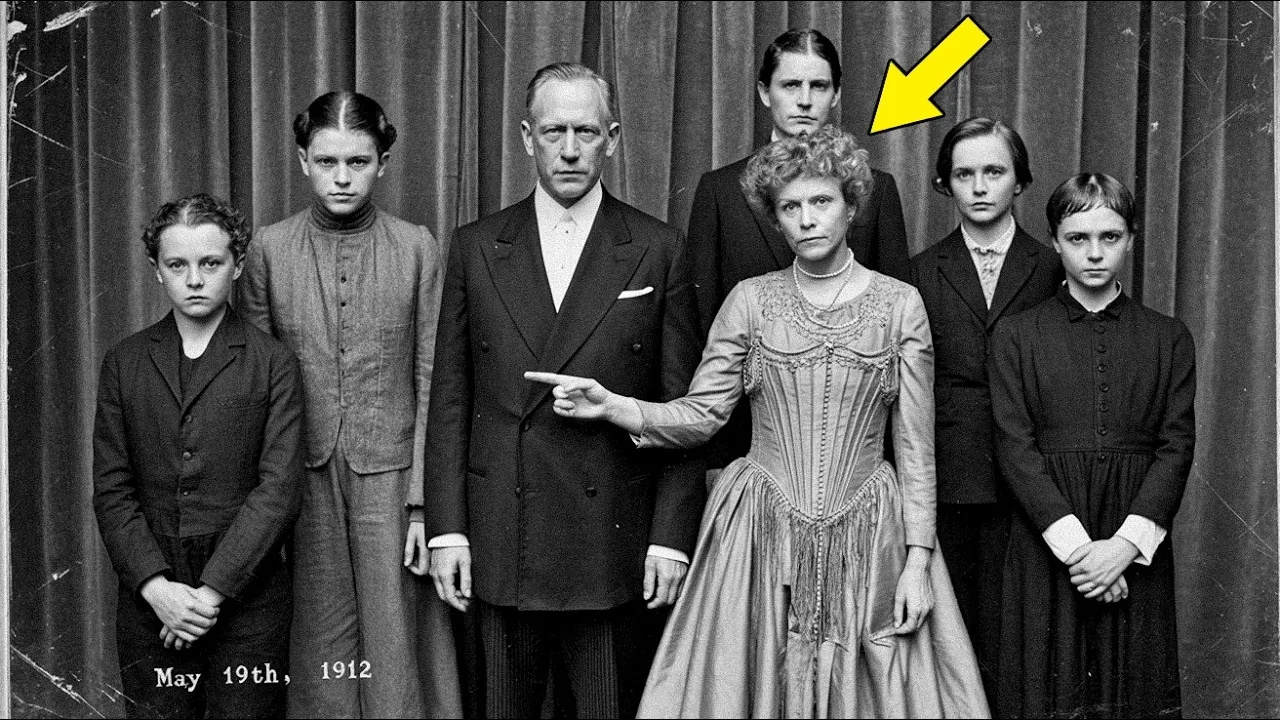

In 1912, a family posed for a photo — the mother’s strange gesture on the left hid a dark secret

Hello everyone and welcome to the channel.

Before we get started, if you’re already enjoying this type of content, leave a like to support me.

That helps the channel grow so much.

And if you want to follow stories like this one, don’t forget to subscribe and turn on notifications so you don’t miss our next videos.

Today, we’re going to explore a mystery that has remained hidden for more than a century.

Concealed within a simple family photograph taken in 1912, this seemingly ordinary image reveals something deeply disturbing when you look closely.

An unusual gesture, a detail that shouldn’t be there.

Discover with us what was really happening in that moment, frozen in time.

The photograph arrived almost by accident.

It wasn’t anything extraordinary at first glance, just a dusty glass plate discovered in a wooden trunk in an attic in Boston, Massachusetts.

The photographer who found it, a historical image restorer named Thomas Mitchell, was cataloging a collection of old negatives when his eye stopped on that specific frame.

The date was etched into the lower corner, May the 19th, 1912.

Thomas was 53 years old, a meticulous man with wire- rimmed glasses and the kind of attention to detail that had made him invaluable to museums and private collectors throughout New England.

