The ledger lay open on Dr.Elias Thorne’s desk, its pages brittle and foxed with age, a testament to years of

meticulous, almost obsessive recordkeeping.

Outside his window, the

Alabama sun, a relentless orb of fire beat down on the dusty main street of

Willow Creek.

The year was 1847, and the air hung thick and heavy, laden with the

scent of blooming jasmine, the distant hum of cicas, and the everpresent cloying sweetness of ripening cotton.

But Thorne, a man whose world was usually confined to the tangible and the empirical, was lost in a pattern that

defied easy explanation, a chilling anomaly that had begun to consume his every waking thought.

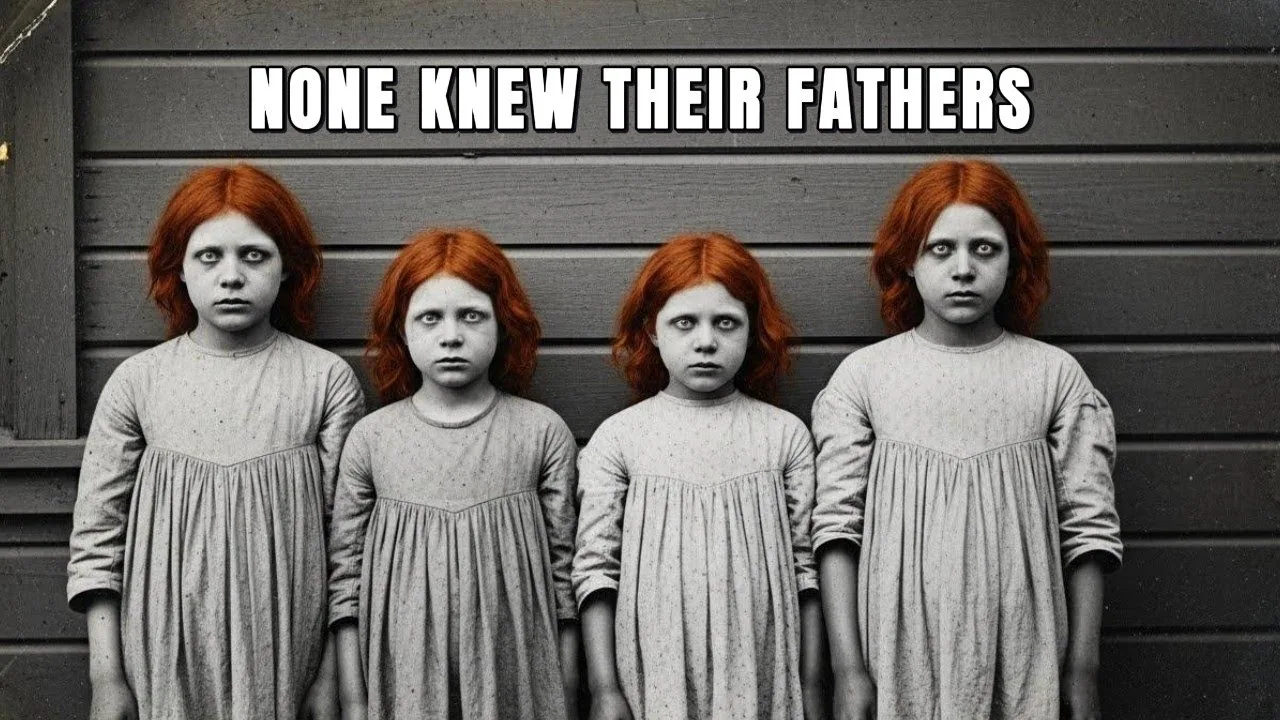

17 girls, all born

with hair the color of a sunset blaze, a fiery, unmistakable red, all with skin

so pale it seemed to drink the light, almost translucent against the deep, rich tones of their mothers.

And not one

of them, not a single one, had a known father.

The first instance had been a

curiosity, a genetic quirk, the second a strange coincidence.

But by the 17th,

spread across six different plantations, the pattern had solidified into something far more sinister, a silent

accusation etched into the very fabric of the community.

Thorne, a physician

trained to heal and to observe, found himself entangled in a mystery that whispered of systemic cruelty, of power

wielded without conscience, and of a collective silence so profound it was deafening.

He saw the children.

He saw

their mothers.

And he saw the unspoken truth that everyone else seemed determined to ignore.

The question that

gnored at his soul that kept him pacing his small office long after the town had

settled into its uneasy slumber, was not how this was happening, but why an

entire society would choose to look away.

Before we continue with the story

of Dr.

Thorne and the unsettling secret that would define his final years in Willow Creek, I want to take a moment to

thank you for joining us here at Liturgy of Fear.

If you find yourself drawn to these forgotten corners of history,

these narratives that whisper uncomfortable truths from the past, please consider subscribing to our

channel and hitting that notification bell.

The algorithms often overlook stories like these.

Stories that

challenge our perceptions and force us to confront the darker aspects of human history.

Your support is invaluable in

ensuring we can continue to bring these hidden histories to light.

Now, let us

return to the stifling heat of that Alabama summer, to the quiet desperation of Willow Creek, and to the moment when

Doctor Thorne first began to understand the true horrifying scope of what he was

witnessing.

Willow Creek, established in the early 1820s, was less a town of

grand aspirations and more a functional artery in the vast beating heart of the

Cotton Kingdom.

Its main street, a perpetually dusty ribbon of packed

earth, was flanked by buildings that prioritized utility over aesthetics.

A

general store, its wooden porch groaning under the weight of barrels and crates.

A sturdy brick bank symbol of the wealth flowing from the fields, a modest courthouse where justice, or at least

its local interpretation, was dispensed.

a clapboard church whose steeple was the tallest structure for miles, and the

inevitable saloon, its rockous laughter and piano music spilling out into the humid evenings.

Dr.

Elias Thorne’s

office, a small, unassuming structure tucked between the dry goods store and the blacksmith, blended seamlessly into

this landscape of practical necessity.

Thorne had arrived in 1842, a young man

in his late 20s, fresh from his medical studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

He’d envisioned a life of

intellectual pursuit, perhaps even contributing to the burgeoning fields of medical science.

Instead, the South had

offered him a stark reality, a practice dominated by the brutal exigencies of plantation life.

His days were a

relentless cycle of treating sunstroke, fever, dissentry, and the myriad injuries inflicted by the unforgiving

labor of cotton cultivation.

He set broken bones, lanced boils, and most

frequently attended to the births of children, both free and enslaved.

