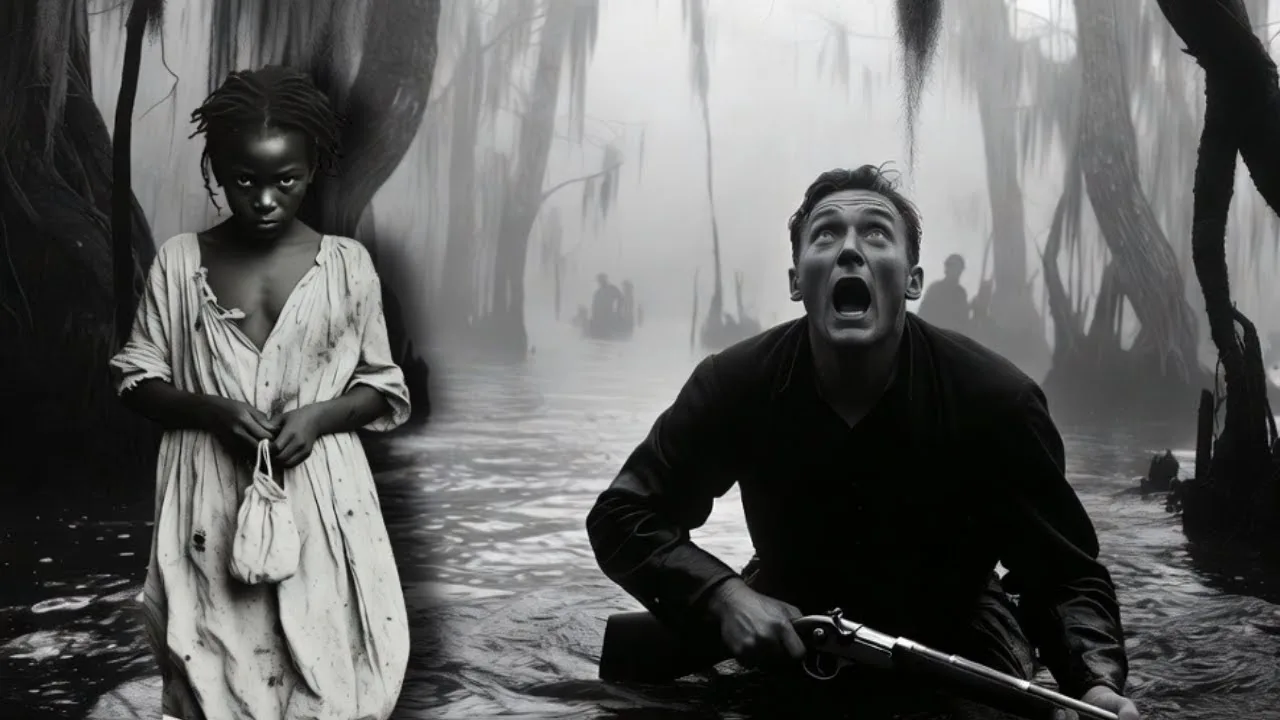

Born of Hoodoo in Florida — The Child Who Turned Slave Catchers to Shadows

The air in northern Florida hung thick with salt and silence, broken only by the rhythmic crash of waves against the barrier islands, and the distant calls of herands stalking through the marshes.

It was 1856, and the land between the St.

John’s River and the Atlantic coast existed in a peculiar state of tension, a borderland where the rigid architecture of plantation slavery pressed against something older, something that refused to be fully contained.

In the slave quarters of the Witmore plantation, among the weathered cabins that leaned like tired sentinels against the wind, a child was born who would become a whisper, then a legend, then a ghost story told to keep overseers awake at night.

If you’re drawn to stories of resistance that emerged from the darkest chapters of American history, hit that like button and subscribe to the channel.

Drop a comment telling us where in the world you’re watching from.

These stories belong to all of us and your presence here matters.

The midwife who delivered the child, a woman named Ru, whose hands carried the knowledge of three generations of healing, knew immediately that something was different.

The birth came during a new moon, when the darkness was absolute, and the only light came from a single candle that refused to stay lit.

Three times Ru had set flame to wick, and three times an unfelt wind had extinguished it, until finally she had worked by touch alone, her fingers reading the contractions like braille, guiding the infant into a world that had no proper place prepared for her.

When the child finally emerged, she didn’t cry.

She simply opened her eyes, eyes that seemed to hold flexcks of amber, even in that profound darkness, and stared at Ru with an intensity that made the old midwife’s breath catch in her throat.

The mother, whose name was Celia, had worked the Witmore field since she was 6 years old.

Her body bore the encyclopedia of slavery’s cruelties.

Scars from the overseer’s whip crisscrossed her back like a brutal map.

Her hands were calloused thick as leather from endless hours of labor under the merciless Florida sun, and her spirit had been worn down by a system designed to break human beings into tools.

She had been bred, that was the word the Witmores used, as if she were livestock to a man she barely knew, a field hand from a neighboring plantation who had been brought over for a single night and then returned.

His purpose fulfilled in the plantation’s grotesque arithmetic of human reproduction.

The transaction had been noted in the plantation ledger with the same clinical precision used to record the mating of horses.

Celia, age 22, bred to Caesar from Thornton property.

expected yield.

Spring 1856.

But when Celia held her daughter for the first time, something shifted in the architecture of her resignation.

The child’s skin was darker than her own, a deep brown that seemed to absorb and hold light rather than reflect it.

Her fingers, though tiny, gripped with surprising strength, and those eyes, Celia couldn’t stop staring into those eyes, which seemed to contain a wildness that the plantation had not yet learned how to tame.

In that moment, holding this strange and beautiful creature, Celia felt something she had thought the plantation had beaten out of her years ago.

Hope.

Not the desperate, clawing hope of survival, but something more dangerous.

The hope that this child might somehow escape the fate that had been predetermined for her before she’d even drawn breath.

They named her Zora after Celia’s grandmother, who had been born in Africa, and had carried to her grave stories of a land where black people owned themselves, where they built cities and forged iron, and answered to no master but their own conscience.

That grandmother had practiced what the plantation owners called witchcraft and what the enslaved community called hudoo, a system of folk magic, protection, and spiritual warfare that had traveled across the middle passage in the minds and hearts of people who had been stripped of everything else.

She had known how to read signs in nature, how to craft protections from roots and bones, how to call on ancestors and spirits to intervene in a world that seemed determined to crush her people beneath its heel.

She had been sold away when Celia was young, vanished into the vast machinery of the domestic slave trade, dragged south to the sugar plantations of Louisiana, where the mortality rate was so high that most enslaved people didn’t survive 5 years.

But her legacy remained in whispered techniques for healing, for hiding, for small acts of rebellion that the masters never quite understood.

Ru had known that grandmother.

She had learned at her feet, absorbing knowledge that was older than the American institution of slavery itself, traditions that reached back through centuries of African spiritual practice.

And now, looking at this strange child, who had come into the world under such peculiar circumstances, Ru recognized something she had seen only once before, in Celia’s grandmother in those final days before she was sold away.

It was a kind of power, a connection to forces that existed beyond the material world of cotton fields and auction blocks and ledgers, recording human beings as property.

From her earliest days, Zora was different.

While other children in the quarters learned quickly to make themselves small, to avoid the attention of white people, to move through the world with eyes downcast and voices muted, Zora seemed incapable of such diminishment.

She walked with her head up, her small shoulders squared, as if she carried some invisible armor that protected her from the weight of subjugation that crushed everyone around her.

She looked white people directly in the eye, a transgression that could, and often did, result in brutal punishment.

At 2 years old, she wandered away from the quarters and was found in the main house, sitting in the parlor, touching the piano keys with a curiosity that seemed to mystify even her mother.

The sound that emerged was not the random noise of a child’s exploration, but something that almost resembled melody, as if her fingers knew where to fall without being taught.

The overseer, a man named Garrett, whose cruelty was legendary even among overseers, wanted to whip her then and there.