He’d been working in the restoration business for nearly 30 years, and he’d seen thousands of photographs, portraits of stern-faced industrialists, proud families in their Sunday best, children in sailor suits staring solemnly into the camera.

Most followed predictable patterns.

Most told straightforward stories.

This family was wealthy or this family was respectable or this family wanted the world to know they existed.

But this photograph was different.

He first noticed it because of the quality of the negative itself.

Unlike many glass plates from that era which had degraded into a murky brown or clouded with age, this one was remarkably clear.

The detail was extraordinary.

Every fold of fabric visible, every strand of hair distinct, every subtle expression captured with crystalline precision.

It was the work of a master photographer, someone who understood light and chemistry and the human face with intimate knowledge.

Thomas carefully cleaned the glass plate, working with the precision of a surgeon.

He used distilled water and soft brushes, removing decades of dust and oxidation.

As the surface became clearer, the image emerged from the shadows like a photograph developing in a dark room.

It showed a family of seven people arranged formally in front of a studio backdrop.

The setting was elegant, expensive even.

Behind them, dark velvet curtains created a solemn atmosphere typical of the Edwwardian era.

When photographs were serious business, when people didn’t smile because the process took too long and smiling made your face ache, the men wore impeccable black suits with embroidered vests and gold watch chains draped across their chests.

The women were corseted into the fashionable silhouettes of the period, impossibly narrow waists, high collars, elaborate hats adorned with feathers and jewels.

Everyone wore rings.

Everyone wore jewelry that caught the photographers’s flash and gleamed with wealth.

This was clearly a family of means.

The patriarch stood in the center, a man in his 60s with a severe expression and piercing eyes.

His name, Thomas would later discover, was Edward Harrington.

He owned railways.

He made millions.

He knew senators and judges and ambassadors.

He was the kind of man who could walk into a room and have people shift aside to accommodate him.

Beside him stood a woman with careful, composed features.

Her name was Margaret Harrington, and she was Edward’s wife of 32 years.

She was in her early 50s, still handsome despite the fashion of the era that seemed designed to make women look as uncomfortable as possible.

Her hair was pinned in elaborate coils at top her head.

Her dress was an intricate construction of cream colored silk with lace overlays and pearl buttons.

Their five children ranged in age from 14 to 25.

Two sons, one with his father’s stern expression, one with softer features that suggested he might have inherited some of his mother’s temperament.

three daughters, all dressed in matching white gowns that marked them as unmarried, all with their hands positioned carefully to display wedding rings on their left hands.

Wait, no.

Thomas looked again.

Something was wrong.

The oldest daughter wore a ring.

So did the middle one, but the youngest had no ring, and her hands were positioned differently than her sisters.

Thomas pulled the photograph closer to his eye, but it was Margaret’s hands that stopped him cold.

Her right hand rested gracefully on the shoulder of one of her daughters, a pose of maternal affection, comfortable and natural, but her left hand, the one positioned on the other side of her body near her hip, was in a position that made Thomas’s stomach tighten.

Her fingers were extended in a way that wasn’t natural.

They weren’t relaxed.

They weren’t arranged the way a woman would naturally hold her hand during a 5-minute long photographic session.

The index and middle fingers were extended in a specific configuration, almost as if she were signaling something or pointing or trying to communicate a message.

Thomas sat back from his magnifying glass and stared at the print for a long moment.

It was deliberate.

It had to be.

No one would hold their hand in that position accidentally.

The photographer would have corrected it.

Photographers in that era were meticulous about these things.

They would position hands and faces and arrange the folds of fabric until everything was perfect, which meant Margaret Harrington had deliberately positioned her hand that way, and she’d held it there while the shutter opened and closed, preserving that gesture in silver and light for posterity.

Thomas spent the next week researching the Harrington family.

He pulled newspaper microfilm from archives.

He contacted historical societies.

He submitted inquiries to universities and private libraries.

He became obsessed with understanding who these people were and why Margaret Harrington would include such an unusual gesture in what was clearly meant to be an official family portrait.

The public records painted a straightforward picture.

Edward Harrington was a railroad magnate born in 1852 to a prominent New York family.

He’d inherited his father’s business interests and expanded them exponentially.

By 1912, he controlled several major railway lines that connected the Northeast to the Midwest.

He was worth millions, an astronomical sum for the era.

He was also, by all accounts, a respectable man.

