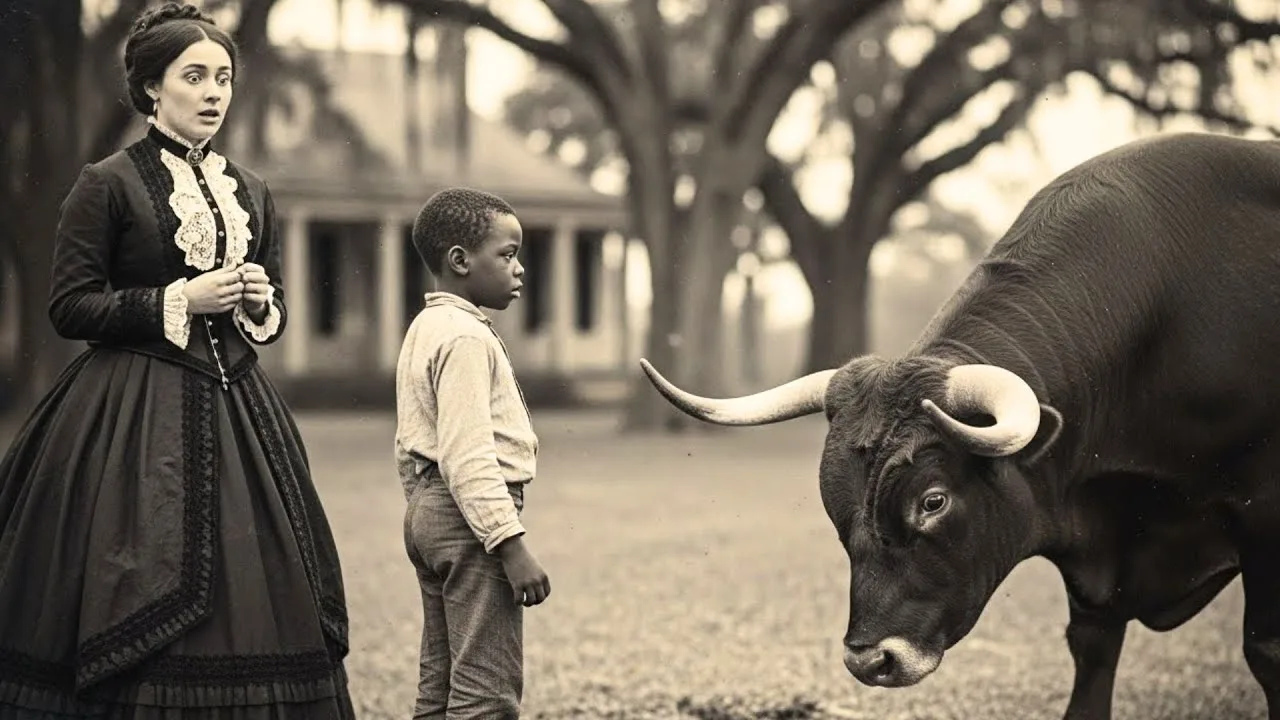

(1877, Silas Bennett) The Enslaved Boy Who Saved the Plantation Mistress from a Wild Bull

Welcome to the channel Stories of Slavery.

Today’s story is about Silus Bennett, an enslaved boy in 1877 who saved the plantation mistress from a wild bull.

And what happened afterward shocked everyone who witnessed it.

This is a tense and emotional story.

So, take a moment, breathe, and listen carefully.

Before we begin, make sure to subscribe to the channel and write in the comments which city and country you’re listening from.

Your participation helps keep these stories remembered instead of buried.

Let’s begin.

The blood was still warm on his back when they dragged him to the auction block for the second time in his life.

Silas Bennett was 16 years old, and he had just learned the crulest lesson of the American South, that saving a white woman’s life could be a worse crime than letting her die.

This is the story of a boy who spoke to animals better than he spoke to men.

Who committed the unforgivable sin of heroism in 1877 Georgia and who transformed from the gentlest soul on the Callahan plantation into something the night itself learned to fear.

Georgia 1877, the year the North gave up on the South.

Federal troops had withdrawn three months earlier, ending what historians call reconstruction and what white southerners called occupation.

In Washington, politicians shook hands over a compromise that abandoned 4 million freed people to the mercy of their former masters.

Rutherford Hayes took the presidency and the South took back its old ways.

For people like Silas Bennett, freedom was a word that existed only on paper yellowing in some distant courthouse.

His father, Moses Bennett, had signed what the white landowners called a sharecropping contract in 1868.

Moses couldn’t read the document he marked with an X, but the white man who held the pen assured him it was fair.

The contract bound the Bennett family to work Henry Callahan’s land until they paid off their portion of seed, tools, and the shack they lived in.

The debt never got smaller.

It only grew.

Every harvest season, Moses would stand in the plantation office while Callahan’s overseer, a narrow-faced man named Garrett, ran his finger down a ledger and announced the family owed more than they’d earned.

The price of seed had gone up.

The quality of cotton had gone down.

There were fees for the mule, fees for the plow, fees for living on land that used to be worked by people who weren’t paid at all.

Silas had been born into slavery in 1861.

Too young to remember the war, but old enough to understand that the chains on his family now were made of paper instead of iron.

They cut just as deep.

The Callahan plantation sat in the red clay hills of central Georgia, 3,000 acres of cotton fields, timber stands, and pasture land.

The main house was a white column structure that had survived Sherman’s march by pure geography, standing proud on a rise that overlooked the worker quarters below.

73 families lived on Callahan land in 1877.

All of them black.

All of them bound by contracts they couldn’t read and debts they couldn’t pay.

But Silas Bennett didn’t spend his days in the cotton fields.

He had a gift that even Henry Callahan couldn’t ignore.

The boy could speak to animals.

Not literally, of course.

Silas didn’t hear voices or receive messages from the spirit world, despite what some of the older workers whispered when they saw him calm a wildeyed stallion with nothing but his hands and his voice.

What Silas possessed was something rarer than magic, something that couldn’t be taught or bought or bred into a person.

It was pure empathy, an ability to read an animals fear in the tension of its muscles, its rage in the flare of its nostrils, its pain in the way it held its weight.

He moved among horses, cattle, and dogs like he was one of them, speaking their language of breath and posture and careful stillness.

When Silas was 11 years old, Garrett had brought a new stallion to the plantation, a magnificent black Tennessee walker that Callahan had purchased at auction in Atlanta for $200.

The horse was beautiful and completely unmanageable.

It had kicked two experienced handlers and bitten a third.

Garrett was preparing to have the animal gilded and broken with the traditional methods employed throughout the south, rope, whip, and the systematic crushing of its spirit until nothing remained but obedience born of terror.

Silas had been mucking stalls when he heard the commotion in the paddock.

He climbed the fence and watched the stallion rear and scream, eyes rolling white with terror.

Three men with ropes were trying to corner it against the back wall.

The horse’s fear was so thick, Silas could almost taste it, metallic and sharp like blood in his mouth.

He’d climbed into the paddock before he’d even thought about what he was doing, moving on pure instinct.

The men shouted at him to get out, their voices harsh with anger and alarm, but Silas ignored them completely.

He walked toward the stallion with empty hands and downcast eyes, making himself small, making himself safe, making himself into something that posed no threat.

He didn’t approach directly, but at an angle, giving the horse space to move, space to choose, space to understand that flight was still an option.

When he got within 10 ft, he started humming.

