At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters—but then historians noticed their hands

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters, but then historians noticed their hands.

The archive room of the Baltimore Historical Society was unusually quiet on that Tuesday morning in March.

Dr.Rebecca Thompson sat at her desk surrounded by boxes of photographs donated by the estate of a prominent Baltimore family.

The Montgomery collection had been sitting in storage for decades, forgotten until the family’s last heir had passed away and left everything to the historical society.

Rebecca carefully removed each photograph from its protective sleeve, documenting the images and cross- referencing them with the limited information provided.

Most were typical Victorian portraits, stiff formal poses, elaborate clothing, serious expressions frozen in time.

She had processed hundreds of similar collections over her 15 years as the society’s chief archavist.

She was about to break for lunch when she unwrapped a particularly wellpreserved photograph mounted on heavy cardboard.

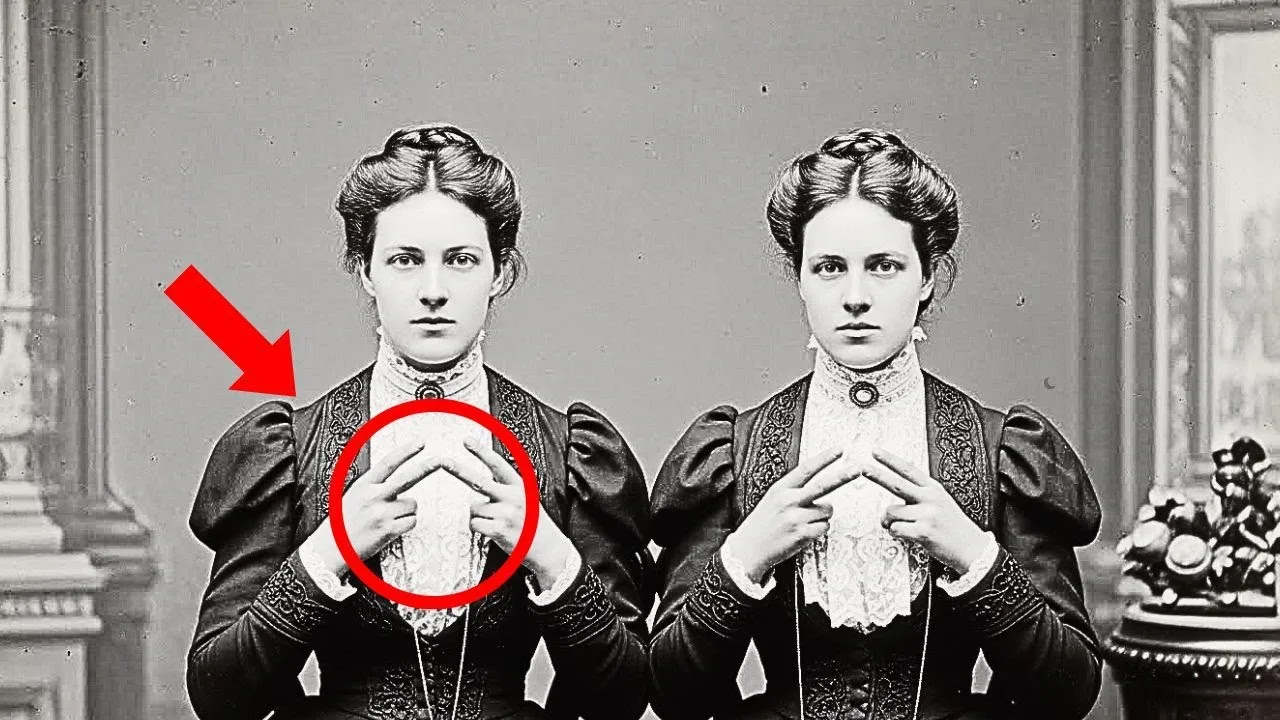

The image showed two young women, probably in their early 20s, seated side by side in an ornate photography studio.

They wore identical dark dresses with high collars and elaborate lace trim, their hair styled in the fashion of the early 1890s.

Both women were smiling, unusual for the era when long exposure times typically required neutral expressions.

The inscription on the back, written in elegant script, read, “Caroline and Elizabeth Montgomery, Baltimore, October 1892.” Rebecca positioned the photograph under her magnifying lamp, admiring the clarity of the image.

The photographer had been skilled.