He served on the boards of charitable organizations.

He’d been invited to diplomatic functions.

There were occasional mentions in society pages about gallas he’d attended, donations he’d made to hospitals and universities.

The kind of man whose name appeared in the right places associated with the right causes.

But the more Thomas dug, the more he found inconsistencies, gaps, missing pieces.

He found a newspaper article from the New York Tribune dated March 15th, 1912 that began to describe some kind of investigation into Harrington’s railway operations.

The article discussed concerns about working conditions for laborers and concerning reports from officials in Pennsylvania.

But the article was incomplete.

The rest of the page had been cut away, removed, lost to history.

Thomas found court records from 1911 that mentioned Harrington’s name in connection with some kind of legal proceeding, but the actual documents were missing from the courthouse archives.

The cler on the phone couldn’t explain why.

They simply weren’t there.

They’d been requested, the record showed, but never returned.

He found references in personal correspondents, letters between influential people that had been donated to historical societies that alluded to unfortunate business practices by certain industrial magnates, but the names weren’t explicitly stated.

The authors seemed to be speaking in coded language, avoiding direct accusation.

It was as if someone had deliberately removed large pieces of the historical record.

If you’re enjoying the video so far, please leave a like and subscribe to the channel.

It helps so much.

Leave your thoughts about the story in the comments below.

Thomas became convinced that the photograph held a key to understanding what had been hidden.

That unusual gesture by Margaret.

It was a message.

It had to be.

Why else would a woman of her status and education deliberately pose in such an unusual way for an official family portrait? He started digging into the archives, more specifically, looking for documents mentioning the Harrington family between March and May of 1912, the period between when Margaret had apparently become concerned about something and the date the photograph was taken.

And that’s when he found the letters.

They arrived at his office in a manila envelope forwarded by a librarian at Welssley College who’d heard about his research through an academic network.

The librarian had come across them while cataloging a donation from an estate sale.

Boxes of correspondence that had been found in an old house that was being demolished.

These particular letters had been addressed to Charlotte Witmore, Margaret Harrington’s younger sister who’d lived in Paris.

But the letters had never been sent.

They were still in their envelopes, sealed but never delivered, stored in a box with other personal effects that had apparently been kept for over a century.

Thomas opened the first one with trembling hands.

The paper was yellowed, fragile, threatening to crumble at the slightest rough handling.

The handwriting was elegant and precise, educated penmanship, the kind taught to young ladies of good families.

The date at the top was March 3rd, 1912.

My dearest Charlotte, it began, I hope this letter finds you well in Paris.

Life here in New York continues as it always has.

Endless social obligations, tedious dinners where the same people discuss the same inconsequential matters.

The weather has been unseasonably cold.

My roses have not yet bloomed.

But there is something happening in this house that terrifies me.

Something Edward is doing.

Something connected to his business dealings and other matters.

Things I cannot even write about clearly for fear that someone might read these words and use them against me.

I hardly know where to begin.

You know how Edward has always been ambitious, ruthless even in his business dealings.

Father warned me about it before we married, but I was young and foolish and thought love could soften such a nature.

It cannot.

Nothing softens it.

If anything, the years have only hardened him further, polished his ambition into something sharp and cold.

But this is different.

This is something else entirely.

Thomas kept reading, his heart pounding.

The letter continued for several pages, but large sections had been carefully razored away, deliberately destroyed by someone who wanted to erase specific details.

What remained were fragments, tantalizing glimpses of thoughts that had been partially erased, cannot leave the children alone with, “The authorities would never believe me.

Not against a man of his.

I found papers in his study, lists of names, addresses.

I don’t understand what they mean, but they filled me with dread.

He found me reading them.

His reaction was violent.

For one terrible moment, I thought he would strike me.

His hands were clenched.

His face turned a shade of red I’d never seen before.

He said, “If I ever again tried to interfere with his business interests, there would be consequences for the children.” And then in the margin in handwriting that was shakier, more desperate.

What does he mean by consequences? What is he capable of? Thomas set the letter down and rubbed his eyes.

His hands were shaking.

He opened the second letter.

It was dated March 17th, 1912.

Charlotte, I have discovered something.

Or rather, I have confirmed something I suspected.

Edward is involved in something criminal.

