Welcome to the channel Stories of Slavery.

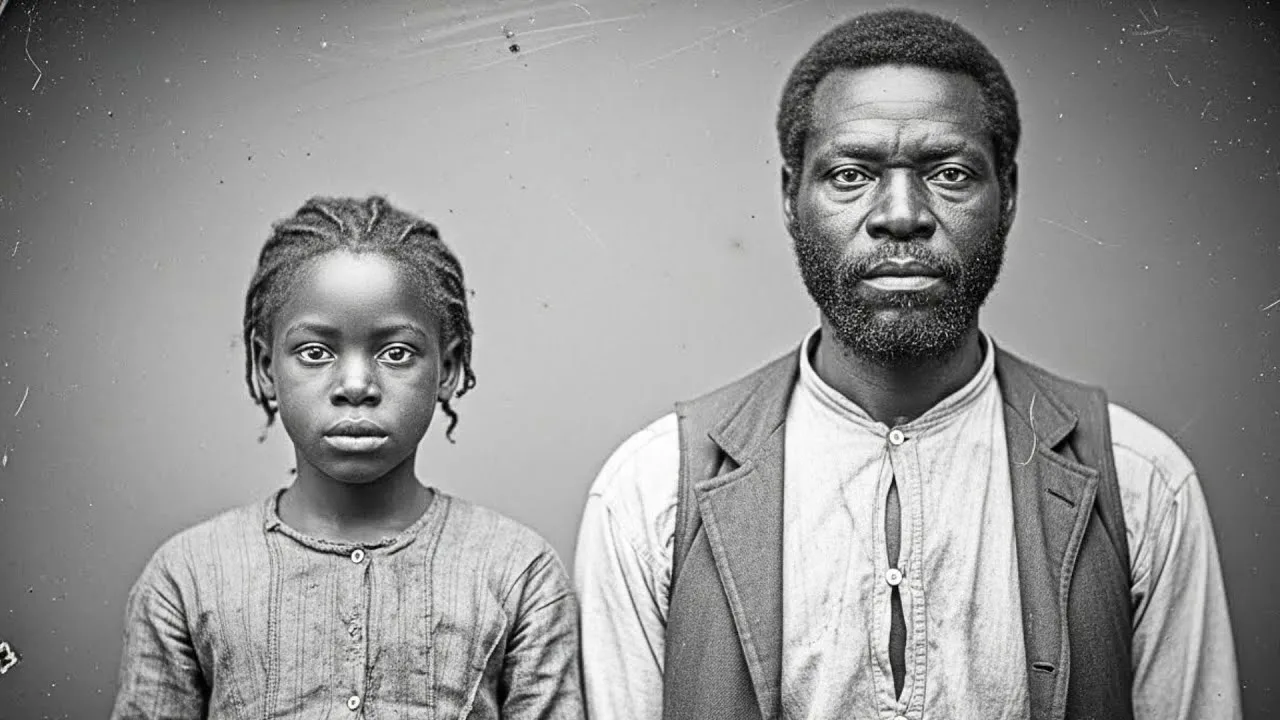

Today’s story takes us to 1867 where a black girl stumbled by pure chance upon a giant black man left to die chained to a tree in an isolated place.

She should have walked away.

Instead, she came back and what happened next shocked everyone.

This is a difficult and intense story rooted in racism, fear, and survival.

So, take a moment, breathe, and listen carefully.

Before we begin, subscribe and write in the comments which city and country you’re listening from.

Your participation helps keep these stories remembered instead of buried.

Let’s begin.

In the spring of 1867, somewhere deep in the backwoods of rural Georgia, a man named Samuel was being led to his death.

He was 6′ 8 in tall with hands the size of dinner plates and a back that carried scars like a road map of suffering.

Each line told a story of 23 years spent in chains.

23 years of cotton fields stretching to the horizon of sun that burned the skin and cold that crept into the bones during winter months when slave quarters offered little protection from the elements.

Samuel had been born into slavery in 1844.

3 years before his mother died during childbirth with his younger sister, who lived only 2 days before joining her mother in whatever lay beyond this world of suffering.

He never knew his father, though he’d heard whispers that the man had been sold south to Mississippi when Samuel was still an infant.

What Samuel did know intimately was the rhythm of plantation life, the crack of leather against skin, the hollow feeling of hunger that never quite left, even after meals of cornmeal and fatback, and the careful mask every enslaved person learned to wear to survive another day in a world that considered them property rather than people.

But Samuel had committed an unforgivable sin in the eyes of his owners.

A transgression that in the twisted logic of the antibbellum south and its immediate aftermath was considered more dangerous than theft, more threatening than running away, more intolerable than even striking an overseer in self-defense.

He had dared to look a white overseer directly in the eye.

Not with hatred burning in his gaze, not with defiance or challenge, or any of the things that white men constantly feared from the people they held in bondage, just with the quiet dignity of a human being who had forgotten for one dangerous moment that he was supposed to pretend he wasn’t one.

That single glance lasting perhaps two or three seconds on a hot afternoon while Samuel was hauling water buckets from the well to the fields cost him everything he had, which admittedly wasn’t much, but in that moment represented the difference between life and death.

The overseer, a man named Garrett Cole, had felt something crack inside his chest when Samuel’s gaze met his own.

It wasn’t fear exactly, though fear was certainly part of the cocktail of emotions that surged through him in that moment.

It was something worse.

Something that gnawed at the foundations of his entire world view.

Recognition.

the uncomfortable, undeniable awareness that the massive man standing before him in torn clothing and bare feet, his skin glistening with sweat from hours of labor under the merciless Georgia sun, possessed something Garrett himself lacked, and had always lacked, and would always lack, no matter how many men he commanded, or how many whips he cracked, or how many times he told himself he was superior by virtue of the color of his skin.

a kind of unbroken core that no whip could reach, no chain could bind, no degradation could destroy.

Samuel’s eyes held a soul that remained somehow intact despite everything the institution of slavery had done to crush it.

And in seeing that soul, Garrett was forced to confront the emptiness of his own.

Garrett had built his entire sense of self on a foundation of superiority that now in the aftermath of the civil war was crumbling faster than he could shore it up.

His father had owned slaves.

His grandfather had owned slaves.

And the natural order of things as he understood it placed him above men like Samuel by divine right and natural law and the simple fact of birth.

The preachers said it was biblical.

The politicians said it was constitutional.

The scientists with their calipers and charts said it was biological.

Garrett had never questioned any of it because questioning would have required him to examine his own life too closely, to wonder what he had actually accomplished beyond being born white in a world that rewarded whiteness above all else.

But in that moment of eye contact, lasting only seconds, but feeling like an eternity, the whole structure wobbled.

The lie became visible.

I became visible.

And Garrett, like so many frightened men throughout history, confronted with truths they cannot bear to acknowledge, did the only thing his limited imagination allowed.

He destroyed the thing that made him feel small.

The punishment was decided quickly with none of the pretense of justice that had sometimes, though rarely, characterized slave discipline in earlier times.

No trial, no hearing, no gathering of other slaves to witness the consequences of transgression as a lesson to them all.

Just a conversation between Garrett and the plantation owner, Thomas Rutherford, conducted over glasses of whiskey in a study lined with books neither man had actually read, but both kept for the appearance of education and refinement.

Rutherford was tired in a way that went beyond physical exhaustion.

The war had ended 2 years ago, but its effects rippled through the South like aftershocks from an earthquake that had shattered the old world without quite building a new one to replace it.

He had 87 former slaves still working his land under new contracts that weren’t really that different from the old arrangements, except now he had to pretend to pay them, and the pretense was expensive in ways both financial and psychological.

The cotton market was unpredictable.

Northern carpet baggers were sniffing around looking for land to buy cheap.