Every detail was sharp, from the pattern on the wallpaper behind the women to the delicate embroidery on their dresses.

The sisters sat close together, their shoulders nearly touching, conveying warmth and affection.

But as Rebecca’s eyes traveled down to their hands, she paused.

Both women had their hands resting in their laps.

But something about the positioning seemed deliberate, almost staged.

Their fingers were arranged in an identical pattern, thumbs extended, index and middle fingers slightly curved, the other fingers folded.

Rebecca had examined thousands of Victorian photographs, and hand positioning was always carefully considered by photographers.

But this seemed different.

The pose was too specific, too intentional, and too perfectly mirrored between both women.

It didn’t look like a natural resting position or a typical Victorian photographic convention.

She leaned closer, studying the hands more carefully.

The fingers weren’t just positioned identically.

They formed what looked almost like a symbol or sign.

Rebecca felt a tingle of curiosity.

After years of archival work, she had developed an instinct for when something in a photograph deserved closer attention.

This was one of those moments.

She photographed the image with her highresolution camera, zooming in specifically on the hands, and made a note to research Victorian hand gestures and photographic conventions.

There was something here, something hidden in plain sight.

For over 130 years, Rebecca spent her lunch break at her desk, unable to tear herself away from the Montgomery photograph.

She pulled up digital databases of Victorian photography, searching for similar hand positions and other portraits from the 1890s.

After reviewing dozens of images, she confirmed what her instinct had told her.

The hand position in the Montgomery photograph was highly unusual, if not unique.

Victorian portrait photography had conventions for everything.

Where subjects should look, how they should sit, how hands should be positioned.

Hands were typically folded simply resting on laps or arms of chairs or holding props like books or flowers.

But the specific finger arrangement in this photograph didn’t match any standard pose she could find.

Rebecca decided to consult Dr.

Patricia Chen, a colleague who specialized in 19th century social history and non-verbal communication.

She emailed Patricia the highresolution images of the hands, asking if she recognized the gesture or could provide any context.

Patricia called within an hour, her voice urgent.

Where did you find this photograph? In the Montgomery family collection.

Why? Do you recognize the hand position? Rebecca, I think you found something extraordinary.

Can I come to your office? I need to see the original photograph.

40 minutes later, Patricia arrived slightly out of breath from hurrying across town.

Rebecca laid the photograph on her examination table, and Patricia studied it intently, using a magnifying glass to examine every detail of the hands.

“I’ve only seen this gesture described in written accounts, never in a photograph,” Patricia said quietly.

It’s a distress signal.

Rebecca felt her pulse quicken.

A distress signal? Patricia nodded, pulling out her tablet and showing Rebecca a scanned page from a 19th century women’s journal.

In the 1880s and 1890s, there was a network of women’s protection societies, mostly secret or semi-secret organizations that helped women escape dangerous situations, forced marriages, domestic violence, human trafficking.

They developed coded signals that women could use to indicate they were in danger, even in public settings where they were being watched.

She pointed to a diagram in the journal showing a hand position nearly identical to what the Montgomery sisters were displaying.

This particular signal meant help us or we are in danger.

It was designed to be subtle enough that men wouldn’t recognize it, but clear enough that other women who knew the code would understand immediately.

Rebecca stared at the photograph with new eyes.

The smiling faces of Caroline and Elizabeth Montgomery suddenly seemed forced, their expressions perhaps masking fear rather than conveying happiness.

They were calling for help, she whispered.

and someone might have heard them,” Patricia replied.

“We need to find out what happened to these women after this photograph was taken.

If they used this signal, they were in serious danger.

The question is, did anyone save them?” Rebecca and Patricia spent the rest of the afternoon and the following day reconstructing the Montgomery family history.

The Baltimore City directories and census records painted a picture of a once prominent family that had experienced a dramatic reversal of fortune.

James Montgomery, father of Caroline and Elizabeth, had been a successful shipping merchant in the 1870s and early 1880s.

The family had lived in a large home in the fashionable Mount Vernon neighborhood, employed several servants, and moved in Baltimore’s high society circles.

Caroline had been born in 1870, Elizabeth in 1872.

But in 1887, James’ shipping company had suffered catastrophic losses when three of his vessels were destroyed in a hurricane.

The financial blow had been devastating and subsequent poor investments had only worsened the situation.

By 1890, the family was deeply in debt, facing the loss of their home and social standing.