I don’t yet understand the full extent, but I am certain of this much.

There have been disappearances, children specifically.

I found a newspaper clipping in Edward’s study, poorly hidden beneath some business documents.

It was about a girl who went missing from the tenement district in Brooklyn.

Sarah Pollson, age 11.

The article was brief.

These things always are when the child is poor.

No follow-up, no real investigation, but the girl’s name was circled in Edward’s handwriting.

I searched further and found more clippings, more names, more children gone missing.

The articles are scattered across papers from January to the present.

Some from New York, some from Pennsylvania along the routes of Edward’s railway operations.

Charlotte, I believe my husband is involved in these disappearances.

The third letter, dated April 2nd, 1912, was the most explicit and the most heavily censored.

I have learned something terrible.

God forgive me.

I almost wish I hadn’t, but I must record it, even if only for my own sanity.

Even if these letters are never sent, I spoke with Bridget, our housemaid, the youngest one, only 17 years old.

She was crying in the servant’s kitchen.

I coaxed the story from her, though I’m not sure she wanted to tell me.

Two weeks ago, she was sent to Edward’s study to tidy up.

She was not supposed to be there.

Edward had given explicit orders that no one was to enter his study without his permission.

But the maid who normally performed that task had taken ill, and Bridget was assigned to substitute.

When she opened the door, she found Edward and a child, a young girl, perhaps 9 or 10 years old.

The child was here a long section had been razored away, leaving only tatters of paper and the ghost of handwriting underneath, bruises on her arms.

The girl was frightened.

When she saw Bridget, she tried to scream, but Edward put his hand over her mouth.

He didn’t see Bridget immediately.

He was occupied.

Bridget ran.

She didn’t know what to do.

She went to her room and waited for her shift to end.

When she came back the next morning, the girl was gone.

Bridget was called into Edward’s office.

He gave her money, a great deal of money, more than she makes in 6 months, and told her that if she ever mentioned what she had seen, she would be dismissed without references.

Without references, a young woman like Bridget has no future, no respectable work, only the streets.

She has been sick with fear ever since.

She only told me because she could no longer bear the burden alone.” Thomas set the letter down.

His throat felt dry.

He poured himself a glass of water with shaking hands.

He continued reading through the collection.

There were letters from late April describing Margaret’s growing certainty that something was profoundly wrong, combined with her growing desperation and helplessness.

She was trapped.

A woman in 1912 had almost no legal recourse against her husband.

She couldn’t divorce him without being ruined socially.

She couldn’t accuse him of crimes without proof.

And what proof did she have? The testimony of a frightened servant girl, newspaper clippings, her own suspicions and fears, and always beneath the surface of these letters was the question of what she could do to protect her children.

One letter dated May 5th, 1912 mentioned the photograph.

Edward has announced that we shall have a formal family portrait taken.

A prominent photographer is to be engaged, apparently one of the finest in the city.

Edward is very specific about the details.

He has instructed me on exactly how I am to position myself.

He has drawn diagrams.

Your left hand, he said to me, showing me a sketch should be positioned.

Thus, your fingers extended in this configuration.

Your face should be arranged like this.

This is important, Margaret.

This is a message.

Who the message? What message? To whom? I asked him to clarify and he became cold.

He said that if I asked questions, if I deviated from his instructions in any way, arrangements would be made regarding the children’s futures.

That exact phrase, arrangements would be made.

What does that mean, Charlotte? What is he threatening? I am trapped.

I cannot refuse.

His implication is clear.

I cannot deviate from his instructions.

Again, the threat regarding the children.

I am to pose for this photograph and make some kind of signal.

That is what it feels like.

That I am being forced to participate in some public communication that I don’t understand.

I am terrified.

And then in the final letter dated May 18th, 1912, the day before the photograph was taken.

Tomorrow we sit for the photograph.

I have barely slept in days.

My nerves are completely undone.

My hands shake.

I can barely eat.

I have decided something.

If I must participate in whatever this is, if I must make this signal that Edward demands, then I will also make a record of it.

I will document in these letters what is happening even if no one ever reads them.

Even if these letters remain hidden for decades, I will have told someone, even if only in words that may never be seen.

Tomorrow I will position my hand as Edward instructs.

Tomorrow I will smile for the camera as though nothing is wrong.

