Seven men stepped off the road and into the timberline on September 23, 1861.

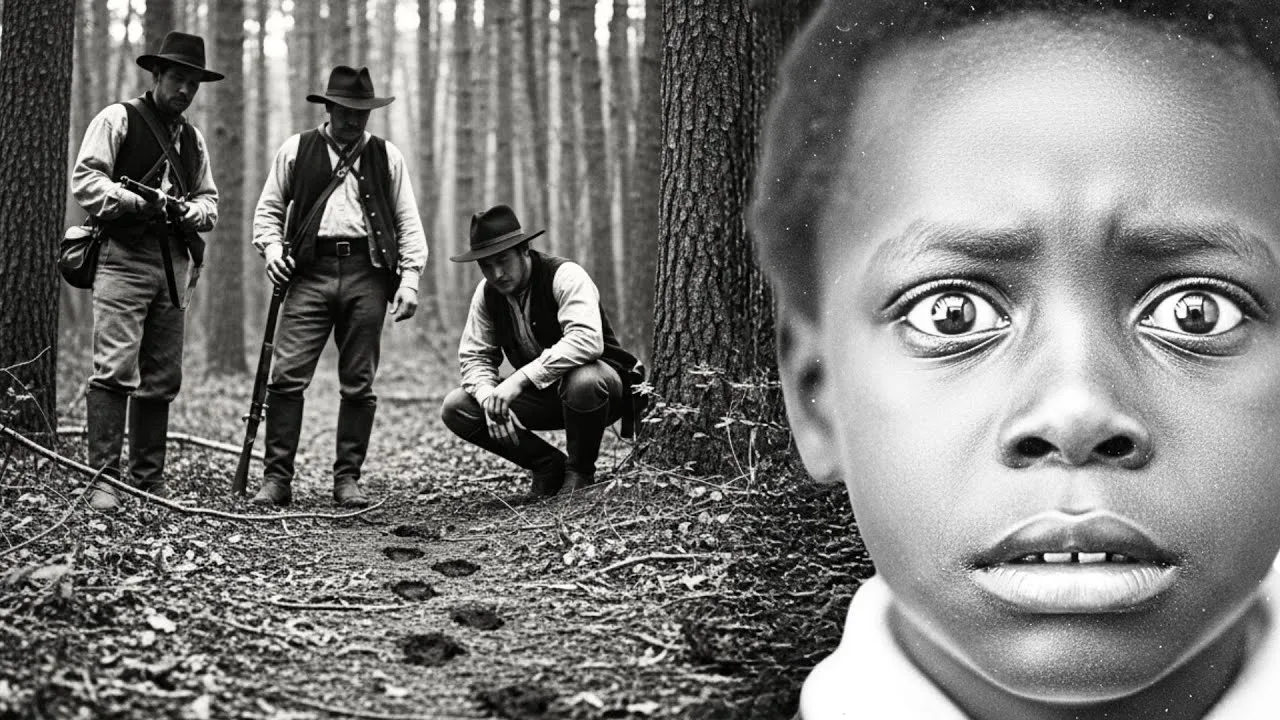

Lanterns swung in humid arcs.

Rifles settled against shoulders.

They were not hunting deer or boar.

They were hunting a child—a nine-year-old enslaved boy who had vanished three days earlier from Hollow Pines plantation in central Louisiana.

The planter, Edmund Tarrow, wanted him back.

Not for labor, not for skill, but for the principle: property does not walk away.

On the quarters, the boy had no spoken name.

They called him Silence because he never used words—never a cry, never a laugh, never even a hum.

His eyes were pale and unblinking, an unsettling contrast to his skin—eyes like broken glass, enough to make grown men look away.

Samuel Vickers led the party.

He was nearing sixty, his face leathered and creased by sun and habit.

His hands had gripped more runaways than he had numbers for.

He knew every crossing in that parish, every dry ridge and swamp cut, every trick a desperate person tried.

His father had overseen a plantation.

Samuel had learned early that some people were counted and others were priced, and he had built a life by treating that difference as the truth of the world.

Beside him walked Thomas Harlow, red-bearded and sharp with meanness that leaked into everything he did.

He had come down from Virginia five years earlier, drawn by money in runaway chases.

He was fast—quiet when quiet got results, loud when loud did.

He kept tally in a small notebook: forty-three captures in five years.

Numbers as proof of worth.

