The iron bell of the auction house clanged through the humid air of Natchez, Mississippi, on a blistering July afternoon in 1851.

Its metallic cry sliced the market’s chatter, turning heads toward the wooden platform where human lives were weighed against coin and sold like cattle.

Among planters, merchants, and speculators stood a man whose posture didn’t match the mood.

His name was Thomas Whitmore.

He was thirty-two, tall, lean, prematurely gray at the temples.

He wore a plain black suit and a set jaw.

If the others held the weird calm of people who’d trained themselves not to see, Thomas held the look of someone who couldn’t stop seeing.

He had inherited Riverside—land, house, and seventy enslaved people—two years prior.\

The property lay fifteen miles north, modest by the county’s standards.

The inheritance was both blessing and curse.

In his youth, Thomas had studied at a Quaker school in Pennsylvania, reading abolitionist pamphlets and hearing slavery named the great sin of the republic.

Theory stiffens conscience.

But theory doesn’t pay debts.

When his father died, Thomas returned to Mississippi, trapped between the laws he lived under and the moral world he believed in.

He tried to run Riverside differently.

No whips.

Small wages people could save.

Families kept intact.

Better food and cabins with floors and proper chimneys.

He knew it was still wrong.

He owned human beings.

His gestures were drops of mercy in an ocean of violence.

He slept poorly.

He hadn’t come to town to expand his holdings.

He came because his overseer, Daniels—a man Thomas had never fully trusted—brought him a rumor.

Three sisters from a bankrupt estate would be sold that morning, and Cyrus Blackwood intended to buy them.

Blackwood ran the “fancy” trade, feeding New Orleans and Mobile’s hidden markets: young women, “untouched,” sold as concubines to wealthy men who paid for both secrecy and impunity.

Legal enough.

Rotten enough to make even regular slaveholders look away.

“If you mean to stop it, you’ll need money in hand,” Daniels said, voice oddly tight for a man who laughed at pain.

Thomas spent the night pacing his study.

Buying people to keep them from Blackwood was still buying people.

He would become the very thing he hated yet again.

But letting them be sold into a particular hell, doing nothing—was that better? At dawn, he made a decision he didn’t like.

He’d purchase if he had to.

Then he would find a way, however slow, to get them free.

He stood in the crowd as Simmons, the red-faced auctioneer, worked the square.

Two dozen field hands sold.

Children split from their parents while mothers’ screams turned thin in the heat.

Thomas kept his place.

Finally, Simmons announced the sisters.

“Three prime young females, lately from the Ashford estate.

Healthy, strong, and”—he paused, enjoying the attention—“certified untouched.

Suitable for housework or gentlemen with more particular interests.”

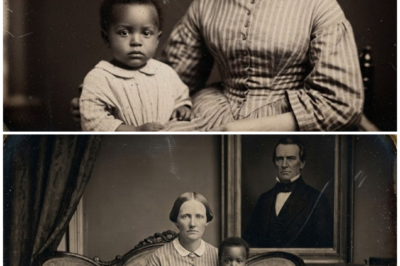

The eldest looked twenty-three, dark-skinned, composed by force.

The middle perhaps twenty-one, lighter, trembling but upright.

The youngest—eighteen, clutching a cloth bundle—cried without sound, as if the voice were gone and only tears remained.

Bidding began.

Eight hundred.

Nine.

Blackwood raised a gloved hand.

“Twelve hundred.” The crowd murmured.

Thomas felt his stomach turn.

His breath shortened.

He had brought fifteen hundred—supply money he couldn’t afford to spend.

He spoke anyway.

“Fifteen hundred.” The words were steady.

Heads turned.

Blackwood’s eyes found him, narrowed, then hardened.

People knew them both.

Thomas was the odd planter with “Northern notions.” Blackwood was what he was: a predator well-dressed.

“Sixteen hundred,” Blackwood said, jaw tight.

Thomas had hit his limit.

He had nothing beyond what he’d promised himself.

He swallowed and took one more step over the edge.

“Seventeen hundred,” he said, “payable in gold within the hour.”

The square erupted in noise.

For domestic workers, seventeen hundred was absurd.