Tomorrow I will help him communicate whatever message he wishes to communicate.

And perhaps someday someone will look at that photograph and wonder.

Someone will notice that unusual positioning of my hand and ask questions.

Someone will search for the truth.

If that person is reading this, know that I am not mad.

Know that I am not hysterical or suffering from female complaints or any of the other dismissals that men use to silence women who speak inconvenient truths.

I am a rational woman who has observed criminal behavior and documented it and I am being silenced.

The letter ended there mid-sentence as if Margaret had been interrupted or had simply lost the ability to continue.

If that content is being useful, leave a like and subscribe to the channel to support me.

The envelope was dated May 18th, 1912.

It was never sent.

It had spent more than a century hidden away in a box, waiting to be discovered.

Thomas spent two sleepless nights reading through the entire collection of letters.

They painted a portrait of a woman in psychological distress.

Yes, but a woman whose distress seemed rooted in genuine observations rather than imagination.

Margaret had seen something or she had suspected something, and whatever it was, it had terrified her enough to cause her to attempt to document it, even knowing that her documentation might never be read.

The next morning, Thomas contacted the Boston Police Department.

He asked if there were any historical records related to Edward Harrington or investigations into his business dealings.

The officer he spoke with was professional but unhelpful.

The records from 1912, he explained, had been archived, and then, in an unfortunate incident in 1975, many of the oldest files had been damaged in a water leak in the basement of the archives.

“The specific files Thomas was asking about were among those lost.” “That’s interesting timing,” Thomas said carefully.

Lots of things get lost to history,” the officer replied in a tone that suggested he might understand there was more to the story than he was permitted to share.

Thomas then began cross-referencing the names Margaret had mentioned with historical records of missing children in the Northeast during 1912.

He pulled microfilm from newspaper archives.

He contacted historical societies in Pennsylvania.

He compiled a list.

Sarah Pollson, age 11, disappeared from Brooklyn, January 19th, 1912, never found.

James O’Brien, age 12, disappeared from Manhattan, February 3rd, 1912.

Never found.

Margaret Chen, age 9, disappeared from Boston, February 18th, 1912.

Never found.

Thomas, age unknown, described as dark-haired boy, approximately 8 years old, disappeared from the dockside area of New York, March 5th, 1912.

Never found.

A girl identified only as Lucy was reported missing by her aunt on March 22nd, 1912 from Newark, New Jersey.

Never found.

Seven children in total between January and May of 1912 had disappeared from cities and towns connected by Harrington’s railway lines.

Seven children from poor or workingclass families, the kind of children whose disappearances generated brief newspaper notices in minor publications, but sparked no major investigations.

But there they were in Margaret’s letters, documented as circled in Edward Harrington’s handwriting.

The pattern was undeniable.

The question was, what did it mean? On May 22nd, 1912, 3 days after the photograph was taken, Margaret Harrington was admitted to the Shady Oak Sanatorium for nervous ailments in Connecticut.

The admission records, which Thomas was eventually able to obtain after submitting formal requests and explaining his historical research, described her condition as acute hysteria with paranoid ideiation.

The attending physician, Dr.

Cornelius Winthrop, noted in his initial assessment, patient presents with severe agitation, delusion, and resistance to rational explanation.

She exhibits obsessive fixation on unsubstantiated claims regarding her husband’s alleged criminal activities.

When confronted with the logical inconsistencies in her narratives, specifically that a man of Mr.

Harrington’s social position would be incapable of engaging in such behaviors, the patient becomes increasingly distressed and defensive.

This resistance to reason suggests deep-seated psychological pathology, recommended treatment, prolonged rest, isolation, and medical intervention to calm the nervous system.

The sanatorium itself was one of dozens that had sprung up across the northeast in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

institutions devoted to treating the various nervous disorders that afflicted the wealthy and middle classes.

In theory, these were places of healing, quiet retreats where exhausted minds could recover their equilibrium.

In practice, many of them functioned more like prisons, particularly for women who had become inconvenient or troublesome to their families.

A woman who made accusations against her husband could be admitted to such an institution by her husband or her male relatives.

A woman whose behavior was deemed irrational or hysterical could be confined indefinitely.

The legal protections were minimal.

The medical oversight was peruncter.

And once a woman was labeled as mentally ill, her credibility was destroyed.