Caleb and Jacob Moss—the brothers—joined because the hunt pleased them.

Their father had been a supervisor until he drowned in the Atchafalaya under circumstances nobody discussed.

The brothers were thick-shouldered and heavy-handed.

They didn’t talk to anyone but each other and had a simple method: Caleb circled left, Jacob right, and the middle had nowhere to go.

Robert Whitaker kept to himself.

He might have been thirty-five; he might have been forty.

He had arrived in Lafayette Parish seven years ago and taken tracking work.

He could read a scuffed bark, a bent blade, the directional bias of moss.

He could follow a three-day trail through rain.

He did not say how he learned.

He did not say where he was from.

He did not say anything that wasn’t required.

Nathaniel Cross carried a Bible he never opened.

He was thin and narrow-faced, always dressed like a mourner.

He quoted pieces of scripture when it suited—servants obeying masters, order, hierarchy—as if the work were sanctified.

Righteousness made cruelty more comfortable.

Elijah Thorne was nineteen and eager for hardness.

This was his third hunt.

The first two had been simple—older bodies that could not outrun a boy with a rope and a gun.

This one was different: a silent child they muttered about, not quite human in the way fear makes stories.

They entered the old forest where the canopy strangled daylight.

This stand had existed longer than the town, longer than the plantation, longer than the parceling of land itself.

Oaks thick as courthouse pillars leaned next to cypress shouldering water.

Leaves layered the ground like a long, slow snowfall.

The air carried rot and river-lingering heat.

Somewhere a creek turned muddy.

In the deep, there were no owls, no insects’ chatter, no wind.

Only breath and the scrunch of boots.

Samuel had hunted this timber dozens of times and knew every light gap.

As they walked, the trees felt unfamiliar, the spacing strange.

The air cooled at once, lifting the hair on his arms.

Then—at the border of a clearing where he had stood a dozen times before—Samuel stopped.

There was a house.

There had never been a house.

He would have remembered.

Anyone would have.

But there it stood, a structure of dark, swollen boards, the kind of wood that looks both wet and bone-dry at once.

The windows were narrow slits boarded from within; nail tips rusted through.

The roof tilting as if the builder didn’t care whether gravity had the last word.

Thomas approached and touched the wall.

It was cold—wrongly cold for September in Louisiana.

He pulled his hand back with a reflex and wiped it on his pants.

“Anyone seen this place?” His voice came less confident than he intended.

No one answered.

The Moss brothers moved to either side, peering for glass or gaps.

There were no panes, only boards and shadow.

They pressed faces to seams and saw only dark—the kind that eats light rather than inside-out night.

“How’d we walk past this and not see it?” Jacob asked.

Samuel circled the structure slowly.

No prints in the dirt.

No scuffs in the leaves.

No sign of recent use.

Yet the certainty settled in his chest like a weight.

The boy was inside.

The house felt patient—the way an animal breathes in sleep, waiting for a moment to open its eyes.

“We’re going in,” Samuel said.

Leadership requires decisions spoken like facts.

The iron handle rusted around a hole where palms had pulled.

Thomas gripped it and tugged.

The door opened soundlessly, not sticking, not complaining, despite hinges red as blood.

Lantern light should have flowed past the threshold; it met a darkness that stopped it.

Samuel stepped first.

The temperature fell twenty degrees.

He fogged the air with breath.

The others followed—one by one—raising light, clutching rifles.

Inside was wrong immediately.

The room stretched too long for the footprint they’d seen outside.

The ceiling sat low, beams thick as tree trunks.

Dust coated the floor in uneven waves—disturbance patterns and track-like marks threaded through it.

The walls swallowed each flame.

When Thomas turned his wick up, his lantern guttered and died; when he relit it, the flame flickered and went out in seconds, as if air was food the house refused to share.

Words carved into wood caught the dim.

Not painted, not ink—scratched into planks with metal or glass.

Every surface carried marks: English, Spanish, script no one knew, loops and slashes like prayers, characters whose angles spoke of Africa, of older places.

Names everywhere.

Names beside dates.

Floor to ceiling, post to post.

“These are names,” Jacob said, and his finger traced letters like he might cut himself on the grooves.

“All names.”

Samuel brought his lantern close and found old years he remembered: 1849, 1851, 1856.

Peter: disappeared, rumored North.

Elizabeth: found in the river, story told as drowning while running.

Moses: never found.

