The Picture That Hid a Family’s Secret

On a crisp October afternoon, Margaret Foster stepped into the chilly, echoing halls of the Dawson estate.

For thirty years, she’d made her name as Philadelphia’s most meticulous photography restorer, able to identify 19th-century chemical processes by touch and sight alone.

But as she sorted through six boxes of old photographs in a third-floor storage room, she found an image that would change everything she thought she knew about family, secrecy, and the power of a photograph.

Wrapped in tissue at the bottom of the fourth box was a portrait so technically perfect, so beautifully composed, that Margaret’s practiced eye lingered.

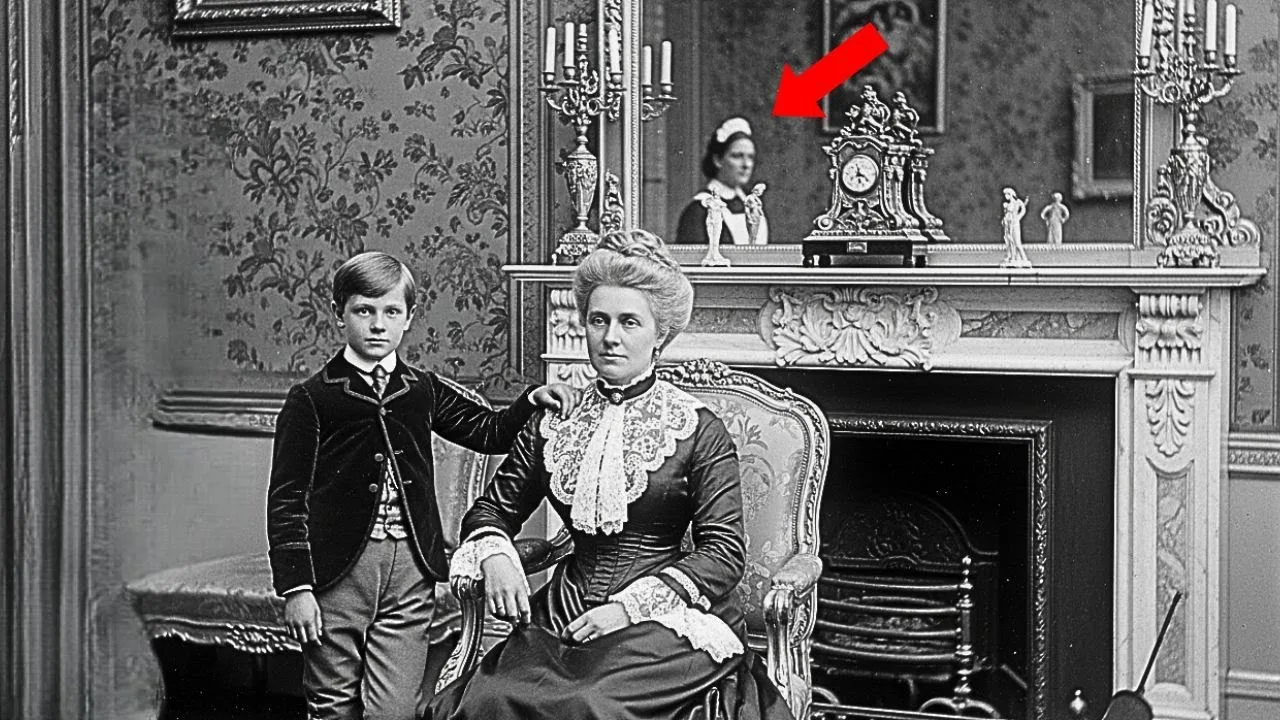

The photograph showed a parlor scene from the spring of 1891: a woman in her thirties sat in an ornate chair, dressed in expensive dark silk and elaborate lace.

Beside her stood a boy of about eight, his hand resting on his mother’s shoulder.

Their faces wore formal smiles, their posture impeccable.

The setting radiated affluence—rich wallpaper, marble fireplace, gilded mirror, and a crystal chandelier overhead.

On the back, in faded ink: “Mrs.

Victoria Aldridge and Master Henry Aldridge.

