Samuel learned to live without sound.

At twelve, he could pass from pantry to parlor like a draft—present enough to pull a napkin edge, absent enough to be forgotten.

Old Martha said it was why he’d lived this long inside Thornfield Mansion.

Keep the cups from chattering, the boards from speaking, your eyes from telling your thoughts.

Master William liked his house like he liked his ledgers: neat, silent, perfectly in his control.

Samuel studied that control the way a boy studies weather.

He memorized the routes Master took between study and porch.

He noted when Mrs.

Eleanor’s fingers worried at her wedding ring and the house slowed around her to accommodate a mood.

He counted the seconds it took for hot water to carry from the scullery to the master’s bath so he would arrive neither too early to irritate nor too late to invite lecture.

Seeing everything had kept him safe.

He did not yet understand it might kill him.

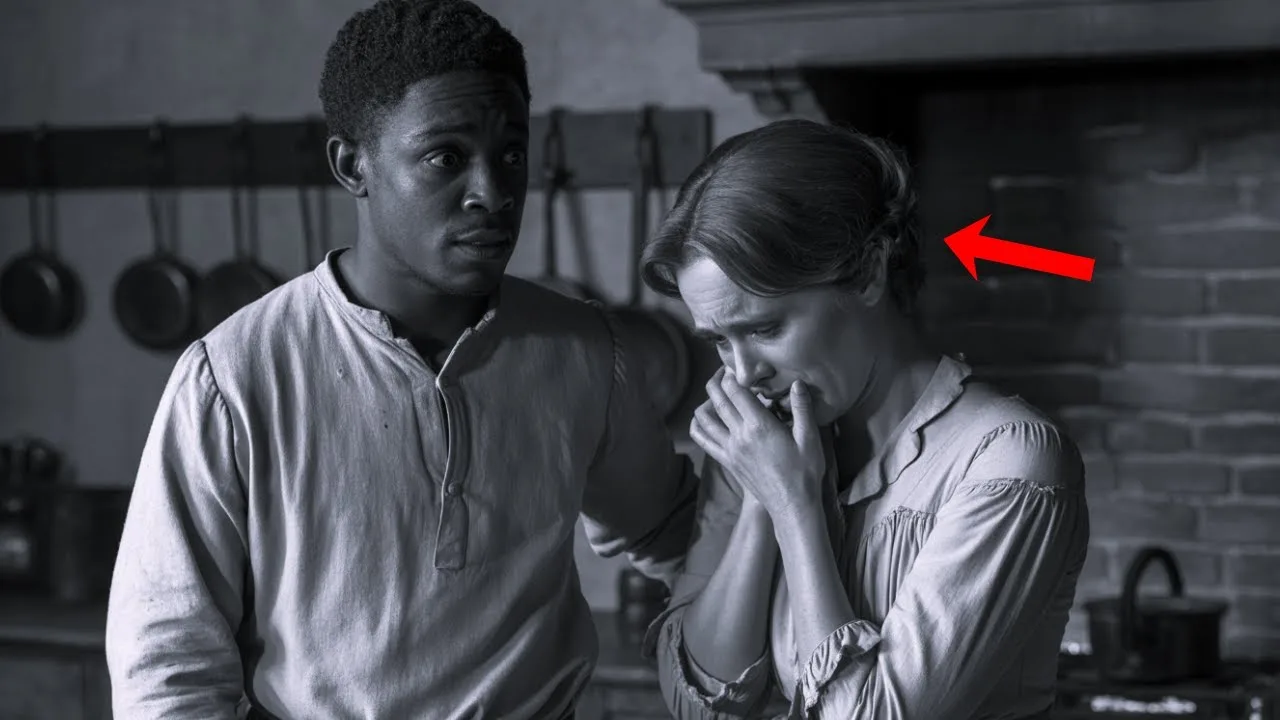

On a sweltering Tuesday, carrying fresh linens down the back corridor, he heard a sound the house did not make: crying.

Not a child’s whimper in the quarters.

Not a kitchen girl bitten by steam.

Softer, muffled, leaking through the crack of the kitchen door like heat.