A low, tuneless sound that came from deep in his chest, a vibration more than a melody.

The stallion’s ears swiveled toward him like compass needles finding north.

Silas stopped moving and kept humming, letting the sound fill the space between them.

He didn’t look at the horse’s eyes, knowing with the certainty of long experience that direct eye contact meant challenge in the animal world, meant threat, meant the possibility of violence.

Instead, he watched its feet, its breathing, the gradual softening of the muscles in its neck as the terror began to drain away degree by degree.

5 minutes passed in absolute silence, except for that low humming.

Then 10.

The other men stood frozen against the fence, barely breathing, afraid to move and break whatever spell the boy was casting.

The stallion took a step towards Silas, then another, its nostrils flaring as it caught his scent, and found nothing there to fear.

15 minutes later, Silas had his hand on the horse’s neck and was breathing in rhythm with the animal, their lungs rising and falling together like dancers moving to music only they could hear.

The men with ropes stood watching, their mouths hanging open in disbelief at what they just witnessed.

Henry Callahan himself had been watching from his position at the fence, having come down from the main house to check on the progress with his expensive new acquisition.

He was a tall man, 53 years old in 1877, with iron gray hair and the bearing of someone who’d never questioned his right to command.

He’d owned enslaved people before the war and owned their labor still, just under a different name and a different system of accounting.

He was not given to displays of emotion or surprise, but what he’d just seen had genuinely impressed him.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” he said, his voice carrying clearly in the sudden quiet of the paddock.

“Boys got the touch, seen men work with horses for 40 years and never develop what that child just did natural.” From that day forward, Silus Bennett became the Callahan plantation’s primary animal handler.

pulled from the cotton fields where his parents and sisters still labored, and given sole responsibility for the horses, cattle, and the plantation’s pack of hunting dogs.

It was better work than picking cotton under the brutal August sun, though Silas was careful never to appear too happy about his position, never to show too much pride or satisfaction.

Showing pleasure in anything was dangerous for a black boy in Georgia.

Happiness could be taken away as quickly as it was given, and often was, just to remind you of your place in the order of things.

Silas lived for the hours he spent in the stables and pastures, the early mornings and late evenings, when he could work with the animals, in relative peace.

Animals made sense to him in a way that people never had and probably never would.

A horse didn’t care about the color of your skin or the circumstances of your birth.

A dog didn’t change its feelings based on who was watching or what social rules might be violated by simple affection.

When a cow was frightened, you could see exactly why and address the cause directly, honestly, without having to navigate the complex and often deadly social codes that governed every interaction between black and white in the postwar South.

Animals were honest in their needs and clear in their communications.

They might be dangerous, certainly, their power and instincts making them potentially deadly, but they were never cruel.

They never hurt for the sake of hurting.

They never punished you for things you didn’t do or couldn’t control.

The same couldn’t be said for men, particularly white men in Georgia in 1877.

Garrett, the overseer, watched Silas with the permanent suspicion that white men of his type carried like a weapon, always loaded, always ready to fire.

He was 34 years old, rail thin from a constitution that couldn’t seem to hold weight no matter how much he ate, with tobacco stained teeth and a voice like rocks scraping together in a dry riverbed.

Before the war, he’d been an overseer of enslaved people on a plantation in South Carolina.

After the war, he drifted west to Georgia and found work overseeing sharecroers.

The only difference to him was paperwork and the fact that he couldn’t legally kill the workers anymore.

Though the convict leasing system that had sprung up across the south provided workarounds for men who understood how the new system really worked.

Garrett didn’t like that Silus had a special position on the plantation.

He didn’t like that Henry Callahan sometimes spoke directly to the boy instead of going through proper channels and the established hierarchy.

Most of all, he didn’t like that Silas was good at something Garrett himself could never do, that the boy possessed a skill that couldn’t be learned through violence or intimidation or the assertion of white superiority.

Boys got ideas above his station.

Garrett told the other white men who worked the plantation.

The overseers and foremen who gathered in the equipment shed to drink whiskey and complain about the workers.

Thinks he’s special because he can sweet talk a horse.

Needs to remember his place.

Remember what he is.

But as long as Silas kept the animals healthy and productive, Callahan protected him from Garrett’s worst impulses and his desire to cut the boy down to size.

The plantation owner was above all things a practical man, more interested in profit than ideology.

He’d paid good money for his breeding stock, hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars for individual animals, and the Bennett boy kept them in prime condition.

The horses never went lame under Silus’s care.

The cattle stayed fat and healthy.

The dogs were loyal and well-trained, perfect for hunting the deer and wild pigs that roamed the Georgia forests.

Silas understood with the clarity of someone whose life depended on it, that his value was measured entirely in dollars and productivity, in the health of animals that were worth more than he would ever be.

He was careful in everything he did, methodical and quiet and precise.

He did his work and kept his head down and made himself as invisible as possible.

He’d learned early that being noticed was dangerous unless you were being noticed for something that made your owner money.

The other person who noticed Silas, though for entirely different reasons, was Elellanena Callahan.

She was 26 years old in 1877, married to Henry Callahan for 8 years, and profoundly lonely in the way that only women of her class and time could be.

isolated by the very privileges that were supposed to make her happy.

Elellanena had been raised in Savannah society, the daughter of a cotton merchant who’d survived the war by selling to both sides and asking no questions about politics or loyalty.

She’d been educated at a finishing school run by French nuns, trained in piano and watercolors, and the elaborate social rituals that govern the lives of southern ladies.

Her days had been filled with calling cards and tea parties and the careful cultivation of marriageable grace.

Her marriage to Henry Callahan had been arranged by their fathers over brandy and cigars in a Savannah gentleman’s club.

The two men trading their children like shares in a profitable venture.

Henry was 43 at the time, 17 years her senior, a widowerower whose first wife had died giving birth to a stillborn son.

He needed a new wife to manage his household and produce an heir to inherit the plantation.

Elellanena’s father needed connections to George’s planter class to expand his business interests.

It was a practical arrangement that benefited everyone except possibly Elellanena herself.

They were married in Savannah’s Cathedral of St.

John the Baptist in the spring of 1869, and Elellanena moved to a plantation 30 mi from the nearest town, surrounded by people who had once been enslaved, and white men who spoke of nothing but cotton prices and politics and the glorious lost cause of the Confederacy.

She had no friends in this new place, no children despite 8 years of marriage and trying, and a husband who treated her with the same distant politeness he showed to dinner guests and business associates.

Henry was not cruel to her.

He simply had no particular interest in her beyond her function as the mistress of his household and the potential mother of his heirs.

When that function remained unfulfilled year after year, his indifference deepened into something close to disappointment, though he never spoke of it directly.

Eleanor spent her days supervising the house servants, arranging flowers in rooms no one visited, playing piano in an empty parlor where the music echoed off the walls, and looking out windows at a world she was forbidden to truly enter.

Southern ladies of her class didn’t work.

They didn’t have purpose beyond decoration and the hope of sons.

She was a beautiful object in a beautiful house, carefully maintained and profoundly useless, and she was dying of it in ways that had no name and no cure.

She’d first noticed Silas Bennett 3 years earlier in the summer of 1874, watching from the ver as the boy worked with a particularly difficult mare in the training paddock.

The mayor had been abused by her previous owner, a man who’d lost the plantation in a card game and sold off his stock before the new owner could claim it.

She would strike out with her hooves at anyone who approached, her eyes rolling white with remembered terror.