Spring 1891.

Aldridge residence.”

Margaret placed the photograph in her portfolio, unsettled by something she couldn’t quite name.

The woman’s smile seemed sad, the boy’s eyes unusually intense.

But it was the background—the enormous mirror behind them—that kept tugging at her mind.

## Zooming in on the Mirror

The next morning, Margaret scanned the Aldridge photograph at maximum resolution.

As the image appeared on her monitor, she began her methodical examination.

The photograph was in remarkable condition—minimal foxing, no major tears, just slight edgewear.

She zoomed in on Victoria Aldridge’s delicate features and substantial jewelry, then on Henry’s guarded expression and tense grip on his mother’s shoulder.

But when Margaret reached the mirror, her breath caught.

She increased magnification, adjusting digital enhancement to bring out every detail.

In the reflection, she saw the parlor from the opposite angle: the photographer’s large-format camera on its tripod, a dark cloth draped over it, and—partially visible—a woman in a servant’s uniform, hands clasped, watching the session.

Her face, though only partly visible, showed striking features.

She appeared younger than Victoria, perhaps in her mid-twenties.

Her posture suggested both attention and tension.

Margaret studied Henry’s features, then the servant woman’s.

The resemblance was unmistakable.

## Tracing the Aldridge Family

Margaret spent hours searching genealogical databases for information about the Aldridge family.

The 1890 census listed Victoria Aldridge, head of household, age 34, widow; Henry Aldridge, son, age 7; four servants—cook, housemaid, laundress, and governess.

Thomas Aldridge, the husband, had died in 1888 of pneumonia at age 38.

The obituary described him as a respected merchant who left his wife comfortably provided for.

But something didn’t add up.

If Henry was seven in 1890, born around 1883, and Thomas died in 1888, Henry would have been five at the time of his father’s death.

Yet, Margaret found no birth record for Henry Aldridge in Philadelphia in 1883.

She expanded the search—no record in surrounding counties or Pennsylvania cities.

Odd for a family of means.

Margaret tried a different approach—searching for Victoria Morrison before marriage.

The 1870 census showed William Morrison, shopkeeper, his wife Eleanor, and two daughters: Victoria, age 14, and Caroline, age 12.

Caroline, the younger sister.

Caroline appeared in the 1880 census, aged 22, living with her parents, working as a seamstress.

Then, she vanished from official records—no marriage, no death, no census listing.

In 1890, Caroline Morrison was gone from the records, just as Henry Aldridge appeared in Victoria’s household.

Margaret returned to the 1890 census entry.

Among the servants: Mary, cook; Sarah, housemaid; Jane, laundress; Caroline, governess.

Caroline—the governness.

Margaret’s hands trembled as she zoomed in on the servant woman in the mirror.

The resemblance to Henry was undeniable.

## Uncovering the Truth

Margaret brought her findings to James Chen, head archivist at the Philadelphia Historical Society.

Together, they examined the photograph and census records, noting the absence of Henry’s birth record and Caroline’s disappearance from public life.

“Illegitimate births were often handled this way,” James said.

“A woman would have the baby secretly, and a married sister might claim it as her own.

But Caroline didn’t go away—she stayed as the governness to her own son.”

James retrieved the Aldridge estate papers and family correspondence.

Near the bottom of a folder, they found a letter dated November 1883, addressed to “my dearest sister Victoria.” Margaret read aloud:

> “My situation has reached its inevitable conclusion.

The child arrived last week, a healthy boy.

Mother and father insist I give him to the asylum, but I cannot bear it.

You wrote that you might help.

Please, Victoria, if you meant it.

I am desperate.

Your loving sister, Caroline.”

They found three more letters from Caroline to Victoria, spanning late 1883 to early 1884.

The second letter showed relief:

> “Thomas has agreed to your proposal.

I cannot express my gratitude.

I will be the most devoted governness in Philadelphia.

No one will suspect.

Your eternally grateful sister, Caroline.”

The third letter, February 1884:

> “I am settling into my role.

Henry thrives and I am grateful to see him daily.

Victoria, you are the best of sisters.

The neighbors accept the story without question.