He was a tall man with a face weathered by years of Florida’s sun, and eyes that held no warmth, no mercy, no recognition of the humanity of the people he was paid to brutalize.

Got to break that spirit early.

he’d said, reaching for his coiled leather whip.

The one he kept oiled and ready, the one that had opened the skin of dozens of backs, the one he seemed to take pleasure in wielding.

“Let this one think she’s special, and she’ll be trouble her whole life.

Better to teach her now what she is.” But something stopped him.

Later, he would tell the other white men that he’d felt a sudden pain in his chest, sharp and constricting, like an iron band tightening around his ribs until he couldn’t draw breath.

His vision had blurred.

His legs had gone weak, and for a moment he’d been certain he was dying.

The sensation had been so intense that he dropped the whip and stumbled backward, gasping.

And then, the moment he’d stepped away from the child, the moment he turned his back on those strange, amber flecked eyes, the pain had vanished as suddenly as it had come, leaving only a dull ache and a profound unease.

He never touched Zora after that, though he made Celia’s life harder in retaliation, adding extra hours to her labor, reducing her rations, finding excuses to inflict punishment for imagined infractions.

He couldn’t articulate why he avoided the child, couldn’t explain the superstitious dread that filled him whenever she was near, but he learned to give her wide birth.

Celia knew they couldn’t stay.

The knowledge came to her gradually, building like storm clouds on the horizon, then all at once.

the certainty that this child would not survive the plantation’s particular form of slow murder.

Zora was 5 years old when Celia began to plan their escape in earnest.

And by then the girl’s strangeness had become the subject of constant whispered conversation in both the slave quarters and the main house.

The enslaved community spoke of her with a mixture of reverence and fear.

Seeing in her something that might protect them or might bring down even harsher retribution, the white people spoke of her with unease, sensing something they couldn’t name, something that unsettled the natural order they believed was their birthright.

Strange things happened around Zora.

Dogs that had been trained to track runaways, vicious animals that could follow ascent across rivers and through swamps, would circle her and then sit, refusing their master’s commands, whining as if in pain.

White people who looked at her too long would develop sudden headaches that bloomed behind their eyes like thorns, forcing them to turn away.

The padlock on the smokehouse door had mysteriously opened when Zora stood near it one winter evening, allowing the enslaved community to take meat that would otherwise have been locked away.

A small theft that kept them from starving during the lean months when rations were cut.

Once an overseer’s horse, a normally dosile mayor, had thrown him when he’d raised his hand to strike Zora for some imagined infraction, rearing up with such violence that the man had been hurled from the saddle.

He’d broken his collarbone in the fall and had left the plantation shortly after, claiming the place was cursed.

Ru, who still lived in the quarters and had become something like a grandmother to the child, began to teach Zora deliberately what she had previously taught in fragments and secrets.

They would meet in the woods at dawn before the bell rang to summon the enslaved to the fields or in the deep of night when the moon was dark and the plantation slept.

Ru showed her how to read the signs, the way moss grew on trees to indicate direction, the patterns of stars that could guide travelers north toward freedom, the herbs that could heal or harm depending on preparation and intent.

She taught her the old words, the prayers that were not quite prayers drawn from traditions that predated the Christian religion the masters tried to force upon them.

She taught her the ways of asking the spirits for protection and guidance of creating charms and mojo that could shield against evil or bring misfortune to enemies.

And she taught her something more dangerous, something that could get them both killed if discovered.

She taught her that she was not property, that the world the plantation owners had built was not natural or inevitable, but constructed by human hands, and therefore able to be destroyed by human hands.

She taught her that the chains were real but not eternal, that the system of slavery was vast but not invincible, that every empire built on blood and suffering eventually crumbled into dust.

These lessons were radical in a world designed to convince enslaved people of their own powerlessness, and Ru delivered them with the gravity of someone passing on sacred knowledge.

Zora absorbed everything with a hunger that sometimes frightened even Ru.

The child seemed to understand instinctively what others had to be taught laboriously.

She could identify plants by touch in complete darkness.

She could sense when danger was approaching before it arrived.

She dreamed of things that later came to pass.

the overseer’s broken bone, a fire in the cotton barn, a white man’s sudden illness.

The other children avoided her, unnerved by her intensity.

By the way, she seemed to exist partially in some other world they couldn’t perceive.

The years passed with the grinding slowness that characterized life on the plantation.

Each day was like the one before it.

The same brutal labor, the same insufficient food, the same casual violence, the same systematic degradation designed to reduce human beings to beasts of burden.

But beneath the surface monotony, things were changing.

Zora was growing, and with her growth came a deepening of her powers, a strengthening of whatever strange connection she had to forces beyond the material world.

The catalyst came in the autumn of 1861.

The Civil War had begun that spring with the bombardment of Fort Sumpter, and the plantation’s white men were leaving to fight for the Confederacy’s right to keep human beings in chains.

Young Witmore, the master’s eldest son, had written off in his new gray uniform, speaking grandly of honor and heritage, of defending the southern way of life against northern aggression.

The master himself was too old to fight, but he’d sent three of his four sons, keeping only the youngest to help manage the property.

With fewer overseers and more chaos, with the structure of authority weakened and distracted, the possibilities for escape had widened slightly.

But the patrols had also intensified, and the punishment for attempted escape had become more savage as the plantation owners tried to maintain control over a system that was beginning to crack at its foundations.

Just that summer, a man from a neighboring plantation had been caught trying to reach the Union lines that were advancing slowly through the region.

They’d brought his body back and hung it at the crossroads as a warning, letting it swing there for 3 days until the smell became unbearable, and even the white people couldn’t stand to pass by.

The enslaved community had been forced to watch, to witness what happened to those who dared to run, to absorb the lesson that freedom was not worth the cost.

But the lesson some of them learned was different from the one intended.

Some of them looked at that body and felt not fear but rage, not submission, but determination.

Celia knew they had to go before Zora got older, before the plantation could begin to use her body in the ways it used all black women’s bodies.

The girl was 10 years old now, no longer a child, but not yet fully a woman, existing in that dangerous threshold where the plantation’s predatory attention would soon focus on her with full force.

Already Garrett had started looking at her in a way that made Celia’s stomach turn.

A calculating appraisal that she recognized because she had seen it before, had experienced what came after.

She had seen this story before, had lived parts of it herself in ways she could never speak about, and she would die before she let it happen to her daughter.

On a moonless night in October, when the darkness was absolute, and the autumn air carried the first hints of coming winter, Celia and Zora disappeared from the quarters.

They had been planning for months, but the final decision came suddenly, triggered by something Zora had seen in a dream.

She had woken three nights in a row with the same vision.

Men with dogs, chains, blood on the ground, and Garrett’s face twisted in triumph.

On the third night, she had gone to her mother and said simply, “We have to leave now.

If we wait, we won’t be able to go.” Celia had learned to trust her daughter’s instincts, these premonitions that seem to arrive like messages from some unseen realm.

And so she had nodded, her heart hammering with fear and desperate hope.

They took almost nothing.

A small sack of cornmeal that Celia had hoarded over weeks, hiding pinches of it each day in a rag she kept tied around her waist, a knife she had stolen from the kitchen and sharpened against a stone until its edge could split her hair, and a small cloth bag that Ru had pressed into Zora’s hands just before they left.

The old woman had gripped the child’s shoulders with surprising strength, her eyes bright with tears and something fiercer, a kind of ferocious pride.

“You got your grandmother’s gift,” she had whispered.

“Don’t let them make you forget what you are.

Don’t let them convince you that their world is the only world there is.” Inside that bag were roots pulled under specific moon phases, herbs dried and blessed with words in a language older than English, a few small bones from animals that had died natural deaths, a piece of high John the Conqueror root that Ru had guarded for decades, and a piece of paper covered in symbols that meant nothing to Celia, but that Zora seemed to understand instinctively.

When the girl had looked at those marks, crosses and circles and lines that intersected in patterns, her fingers had traced them as if reading, and she had nodded slowly, as if receiving instructions from the paper itself.