Margaret Harrington was confined to Shady Oaks for 2 years.

The treatment records, which Thomas obtained with difficulty and through formal legal requests, paint a picture of systematic deterioration rather than recovery.

In the first month, Margaret was reportedly resistant to treatment and belligerent towards staff.

She was placed in isolation and given regular doses of seditive medications, likely containing opiates or other powerful drugs.

By the second month, the notes describe her as calmer, though lethargic.

And by the third month, patient shows signs of compliance and reduced delusion.

What the clinical language was really describing, Thomas realized, was a woman being chemically subdued into silence.

Margaret was permitted few visitors.

Edward Harrington visited her twice during her 2-year stay.

According to the records, brief visits of less than an hour each.

His visits were documented in the simplest possible terms.

Husband visited patient calm discussed financial arrangements for continued treatment.

The other details were telling by their absence.

There was no mention of Edward Harrington advocating for his wife’s recovery or release.

No mention of him challenging the diagnosis or the treatment.

Only discussion of payment, only logistics.

Edward Harrington continued his life normally during these two years.

His business flourished.

He made significant profits from his railway operations.

His name appeared in the society pages, attending gallas and cultural events.

There were rumors documented in private correspondence that Thomas found of a possible government appointment that never quite materialized.

But there were also quieter rumors, the kind that appeared in letters between influential people, hints and suggestions about unfortunate labor practices in Harrington’s enterprises.

references to investigations that had somehow been quashed.

Mentions of children who had disappeared from work camps and railway construction sites, but nothing formal, nothing public, nothing that could be connected to Harrington with any legal certainty.

The children who had disappeared in 1912 were never found.

There were no bodies.

There were no arrests.

There were no trials.

After the initial brief newspaper notices, the cases seem to have simply been forgotten, lost in the shuffle of early 20th century urban life, where poor children disappeared regularly, and no one of consequence seemed to care.

Margaret was released from Shady Oaks in May of 1914, cured according to the attending physicians.

But those who saw her after her release described a woman fundamentally transformed.

She was quiet, subdued, eerily compliant, as though something essential had been removed from her during her confinement.

She never again spoke about her suspicions regarding her husband’s activities.

She never again wrote letters attempting to document her observations.

She maintained her public role as Edward Harrington’s wife, attending the required social functions, hosting the required dinner parties, performing the required duties of a society matron.

But those closest to her, her children, her few close friends, noted that she was no longer fully present.

She had retreated into some interior world from which she could not be reached.

Her daughter Elellanena in a personal diary kept for over 60 years and discovered after her death wrote, “Mother came home from the sanitarium different.

She smiled, but it was not her smile.

She spoke, but something was missing from her voice.

It was as though they had removed something while she was away, and what they returned to us was only a hollow imitation of the woman she had been.

I tried to reach her in the ways daughters do.

I asked her about her time away, hoping she would confide in me, hoping she would explain the mysterious illness that had required her confinement.

But she would not speak of it.

Her face would go blank and she would change the subject or excuse herself from the room.

I came to believe that whatever had happened to my mother at Shady Oaks had destroyed something in her that could never be repaired.

Margaret Harrington lived for another 21 years after her release from the sanatorium.

She died in 1935 at the age of 57.

Her death was attributed to sudden cardiac failure, a convenient diagnosis for a woman whose nervous condition had been so severe that she required commitment to an institution.

No autopsy was performed.

No investigation into the cause was conducted.

She was simply gone.

Edward Harrington lived for another 12 years after his wife’s death until 1947.

He died peacefully in his sleep at the age of 95, surrounded by his adult children and grandchildren.

He was eulogized as a great American businessman and philanthropist.

His obituary in the New York Times ran to several columns detailing his business accomplishments and charitable contributions.

There was no mention of any scandals, no mention of any investigations, no mention of any children who had disappeared.

History had recorded him as he wished to be remembered.

Successful, respectable, above reproach.

Thomas Mitchell’s work in reconstructing this narrative took nearly 2 years.

He traveled to multiple states, contacted dozens of historical societies and archives, submitted formal records requests under freedom of information laws, and conducted extensive interviews with descendants of the Harrington family who were willing to speak with him.