For bodies destined for the fancy trade, it was how a man like Blackwood made profit vanish.

He started to raise his hand again, but his accountant touched his sleeve—a small shake of the head.

The numbers didn’t work anymore.

Simmons slammed the gavel.

“Sold to Mr.

Thomas Whitmore for $1,700.”

Thomas pushed through the heat toward the platform.

The sisters watched his approach with the practiced suspicion of people who know a man’s smile is too often a blade.

In slavery, kindness is a prelude to harm.

He stopped before them and spoke to them, not to Simmons.

“My name is Thomas Whitmore,” he said quietly.

“You will come to my plantation, Riverside.

I give you my word you will not be harmed there.”

The eldest’s eyes—Clara, as Simmons had named her—read his face the way one reads a sky for weather.

She said nothing.

She gave a small nod that meant only: I heard you.

Thomas told Simmons he’d return with the money and that until then no one was to touch the women.

“If anyone does,” he said, “the sale is void.” Simmons liked commissions.

He agreed.

Forty-five minutes later, Thomas brought the pouch of coins.

Gold clinked on the office table.

Papers were signed.

Chains were removed.

He saw the red marks their iron had left on skin.

He gestured toward his wagon—a simple “please” that drew odd looks.

Enslaved people weren’t asked.

They climbed in, close together, shoulders braced as if expecting to be struck.

He took the reins and guided the horses out of Natchez, feeling Blackwood’s gaze between his shoulder blades all the way to the river road.

They reached Riverside three hours later, dust in their hair and fear in their chests.

The house was plain white wood with a wraparound porch.

Outbuildings behind.

Cabins farther back.

Thomas saw it through their eyes and felt shame.

On the porch stood Esther—the household manager, enslaved at Riverside for forty years, the woman who had raised Thomas after his mother died.

She took in the wagon and the faces, and her brows lifted just enough to register surprise.

Thomas asked for guest rooms in the main house.

Esther nodded and disappeared to prepare them.

The sisters exchanged looks.

Guests? In the main house? Fear sharpened confusion.

Thomas helped them down.

Even that gesture felt wrong because they knew how often “helping hands” became hands that didn’t ask.

“I know you have no reason to trust me,” Thomas said.

“You were bought and sold.

I can’t erase that.

I didn’t purchase you to exploit you.

I purchased you to prevent Cyrus Blackwood from doing so.”

“Why?” the middle sister—Hannah—asked, voice thin but steady.

“Because three years ago,” Thomas said, “I watched my father die.

He begged me to forgive him for the way he lived, for owning people, for knowing it was wrong and doing nothing.

I promised him I would do better.

I can’t legally free you today; Mississippi law would force you out within thirty days and return you to chains if you stayed.

But I can treat you as human beings while I work the law and build a path north.

It will take time.

That is my intention.”

“You expect us to believe that?” the youngest—Ruth—asked, strength surprising even her sisters.

“You paid seventeen hundred out of pure goodness?”

“No,” Thomas said.

“I expect you to judge me by what I do next.”

Esther prepared rooms upstairs: real beds, clean linens, a basin and pitcher, a small wardrobe, curtains at the window.

Luxury doesn’t always comfort.

Sometimes it frightens.

They stood in Clara’s room—largest of the three—and waited for whatever came next.

Ruth collapsed into sobs that shook the bed.

Hannah held her tight.

Clara kept standing, fists clenched, voice a low wire.

“We face it together,” she said.

“Whatever it is.”

Esther returned with clothing.

“They were Mrs.

Whitmore’s,” she said.

“Take what you need.” Clara looked into Esther’s face, seeing time lines and weather.

“Is he what he seems?”

“Forty-two years,” Esther said.

“I’ve seen three generations.

Mr.

Thomas is not like his father or grandfather.

He tries to treat people better.

But he still owns people, including me.

Kindness doesn’t erase that.

He is not cruel.

He is conflicted.

That’s the truth.”

Dinner was a shock.

They sat at a table with a man who owned them and ate the same food he ate.

He stood when they entered, indicating chairs as if they were guests.

He asked careful questions.

They gave careful answers.