They slipped out of the quarters 2 hours after midnight, when even the most vigilant overseers had surrendered to sleep, and the patrol riders had passed on their circuit.

The night was warm for October, humid and heavy, and the darkness was so complete that Celia could barely see her own hand in front of her face.

But Zora moved through it with confidence, leading her mother by the hand, navigating by senses that Celia didn’t possess.

They headed east initially toward the river, moving in the opposite direction from where runaways typically fled.

Most escapees headed north immediately, trying to put as much distance as possible between themselves and the plantation, following the North Star towards some vague promise of freedom in Union Territory or Canada.

But Zora had insisted they go east first into the swamps and coastal marshlands that most people avoided.

“The water will hide us,” she had said.

And though Celia didn’t understand how a 10-year-old child could speak with such certainty about matters of escape and evasion, she followed.

They waded into the St.

John’s River as the first gray light of dawn began to thin the darkness.

The water cool and murky, reaching up to Celia’s waist and Zora’s chest.

The current was gentle here, and they moved with it, letting the river carry them downstream, while using their hands to push away from the banks, their feet only occasionally touching the soft mud of the river bottom.

They had been gone less than 6 hours when the alarm was raised.

Old Isaiah, who rang the bell that summoned the enslaved to their labor, had noticed immediately that Celia and Zora were missing from the morning count.

He had hesitated, his hand on the bell rope, wrestling with a decision that could mean the difference between life and death for the runaways.

Isaiah was nearly 70, too old to run himself, too worn down by decades of bondage to harbor much hope of freedom.

But he remembered Zora, remembered the strange things that happened around her.

And in that moment of hesitation, he made a choice.

He rang the bell at the usual time, as if nothing was wrong, and said nothing about the missing woman and child, until the overseer made his own count an hour later.

That single hour of delay would matter more than Isaiah could have known.

By the time Garrett discovered the absence and reported it to the master, by the time old Witmore’s face had purpleled with rage, and the decision was made to summon the slave catchers, Celia and Zora had put crucial distance between themselves and the plantation.

They had left the river and entered the coastal marshlands, a labyrinth of saw grass and standing water, of hammocks of solid ground surrounded by channels too deep to wade and too shallow to swim.

A landscape that seemed designed to swallow people and never give them back.

By dawn of that first day, the slave catchers had been summoned.

Leading the party was a man named Silus Krenshaw, whose reputation for brutality extended across three states and whose success rate in recovering runaway slaves was nearly perfect.

He was a professional hunter of human beings, a man who had made a fortune from the suffering of others.

And he approached his work with the cold efficiency of someone who had long ago stopped seeing his quarry as people.

He traveled with a pack of six trained blood hounds, animals bred and conditioned to track human scent across any terrain, and he brought with him three other white men who shared his profession and his complete absence of mercy.

Krenshaw was a tall man with a face like weathered granite, clean shaven in an era when most men wore beards, his jaw set in a permanent expression of grim determination.

He dressed practically in dark clothes that wouldn’t show dirt, wore boots made for long travel through difficult terrain, and carried a rifle across his saddle along with a coiled whip and a set of iron shackles that bore the stains of old blood and rust.

His eyes were pale gray, cold as winter sky, and they showed no more emotion when looking at a human being than when looking at a tree or a rock.

He had been doing this work for 20 years, since he was barely more than a boy himself, and he had developed it into a science.

When he arrived at the Whitmore plantation late that first morning, he listened to Garrett’s report with half his attention, while his eyes scanned the quarters, reading the landscape, calculating angles and distances.

“How long they’ve been gone?” he asked, his voice flat and professional.

Seven, maybe 8 hours, Garrett replied, his face flushed with anger and embarrassment.

Tail’s successful escape reflected poorly on an overseer.

Suggested weakness or negligence.

Krenshaw nodded, showing no reaction to this information.

8 hours was nothing.

He’d tracked runaways who had a 3-day head start.

The woman and a girl child, you said.

How old? Woman’s 27.

Girl is 10.

The girl slowing them down.

Then they won’t make good time.

Krenshaw dismounted and walked to the cabin where Celia and Zora had lived.

His dogs straining at their leashes, eager to work.

He entered the dim interior and spent several minutes examining the space, picking up a rag that still held Celia’s scent, a small corn husk doll that Zora had made, touching the pallets where they had slept.

His dogs clustered around these items, their noses working, absorbing the scent signatures that would become their obsession for the next hours or days or however long it took.

When he emerged, he seemed satisfied.

Which way they go? We don’t know yet.

Tracks suggest they headed toward the river, but then that’s where we start.

Crenaw swung back into his saddle with the ease of long practice.

We’ll have them before nightfall.

Woman and a child can’t outrun dogs can’t outrun horses.

It’s just a matter of time.

But as the hunting party set off toward the river, as the dogs picked up the scent trail and began to bathe with excitement, as Cshaw settled into the familiar rhythm of the chase, none of them knew what they were actually pursuing.

They thought they were hunting a desperate mother and her daughter, ordinary runaways driven by the common dream of freedom.

They didn’t know about Ru’s training, about the bag of roots and bones, about the dreams that came with warnings, about the strange things that happened around the girl with amber flecked eyes.

They didn’t know they were hunting Zora.

The dogs followed the trail to the river easily enough, their noses pressed to the ground, their muscular bodies quivering with purpose.

They reached the bank where Celia and Zora had entered the water, and there they circled, whining in confusion, trying to pick up the scent on the opposite bank or downstream.

Krenshaw watched them with narrowed eyes, reading their behavior.

Most runaways who used water to hide their scent traveled a short distance and then emerged on the opposite bank, trying to throw off pursuit.

But his dogs were finding nothing across the river.

They went downstream, he said finally, stayed in the water longer than usual.

Smart.

There was no admiration in his voice, just professional assessment.

Smart runaways were more challenging, but they always made mistakes eventually.

Everyone did.

Fear and exhaustion and hunger eroded judgment made people careless.

It was inevitable.

They followed the river downstream for two miles before the dogs picked up the scent again at a point where the bank was trampled with footprints, bare feet, woman-sized and child-sized, clear as day in the mud.

The dogs went wild, baying and straining at their leashes, and Crenaw gave them their head, letting them run while the mounted men followed.

The trail led away from the river now into the coastal marshlands.

And here the pursuit became more difficult.

The ground was uncertain, shifting between solid hammocks and treacherous mud that could swallow a horse up to its chest.

The sawrass grew taller than a man in places dense enough to hide an army.

The channels of open water wound through the landscape in patterns that seemed to have no logic, deadending or branching in ways that defied navigation.

Crenaw’s confidence began to erode slightly as the afternoon wore on and the trail became more difficult to follow.

The dogs kept losing the scent, finding it again, losing it, as if the runaways were moving through the water as much as over land.

By evening, when the sun was sinking toward the horizon, and painting the marsh grass golden red, they still hadn’t found them.

Crenaw called a halt, his jaw tight with frustration.

We’ll camp here, he said.

Resume at first light.

They can’t have gone far.

Woman and child in this terrain, no supplies.

They’ll be desperate by morning.

But as darkness fell and the slave catchers made their camp on a hammock of solid ground, as they tied the dogs and built a fire and ate their rations, strange things began to happen.

One of the men, a heavy set brute named Bogs, saw something moving in the marsh grass, a shape that seemed human but moved wrong, too fluid, too fast.

He called out a challenge, his rifle raised, but when he fired, the shape was gone.

And in the morning they found the bullet embedded in a cypress trunk a h 100red yards from where he’d sworn he’d seen movement.

The dogs became agitated as full darkness arrived, whining and pulling at their ropes, their ears flat against their skulls.

One of them, the lead hound that had never shown fear in 10 years of hunting, began to howl in a way that made the men uncomfortable.

Not the baying of a dog on a scent, but something higher pitched, almost like a scream.

Crenaw kicked the animal into silence, but it continued to tremble.

its eyes rolling white with terror.

And then there was the fire.

Twice during the night it went out, despite there being no wind, despite the wood being dry and wellplaced.

