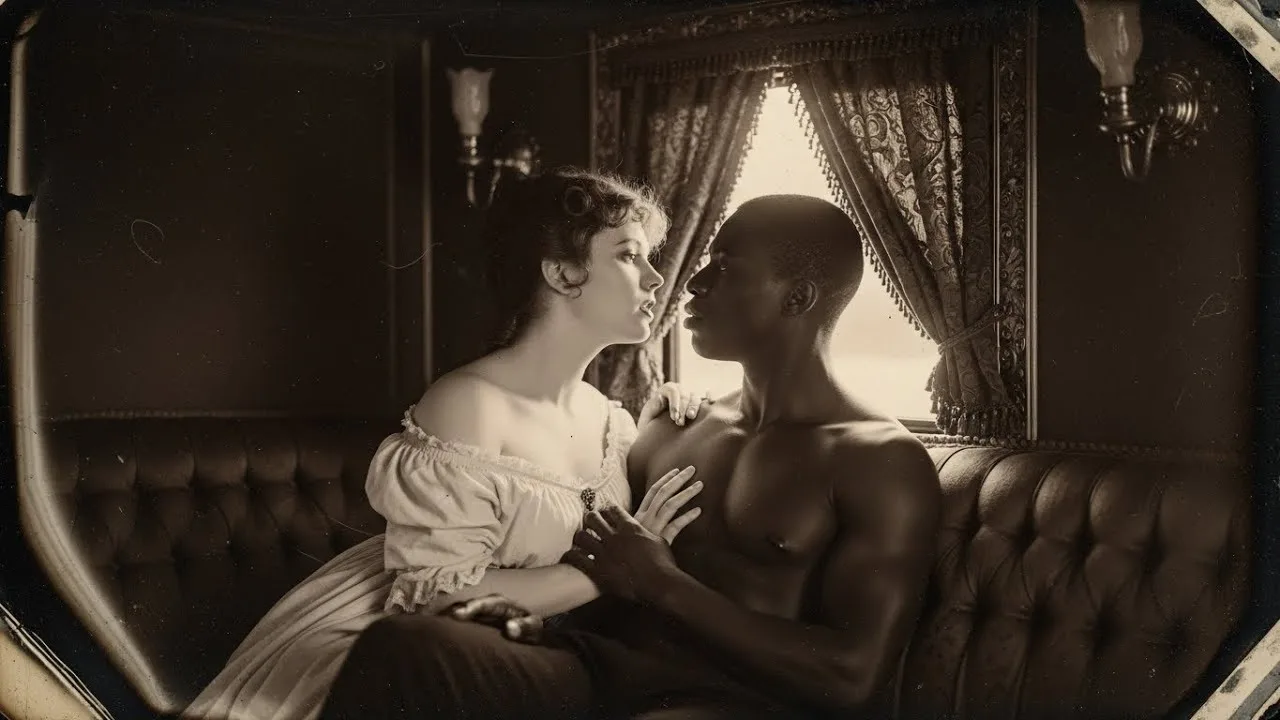

In 1837, the New Orleans slave market smelled of salt, sweat, and iron.

Amid the auction chants and ledger talk—lots, bids, profits—an incongruous sound cut through: the hush of black mourning silk.

Anora Bellamy, widow of a Mississippi plantation, stepped down from her carriage as if entering confession.

A folded paper in her glove, a veil across half her face, and a secret heavy enough to tilt a life.

She didn’t come to buy cheap labor.

She came to buy a particular man—Isaac—once owned by Bellamy, sold ten years prior, marked by a faint crescent scar beneath his right eye.

The reason she offered was modest enough: “a man my late husband trusted,” “the estate needs him.” The real reason was more dangerous: he was father to Jameson, the stiff-backed fourteen-year-old in the carriage, gray-eyed and watchful in a way that belonged to someone other than the man buried under Bellamy soil.