Names called into quarters at night; names whispered over smoldering cooking fires with woeful hope or acceptance.

Names etched in wood like a memorial, or a ledger, or a vow.

Thomas slid his notebook from his vest with fingers that shook.

He found three matches between his tally and these walls—people he’d chased, people he’d assumed lost to swamp or broken toward freedom.

Their names lived here.

From beneath the floorboards came breath—slow, steady, deliberate.

Not one chestful, many.

A dozen lungs, maybe more, breathing in perfect rhythm.

Robert went to a knee and pressed his ear to the boards.

The sound vibrated up through wood.

He stood quickly, backing away.

“There’s something under us,” he said.

Nathaniel found a hatch buried under straw and dirt placed carefully, as if someone intended not to hide it so much as let it be discovered in time.

A wooden square with an iron ring.

Samuel and Caleb hauled it open.

The weight was heavy beyond size, as if gravity remembered things humans forgot.

Rust-rot breath washed up—wet earth, iron, meat gone wrong.

Wooden stairs fell into the dark.

The breathing intensified, nearer, yet not particular.

Samuel put a boot on the first step.

The board was soft—spongy.

He descended.

The line followed—single file.

The stairs ran longer than any architecture should have permitted.

Thirty feet down, or felt like it.

Dirt walls braced by beams carved with the same symbols.

Names continued along the descent—lines of letters scoring wood grain.

At the bottom, a basement stretched under a house that, outside, held no room for it.

Low ceiling, a grid of thick posts carved top to bottom.

Every inch of structure carried scratched lists: more names, more dates, more memory.

It looked like a tomb, like a record, like someone had taken the idea of accounting and turned it back against the accountant.

At the far edge, a small figure stood facing the wall.

Bare feet.

Torn shirt.

Silence in the shape of a child.

The boy did not run.

He did not flinch.

He turned only when Samuel spoke.

“Got you now,” Samuel said, stepping toward him.

The boy’s eyes caught lantern light and returned it like animal eyes flash in a midnight field.

Those pale eyes looked at each man in turn.

Not with fear.

Not with anger.

With something else—something that made Thomas take a step back before he could stop himself.

It felt like the boy was not looking at them but through them—something behind their faces was being counted.

“What’s your name?” Thomas asked, forcing steel into his voice.

The boy did not speak.

He never did.

He looked straight into Thomas, and something opened like a door inside Thomas’s head—a door he didn’t know existed.

Images flooded: faces he had hunted, hands he had tied, people he had dragged.

Mary, eight months pregnant.

He had caught her in 1857.

She had run not away but toward—toward a baby being sold.

He had brought her back and watched her child carried to wagon and ledger.

He had rationalized the scene as commerce.

Marcus, who ran after his wife, had been beaten by an overseer until he stopped moving.

Thomas had returned him to a rope under a tree and doubled his fee.

Sarah and two children in a barn north of town; he had shushed their crying with threats.

They all looked at him now through the boy’s pale lens, not pleading, not begging, just looking.

Thomas dropped his lantern.

Glass shattered and oil spread.

His mouth opened and nothing came.

His name slipped.

He did not remember who he was.

He fell to his knees, gasping like a man whose head had been held underwater too long.

Caleb snapped, “What is wrong with you?” Fear edged the harshness.

Thomas could not answer.

Speech had stripped away.

He made a sound like an animal that has lost language.

The air shifted—a deeper cold, winter pulled through the seams.

Samuel watched his breath—white in the dim.

The house felt awake now, not patient.

It felt pleased—a satisfaction that carried weight.

“We need to leave,” Robert said.

It was the first thing he had said inside.

“We came for the boy,” Samuel replied.

Even as he spoke, his legs felt heavy—as if wading a flooded field, as if hands held his thighs and kept him near the ground.

The boy tilted his head, and whispers rose in the room.

Names, dates, prayers in languages no one present could name.

Screams and pleadings.

All of it at once.

Samuel recognized voices he had ignored, pleas he had called weakness, beggings he had laughed at to harden his own heart.

They were here, lined into boards, present in air.

Elijah began to cry—not from fear but from weight.

Three hunts worth of chains and a handful of pleas collapsed on his chest.

He had believed the phrase—just the way things are.

The phrase dissolved in this place.

He sank and sobbed like a child.

“This is not natural,” Nathaniel whispered, knuckles white around the Bible.

His voice went high.