But the Bennett boy had spent hours, then days, then weeks, just sitting in the paddic with her, not moving, barely breathing, simply being present until the mayor got used to his existence.

Elellanena had watched the entire process unfold over the course of a month, fascinated despite herself.

She’d seen patience and gentleness in the way the boy moved, qualities that were rare in the harsh world of the plantation, where force and dominance were the primary currencies of interaction.

She’d seen him succeed where grown men with whips and ropes had failed completely.

She’d mentioned it to Henry once over dinner.

The two of them sitting at opposite ends of a table designed to seat 20, eating in near silence as they did most nights.

“That boy you have working with the horses is quite remarkable,” she’d said, her voice sounding too loud in the quiet dining room.

“Henry had looked up from his roast beef, his expression mildly curious.” “Which boy?” he’d asked.

“The young one.” Silas, I believe his name is,” Elellanena had replied.

“Oh, the Bennett boy.

Yes, he’s useful with the animals.

Got a natural knack for it.

Saves me money on veterinary bills and lost stock.” That had been the extent of the conversation.

Henry didn’t encourage his wife to take interest in the workers, black or white.

It wasn’t proper for a lady to concern herself with such things beyond the household servants she directly supervised.

But Elellanena continued to watch when Silas worked near the house, observing from her windows like a prisoner watching the free world beyond the bars.

She never spoke to him directly.

The social distance between a plantation mistress and a black worker boy was an unbridgegable canyon, carefully maintained by a thousand unspoken rules that governed every aspect of southern life.

She simply observed from her elevated position and felt a strange envy for the purpose and skill she saw in his work, for the clear meaning his days seemed to have.

At least the boy had something to care about, something that cared back in its way.

At least he had a reason to wake up in the morning beyond the empty performance of respectability.

Elellanena’s life was composed entirely of surfaces and appearances.

A carefully constructed facade behind which nothing of substance existed.

She was 26 years old and already felt like a ghost haunting her own existence.

The spring of 1877 brought unusual heat to Georgia, temperatures climbing higher and earlier than anyone could remember.

By midappril, the thermometer on the plantation’s main porch was already reaching into the high8s by midday, and the red clay earth cracked and dried like old leather.

Water became precious.

Tempers shortened.

The heat made everything harder, turned simple tasks into orals, and brought out the worst in both animals and men.

Henry Callahan had invested heavily in expanding his cattle operation over the winter, seeing opportunity where others saw only risk.

Cotton prices were unpredictable, subject to the whims of northern textile mills and international markets.

But beef was bringing good money from the growing cities of the south and the railroad connections that now ran through Georgia like veins carrying commerce.

He’d purchased a prize breeding bull from a Texas rancher in February.

an enormous longhorn that the seller claimed had sired 50 calves in three years and possessed the best bloodlines west of the Mississippi.

The price had been steep, $300, but Callahan believed in the investment.

Good breeding stock would pay for itself many times over.

The bull arrived by railc car in early March, and it took six men with ropes and poles to unload it from the stock car at the depot.

The animal was absolutely monstrous in size and temperament.

It stood nearly 6 feet at the shoulder and weighed close to 2,000 lb, with horns that spread 5 ft from tip to tip, their points as sharp as cavalry sabers.

Its hide was a modeled pattern of brown and white, and its eyes were the color of old amber filled with an intelligence that bordered on calculation, on conscious malevolence.

This was not a domesticated animal in any real sense.

This was barely contained wildness, power, and rage held in check by nothing but fence posts and the animals own momentary choice to cooperate.

Henry Callahan named it Leviathan after the biblical sea monster, and the name fit perfectly.

Silas had been assigned to manage the bull’s integration into the plantation’s breeding program, a responsibility that filled him with equal parts pride and terror.

It was dangerous work under the best circumstances.

Bulls were unpredictable at the best of times, driven by instincts that could turn them from calm to violent in a heartbeat.

And Leviathan had the added volatility of being in an unfamiliar place with unfamiliar animals and unfamiliar humans.

The first time Silas approached the bull’s pen, Leviathan charged the fence with enough force to crack one of the thick oak support posts.

The impact sounded like a gunshot echoing across the barnyard and Silas had jumped back instinctively, his heart hammering against his ribs like it was trying to escape his chest.

He stood at a safe distance and studied the animal for a long time, watching how it moved, how it held its massive head, how it reacted to the presence of the other cattle in adjacent pens.

This was not like working with horses.

Horses were prey animals governed by flight instinct and the desire for safety for the protection of the herd.

Bulls were different creatures entirely.

They had the confidence of animals that had few natural predators, the arrogance of power.

Leviathan didn’t fear humans the way horses did.

It tolerated them at best and challenged them at worst.

Seeing them as potential rivals for dominance rather than threats to flee from, Silas spent weeks just observing the bull, learning its patterns and rhythms.

He noticed that Leviathan was calmer in the early morning hours, more aggressive in the heat of the afternoon when the sun beat down and the flies swarmed.

The bull had already established a hierarchy with the other cattle, and it would posture and bellow to maintain its dominance, but it didn’t actually attack if the other animals showed proper deference and submission.

It was testing, always testing, looking for weakness or challenge.

Slowly, carefully, moving with the patience he’d learned from years of working with difficult animals, Silas began to enter the bull’s space.

He never approached directly, never made sudden movements, never did anything that could be interpreted as a challenge or threat.

He would enter the large paddock that held Leviathan and several cows moving along the fence line, giving the bull plenty of room to observe him and make its own choices.

He’d scatter feed in the troughs, and then retreat immediately.

approach and retreat.

Approach and retreat, always predictable, always slow, always giving the animal time to adjust to his presence.

By late April, after nearly 2 months of this patient work, Silas could work in the same paddock as Leviathan without incident.

The bull had learned that the boy was not a threat and not a rival, that he represented food and water and the opening of gates to better pasture.

They had reached an understanding, a working relationship based on routine and predictability.

But understanding was not the same as trust.

And Silas never forgot for a moment that wild animals could turn in a heartbeat.

That all his careful work could be undone by a single wrong move or an unexpected sound.

The morning of April 28th, 1877 started like any other morning on the Callahan plantation.

Silas woke before dawn in the one room cabin he shared with his parents and younger sister Maya.

The cabin was cramped and dark with a dirt floor and walls made from rough cut pine that had warped and shrunk over the years, leaving gaps that let in the cold in winter and the heat in summer.

His father was already gone to the cotton fields, leaving before first light as he did every day during the growing season.

His mother, Ruth, was stirring cornmeal mush over the small fire, preparing the only meal the family would eat until evening.

The cabin smelled of smoke and fatigue and the particular poverty that no amount of work could seem to lift.

“You be careful with that devil bull today,” Ruth said as Silas pulled on his work boots.

The leather cracked and stiff from age.

She said the same thing every morning.

And every morning, Silas gave the same response.

the ritual as much a part of their routine as the meal she was preparing.

“Yes, mama,” he replied.

“That animal ain’t natural,” Ruth continued, her voice low and worried.

“Got the devil’s own temper.

I seen the way it looks at people.

Ain’t right.

I’m careful, mama.

I know what I’m doing.” Ruth turned from the fire and looked at her son.

Really looked at him in the dim light of early morning.

At 16, he was already taller than she was.

With his father’s broad shoulders and her own dark eyes, he’d grown into someone she hardly recognized.