Night brought creaks, footsteps, fear.

No one came to their doors.

Days formed a pattern unlike anything they’d known.

Esther gave light tasks.

Thomas kept distance.

He appeared at supper, spoke briefly, and left them be.

Slowly, curiosity overcame the rigid silence of survival.

“How will you free us?” Hannah asked one evening.

Thomas explained the cruel arithmetic of Mississippi manumission: how freed people had to flee the state within thirty days or be arrested, how most northern places offered scant protection, how the path required a community ready to receive, money to start, and trusted hands along a route.

“So we can never be free?” Clara asked, anger under control but present.

“You can,” he said.

“But paper isn’t enough.

It requires place, funds, people.

I’m working with Quakers in Indiana and Ohio.

I’m trying to save enough to give a stake.

It is slow.”

Ruth asked the question no one wanted to ask.

“Why do you care?”

“Because Esther raised me,” Thomas said.

“Because I first loved the face of an enslaved woman and thought that was normal.

Because I went north and saw equals.

Because my father died asking a forgiveness he hadn’t earned.

I am trying to act before I am old and cowardly.

I am trying to be less of a coward now.”

Clara’s reply was stripped of politeness.

“We did not ask to be instruments of your redemption,” she said.

“We didn’t ask to be bought so you could feel better.

We wanted to be left alone, living lives not owned.”

“You’re right,” Thomas said.

“I won’t apologize for stopping Blackwood.

But you are right: much of this is about my conscience.

That’s its own selfishness.”

Lines shifted.

The sisters tested boundaries.

Hannah asked to see the accounts and ended up learning bookkeeping.

Ruth asked for books and found a study with shelves open to her.

She also found a journal where Thomas interrogated himself in ink—copying abolitionist and apologist arguments, trying to reconcile them, failing, asking the question that mattered: How many years will I steal from seventy lives before I find the courage to act?

Clara asked to see how the rest of Riverside lived.

Esther walked her to the cabins.

They were better than most—floors, chimneys, food in the pot—but they were still proof of a system that made people property.

Wages went to shoes and little else.

Fear lived even under mercy.

“It’s a prettier cage,” Clara told her sisters.

“Better than most still means trapped.”

Spring turned to summer.

A strange alliance grew between three sisters and a man who used the word “owner” like a thorn in his mouth.

Then Cyrus Blackwood remembered how humiliation tasted and decided to make Thomas eat it.

Rumors spread.

Shooting.

Fire.

Credit withdrawn.

Buyers refusing fair prices.

By August, Thomas was being strangled by a network that kept plantations alive.

It was polite in public and vicious in private.

“You cannot keep doing this,” Clara told him, finding him bent over a ledger, debts climbing like vines.

“You’re destroying yourself.”

“What would you have me do?” Thomas asked.

“Sell you back? Pay my debts with your lives?”

“Be smart,” Clara said.

“You’re trying to save everyone at once.

Start smaller.

Build a path.

Let people choose to walk it.

Some will go first.

Others will wait.

Make it a route, not a miracle.”

Hannah added the structure.

“Explain the risks.

Let people decide.

Don’t choose for them.”

Ruth said what the plan required.

“Start with us.”

Thomas wrote letters in code.

Replies came hidden in shipments, lemon-ink instructions revealed by heat.

He turned assets into coin.

He bought travel clothes and sewed gold into hems.

He spoke quietly to those who might go.

Twelve volunteered: Clara, Hannah, Ruth; Samuel, who dreamed of finding a wife sold to Louisiana; Isaac and Benjamin, brothers without family; Patience, a midwife and healer with steel in her voice; Abigail, teenage and alone since winter; three others with stories woven from grief and hope.

He laid out a map in the barn.

“Night travel.

Day hiding,” he said.

“North through Mississippi into Tennessee.

Patrollers are thick.

Contacts there will feed you and guide you.

Then conductors to Kentucky and Indiana.

Three to six weeks.”

“What if we’re caught?” Samuel asked.

“Then you will be returned and likely sold,” Thomas said, truth and weight in the same breath.

“I cannot protect you.

If you go, it’s because freedom is worth the risk.”