His own sons had died at Gettysburg and Chikamaga, their graves marked by wooden crosses somewhere in Pennsylvania and Tennessee.

Everything he had known was dying, and he didn’t have the energy to birth something new.

Samuel was strong, remarkably so, the kind of worker who could do the labor of two men without complaint.

Valuable, in other words, or at least he would have been valuable in the old days when such things were calculated in simple economic terms.

Under normal circumstances, Rutherford would have balked at the idea of killing productive property, would have argued for a whipping or a sale to a plantation further south, or some other punishment that preserved the value of his investment.

But these weren’t normal circumstances, and Samuel wasn’t technically property anymore, though the distinction between legal freedom and practical freedom was vast enough to swallow entire lives.

Garrett had been insistent, and Rutherford had learned over the years that sometimes it was easier to give men like Garrett what they wanted than to deal with the sullen resentment that followed refusal.

The world was changing in ways neither of them fully understood.

And in the face of that change, small acts of cruelty felt like attempts to hold on to something familiar, even if that familiar thing was monstrous.

He’s getting ideas, Garrett had said, swirling the amber liquid in his glass and watching the lamp light play through it.

Looking at me like he’s my equal.

Like the war changed something fundamental.

You let that spread.

You let that attitude take root.

And before you know it, they’re all doing it.

They’re all forgetting their place.

Then where are we? What’s to stop them from just walking off? from demanding real wages, from acting like they own themselves.

The questions hung in the air between them, unanswered, because both men knew there were no good answers anymore, just desperate attempts to maintain control in a world that was slipping through their fingers like water through a sie.

The 13th Amendment had been ratified in December 1865, officially ending slavery throughout the United States.

But the reality on the ground in places like rural Georgia was far more complicated.

The amendment contained an exception for punishment of crime and southern states were already exploiting that loophole through black codes that criminalized unemployment, vagrancy, and a host of other conditions designed to ensnare freed people and return them to conditions barely distinguishable from slavery.

Convict leasing was becoming a massive industry, allowing states to rent out prisoners to private companies for labor, creating financial incentives for mass incarceration of black men and women.

Ratherford had stared into his own glass for a long moment, watching his reflection distort in the curved surface, seeing a man he no longer quite recognized.

The face looking back at him was older than he felt, lined with worries and losses that had accumulated like sediment over the years.

Then he nodded once sharply, the gesture of a man making a decision he knows is wrong, but lacks the courage to resist.

“Take care of it,” he said quietly, his voice barely audible above the crackling of the fire in the hearth.

“But do it quietly.

Last thing I need is those bureau people asking questions, poking around, making trouble.

We’ve got enough problems without attracting that kind of attention.

He drained his glass and poured another, trying to wash away the taste of complicity that was already coating his tongue like ash.

The Freedman’s Bureau had been established by Congress in March 1865 to help formerly enslaved people transition to freedom, to provide education and legal assistance and protection from the kind of violence and exploitation that was already becoming commonplace across the South.

Officially called the Bureau of Refugees, Freed Men, and Abandoned Lands, it was intended to help four million newly freed people navigate a world that had never been designed to accommodate their freedom.

The bureau established schools, negotiated labor contracts, settled disputes, and occasionally prosecuted cases of violence against freed people.

But it was desperately underststaffed and underfunded with only 900 agents trying to serve the entire South.

In rural Georgia, bureau agents were few and far between, often covering territories of hundreds of square miles from offices in distant towns.

Local white power structures actively worked to undermine the bureau’s effectiveness, threatening agents, intimidating freed people who sought help and making it clear that anyone who cooperated with bureau investigators would face consequences.

The local sheriff was often related by blood or marriage to the plantation owners.

Judges and juries saw their primary duty as maintaining white supremacy rather than enforcing the law.

and witnesses had a way of disappearing or changing their stories when threatened.

But the bureau existed, a fragile presence that could occasionally shine uncomfortable light on the darkest corners of southern life, and its existence meant that certain things had to be done out of sight in places where witnesses were unlikely, and evidence could be easily disposed of.

So on a humid morning in late April, when the air was thick enough to chew and the sky held that particular quality of light that promises storms later in the day, Samuel was told he was being taken to help clear trees from a new field Rutherford was planning to open for planting.

He knew immediately it was a lie.

A man who has lived his entire life reading the subtle signs of danger the way others read newspapers develops instincts that operate below the level of conscious thought.

Samuel could read the air the way some people read books.

Could sense violence approaching the way animals sense storms.

The tension in Garrett’s shoulders held too rigid, betraying nervousness beneath the bravado.

The way the two other men accompanying them, poor whites who hired themselves out for jobs nobody else wanted to do, kept their hands near their guns, fingers twitching with barely contained anticipation.

The fact that they were heading deeper into the pine forest that bordered Rutherford’s property, away from any actual fields, away from the areas where work crews might be operating, away from eyes and ears and the possibility of witnesses.

Samuel had seen men taken away like this before during the war years when the threat of union sympathizers and slave rebellions made plantation owners paranoid and trigger happy.

Those men never came back and the official story was always that they had run away though everyone knew better.

Still, he went because the alternative was to die right there in front of the slave quarters with everyone watching.

And at least walking gave him time to think, time to pray, time to prepare his mind for whatever was coming.

The forest grew denser as they walked, the cultivated areas giving way to wilderness that had stood relatively untouched for generations.

The morning sun filtered through pine branches in dusty shafts of light that cut through the shadows like golden knives.

Mosquitoes hummed in clouds near a stagnant creek that smelled of decay and mud.

The water dark with tannins leeched from decaying vegetation.

They walked for nearly an hour, long past the point where the land could reasonably be cleared for planting, long past any pretense that this was about agricultural labor.

Samuel’s legs were strong from years of work, but the other men were breathing hard, sweating through their shirts, slapping at insects that swarmed around their faces.

Garrett led them with the determination of a man who has committed to a course of action, and refuses to reconsider, even as doubts begin to creep in.

His jaw was set, his eyes fixed on some point ahead, and he didn’t look back to see if Samuel was following, because he knew the two armed men bringing up the rear ensured compliance.

They walked until they reached a small clearing dominated by a massive oak tree that rose from the earth like a monument to time itself.

Its trunk was easily 12 ft around, gnarled and twisted with age, bark thick and deeply furrowed like the skin of some ancient creature.

Its branches spread like the fingers of a giant hand, reaching toward heaven, each limb thick as a normal tree, creating a canopy that cast the clearing in perpetual shade even at midday.

The tree had probably been standing for 200 years, perhaps longer, a silent witness to the slow march of history.

It had been there long before white men came to Georgia with their claims and deeds and weapons.

Back when the Muscoji Creek people had inhabited these lands and the forests had stretched unbroken from the Atlantic to the Mississippi.

It had stood through the forced removal of the Cherokee in 1838 when 16,000 people were marched westward on the Trail of Tears and 4,000 died along the way.

It had stood through the introduction of slavery to Georgia in 1751 when the prohibition against slavery that had been part of the colony’s founding was lifted and the plantations began to spread across the landscape like a cancer.

It had witnessed the passage of centuries, the rise and fall of empires, the endless human capacity for cruelty dressed up in whatever justifications the era provided.

This is the place,” Garrett said, his voice carrying a note of finality that made Samuel’s skin prickle despite the heat.

The two other men looked relieved that the walking was over, that they could finally complete whatever unpleasant business they’d been hired for, and returned to their own lives.

They began pulling heavy chains from a canvas sack, chains that clinkedked and rattled with a sound Samuel knew too well, having heard it every day of his life in one form or another.

The sound of Metal on Metal was the soundtrack of slavery, the constant reminder of bondage that accompanied fieldwork, punishment, transportation every moment of every day.

These were logging chains, the kind used for dragging massive timbers through the mud when roads needed to be cleared or bridges built.