What emerged was a disturbing portrait of a man who may have committed serious crimes while remaining completely untouchable, protected by wealth, social position, and the systematic inability of society to investigate or prosecute men of his class.

But most importantly, what emerged was the question, what did the photograph mean? Thomas became convinced that Margaret’s letter was the key.

She had written that Edward wanted the photograph to serve as a message, but a message to whom and about what.

Some researchers who examined Thomas’s work suggested that the unusual positioning of Margaret’s hand might have been a signal, a code that would have been recognizable to others involved in whatever activities Edward Harrington was engaged in, a way of visibly marking Margaret as complicit or perhaps as a hostage to his good behavior.

Others suggested a more sinister interpretation that the photograph was a trophy, a document of power.

a way of forcing Margaret to participate in his crime by appearing in a public photograph that commemorated whatever acts he had committed or was planning to commit.

Still others theorized that it was simply a form of control, a way of demonstrating his absolute authority over his wife, his ability to force her to pose exactly as he commanded, to publicly perform his domination over her.

But perhaps the most haunting interpretation was offered by a psychologist who reviewed Thomas’s documentation.

That Edward Harrington was simply recording the fact of Margaret’s compliance.

That he was photographing his success in silencing her, in forcing her to smile while harboring terrible knowledge, in making her complicit in his concealment of crimes.

If you’re enjoying this video, a like and a subscription to the channel helps so much.

The children of Edward and Margaret Harrington went on to live respectable conventional lives.

The eldest son became a corporate lawyer.

He argued cases in federal court and never faced any scandal.

A daughter married a federal judge and became an important figure in Boston’s charitable circles.

Another son entered the diplomatic service and served as a consul in several European countries.

None of them ever publicly acknowledged or discussed any awareness of their father’s alleged activities.

None of them were ever investigated.

The family’s reputation remained intact, their wealth growing rather than diminishing over the decades.

Whatever Edward Harrington had done, whatever crimes he may have committed, whatever children he may have harmed, he had done so with impunity.

The systematic destruction of records that Thomas had documented throughout his research suggested that people of power had actively worked to conceal evidence of wrongdoing.

Documents had been removed from courthouse archives.

Newspaper articles had been torn from bound volumes.

Official files had been damaged in unfortunate accidents.

This was not a case of evidence being lost to the simple ravages of time.

This was evidence that had been deliberately hidden.

And at the center of it all was the photograph.

Margaret Harrington’s face frozen in a forced smile, her hand positioned in an unnatural configuration, her eyes haunted by knowledge of something terrible.

Thomas Mitchell published his research in a carefully documented academic article titled Hidden Messages: Photography, Silence, and the Concealment of Crime in the Gilded Age.

The article was published in a respected historical journal and received modest attention in academic circles, but many institutions were hesitant to draw the conclusions that Thomas seemed to be suggesting.

The Harrington family still had living descendants, some of whom retained significant wealth and influence.

To explicitly accuse Edward Harrington of criminal activity, even based on documentary evidence, was to invite legal challenges and social backlash.

The photograph was eventually donated to a regional museum in Massachusetts where it was hung in a small exhibit titled photographs and their stories interpreting images from the early 20th century.

A small placard beside it provided basic information.

Family portrait 1912 photographer unknown.

Subject: The Harrington family of New York.

But visitors to the exhibit would often stop and stare at the image for longer than they did at other photographs.

There was something about it that commanded attention, something unsettling, something that spoke to unease even for those who knew nothing of the history behind it.

Art historians and curators who visited the exhibit noted the same thing, that despite being a standard formal portrait, the image conveyed a sense of profound psychological disturbance.

The photographer had captured something beyond mere physical likeness.

He had captured tension, fear, secrets.

It’s as if you can see the lies in this photograph, one curator wrote in her notes.

You can see the strain of maintaining the facade of respectability while something dark fers beneath the surface.

Decades have passed since Thomas Mitchell began his research.

He is now retired, living quietly in a small house outside of Boston.

The Harrington family has largely faded from public consciousness.

Edward and Margaret are long dead, as are their children and many of their grandchildren.

But the photograph remains, and the questions remain unanswered.