Slaves did not cry where they could be heard.

Samuel stopped.

He drifted to the frame and looked.

Mistress Eleanor was at the table with a handful of papers crumpled in her fist, shoulders shaking.

Her composure—a thing she wore like a jacket in front of other white women—had slipped to the floor.

Tears tracked lines through powder on her cheeks.

Her mouth was set hard, as if holding back words that would cost too much spoken aloud.

Samuel shifted his weight to leave and the old floorboard betrayed him with a groan.

Her head snapped up.

Hazel eyes found him through the distance.

He froze.

The look that met him was not outrage.

It was recognition, dangerous as a knife left out.

“Come in,” she whispered.

“Close the door.”

He should have turned and fled.

He closed the door.

“What’s your name?” she asked, scrubbing her face and attempting, absurdly, to pat her hair into its usual neatness.

“Samuel, ma’am.”

“You’re William’s house boy.” Not a question.

She looked at him as if seeing past his skin to the part of him that had learned to read empty rooms.

“Can you read, Samuel?”

The air went thin.

Words drifted out of him: “Some, ma’am.” Old Martha’s voice rose from nights spent bent over stolen newsprint with a stub of charcoal: Keep your head down, your ears open, your thoughts hidden.

But the truth stood between them anyway, and Mistress Eleanor nodded as if she’d only confirmed a thing she’d already pinned to a map in her head.

“My husband is not who he claims.” She laid the papers flat with hands that still trembled.

“These prove he’s been selling off assets and moving money—recording half shipments at full price, listing slaves as dead who were sold, hiding funds under other men’s names.” Her voice lowered.

“He plans to abandon this place.

This marriage.

Once he’s pulled enough through his net.”

Samuel said nothing.

The kitchen shrank around the words until the stove’s bubble sounded too loud.

Outside, a mockingbird sang sunny nonsense into heat.

“Next month,” she said, and he watched her throat work, “he’s arranged to sell most of the house slaves.

Including the children.”

If fear can tilt a floor, the boards pitched then.

He saw his mother forced down a road her ankles could not bear.

He saw his sister’s small hands bleeding on bolls that tore like teeth.

Being sold south was a story with a thousand endings and none of them good.

“Why tell me?” His voice came out steady through a storm.

“Why not your brother-in-law, the sheriff?”

“His brother shares his accounts.

The sheriff shares his whiskey.” She laid a palm on the papers.

“I have no allies in this town.

No family near.

No money he does not count.

I need someone who is always watching and never seen.” Her gaze sharpened.

“You’ve poured tea while men discussed their sins like they were crop prices.

You have been invisible in plain sight.”

Being noticed for his invisibility was a different breed of threat.

“If you help me stop him,” she said, “I will ensure you and your mother are not sold.

And I’ll move your sister to the house.”

Promises.

Words that could be folded into a rope if you grabbed wrong.

He knew he should decline.

He heard the whip in the space between yes and no.

And then he saw his sister’s face and heard his mother’s breath after long stairs and he understood that some refusals were a slow kind of dying.

“All right,” he said.

Relief loosened something in her mouth that might once have been a smile.

“Find his ledger,” she said.

“The real one.

He keeps two sets of books—the show ledger and the truth.

The truth is bound in green leather with a brass lock.

It will look like this.” She pressed a sample into his palm.

The handwriting was Master William’s, slanted and sharp.

Samuel tucked the page under his shirt, where it burned.

Wheels crunched outside on gravel.

Eleanor slapped water on her face and pinched her cheeks into color.

Samuel slid for the servants’ door.

“Samuel,” she said, and he turned.

“If he discovers what we’re doing, he will kill us both.

He already has.” His face gave her the question his mouth did not.

“The previous overseer didn’t die of fever,” she whispered.

“He found something.

The next day he was in a pine box.”

Samuel nodded once.

He left the kitchen with a new map in his head and the powder keg sound of time burning down.

He did not sleep that night.

He lay on straw and listened to the other men breathe while his mind counted risks.

His mother, Esther, watched him rise in the gray before dawn and did not press.