Mrs.

Thompson complimented me on how naturally I handle the baby.

If only she knew.”

The final letter, September 1884:

> “Some days I want to scream that he is mine, that these hands that feed and comfort him have the right to be called mother.

But then I see you with him at church and I know this arrangement is his only chance at a proper life.

I am his governness.

You are his mother.

This is how it must be.

Caroline.”

The truth was clear: Caroline was Henry’s real mother, forced by circumstance and family shame to surrender her son’s identity to her sister.

## The Cost of Secrecy

Margaret and James found more evidence—William Morrison’s letter to Victoria in late 1883:

> “Your mother is devastated.

The shame Caroline has brought upon this family is unbearable.

She refuses to name the man.

The child must go to the asylum.

If you wish to help your sister, that is your affair.

But do not ask us to accept this situation.”

Caroline was disowned.

Victoria and Thomas saved her by creating an arrangement: Caroline stayed close as the “governess,” and Henry gained a legitimate name.

Margaret traced Henry’s childhood through school records and society pages.

He excelled academically but remained a solitary, intense boy.

Caroline, meanwhile, was always listed as the “governess,” invisible in public life except for receipts showing advanced educational materials—Latin texts, French literature, art supplies.

A letter from Victoria to a friend in 1896 mentioned Caroline obliquely: “Henry’s governess is most devoted to him.

Sometimes I think she loves him more than is strictly professional, but I cannot fault her dedication.”

Caroline’s sacrifice was total: her reputation, inheritance, and chance at her own family—all surrendered so she could remain near her son.

## The Secret Discovered

Margaret’s research led her to Henry Aldridge’s own papers at the University of Pennsylvania.

Among his journals, she found an entry from October 1898:

> “I discovered something today that has shattered everything I believed.

I was searching for a book in mother’s study when I found letters hidden in a drawer.

Letters from Caroline to mother dating from before I was born.

I read them all.

I know now what they never intended me to know.

Caroline is my mother, my real mother, and the woman I have called mother my entire life is actually my aunt.”

Henry’s subsequent entries chronicled his emotional turmoil.

He watched Caroline, seeing her differently—her love, her pain, her sadness.

He confronted Victoria, who wept and explained the arrangement.

She begged him not to tell Caroline that he knew.

Henry chose to keep the secret, maintaining the fiction for the sake of both women.

## The Burden of Truth

Henry’s journals revealed how knowledge of his true parentage shaped his life.

He never told Caroline he knew, maintaining their “governess-student” relationship even as he struggled internally.

His letters to Victoria remained formal; to Caroline, intimate and philosophical.

After Victoria’s death in 1912, Caroline was finally acknowledged as Victoria’s sister in her obituary.

Victoria’s will left Henry the estate and Caroline $15,000, describing her as “my beloved sister who has devoted her life to our family with selfless dedication.”

Caroline left the Aldridge household, living modestly until her death in 1930.

Henry visited her weekly, and at her deathbed finally whispered, “I know, mother.

I’ve always known.” Caroline smiled, closed her eyes, and was gone.

## The Photograph’s True Meaning

Margaret stood in her workshop, the restored photograph now mounted in an archival frame.

She had spent three months researching the Aldridge family, uncovering a story hidden for nearly a century.

The photograph would be displayed at the Philadelphia Historical Society alongside letters, documents, and journal excerpts.

Looking at Caroline’s reflection in the mirror—the young woman standing in the doorway, her hands clasped, her face composed—Margaret understood the photograph’s real significance.

Caroline couldn’t stand beside her son as his mother, but she found a way to be documented with him anyway.

Her reflection was proof that she existed, that she loved him, that she was there.

James Chen, viewing the final restoration, nodded.

“Henry kept this photograph his entire life.

It was among his most valued possessions.”

Margaret thought of all three: Victoria, who gave a child legitimacy at the cost of living a lie; Caroline, who sacrificed everything for love; and Henry, who bore the burden of truth to protect the women he loved.

“The photograph tells the truth now,” Margaret said.

“Caroline isn’t invisible anymore.

Her reflection is there for anyone who looks closely enough.”

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load