The

white families, the planters and their kin, viewed him with a mixture of respect and condescension, preferring

their own remedies for minor ailments and calling upon him only when death seemed imminent.

The enslaved population, however, saw him as a necessary, if sometimes feared,

presence, a man who could alleviate suffering even if he could not change their circumstances.

He was a man of

quiet habits, Thorne, with a lean frame that seemed perpetually stooped over his medical texts or his ledger.

His

spectacles perched precariously on his aqualine nose were often smudged, and his thinning brown hair was perpetually

disheveled from nervous habit.

He was a bachelor, his life devoid of the domestic comforts that many of his peers

enjoyed.

His true companions were his books, his meticulous notes, and the

everpresent unspoken questions that simmerred beneath his calm exterior.

He

was, above all, an observer, a man who believed in the power of data, of patterns, of the cold, hard facts that

could be gleaned from careful documentation.

It was this very dedication to observation that had led

him down this unsettling path.

The first entry that would later haunt him was made in the spring of 1844.

He’d been summoned to the Bowmont Plantation, one of the largest and most prosperous estates in the county owned

by the formidable Augustus Bowmont.

The call had come in the dead of night, a

frantic rider on a lthered horse, signaling a difficult birth.

The mother, a young enslaved woman named Claraara,

couldn’t have been more than 18.

She’d been in labor for nearly a day, her cries muffled by the thick walls of the

small windowless cabin she shared with her family.

Thorne had worked tirelessly, his brow beaded with sweat

in the oppressive heat, guiding the birth with practiced hands.

When the infant finally emerged, a tiny squalling

bundle, Thorne had performed his routine examination.

He checked for 10 fingers,

10 toes, listened to the strong beat of her tiny heart, and cleared her lungs.

A

healthy girl by all accounts.

But as he’d wiped away the verex, his fingers had brushed against a shock of hair.

It

was an unmistakable shade of copper, vibrant and fiery, even in the flickering lamplight, and her skin, once

cleaned, was remarkably pale, almost translucent, revealing the delicate network of veins beneath.

He’d glanced at Claraara, whose skin was the color of rich earth, and then at the other women in the cabin, their faces

etched with concern, their complexions uniformly dark.

Red hair, Thorne knew

from his medical texts, was a rare genetic variation that could appear in any population.

But this combination,

the intense red, the extreme power, was striking.

A beautiful girl, Claraara,” he’d said, his voice softer than usual as he wrapped the infant in a clean cloth and

gently placed her in her mother’s trembling arms.

Strong and healthy, Claraara had looked down at her

daughter, her face a complex tapestry of exhaustion, relief, and something else Thorne couldn’t quite decipher.

A

flicker of fear perhaps, or a deep, weary resignation.

Thank you, doctor,” she’d whispered, her

voicearo, her eyes never leaving the tiny face nestled against her breast.

Thorne had lingered, as was his custom,

ensuring both mother and child were stable.

As he’d packed his instruments, the question, almost an afterthought,

had slipped out.

The father, is he here on the plantation? The air in the cabin

had grown heavy, thick with unspoken tension.

The other women, who had been murmuring softly, fell silent.

their

gazes dropping to the rough huneed floorboards.

Claraara had simply shaken her head, her eyes still fixed on her

daughter.

“Don’t know, sir,” she’d murmured, her voice barely audible.

“Don’t rightly know.” It was an answer

Thorne had heard countless times.

In the brutal calculus of slavery, the paternity of enslaved children was often

deliberately obscured, especially when a white man was involved.

To acknowledge

such a union was to invite complications, to challenge the carefully constructed fictions of racial

purity and ownership.

The children, regardless of their parentage, were simply absorbed into the

enslaved population.

Their mixed heritage and open secret that was never openly acknowledged.

Thorne, accustomed

to the unspoken rules of this society, had accepted the answer without pressing further.

He’d made a brief entry in his

ledger.

female infant, healthy, unusual coloring.

It was a curiosity, nothing more.

But then, eight months later, another call

had come.

This time, from the Oak Haven plantation, a smaller, less prosperous

estate owned by the struggling Oak Haven family.

The mother, a woman named Bess,

had gone into premature labor.

Thorne had arrived to find a desperate situation, and despite his best efforts,

the infant, another girl, had been weak and sickly.

She’d lived only 3 days.

But

in those three days, Thorne had noted the same distinctive features.

Bright,

fiery red hair and pale, almost translucent skin.

He’d asked Bess the

same question and received the same weary, resigned answer.

Don’t know, sir.

two red-haired girls born months apart on different plantations to different

mothers.

It was unusual, certainly, but Thorne, ever the rationalist, had still

sought a scientific explanation, perhaps a rare genetic trait, a distant

common ancestor whose genes had resurfaced.

He’d consulted his medical texts,

searching for precedents, for explanations.

But then there had been a third and a

fourth.

And by the summer of 1847, when Thorne sat at his desk, the ledger

opened before him.

The number had climbed to 17.

17 girls, all with the

same distinctive red hair and pale skin.

17 girls born to enslaved women across

six different plantations.

17 girls whose fathers were unknown or

at least unagnowledged.

The statistical improbability was staggering.

Thorne had

spent countless hours pouring over his records, cross-referencing dates, locations, and the physical

characteristics of the children.

He’d ruled out environmental factors, genetic mutations within the enslaved

population, as the mothers showed no such traits and any other plausible scientific explanation.

The only

conclusion that remained, the only one that fit the undeniable evidence, was one that Thorne had initially resisted

with every fiber of his being.

These children all shared a father, a white

father, a father with distinctive red hair who had access to multiple plantations and the power to ensure that

his actions would never be questioned, never challenged, never even whispered

about.

The realization had settled upon thorns slowly like a suffocating shroud.

It was

not a sudden epiphany, but a creeping dread, a cold certainty that seeped into his bones.

He had uncovered a terrible truth, a systematic pattern of abuse that had been unfolding for years, right under

the noses of an entire community.

And now the impossible question, what should

he do about it? The town of Willow Creek, like so many others in the antibbellum south, operated on a

delicate yet brutally enforced social contract.

It was a world built on rigid

hierarchies, where power flowed downwards from white men of property and wealth.

At the bottom of this pyramid

were the enslaved who possessed no legal rights, no voice, no protection.

The law

itself was a tool designed to maintain this structure, to protect the interests

of the powerful and to crush any challenge to their authority.

An enslaved woman who accused a white man

of rape would not only be disbelieved, but would likely face severe punishment for daring to speak against a white man.

The very concept of rape in such a context was legally meaningless.

Enslaved people were property, and a man could not be accused of a crime for using his own property or for

trespassing on another man’s property with that man’s tacit permission.