She put her rough, warm hand on his cheek and said the words she had made into a spell over his life: Keep your head down, your ears open, your thoughts hidden.

Trust no one.

At breakfast, Master William announced he’d be gone until evening.

Eleanor said she’d visit neighbors.

Samuel refilled the cups and did not look at her when she passed him in the hall and slipped a small key into his palm.

“Return before sundown,” she murmured.

The key was cold and warmed against his skin.

He completed his tasks to avoid notice.

He stood in the hallway and listened.

The house breathed.

The kitchen clattered.

A maid hummed upstairs, high and soft.

He turned the key in the study door.

It clicked, loud as a bell in his head.

The study smelled like lemon oil and victory.

He moved along shelves and mantels and under furniture.

He traced seams with fingertips.

Where would a man who thought he’d never be caught hide the thing that could catch him? The clock ticked and the window lit dust like a snowfall.

He knelt at the fireplace and felt, with the pads of his fingers, for what the eye couldn’t see.

A lever, small as a lie.

The panel eased open.

He breathed out.

Green leather.

Brass lock.

He held it, felt how heavy truth could be.

Footsteps in the hall.

A shadow slashed the light at the jamb.

The handle turned.

“Mr.

Haynes, Master wants you at the south field,” Isaiah called from the corridor, casual as idle talk.

The handle stilled.

Haynes’s voice, impatient.

A pause.

The steps receded.

Only then did Samuel’s lungs pull air.

He put the ledger back and sealed the panel.

He slipped into the hallway and nearly collided with Abigail.

She narrowed her eyes.

“Cook’s been calling for you,” she said.

When he mumbled an apology about the master’s watch, she caught his arm harder than she needed to and leaned in.

“Whatever game you playing, boy, it ain’t worth your hide.”

That afternoon, Samuel passed Eleanor on the stair with linens in his hands and said, low as breath, “Hidden panel beside the fireplace.

Lever under the mantel.” She said, “Leave the key on my table when you turn down the bed.” He did, tucking it under lace.

He caught the corner of a small leather journal beneath her pillow, a letter peeking in a man’s hand that wasn’t William’s, and looked away on purpose.

He had enough secrets to carry already.

Master returned early and sour, the day’s plans chewing at him.

He drank too much and asked Eleanor about visits she hadn’t paid.

He invited Samuel to bring brandy to the study and shut the door halfway.

“We need to accelerate,” he told Haynes.

“My wife is suspicious.

The buyer from Georgia is eager.

The papers will be ready.” Haynes asked about William’s wife.

“Tragic,” William said, tone bland.

“I doubt she’ll survive summer.”

Samuel knocked, set the tray down, and left his fear pressed flat between his ribs.

Isaiah tapped at the cabin window after midnight and led Samuel to the oak where night shifts its weight.

“You’re playing with fire,” he said without greeting.

“I saw you leave the study.

I saw how the mistress looks at you.

Don’t mistake being seen for being saved.”

“She told me he plans to sell us all next month,” Samuel said.

The words tasted like iron.

“She wants me to find his ledger.

There’s proof.”

“It’s not next month.

It’s next week,” Isaiah said, and watched the knowledge stagger Samuel.

“I heard him down by the press.

Buyers coming early.

Some are thinking of running.”

Running.

The word lit a bright terror.

Samuel had watched what happened to a man who didn’t make it.

“My mother can barely walk,” he said.

“My sister is eight.”

“The old and young slow you down,” Isaiah said, and it was not cruelty.

It was math.

“Sometimes love is a kind of leaving.

You think the mistress will save you? White folks quarrel and use us as weapons.

When they’re done, they drop the blade.” He rolled up his sleeve to a small star-shaped scar.

“There’s a line opening the night after tomorrow.

If you’re coming, you meet us behind the smokehouse when the second dog stops barking.”

Samuel thought of the paper under his mattress.

“I need to see what’s in that ledger,” he said.

“There was a name on one of her papers—J.

Blackwood.”

Isaiah’s face changed almost imperceptibly.

“Jacob Blackwood,” he said.

“Your master’s old partner.

Accused him years back of stealing.