—

Setting: Bellamy Plantation, Numbers in Ledgers and Truth Beneath Floorboards

Bellamy looked like a “white lie that learned to walk on columns” in Mississippi flatlands: a two-story big house, live oaks, kitchen, smokehouse, barns, slave quarters, cotton fields stretching to the horizon.

Edwin Bellamy—Anora’s late husband—was an archetype of planter order: less lash than ledger, but never mercy.

He wrote “lots,” not names.

Most sins lived in margins.

After Edwin died, Anora turned ledgers and found a “thin ribbon of ink”—the sale of a driver with a scar under his eye, moved by river and rail—tucked into the back of an account book.

Paper can hide a very large wrong.

She carried that line to New Orleans, paid cash without haggling, and brought Isaac back to Bellamy—a choice that would open new cracks in an old, already rotting structure.

—

Characters and Motives: Anora, Isaac, Jameson, Rufus, Victor, Lucas

– Anora Bellamy: widow, estate manager, balancing the roles of victim and accomplice.

She buys Isaac out of moral debt, to keep him near Jameson, and because she can’t bear living off the sale of her child’s father.

– Isaac (Cole): driver, horseman, literate in scripture and sums, calm but not compliant.

He knows the law won’t recognize him as father; claiming the boy would trigger whips.

He still steps into a lash meant for a child.

– Jameson Bellamy: fourteen, gray eyes, walking between pride and unease.

Quick learner, hardheaded, and unaware of his parentage—until truth lands in church.

– Rufus Klene (overseer): likes “order,” loves the whip, hates secrets.

He spots every “improper” glance between stable and house and waits for his moment.

– Victor Bellamy (Edwin’s brother): sharp, circling inheritance, holding a second will that ties Jameson’s future to Isaac’s bondage—if “property” is freed, land shifts to Victor.

– Lucas Hail: borderlands traveler selling plows and news.

He watches clean, carries documents, knows back roads, and says it plain: “Convenience never saved anyone.”

—

Return: Horses, Whips, and Looks You Can’t Name

Isaac returned in irons, but upright.

Anora placed him with the carriage stock.

Rufus pushed for the fields.

The order “belongs in the stables” stuck like a splinter in Anora’s throat; she forced it down.

Days later, she had reasons to visit—lameness, harness wear, dryness in leather—then “history.”

On a storm-heavy afternoon, Anora said: “I didn’t know you were sold until I saw your name in the ledger.” Isaac said: “You fed that boy with your husband’s food, raised him in that man’s house, taught him that man’s pride.

If I claim him, they beat me, you lose him, and he loses you.

I chose silence.” This was not a romance.

It was a negotiation between two adults trapped by a system.

Rufus waited for a pretext.

A twelve-year-old faltered in heat, rawhide hissed, Isaac stepped in front.

Two lashes struck his chest.

He didn’t flinch.

Anora arrived and snapped the whip with her voice: “I speak for this place.” Rufus lowered the strap, not the grudge.

A fragile equilibrium shook.

—

Disclosure: The Biggest Sermon Didn’t Come from the Pulpit

Lucas placed a paper on Anora’s desk: a copy of Isaac’s sale bill bearing Edwin’s hand.

A spark.

He brought another fire: a second will—if Isaac is freed, Jameson’s inheritance collapses to Victor.

“Morality” and “survival” became enemies overnight.

Anora wrote a confession.

On Sunday, in church, Victor stood “for community morality,” implying “widow, slave, New Orleans.” The minister asked if she wished to respond.

She stood, said Edwin’s name without “Mr.,” and opened the moral ledger: secret sales, forced bodies, children in cabins, a father sold to hide shame.

“Look at lighter-skinned children’s faces, sale papers, quiet trips,” she said.

Then, “Look at my son—Jameson is not Edwin’s blood.”

The church erupted.

Some called her mad; some called her brave.

The minister demanded “repentance”: cast Isaac out.

Anora said, “If I cast him out, I cast out justice.” The sermon ended in a tear that would not reseal.