The children born of such unions were simply

more property, more assets to be worked or sold as their owners saw fit.

Their

existence was a testament to the absolute power of the white man, a power that extended even to the bodies of

enslaved women.

Even if Thorne could somehow bring charges against the perpetrator, and he had no legal

standing to do so, the case would be heard by a judge who was likely a friend or business associate of the accused,

and decided by a jury of white men who had every incentive to protect one of their own.

An accusation of this nature

would be seen as a betrayal of racial solidarity, a dangerous precedent that

could undermine the entire system.

The consequences for the women involved

would be dire.

To draw attention to their children’s paternity would be to mark them as troublemakers, as threats

to the social order.

They would be punished, sold away, separated from

their children and families.

The very act of trying to help them would likely make their situations worse.

Thorne

understood all of this.

He was not a naive man.

He had lived in the south long enough to understand how power

worked, how the system protected itself with an iron fist cloaked in velvet.

But

understanding did not make the knowledge any easier to bear.

It festered within him a toxic brew of anger, frustration,

and helplessness.

He found himself lying awake at night, staring at the ceiling of his small bedroom.

the sounds of the

night, the chirping crickets, the distant baying of a hound, doing little to soothe his agitated mind.

He imagined

confronting the man directly, demanding an explanation, threatening to expose him.

But to what end? The man would deny

everything, and Thorne would be ruined, his practice destroyed, his reputation

shattered.

He imagined writing to authorities in Montgomery, laying out his evidence in careful detail.

But he knew such a letter would be ignored or worse traced back to him with dire consequences.

He even considered more drastic measures.

He was a doctor after all.

He

had access to medicines, to poisons.

It would be easy enough to slip something into the man’s drink at a social

gathering to make it look like a heart attack or a sudden illness.

But Thorne

was not a murderer.

The thought of taking a life, even the life of a man he

had come to despise, was abhorrent to him.

And so he did nothing.

He continued

his rounds, delivered babies, treated illnesses, and kept his terrible knowledge locked away in his heart, and

in the coded entries of his ledger.

But the weight of that knowledge was crushing him slowly, inexurably.

The

question of who had become an obsession for Thorne.

He began to pay attention to details he had previously overlooked.

At

church on Sundays, he would surreptitiously scan the congregation, noting the color of every man’s hair.

At

social gatherings, he would listen intently to conversations, trying to discern who had business dealings with

multiple plantations, who traveled frequently, who had the kind of access that would allow for such systematic

abuse.

The pool of suspects was surprisingly small.

Willow Creek was not

a large town, and the white population was even smaller.

Most of the men were tied to specific

plantations, rarely venturing beyond their own property lines except for trips to town or occasional social

calls.

But there were a few men whose work required them to move freely between

plantations.

the cotton broker who negotiated sales and arranged shipments, the itinerant preacher who held services

at various plantation chapels, the traveling salesman who brought goods from Mobile and Montgomery, and the

county sheriff who made his rounds enforcing what passed for law in this corner of Alabama.

Thorne began to

observe these men more carefully.

The preacher, Reverend Josiah Blackwell, was

a thin aesthetic man with dark hair going gray at the temples.

The salesman,

a jovial fellow named Cornelius Briggs, was nearly bald, what little hair he had

left being a mousy brown.

The sheriff, Wade Hutchkins, had black hair and a

thick black beard, that left the cotton broker, Alistister Finch.

Finch was a

man of considerable presence, a force of nature in the quiet town of Willow Creek.

Tall and broad shouldered with a

booming voice that carried across a room and a laugh that seemed to shake the very rafters of the saloon.

He was a

fixture at every social gathering, every church service, every important meeting.

He had built his business from nothing, arriving in Willow Creek in the late 1830s with little more than a sharp

mind, an uncanny knack for numbers, and a talent for negotiation.

Within a

decade, he had become indispensable to the local economy.

The man who could get the best prices for cotton, who had

connections in Mobile and New Orleans, who could arrange credit when times were tight.

He was a man of influence, a man

of means, a man whose word carried weight.

And Alistair Finch had hair the

color of burnished copper, a vivid, unmistakable red that he wore like a crown, often swept back from his high

forehead.

The first time the connection occurred to Thorne, he had been standing in Finch’s opulent office, discussing

payment for medical services rendered to one of Finch’s household servants.

Finch

had been seated behind his massive mahogany desk, the afternoon sun streaming through the tall window behind

him, setting his hair ablaze with light.

Thorne had been in the middle of a sentence, explaining a dosage, when the

thought struck him with such force that he had actually stumbled over his words.

his voice trailing off into an

embarrassed cough.

The hair, the same shade, the exact same shade as the

children.

Finch had looked at him quizzically, a slight smile playing on his lips.

“Are you quite well, doctor?

You look as though you’ve seen a ghost.” Thorne had recovered quickly, mumbling something about the oppressive heat, and

had finished his business as quickly as possible.

But as he had walked back to his office, the image of Finch’s fiery

hair, illuminated by the sun, had burned itself into his mind.

Could it be? Could

Alistister Finch, respected businessman, church elder, pillar of the community,

be the father of 17 enslaved children? The more Thorne thought about it, the

more the pieces seemed to fall into place with a horrifying precision.

Finch’s business required him to visit

every major plantation in the county, often staying overnight when negotiations ran late or when social

obligations dictated.

He was a bachelor, living alone in a large, well-appointed

house on the edge of town with only a small staff of enslaved servants.

He was

charming, persuasive, the kind of man who could talk his way into or out of any situation.

and he was powerful with

connections that reached all the way to the state capital in Montgomery.

If any man in Willow Creek could commit such

acts with complete impunity, it would be Alistair Finch.

But suspicion was not

proof.

Thorne was a man of science, trained to rely on evidence and observation, not speculation and

conjecture.

He needed to be certain.

And so he began to investigate as discreetly

as possible, weaving his inquiries into his daily rounds, his conversations, his

very observations of the world around him.

He started by reviewing his ledger

even more carefully, noting not just the dates of the births, but also the approximate dates of conception, working

backward from the gestational period.

Then during his visits to the various plantations, he began to ask subtle,

seemingly innocuous questions.

Had Mr.

Finch been by recently? When had he last

visited? How long had he stayed? Had he dined with the family? Had he spent the

night? The answers, pieced together over weeks and months, formed a damning pattern.

In almost every case,

Alistister Finch had visited the plantation in question approximately 9 months before the birth of a red-haired

child.

Sometimes his visits had been for business, negotiating cotton prices,

arranging shipments.