“This is the devil’s house.”

The boy finally moved—walking past them, slow, steady, toward the stairs.

Bare feet made no sound on dirt.

He passed within arm’s reach of Samuel, and Samuel could not move, as if agency had been removed from his body.

Caleb grabbed and caught air.

Jacob lunged and held nothing.

The boy climbed steps at human pace and stopped halfway up, turned, looked down at them, and something inside the men turned on itself.

Samuel saw Thomas as a thief who had stolen bounty credit three years prior—a memory he had buried at the time, now fresh as wound.

Thomas saw Samuel as a liar whose bad call had gotten Thomas’s brother killed during a hunt.

His brother’s death had been dismissed as an occupational hazard by the man who had led them.

Anger bloomed as if the conversation had happened minutes ago.

The Moss brothers felt every slight they had swallowed.

Every joke.

Every underpayment.

Every disrespect.

Nathaniel’s hand found the knife at his belt, eyes jumping between faces, convinced in an instant that someone planned to kill him and take his share.

The suspicion spread and seeded and sprouted.

Within seconds, each man believed the others had been enemies all along.

The boy climbed.

Beneath him the shouting started—accusations, pushes, backwards history coming forward like truth on a deadline.

Nathaniel fired first.

He would later say his finger slipped, that the gun went off.

The bullet took Jacob’s shoulder.

Jacob tackled Nathaniel, and they hit the dirt hard, rolling, elbows and fists.

Caleb grabbed his brother.

Samuel raised his rifle and fired into the ceiling—sound detonated in the low room.

For a moment, everything stilled.

“We need out,” Samuel shouted.

Saying it reset nothing.

The suspicion didn’t leave.

Robert stood apart, eyes seeming not to see anything in front of them.

Elijah bolted for the stairs.

He climbed—one, two, three steps—and the steps kept coming, lengthening like dreams do when you run and the hallway keeps stretching.

He collapsed halfway, crawled back down, throat raw with panic.

Robert moved to the wall while chaos reassembled.

A paper stuck in a seam drew his eye.

He slid it free—yellowed, brittle, careful hand used to letters.

He opened it and held it to a lantern.

My name is Elias Carter.

I was born in Virginia in 1821.

I was taught to read and write by the master’s daughter before they sold me south at fifteen.

I was brought in chains to Louisiana and owned by five men.

I learned carpentry.

I learned stone.

I learned how to build what stands.

In 1850 Edmund Tarrow bought my labor to build him a storage house in the woods—hidden, away from main buildings.

He showed me this clearing.

He told me to build something that would last a hundred years.

I did not build what he asked.

I built something else.

I built this house with purpose and memory.

Every nail drove a name.

Every board held a face.

Every beam lifted a prayer.

This is not shelter.

This is not storage.

This is a monument.

This is a trap.

This is revenge.

I carved every person I knew who died running, fighting, hunted and killed.

I put their names in these walls.

I put their memory in this wood.

I made this place remember.

I made it wait.

Edmund killed me when he saw the house.

He beat me with a shovel and buried me.

But the house was complete.

The house was awake.

It knows what it is for.

One day the hunters will come inside—men like those who caught me, men who made my friends disappear, men who call people property.

They will think they are chasing.

They will think they are in control.

The house will teach them different.

It will show every face they forgot, every name they never learned, every person they hurt.

The house takes names; it gives them back when it’s done—when it’s finished teaching, when everyone understands.

Some will die here.

Some will leave.

None will be the same.

None will forget again.

This is my work.

This is my legacy.

This house will stand longer than any plantation.

We will remember longer than any master.

We will wait as long as it takes—for justice, balance, truth.

My name is Elias Carter.

I built this in 1850.

I am still here.

E.

Robert lowered the paper.

The fight had paused.

All listened.

Thomas crawled nearer, eyes unfocused.

“It’s a trap,” Robert said quietly.

“Built for us.

We were meant to come.”

“That’s insane,” Samuel said, but his voice stripped confidence and carried tremble.

“Is it?” Robert asked, and gestured at walls dense with letters.

“How many of these did we carry back? How many did we let vanish into the ledger? How many did we forget?”

No one answered.

The boy was gone—no movement witnessed, no breath felt.

He had either always been part of the house or never had been there at all.

A lure.

Bait.

A hand that lifted the latch so the trap could close.

“We leave,” Robert said.

He folded the letter and slipped it into his pocket.