Sometimes, transformed from the child she’d nursed through fevers and hunger into a young man who moved through the dangerous world of the plantation with careful grace and quiet competence.

“I know you are, baby,” she said softly.

“But careful don’t always matter when you dealing with beasts and white folks.

Both of them can turn on you for no reason at all.

And there ain’t nothing you can do but pray and run.

Silas kissed his mother’s cheek, feeling the papery texture of her skin, aged beyond her 38 years by work and worry and the grinding stress of never having enough.

He headed out into the pre-dawn darkness, walking the familiar path from the quarters to the main complex of barns and stables.

His breath misted in the cool air, and somewhere in the distance he could hear roosters beginning to crow, announcing the coming day.

The world was quiet in that brief window between night and morning, and Silas loved this time above all others.

These were the hours when he had the animals to himself, when the white men were still sleeping off their whiskey, and the other workers were just beginning to stir.

He could work in peace, moving through his routines without supervision or comment or the constant awareness of being watched and judged.

Silas fed the horses first as he always did, measuring out oats and hay with careful precision, checking water troughs to make sure they were full and clean, running his hands over legs and backs and necks to check for heat or swelling that might indicate injury or illness.

Then he moved to the cattle pens, counting heads to make sure none had escaped or died during the night, looking for any signs of sickness or distress in the herd.

When he reached Leviathan’s paddock, he stopped and felt his stomach drop.

The bull was standing in the center of the enclosure, absolutely motionless, its massive head lowered almost to the ground.

Something was wrong.

Silas could see it in the animals posture in the way it was holding its weight.

He approached the fence carefully, moving slowly, and studied the bull from a safe distance.

Leviathan’s breathing was labored, its sides heaving with each breath.

Foam flecked its muzzle, hanging in white strings.

One of the rear legs was held at an odd angle, not bearing full weight, suggesting injury or pain.

Silus’s mind raced through possibilities, running down the mental checklist he’d developed over years of animal care.

injury from the fence, snake bite, poison from bad feed, or contaminated water.

He needed to get closer to assess the problem properly.

But Leviathan in pain would be even more dangerous than usual.

Injured animals were unpredictable, driven by survival instinct and fear rather than any kind of reason or learned behavior.

Pain made them wild again, stripped away the thin veneer of domestication.

Silas climbed the fence and dropped into the paddic, his boots hitting the dirt with a soft thud.

The bull’s head came up immediately and those amber eyes fixed on him with an intensity that made his skin prickle with instinctive alarm.

Leviathan took a lurching step forward, clearly favoring the injured leg and released a low bellow that sounded like thunder rolling across the distant hills.

Easy now, Silus said softly, keeping his voice calm and level despite the fear crawling up his spine.

Easy, boy.

I’m here to help you.

Just let me see what’s wrong.

He moved slowly to the side, trying to get an angle where he could see the injured leg properly.

As he moved, he kept talking.

That same low, cruning tone he used with frightened horses.

The words themselves meaningless, but the tone carrying everything.

The words didn’t matter.

They never did.

The tone was everything.

The emotion behind the sound.

Leviathan tracked him with its head.

Muscles bunching beneath that mottled hide, preparing for something.

Silas could see the problem now.

There was a long, jagged gash on the bull’s left rear leg just above the hawk joint.

It looked fresh, probably from catching the leg on a broken fence board during the night.

One of the hundreds of small maintenance issues that plagued any working plantation.

The wound was bleeding, but not severely, a slow seep rather than an arterial flow.

It needed to be cleaned and treated with one of the picuses Silus prepared from herbs and lamp oil, but it wasn’t life-threatening.

The problem was getting close enough to treat it without being killed in the process.

You got yourself hurt, didn’t you, boy? Silas continued his soft patter, taking another careful step forward.

We’re going to fix that.

Going to make it better.

But you got to let me help you.

You got to trust me.

He took another step forward, his hands extended and empty, showing the bull he carried no weapons, no ropes, nothing threatening.

Leviathan exploded into motion without warning.

The bull charged with a speed that seemed physically impossible for an animal that size, going from standing still to full attack in less than a second.

One moment it was simply standing there, and the next it was a 2,000lb missile of muscle and horn, heading straight for Silas with the clear intention of killing him.

Silas ran for his life, sprinting toward the fence with every ounce of speed his 16-year-old body could produce.

His boots slipped in the loose dirt of the paddock.

He could hear the thunder of hooves behind him, could feel the heat of the bull’s breath on his back, could hear the rasp of its breathing.

He hit the fence at full speed and vaulted it in one desperate motion, tumbling over the top rail and landing hard on the other side, rolling through the dirt and coming up, gasping for breath.

Leviathan hit the fence a half second later with enough force to splinter two of the thick oak rails.

The bull’s horns punched through the wood like it was paper, missing Silus’s previous position by mere inches.

The animal bellowed its rage and frustration, pouring the ground, tossing its massive head.

The injured leg seemed completely forgotten in the fury of the moment.

Silas lay in the dirt, his heart trying to hammer its way out of his chest, his breath coming in ragged gasps.

That had been close.

too close.

He’d nearly been killed, and only blind luck and youth and the split-second timing of his vault had saved him.

“Boy, what the hell’s going on here?” Garrett’s voice cut through the morning air like a knife.

The overseer was striding across the yard from the direction of his quarters, pulling his suspenders up over his undershirt, his face already twisted with anger, even before he knew what had happened.

Anger was Garrett’s default state.

the baseline from which all other emotions departed and to which they always returned.

Silas got to his feet quickly, brushing dirt from his clothes.

The bulls injured, sir, cut his leg on something in the night he’s agitated and dangerous.

Garrett looked at the damaged fence and the bellowing Leviathan beyond it, then turned his narrowed gaze back to Silas.

“You antagonize that animal?” he demanded.

“No, sir.

I was just trying to check the injury to see how bad it was.

Don’t look like checking to me, Garrett interrupted, spitting a stream of tobacco juice into the dirt near Silus’s feet.

Looks like you got him riled up and nearly got yourself killed.

Mr.

Callahan paid $300 for that bull.

He finds out you’ve been mistreating his stock.

They’ll be hell to pay.

I wasn’t mistreating him, sir.

I was trying to help.

Don’t sass me, boy.

Garrett’s hand moved to the coiled whip on his belt, a casual gesture that carried volumes of threat.

The whip was always there, always within reach, a constant reminder of the violence that underpinned every interaction.

You go on and get the other animals fed.

I’ll deal with the bull myself.

Get some real men to handle it proper.

Silas wanted desperately to explain that Leviathan was injured and frightened.

that approaching him now would be dangerous for anyone, regardless of their color or experience, that the bull needed time to calm down before anyone tried to treat the wound.

But he knew better than to argue with Garrett.

Arguing only made things worse, only gave the overseer an excuse to escalate, to assert his authority through violence.

Silas ducked his head in the posture of submission that had been beaten into him over 16 years and moved away quickly, heading toward the horse stables.

Behind him he heard Garrett calling for other men to help with the bull, his voice harsh and commanding.

The day grew hotter as the sun climbed higher in the sky, the temperature rising degree by degree until the air itself seemed to shimmer and warp.

By 10:00 in the morning, the thermometer on the plantation’s main porch was already reading 92°, and there wasn’t a breath of wind to provide relief.

The plantation moved at the slower pace that heat demanded, men seeking shade where they could find it.

Animals standing listless in their pens with their heads down.