Folks believed Thornfield because people like him wear respectability the way they wear coats.” He looked toward the big house as if he could see the papers behind the panel.

“If the ledger proves anything, it won’t be the law that saves you.

It’ll be leverage.

And when it slips, it’ll slip on your neck first.”

“Then what do I do?” Samuel asked, the world narrowing to the two paths Isaiah had laid at his feet.

“You got one day to decide,” Isaiah said.

“One.

Watch the mistress.

White women’s tears are more dangerous than white men’s whips.

When things fall, they point at the nearest black body and say, ‘He did it.’”

Back in the cabin, Esther was awake.

“Haynes was here,” she said.

“Asking if you can read.

Asking about you and the mistress.” Samuel said nothing and took his mother’s hands.

“He’s selling us next week,” he said.

“Isaiah says there’s a way out the night after tomorrow.” She considered, then nodded as if adjusting a plan for baking instead of running.

“My legs won’t carry me,” she said.

“You take your sister and go.”

“I’m not leaving you,” he said.

She cupped his face.

“Then you find a different door.”

Morning came crimson.

William said he’d be in town arranging matters.

Eleanor handed Samuel a pass and a sealed envelope without an address.

“To Mr.

Patterson at the post,” she said.

“And be careful.”

In town, the postmaster took the letter and slipped it into a drawer like a habit.

At the general store, Samuel asked cautiously after Blackwood and learned he lived near the state line.

Outside the courthouse, a man nailed up a notice: Auction, Property of William Thornfield, to be held at Thornfield Plantation, Tuesday next.

Men laughed about delicate northern wives drifting conveniently into fever.

Samuel stood and swallowed heat.

Haynes pinned him by the shoulder.

“Pass?” he asked.

He took it, read it, pocketed it.

“Asking about Blackwood, were you?” he said, and there was satisfaction in his mouth.

“Mrs.

Miller knows her duty.”

“Actually, Mr.

Haynes,” said a voice behind him, cool as spring water, “you’ll find the pass in order.” The man’s coat fit like a second self.

His cane had a gold head.

His hair was silver and expensive.

Haynes’s posture faltered.

“Mr.

Blackwood,” he muttered.

“This isn’t your concern.”

Blackwood extended a hand.

“It is when a citizen’s treated unfairly,” he said, and the word citizen sat in the air and dared anyone to challenge it.

He gave the pass back to Samuel.

Haynes slunk away, promising watchfulness.

Samuel turned gratitude into a risk.

“Sir,” he said low.

“We may have a mutual enemy.”

“Say it, boy,” Blackwood replied.

“Mistress Eleanor found a ledger,” Samuel said.

“Proof.

She sent me with a letter.

She…she wants justice.

So do I.”

Blackwood’s expression slipped for a breath at her name.

He nodded once.

“Tell her I received it.

Tell her old debts will be settled.” He tapped away.

Back at Thornfield, buyers’ voices swelled in the study.

“Turn around,” one of them said to Samuel when he brought the tray.

“Let me see your build.” William sold him and his mother with a sip of brandy and a laugh.

Eighteen hundred dollars, delivery after papers.

The smile Samuel walked away with was not a thing his face felt.

He found his mother and told her everything.

“Run,” she said simply.

“Take your sister.” He shook his head.

“If that book is what I think, it’s worth more than any price he put on us.” Esther’s eyes, tired and fierce, gave him both permission and warning.

He needed the ledger now, not at midnight.

There was a narrow passage behind the wardrobe in the master bedroom he’d dusted once, a seam in the paneling he’d mapped in his mind.

He slid into the slit of space.

Through a crack, he watched William show the buyers down the columns of fake books.

When their backs turned, Samuel eased through the passage, felt for the lever, opened the compartment, and withdrew green leather and, beneath it, a folded paper someone had tucked and forgotten.

He fled to the smokehouse, the only space no one used in summer’s heat.

He lit a stump of candle and opened the book.

The numbers told a story even his limited reading could follow.

Money in, money out, money diverted—names in the margin that matched facades in town.

Eleanor’s family trust drained steadily for years.

Payments to an J.

Blackwood crossed out and turned to losses.