Each link thick as a man’s thumb and forged from iron that would outlast flesh and bone and memory.

They were heavy enough that the two men struggled under their weight, grunting as they pulled them from the bag and let them fall to the ground in coils that looked like some industrial serpent.

Samuel looked at the tree, then at the three men, then at the heavy chains they were arranging on the ground.

He understood in that moment exactly what was going to happen, and the understanding brought a strange calm over him.

He could have fought.

He was stronger than all three of them combined.

His body honed by decades of labor that would have killed smaller men.

His hands could snap a man’s neck like a chicken bone.

His arms could crush ribs.

He could probably have killed at least two of them before the guns came out.

Could have died fighting rather than submit to whatever they had planned.

There was even a chance, however slim, that he could have killed all three and escaped into the forest.

But they had guns, pistols tucked into their belts, and a rifle leaning against a nearby tree, loaded and ready.

And even if by some miracle he killed all three of them, where would he go? He was in the middle of nowhere, miles from any town, hours of walking from the nearest road.

He was in Georgia in 1867, a state where his face would mark him as suspicious to anyone who saw him, where freedom was a word without much practical meaning for someone who looked like him, and had no papers to prove his status.

There were no safe places, no friendly faces, no underground railroad anymore because the war that had supposedly ended slavery had also destroyed the networks that had helped people escape it.

The roots north were closed.

The safe houses were abandoned or burned.

The conductors were dead or scattered.

So he stood there while they wrapped chains around his torso and the tree trunk, pulling them tight enough to restrict movement, but not quite tight enough to cut off breathing, at least not immediately.

Heavy iron links, each one thick as a man’s thumb.

cold.

Despite the morning heat, carrying the weight of industry and bondage, and all the ways humans had learned to control other humans, the chains made a specific sound as they settled against his body, a sound that would haunt whatever remained of Samuel’s life, a kind of musical clanking that seemed obscene in its ordinariness.

They wrapped them around and around, creating layers of metal that transformed him from a person into a fixture, an object bound to the tree as surely as the tree itself was bound to the earth.

The chains crossed over his chest, pinned his arms to his sides, wrapped around his waist and thighs.

They left his legs relatively free, enough that he could stand, but not walk, not sit completely, not do anything but remain upright against the tree like some grotesque decoration.

The chains were padlocked in three places, heavy iron padlocks that clicked shut with a finality that seemed to echo through the forest.

Each click like a door closing on possibility.

“You’re going to die here,” Garrett said, stepping close enough that Samuel could smell his breath.

a mixture of tobacco and rotting teeth, and the particular sourness that comes from a stomach ruined by cheap whiskey, consumed in quantities meant to drown conscience.

His face was inches from Samuel’s, close enough that Samuel could see the broken blood vessels in his nose, the yellow tinge to his eyes, the way his lips trembled slightly despite his attempt at confident cruelty.

Slow.

Real slow.

Nobody’s going to find you out here.

Animals will get to you eventually.

Probably start with your eyes.

That’s what they usually go for first.

The soft parts.

Crows, buzzards, maybe raccoons if they’re hungry enough.

By the time your bones turn up, if they ever do, nobody will know who you were.

Nobody will care.

You’ll just be another dead man in the woods.

Another piece of history nobody bothers to remember.

And you know what the best part is? Nobody’s even going to look for you.

They’ll think you ran off, headed north to try your luck with the Yankees.

Happens all the time now.

So, you’re just going to disappear like you never existed at all.

Samuel said nothing, refusing to give Garrett the satisfaction of fear or pleading or anger or any reaction whatsoever.

He kept his face carefully blank, the mask he had worn for 23 years firmly in place, denying this small, hateful man even the minor victory of a visible emotional response.

His silence was the only power he had left, the only act of defiance available to someone who had been stripped of everything else.

And he wielded it like a weapon.

He stared at a point somewhere past Garrett’s left shoulder, focusing on a particular patch of bark on the tree opposite, counting the ridges and valleys in the wood.

Turning his attention inward to a place where Garrett couldn’t reach, Garrett waited for a response, his anticipation almost palpable in the humid air, his body tensed like a dog waiting for a treat.

When none came, when Samuel simply stared past him with the expression of someone thinking about something far more important than the petty cruelty of small men, the overseer’s face twisted with frustration and disappointment.

He had wanted something, some final acknowledgment of his power, some validation that the act of killing a man slowly in the woods meant something, proved something about his superiority and Samuel’s inferiority.

Instead, he got nothing.

Just the quiet dignity of someone who refused to play the role assigned to him, who refused to be the cowering victim that would have made Garrett feel justified in his actions.

So Garrett spat at Samuel’s feet, the gesture of a child denied a toy, then turned and walked away, his boots crushing underbrush with unnecessary force, snapping twigs and kicking at stones like a man trying to reassert dominance through petty destruction.

The three men left, their voices fading as they disappeared back down the path they had carved through the forest.

Samuel heard them talking, something about stopping for water, about being back at the plantation by lunch, about what they would tell people if anyone asked where Samuel had gone.

Their voices grew fainter and fainter until they were absorbed completely by the ambient sounds of the forest.

Within minutes, Samuel could hear nothing but wind in the branches and the occasional call of a crow, harsh and mocking, as if the birds themselves were commenting on the absurdity and cruelty of human behavior.

The forest swallowed their footsteps completely, and Samuel was alone with the tree and the chains, and the slow understanding that he was going to die in this place, far from anything he had ever known or loved, with no one to witness his passing or mark his grave.

He tested the chains, pulling against them with all his considerable strength, hoping perhaps that they had been secured carelessly, that something might give.

They didn’t budge.

The iron links were thick and wellforged, the kind of chains designed to hold logs weighing thousands of pounds.

The padlocks were solid, manufactured in some northern factory and shipped south, ironically enough, by the same industries that had armed the Union army and helped end slavery, even as they profited from the tools used to maintain it.

The tree behind him was immovable, a living wall that had stood for generations and would stand for generations more, utterly indifferent to the human drama playing out against its bark.

Samuel’s arms were pinned to his sides by multiple loops of chain.

He could move his hands slightly, wiggle his fingers, but he couldn’t bring them together or reach any of the padlocks.

His legs were free enough to stand, but the chains around his torso prevented him from sitting or even bending his knees very far.

He was trapped in a standing position, and he understood with growing horror that this would become unbearable long before thirst or hunger killed him.

For the first time in years, Samuel prayed not to the God that white preachers talked about, the one who apparently approved of slavery and commanded servants to obey their masters, even when those masters were cruel.

Not the God who was quoted from southern pulpits to justify bondage, using cherrypicked verses from Ephesians and Colossians, while ignoring the parts about love and justice and treating others as you would want to be treated.

Samuel prayed to a different God.

the one his grandmother had whispered about when the overseers weren’t listening.

When the old people gathered in slave quarters after dark and spoke in hushed voices about things they weren’t supposed to remember.

The God who remembered Africa, who saw the ships crossing the middle passage and counted every person who died in chains in the hold, every body thrown overboard, every life destroyed by the machine of slavery.

The God who saw suffering and kept count.

Who stored up tears in bottles and wrote names in books.

Who promised that justice would come even if it didn’t come in this lifetime.

His grandmother had told him stories, fragments of belief that had survived the journey from whatever part of West Africa she’d been stolen from as a child.

Stories about ancestors who watched over their descendants.

About spirits in trees and water.

about a world beyond this one where the order of things was reversed and the last would be first and those who had suffered would finally know peace.

He prayed for a quick death, for the son to be merciful, for his heart to simply stop before the real suffering began.

He prayed that whatever lay beyond this life would be better than what he had known here.

He prayed for the people still working Rutherford’s plantation, still trapped in the quasi slavery of sharecropping contracts, still trying to build lives in a world designed to crush them.