Henry Callahan had business in town and had left early in his carriage, taking his driver and his account books to meet with the banker about loans for the coming season.

That left Garrett in charge of the plantation, a situation that made everyone nervous, black and white alike.

The overseer had a mean streak that Callahan’s presence usually kept in check.

But when the boss was away, Garrett’s true nature came out to play.

Elellanena Callahan was in the main house, trapped in the prison of her corset and petticoats and the three layers of clothing that propriety demanded, even in killing heat.

She’d spent the morning reviewing household accounts with Bessie, the head house servant, going over expenditures for candles and soap and flour in a ritual that served no real purpose beyond filling the empty hours.

The tedium of it, combined with the oppressive temperature, had given her a vicious headache that pounded behind her eyes like a hammer on an anvil.

She decided to take a walk through the gardens before lunch, hoping that movement and fresh air might ease the pain, though the air outside was hardly fresh, just hot and still and heavy.

The gardens on the Callahan plantation were Elellanena’s one creative outlet.

the single area where Henry allowed her full control and didn’t question her decisions or expenditures.

She’d spent years developing them, importing rose bushes from Charleston and Aelas from Savannah, creating intricate paths and carefully planned beds that provided color from early spring through late fall.

It was a small sanctuary of beauty in the harsh landscape of the plantation, a place where she could pretend for a few minutes that she was something more than an ornament in her husband’s house.

She walked the shaded paths between flowering beds, her parasol providing meager relief from the brutal sun.

She was thinking about nothing in particular, her mind mercifully empty of the usual shunan of worry and loneliness and regret when she heard the commotion from the direction of the cattle pens.

Men’s voices raised in alarm and panic, the sound of wood splintering and crashing, and beneath it all a roar that made the ground vibrate beneath her feet.

A sound of pure animal rage that triggered something primal in her hindb brain.

Elellanena’s headache disappeared instantly, replaced by a spike of pure adrenaline that made her heart race and her breath come short.

She knew that sound.

She’d heard Leviathan bellow before during feeding times when the bull was establishing dominance over the other cattle.

But this was different.

This was not a challenge or a warning.

This was fury.

She should have returned immediately to the house.

should have sent Bessie to find out what was happening while she waited in the safety and propriety of the parlor.

A lady had no business near the working areas of a plantation, and certainly no business near agitated livestock, but curiosity and boredom and 8 years of stifling constraints pushed her forward instead of back.

She walked toward the cattle pens, staying on the path that ran along the eastern fence line, partially hidden from direct view by a row of magnolia trees that provided blessed shade.

She reached a gap in the trees and looked through at the scene unfolding in the main yard.

What she saw was absolute chaos.

Leviathan was free in the main workyard, having apparently broken through the weakened section of fence that his earlier charge had damaged.

The bull was in full fury, its injured leg apparently not hindering its movement at all.

Four men with ropes were trying to corner it against the barn wall, but the animal was having none of it.

As Elellanena watched from her hidden position, Leviathan charged one of the men, a fieldand whose name she didn’t know.

The man barely managed to dive behind a water trough, his body hitting the dirt hard.

The bull’s horns caught the wooden trough and flipped it like it weighed nothing, sending a 100 gallons of water spraying across the yard in a glittering ark.

This was madness.

The men were going to get killed.

And then Elanor’s attention was drawn to a fifth figure separate from the men with ropes standing near the horse stable with something in his hands.

It was Silas Bennett, shirtless in the heat, holding a wooden bucket.

Elellanena watched as the boy took a step toward the rampaging bull, then stopped, his entire body tense with indecision.

He looked toward the men, toward the bull, clearly trying to decide something, calculating odds and possibilities.

Then he started walking forward, the bucket held in front of him, his posture deliberately non-threatening, his movements slow and predictable.

What was the boy doing? Elellanena felt her breath catch in her throat as she watched Silas move closer to the enraged bull.

Garrett saw him too, and his voice cracked across the yard like a whip.

Boy, you get back.

This ain’t your concern.

But Silas ignored him completely.

His attention focused entirely on Leviathan.

He kept walking forward with that strange confidence Elellanena had seen him use with difficult animals before, that quality of absolute calm that seemed to radiate from him like heat from a stove.

The bucket swung slightly in his hands, and Elellanena could see now that it was filled with feed, the grain catching the sunlight.

The bull saw him coming and wheeled to face this new challenge, this small figure approaching when everything else was running away.

Leviathan lowered its massive head, those 5-ft horns pointing forward like the lances of cavalry soldiers preparing to charge.

Foam dripped from its muzzle, and its eyes were wild, showing white around the amber irises.

Silas, no! The shout came from one of the other workers, a man Elellanena didn’t recognize, his voice high with fear.

But the boy kept walking as if he hadn’t heard, as if the entire world had narrowed down to just him and the bull.

He was talking now.

Eleanor could see his lips moving, though she couldn’t hear the words over the general commotion and the thundering of her own heartbeat in her ears.

He was maybe 20 ft from the bull now, then 15.

The distance closing with each careful step.

Leviathan poured the ground with one massive hoof, throwing up clouds of red Georgia dust that hung in the still air.

The animals entire body was tense like a spring wound too tight, every muscle visible beneath that mottled hide.

10 ft now.

Silas set the bucket down on the ground with careful deliberation and took two steps backward, his hands held out to the sides, empty and open, showing he carried no weapons, pose no threat, the bull stared at the boy with an intensity that seemed almost human in its focus, almost conscious in its calculation, and Eleanor realized with a strange detachment that she was watching someone who might be about to die.

and she couldn’t look away, couldn’t move, couldn’t even breathe properly.

The tension stretched like a wire pulled too tight, like a string on a violin tuned past its breaking point.

The entire yard had gone silent, every man frozen in place, afraid to move and break whatever spell was holding the scene together.

Even the other animals seemed to sense something.

The horses in the nearby stable going quiet.

The chickens in their coupe stopping their constant clucking.

Then Leviathan took a step forward.

Not a charge, just a step.

A single placement of one massive hoof.

Then another.

The bull moved toward the bucket, its eyes still fixed on Silus, watching for any sign of threat or deception.

Another step.

The distance closed to 8 ft, then six.

The massive head lowered toward the bucket and the bull began to eat, its teeth grinding the grain with a sound like millstones.

The men with ropes stood absolutely frozen, their mouths hanging open, afraid to breathe too loudly and break the moment.

Silas took another careful step backward, then another, creating distance while the bull was distracted and focused on the food.

He was letting Leviathan calm down while occupied with eating, using the animals own instincts to diffuse the situation.

It was working.

Elellanena released a breath she didn’t know she’d been holding, felt the tension in her shoulders begin to ease slightly.

And that’s when everything went catastrophically wrong.

One of the men with ropes, perhaps thinking the moment was right to secure the bull, perhaps simply panicking and acting without thought, threw his loop toward Leviathan’s horns.

The rope sailed through the air and slapped across the bull’s face with a sound like a hand striking flesh.

Leviathan exploded out of the bucket with a roar that Elellanena felt in her bones, a sound of pure betrayed rage.

The bull charged not toward the man with the rope who was already scrambling backward, but toward the nearest target, the figure that had been slowly retreating towards Silas.

The boy tried to run, but he was too close, had sacrificed distance for the sake of calming the animal.

Leviathan covered the gap in two enormous strides.

its head lowering, those massive horns swinging up in a motion designed by millennia of evolution to gore and toss and kill.