Rebecca found several newspaper articles from 1891 documenting James Montgomery’s business failures and the family’s declining circumstances.

One society column from June 1891 mentioned that the Montgomery Daughters, once fixtures at Baltimore’s finest social events, have withdrawn from public life, no doubt due to their family’s unfortunate financial reversals.

Then, in the Baltimore Sun from September 1892, just one month before the photograph was taken, Rebecca found an announcement that made her blood run cold.

Mr.

James Montgomery is pleased to announce the forthcoming marriages of his daughters, Miss Caroline Montgomery to Mr.

Richard Thornton of Philadelphia and Miss Elizabeth Montgomery to Mr.

Charles Hartwell of New York.

The ceremonies will take place in November of this year.

Rebecca quickly searched for information about Richard Thornton and Charles Hartwell.

What she found was deeply disturbing.

Richard Thornton was a wealthy industrialist, aged 53 in 1892, more than 30 years older than Caroline.

He had been married twice before.

Both wives had died under circumstances described vaguely in obituaries as sudden illness or tragic accident.

Charles Hartwell was somewhat younger in his early 40s, but his reputation was equally troubling.

Rebecca found several newspaper articles from New York describing legal disputes with former business partners, accusations of fraud, and one particularly concerning item.

A restraining order filed by a woman who claimed Hartwell had threatened her after she refused his advances.

Patricia discovered something even more revealing in the personal papers of a Baltimore Society matron.

A diary entry from October 1892 read, “Saw poor Mrs.

Montgomery at church today.

She could barely meet my eyes.

Everyone knows those marriages are business arrangements.

James has sold his daughters to those dreadful men to settle his debts.

The girls looked like ghosts at the autumn ball.

Caroline actually flinched when Thornon touched her arm.

It’s monstrous, but what can be done? The law gives fathers absolute authority over unmarried daughters.

Rebecca sat back in her chair, the pieces falling into place.

The photograph had been taken in October 1892, just weeks before the scheduled weddings.

It had probably been commissioned by Thornton and Hartwell as a formal portrait of their future brides.

Caroline and Elizabeth would have had no choice but to pose, to smile, to present themselves as willing participants in marriages they had been forced into.

But they had found a way to resist, to signal their desperation.

The question now was whether anyone had seen and understood their plea for help.

Rebecca needed to learn more about the photograph itself, who had taken it, under what circumstances, and whether anyone present might have recognized the distress signal.

The photographers’s mark embossed on the bottom of the photograph read, “Sullivan and Daughters, photography, Baltimore.” A search through city directories revealed that Sullivan and Daughters had been a prominent Baltimore photography studio operating from 1885 to 1903.

The studio had been owned by Thomas Sullivan, who worked with his two daughters, Margaret and Catherine, who served as assistants and also photographed female clients, a common practice in an era when women often preferred female photographers for portrait sittings.

Rebecca found an address for the studio’s former location on Charles Street.

The building still stood, though it now housed a coffee shop on the ground floor and apartments above.

She visited it anyway, hoping the current owners might know something about the building’s history.

The coffee shop manager, a history enthusiast himself, directed Rebecca to a small historical society dedicated to preserving Baltimore’s commercial history.

There, she found archived business records from Sullivan and daughters, including appointment books and some correspondents.

The appointment book for October 1892 showed an entry for October 18th.

Montgomery Sisters formal portrait 2 RPM.

Client Mr.

R.

Thornton prepaid.

Rebecca noted that Thornton had commissioned and paid for the photograph.

Further evidence that this was arranged as part of the marriage agreement.

She continued searching through the records and found something unexpected.

A letter dated October 20th, 1892, just 2 days after the Montgomery portrait session.

The letter was addressed to someone named Mrs.

Blackwell and written in a woman’s hand.

Dear Mrs.

Blackwell, I am writing regarding a matter of utmost urgency.

Two young women came to our studio yesterday for a portrait sitting.

During the session, I observed them displaying the signal you taught me to recognize three years ago.

They are in grave danger, scheduled to be married against their will next month to men of questionable character.

Their names are Caroline and Elizabeth Montgomery.

I have included their address and the names of the men they are being forced to marry.

Please help them if you can.

Time is short.

yours in sisterhood, Margaret Sullivan.

Rebecca’s hands trembled as she held the letter.

Margaret Sullivan, the photographers’s daughter, had recognized the distress signal.

She had known what it meant and had contacted someone who might be able to help.