He prayed for strength, not to survive because survival seemed impossible, but to die with dignity, to not break in these final hours, to maintain his humanity even as everything was stripped away.

The sun moved across the sky with agonizing slowness, each hour marked by the shifting shadows cast by the trees massive branches.

Samuel had spent his entire life working outdoors.

His body was conditioned to heat and exertion, but standing perfectly still in one position was a different kind of torture.

His legs began to ache within the first few hours, muscles cramping from the unnatural stillness.

He tried to shift his weight from one foot to the other, but the chains restricted even that small movement.

His back pressed against the rough bark of the tree, and he could feel it digging into his scarred skin, opening old wounds, creating new ones.

His mouth was dry as cotton within hours.

He had been given no water before the walk, and the morning’s exertion had left him dehydrated.

He caught himself opening his mouth toward the sky like a baby bird, hoping desperately for rain that didn’t come.

The sky remained clear and pitiles, that particular brilliant blue that Georgia springs produce, beautiful and indifferent to human suffering.

He slept standing up in brief fragments, his body jerking awake each time his knees tried to buckle and the chains caught his weight, biting into his flesh and jarring him back to consciousness.

Each time he woke, there was a moment of confusion, a second where he didn’t remember where he was or why.

And then reality would crash back like a physical blow.

The night brought some relief from the heat, but introduced new miseries.

The temperature dropped sharply once the sun went down, as it often does in the south, where humid days give way to cool nights.

Samuel’s thin shirt, soaked with sweat from the day’s heat, turned cold against his skin.

He shivered uncontrollably, his teeth chattering, his body trying desperately to generate warmth through movement it couldn’t make.

The chains grew cold, conducting heat away from his body, turning into bands of ice around his chest.

The forest at night was alive with sounds that seemed magnified in the darkness.

the hoot of owls, the rustle of small animals in the underbrush, the crack of branches that might have been deer or might have been something else.

Once he heard what sounded like a large animal moving through the forest not far from where he stood, something heavy enough to make the ground vibrate slightly with its passage.

He thought of bears, of wild boar, of the stories he had heard about animals attacking helpless prey.

and he waited in the darkness with his heart pounding for whatever was going to happen next.

But the animal, whatever it was, moved past without approaching the clearing.

The second day was worse in ways Samuel hadn’t imagined possible.

Thirst became everything, the only thought in his mind, the only sensation in his body.

His tongue felt thick and swollen, pressing against his teeth like a foreign object in his mouth.

His lips cracked and bled.

His throat was so dry that swallowing became painful, and he found himself swallowing compulsively anyway, unable to stop the reflex, even though each swallow felt like broken glass.

He tried to work up saliva, but his mouth was too dry, he thought about water constantly, obsessively.

The creek they had passed on the walk here, dark and stagnant, but still water.

The well at the plantation with its cool depths and the metal cup that hung on a chain, rain barrels due on grass, any moisture at all.

His body was beginning to shut down.

He could feel it happening.

Systems prioritizing and redirecting resources, trying to keep vital organs functioning even as extremities grew cold and numb.

He thought about his mother, tried desperately to remember her face.

He had been only seven when she died, and the years had eroded his memories like water wearing away stone.

He could remember her hands, rough from work, and the sound of her voice singing spirituals in the evenings, but her face remained frustratingly out of focus, a shape without details.

He thought about Lily, a girl who used to work in Rutherford’s big house, who had smiled at him once years ago when they passed each other on a path between the slave quarters and the kitchen.

It was a small moment, nothing more than a shared glance and a smile, but he had carried it with him like a treasure.

Ratherford sold her to a plantation in Alabama 6 months later, and Samuel never learned what happened to her.

He wondered if she was still alive, if she had married, if she had children, if she ever thought about the tall boy who had smiled back at her on that long ago afternoon.

He thought about freedom, not the complicated mess of what freedom actually meant in 1867, with its labor contracts and black codes and sharecropping arrangements that replicated slavery under new names.

But the simple dream version that people had whispered about in slave quarters throughout the south.

The dream of walking where you wanted without papers or permission.

Of eating when you were hungry.

Of keeping the money you earned.

Of belonging to yourself.

Of owning your own body and your own time and your own future.

Of reading books without it being illegal.

Of learning to write your own name.

Of choosing who to marry without needing anyone’s permission.

of raising children who were actually yours, who couldn’t be sold away at someone else’s whim.

Simple things that free people took for granted, but that seemed impossibly precious to those who had never had them.

By the third day, he was hallucinating, his brain trying desperately to escape a reality too painful to endure.

He saw his grandmother sitting on a tree branch directly above him, her legs dangling, humming a song he remembered from childhood.

She looked exactly as she had when he was small before age and labor bent her back and stole her teeth.

She smiled at him but didn’t speak, just kept humming that song.

Something about a river and a Jordan crossing.

And Samuel wasn’t sure if she was really there or if his mind was breaking under the strain.

He saw soldiers marching through the forest, both Union and Confederate, their forms flickering like ghosts, transparent in the filtered sunlight.

They marched in formation, rifles on shoulders.

And Samuel wondered if they were real soldiers who had died in these woods during the war, or if they were just his mind’s way of processing the fact that he was dying in a place where other men had died.

He saw the tree itself transform into a ship, its branches becoming masts, its trunk a hull, the chains around him turning into rigging, and he was somehow both chained to the tree and sailing on the ship at the same time.

And none of it made sense, but it all felt real.

He was dying.

That much he understood, even through the fog of dehydration and exhaustion.

His body was shutting down.

His heartbeat felt irregular, sometimes racing, sometimes slowing to an alarming degree.

His vision kept darkening at the edges, the world narrowing to a small circle of light directly in front of him.

His legs had stopped hurting, which he knew was a bad sign.

The body running out of resources to waste on pain signals.

He couldn’t feel his feet at all anymore.

And then he heard footsteps.

At first, he thought it was another hallucination, just another phantom produced by his dying brain.

But these footsteps were real.

He was sure of it.

Small, hesitant.

The sound of someone trying to move quietly through the underbrush, but not quite succeeding.

Through the fog clouding his mind, Samuel forced his eyes to focus, squinting against the afternoon sunlight that filtered through the oaks branches in golden shafts that should have been beautiful but felt like an insult.

A child stood at the edge of the clearing, frozen in place like a deer that had just realized it was being watched.

She was maybe 9 or 10 years old, though malnutrition made ages hard to judge among enslaved children.

Her skin was dark as midnight, so dark it seemed to absorb light rather than reflect it.

She wore a dress made from what looked like old flower sacks, the kind stamped with manufacturer’s names and logos, patched in several places with fabric that didn’t quite match.

Her hair was pulled back in tight braids that looked like they had been done several days ago and were starting to come loose at the edges.

In her hands she carried a tin bucket, the kind used for fetching water, its handle worn smooth from years of use.

Her feet were bare, calloused from walking on rough ground, caked with the red Georgia clay that stained everything it touched.

She froze completely when she saw him, her eyes going wide enough that Samuel could see white all around the irises.

Her mouth fell open in shock.

She looked at the chains wrapped around his body, at his face, at the clearing around them, processing what she was seeing with the quick intelligence of someone who had learned to assess threats.

Instantly, Samuel could see her mind working, understanding that she had stumbled onto something terrible, something dangerous, something she wasn’t supposed to witness.

He tried to speak, but his throat wouldn’t cooperate.

The words died somewhere between his brain and his mouth, and only a croak came out, a sound more animal than human.

The girl’s eyes went even wider at the sound.

She took a step backward, her body tensing to run.

Samuel tried again to speak, to say something that would keep her there, that would make her understand he needed help, but his voice was gone, destroyed by 3 days without water.