Silus jumped to the side at the last possible second, his body moving with the reflexes of youth and desperation.

The horn caught his shirt and tore it clean off his body, the fabric shredding like paper, but miraculously didn’t touch skin.

He hit the ground hard and rolled, scrambling on hands and knees to get away, to put distance between himself and death.

The bull wheeled for another pass, murder in its amber eyes, and Elellanena Callahan did something that changed the course of three lives forever.

She screamed.

It was a high, piercing sound of pure terror that cut through the chaos like a knife through silk, carrying across the yard with shocking clarity.

She hadn’t meant to make any sound at all, had been simply watching in frozen horror, but the scream tore itself from her throat without conscious thought or permission.

Leviathan’s head swiveled toward the new sound, the bull’s attention shifting instantly from the boy on the ground to this new stimulus.

The animal saw movement in the magnolia trees, something white and moving among the green shadows, something that fled.

Elellanena’s scream had been instinctive, but her flight was pure panic, the product of millions of years of prey evolution kicking in and overriding all rational thought.

She turned to run back toward the house, back to safety, but her skirts tangled around her legs, and her parasol fell from nerveless fingers.

Behind her, close enough that she could feel it in the ground beneath her feet.

She heard the thunder of hooves.

The bull was coming for her.

Leviathan crashed through the magnolia trees like they were grass, like they were nothing more than minor obstacles in the way of its rage.

Branches snapped and bark flew in all directions, and leaves rain down like green snow.

Elellanena could hear it gaining on her with every stride, could hear the wet rasp of its breathing, and the sound of its hooves hitting the earth like hammers.

She was going to die.

The thought came with absolute clarity and a strange calm that settled over her terror.

She was going to die out here in the garden she’d spent years cultivating, killed by an animal because she’d been stupid enough to scream to draw attention to herself.

Her foot caught on a root hidden beneath the grass and she fell, hitting the ground hard enough to drive all the air from her lungs in an explosive gasp.

She rolled onto her back instinctively, some part of her wanting to see death coming rather than take it in the back, and saw 2,000 lb of rage bearing down on her.

The bull was so close she could see individual details with terrible clarity, the blood red veins in the whites of its eyes, the foam and saliva dripping from its muzzle, the wicked sharp points of those horns that were about to punch through her body and pin her to the Georgia clay like a butterfly in a collector’s case.

Time slowed to individual heartbeats, to the space between seconds.

And Elellanena found herself thinking about her mother in Savannah, about the piano in the empty parlor, about all the things she’d never done and never would do now.

And then something slammed into Elellanena from the side with enough force to knock her sideways, driving her out of the path of Leviathan’s charge.

She caught a confused image of dark skin and terrified eyes, and realized it was Silus Bennett throwing his body between her and the bull, grabbing her around the waist with both arms and rolling them both toward the massive trunk of an ancient oak tree.

Leviathan’s horn caught Silas’s shoulder as they moved, the point slicing through skin and muscle, opening a gash that immediately welled with bright arterial blood.

But the boy’s momentum carried them clear of the main impact.

They slammed against the oak tree trunk as the bull thundered past.

Unable to stop its charge, its hooves tearing up great chunks of earth.

Elellanena lay on the ground with Silus’s body half covering hers, his blood dripping onto her white dress in spreading crimson flowers.

Her ears were ringing and her heart was trying to break through her ribs and she couldn’t seem to form a coherent thought beyond the simple fact that she was alive when she should be dead.

The boy pushed himself up on his arms, looking down at her with wide eyes that showed more white than brown.

“Ma’am, are you hurt? Ma’am, can you hear me?” His voice came from what seemed like a great distance, muffled and strange.

Elellaner couldn’t speak.

She could only stare up at this 16-year-old boy who had just risked his life to save hers, whose blood was dripping onto her dress from the wound in his shoulder, whose hands had touched her in ways that would scandalize every person on this plantation.

Behind them, Leviathan had wheeled around and was preparing for another charge, pouring the ground, lowering its head.

The bull had tasted violence now and wanted more, wanted to finish what it had started.

Stay down,” Silas said, his voice suddenly calm despite the terror Eleanor could see in his eyes.

He pushed himself to his feet, swaying slightly, and stepped away from Eleanor, putting his body between her and the charging bull once again.

What happened next would be told and retold in the quarters for years to come, growing with each telling until it took on the quality of legend, of myth, of something that couldn’t possibly be true, but was witnessed by too many people to deny.

Silus Bennett, shirtless and bleeding, his shoulder torn open and streaming blood down his chest, stepped away from the oak tree and walked directly toward the charging bull.

He spread his arms wide, making himself as large as possible.

And from somewhere deep in his chest, he produced a sound that Elellanena had never heard a human throat make before.

It was a roar, primal and terrifying.

The sound of a creature refusing to be prey, refusing to submit, refusing to die.

It carried across the yard and seemed to shake the very air, seemed to make the ground vibrate with its intensity.

and Leviathan impossibly, miraculously stopped.

The bull pulled up short, maybe 10 ft from Silas, its head swinging back and forth in confusion.

This prey that should run was instead advancing.

This small creature was making the sounds of a predator, of something that challenged rather than fled.

Silas held his ground, still making that terrible roaring sound, his arms still spread wide, his body language broadcasting dominance and threat and absolute refusal to yield.

The bull took a step backward, then another, the fight visibly draining from its massive body.

Silus advanced, still roaring, the sound continuous and unwavering, pulled from some well of courage or desperation that Elellanena couldn’t begin to understand.

Leviathan backed away from him, the rage fading from its eyes, replaced by something else.

Uncertainty, recognition.

This was the human who brought food and water.

The human who moved slow and safe.

The human who was part of the herd hierarchy.

The bull stopped retreating and simply stood there, its sides heaving with exertion, foam still dripping from its muzzle.

Silas stopped roaring.

He lowered his arms slowly, carefully, and took a deep breath that made his whole body shudder.

“Easy now,” he said, his voice returning to that familiar calm tone, despite the blood still streaming from his shoulder.

“Easy, Leviathan.

It’s done.

It’s over.

You’re all right now.” The men with ropes were approaching cautiously now, moving slowly, ready to act if needed, but clearly hoping they wouldn’t be.

Silas walked up to the bull and placed his hand on the massive head right between those deadly horns in a gesture of such casual bravery that it made Elellanena’s breath catch all over again.

Leviathan allowed the touch, even leaned into it slightly, seeking the comfort of familiar contact.

“Good boy,” Silas whispered so quietly that Elellanar almost didn’t hear it from her position on the ground.

“Good boy.

I know you’re scared.

I know it hurts.

We’re going to help you now.

He turned to look back at Elellanena, still on the ground by the oak tree, her white dress stained with dirt and blood, her hair fallen from its careful arrangement, her entire body shaking with reaction to what had just happened.

Their eyes met across the distance, and for a moment that stretched into something beyond time, they were just two people who had survived something terrible together.

Not mistress and worker, not white and black, not the carefully maintained categories and hierarchies that governed every aspect of southern life, just two humans who had looked at death and somehow impossibly lived to speak of it.

Then the moment shattered like glass under a hammer.

What in the name of God is happening here? Garrett’s voice cracked across the yard with the force of a thunderclap.

The overseer came running through the trampled Magnolia Grove, his narrow face purple with rage or heat or both.

His hand already moving toward the pistol at his belt.

He took in the scene with eyes that saw only what he expected to see, what he’d been trained by culture and prejudice to see.