What was Edward Harrington really doing during those years when children were disappearing from cities along his railway lines? Was he directly involved in their disappearances? Or was he aware of and protecting others who were? Was he engaged in human trafficking, in labor exploitation, in something even darker that we can only speculate about? Why did Margaret Harrington position her hand in that specific unnatural way? Was she trying to communicate something to someone? Was she making a signal that someone, perhaps law enforcement officials who had been made aware of Harrington’s activities, would recognize and understand? Or was she simply performing the gesture that her husband had commanded, a visual representation of his control over her? What happened to the seven children who disappeared in 1912? Were they trafficked through Harrington’s railway networks to other cities? Were they employed as child laborers in dangerous conditions? Or did something even worse happen to them? Why was Margaret Harrington committed to the sanatorium so quickly after the photograph was taken? Was Edward responding to perceived threats? Did he fear that Margaret might go to the authorities? Did he need to silence her before she could speak? Or did her commitment happen for reasons that have nothing to do with her accusations? And her letters are simply the ravings of a disturbed mind.

These are questions that cannot be definitively answered.

The documentary evidence is fragmentaryary.

The people who knew the truth are dead.

The records have been destroyed or hidden away.

And perhaps that is the most disturbing aspect of this story.

Not the specific crimes that may or may not have occurred, but the system that allowed them to remain hidden.

The social, legal, and institutional structures that protected powerful men from accountability, that silenced women who spoke inconvenient truths by labeling them mentally ill, that allowed the disappearances of poor children to go uninvestigated.

This was not a remote historical anomaly.

This was not a unique aberration in an otherwise just system.

This was how the system worked.

This was how power operated in 1912.

And in many ways, these patterns persist today.

The photograph represents that system made visible.

It captures the moment when a woman is forced to participate in her own silencing.

When she’s compelled to smile while harboring terrible knowledge, when she is made complicit in the concealment of crimes through her own image.

Margaret Harrington’s letters represent an act of resistance, an attempt to leave a record, even if it might never be read, even if no one might ever believe her.

She documented what she had seen and what she suspected, knowing that she might be committed to an institution for doing so, knowing that her credibility would be destroyed, knowing that she might be permanently silenced.

And in a sense, she was.

Her voice was taken from her for 2 years in the sanatorium.

She spent the remaining 21 years of her life in a state of chemically induced compliance.

She never again attempted to document her observations or seek help.

But her letters survived, hidden in a box for over a century.

They eventually emerged into the light.

And even if they cannot prove specific crimes, even if they cannot definitively answer the questions that surround the Harrington family, they serve as a testament to a woman who tried to bear witness to something terrible.

The photograph of the Harrington family is displayed in a climate controlled room in a regional museum in Massachusetts.

Occasionally, researchers and historians and curious members of the public come to view it.

They look at Edward’s stern face.

They look at Margaret’s forced smile.

They look at the children arranged formally behind their parents and they wonder.

They wonder what that unusual gesture means.

They wonder what happened to the people in the photograph after it was taken.

They wonder if anyone ever received whatever message Margaret was attempting to send through that deliberately positioned hand.

Most of all, they wonder about Margaret herself, about what she knew, about what she tried to communicate, about what was taken from her when she was committed to the sanatorium, and about the decades she spent in silent compliance after her release.

The photograph is a frozen moment, but it is a moment that opens onto an abyss.

Because once you know the history, once you know about Margaret’s letters and the missing children and the destroyed records, you cannot look at that image the same way again.

It becomes not just a portrait of a family, but a portrait of a system.

A system that protected the powerful while silencing the vulnerable.

A system that allowed crimes to go unpunished and then hid the evidence of those crimes.

A system that labeled women as hysterical when they tried to speak truth to power.

And it becomes a question that echoes across the decades.

What did Margaret know? What was Edward doing? Where did those seven children go? The answers may be lost to history, but the questions remain, preserved in glass and light, frozen forever in a photograph taken on May 19th, 1912.

And every person who looks at that image and feels that sense of unease, that intuitive understanding that something is profoundly wrong is in a way hearing Margaret Harrington’s voice across the century that separates us from her.

They are receiving the message that she tried so desperately to send.

The message that there was something terribly, awfully wrong and that she was powerless to stop it.

If you enjoyed this video, leave a comment below.

I love knowing your opinion and answering your questions.

If you’re not yet subscribed, take the opportunity to subscribe and turn on notifications so you don’t miss our next videos.

Thank you for watching and until the next mystery.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load