Sometimes they had been social, dinner with the plantation

owner, a game of cards, a night of drinking and conversation in the parlor.

But he had been there every single time.

The evidence was circumstantial, yes,

but it was overwhelming.

Thorne felt a cold certainty settling in his chest, a

weight that made it hard to breathe, a knot of dread that tightened with each new confirmation.

He had uncovered a

terrible truth, a systematic pattern of abuse that had been going on for years, right under the noses of the entire

community.

And now he faced an impossible question.

What should he do about it? The answer he knew was fraught

with peril, not just for himself, but for the very women and children he sought to protect.

The weight of his

knowledge began to press down on Thorne, suffocating him.

He found himself increasingly withdrawn, his usual quiet

demeanor deepening into a brooding silence.

The vibrant Alabama landscape,

once a source of quiet contemplation, now seemed to mock him with its beauty, a stark contrast to the ugliness he

carried within.

One sweltering afternoon, as he rode his buggy along a dusty track bordered by towering pines,

the sun beating down relentlessly, Thorne found himself contemplating the sheer audacity of Finch.

How could a man live with such a secret, such a trail of silent victims? Did he

feel no guilt, no shame? Or had he, like so many others in this society, simply

compartmentalized his actions, viewing the enslaved as property, their bodies and lives existing solely for his

gratification and profit.

He pulled the buggy to the side of the road, the horses stamping impatiently in the heat.

He reached into his medical bag, not for an instrument, but for a small flask of whiskey he had begun to carry with

increasing frequency.

A long swallow burned its way down his throat, offering

a fleeting moment of oblivion before the thoughts rushed back, more insistent

than ever.

He thought of Claraara, the first mother, her face a mask of weary

resignation.

He thought of Bess, whose child had died after only 3 days, a tiny red-haired

ghost.

He thought of the other mothers, their names now etched into his memory.

Sarah, Eliza, Martha, Lucy.

Each one a silent testament to Finch’s depravity.

Each one a victim of a system that offered no protection.

Thorne knew he couldn’t speak out without proof.

And

even with proof, the system would protect Finch.

He was trapped, a silent witness to a crime that society refused

to acknowledge.

The injustice of it all was a bitter pill, one he swallowed

daily.

The autumn of 1848 brought with it the annual harvest celebration at the

Bowmont plantation.

It was a grand affair, a ritual of wealth and power,

where Augustus Bowmont, the patriarch of the estate, invited the white families

of the county to revel in the bounty of another successful cotton harvest.

The air was filled with the aroma of roasted

meats, sweet pies, and expensive tobacco.

Music provided by a small

ensemble of enslaved musicians, drifted from the wide veranda of the plantation

house, mingling with the laughter and animated chatter of the guests.

Thorne had little taste for such gatherings,

finding the forced conviviiality and superficial pleasantries grating, but attendance was expected, a social

obligation he couldn’t easily avoid without drawing undue attention.

He stood on the periphery of the

festivities, a glass of lukewarm punch in his hand, trying to appear engaged,

his gaze sweeping over the scene with his usual detached observation.

Alistister Finch was there, of course,

respplendant in a new suit of fine linen, his red hair gleaming like a beacon in the flickering light of the

torches that had been strategically placed around the ver.

He was, as always, the center of attention, holding

court with a group of planters, regailing them with some humorous anecdote about a recent trip to Mobile.

His booming laugh echoed across the gathering, and the other men laughed along with him, slapping him on the

back, raising their glasses in toast to his wit and prosperity.

Thorne watched

him with a mixture of disgust and morbid fascination.

How did he do it? How did

he move through the world with such ease, such confidence, knowing what he had done, what he continued to do? Did

he feel no pang of conscience, no flicker of shame? Or had he truly convinced himself that his actions were

justified, that enslaved women were fair game, that the children he fathered were

simply an unfortunate yet ultimately inconsequential byproduct of his

desires? As Thorne watched, a young enslaved girl, perhaps seven or eight

years old, approached the group of men carrying a silver tray laden with fresh drinks.

She was one of the house

servants, dressed in a clean but simple cotton dress, her hair neatly tied back

with a ribbon, and her hair was red, bright, vivid, unmistakable red.

Thorne

recognized her immediately.

She was Claraara’s daughter, the first of the red-haired children he had delivered.

She had grown into a bright, curious child, and Thorne had seen her on

several occasions during his visits to the Bowmont plantation.

The girl offered the tray to the men,

her eyes downcast, as she had been trained to do.

The planters took their

drinks without truly looking at her, their conversation barely pausing.

But Finch paused.

He looked at the girl,

really looked at her, and for a brief, almost imperceptible moment.

Something

flickered across his face.

Recognition, a fleeting shadow of something unreadable.

Thorne couldn’t be sure.

Then Finch smiled, a warm, almost paternal smile, and reached out to pat

the girl gently on the head, his large hand ruffling her fiery red hair.

Thank you, child,” he said, his voice surprisingly gentle.

“You’re doing a fine job.” The girl bobbed a quick

curtsy and hurried away, her small frame disappearing into the shadows.

Finch

turned back to his companions, the moment already forgotten, resuming his anecdote as if nothing had happened.

But

Thorne had seen it.

That brief touch, that fleeting smile, it was a gesture of

ownership, of casual acknowledgement.

Finch knew.

He knew the girl was his

daughter, and he didn’t care.

Or rather, he cared so little that he could acknowledge her in public in front of

dozens of witnesses, secure in the knowledge that no one would say a word.

The sheer brazeness of it, the absolute

impunity, was breathtaking.

The realization hit Thorne like a physical blow, a punch to the gut, that left him

breathless.

It wasn’t just that Finch was committing these acts.

It was that he was doing so openly, brazenly,

confident in his absolute immunity.

The entire community knew, or at least suspected, and they were all complicit

in the silence.

The planters who employed Finch’s services, the wives who

smiled and nodded at social gatherings, the sheriff who enforced the law, the preacher who delivered sermons on

morality.

They all knew, and they all chose to look away.

Their silence was a

shield protecting Finch and by extension the fragile edifice of their own

society.

Thorne felt a wave of nausea wash over him.

He set down his glass of

punch, the clinking sound barely audible above the den, and made his way to the

edge of the verander, kneading air, needing to escape the suffocating atmosphere of the celebration.

He stood

in the darkness beyond the torch light, breathing deeply, trying to calm the frantic pounding of his heart.

The sweet

scent of jasmine now seemed cloying, sickly.

Dr.

Thorne, are you unwell? He

turned, startled to find Aara, the elderly enslaved woman who served as a midwife on the Bowmont plantation,

standing a few feet away.

