I.The Discovery: A Sepia Mystery in South Philadelphia

The afternoon light filtered through the dusty windows of Riverside Antiques, casting long shadows across rows of forgotten furniture.

Thomas Reed, a veteran antiques dealer, was sorting through the latest estate sale haul from a demolished South Philadelphia rowhouse—a jumble of chipped dishes, worn quilts, and boxes of yellowed newspapers.

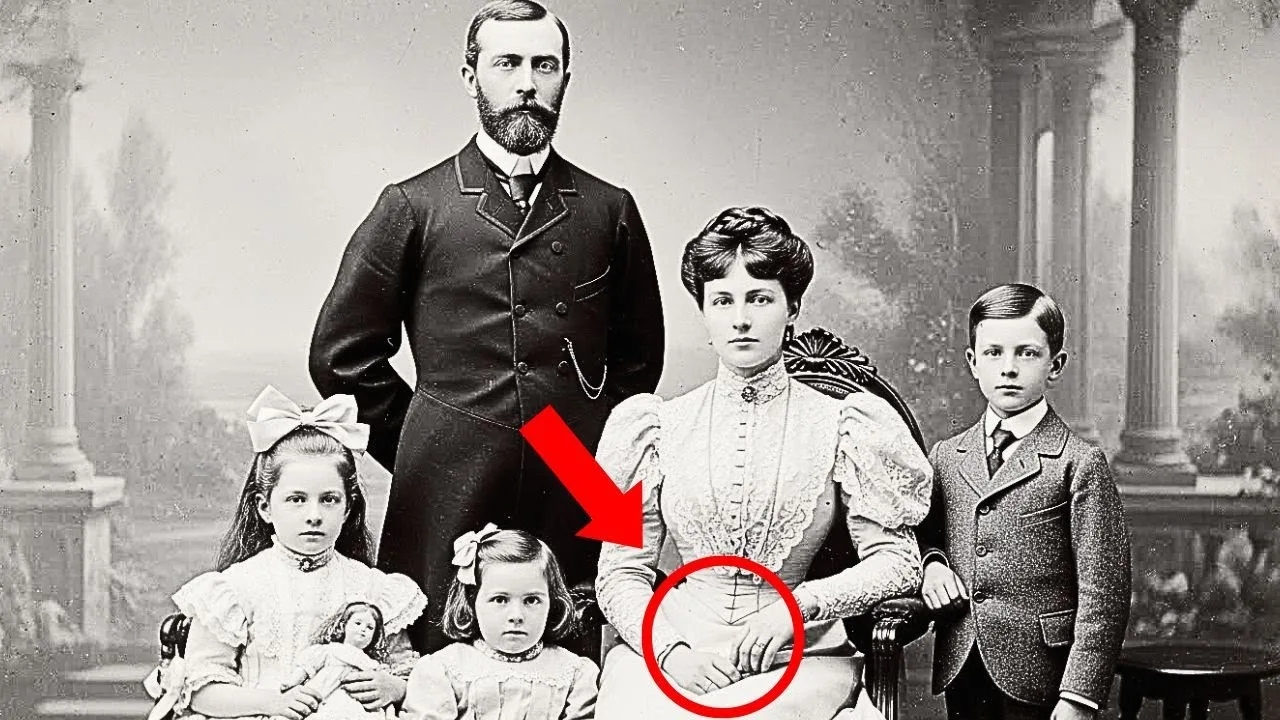

But one item stood out: a large wooden frame, its glass clouded with age, containing a formal family portrait in faded sepia tones.

The photograph was classic Victorian: a stern father standing behind a seated mother, three children arranged around them, all dressed in their finest.

Thomas carried the frame to his workbench, letting the natural light reveal more detail.

The father wore a dark suit with a high collar.

The children stared with uncomfortable stillness.

But it was the mother who drew his attention—her face beautiful but exhausted, her right hand gripping the arm of the chair.

Years of experience told Thomas something was off.

He retrieved his jeweler’s loop and examined the studio’s embossed mark: Whitmore and Sons Photography, Philadelphia, 1890.

Then he zoomed in on the mother’s hand.

Even through the faded sepia, the skin texture was rough—marked not by soft wrinkles, but by something harsher.

Thomas’s pulse quickened.

He carefully removed the backing and scanned the photograph at high resolution.

When he enlarged the mother’s hand, his breath caught.

The hand was covered in scars—deep burns, healed badly, leaving the skin textured and discolored.

The fingers were curved, unable to fully extend.

Along the back of the hand were puncture scars, small round marks in an almost geometric pattern.

In all his years, Thomas had never seen anything like it.

The portrait was meant to present the family at their best, yet the mother’s hand told a story of pain that contradicted everything.

II.

The First Clues: Industrial Scars and Social Class

The next morning, Thomas was at the Philadelphia City Archives, searching for clues.

He found Whitmore and Sons listed in 1890 business directories, a successful studio until a fire destroyed their records in 1904.

Frustrated, Thomas showed the high-resolution printout to archivist Patricia Morrison, who lingered on the mother’s hand.

She recognized the scars.

“Burns and puncture marks—these look like industrial accident injuries from the era.

Women in textile mills and garment factories worked dangerous machinery.

Steam presses caused burns; sewing machines caused puncture wounds.” But Patricia was puzzled.

“Women with injuries this severe rarely sat for formal portraits.

This looks like an upper middle class family.

If she was a factory worker, that dress would have been significant—maybe the only fine dress she ever owned.”

Patricia suggested Thomas speak with Dr.

Helen Vasquez at Temple University, an expert on women’s labor history in Philadelphia.

Thomas left the archives with more questions than answers.

Had the woman with the scarred hands been proud or ashamed when she sat for that portrait?