A pattern of half shipments billed whole.

Sums moved through Charleston to New York to London.

And, wedged under the ledger where habit had hidden it, a letter in a script that wasn’t William’s: Eleanor’s, to “My dearest J.”

He read enough to understand.

She and Blackwood.

The ledger used to prove Blackwood’s innocence, to break William’s facade and free Eleanor from a marriage that had been profit, not love.

She wrote about justice.

She wrote about money due.

She did not write about the people sold as property under the math.

Isaiah’s warning rang in Samuel’s ribs.

You’re a shield.

When it falls, she’ll hold you up to the blow.

Voices cut into the smokehouse’s silence, his name carried on them.

He snuffed the candle, slid ledger and letter into a crack in the wall behind old hooks, and stepped out into light.

“Eleven o’clock,” Abigail said when she found him.

“Mistress wants you.” Her mouth was a tight line.

“Haynes has been asking where you went in town.”

Eleanor stood at her window, hands white at the sill.

“Did you deliver the letter?” she asked.

“He received it,” Samuel said.

“He told me to tell you old debts will be settled.”

She turned, and for an instant something that wasn’t calculation moved through her face—fear or hope, he couldn’t tell.

“The buyers arrived early,” she said.

“We are running out of time.

I need that ledger tonight.”

William opened the door without knocking.

“Come,” he said.

“They want a closer look.”

The buyers handled Samuel like goods they assumed the right to inspect.

They talked about his shoulders, his teeth, the price he’d fetch beside a piano.

They bought him and his mother with a laugh and a pledge.

“We’ll sign this evening,” William said.

“My wife will not be present,” he added, tone wry.

Samuel carried the ledger’s weight in his mind back to his mother.

“I saw enough,” he told her.

“It’s all there.

Names, numbers.

The truth.

And something else.” He swallowed.

“She’s writing to Blackwood like a woman writes to a man she needs for more than law.”

Esther pushed her hair back with her wrist and looked at her son.

“Then you don’t trust her,” she said, not a question.

“I think she wants out,” he said.

“I think she’ll use whatever she has to get it.”

“But can you use what she has to get what we need?” Esther asked, and there was the plan she had framed without ledger or letter.

Isaiah stood in the doorway of the smokehouse in the dark and held the candle while Samuel pulled the ledger from the crack.

“You sure?” Isaiah asked.

“This is the kind of truth men kill to keep quiet.”

“They already have,” Samuel said.

“They plan to again.”

At first light, he walked down the road to town with the ledger under his shirt and risk braided into every step.

He waited until Blackwood passed the post office.

“Sir,” he said.

“I have something you want.” He led the man to the shade of an oak and set the ledger in his hands.

Blackwood opened it and read for the space it takes a bird to cross a field.

His face did not change much and what it did show was not triumph.

It was something like grief folded into relief.

“Is this all?” Blackwood asked.

Samuel held up the letter.

“Enough to ruin him in his own house,” he said.

“Enough to free you from a lie and her from a marriage.

Not enough, maybe, to free us.”

“What do you want?” Blackwood asked, and there the world split to his advantage.

“My mother and sister,” Samuel said.

“And anyone else I can add without breaking the rope.

Not papers some court can undo with a smirk.

Real tickets north, money for the road, places to wait where hands don’t reach.”

Blackwood weighed the book and the boy and did a thing Master William never once did: he told the truth he could.

“I can pull him down,” he said.

“I can embarrass him, bankrupt him, perhaps get him charged by men above your sheriff’s reach.

I can get ten people out without the net closing.

Beyond that, I make promises I cannot keep.”

“Then give me ten,” Samuel said.

“Today.”

“Tonight,” Blackwood said.

“After his dinner.

After he raises a glass to the life he thinks he has left.

Bring your people to the cooperage.

There is a wagon leaving at midnight.

There will be a diversion.

You will move in the space where men blink.”

When Samuel returned, the house felt like a mouth of a trap.

Buyers laughed in the study.

Papers rustled.

William enjoyed his own performance.

Eleanor stood at the top of the stairs with her hand on the rail, jaw clenched.

For a heartbeat, their eyes met.