She had been watching him, her dark eyes, ancient and

wise, filled with a quiet concern.

Ara was a woman of perhaps 60 years, her

face a road map of lines etched by age and hardship, her hair a silver halo

beneath her headscarf.

She had assisted Thorne at dozens of births over the years, and he had come to respect her

knowledge and skill.

She knew more about childbirth than most trained physicians.

Her expertise born of decades of

practical experience and an intuitive understanding of the human body.

“I’m fine, Ara,” he said, though his voice

sounded strained even to his own ears.

“Just needed some air.” Ara nodded slowly, her gaze unwavering.

“You’ve

been troubled lately, doctor,” she said quietly, her voice a low, resonant

murmur.

“I seen it in your face.

You carry in something heavy.

Thorne hesitated.

He had never spoken openly

about his suspicions.

Not to anyone.

But Lara was different.

She was part of the

enslaved community, privy to their secrets and their suffering, a silent guardian of their unspoken truths.

If

anyone would understand, it would be her.

If anyone could offer a glimmer of

insight, it was Ara.

Ara, he began slowly, choosing his words

with immense care.

The children, the ones with red hair.

You’ve helped

deliver several of them, haven’t you? Aar’s expression didn’t change, but

something shifted in her eyes, a subtle flicker of weariness, a deepseated caution born of a lifetime of survival.

Yes, sir, I have.

Her voice was flat, devoid of emotion.

Do you? Thorne paused, struggling to articulate the unutterable.

Do you know who their father is? For a long moment, Ara said nothing.

She

looked past Thorne toward the brightly lit veranda, where the celebration continued, where Alistister Finch’s

booming laugh could still be heard above the music and conversation.

The sounds of revalry seemed to mock their quiet,

desperate exchange.

Some things, doctor, she said finely, her voice barely above

a whisper, are better left unspoken.

For the sake of the mothers, for the sake of

the children.

Speaking the truth don’t always set you free.

Sometimes it just gets you sold down the river.

Or worse.

But it’s wrong, Thorne said, his voice tight with a raw, barely suppressed frustration.

What he’s doing, it’s

wrong.

Someone should should what? Allah interrupted her voice, though still

quiet, now sharp, with an edge of weary anger.

Should speak up, should accuse a

powerful white man.

And what you think would happen then, doctor? You think

there’d be justice? You think those women and children would be protected?

She shook her head slowly, a gesture of profound resignation.

No, sir.

All that

would happen is suffering.

More suffering.

The mothers would be punished.

The children would be sold

away, scattered like dust in the wind.

And Mr.

Finch, he’d go right on with his

life.

Same as always.

That’s how this world works, doctor.

You know that as well as I do.

Thorne felt the truth of

her words like a knife in his chest, twisting deep.

She was right.

Of course,

she was right.

The system was designed to protect men like Finch and to punish anyone who dared to challenge them.

speaking out would accomplish nothing except to cause more pain for those who were already suffering beyond measure.

His idealism, his scientific belief in truth and justice, crumbled under the weight of her stark realism.

“So we just

do nothing?” he asked, his voice hollow, devoid of hope.

“We just let it

continue.” Ara’s expression softened slightly, a flicker of compassion in her

ancient eyes.

“We survive, doctor.

That’s what we do.

We protect our own as

best we can.

We love those children, red hair and all.

And we raise them up

strong.

We teach them what we can.

And we remember.

We remember everything.

Maybe someday things will be different.

Maybe someday there’ll be a reckoning.

But that day ain’t today, and it ain’t

going to be tomorrow neither.

She turned to go, then paused and looked back at him, her gaze piercing.

You a good man,

Dr.

Thorne.

You got a kind heart.

But kindness ain’t always enough in this

world.

Sometimes the best thing you can do is bear witness.

Remember what you seen.

Write it down.

Maybe someday

someone will want to know the truth.

And then your words, they might mean

something.

And with that, she disappeared back into the shadows, leaving Thorne alone with his thoughts,

his terrible, useless knowledge, and the suffocating realization that the silence was not just a choice, but a brutal

necessity for survival.

The years that followed were a slow, agonizing torture for Thorne.

He

continued his practice, continued his rounds, continued to deliver the red-haired children that appeared with

disturbing regularity.

By 1852, the number had grown to 23.

23 girls

scattered across the county, all bearing the unmistakable mark of their father.

Each birth was a fresh wound, a new entry in his ledger, a further testament

to his own impotence.

He watched them grow, these children.

Some were bright and spirited, full of life despite the

circumstances of their birth.

Their fiery hair a defiant crown.

Others were

quiet and withdrawn, as if they sensed the weight of the secret they carried, the unspoken questions that hung in the

air around them.

All of them were treated differently, set apart by their unusual appearance.

Some in the enslaved

community embraced them, protecting them, as had said, weaving them into the intricate tapestry of their families.

Others kept their distance as if the children’s very existence was a dangerous reminder of the power dynamics

that governed their lives, a visible scar on the face of their community.

Thorne also watched Alistister Finch,

though he tried to be subtle about it, his observations becoming almost a morbid ritual.

Finch continued to

prosper, his business growing, his influence expanding.

He had been elected to the town council,

appointed as an elder in the church, his voice carrying significant weight in both secular and spiritual matters.

He

donated generously to local causes, funded the construction of a new schoolhouse, sponsored Fourth of July

celebrations with lavish fireworks displays.

He was, by all accounts, a

model citizen, a man of virtue and integrity, a pillar of the community.

The hypocrisy of it all made Thorne physically ill, a constant knot of nausea in his stomach.

He began to drink

more than he should, seeking a fleeting solace in whiskey.

When the weight of his knowledge became too much to bear,

his practice suffered.

He became forgetful, distracted, prone to dark

moods that alienated his few acquaintances.

People began to whisper that Doctor Thorne was not quite right,

that perhaps the strain of his work, the constant exposure to suffering and death, had affected his mind.

He heard

the whispers, but he no longer cared.

What was a reputation, after all, in the face of such profound injustice? In the

spring of 1854, a new red-haired girl was born on the McIntyre plantation.

The

mother, a young woman named Hannah, had a difficult labor, and Thorne was called

in the middle of the night.

He arrived to find Hannah in distress, the birth not progressing as it should, her

strength ebbing away with each agonizing contraction.

He worked for hours, using

all his skill and knowledge, his hands slick with sweat and blood.

But in the

end, both mother and child died.

The tiny infant, stillborn, had a shock

of bright red hair.

Thorne was devastated.

He had lost patience before.

It was an inevitable, brutal part of medicine, especially in such primitive conditions.