But who was Mrs.

Blackwell? Patricia, when Rebecca shared the discovery, knew immediately.

Sarah Blackwell, she said she ran one of the most active women’s protection societies in Baltimore.

It operated under the cover of a charitable ladies society, but its real purpose was helping women escape dangerous situations, forced marriages, abusive husbands, trafficking situations.

Most of its work was done secretly because what they did was often technically illegal.

They would hide women, help them travel to other cities, sometimes create new identities for them.

Rebecca felt hope rising.

if Margaret Sullivan had contacted Sarah Blackwell and if the Women’s Protection Society had intervened and perhaps Caroline and Elizabeth had been saved.

But she needed to find proof.

Finding records of the Women’s Protection Society proved challenging by design.

Organizations that operated in illegal gray areas helping women defy their fathers or husbands rarely kept detailed records that could be used against them.

But Patricia knew where to look.

The Maryland Women’s Archive has a private collection of Sarah Blackwell’s personal papers.

She explained, “They’re restricted access because they contain sensitive information about women who were helped by the society.

But given the historical importance of this case, I think the archivists will allow us to review the relevant materials.” It took 3 days to obtain permission and schedule access.

Rebecca and Patricia traveled to the archive where they were given access to several boxes of Sarah Blackwell’s correspondents and journals from the 1890s.

Sarah Blackwell had been a remarkable woman.

Widowed young and left with independent means, she had dedicated her life to helping other women escape situations of coercion and abuse.

Her journals documented dozens of cases, women spirited away in the night, new identities created, transportation arranged to distant cities where they could start over.

Rebecca found the entry she was looking for dated in October 21st, 1892.

Received urgent letter from MS regarding two sisters in immediate danger.

The Montgomery case investigated and confirmed father has sold daughters to settle debts.

Marriages scheduled for November 8th.

Both men have troubling histories.

MS report sisters signaled distress during photograph session.

We must act quickly.

Subsequent entries over the following weeks detailed the society’s plan.

They had made contact with a housemmaid in the Montgomery home who was sympathetic to the sister’s plight.

Through her, they had sent coded messages to Caroline and Elizabeth, letting them know help was coming and instructing them to be ready.

The plan was risky.

Caroline and Elizabeth would attend a social function on November 6th, just two days before their scheduled weddings.

During the event, they would excuse themselves to the lady’s retiring room.

Members of the Protection Society would be waiting there with a carriage.

The sisters would leave through a service entrance, and by the time their absence was noticed, they would be miles away.

Sarah’s journal entry for November 7th was brief but triumphant.

The Montgomery sisters are safe.

They left Baltimore last night and are now traveling west under new names.

Their father and the two men are furious, but there is nothing they can do.

The law may give men power over women, but it cannot control women who refuse to be controlled.

C and E are free.

Rebecca felt tears prick her eyes as she read the entry.

The photograph that had captured Caroline and Elizabeth’s silent plea for help had worked.

Someone had seen, someone had understood, and someone had acted.

But what had happened to the sisters after their escape? Had they truly been able to build new lives? Patricia was already searching through their remaining journals.

There’s more, she said, pointing to an entry from 1893.

Sarah continued to monitor the sister’s safety and occasionally received updates from them.

Listen to this.

Sarah Blackwell’s journals provided scattered details about Caroline and Elizabeth’s escape in the early months of their new lives.

The entries were deliberately vague about specific locations, a precaution in case the journals were ever discovered, but they painted a picture of a carefully orchestrated rescue and resettlement.

The November 7th, 1892 entry included more detail than Rebecca had initially noticed.

The sisters departed on the 11 hours train to Pittsburgh, accompanied by Mrs.

Henshaw and Miss Porter, who will escort them to their final destination.

They travel under the names Sarah and Mary Thompson, sisters from Virginia seeking teaching positions in California.

documents have been prepared supporting these identities.

Their father has already been to the police, but we ensured no trail leads to our society or to the sister’s actual whereabouts.

A December entry noted, “Received telegram from Mrs.

Henshaw.

The Thompson sisters arrived safely in San Francisco.

They have secured lodging and will begin seeking employment in the new year.

Both are in good health and spirits, though naturally anxious about their new circumstances.” Throughout 1893, Sarah received occasional letters from Caroline and Elizabeth.

Patricia found several tucked into the journal pages.

The sisters wrote cautiously, never using their real names or revealing too many details, but their gratitude and relief were evident in every line.