Patience rested her palm on the table, fingers scarred by years.

“If I have one day free before I die,” she said, “it’s worth it.”

They left on a moonless September night, in pairs and trios, slipping through the pines to a rendezvous three miles out.

Thomas handed each a small bag: food, water, blanket, coins.

He pressed letters to Clara’s hand—names and places that meant safety if reached.

“Be safe,” he said, inadequate words for an inadequate world.

“Thank you,” Clara said, a leader’s blessing for a flawed man trying to be less flawed.

He waited.

Two weeks later, a message arrived from Tennessee.

“Package received.

All goods acceptable.

Moving to next station.” Three weeks after that: “Package delivered to final destination.” All twelve made it.

Thomas wept in his study, relief and grief folded together like paper, and understood he had stepped from contemplation into action.

Word seeped through Riverside, and people who had resigned themselves to slavery began to think in terms of routes and nights.

He planned to wait before sending another group.

Blackwood planned to make sure there wouldn’t be one.

He bribed officials, followed correspondence, threatened merchants.

By November, he had assembled enough suggestion to convince a friendly sheriff to move.

The warrant arrived at Thomas’s door.

Sheriff Morrison, Cyrus Blackwood standing behind him like a shadow that smelled of cologne.

“Aiding fugitive slaves,” the sheriff said.

“You will come.”

Thomas went.

The jail stank of sweat and despair.

His lawyer, Anderson, suggested denial.

“Argue that they ran on their own,” he said.

“Claim the letters were philosophical, not practical.”

“I won’t lie,” Thomas said.

“If I go to prison, let it be for helping people, not hiding from myself.”

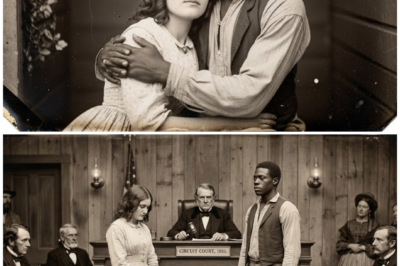

The trial in January 1852 drew a crowd.

The prosecutor—Carlisle—painted Thomas as a radical undermining the South.

Letters.

accounts.

strangers on roads.

The fancy-auction rescue.

It was a tapestry of circumstantial evidence woven thick enough to feel like proof.

Then a door opened, and Esther walked in with two dozen people from Riverside.

The judge frowned.

The prosecutor protested.

The law allowed enslaved people to testify for their master.

Esther took the stand with the bearing of someone who has seen too much and refuses to lie anymore.

“I raised Thomas Whitmore,” she said.

“I watched him try to be good in a foul system.

I don’t know if he helped those twelve.

I do know he treated people with dignity and gave them hope.

If they ran, maybe it’s because he taught them to believe freedom was possible.

If he helped them, he chose humanity over law.”

Others spoke, one after another, about small mercies and refused violence.

The jury returned with a compromise: guilty on the technical charge, leniency recommended.

Judge Whitfield sentenced Thomas to one year in county jail and a $1,000 fine.

It should have ended there—with his property seized, Riverside liquidated, and Blackwood waiting to scoop up lives.

But Riverside’s people, led by Esther, did something the law didn’t foresee.

They passed the hat.

Small wages saved, pennies scraped.

They asked free Black tradesmen who knew Thomas as fair.

They wrote north to Quakers who had received the twelve and asked for help.

Together, they raised money for the fine and bought at auction as many people as they could to prevent their sale to strangers.

It wasn’t enough to save everyone.

It was enough to prove that solidarity lives where the state pretends it does not.

Thomas served his year.

Blackwood bought Riverside cheap.

When Thomas walked out of jail in January 1853, he owned nothing and wore the brand “criminal” in a place where even kindness is criminal when given to the wrong people.

Waiting for him were Esther, several who had been freed through northern purchase, and a letter from Indiana.

Clara wrote it.

“We have land,” the letter said.

“We have work.

We have freedom.

This isn’t your redemption.

It’s our lives.

But there is room.

Come.”

He went north slowly, working odd jobs, arriving in summer to find a community built by people who had refused to stay property.