But this death felt

different.

It felt like a judgment, a condemnation of his own inaction.

Hannah

had died bringing one of Finch’s children into the world, and Thorne had done nothing to stop it, nothing to

protect her.

He had merely borne witness, and it felt utterly, horribly insufficient.

He attended the burial, a

simple, somber affair in the plantation’s slave cemetery.

The other enslaved people gathered around the

shallow grave, their voices low and mournful as they sang spirituals that spoke of sorrow and hope.

Thorns stood

at the edge of the group, his hat in his hands, tears streaming down his face, unashamed.

The raw grief he felt was not

just for Hannah and her child, but for all the silent victims, for the crushing weight of the system, and for his own

profound helplessness.

After the burial, a cold, hard resolve

settled within him.

He went directly to Finch’s office.

He didn’t have a plan,

didn’t know what he was going to say.

He just knew he couldn’t remain silent any longer.

The despair had reached its

zenith, and in its place a desperate, reckless courage had bloomed.

He found Finch at his desk, reviewing ledgers, a

quill pen scratching softly across the paper.

Finch looked up as Thorne entered, a welcoming smile on his face,

a practiced mask of geneiality.

Dr.

Thorne, what a pleasant surprise.

To

what do I owe the He paused, his smile faltering as he took in Thorne’s

disheveled appearance.

The wildness in his eyes, the raw grief etched on his face.

“Are you quite well, doctor?”

“Hannah died last night,” Thorne said, his voice flat, devoid of inflection,

yet carrying an immense weight.

On the McIntyre plantation, she and her child,

Finch’s expression shifted to one of practiced concern.

“How tragic! I’m very

sorry to hear that.

Was there a complication?” The child,” Thorne continued as if Finch hadn’t spoken, his

gaze fixed on Finch’s fiery red hair.

“Had red hair, just like all the

others.” The room went very quiet.

The only sound was the distant clatter of a

wagon on the street outside.

Finch’s expression didn’t change, but something

hardened in his eyes, a subtle tightening around the mouth.

The genial

mask slipped, revealing a glimpse of something cold and calculating beneath.

“I’m not sure I understand what you’re implying, doctor.” Finch’s voice was

calm, almost dangerously so.

“I think you do,” Thorne said, his voice shaking

now, not with fear, but with a righteous, long suppressed anger.

“I’ve been keeping records.

24 children in 10

years, all with red hair, all born to enslaved women on plantations you visit

regularly, all with fathers who are conveniently unknown.

Finch leaned back in his chair, his fingers steepled

beneath his chin, his eyes narrowed.

When he spoke, his voice was still calm,

almost amused, a chilling display of control.

That’s quite an accusation, Dr.

Thorne.

Based on what? The color of some children’s hair? Genetics is a mysterious thing.

Surely you, as a man

of science, understand that.

A rare trait, perhaps passed down through generations.

You’re seeing patterns

where none exist, doctor.

I understand, Thorne said, his voice rising, trembling

with the force of his long-held fury, that you’ve been raping enslaved women for a decade.

I understand that you’ve

fathered two dozen children and taken no responsibility for them.

I understand that Hannah died because of you, because

of your depravity, your absolute disregard for human life.

Finch’s expression turned cold, utterly devoid

of warmth or humanity.

He stood slowly, deliberately, his considerable height

and bulk suddenly menacing, casting a long shadow over Thorne.

“Be very

careful, doctor,” he said quietly, his voice a low, dangerous growl.

You’re

making serious allegations without a shred of proof.

Allegations that could be considered slanderous, damaging to my

reputation and my business.

Do you understand the consequences of such slander in this community? I don’t care

about consequences, Thorne said.

Though even as he said it, he knew it wasn’t

entirely true.

A part of him, the rational, self-preserving part, screamed

in protest, “Someone needs to speak the truth.” The truth?” Finch laughed, a harsh,

bitter sound that held no mirth.

The truth is that you’re a lonely, bitter man who’s been drinking too much and

letting his imagination run wild.

The truth is that you have no proof of anything that would stand up in any

court of law.

The truth is that if you repeat these accusations to anyone else,

I will ruin you.

I’ll have you run out of this county, a disgraced charlatan.

I’ll make sure you never practice medicine again anywhere in this state.

Do you understand me, doctor? Thorne

stared at him at the cold certainty in his eyes at the absolute unyielding

power emanating from him.

And in that moment, he felt his courage crumble, his

desperate resolve dissolve into a bitter, impotent despair.

Finch was right.

He had no proof that

would stand up in any court.

He had suspicions, circumstantial evidence, a

pattern that could be explained away as coincidence by anyone determined to do so.

And Finch had power, connections,

the full unyielding weight of the social order behind him.

Thorne was a single

insignificant man against an entire system.

“Get out of my office,” Finch said, his voice like ice, dismissing

Thorne as if he were an annoying fly.

And if you value your livelihood, your reputation, or even your continued

presence in this town, you’ll forget this conversation ever happened.

You’ll forget everything you think you know.

Thorne left, his legs shaking, his heart pounding a frantic rhythm against his ribs.

He had confronted Finch, and he

had lost.

Nothing had changed.

Nothing would change.

The silence, he realized,

was not just a choice, but a weapon.

The confrontation with Finch marked a profound turning point for Thorne.

He

withdrew further into himself, his practice dwindling as his reputation for instability grew.

The whispers about

poor Dr.

Thorne became louder, more frequent.

He spent his days in his office, pouring over his ledger, adding

new entries as more red-haired children were born, each one a fresh stab of pain.

He had given up any hope of

justice, any hope of stopping Finch.

All he could do now was what Ara had suggested.

Bear witness.

Remember

document.

His ledger became his confessional.

His silent scream against the injustice.

His once neat office

became cluttered, dusty.

Books lay open, forgotten.

The scent of stale tobacco

and whiskey mingled with the faint lingering smell of antiseptic.

He rarely ventured out, preferring the

company of his thoughts, however dark, to the polite, piting glances of the town’s people.

He was a ghost, haunting

his own life, a man consumed by a truth too terrible to speak.

In the summer of

1857, as the oppressive heat of July settled over Willow Creek, Thorne

received an unexpected visitor.

A young woman, perhaps 25 years old, appeared at

his office door.

She was well-dressed in a simple but elegant traveling suit, her

hair neatly pinned beneath a modest bonnet, her eyes bright with an intelligent, unwavering gaze.

She

introduced herself as Miss Abigail Winters, a teacher from Boston who had come south to work with a missionary

society dedicated to improving conditions for enslaved people.

Thorne

was immediately wary.