Each time they relit it, and each time it burned normally for a while before suddenly dying, as if smothered by invisible hands.

The third time this happened, one of the men, a superstitious Irishman named Doyle, muttered something about hints and witchcraft, and though the others mocked him, Krenshaw noticed that no one was sleeping soundly.

He lay awake himself, staring up at the stars visible through breaks in the clouds, thinking about the girl.

10 years old, Garrett had said, but something about this chase felt different.

The trail was too clever.

The tactics too sophisticated for a panicked mother fleeing with a child.

It was as if they were being led, drawn deeper into terrain that favored the hunted over the hunters.

As if someone knew exactly what they were doing.

Miles away, hidden in a dense thicket on a hammock surrounded by water.

Celia and Zora huddled together.

They had no fire, no shelter beyond the interwoven branches above them.

No food except the cornmeal mixed with marsh water into a thin paste.

Celia was exhausted, her feet bleeding from cuts sustained while moving through the saw grass, her muscles screaming from hours of wading through chestde water while helping Zora stay afloat.

But Zora seemed almost energized.

Her eyes glowed in the darkness.

Or perhaps it was just a trick of the starlight, and she was whispering words that Celia didn’t understand, her hands moving in patterns over the small objects she’d arranged in a circle around them, the contents of Ru’s bag, laid out with ceremonial precision.

Bones and roots and herbs, and in the center, something that Zora had added herself, a lock of her own hair, twisted with marsh grass into a small figure.

“What are you doing, baby?” Celia whispered, though part of her didn’t want to know.

Didn’t want to confront the stranges of her own daughter.

“Zora didn’t look up from her work.

Making them see things that aren’t there,” she said simply.

“Making them feel things, making them afraid.” Her voice was calm, matter of fact, as if she were describing the most ordinary task in the world.

“They’re hunting us with dogs and guns, so I’m hunting them with shadows and dreams.” The second day of the hunt began badly for Crenaw and his men.

When dawn broke pale and cold over the marshlands, they discovered that two of the dogs were gone.

The ropes that had secured them lay on the ground, not broken or chewed through, but untied.

The knots carefully loosened as if by human hands.

The remaining four dogs refused to track, cowering and whimpering despite their master’s curses and kicks.

The lead hound that had in the night was found dead, its body stiff and cold, though there were no marks on it, no signs of violence or disease.

It simply looked as if the animal had been frightened to death.

Doyle, the Irishman, wanted to turn back.

“This ain’t natural,” he said, his voice tight with fear, barely concealed as bravado.

“Something’s wrong here.

It’s like the swamp itself.

Don’t want us finding them.

The other men laughed at him, but the laughter sounded forced, hollow in the morning mist that rose from the water in ghostly columns.” Crenaw’s face was grim as he examined the dead dog, running his hands over its body, finding nothing that explained its death.

20 years of hunting runaways and he’d never lost a dog like this.

Never had animals refuse to track.

Never had that crawling sensation at the back of his neck, the primitive instinct that warned of danger he couldn’t see or name.

But he was not a man who allowed superstition or unease to interfere with business.

And this was business.

The Witors were paying him $50 for the woman’s return and 25 for the girl.

Good money worth a few days of discomfort in difficult terrain.

We keep going, he said flatly.

Dogs or no dogs, we can track them ourselves.

They’re leaving signs.

Broken grass, footprints, disturbed mud.

They’re human, not ghosts, and humans make mistakes.

But even as he said it, he wasn’t entirely certain he believed it anymore.

They pressed deeper into the marshlands, following a trail that seemed almost too easy to read now that the dogs were gone.

Footprints appeared in convenient places, as if pointing the way.

Broken branches marked passages through dense vegetation.

It should have made Krenshaw suspicious.

It did make him suspicious, but there was nowhere else to go, no other trail to follow.

The landscape had narrowed their options, channeling them along specific paths, between expanses of water too deep to cross.

By midday, they had entered a part of the marsh that seemed different from what they traveled through before.

The water here was darker, almost black, and it smelled of decay and old earth.

The trees grew strangely, their trunks twisted, and their branches reaching out at odd angles like arthritic fingers.

The silence was profound.

No birds called, no insects buzzed.

Nothing moved except the hunting party and the slow ripples their passage created in the still water.

It was Bogs who first reported seeing her.

They had stopped to rest the horses and eat cold rations when he let out a shout and pointed toward a thicket about 50 yard away.

There, I saw the girl.

She was standing right there watching us.

Everyone turned to look, rifles raised, but there was nothing visible in the thicket.

Krenshaw spurred his horse forward, crashing through the shallow water toward where bogs had pointed.

When he reached the spot, he found nothing.

No footprints, no signs of passage, no broken vegetation, just dense growth and dark water, and that oppressive silence.

“You’re seeing things,” one of the other men said, but his voice lacked conviction.

I saw her, Bogs insisted, his face flushed, clear as day, a girl, dark-skinned, wearing a ragged dress.

She was just standing there staring at us.

And her eyes, he stopped, seeming to struggle with how to describe what he’d seen.

Her eyes glowed like an animal’s eyes in lamplight, but gold instead of green.

If you’re captivated by this tale of resistance, born from desperation and something older than slavery itself, make sure you’re subscribed to this channel.

Hit that notification bell so you don’t miss what happens next and drop a comment about what you think Zora’s powers really are.

Are we witnessing hudoo? Something spiritual or simply the power of belief weaponized against oppressors? Krenshaw said nothing, but his hand tightened on his rifle.

He’d heard stories of course all slave catchers had stories of runaways who could curse their pursuers, who knew root work and conjure, who could call on spirits to confuse and misdirect.

He’d always dismissed such tales as superstition, the desperate fantasies of ignorant people looking for explanations when runaways got lucky or hunters made mistakes.

But something about this chase was different.

The dead dog, the untied ropes, the way the trail seemed to lead them in circles and now bogs.

Seeing things, they continued, but the mood had shifted.

The men rode closer together now, their eyes scanning not just the ground for tracks, but the shadows between trees, the dark places in the thickets, anywhere something might be hiding and watching.

The remaining dogs stayed close to the horses, no longer ranging out ahead as hunting dogs should, their tails tucked and their bodies tense with anxiety.

As the afternoon wore on toward evening, more incidents occurred.

One of the horses threw a shoe, though it had been freshly shaw just days before, and the terrain wasn’t particularly rocky.

When they stopped to examine it, they found the nails had simply worked loose, all of them at once, as if pulled out by invisible fingers.

Another man, quiet fellow named Porter, began complaining of a headache that rapidly worsened until he was doubled over in his saddle, groaning with pain.

The agony lasted perhaps 20 minutes and then vanished as suddenly as it had come, leaving him pale and shaken, and the sightings continued.

Each man, at different times, reported seeing the girl, sometimes close, sometimes far away, always watching with those strange eyes.

She appeared and disappeared like smoke.

There one moment and gone the next, impossible to pursue or corner.

Crenaw never saw her himself, which somehow made it worse.

made him wonder if his men were losing their minds, or if something was deliberately showing itself only to them, playing with them like a cat with mice.

By the time they made camp that second night, the party had traveled perhaps 10 mi deeper into the marsh, and seemed no closer to catching their quarry than they had been at the start.

Krenshaw studied his rough map by fire light, trying to make sense of their path, and realized with growing frustration that they doubled back on themselves at least twice, had circled landmarks they’d already passed.

“Either he’d been navigating poorly, which he didn’t believe, or something had been subtly leading them astray, making them lose direction without quite realizing it was happening.

“We should turn back,” Doyle said again, his earlier fear now ripening into open dread.

“This isn’t worth the money.

There’s something wrong with that girl.

Something unnatural.

We keep chasing her, we’re going to end up dead in this god-forsaken swamp.

No one’s dying, Krenshaw snapped.

But even he could hear the uncertainty in his own voice.

We’re professional hunters.

We don’t get spooked by shadows and coincidence.

That dog didn’t die of coincidence, Bogs muttered.

And I know what I saw.