One letter from March 1893 read, “Dear Mrs.

Blackwell, we write to thank you once again for the gift of our freedom.

We have found positions as school teachers in a small town near San Francisco.

The work is rewarding and we are building a life we could never have imagined in Baltimore.

We share a small cottage, tend a garden, and each evening we give thanks that we are here together and safe rather than trapped in the nightmare that was planned for us.

The photograph that we risked everything to have taken with our silent plea hidden in plain sight saved our lives.

Please convey our deepest gratitude to Miss Sullivan, whose recognition of our signal set everything in motion.

Rebecca traced the sisters lives through subsequent years, using the coded references in Sarah’s journals, and by searching California records under their assumed names.

Sarah and Mary Thompson, as Caroline and Elizabeth were now known, had indeed become teachers, working in a small school in what appeared to be San Raphael, just north of San Francisco.

The 1900 census showed them living together, both listed as school teachers, unmarried.

By 1910, they had opened their own small private school for girls.

An article from a San Rafael newspaper in 1905 praised the Thompson sisters excellent academy where young ladies receive not only academic instruction but also lessons in independence and self-reliance.

Patricia found something particularly moving in a collection of letters from former students donated to a local historical society.

One letter from 1908 written by a former student mentioned, “Miss Sarah and Miss Mary always told us that education was the key to freedom.

that with knowledge and skills, we could never be trapped or forced into lives we didn’t choose.

They spoke with such conviction that I believe they must have learned this truth from personal experience.

Rebecca realized that Caroline and Elizabeth had transformed their own escape into a mission to help other young women gain the independence and education that could protect them from similar fates.

The school they founded wasn’t just about teaching reading and arithmetic.

It was about empowering girls to control their own destinies.

While Caroline and Elizabeth built new lives in California, Rebecca wanted to understand what had happened to the men they had escaped and the father who had tried to sell them.

The Baltimore newspapers from late 1892 and early 1893 told that part of the story.

The November 9th, 1892 edition of the Baltimore Sun carried a brief item.

Social scandal rocks Baltimore Montgomery daughters vanish on eve of weddings.

The article described the sister’s disappearance from a social function and noted that their father had filed a missing person’s report with the police.

Richard Thornton and Charles Hartwell were quoted expressing shock and concern over the disappearance of their fiances.

But subsequent articles revealed that the men’s concern was more about embarrassment and financial loss than genuine worry for the women’s well-being.

The November 15th article noted that Thornton was demanding James Montgomery repay money that had been advanced as part of the marriage arrangement.

Legal proceedings were threatened.

By December, the scandal had become more sorted.

The Baltimore Evening News published an expose revealing details about the arranged marriages, including the fact that Montgomery had essentially sold his daughters to settle his debts.

Public opinion turned sharply against both the father and the wouldbe grooms.

A society columnist wrote scathingly, “Whatever one thinks of young ladies fleeing their family obligations, one must question the character of men who would enter into such mercenary arrangements that Mr.

Thornton and Mr.

Hartwell sought to purchase brides rather than court them speaks ill of their qualities as gentlemen.

The scandal intensified when a former housemmaid in the Montgomery household gave an interview to a newspaper describing how distressed the sisters had been, how they had pleaded with their father not to force them into the marriages, and how their mother had wept but felt powerless to intervene.

Richard Thornton, facing social censure and business complications from the scandal, left Baltimore for Philadelphia and largely withdrew from public life.

Rebecca found his obituary from 1899.

He had died at age 60, never remarried, his reputation permanently tarnished by the Montgomery affair.

Charles Hartwell fared even worse.

The publicity surrounding the failed marriages prompted other women to come forward with allegations about his behavior.

One woman filed a lawsuit claiming Hartwell had defrauded her in a business dealing.

Another came forward with detailed accounts of his violent temper.

By 1894, Hartwell had left New York and moved west, possibly trying to escape his reputation.

Rebecca found a death notice from 1896 in a Nevada newspaper.

Hartwell had died in a mining accident, though the circumstances were suspicious enough that local authorities had investigated whether it might have been suicide or even murder.

James Montgomery’s fate was perhaps the most pitiable.

After the scandal and the loss of his daughters, his remaining business ventures collapsed.

His wife Helen left him in 1893, moving to live with relatives in Virginia.

James filed for bankruptcy in 1894.