Clara, Hannah, and Ruth farmed adjoining plots.

Samuel had found his wife.

Patience delivered babies into a world that could finally call them free.

They helped others along the same route.

Thomas taught reading and sums by day and coordinated escapes by night.

Before the Civil War broke slavery, he helped over three hundred people reach freedom.

He never regained wealth.

He gained something better.

He slept.

He stayed close to the sisters who started it all.

They never let him mistake their lives for his story.

“You are not our savior,” Clara told him more than once.

“You’re a man who tried.

We saved ourselves with your help.” He nodded and kept working.

He died in 1889, seventy years old, buried in a small plot near a school he had helped build.

Hundreds filled the service.

Clara, gray now, spoke over his grave.

“Thomas Whitmore was born into an evil system and stayed in it too long,” she said.

“He did not save us.

We saved ourselves with his help.

But he looked at wrong and named it.

Then he chose action over comfort until it cost him everything.

That doesn’t make him a hero.

It makes him human.

In a world that rewards cruelty and punishes compassion, that matters.”

Hannah became a teacher, schooling children whose first letters were their own names written freely.

Ruth became a writer, recording stories of escapes and nights and the hands that made freedom possible.

Clara became a community leader—organizing, advocating, turning arrivals into neighbors.

They never forgot the auction’s bell or the first bed in the main house or the hard, dark road north.

They remembered people who chose to resist and paid for it, and they remembered how choices shape systems.

Slavery depended on white people selecting indifference or cruelty.

When enough chose otherwise, cracks appeared.

Thomas’s story didn’t end with the neat, noble victory he might have dreamed at the Natchez block.

He went to jail, lost his land, and left home.

He helped hundreds find freedom.

He helped build a place where dignity lived.

He proved that imperfect moral courage—the kind that bleeds and fails and keeps going—can change lives.

That’s what shocked his neighbors: he bought three enslaved girls and didn’t do what was expected.

He treated them as people.

He worked toward their freedom.

Then he let their freedom change him, accepting losses almost no one in his position would accept—and joining the larger, quieter story of resistance that ran beneath the South’s official narrative like a river carving stone.

News

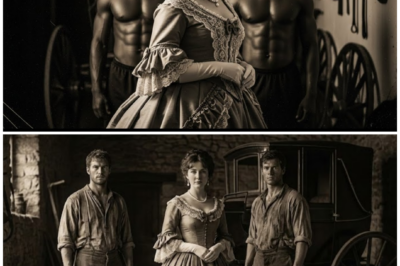

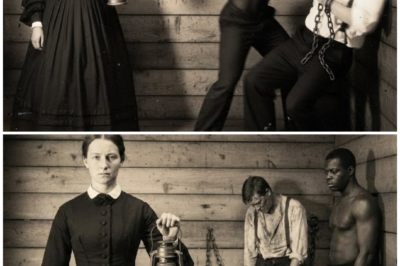

The Profane Secret of the Banker’s Wife: Every Night She Retired With 2 Slaves to the Carriage House

In a river city where money is inked but paid in human lives, the banker’s wife lights a different fire…

The Plantation Lady Who Locked Her Husband with the Slaves — The Revenge That Ended the Carters

The night I decided my husband would go to sleep on a slave’s pallet, the air over Carter Plantation felt…

The Pastor’s Wife Admitted Four Women Shared One Slave in Secret — Their Pact Broke the Church, 1848

They found her words in a box that should have turned to dust. The church sat on the roadside like…

The Paralyzed Heiress Given To The Literate Slave—Their Pact Shamed The Entire County, Virginia 1853

On the night the county gathered to watch a girl be given away like broken furniture, the air over Ravenswood…

The Judge’s Daughter Who Secretly Married Her Father’s Favorite Slave—The Trial That Followed, 1851

They said the courthouse had never held so many people. The air felt like wet wool—heavy with perfume, sweat, and…

The Plantation Lady Replaced Her Husband’s Heir With the Cook’s Slave Child—Georgia’s Silent Scandal

They say the storm that broke over Merryweather Plantation in the spring of 1854 was the worst anyone in that…

End of content

No more pages to load