Elellanena Callahan on the ground, her dress disarrayed and torn, her hair loose and wild, her pale skin marked with dirt.

Silus Bennett standing over her, shirtless and bloodied, close enough to touch her, his hands that had just been on her body still stained with her blood and his own.

The bull calm beside him.

The crisis apparently over.

Garrett’s hand closed on his pistol and pulled it from the holster in one smooth motion.

The gun came up and pointed directly at Silas’s chest, the barrel unwavering.

Step away from Mrs.

Callahan, boy, right now.

Do it slow.

Silus’s hands went up immediately in the universal gesture of surrender.

The movement so automatic it might have been carved into his bones after 16 years of surviving in a world where hesitation could mean death.

Sir, I was just trying to help her.

The bull was charging and I I said, “Step away.” Garrett’s voice rose to a shout, spittle flying from his lips.

“You think I’m blind? You think I can’t see what’s in front of my face? Silus moved back quickly, his hands still raised, his eyes fixed on the gun that could end his life with a single twitch of Garrett’s finger.

The other men were gathering now, drawn by the commotion, forming a rough circle around the scene.

White men from the fields, overseers and foremen, their faces hard with suspicion and anger.

They saw what Garrett saw.

They drew the same conclusions.

Garrett crossed to Eleanor and offered his hand, pulling her to her feet with exaggerated gentleness, making a show of his concern.

“Mrs.

Callahan, are you injured? Did he hurt you? Did that boy put his hands on you?” Eleanor was shaking.

The shock and terror of the last few minutes catching up with her all at once, making her legs weak and her thoughts scattered.

She opened her mouth to explain that Silas had saved her life, that the boy was a hero who deserved gratitude and reward, that he’d risked everything to protect her from the bull.

The words were right there, formed and ready to speak.

But before she could get them out, she saw something that made them die in her throat, like flowers touched by frost.

More men were arriving now, pulled from their work by the noise and excitement forming an ever larger circle around the scene.

White men with sunweathered faces and hard eyes, men who’d fought for the Confederacy and lost.

Men who’d owned other human beings and resented bitterly that they couldn’t anymore.

They were looking at Silas Bennett with expressions that Elellanena recognized from her years in the South, from countless social gatherings and conversations.

They saw what Garrett saw.

A black boy and a white woman in a compromising position.

Her dress torn and stained with blood.

His hands that had touched her body.

The truth didn’t matter to these men.

The actual events of the last 10 minutes didn’t matter.

What mattered was the story they would tell.

The conclusion they had already reached before asking a single question.

Before seeking any explanation, Elellanena felt the weight of that collective gaze like a physical thing pressing down on her shoulders.

She understood in that instant, with a clarity that was almost painful, what her silence would mean for Silus Bennett, but she also understood with equal clarity what the truth would mean for her.

If she told them what really happened, she would have to admit she’d been near the cattle pens when she had no business being there.

She would have to admit that her scream had provoked the bull’s charge, that she was responsible for the chaos and danger.

She would have to admit that a black boy had touched her, had grabbed her around the waist, had pressed his body against hers, had held her in his arms, even if only for seconds, and only to save her life.

even in gratitude, even in testimony to his heroism, the mere description of those facts would ruin her in ways she couldn’t fully articulate, but understood instinctively.

The other plantation wives would whisper about it at their social gatherings, their fans fluttering in front of their faces as they discussed in hushed tones how Elellanena Callahan had been handled by a negro boy.

Society would judge her, would find her somehow complicit, somehow to blame for allowing herself to be in a position where such a thing could happen.

Her reputation, the only currency she possessed in this world, would be shattered by the truth more surely than by any lie.

And Henry, what would Henry think, knowing that his wife had been held in a black boy’s arms, had felt his hands on her body? Would he believe it was innocent, necessary, heroic? Or would some part of him wonder, would some whisper of doubt poison their already distant marriage? Eleanor looked at Silas and saw the boy’s eyes pleading with her silently to speak, to tell them what had actually happened to save him the way he’d saved her.

She looked at Garrett, at the other white men, pressing closer at the gun still pointed at Silus’s chest.

She looked down at her own trembling hands stained with the boy’s blood that he’d shed protecting her.

And Eleanor Callahan, daughter of Savannah Society, wife of a plantation owner, keeper of all the rules that governed her narrow and carefully circumscribed life, made her choice.

It wasn’t a conscious decision so much as a surrender to forces larger than herself, to the weight of social expectations and the fear of consequences she couldn’t control.

I was walking in the gardens, she began, her voice barely above a whisper, each word feeling like a stone she was swallowing.

And the bull, it came through the trees.

It frightened me terribly.

Not exactly a lie, but not the truth either.

The truth bent and twisted to protect herself while throwing Silus to the wolves.

Garrett’s eyes narrowed, sensing something unspoken, some crack in the story he could wedge open.

Did this boy touch you, ma’am.

Did he put his hands on you? Say no.

A voice screamed in Elellanar’s head.

Just say no and this can all be over.

Deny it happened and save him.

But if she said no, how would she explain the blood on her dress? How would she explain being on the ground disheveled and terrified with Silus standing over her? The men had seen them.

They’d drawn their conclusions.

Denying the obvious would only make her look like she was hiding something worse.

He Elellanena’s voice broke and she hated herself for it.

Hated the weakness.

Hated what she was about to do.

He startled me.

Three words, just three simple words, not an accusation.

Exactly.

Not a direct claim that he’d done anything wrong, but not a defense either.

Not the testimony that could save him.

Three words that hung in the air like a noose waiting for a neck.

“He startled you,” Garrett repeated slowly, his voice dripping with satisfaction and a kind of vicious triumph.

He turned to look at Silas with an expression of pure malice.

“You hear that, boy? You startled Mrs.

Callahan.

What were you doing getting close enough to startle her? No, sir.

I was trying to help her.

The bull was charging right at her, and I pushed her out of the way.

Silus’s voice was desperate now, pleading, trying to make them understand.

“You shut your goddamn mouth,” Garrett snarled, taking a step toward him with the gun still raised.

“I saw you standing over her with my own eyes.

Saw you with your filthy hands on her.

You got some explaining to do, and it better be good.” The bull was charging.

I was trying to save her life.

Silas’s voice rose in desperation and fear.

The careful deference and submission cracking under the weight of injustice.

Garrett’s pistol came up higher.

The barrel now pointed directly at Silas’s face.

I said, “Shut your mouth.

You think we’re stupid? You think we don’t know what we saw? You were standing over a white woman with your hands on her body.

Now, I don’t care what story you want to tell, but that’s what happened.

Eleanor wanted to speak.

The words were there crowding her throat, demanding to be said.

He saved my life.

He’s a hero.

He did nothing wrong.

But her throat had closed completely.

Her voice was gone, stolen by fear and social conditioning and the terrible weight of consequences.

She stood there mute, a spectator to a tragedy of her own creation, watching as her silence condemned a boy who had risked everything to protect her.

The other white men had moved closer now, forming a tight circle around Silas, cutting off any possibility of escape.

The boy stood in the center with his hands still raised, blood still running down his chest from the wound in his shoulder that he’d gotten saving Eleanor’s life.

He looked at Elellanena one more time, his eyes holding no anger or accusation, just a terrible understanding that made her want to weep.

He knew what her silence meant.

He knew what was coming, and he knew there was nothing he could do to stop it.