“Now.”

Samuel nodded.

The group gathered lanterns, lifted men.

Jacob stood, arm pressed, face gray.

Nathaniel clutched his Bible.

Elijah wiped his face.

Thomas moved slowly in the way people move when interior structures break.

They climbed.

The steps behaved like built things again.

The main room compressed into normal size.

The door opened.

Trees and afternoon light showed like promise.

Samuel reached toward the frame.

The house screamed.

Not human sound—wood and metal, nail and beam.

A thousand voices overlapped, each a name, each a story, each a demand.

Men fell to knees and clutched ears.

Sound burrowed into bone.

And then shadows lined the walls—figures human and still, a census made visible.

Men, women, children.

No expressions.

No gestures.

Only looking.

Samuel recognized faces he had refused to know.

Thomas saw Mary in a corner, hands cupped to belly; the Moss brothers saw a man they had beaten while laughing; Nathaniel saw a woman he returned to a cruel master; Elijah saw an old man he tied to a tree.

The shadows did not move.

They did not speak.

They did not threaten.

The scream stopped when Robert crossed the threshold and ran.

Outside, quiet fell like mercy.

He kept running, not counting steps, not hoping others would follow.

Inside, the six men carried hard recognition.

Samuel looked at the boy in the center of the shadows—pale eyes reflecting light like a lake at twilight.

The boy raised a hand and pointed at Samuel, then lowered it.

Samuel felt something collapse—walls he had built around his conscience, around his choices.

He saw himself clearly: not as a function of a system, not as a cog without agency, but as a man who had chosen to be cruel because cruelty paid well.

He screamed not from pain but from knowledge.

Each man broke in his own fashion: Jacob clawed his face as if vision could be erased; Caleb vomited; Nathaniel curled around his Bible, words a mix of prayer and panic; Thomas sat, tears still and constant; Elijah cried differently now, the kind of crying that says I know what I did.

The boy turned away, opened a back door none of them had seen, stepped through, and the door vanished.

The shadows faded.

The sound went out like a candle.

Silence returned.

They dragged themselves outside.

Sun stuck knives into their eyes.

They did not look at one another.

The house stood behind them—unaltered, patient.

“We burn it,” Caleb said, voice torn.

No one moved.

“You can’t burn memory,” Samuel said.

“It will stay.”

They walked to Hollow Pines without talk.

Two hours over dirt roads is long when men hold what they saw.

Edmund Tarrow stood at the main path waiting, voice high with entitlement.

“Where’s the boy?”

Silence stretched.

Samuel looked up with empty eyes.

“There is no boy,” he said.

“There’s only ghosts.

Only memory.

Only the things we pretended weren’t real.”

Tarrow squinted as if confusion could cancel reality.

“What in hell does that mean?”

“I’m done,” Samuel said.

“With all of it.

No more hunting.

No more dragging.

No more pretending.”

He turned and walked away.

Tarrow shouted.

Samuel did not stop.

The others dispersed like men leaving a funeral at different speeds.

The Moss brothers mounted quietly and rode.

Nathaniel walked toward the road with his Bible pressed to chest.

Thomas stared into nothing and then stepped into the woods—not toward the house, just away.

Elijah sat on the ground and cried until the sun went down.

Only Robert had run early.

Only Robert had taken the letter.

He reached New Orleans after two days, rented a small room in the Quarter, locked the door, and wrote names.

He wrote every name he could recall—faces, places, dates—covering one wall, then the next, then the ceiling.

He could not stop.

His fingertips bled.

When the landlord knocked and asked if he was well, he did not answer.

She let herself in days later and found him on the floor, still writing, surrounded by walls full of names.

She backed out and locked the door.

Three months later, Thomas Harlow hung himself in a Baton Rouge boarding house.

He used his belt and a low beam and died slowly.

He had mumbled names for weeks and filled a notebook with entries he crossed and recrossed.

The last page: “I’m sorry” written until ink blurred and sentences were a smear of apology.

Samuel Vickers walked into the Atchafalaya swamp and did not walk out.

Weeks later, searchers found him and did not recognize him at first; he had clawed his face until he had no eyes left, as if he could not bear the sight inside his head.

Caleb and Jacob Moss died in a fight said to be about cards.

Witnesses wondered because before knives flew, both men had been looking at a wall and speaking names into the room—asking forgiveness with a panic that sounded like confession.