Rebecca found one final newspaper mention of him from 1888, a death notice indicating he had died alone in a boarding house.

His remaining family estranged, his name synonymous with moral failure in Baltimore society.

The photograph that Caroline and Elizabeth had sat for, believing it might be their last hope, had not only saved them, but had also exposed and destroyed the men who had tried to control them.

As Rebecca and Patricia compiled their research into a comprehensive report, they discovered that Caroline and Elizabeth’s story was part of a larger pattern of women’s resistance to coercive marriages in the late 19th century.

Sarah Blackwell’s journals documented dozens of similar cases.

Women who had found ways to signal distress, to reach out for help, to escape situations that the law and society said they had no right to refuse.

The distress signal that the Montgomery sisters had used in their photograph was just one of several coded communications that the Women’s Protection Society and similar organizations had developed.

Patricia found a handbook from 1888 distributed secretly among women’s groups that listed various signals, specific flower arrangements, certain phrases and letters, particular ways of wearing gloves or jewelry, and yes, hand positions and photographs.

The handbook explained, “In situations where a woman is being watched and controlled, where her words are monitored and her movements restricted, she must find ways to communicate that are invisible to her capttors but visible to those who can help.

Learn these signals.

Watch for them.

A woman’s life may depend on your recognition and action.” Rebecca and Patricia decided to create an exhibition at the Baltimore Historical Society documenting not just the Montgomery sisters story, but the broader history of women’s resistance to forced marriages and the secret networks that helped them escape.

The exhibition titled Hidden Signals: Women’s Resistance in Victorian America opened 6 months later.

The centerpiece was the Montgomery photograph displayed with detailed explanations of the hand signal and what it had meant.

Visitors could read Caroline and Elizabeth’s letters, Sarah Blackwell’s journal entries, and Margaret Sullivan’s correspondence.

Interactive displays allowed visitors to learn about other coded signals and the women who had used them.

The exhibition drew unexpected attention from modern advocacy groups working against forced marriage, which remained a problem even in the 21st century.

Representatives from these organizations attended the opening, drawing explicit connections between the historical resistance networks and contemporary efforts to protect women and girls.

One advocate spoke at the opening.

When I see this photograph, I see my clients, women who find creative ways to signal that they need help, even when they’re being watched.

The methods have changed, but the need for vigilance, for recognition, for action, that hasn’t changed at all.

The Baltimore Sun ran a feature article about the exhibition, bringing the Montgomery story to a wide audience.

A descendant of Margaret Sullivan, the photographer who had recognized the distress signal, contacted Rebecca.

The family had kept some of Margaret’s personal papers, including her diary from 1892.

In that diary, Margaret had written extensively about the Montgomery photograph session.

She described how nervous the sisters had seemed, how they had repeatedly positioned their hands in that specific way, and how she had recognized it immediately as the signal Sarah Blackwell had taught her years earlier during a Women’s Protection Society meeting.

Margaret had written, “I knew I had to act quickly but carefully.

The men who commissioned the photograph were waiting in the reception area.

I couldn’t let them see me notice anything unusual, so I completed the session as if nothing was wrong.

developed the plates, delivered the finished photographs, but the moment they left, I wrote to Mrs.

Blackwell.

I only pray I acted in time to help those poor young women.

Rebecca’s research into Caroline and Elizabeth’s later lives revealed that they had lived long, productive years in California, never returning to Baltimore or resuming their original identities.

They ran their school for girls until 1920 when both retired in their late 40s.

Census records and local documents showed them moving to a small farm outside San Raphael where they lived quietly together for another two decades.

They were known in their community as devoted sisters who had dedicated their lives to education and to each other.

Rebecca found obituaries for both women in the San Raphael newspaper.

Elizabeth died first in 1939 at age 67.

Her death attributed to heart failure.

The obituary described her as a beloved retired educator who along with her sister operated the Thompson Academy for many years, educating hundreds of young women and instilling in them the values of independence and self-reliance.

Caroline died just 18 months later in 1941 at age 71.

Her obituary was longer and more detailed, noting that Miss Caroline Thompson never fully recovered from the loss of her beloved sister, Elizabeth, with whom she shared a life of service to young women’s education.

The sisters were inseparable in life, and it seems fitting that they should be reunited so quickly in death.

Both women were buried in the same cemetery, their gravestones simple, but positioned side by side, still together as they had been throughout their lives.