Another croak emerged, this one even worse than the first, and the girl turned and ran.

She moved like a rabbit fleeing a predator, all instinct and fear, her bucket banging against her leg as she disappeared into the forest.

Within seconds, she was gone, swallowed by the trees and underbrush, leaving only the sound of snapping twigs that faded quickly to silence.

Samuel’s heart sank, a weight settling in his chest that felt heavier than the chains binding him to the tree.

Of course, she ran.

What else would a child do when confronted with something like this? She was probably terrified, having seen a man chained to a tree like some kind of monster from a nightmare.

She would run back to wherever she had come from, and she might tell someone what she had seen, or she might be too scared to say anything.

If she did tell someone, they might come to investigate.

And if that someone was connected to Rutherford or Garrett, they would come finish what they had started.

Or maybe nobody would believe her.

Children saw strange things all the time, their imaginations turning shadows into monsters.

Maybe whoever she told would dismiss her story as fantasy or nightmare.

Either way, Samuel understood that his brief moment of hope, the possibility of rescue that had flared to life when he saw the child was gone.

He was going to die here.

And that was that.

He closed his eyes and waited for the end, for his heart to finally give out, for whatever came after this life to arrive and release him from suffering.

The afternoon sun continued its slow arc across the sky.

Birds called to each other in the canopy above.

The forest went about its business, utterly indifferent to the human drama playing out against the ancient oak.

But 6 hours later, as dusk was settling over the forest and painting everything in shades of purple and gold, Samuel heard footsteps again, the same small, hesitant footsteps.

He opened his eyes, barely able to believe what he was hearing, convinced it must be another hallucination.

But when he focused, he saw the girl was back.

She approached more cautiously this time, moving like someone approaching a wounded animal that might lash out unpredictably.

In her hands, she carried a jar, a mason jar with a metal lid, and what looked like a piece of cornbread wrapped in a piece of cloth.

She set them down about 10 ft away from him, carefully placing them on the ground like offerings at a shrine.

Then she turned and ran again, disappearing into the deepening shadows before Samuel could even attempt to make a sound.

He stared at the jar and the bread, his mind struggling to process what had just happened.

They might as well have been on the moon for all the good they did him.

The chains held him too tight to bend forward, kept him too close to the tree to reach out.

He couldn’t move his arms more than a few inches.

The food and water were tantalizingly close, but completely inaccessible.

Samuel made a sound that was something between a laugh and a sob, a noise that seemed to come from somewhere deep in his chest.

The cruelty of it was almost poetic.

To have water and food within sight, but unable to reach them, was somehow worse than having nothing at all.

It was hope offered and immediately revoked, mercy that was actually torture in disguise.

But he was wrong about that.

20 minutes later, after full darkness had fallen and the forest had transformed into a place of shadows and uncertain shapes, Samuel heard footsteps again for the third time that evening.

This time they approached slowly, carefully, without the panicked flight that had characterized the girl’s earlier departures.

Through the darkness, Samuel saw her small form emerge from between the trees, moving with the kind of cautious courage that seemed impossible in someone so young.

She crept all the way up to him, close enough that he could hear her breathing fast and shallow, her fear palpable in the night air.

Her hands were shaking so badly that Samuel could see them trembling even in the dim moonlight that filtered through the oak’s branches.

She picked up the jar of water from where she had left it.

She looked up at Samuel’s face, and even in the darkness, he could see her eyes huge and luminous, filled with fear and compassion and a determination that seemed to override every survival instinct, telling her to run.

Then, standing on her tiptoes and stretching as high as her small body would allow, she lifted the jar to his lips, her arms trembling with the effort of holding it up high enough to reach his mouth.

Samuel drank.

The water was warm and tasted like iron from being stored in a metal container, but it was the most beautiful thing he had ever experienced in his entire life.

It was life itself flowing into him.

Hope in liquid form.

Proof that miracles could happen even in the darkest moments.

He drank until the jar was empty and the girl’s arms were tired from holding it aloft.

Her small frame straining with effort.

Some of the water spilled down his chin and onto his chest.

And even that felt precious.

moisture touching his skin, reminding him that he was still alive, still capable of sensation, still human despite everything that had been done to dehumanize him.

When he finished, when the last drop had passed his cracked lips, Samuel managed to whisper two words, forcing them through a throat that felt like sandpaper, putting every ounce of feeling he possessed into those simple syllables.

Thank you.

His voice was barely audible.

horse and broken.

But the girl heard him.

She didn’t respond verbally, didn’t acknowledge his words with any sound of her own, but he saw her expression change slightly, saw something flicker across her face that might have been acknowledgment or might have been fear.

She set the jar down carefully, as if it were made of something precious despite being ordinary tin.

Then she grabbed the cornbread from where it lay wrapped in cloth on the ground.

She broke off a piece, her small fingers working at the dense bread, and held it up to Samuel’s mouth with the same careful attention she had shown with the water.

He ate, opening his mouth like a baby bird, accepting the food she offered.

It was dry and plain, the kind of cornbread that was a staple of poor people’s diets throughout the South, made with little more than cornmeal and water, and maybe a bit of salt if you were lucky.

But it was food.

It was life.

It was hope.

Samuel ate the entire piece in small bites, chewing slowly because his mouth was still too dry for easy swallowing, feeling the bread settle in his empty stomach like a blessing.

When the bread was gone, the girl gathered the jar and cloth, holding them carefully, and she disappeared into the darkness without a word, moving so quietly through the forest that within seconds Samuel couldn’t hear her footsteps anymore.

He stood there in the quiet forest, feeling water in his belly and the ghost of kindness on his lips.

And for the first time since being chained to the tree 3 days ago, he felt something other than despair.

He felt hope.

Fragile and uncertain, but hope nonetheless.

Someone knew he was here.

Someone cared enough to risk bringing him food and water.

Someone had seen his suffering and decided to act.

It was a small thing, maybe just a girl bringing water and bread.

But small things could mean everything.

Small acts of courage could change the course of history.

The girl came back the next morning, appearing from the southern path just after sunrise when the forest was still cool and full of bird song.

And she came the morning after that, establishing a pattern that would continue for days.

Always cautious, always quick, moving like a small ghost through the underbrush.

She never spoke, never stayed longer than a few minutes, never lingered long enough to be caught or seen by anyone who might have been watching.

But she brought water every time.

Sometimes in the same tin jar, sometimes in a different container, once in what looked like a hollowedout gourd.

Sometimes she brought bits of food, whatever she could scavenge without arousing suspicion.

A piece of cornbread, a few strips of dried meat, a handful of peacans, once a small sweet potato that she had apparently roasted in embers and carried to him wrapped in leaves to keep it warm.

Samuel learned to wait for her footsteps the way a plant waits for rain.

His entire being oriented toward those brief daily visits that meant the difference between life and death.

He began to understand her schedule, to sense when she would arrive based on the angle of morning light through the trees.

He learned to listen for the particular pattern of her movements, to distinguish her quiet footsteps from the sounds of animals or wind.

The food and water she brought weren’t enough to fully sustain him, weren’t enough to restore his strength or health, but they were enough to keep him alive, to keep his body functioning at a minimal level, to give him a chance at survival that shouldn’t have existed.

He never learned her name, though he desperately wanted to.

Every time he tried to ask, forming the question with his damaged voice during those brief moments when she was close enough to hear, she would put a finger to her lips and shake her head firmly.

The gesture was clear, even without words.

Silence was survival.

Talking was dangerous.

They both understood that truth at a bone deep level.

Names could be remembered and reported.

Conversations could be overheard.

But wordless mercy delivered in darkness and silence was harder to trace, harder to punish.

By the end of the first week, Samuel’s mind had cleared considerably from those first terrible days of dehydration and starvation.

The food and water the girl brought kept him alive, gave his brain enough glucose and hydration to function properly again.