He did not tell her about the ledger or the letter.

He did not tell her about Blackwood or the wagon.

He did not tell her she had not been entirely wrong about him—he had been the one she could not see until she could.

He simply moved through the house like a sound you hear and cannot place.

He told Isaiah.

He told Esther.

He told the women with small children and men with scars that wouldn’t take another lash.

They did not tell anyone else.

A plan that saved some by necessity will always feel like betrayal to those left on the ground, and this was a place where guilt was built into the walls.

He knew it would live in him regardless.

At dinner, William toasted profits.

He spoke of “Changes to come” and smiled at men who thought themselves wolves.

In the kitchen, Cook burned a pot deliberately and cursed loud enough to draw the house into the hubbub.

In the study, a curtain caught fire and filled the hall with smoke.

People shouted and carried pitchers and buckets and righteousness.

In the confusion, doors stood wide.

In the yard, dogs barked twice and then lay down, lulled by meat soaked in sleeping draught.

In the cooperage, Pike lifted a loose board and made space where there had been none.

In the wagon, Samuel lifted his mother by the elbows and put her squarely into a place no one had ever saved for her before.

He hoisted his sister and felt the small fierce clutch of her arms.

He counted faces.

Nine.

He turned back once to the doorway, looked for Isaiah.

Isaiah stepped from the dark, eyes steady.

Ten.

“Go,” Isaiah said to him.

“Don’t look back.”

Samuel nodded.

He looked back anyway at Eleanor’s window.

A candle burned there for a beat and went out.

He did not know what that darkness meant.

He did not know if she had helped or merely not stopped.

He did not know if she would live through the weeks ahead.

He did not know if Blackwood would keep his word beyond the night.

He did know the road under the wagon wheels felt like something he had not yet allowed himself to name: beginning.

The town woke to scandal.

A ledger arrived on a judge’s desk with a letter attached and a cover note bearing a name nobody dared ignore.

Men who had shaken William’s hand looked at their palms and scrubbed them on their coats.

The auction notice came down from the board with new hands.

The sheriff knocked at a door and found no one home.

A pastor adjusted a sermon he had already preached a dozen times and found he could no longer bear the sound of his own certainty.

In the space where law had not yet moved, a wagon rolled across a field under a moon that looked like a coin cut in half and offered to no one in particular.

Samuel sat with his mother’s hand inside his and his sister’s head against his shoulder and felt the trembling in both.

He listened to the creak of axles and the low murmur of men who had watched too many nights turn against them.

He thought about the kitchen where a woman had cried and asked a boy if he could read.

He thought about the way a page sounds when you turn it and everything that happens next is different.

By the time the sun rose over a river none of them had seen free, they had made it far enough to be worth whispering about.

The road ahead was long, and freedom in America was a word with splinters in it.

But they were moving.

In a world built on fear, ten people had placed their weight on courage instead, and the weight held.

News

The Profane Secret of the Banker’s Wife: Every Night She Retired With 2 Slaves to the Carriage House

In a river city where money is inked but paid in human lives, the banker’s wife lights a different fire…

The Plantation Lady Who Locked Her Husband with the Slaves — The Revenge That Ended the Carters

The night I decided my husband would go to sleep on a slave’s pallet, the air over Carter Plantation felt…

The Pastor’s Wife Admitted Four Women Shared One Slave in Secret — Their Pact Broke the Church, 1848

They found her words in a box that should have turned to dust. The church sat on the roadside like…

The Paralyzed Heiress Given To The Literate Slave—Their Pact Shamed The Entire County, Virginia 1853

On the night the county gathered to watch a girl be given away like broken furniture, the air over Ravenswood…

The Judge’s Daughter Who Secretly Married Her Father’s Favorite Slave—The Trial That Followed, 1851

They said the courthouse had never held so many people. The air felt like wet wool—heavy with perfume, sweat, and…

The Plantation Lady Replaced Her Husband’s Heir With the Cook’s Slave Child—Georgia’s Silent Scandal

They say the storm that broke over Merryweather Plantation in the spring of 1854 was the worst anyone in that…

End of content

No more pages to load