Abolitionists were not welcome in Alabama, and anyone

associated with them was viewed with deep suspicion, often with outright hostility.

He had heard stories of such

individuals being run out of town, sometimes violently.

But Miss Winters was persistent.

Her quiet determination

of force Thorne found difficult to resist.

Eventually, he agreed to speak with her, ushering her into his dimly

lit office.

I’ve been traveling through the South,” she explained, her voice

clear and calm as she sat opposite Thorne, her hands clasped neatly in her

lap.

Documenting the conditions of slavery, not for immediate publication.

Doctor, I’m not foolish enough to think I could publish such things openly in this climate, but for the historical

record, so that someday when this terrible institution is finally abolished, people will know the truth of

what happened here, the full unvarnished truth.

A noble goal, Thorne said dryly,

his voice raspy from disuse.

He poured himself a small measure of whiskey,

offering none to his guest.

and a dangerous one.

Perhaps, Miss Winters

acknowledged her gaze steady, but necessary.

I’ve heard rumors, Dr.

Thorne, about unusual patterns in this county, children born with distinctive

features.

I was hoping you might be able to provide some insight.

Your name was mentioned by a few of the midwives I

spoke with, particularly an older woman named Aara on the Bowmont plantation.

She spoke highly of your kindness and your keen eye.

Thorne felt his heart

begin to race, a frantic flutter in his chest.

How had she heard? Who had told

her? Ara, of course.

He studied Miss Winter’s face, trying to gauge her

intentions, her sincerity.

Was she truly seeking truth, or was she merely a

provocator, a danger to everyone involved? Why would you think I’d know anything about that? He asked, his voice

guarded.

because you’re the doctor who delivers most of these children.

Miss

Winter said simply, her directness disarming, and because I’ve been told you’re a man of conscience, troubled by

what you’ve witnessed.

Aar said you were a man who carried the truth like a heavy

stone.

For a long moment, Thorne said nothing.

The silence in the room was

thick, punctuated only by the buzzing of a fly against the window pane.

Then

slowly, deliberately, he reached into his desk drawer and pulled out his ledger.

He opened it to the pages where

he had meticulously documented the births, the dates, the plantations, the distinctive features of the children.

The faded ink, the precise handwriting were a stark contrast to the chaos and

despair they represented.

27,” he said quietly, his voice barely a whisper, as

if speaking the number aloud might shatter the fragile piece of the room.

27 girls in 13 years, all with red hair and pale skin, all born to enslaved

women, all with the same father, though his name is never spoken.

Miss Winters

leaned forward, her eyes scanning the pages, her expression one of grim understanding.

Do you know who the

father is? Yes, Thorne said the word a bitter taste in his mouth.

But I can’t

prove it.

Not in any way that matters here, and even if I could, it wouldn’t matter.

He’s too powerful, too

well-connected.

The entire community protects him, either actively or through their silence.

They are all complicit.

Tell me his name, Miss Winters said, her voice firm, unwavering.

Let me decide

what can be done with the information.

My society has connections, doctor.

We

have ways of documenting these truths, even if we cannot act on them immediately.

Thorne hesitated.

To speak

Finch’s name aloud to someone outside the community felt like crossing a line

from which there would be no return.

It felt like a betrayal of the very silence

that had protected him, however imperfectly.

But what did he have to lose? His

practice was already failing.

His reputation was already in tatters.

And perhaps, just perhaps, Miss Winters,

with her quiet strength and her distant connections, could do something with the information that he, a broken man in a

broken system, could not.

Perhaps his years of silent suffering, his

meticulous documentation, might finally serve a purpose beyond his own despair.

“Alistister Finch,” he said, the name of Venomous Hiss on his lips.

the cotton

broker.

He has access to every plantation in the county.

He’s been doing this for over a decade, and no one

will stop him.

No one can.

Miss Winters wrote the name carefully in a small notebook she had produced from her bag,

her pen scratching softly.

And the mothers, have any of them spoken about

this? Have they named him? They can’t, Thorne said, shaking his head.

To speak

would be to invite punishment, to risk being sold away, separated from their other children.

They protect themselves

and their children through silence.

It is their only defense.

Miss Winters

nodded slowly.

Her gaze thoughtful.

I understand.

Dr.

Thorne, would you be willing to let

me copy these records? I promise they’ll be kept confidential, used only for

historical documentation, for a future when such truths can be openly acknowledged.

Thorne considered the request.

His ledger was the only evidence he had, the

only proof that he hadn’t imagined the pattern, that he wasn’t simply a madman seeing conspiracies where none existed.

To hand it over, even to allow it to be copied, felt like relinquishing the last thing of value he possessed.

the last

tangible proof of his sanity.

But what good was it doing him? He had kept these records for 13 years, and they had

accomplished nothing but to deepen his despair.

Perhaps in Miss Winter’s hands,

they might serve some purpose, might contribute to some future reckoning, a distant echo of justice.

Perhaps Aar’s

words, “Maybe someday someone will want to know the truth.

We’re not entirely without hope.”

Yes, he said finally, his voice barely audible.

You may copy them.

Miss Winters spent

the next several hours carefully transcribing Thorne’s entries into her own notebook, her pen moving swiftly and

precisely across the pages.

The only sounds in the room were the rustle of paper, the scratch of her pen, and the

distant mournful cry of a whip or will.

When she finished, she closed her notebook, her face grave.

She thanked

him profoundly, her eyes conveying a deep respect and understanding, and prepared to leave.

“Dr.

Thorne,” she

said at the door, her voice soft but resolute, “I want you to know that what you’ve done, keeping these records,

bearing witness, it matters.

Even if it doesn’t feel like it now, even if

justice seems impossible in this time, the truth has value.

Someday people will

want to know what really happened here.

And because of you, because of your courage to document, they’ll be able to.

After she left, Thorne sat alone in his office, the ledger still open on his

desk, feeling strangely empty.

He had finally told someone, finally shared the

burden he had been carrying for so long, but he felt no relief, no sense of catharsis.

If anything, he felt more

hopeless than before, because he knew with a certainty that went bone deep,

that nothing would change.

Finch would continue his predations.

The red-haired

children would continue to be born, and the community would continue its conspiracy of silence, its complicity in

the face of unspeakable cruelty.

Just when we thought we’d seen it all, the depths of human depravity and the

resilience of those who suffer in silence, the story takes another turn.

A testament to the enduring power of

truth.

However long it takes to emerge from the shadows.

Doctor Elias Thorne

died in the winter of 1859, 2 years before the outbreak of the Civil War

that would tear the nation apart and ultimately irrevocably end the institution of slavery.