That girl is conjuring against us.

My grandmother was from Louisiana told me stories about hoodoo women who could enough.

Crenaw’s voice was sharp as a whip crack.

I don’t want to hear any more superstitious nonsense.

We are dealing with a runaway slave and her child, nothing more.

Whatever’s happening can be explained by exhaustion, bad water, and the heat playing tricks on your minds.

But that night, as he lay awake, listening to the sounds of the marsh, the distant splash of something large moving through water, the calls of night birds that sounded almost human, the rustling of unseen creatures in the darkness beyond their fire, Krenshaw found himself thinking about all the stories he’d dismissed over the years, about slaves who claimed to have protections against their masters, about root workers who could curse white men and make them sicken, about the African practices that had survived the middle passage and lived on in secret, passed down through generations, waiting for moments like this to manifest their power.

He thought about the girl’s grandmother, the one Garrett had mentioned in passing, sold away years ago, but known to practice what they called witchcraft.

He thought about how the enslaved people had their own invisible infrastructure, their own systems of knowledge and resistance that existed beneath and despite the machinery of slavery.

He thought about how arrogant he’d been to assume that guns and dogs and white skin gave him automatic dominance over people who had been developing survival strategies for generations.

And for the first time in 20 years of hunting human beings, Silas Krenshaw felt something approaching fear.

Miles away in a different part of the marsh, Celia and Zora had reached what might generously be called shelter, a small island of solid ground, perhaps 50 ft across with a natural hollow beneath a massive live oak whose branches drooped so low they nearly touched the water.

They had found wild pimmens and eaten them despite their astringent taste, had drunk their fill from a freshwater spring that bubbled up clear and cold from the ground, had even managed a few hours of sleep, curled together beneath the oak’s protective canopy.

Zora’s ceremony from the previous night had left her exhausted, but there was a fierce satisfaction in her young face as she told her mother about the visions she’d sent the slave catchers.

“I made them see me,” she explained, her voice quiet, but intense.

Not really me, but an image of me.

I put it in their minds, made them look where I wanted them to look, while we went somewhere else, and I made them feel afraid.

I reached into their hearts and squeezed.

Celia listened with a mixture of pride and terror.

This was her daughter, her baby, but also something else.

something that had been born into her, but perhaps came from somewhere beyond her, channeled through her bloodline from ancestors who had practiced these arts in Africa, before the chains, before the ships, before America had stolen her people and tried to remake them as property.

“Are we safe?” she asked, because that was all that mattered.

“Now “Can we keep running for a while?” Zora said, but they won’t give up.

The tall one, the leader, he’s strong, harder to reach than the others, and they have more men back at the plantation.

More dogs.

Even if we lose these hunters, they’ll send others.

She was quiet for a moment, her strange eyes reflecting the moonlight filtering through the oak leaves.

We need to get to the Union lines, the soldiers wearing blue.

I’ve seen them in dreams.

They’re coming closer, fighting the Confederate army.

If we can reach them, we’ll be free.

Really free under their protection.

How far? Celia asked, though she suspected she didn’t want to know the answer.

2 weeks, maybe three.

North and west from here across territory controlled by Confederate patrols and slave catchers through settlements where they’ll be watching for runaways.

It’s Zora trailed off and for a moment she looked like what she was a 10-year-old child, small and vulnerable and far from home.

It’s a long way, mama, and I’m tired using the power.

It takes something from me, makes me weak after.

Celia pulled her daughter close, feeling the girl’s heart beating against her own chest.

This miraculous and terrifying child she brought into the world.

Then we’ll rest when we can and be strong when we must.

She said softly.

We’ve come this far.

We’ll go farther.

We’ll reach those Union soldiers and we’ll be free, baby.

I promise you that.

Or we’ll die trying.

And at least we’ll die as people who fought, not as people who just accepted their chains.

They slept fitly that night, taking turns keeping watch, knowing that the slave catchers would resume their pursuit at dawn.

But something had shifted in the dynamic of the chase.

What had begun as a simple hunt, armed white men on horses pursuing a desperate mother and child, had become something else entirely.

The hunters were becoming the hunted, their confidence eroding with each strange occurrence, each inexplicable event, and the prey they’d thought so helpless was revealing itself to be far more dangerous than they’d imagined.

In the morning, Zora performed another ceremony before they left the Oak Island.

She arranged her objects in their circle again, bones and roots and herbs, and spoke words in a language that had no name anymore, that existed only in the genetic memory of people whose ancestors had been stolen from Africa two centuries before.

She took a strand of Spanish moss from the oak, and twisted it with her own hair, creating another small figure that she placed at the center of her circle.

Then she closed her eyes and went very still, so still that Celia couldn’t tell if she was breathing.

When she finally moved again, opening her eyes and beginning to pack away her objects, she looked drained, her face gray with exhaustion, but her voice was steady when she spoke.

“I’ve sent them something new,” she said.

“Not just visions this time, something deeper, doubt, fear, the feeling that they’re not hunters, but prey.

That something in this marsh is watching them and waiting.

It won’t stop them.

The leader is too stubborn for that, but it will slow them down, make them cautious, give us time.” “Is it wrong?” Celia asked suddenly.

what you’re doing to them.

I know they’re hunting us.

I know they’d chain us and drag us back or kill us if we fought.

But she struggled to articulate the question.

Is it wrong to use power this way? Zora looked at her mother with eyes that seemed far older than her years.

They made me property, she said quietly.

They said I was a thing to be bought and sold.

That my body and my labor belonged to them.

That I had no rights they were bound to respect.

They did this not because of anything I’d done, but because of the color of my skin.

They built a whole world on the idea that people like us aren’t fully human.

She paused, her jaw set with determination.

So, no, Mama, it’s not wrong to use every tool I have to fight them.

It’s not wrong to make them afraid the way they’ve made us afraid every day of our lives.

It’s not wrong to turn their own weapons against them.

They use violence and fear, so I use fear right back.

The third day of the hunt marked the beginning of Crenaw’s unraveling.

He woke before dawn to find Porter gone.

The man’s bed roll was empty, his horse still tethered with the others, his rifle leaning against a tree where he’d left it the night before.

They searched the immediate area, calling his name into the gray pre-dawn mist, but found nothing.

No signs of struggle, no footprints leading away, no blood or disturbed ground.

Porter had simply vanished, as if he’d never existed at all.

Doyle refused to go any further.

“I’m done,” he said, his hands shaking as he saddled his horse.

“You can keep the money.

I don’t care.

I’m not dying in this cursed place for some runaway slaves.

He rode off before Krenshaw could argue, heading back the way they’d come, or at least the direction he believed was back, leaving only Krenshaw and Bogs to continue the pursuit.

Bogs looked like a man balanced on the edge of breaking.

His eyes were sunken from lack of sleep.

His hands trembled when he tried to light his pipe, and he jumped at every sound.

“We should listen to Doyle,” he said quietly.

“Whatever that girl is, whatever power she’s got, it’s beyond us.

This isn’t like hunting regular runaways.

This is something else.

But Crenaw’s pride wouldn’t allow retreat.

He had never failed to return a runaway.

Never lost a chase.

And he wasn’t about to let his reputation be destroyed by a woman and a child.

No matter what tricks they were using.

One more day, he said, his jaw set in stubborn determination.

We give it one more day.

If we don’t find them by nightfall, we’ll head back.

The trail they followed that morning seemed clearer than before, almost as if it were deliberately laid out for them.

Footprints pressed deep into mud, broken branches pointing like arrows, even what looked like a scrap of cloth caught on a thorn bush.

All of it leading them deeper into a part of the marsh where the water ran slower and darker, where the trees grew so close together their canopies blocked out most of the sunlight, creating a perpetual twilight even at noon.

Crenaw knew on some level that they were being led.

But the alternative was to admit defeat, to turn back empty-handed, to face the questions and ridicule that would follow.

So he pressed on, following a trail that was almost certainly a trap because his pride demanded it.

They found the first charm around midday.