III.

The Historian’s Verdict: A Worker in Silk and Scars

Dr.

Vasquez’s office was filled with books and photographs of historical factory scenes.

She examined Thomas’s printout closely, her face pale.

She showed Thomas images of garment workers—women with scarred hands, exhausted faces, simple clothing.

“Philadelphia had dozens of garment factories south of Market Street.

Conditions were brutal.

Women worked twelve-hour days, six days a week, for wages that barely covered rent and food.

Steam presses caused severe burns; sewing machines sent metal shards into hands.”

But the portrait was different.

“This woman has the injuries of a factory worker, but she’s dressed like someone from a different class.

That dress would have cost months of a worker’s salary, and the formal portrait setting was something only wealthier families did.”

Dr.

Vasquez wondered if the woman had married into a better situation—or if something else was happening.

She explained the rise of the labor movement in the 1890s.

“Workers were organizing for better conditions.

It was dangerous—organizers were fired, blacklisted, even attacked.

Some persisted.”

She showed Thomas newspaper clippings from 1889 and 1890—major strikes at garment factories, mostly crushed, but a few women emerged as leaders.

“If you can identify this woman, you might have found someone whose story has been completely forgotten.”

IV.

The Search for a Name: Records of Resistance

At the Pennsylvania Historical Society, Thomas pored over industrial records related to garment manufacturing.

He found ledgers full of names, wages, and hours—steam press operators earning $4.50 a week, seamstresses injured on the job, wages docked for missed work.

After hours of research, archivist Robert brought him a folder from the Hartley Garment Company—a file about a strike in 1890.

Inside were memos, lists of suspected organizers, and a newspaper clipping: “Lady garment workers demand better treatment, walk-off jobs.” The article described forty women striking for shorter hours and safer conditions.

The leader was Mrs.

Elizabeth Brennan, age 29, steam press operator for nearly eight years, fired and removed by police.

Thomas found Elizabeth Brennan listed as “ring leader, immediate termination recommended, blacklisted.” He had a name.

Further research revealed Elizabeth married to James Brennan, living in South Philadelphia with three children.

Census records and factory memos showed James had resigned as foreman days after Elizabeth was fired—likely in solidarity.

Both were suddenly unemployed and blacklisted.

Yet somehow, they managed to scrape together enough money for a formal portrait.

V.

Family History Unearthed: The Descendants Remember

Thomas traced Elizabeth’s descendants, finding her grandson William’s daughter, Patricia Hughes, still living near Philadelphia.

When Thomas called, Patricia was stunned.

“You’re the first person outside my family who’s ever asked about Elizabeth.

Come to my house—I have things to show you.”

Patricia welcomed Thomas with warmth and curiosity.

She’d heard about the portrait her whole life, but never seen it.

Her grandfather said it was important, that it meant something.

As Thomas explained his research, Patricia nodded, then brought out a worn leather box filled with letters, documents, and photographs.

Inside was Elizabeth’s strike notebook—lists of names, notes about working conditions, demands for safer equipment, fair compensation, and no child labor.

“These demands were decades ahead of their time,” Thomas said.

“Most protections didn’t become law until the 1930s.”

Elizabeth’s courage became clear.

She risked everything to help other women.

James quit his job to support her.

They survived by borrowing money, taking odd jobs, and eventually opening Brennan Tailoring and Alterations—a small shop where Elizabeth worked for herself and never stopped advocating for workers.

VI.

The Portrait’s Power: Why She Showed Her Scars

Thomas asked why, after losing everything, Elizabeth insisted on a formal portrait.

Patricia’s eyes were bright.

“Grandfather said Elizabeth wanted a record of who they were at that moment—a woman with scarred hands, a man who’d chosen love over security, and their children.

She wanted proof they existed, that they mattered, that they had fought.”

Elizabeth knew history forgets ordinary people, especially women and workers.

She wanted evidence.

She wore her finest dress, held her head high, and let her scarred hands show—so people would see the cost of factory work and fighting back.

She wanted future generations to know.

Patricia shared more documents: letters about organizing, a newspaper clipping from 1916 describing Elizabeth speaking at a workers rally.

“Twenty-six years ago, I stood outside a factory with forty brave women and demanded our basic rights.

We were defeated, but we planted a seed.

Now, I see that seed has grown into something unstoppable.”

Elizabeth lived to see labor unions gain real power, laws passed to protect workers, and the vindication of her struggle.

VII.

The Legacy: A Family Changed by Courage

Elizabeth’s children carried her values forward.

Margaret became a teacher and union activist; William became a labor lawyer; Dorothy became a social worker.

All spent their lives fighting for fairness and justice.

Elizabeth’s portrait was her most prized possession—a testament to choosing to stand for something larger than herself.

Thomas and Patricia donated the portrait and documents to the Philadelphia Workers History Museum.

The exhibition, centered on Elizabeth’s portrait, drew thousands in its first month.

Visitors studied her scarred hands, read her letters, and learned about the brutal realities of factory work and the courage of those who resisted.

A young girl asked her mother why Elizabeth showed her hurt hands.

“She wasn’t ashamed,” her mother replied.

“She was brave.”

For Thomas and Patricia, the exhibition fulfilled Elizabeth’s wish: that ordinary workers, especially women, wouldn’t be forgotten by history.

VIII.

The Photograph’s Message: Dignity and Defiance

The 1890 portrait, once a forgotten relic, became a powerful symbol—a window into a lost chapter of American history, a testament to courage and sacrifice.

Elizabeth’s scarred hands, once a source of shame, were now a symbol of dignity, resistance, and hope.

Her story, nearly lost to time, will now inspire generations to come.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load