He died alone in

his small house.

His practice long since abandoned.

His reputation in ruins, a

forgotten man in a town that had chosen to forget him.

The official cause of death was listed as heart failure, a

convenient diagnosis.

But those who had known him suspected it was more a failure of the spirit, a slow surrender

to despair, a heart broken by the weight of unspoken truths.

His possessions were

sold to pay his meager debts.

His medical instruments, his books, his worn furniture, all went to auction,

scattered to the winds.

His ledger, that careful, meticulous record of 13 years

of observation and documentation, was found among his papers.

The executive of

his estate, a local lawyer who had never much liked Thorne, glanced through it,

saw only medical notations that meant nothing to him, and tossed it into a dusty box of miscellaneous papers to be

stored in the courthouse attic, forgotten amidst forgotten files.

Alistister Finch attended Thorne’s

funeral, as befitted a prominent citizen, paying respects to a fellow professional.

He stood at the graveside,

his red hair now liberally stre with gray.

his face a picture of solemn respect.

He listened to the brief

peruncter eulogy delivered by Reverend Blackwell.

If he felt any guilt, any

remorse, any acknowledgement of the role he had played in Thorn’s decline, his face betrayed nothing.

He was a man

utterly devoid of conscience, a master of deception, his public persona an

impenetrable shield.

The red-haired children continued to be born, though less frequently as Finch

aged, his vigor perhaps waning or his opportunities diminishing.

By the time the Civil War broke out in 1861, there were 31 of them, scattered

across the county, ranging in age from infancy to 17 years.

Some had been sold

away, disappearing into the vast anonymous landscape of slavery, their fates unknown.

Others remained on the

plantations where they had been born, growing up in the shadow of their unagnowledged paternity.

Their fiery

hair a constant silent question.

When the war came, it brought chaos and

destruction to Alabama.

Plantations were burned.

Families were scattered.

The

entire social order that had sustained slavery collapsed in a mastrom of fire and blood.

In the tumultuous aftermath

during the difficult years of reconstruction, many of the red-haired girls, now young women, gained their

freedom.

Some left Alabama, seeking new lives in the north or west, hoping to

escape the ghosts of their past.

Others remained, building lives in the only place they had ever known, their roots

too deep to sever.

A few of them eventually learned the truth about their father.

The knowledge came in different

ways.

A whispered conversation from an aging midwife, a deathbed confession from a former house servant, a chance

encounter with someone who had known the secret all along.

Some were devastated by the revelation, the truth of bitter

poison.

Others had always suspected, had seen their own reflection in a mirror,

and wondered at the stark contrast between their features and those of their mothers, their siblings.

None ever

received any acknowledgement from Finch, any support, any recognition of their

existence.

They were simply the unagnowledged, inconvenient truths of a

powerful man’s life.

Alistister Finch himself survived the war.

Though his

business was ruined, his fortune decimated by the collapse of the cotton economy.

He lived on for another decade,

a diminished figure in a changed world, a relic of a bygone era.

He died in 1875

at the age of 73, a seemingly peaceful end to a life of quiet depravity.

His obituary in the local newspaper praised his contributions to the community, his business acumen, his

charitable works, his unwavering commitment to the prosperity of Willow Creek.

There was no mention of the children he had fathered, no acknowledgement of the lives he had damaged, no hint of the

terrible secret that had defined his life, a secret he had carried to his grave with the same impunity with which

he had lived.

The ledger that Doctor Elias Thorne had kept so carefully

remained in the courthouse attic for decades, forgotten and gathering dust, a silent witness to a forgotten history.

It was finally discovered in 1923 during a renovation project.

A young cler

sorting through boxes of old decaying papers came across it and intrigued by

the careful handwriting and detailed medical notations brought it to the attention of the county historian.

The

historian, a meticulous woman named Margaret Thornton, recognized the significance of what she was reading.

She spent months researching, tracking down descendants of the people mentioned in the ledger, piecing together the

story that Thorne had documented but never told.

She wrote a paper about her findings, presenting it at a regional

history conference in 1925.

The paper caused a minor sensation in academic circles, a ripple of discomfort

and fascination, but it was largely ignored by the general public.

The descendants of the plantation families,

now respectable citizens of the new south, were horrified by the allegations and worked to suppress the story, to

bury it once more beneath layers of denial and convenient historical narratives.

The paper was never

published in a major journal, and Margaret Thornton’s groundbreaking research was quietly shelved, deemed too

controversial, too unsettling for the prevailing narrative of a romanticized past.

But the truth once uncovered has a

way of persisting, of finding cracks in the edifice of silence.

Copies of Thornton’s paper circulated among historians and researchers.

The story of the red-haired children of Alabama became a footnote in academic studies of slavery, a dark example of

the systematic abuse that had been endemic to the institution, a stark reminder of the human cost of absolute

power.

And somewhere in archives and attics, in faded family bibles and

whispered oral histories, the descendants of those 31 red-haired girls

preserved their own memories.

They knew who they were, knew the truth of their

ancestry, even if the wider world chose to forget or ignore it.

They carried that knowledge forward.

A burden and a testament, a reminder that

some secrets, no matter how carefully guarded, eventually come to light, even

if it takes generations, Dr.

Elias Thorne had spent the last years of his

life in despair.

Convinced that his documentation had been meaningless, that

the truth would die with him unheard and unagnowledged, he never knew that his

careful records would survive, that they would eventually contribute to a broader

understanding of the horrors of slavery, of the insidious ways in which power corrupts and silence enables.

He never

knew that the act of bearing witness, of simply recording what he had observed,

would matter.

But it did matter.

It does matter because history is not just the

story of the powerful and the victorious.

It’s also the story of those who suffered in silence, whose lives

were shaped by forces beyond their control, whose existence was denied or erased by those who found it

inconvenient.

The red-haired girls of Alabama were real.

Their mothers were

real.

Their suffering was real.

And though justice was denied them in their own time, the truth of their existence

endures, a testament to the human capacity for both cruelty and resilience.

A reminder of the terrible

price of silence, and a challenge to those of us who inherit these stories to

ensure that such injustices are never forgotten, never repeated, never allowed to hide in the shadows of history.

If

this story has moved you, if it’s made you think about the hidden histories that surround us, please consider

sharing it.

These are not easy stories to tell or to hear, but they are

necessary.

They remind us of where we’ve been and challenge us to do better.

Subscribe to Liturgy of Fear for more journeys into the forgotten corners of American history.

And remember, the past

is never truly past.

It lives on in the stories we tell.

The truths we uncover

and the lessons we choose to

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load