It was hanging from a low branch directly in their path, impossible to miss.

a small construction of bones and feathers and Spanish moss tied together with what looked like human hair and twisted into a shape that might have been a bird or a star or something else entirely.

Bogs refused to touch it, refused even to ride near it, forcing Krenshaw to dismount and cut it down himself.

The moment his knife severed the cord holding it to the branch, Krenshaw felt something shift in the air around him.

The temperature dropped suddenly, cold enough that he could see his breath misting despite the humid warmth of the day.

His horse winnied and pulled at its res, eyes rolling white with fear, and from somewhere in the dense vegetation surrounding them came a sound that was almost like laughter, high and clear and distinctly human, though there was no one visible in any direction.

“She’s playing with us,” Bogs whispered, his face pale, like a cat plays with a mouse before it kills.

She could probably kill us anytime she wants, but she’s enjoying watching us suffer first.

Krenshaw wanted to argue, to insist this was all superstitious nonsense.

But the words wouldn’t come because part of him, the part that had survived two decades in a dangerous profession by learning to trust his instincts, knew that Bogs was right.

They weren’t the hunters anymore.

They were being hunted, toyed with, led deeper into territory where they had no advantage, and their quarry held all the power.

They found three more charms over the next two hours, each one more elaborate than the last.

One was a circle of stones arranged on a small island with a crude doll made of corn husks placed in the center, its head twisted backward in a way that made Bogs physically sick to look at.

Another was carved into the bark of a massive cypress tree, symbols that meant nothing to Caw, but that seemed to pulse with significance, demanding interpretation.

The third was the worst.

A perfect circle of dead fish floating in otherwise clear water, arranged with such precision that it couldn’t possibly be natural, their eyes all oriented toward the center, where a single black feather floated on the surface.

She’s marking territory, Krenshaw said, trying to keep his voice steady, showing us she knows we’re coming, trying to scare us off.

It’s working, Bogs replied flatly.

By late afternoon, they had reached what appeared to be the heart of the marsh, a place where the water spread out into a wide, still pool surrounded by ancient trees, whose roots created a tangled maze both above and below the waterline.

The air here was different, heavier, charged with something that made the hair on the back of Krenshaw’s neck stand up.

And there, on a hammock of solid ground in the middle of the pool, they saw her.

Zora stood perfectly still, her ragged dress hanging loose on her small frame, her bare feet planted on the earth as if she’d grown there.

She was looking directly at them with those eyes, and Krenshaw could see now what Bogs had meant about them glowing.

They caught the fading light and reflected it back with an amber luminescence that was distinctly inhuman.

She wasn’t running, wasn’t hiding.

She was waiting for them, and the smile on her young face was not the expression of a frightened child, but of something ancient and powerful, and utterly without fear.

“There,” Crenaw breathed, raising his rifle.

“I’ve got her.” But even as his finger tightened on the trigger, even as he cited down the barrel at the small figure standing 50 yards away across dark water, he hesitated because shooting a child, even a slave child, even a runaway, was different from the abstract business of hunting.

It was one thing to track people down and return them in chains.

It was another to put a bullet in a 10-year-old girl’s body and watch her fall.

In that moment of hesitation, Zora moved, not running away, but raising her hands above her head in a gesture that looked like benediction or curse or both.

Her lips moved, speaking words that carried across the water despite the distance.

Words in that nameless language that predated English in this land, and the world around Krenshaw began to change.

The water of the pool started to move, rippling and churning though there was no wind.

The trees seemed to lean inward, their branches reaching down like grasping hands.

The light already dim beneath the forest canopy dimmed further as if the sun itself was being eclipsed.

And from the water, from the trees, from the earth itself, shapes began to emerge.

They might have been shadows, or they might have been more solid than that.

It was impossible to tell.

Human-shaped, but wrong.

Too tall or too thin, or moving in ways that bodies shouldn’t move.

Dozens of them rising from the dark water, stepping out from behind tree trunks, materializing from the air itself.

Some wore chains that rattled as they moved.

Some bore the marks of violence on their spectral forms.

Whip scars, brands, missing limbs.

All of them were moving toward Crenaw and Bogs with a slow, inexurable purpose.

Ghosts, Bogs whispered, his voice breaking.

She’s raising the dead, all the slaves who died in these marshes, trying to run, trying to be free.

She’s calling them up.

Whether they were truly spirits of the dead or elaborate hallucinations created by whatever power Zora wielded, the effect was the same.

Bogs screamed, a high, keening sound of pure terror, and turned his horse, spurring it back the way they’d come.

The animal needed no encouragement, bolting through the shallow water with its rider barely managing to stay in the saddle.

Krenshaw held his ground a moment longer, his rifle still trained on Zora, who stood watching him with those terrible eyes.

The shapes were closer now, close enough that he could see their faces, or the suggestions of faces, twisted with suffering and rage, close enough to reach out and touch him.

He fired.

The rifle’s report was deafening in the enclosed space, echoing off the water and the trees.

But even as the bullet left the barrel, even as he watched it cross the distance toward the small figure on the hammock, he knew it wouldn’t matter.

And he was right.

Zora didn’t move, didn’t flinch.

The bullet struck the earth at her feet, and she simply smiled.

A terrible smile that held no childhood in it at all, only power and vengeance, and a promise of worse to come.

Crenaw broke then, his legendary composure built over 20 years of hunting human beings, shattered like glass.

He wheeled his horse and fled, following the path Bogs had taken, riding as fast as the terrain would allow, branches whipping at his face, and water splashing up around his horse’s legs.

Behind him, he could hear them, the shapes, the spirits, whatever they were, moving through the marsh in pursuit, their chains rattling, their voices raised in wordless cries that spoke of centuries of suffering, demanding justice.

He rode for hours, or maybe just minutes.

Time had lost meaning in the panic of flight.

When he finally stopped, his horse lthered and trembling, he found himself alone in a part of the marsh he didn’t recognize.

No sign of bogs, no sign of the spirits, no sign of anything familiar, just endless water and trees and the growing darkness as evening approached.

He was lost, completely, utterly lost.

And for the first time in his adult life, Silus Krenshaw felt what the people he hunted must feel.

The terror of being prey, the desperate uncertainty of not knowing if the next moment would bring capture or death or something worse.

Meanwhile, Celia and Zora were miles away, moving steadily northwest through a different part of the marsh.

Zora had collapsed after her working, the effort of creating those visions having drained her completely.

Celia had carried her daughter on her back for the first hour, the girl’s weight negligible, but her importance infinite before Zora had recovered enough to walk on her own.

Did it work? Celia asked as they paused to rest on a fallen log.

Zora nodded weakly.

They won’t follow us anymore.

The tall one might survive the marsh if he’s lucky, but he won’t hunt runaways again.

I made sure of that.

Put something in his mind that he won’t be able to forget.

She looked up at her mother, and there were tears on her cheeks now.

The first tears Celia had seen her shed since they’d fled the plantation.

I’m sorry, mama.

I know what I did was terrible.

Frightening people like that making them see their worst fears.

But I couldn’t think of any other way to stop them.

Celia held her daughter close.

This child who was both victim and weapon, both innocent and terrible in her power.

You did what you had to do to keep us alive, she said softly.

In a world that treats us as less than human, we use whatever tools we have to survive.

Don’t apologize for that.

Don’t ever apologize for fighting back.

They rested for a few hours, eating the last of their cornmeal and drinking from a clear stream before continuing their journey as darkness fell.

The worst of the pursuit was behind them now, but the hardest part of their escape still lay ahead.

They had to cross Confederate controlled territory, avoid patrols and settlements, find their way to Union lines that were constantly shifting as the war progressed.

It was a journey that would take weeks, maybe months, and would demand everything they had.

But as they moved through the night, Zora leading the way with her uncanny sense of direction, Celia felt something she hadn’t felt in years.

Not just hope, but a kind of fierce joy.

They were free.

Not legally.

The law still considered them property and would until they reached Union protection or the Confederacy fell, but in every way that mattered in their hearts and minds and the choices they made, they were free.