His body was still screaming in pain from being chained upright for so many days.

His legs were swollen, the flesh tight and discolored, circulation compromised by his inability to move or elevate them.

His back was a mass of cramping muscles and open soores where the bark had rubbed his skin raw.

His wrists and ankles had deep grooves where the chains had pressed into flesh day after day.

But he was alive, and more importantly, he was thinking clearly again.

He began to observe everything with the attention to detail that had always characterized his approach to life.

Observation had been a survival skill during slavery.

The ability to read situations and people and environments had meant the difference between punishment and safety, between life and death.

Now he applied that skill to his current situation with systematic thoroughess.

The girl came from the south, always from the same direction, following what must be a regular path through the forest.

There was a trail there, barely visible to someone who didn’t know what to look for.

But Samuel could see it now that he knew where to watch.

A slight depression in the leaf litter.

Certain plants trampled more than others, broken branches at a consistent height that suggested regular passage.

She always glanced back the way she came, always checked over her shoulder multiple times during her brief visits.

Her body language screaming anxiety about being followed or discovered, which meant someone had sent her in this direction.

Someone expected her to be walking this path regularly, not to find Samuel.

That much was obvious from her initial shock when she first saw him, but for some other reason.

Water, probably.

Samuel thought there must be a spring or stream somewhere along this path and the girl had been tasked with fetching water.

Or maybe she was sent to gather herbs or wild plants, the kind of foraging work that was often assigned to children on plantations, something that required her to walk this path regularly enough that she could slip away to visit him without arousing suspicion about her absence.

He also observed that she was terrified, but still came back.

That kind of courage was rare, the ability to do something dangerous despite fear rather than in the absence of fear.

Samuel had seen grown men, hardened by years of abuse and labor, crumble under less fear than this child carried in her small body every time she approached him.

She knew the risks.

She understood that if she was caught helping him, she would face terrible punishment.

maybe even death.

And yet she kept coming back, kept bringing water and food, kept performing these small acts of mercy that required her to risk everything she had.

Who was she? Samuel wondered.

Where had she come from? What had her life been like that produced this kind of moral courage in someone so young? Did she have parents, siblings, family who would miss her if something happened? Did anyone know what she was doing? Was this entirely her own secret? Samuel wanted to know her story, wanted to understand the forces that had shaped her, but he also understood that knowing might be dangerous for both of them.

Sometimes anonymity was protection.

One morning, about 10 days after she first appeared, something changed in the girl’s behavior.

She approached as usual, moving with her characteristic caution, bringing water in the tin jar as she always did.

But this time, she didn’t run right away after giving him water and a few bites of food.

Instead, she walked around the tree, studying the chains with an intensity that suggested she was seeing them for the first time, despite having visited many times before.

She touched one of the padlocks with her small fingers, traced the curve of iron, examined how the links were wrapped around Samuel’s body and the tree trunk.

She walked the complete circle of the tree, her eyes moving over every detail, her mind clearly working on some problem that Samuel couldn’t quite grasp.

Samuel watched her think, watched the wheels turning behind her eyes, and he felt something shift inside his chest.

The girl wasn’t just bringing him food and water anymore.

She was planning something.

He could see it in the way she studied the chains, in the furrow between her eyebrows, in the way she bit her lower lip while considering options.

She was small, maybe 70 lb at most, probably less.

The chains weighed more than she did.

Each link was forged from iron that had probably come from a foundry in Pittsburgh or Birmingham, industrial-grade metal designed to hold massive loads.

The tree was immovable, an ancient oak with roots that went deeper than a house was tall.

But her eyes were moving over the chains with an intelligence that had nothing to do with size or physical strength, looking for weaknesses, considering possibilities, approaching the problem like a puzzle that could be solved with enough thought and effort.

She left without a word, disappearing into the forest as she always did.

But Samuel understood something had changed.

She was planning something.

And though he didn’t know what, though he couldn’t imagine what a small child could possibly do against iron chains and steel padlocks, he felt hope bloom in his chest like a flower opening to sunlight.

That night, it rained.

The storm came sudden and violent, the way spring storms do in Georgia, building quickly from a few rumbles of distant thunder to a full-on deluge that transformed the forest into a liquid world.

Lightning split the sky in branches of brilliant white, illuminating the clearing in flashes that burned after images into Samuel’s retinas.

Thunder shook the earth, deep booms that Samuel felt in his chest like a second heartbeat.

Rain came down in sheets, soaking Samuel in seconds, plastering his thin shirt to his body, running down his face and into his mouth.

He tilted his head back and opened his mouth, catching water on his tongue, drinking directly from the sky.

It tasted clean and pure, not like the metallic tang of wellwater or the stale flavor of water that had been sitting in containers.

This was fresh rain, and Samuel drank and drank, feeling it fill his mouth and run down his throat, more water than he could possibly swallow.

And through the rain, through the thunder and the howling wind, Samuel heard something that made his heart race.

Metal scraping against metal.

The sound was distinctive, even through the storm.

That particular shriek of iron on iron that Samuel had heard his whole life in various contexts.

He couldn’t see clearly through the downpour.

Rain was falling so hard that visibility dropped to almost nothing.

The world reduced to a gray wall of water punctuated by lightning flashes.

But he felt it.

Felt the chains shift slightly against his body.

Not much, just a minor adjustment, a slight loosening that could have been his imagination, except he knew it wasn’t.

The girl was out here in the storm, he realized with a shock.

She was behind the tree working on the chains, doing something to them that Samuel couldn’t see, but could feel.

The metal on metal sound continued, sporadic and irregular, sometimes stopping for long stretches before starting again.

Samuel wanted to tell her to stop, wanted to yell at her to go back to wherever she had come from, to get out of this storm, to stay safe, to not risk herself any further.

She was just a child.

She shouldn’t be out here in weather like this.

She could get struck by lightning or catch pneumonia or get caught by whoever might be out looking for her.

But he couldn’t speak loud enough to be heard over the storm.

And even if he could, he didn’t want to draw attention to their location.

So he stood there helpless, feeling the chains shift and listening to the sound of metal on metal beneath the roar of rain and thunder, hoping desperately that she knew what she was doing.

After what felt like hours, but was probably 20 or 30 minutes, the sound stopped.

The chains felt different somehow, looser.

Though Samuel was still completely trapped and unable to move in any meaningful way, the padlocks remained secure.

He could tell that without even checking, whatever the girl had done hadn’t freed him, but something had changed.

He could feel more give in the chains now, more ability to shift his body slightly within their constraints.

It wasn’t freedom, not even close, but it was something.

It was movement where before there had been none.

The girl didn’t come back for 2 days after that storm.

Samuel spent those days testing the chains with newfound energy, pulling and twisting and trying to understand exactly what she had done.

The padlocks were still secure, locked tight, keys probably hanging on Garrett’s belt or stored in a drawer somewhere on the plantation.

But the chains themselves had more play now, more slack than before.

He couldn’t escape, couldn’t pull free, but he discovered something miraculous.

He could sit by working his body carefully, by manipulating the chains in ways that would have been impossible when they were tighter.

Samuel managed to lower himself to the ground.

The relief was indescribable, almost overwhelming in its intensity.

For the first time in two weeks, Samuel sat with his back against the tree and the chains loose enough to allow him to bend his knees.

His legs shook uncontrollably as he lowered himself, muscles that had been locked in position for so long, protesting the change.

His knees nearly gave out completely, and for a moment he thought he was going to collapse in a heap rather than sit down in a controlled manner, but he made it, sinking slowly until he was seated on the forest floor, leaf litter and pine needles cushioning him slightly.

He sat there and nearly wept from the sheer relief of it.

His legs could rest now.

His back could relax slightly.

The pressure came off his feet and ankles.