Neither had married, neither had children, but their school had educated more than 300 young women over its 25 years of operation.

And many of those former students had gone on to become teachers, professionals, and advocates for women’s rights themselves.

Patricia discovered letters from former students in various California historical archives.

Many wrote about how the Thompson sisters had changed their lives, giving them confidence and skills that allowed them to make independent choices about their futures.

Several mentioned that the Thompson sisters always seemed to understand what it meant to have your life controlled by others.

And they were determined that we would never experience that.

One particularly moving letter from 1935 written by a former student who had become a social worker read, “When I work with young women in difficult situations, I think of Miss Caroline and Miss Mary and how they believed that every woman deserved the chance to choose her own path.

They never spoke directly about their pasts, but I always sensed that they had escaped something terrible and that their mission to help other young women was born from that experience.

They saved my life by giving me an education and independence.

I can only imagine how many other lives they saved over the years.” Rebecca arranged for the historical society to place a memorial marker at the location of the old Sullivan and Daughters photography studio commemorating both Margaret Sullivan’s recognition of the distress signal and the sisters whose courage in using it had saved their lives.

The marker included a replica of the photograph and an explanation of the hidden signal.

The exhibition remained at the Baltimore Historical Society for a year and then toured to other cities, reaching audiences across the country.

Everywhere it went, visitors stood before the Montgomery photograph, studying the hands, understanding for the first time what had been hidden in plain sight for over a century.

Rebecca gave numerous talks about the research.

And at each one, people shared their own family stories.

Grandmothers who had fled forced marriages, great aunts who had helped other women escape, coded letters, and signals that families had preserved without fully understanding their significance.

One woman in her 80s approached Rebecca after a talk in Washington, DC.

My grandmother was rescued by Sarah Blackwell’s group in 1894, she said quietly.

I always wondered how she had escaped.

Now I understand that there were networks, signals, brave women helping other women.

Thank you for bringing this history to light.

The Maryland Women’s Archive, inspired by the attention the Montgomery case had received, launched a project to digitize and make accessible more records from women’s protection societies throughout the state.

Researchers discovered dozens of similar cases.

Women whose distress had been signaled through coded messages, whose escapes had been orchestrated by secret networks, whose freedom had depended on other women recognizing and responding to their calls for help.

Rebecca and Patricia co-authored an academic article about the Montgomery sisters and the broader phenomenon of coded distress signals in Victorian America.

The article was published in a leading history journal and sparked new research into women’s resistance strategies throughout the 19th century.

But for Rebecca, the most meaningful outcome was simply that Caroline and Elizabeth Montgomery’s story was now known.

The photograph that they had risked everything to embed with their plea for help had finally delivered its full message more than 130 years after it was taken.

The historical society kept the original photograph in its permanent collection, displayed prominently with the caption, “Caroline and Elizabeth Montgomery, October 1892.” This photograph shows two young women displaying a distress signal with their hands, calling for help to escape forced marriages.

Their signal was recognized by photographer Margaret Sullivan, who contacted the Women’s Protection Society.

The sisters were successfully rescued and lived free, productive lives under new identities in California.

Their courage in finding a way to ask for help, and the courage of the women who answered that call reminds us that resistance to injustice takes many forms, and that attentiveness to others suffering can save lives.

Visitors often photographed the image, sharing it on social media with comments about the hidden signal and the bravery of the women involved.

Several modern advocacy groups adopted the hand signal as a symbol of resistance to coercion and control, teaching it as a contemporary distress signal that could be used by women in dangerous situations.

Rebecca sometimes stood quietly in the gallery, watching visitors discover the story.

She saw them lean in to examine the hands, saw their expressions change as they understood what they were seeing, saw them read the accompanying text with growing emotion.

The photograph that had appeared to be simply a portrait of two sisters had become a window into a hidden history of courage, resistance, and the networks of women who had refused to let other women face danger alone.

The Montgomery sisters had found a way to speak across more than a century.

Their message finally heard and understood.

Their hands positioned so carefully in that Baltimore photography studio in October 1892 had reached across time to tell a story of terror-faced help sought freedom gained and lives reclaimed.

And in telling their story, Rebecca had helped ensure that the countless other women who had resisted, who had signaled who had escaped, would not be forgotten either.

The photograph remained a testament to the power of small acts of courage and the importance of paying attention to what others might be trying to tell us, even when their voices are silenced and only their hands can

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load