They had taken their lives back from the people who claimed to own them.

And whatever happened next, no one could take that away.

Behind them, somewhere in the dark marsh, Silas Krenshaw huddled on a small island, his rifle clutched to his chest, jumping at every sound.

He would eventually find his way out, would emerge 3 days later, half starved and completely broken, his hair reportedly gone white from whatever he’d experienced.

He would never hunt runaways again.

When people asked him why, he would only say that some prey was too dangerous to pursue, that there were powers in this world that white men’s guns and dogs couldn’t overcome.

The story of the slave catchers who vanished into the Florida marshes, pursuing a woman and child would spread.

Some versions said the hunters had been killed by alligators or had drowned in quicksand.

Others whispered about hudoo and conjure, about a girl who could command spirits and strike white men down with curses.

The enslaved community would hear these stories and pass them along, adding their own details and interpretations, transforming Zora from a real child into a legend, a symbol of resistance that grew larger with each telling.

But the real Zora, the actual 10-year-old girl, was simply trying to survive another night of running, trying to get herself and her mother to safety, trying to live long enough to see what freedom actually looked like beyond the abstract idea of it.

She was powerful, yes, but she was also tired and scared and far from home.

She was both the legend and the child, both the weapon and the victim.

both the terror that haunted slave catchers dreams and the daughter who held her mother’s hand as they walked through darkness toward an uncertain future.

The journey north took 18 days and each one tested them in ways that made the pursuit by Cshaw seem almost simple in retrospect.

The slave catchers had been a single focused threat that Zora could confront directly with her powers.

But the landscape of wartime Florida and southern Georgia was a maze of dangers that couldn’t be frightened away or cursed into submission.

Confederate patrols on every major road.

Settlements full of suspicious white people who would report any black face they didn’t recognize.

Rivers too wide to wade and too dangerous to swim.

Stretches of open country where there was no cover and no way to hide.

They traveled mostly at night, sleeping during the day in whatever concealment they could find.

abandoned cabins, dense thickets.

Once in a cave where the darkness was so complete that Celia couldn’t see her own hand in front of her face.

They ate what they could.

Forage, berries, roots, once a rabbit that Zora had somehow called close enough for Celia to catch with her bare hands.

The girl’s powers manifested in strange and unpredictable ways during this period, as if the constant danger was forcing them to evolve.

She could sense when patrols were near, could guide them away from danger before it became visible, could sometimes, though not always, convince animals to approach or flee as needed.

But the power came at a cost.

Each use left Zora weaker, more drained, her young body struggling to channel forces it wasn’t quite ready to handle.

There were mornings when she couldn’t wake up, when Celia had to shake her for long minutes before her eyes would open.

There were times when her nose would bleed spontaneously, when her hands would tremble so badly she couldn’t hold anything.

The bag of roots and bones and herbs that Ru had given her was running low, and without those materials to focus her workings, the power became more difficult to control, more chaotic in its manifestations.

On the seventh night, they had their closest call since escaping the marshes.

They were following a creek northward, using the water to hide their scent and mask their footprints when they heard voices ahead.

White voices, male voices, speaking in the casual tones of men who felt completely secure.

Celia pulled Zora into the shadows beneath an overhanging bank just as a Confederate patrol came into view.

Six soldiers in gray uniforms, their rifles slung over their shoulders, moving along the creek bank in the same direction Celia and Zora had been traveling.

They were so close that Celia could have reached out and touched the last man’s boot as he passed.

She held her breath, one hand clamped over Zora’s mouth, though the girl hadn’t made a sound.

Both of them pressed flat against the muddy bank while the patrol walked by, not 5 ft away.

The soldiers were talking about the war, complaining about their officers, speculating about when they might get leave, debating whether the Yankees would push this far south.

One of them stopped directly above where Celia and Zora were hiding.

Celia’s heart hammered so hard she was certain it could be heard.

The soldier was looking right at them, except he wasn’t seeing them.

His eyes passed over the shadows beneath the bank without recognition, as if there was nothing there to see.

After a moment, he spat into the creek and moved on, following his companions upstream.

When they were finally gone, when the sound of their voices had faded completely, Celia let out the breath she’d been holding, and looked at her daughter.

Zora’s eyes were closed, her face tight with concentration, sweat beading on her forehead despite the cool night air.

“Did you?” Celia began.

“Made us shadows,” Zora whispered, her voice barely audible.

Made their eyes slide past without seeing.

“But Mama, I can’t do it again tonight.

I’m too tired.

We have to find somewhere safe to rest.” “They found an abandoned smokehouse a mile from the creek, its door hanging open, and its interior wreaking of old meat and smoke.

It wasn’t comfortable, but it was shelter.

and more importantly, it was hidden.

They slept there through the day, taking turns keeping watch, and when night fell again, they continued their journey with renewed caution.

The landscape was changing as they moved north.

The marshes and coastal swamps gave way to pine forests and red clay hills.

The air became slightly cooler, the vegetation less tropical.

They were entering territory where the war was more actively being fought.

They could hear artillery in the distance, sometimes see smoke from fires on the horizon, occasionally stumble across the aftermath of skirmishes, trampled ground, abandoned equipment, once a grave marker hastily carved with a name and date.

On the 11th day, they encountered other runaways.

It was pure chance.

Both groups had chosen the same grove of trees to rest in during the daylight hours, and they discovered each other when a man’s snoring had woken Celia from an uneasy sleep.

There were four of them.

Two men, a woman, and a teenage boy.

All from a plantation near Vald Dosta.

They’d been running for 6 days and were heading for the same destination Celia and Zora sought.

The Union lines that were rumored to be somewhere near the Florida Georgia border.

The woman who gave her name as Sarah looked at Zora with something approaching awe.

I heard stories about you, she said softly.

About a girl who could do things, who sent slave catchers running back to their masters with their tails between their legs.

Thought it was just talk.

You know the kind of story people tell to keep their spirits up.

But it’s true, isn’t it? You can really do what they say.

Zora looked uncomfortable with the attention, with being recognized, with having her story transformed into legend before her eyes.

I can do some things, she said carefully.

But I’m just trying to survive same as you.

One of the men, an older fellow with gray in his hair and scars covering his arms, shook his head slowly.

Ain’t nothing just about surviving when you’re enslaved, he said.

Every day we live, every step we take toward freedom, that’s a victory against people who want us dead or broken.

And if you got special gifts that help you fight back, that’s a blessing.

Don’t diminish it.

They traveled together for the next 3 days.

The larger group providing safety and numbers, while Zora’s abilities helped them avoid patrols and navigate difficult terrain.

It was good to be with others, to share the burden of watchfulness, to have adult men who could help carry Zora when she was too exhausted to walk.

Sarah shared what food they had.

Some dried pork stolen from their plantation, hard biscuits that were barely edible but filled the stomach.

The teenage boy, who was named Marcus and rarely spoke, seemed particularly drawn to Zora, staying close to her as they traveled, as if proximity to her power might somehow protect him.

On the 14th night, they reached a river, not one they could wade across, but a wide, swift flowing body of water that would require swimming.

None of them knew exactly which river it was.

Geography was uncertain.

Maps were things white people had and slaves didn’t.

And the landscape of wartime was constantly shifting.

But on the far bank, visible in the moonlight, they could see what looked like military fortifications, earthworks, and wooden palisades that could belong to either Confederate or Union forces.

We have to know who holds that position before we try to cross.

The older man said, “Cross to Confederate soldiers.

They’ll shoot us or send us back to our masters.

Cross to Union soldiers.

We might be free.

“How do we tell?” Celia asked, though she suspected she already knew the answer.

“Someone has to get close enough to see their uniforms, hear them talk, figure out which side they’re on.” He looked at the dark river at the fortifications beyond.

It’s dangerous.

If they’re Confederates, and they spot whoever goes, that person won’t be coming back.

There was silence as everyone considered this.

The weight of the decision pressing down on them.

Finally, Zora spoke up, her voice quiet but steady.

I’ll go.