It felt like heaven must feel like the answer to prayers he had stopped believing would be answered.

When the girl returned on the third day after the storm, she saw him sitting and she smiled.

It was the first smile Samuel had ever seen from her, a small expression that flickered across her face quick as a bird taking flight.

But it was there, a genuine smile of satisfaction and maybe even pride.

She had accomplished something difficult and dangerous, and it had worked.

Samuel smiled back, the gesture feeling strange on his face after so many days of pain and fear.

That night, alone in the darkness, with his body finally able to rest in a position that resembled something human rather than torture device, Samuel began to think not about dying, but about living, about what would happen if he actually survived this ordeal, about what he would do with whatever time remained to him in this life.

He had been left here to die quietly, to disappear from the world without witnesses or consequences, to become nothing more than a cautionary tale whispered in slave quarters about what happens when you forget your place, when you look a white man in the eye, when you dare to act like you’re human.

But he hadn’t died.

Against all odds, against every reasonable expectation, he was still alive.

And the reason he was still alive was because a child had seen him, had recognized his humanity in a moment when the world had tried to erase it, and had chosen to help despite every good reason to walk away.

She had risked her own life every single day to keep him breathing.

Had brought food and water and eventually tools to loosen his chains.

She had shown more courage and compassion than most adults Samuel had known in his entire life.

Why, Samuel wondered.

Why had she done it? Maybe she didn’t even know herself.

Maybe it was just human decency, that basic inability to walk past suffering without doing something about it.

Maybe she had lost people she loved and couldn’t bear to watch someone else die if she had any power to prevent it.

Maybe she was just impossibly brave, one of those rare individuals who does the right thing because it’s right, without needing complicated reasons or justifications.

Whatever her motivations, she had changed everything.

Samuel was no longer the man who had been chained to this tree two weeks ago, the man who had walked meekly to his execution because fighting seemed pointless.

Because where could he go? Because what difference would it make? That man had died somewhere around day three.

His spirit finally breaking under the weight of thirst and pain and despair.

The man sitting here now was different.

He had been remade by suffering, yes, but also by mercy.

By the daily miracle of a child who kept coming back by the slow understanding that even in the darkest places, humanity could survive.

He knew things Garrett didn’t think he knew.

23 years of forced labor on Rutherford’s plantation had taught Samuel things that free men took for granted, but that enslaved people turned into survival skills.

He knew the layout of every field, every barn, every outbuilding.

He knew which fields held cotton and which held corn, where the tobacco was planted, where the vegetable gardens were maintained.

He knew the schedules of patrols back when there had been patrols during the war to watch for runaway slaves and Union sympathizers.

He knew the names of every person living on the property, knew who could be trusted, and who would sell out their own mother for an extra ration of salt pork or a slightly less terrible work assignment.

He knew where the guns were kept in the big house and in the overseer’s cabin and in various storage buildings around the property.

He knew where Rutherford kept his money.

Not in a bank because Rutherford didn’t trust banks, especially not now that the Confederate currency he had accumulated was worthless.

He knew when people got up and when they went to bed.

He knew which dogs were vicious and which were friendly.

He knew which horses were fast and which were old and slow.

He knew where the roads went, which paths led to town, and which led to other plantations, and which deadended in swamps or thick forest.

He knew the rhythms of plantation life, the way a musician knows a familiar song, could predict what would happen and when, based on season and time of day, and a thousand other small factors that free people never had to consider.

Samuel also knew how to read people.

Not in the literal sense.

He had never been taught to read words on a page.

That skill was forbidden to enslaved people throughout the South by laws that made teaching slaves to read a criminal offense.

But he could read faces and body language and tone of voice with the precision of someone whose life had always depended on accurately predicting what powerful people were thinking.

He knew when someone was lying.

He knew when they were scared.

He knew when they were about to become violent.

He knew which appeals worked on which people, what arguments might sway them, what threats they took seriously, and what threats they dismissed.

It was a kind of emotional intelligence born from necessity, from being utterly at the mercy of others and needing to navigate that powerlessness without getting killed.

Most importantly, slavery had taught him patience.

The kind of bone deep patience that free people rarely developed because they rarely needed it.

Enslaved people understood that change came slowly or didn’t come at all.

That suffering had to be endured because there was no alternative.

That revenge, if it came, couldn’t be immediate and explosive, but had to be carefully planned and patiently executed because one mistake meant death.

Revenge doesn’t have to be quick, Samuel thought as he sat against the tree in the darkness.

His body finally allowed to rest, his mind working through possibilities and plans.

Revenge can be a crop you plant carefully, tend quietly, and harvest when the time is right.

You don’t rush crops.

You prepare the ground.

You plant at the right time.

You water and weed and protect the growing plants from pests and weather.

and then when the season is right, you harvest.

Rutherford and Garrett understood that principle when it came to cotton and corn, Samuel would apply it to something else entirely.

The next time the girl came, Samuel was ready.

“I need you to do something,” he whispered when she brought water, his voice stillarse, but stronger than it had been in weeks.

The girl froze completely at the sound of his voice.

It was the first time he had said more than thank you.

The first time he had initiated any kind of conversation beyond grateful acceptance of her help.

I need you to watch for me.

Samuel continued, keeping his voice as quiet as possible while still being audible.

When men come to this part of the forest, how many, which direction they come from, what they’re doing? He paused, letting the words sink in, watching her face for reaction.

I know it’s dangerous.

Everything you’ve already done is dangerous, but I’m going to get out of here somehow.

And when I do, I need information.

I need to know what’s happening on the plantation.

I need to know who’s doing what.

The girl’s eyes were huge.

Whites showing all around the dark irises.

She shook her head rapidly, a vigorous back and forth that suggested panic or refusal, or maybe both.

Samuel understood her fear.

what he was asking went beyond simple mercy.

Bringing food and water to a dying man was one thing, but actively spying for him was something else entirely.

That was participation.

That was conspiracy.

That was the kind of thing that got people killed slowly and publicly as a lesson to others.

I know, Samuel said softly, understanding flooding his voice.

I know what I’m asking.

And if you can’t do it, I understand.

You’ve already done more than anyone could expect.

You’ve saved my life.

But I need to know what’s happening out there if I’m going to survive this.

And I need help I can trust.

The girl stood perfectly still for a long moment, so motionless she might have been carved from stone.

Samuel could see her thinking, weighing options, considering risks.

She was young, but not naive.

She understood exactly what Samuel was proposing and exactly what it would cost if they were caught.

Finally, slowly, she nodded once, not a vigorous nod of enthusiasm, but a small, serious acknowledgement of commitment.

Then she turned and ran, disappearing into the morning light before Samuel could say anything else.

Over the next two weeks, a strange partnership formed between Samuel and the Nameless Girl, a relationship built entirely on gestures and whispers and mutual understanding that transcended the need for lengthy conversation.

The girl would visit each morning, as she had been doing, arriving with the regularity of sunrise itself, bringing food and water that kept Samuel’s body functioning at a level just above starvation.

But now she also brought information delivered through a complex system of communication they developed together out of necessity.

She would scratch drawings in the dirt with a stick, simple pictures that conveyed meaning.

Two vertical lines meant two men.

A horizontal line with marks along it indicated a path or road.

A circle meant the plantation house.

An X meant danger or something important Samuel needed to know about.

Sometimes she would use gestures, her small hands shaping meaning in the air.

Two fingers walking meant people moving.

A hand over her mouth meant secrets or silence.

Pointing in specific directions told Samuel where things had happened or where people had gone.

It was crude communication limited by their need for speed and silence, but it worked remarkably well once they both understood the vocabulary they were creating together.

Through this system, Samuel began to piece together what was happening on Rutherford’s plantation and in the surrounding area.

The girl brought news that seemed mundane on the surface, but that Samuel could interpret through the lens of his intimate knowledge of how plantations functioned.