—

Legal Outcomes: When Myth Cracks, Paper Changes Meaning

Victor moved: presented the second will, petitioned the court to review Anora’s stewardship, insisted that Jameson’s rights depended on keeping certain “property” in chains.

Lucas countered with documents—fraud, evasions, quietly purchased favor—pricking conscience.

The court chose “practical resolution”: land to Victor, the big house and 1,000 acres to Caroline for life then to the children; Anora left with a small town house and a thin stipend.

Isaac received manumission—a paper of freedom—and a path north.

Justice didn’t win big.

But it showed up.

—

Departure: Freedom Isn’t Heaven, But It’s a Door

On the last night, Isaac came to Anora’s small house.

She handed him a Bible with three names inside: Isaac, Anora, Jameson—no “Mr.,” no “property of,” just names.

He said he couldn’t carry much.

She said, “Tear the page.”

They spoke the true thing they had never said: “In another world—free, young, and in another country—did we have love?” He said, “Something real,” not the kind sermons sanction, but enough to go forward without turning it into a weapon.

Lucas waited at the edge of town.

Isaac climbed up.

On a hill, Jameson stood, watching without speaking.

Pride, hurt, confusion knotted him.

His feet brought him anyway.

The wagon shrank to a speck and vanished.

—

Aftermath: War, Reconstruction, and a Legacy

War tore the South; law was rewritten in blood.

Bellamy broke—sold and seized.

Victor died bitter, wealth eroded.

Anora aged in a small house, quiet dignity intact.

Jameson came back around as the first shock uncoiled into understanding: his mother’s truth changed him—and saved him from becoming another Edwin.

A letter arrived from the north.

Lucas wrote: Isaac worked in a shipyard by a cold river, helped the newly free, carried a slip of paper with three names until a lung sickness took him.

Jameson carved a simple marker: “Isaac Cole—father (whether the law admits it or not).” He stood there feeling the weight of names and understood that some stories live only in the ledgers people keep in their hearts.

—

Analysis: Motives, Systems, and the Price of Truth

– Buying as confession: Anora purchased Isaac to pay a debt she could never fully settle—and to keep justice within reach of her son’s life.

– Fatherhood denied by law: Isaac refused a claim that would harm the boy.

He stepped into danger quietly, without ceremony.

– Inheritance booby-trapped: Edwin wrote a second will to make freedom cost a fortune—a system designed so virtue and survival can’t share a room.

– Myth as governance: Bellamy’s reputation was currency.

Crack the myth, and statutes shift under judges’ feet.

– Community versus conscience: The minister preached order; the widow preached truth.

Both had audiences.

Only truth moved the ledger lines.

– Freedom as logistics: Lucas represented quiet routes, not speeches.

Paperwork and timing saved lives when force would have destroyed them.

—

Ethical Questions the Story Won’t Let Go Of

– If virtue costs survival, which do you choose?

– Can a woman be both victim and accomplice and still tell the truth in time?

– What is a father when the law forbids the word?

– Does justice sometimes look like scandal before it looks like peace?

– Who writes history: the man with the whip, the woman with the ledger, or the neighbor with the rumor?

—

Key Takeaways: Why This Story Still Matters

– One confession can turn a plantation into a courtroom—and a sanctuary.

– Systems hide harm in margins; reading margins is resistance.

– Paper frees as often as it binds—if you know what to file and when.

– Love can be real and impossible; justice can be partial and necessary.

– The law is a scaffold; conscience is the builder.

Choose carefully.

—

Closing: A Quill, a Bell, and a Door Left Open

In that market, a widow bought more than labor.

She bought a name back from a ledger and pulled a hidden father within sight of a son.

She shattered a myth to free a man and lost a house to save a boy.

It wasn’t clean.

It wasn’t complete.

It was justice enough for the next morning.

On a hill above a small graveyard, a wooden marker reads “Isaac Cole—father.” Below it lies a story the county tried to forget and a truth the family refused to let die: sometimes the only way through a rigid system is to tell a hard truth in a room that prefers polite lies—and to accept the price that follows.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load