I can hide better than any of you, and if something goes wrong, I have ways of protecting myself.

No, Celia said immediately.

Absolutely not.

You’re 10 years old and you’re exhausted.

I won’t let you, Mama.

Zora took her mother’s hand.

And in that moment, she seemed older than her years, older than she had any right to be.

This is what we’ve been running toward for 2 weeks.

We have to know if those are our people or not, and I’m the only one who can do it without getting caught or killed.

You know, I am.

The argument that followed was brief because deep down everyone knew Zora was right.

Her abilities, whatever their source, however they worked, made her the logical choice for reconnaissance.

Finally, reluctantly, Celia agreed, but only on the condition that if Zora wasn’t back by dawn, the rest of them would assume the worst and find another way across.

They watched as the small figure slipped into the water, moving with surprising confidence for a child who’d been raised on a plantation nowhere near rivers this large.

Zora swam smoothly and quietly, barely disturbing the surface, her dark head occasionally visible in the moonlight before disappearing again.

Within minutes, she’d reached the far bank and vanished into the shadows near the fortifications.

The weight was agony.

Celia stood at the water’s edge, her eyes fixed on the spot where her daughter had disappeared, counting her own heartbeats, trying not to imagine all the terrible things that might be happening.

An hour passed, then two, the moon moved across the sky, and still there was no sign of Zora.

Sarah came to stand beside Celia, not speaking, just offering silent support.

The men maintained watch in different directions, alert for patrols on their own side of the river, and Marcus, the teenage boy, sat on the bank and cried silently, tears streaming down his face, though whether from fear for Zora or from the accumulated trauma of everything he’d experienced, Celia couldn’t tell.

Dawn was perhaps an hour away when Zora finally reappeared, emerging from the water with the exhausted smile on her face.

Their Union, she gasped, too tired to climb the bank without help.

The 54th Massachusetts colored regiment.

I got close enough to hear them talking, saw their uniforms, even spoke to one of the centuries.

He was black mama, a black man in a blue uniform carrying a rifle guarding a military position.

And when I told him we were runaways, he said to wait until full light and then come across openly.

He said they’d protect us.

The relief that flooded through Celia was so intense it was almost painful.

They had made it.

After 18 days of running, of hunger and fear and exhaustion, of near captures and constant danger, they had finally reached Union lines.

freedom, real, legal, protected freedom, was just a river crossing away.

They waited until the sun was fully up before attempting the crossing.

Partly to be visible to the Union centuries, and partly because Sarah couldn’t swim and needed daylight to see what she was doing.

One by one, they entered the water, helping each other across the current strong but not insurmountable.

As they swam, soldiers on the far bank watched them, rifles ready but not aimed.

And when they finally dragged themselves onto Union- held ground, dripping and exhausted, a black sergeant came forward to meet them.

“Welcome to freedom,” he said, and his voice was gentle despite his military bearing.

“You’re safe now.

The United States Army protects all people fleeing from slavery.

You won’t be sent back.

You won’t be harmed.

You’re free.” Celia collapsed onto the ground and wept.

Great wrenching sobs that she’d been holding back for weeks, for years, perhaps for her entire life.

around her.

The others were crying, too.

Sarah and Marcus and the two older men, all of them breaking down now that they could finally afford to feel the weight of everything they’d endured.

Only Zora remained standing, looking at the soldiers with those strange, luminous eyes, taking in the sight of black men in uniform, armed and respected, and fighting for their own freedom and the freedom of others.

The sergeant crouched down beside Celia, waiting patiently for her to compose herself.

When she finally looked up at him, he smiled.

We’ve got food, clean water, medical attention if anyone needs it.

There’s a camp about a mile from here where contraband, that’s what they call escaped slaves officially, are being processed.

You’ll be registered, given documentation, and then you can decide what you want to do.

Some folks join work details supporting the army.

Some head north to refugee camps.

Some even enlist if they’re able.

But whatever you choose, you’re under federal protection now.

And the war, Celia asked, her voice.

How much longer? The sergeant’s expression grew somber.

Hard to say.

Could be months, could be years.

The Confederacy is fighting hard, and they’ve got good generals and men who believe in their cause.

But we’ve got more men, more supplies, and we’ve got righteousness on our side.

Eventually, we’ll win.

And when we do, there won’t be any more slaves in this country.

Not one.

Over the following hours, as they were processed and fed and given clean clothes, as their names were recorded in official federal documents, the first time any of them had been documented as people rather than property, the story of their escape began to emerge.

The soldiers wanted to know how they’d evaded patrols, how they’d survived in hostile territory, how a woman and child had defeated experienced slave catchers.

Word of Zora’s abilities spread quickly through the camp, growing and transforming with each retelling until by evening she had become something like a celebrity.

Soldiers stopping by to see the girl who could work hudoo, who could strike white men down with curses, who had called up spirits to protect her escape.

Zora handled the attention with the same quiet dignity she’d shown throughout their journey.

She answered questions when asked, but didn’t elaborate, didn’t dramatize, didn’t try to make herself seem more powerful than she was.

And when a white officer asked her to demonstrate her abilities, she politely but firmly refused.

It’s not a trick, she said softly.

It’s not entertainment.

It’s something I do when I need to survive.

When my life or my mama’s life is in danger, I won’t do it just to prove I can.

The officer had been taken aback, not used to being refused by a black child, even a free one.

But the black sergeant who’d first met them at the river had stepped in smoothly, explaining that the girl was exhausted and needed rest.

The officer had accepted this and moved on.

But the interaction had made something clear.

Even in freedom, even under Union protection, the world was still complicated, still full of people who would see Zora as an oddity to be studied rather than a person to be respected.

That night, in a tent provided by the army, Celia and Zora lay side by side on clean blankets, the first real bedding they’d had in weeks.

Outside they could hear the sounds of the camp, soldiers talking and laughing, the winnie of horses, the clatter of equipment being moved and organized, the sounds of a world at war, but also the sounds of a world where they were no longer property, where their lives belong to themselves.

What happens now, Mama? Zora asked, her voice sleepy.

Celia thought about this question, about all the possibilities that had been closed to them just weeks ago and were now opening up.

We live, she said finally.

We figure out what freedom actually means, what we want to do with lives that are finally our own.

Maybe we go north, find a city where we can work and build something.

Maybe we stay and help the army, contribute to winning this war.

Maybe you learn to control your gifts better, find someone who can teach you more than Ru could.

Whatever we do, we do it as free people.

and the plantation.

Zora’s voice was very small now.

Master Witmore, Garrett, all of them.

Will they ever pay for what they did? Celia was quiet for a long moment.

I don’t know, baby.

There’s talk of justice after the war.

How of punishing the traitors who tried to tear this country apart to keep us enslaved, but talk is cheap, and powerful white men have a way of avoiding consequences.

Maybe they’ll pay, maybe they won’t.

But here’s what I do know.

We got free.

We took ourselves out of their power, and we did it using strength.

They didn’t even know we had.

That’s a kind of justice all by itself.

Zora nodded against her mother’s shoulder.

And within minutes, she was asleep, her breathing deep, and even her body finally able to rest without fear.

Celia stayed awake longer, thinking about everything that had brought them to this moment.

the birth under a moonless sky, the strange powers that had manifested in her daughter, the brutal years on the Witmore plantation, the desperate flight through marshes and forests, the slave catchers who’d hunted them and been defeated by a 10-year-old child wielding forces older than slavery itself.

Their story would spread.

She knew it was already spreading.

Soldiers would tell other soldiers who would tell civilians who would tell newspapers.

The tale would grow and change, would become legend and myth, would inspire other enslaved people to believe that resistance was possible, that the masters were not as invincible as they pretended to be.

Some versions would exaggerate Zora’s powers, would make her into a supernatural being rather than a child with strange gifts.

Other versions would diminish them, would explain away what happened through coincidence and luck.

But the truth, the real truth that Celia would carry with her for the rest of her life was simpler and more profound than any legend.

Her daughter had been born different, had been given powers by heritage and ancestry and forces beyond understanding.