She drew two men in the dirt, then made a gesture like drinking, then pointed west toward where the clearing was located.

Two men had come through the forest 3 days ago.

Samuel understood.

They had been drunk, stumbling, and loud, their voices carrying through the trees.

They had looked toward the tree from a distance, probably checking to see if Samuel was dead yet.

But they hadn’t approached closely.

Hadn’t wanted to see the details of what they had done.

hadn’t wanted to confront the physical reality of leaving a man chained to die slowly in the wilderness.

Garrett and one of his hired men, Samuel guessed, based on timing and direction, checking on their handiwork, making sure their secret execution was proceeding according to plan, verifying that the problem of Samuel’s existence was being quietly erased.

Except it wasn’t.

Samuel was still alive, still breathing, still thinking and planning.

And that single fact changed everything about what came next.

Altered the entire trajectory of events in ways that Garrett and Rutherford couldn’t have anticipated because they had made the fundamental mistake of assuming Samuel would simply die as planned.

The girl also brought information from the plantation itself, news she couldn’t possibly know was important, but that Samuel could contextualize in ways she couldn’t.

She drew the plantation house, then scratched out sections of it, then made a gesture of things falling or breaking apart.

Ratherford was selling parts of the plantation, Samuel realized, breaking up the land into smaller parcels, liquidating assets to raise cash.

Times were extraordinarily hard for plantation owners in the postwar south.

The cotton market was unpredictable, fluctuating wildly based on factors like global supply, competition from Egyptian and Indian cotton, and the disrupted labor systems that made southern agriculture far less efficient than it had been during slavery.

Northern investors were buying up land for pennies on the dollar, seeing opportunity in southern distress.

The old plantation aristocracy was dying a slow death, and men like Rutherford were desperately trying to salvage what they could from the wreckage of their world.

She drew a small house, then made angry gestures with sharp, violent movements, then pointed east toward where Samuel knew Garrett Cole’s cabin was located.

The angry gestures probably meant fighting or violence, domestic conflict that was becoming more frequent and more severe.

Garrett was drinking more heavily.

The girl seemed to be indicating through a series of gestures that Samuel interpreted as bottles being lifted to lips repeatedly throughout the day.

Garrett had always had a vicious streak Samuel knew from years of observation.

The man took out his frustrations on anything weaker than himself, his horse, his wife, the workers he supervised.

But the drinking was getting worse as Garrett’s world crumbled around him.

The hierarchy that had placed him above people like Samuel by virtue of nothing more than skin color was collapsing, and Garrett didn’t know how to exist in a world where that hierarchy wasn’t firmly established and enforced.

Through the girl’s gestures, Samuel understood that the violence in Garrett’s household was escalating dangerously.

His wife Mary, a thin woman Samuel had occasionally seen when she came to trade eggs or vegetables, was bearing the brunt of Garrett’s rage and fear.

Samuel filed that information away, understanding instinctively that Garrett’s increasing instability might be useful somehow, might create opportunities or vulnerabilities that could be exploited if Samuel was clever enough to see them and brave enough to act on them.

She drew a man in what looked like a uniform, then the plantation house, then made a gesture of writing with an imaginary pen.

A Freedman’s Bureau agent had visited recently, Samuel realized with a spike of interest that felt like electricity in his chest.

This must be Stevens, the man who stayed in the town about 15 mi away and traveled a circuit through rural areas, ostensibly checking on conditions for freed people.

The bureau had been established by Congress in 1865 with the idealistic mission of helping 4 million newly freed people navigate a world that had never been designed to accommodate their freedom.

In practice, bureau agents were desperately understaffed, chronically underfunded, and facing active violent resistance from local white power structures that saw them as invaders and threats to the racial order.

But they existed.

They represented federal authority in a region that had just lost a war to that same federal government.

And their presence, however limited and ineffective, meant that certain kinds of behavior had to be hidden rather than conducted openly as they had been during slavery.

The girl made gestures that Samuel interpreted as scales or balance, indicating justice or law, then pointed west toward town.

The local sheriff’s name was Morrison, and Samuel knew from years of plantation gossip that he was Rutherford’s cousin through marriage, related by blood, to the very people he was supposed to be policing impartially.

That relationship explained everything about how law enforcement functioned in this county.

Justice wasn’t blind here.

It had eyes that saw only what the plantation owners wanted it to see, that turned away conveniently when violence was committed against freed people, that focused laser-like on any hint of resistance or organization among the black community.

But perhaps most importantly for Samuel’s emerging plans, the girl brought information about the freed people working Rutherford’s land and living in the surrounding area.

Through her gestures and drawings, she indicated that people were organizing quietly, meeting in secret, sharing information, and building networks of mutual aid.

They gathered in the small wooden church on Sunday afternoons after services ended, staying behind while white overseers went home to their own families.

They shared information about labor contracts, comparing what different plantation owners were offering, helping each other understand the legal documents that most of them couldn’t read because teaching slaves to read had been illegal throughout the South, and literacy rates among freed people were consequently extremely low.

They were learning to navigate the brutal economics of sharecropping.

A system where former slaves worked land they would never own.

Giving a share of their crop to the landowner as rent.

Buying supplies on credit from stores the landowner often controlled either directly or through family connections and somehow ending each year deeper in debt despite working from sun up to sun down every day except Sunday.

It was slavery with extra steps and different paperwork.

But the freed people were learning those steps, were figuring out how to survive in this new system that was designed to keep them permanently subordinate and economically dependent.

They were building networks that would eventually form the foundation of black communities throughout the South, institutions of mutual support that would survive for generations and eventually provide the organizational basis for civil rights movements decades in the future.

All of this information came to Samuel in pieces over days and weeks delivered through the girl’s brief visits that never lasted more than a few minutes.

A gesture here communicating something about movement or gathering.

A few whispered words there providing crucial context.

Drawings scratched in dirt with a stick and then quickly erased with her foot before anyone could see them and ask questions.

Samuel’s mind assembled it all like a puzzle.

Each piece fitting into a larger picture of the landscape he would have to navigate if he was going to do more than simply survive.

If he was going to actually strike back in some meaningful way against the people who had tried to murder him, he understood with growing clarity that he couldn’t rely on law to deliver anything resembling justice.

The law was written by white men for white men and enforced by white men who had personal and economic stakes in maintaining the racial hierarchy.

The legal system in Georgia had been explicitly designed to maintain white supremacy, and the end of slavery hadn’t fundamentally changed that reality.

If anything, white southerners were doubling down, passing new black codes that gave them legal cover for doing what they had always done, just under different names and with different justifications.

He couldn’t rely on physical force either.

Even if he regained his full strength, even if he armed himself, he was one man against an entire system backed by law enforcement, by social norms, by the threat of mob violence that could be mobilized at any time against any black person who stepped too far out of line.

But Samuel began to understand that he could rely on something else, something more subtle and potentially more powerful than either law or force.

He could rely on guilt and fear and the desperate need of men like Rutherford and Garrett to maintain their self-image as good Christian people who had done nothing wrong.

They went to church every Sunday, sat in the front pews reserved for prominent families, sang hymns with apparent sincerity, nodded seriously during sermons about morality and virtue and Christian duty.

They told themselves and anyone who would listen that they had been kind masters, that they had provided food and shelter and clothing to their slaves, that the war had been about states rights and constitutional principles rather than about slavery.

They were already rewriting history in their own minds, creating narratives where they were victims rather than perpetrators, where the South had been noble and righteous and defeated only by superior northern numbers and industrial capacity.

But underneath all that revisionism and rationalization, there was something else that Samuel could sense, even if he couldn’t articulate it clearly.

There was knowledge they couldn’t quite suppress no matter how hard they tried.

They knew what they had done.