Nathaniel Cross became a preacher.

He traveled towns with sermons about sin that made men weep, and his voice shook with a gravity truth gives.

He never smiled.

He died choking on a piece of bread in 1865, and the doctor said there was nothing in his throat—only a body that had forgotten how to accept sustenance, as if guilt had closed that passage.

Elijah lived nine more years.

He did not hunt again.

He clerked in a store.

He kept to himself.

He lived like a man who had seen a portrait of himself and did not like it.

He died slowly, wasting away as if his body had decided on its own to end.

Robert wrote names until he had no space left.

After he died, the landlord swore new names appeared on those walls—handwriting not her own, letters bleeding through fresh paint, script showing under wallpaper.

She locked the door and slid furniture against it.

On still nights, she heard scratching from the room.

Writing.

Always writing.

Edmund Tarrow sent twenty men with torches and oil to burn the forest house.

Flames died when they touched the wood.

Oil pooled uselessly.

Fire did not catch.

The men tried again.

Fire refused again.

Tarrow ordered the grove off-limits.

Runaways continued to disappear sometimes, and sometimes they returned with empty eyes and a lost few hours in their memory.

People whispered they had been in the house.

The house remembered; the house protected; the house punished.

Hollow Pines fell after the war.

Tarrow died angry and broke.

Land changed hands until a national forest absorbed it.

Old maps mark that region as unstable ground, not suitable for development.

Locals call the warning something else.

Hikers have reported seeing the structure where no structure should be—dark boards, slitted windows, tilting roof.

Some enter.

Most come out changed.

Some do not.

A sheriff’s deputy in 1923 went looking for a missing person.

He found the house, walked in, and walked out three hours later unable to speak.

He never spoke again.

A historian in 1957 tried to photograph it.

Every image came back black.

She tried a film camera.

Sound recorded names whispered at the edge of hearing.

She broke her equipment and left.

Four students entered in 1984.

Three returned.

The fourth was found two days later in the basement, humming a song nobody knew.

He hummed it until he died in an institution.

Nurses said they heard names in the melody.

A surveying team in 2009 stepped inside with radios and GPS.

Devices failed.

Ten minutes in, they walked out and quit their jobs.

One moved to Alaska.

One took vows.

One founded a research group dedicated to slavery and justice.

Asked why, he said, “I saw what I’d been blind to.”

The house still stands.

Elias Carter built it to last—not for shelter, but for accounting that does not depend on money.

It holds names.

It teaches those who have forgotten what forgetting does.

It reminds those who look away what looking away keeps alive.

Some places do not forget.

Some places will not let you.

Some places hold the debt until it is paid, until truth is spoken to the person who does not want it, until memory outweighs denial.

This house is one of those places.

It sits in the woods where a nation hid its worst stories under leaves and centuries.

It waits.

It teaches.

It carries names that were never given the dignity of being written and writes them where even paint cannot cover them.

It forces the accounting—face by face, name by name—until the men who called themselves hunters understand who was hunting whom, and why memory is the only fire some structures burn with.

News

The most BEAUTIFUL woman in the slave quarters was forced to obey — that night, she SHOCKED EVERYONE

South Carolina, 1856. Harrowfield Plantation sat like a crowned wound on the land—3,000 acres of cotton and rice, a grand…

(1848, Virginia) The Stud Slave Chosen by the Master—But Desired by the Mistress

Here’s a structured account of an Augusta County case that exposes how slavery’s private arithmetic—catalogs, ledgers, “breeding programs”—turned human lives…

The Most Abused Slave Girl in Virginia: She Escaped and Cut Her Plantation Master Into 66 Pieces

On nights when the swamp held its breath and the dogs stopped barking, a whisper moved through Tidewater Virginia like…

Three Widows Bought One 18-Year-Old Slave Together… What They Made Him Do Killed Two of Them

Charleston in the summer of 1857 wore its wealth like armor—plaster-white mansions, Spanish moss in slow-motion, and a market where…

The rich farmer mocked the enslaved woman, but he trembled when he saw her brother, who was 2.10m

On the night of October 23, 1856, Halifax County, Virginia, learned what happens when a system built on fear forgets…

The master’s wife is shocked by the size of the new giant slave – no one imagines he is a hunter.

Katherine Marlo stood on the veranda of Oakridge Plantation fanning herself against the crushing August heat when she saw the…

End of content

No more pages to load