“Get a rope,” Garrett said to one of the men, his voice calm now, business-like.

The voice of a man who’d done this before and would do it again.

“We’re going to sort this out proper once Mr.

Callahan gets back from town.

Until then, we make sure this boy don’t run off or try anything else stupid.

They bound Silas’s hands behind his back with rough hemp rope, tying the knots so tight his fingers went numb within minutes.

They marched him across the yard toward the old whipping post that still stood near the equipment shed, a thick post of seasoned oak that had been sunk deep into the ground during the days when such things were legal and ordinary and considered necessary for the maintenance of discipline.

It was still used occasionally for the worst offenses, though now it was done quietly without the public spectacle that had characterized the antibbellum period.

Elellanena watched them lead him away, his bare back straight despite everything, his head held high.

She wanted to run after them, to explain, to make this right, to undo the terrible thing her silence had done.

But her legs wouldn’t move.

Her voice wouldn’t work.

She stood frozen in place like a statue, a monument to cowardice and self-preservation.

Bessie appeared at her elbow, the older woman’s face grave with understanding and something that might have been pity.

Mrs.

Callahan, let’s get you inside now.

Get you cleaned up and proper.

You’ve had a terrible fright.

Elellanena let herself be led back to the house like a child.

Up the front steps, through the grand entrance hall, up the sweeping staircase to her bedroom.

Bessie helped her out of the ruined dress, brought warm water in a porcelain basin and soft cloths to wash away the dirt and blood.

“Don’t you worry about none of this, ma’am,” Bessie said quietly as she worked, her dark hands gentle on Elellanena’s pale skin.

“It’ll all get sorted out.

Mr.

Callahan will handle it when he gets back.” But Elellanena couldn’t stop worrying.

She moved to the window, still in her undergarments, and looked out over the plantation grounds.

through the wavy glass.

She could see the whipping post.

Could see Silas tied there in the full sun, still bare-chested, the wound in his shoulder, still bleeding slowly, the blood dark against his skin.

“Don’t you look at that, ma’am,” Bessie said gently, trying to guide Elellanar away from the window with soft hands on her shoulders.

“That ain’t nothing for you to see.

Ain’t nothing you need to concern yourself with.” But Elellanar couldn’t look away.

This was her doing.

Her silence had put him there.

The least she could do was witness what came next was bear the weight of watching what her cowardice had wrought.

She stood at the window in her undergarments, not caring about propriety anymore, and watched as Garrett paced in front of Silas like a predator circling wounded prey.

The overseer was waiting for Henry Callahan to return from town, building his case in his mind, preparing his story, deciding how to present this situation to maximum advantage.

A story where Silas Bennett was the villain instead of the hero.

A story where Eleanor’s silence had condemned a boy who had saved her life.

A story where truth mattered less than the preservation of the social order that kept white men in power and black men in chains.

Whether those chains were made of iron or debt, or the constant threat of violence, the afternoon sun beat down on the red Georgia clay with merciless intensity, the temperature climbing past 95°.

Silas stood tied to the post with no shade, no water, the sun baking his skin, and the flies swarming around the wound in his shoulder.

In the distance, thunder rumbled as a storm built over the western hills.

But it would arrive too late to provide any relief, too late to wash away what had been done on this terrible day.

Elellanena watched from her window and felt something break inside her, some foundation of her self-image cracking under the weight of what she’d done.

She’d always thought of herself as a good person, kind and compassionate, better than the cruel slaveowning society she’d been born into.

But when the moment came to prove it, when it cost her something to tell the truth, she’d failed completely.

She’d traded a boy’s life for her reputation, and both of them would have to live with that choice for whatever time remained to them.

Henry Callahan returned to his plantation at 4:00 in the afternoon, his carriage kicking up clouds of red dust on the long drive from town.

He’d spent the day negotiating with the banker about loans for the coming season, and had secured favorable terms.

He was in good spirits, thinking about the expansion of his cattle operation, about the money that Leviathan and his offspring would bring in over the coming years.

He noticed the unusual number of men gathered near the equipment shed as his carriage rolled past.

Noticed Garrett standing like a sentry near something at the center of the group.

Callahan climbed down from the carriage and walked toward the gathering with long strides, his boots crunching in the dry dirt.

“What’s all this?” he asked, his voice carrying the automatic authority of a man accustomed to command.

Garrett stepped forward, his face carefully arranged in an expression of concern and righteous anger.

Mr.

Callahan, sir, we’ve had an incident, a serious incident involving the bull and Mrs.

Callahan.

Callahan’s expression changed instantly, the good humor draining away.

Is Elellanena hurt? Where is she? She’s in the house, sir.

She’s shaken up, but not seriously injured, thank the Lord.

But there’s something you need to know about what happened.

Garrett proceeded to tell his version of the story, a carefully edited narrative that emphasized Silas standing over Ellaner with his hands on her that suggested impropriy and took advantage of the confusion that painted the boy as an opportunist at best and something worse at worst.

He made no mention of the bull charging Elellanor, no mention of Silus throwing himself between her and death, no mention of the heroism that had preceded the scene Garrett had witnessed.

Callahan listened with a face-like stone, his jaw muscles working, his hands clenching and unclenching at his sides.

When Garrett finished, Callahan walked over to where Silas was tied to the post.

The boy’s head came up as he approached, hope flaring briefly in his eyes before dying just as quickly.

“You’re going to tell me exactly what happened,” Callahan said, his voice dangerously quiet.

And you’re going to tell me the truth, boy, because I’ll know if you’re lying.” Silas took a breath, his throat dry from hours in the sun without water.

Sir, the bull broke free.

It was injured and wild.

It charged Mrs.

Callahan, and I pushed her out of the way.

I was trying to save her life, sir.

That’s all I was doing.

I swear it on my mother’s life.

Callahan studied him for a long moment, his eyes searching Silas’s face for deception, and you put your hands on my wife to do this? Yes, sir.

I had to.

The bull was going to kill her.

I pushed her toward the tree and took the hit on my shoulder instead.

Silas’s voice was steady despite his fear, speaking truth with the clarity of someone who had nothing left to lose.

Callahan looked at the wound on Silas’s shoulder, clearly from a horn strike, the kind of injury that supported the boy’s story.

He turned to Garrett.

You saw this happen? I saw him standing over her after, sir, with his hands on her.

She was on the ground, her dress all torn up.

He was shirtless and bleeding all over her.

Garrett’s voice was firm, stating facts while implying conclusions.

Did you see the bull charge her? Callahan asked.

Garrett hesitated for just a fraction of a second.

No, sir.

I came running when I heard the commotion.

But I saw what I saw after.

Callahan turned back to Silas.

My wife.

What did she say about what happened? Silus’s face twisted with something that might have been pain or might have been bitter understanding.

She said I startled her, sir.

Did you? Not on purpose, sir.

I was trying to save her life.

Callahan stood there for a long moment, clearly turning the situation over in his mind, weighing competing stories and trying to arrive at the truth.

He was a practical man, not given to hasty decisions that might cost him valuable property.

Silas was useful to him, saved him money, kept his expensive animals healthy.

But Eleanor was his wife, and there were social codes that had to be maintained regardless of practical considerations.

“Garrett, cut him down,” Callahan finally said.

Garrett’s face registered surprise.

“Sir, I said, “Cut him down.

I’m not going to beat a boy for saving my wife’s life, regardless of what it looked like.” Garrett’s face went red with suppressed anger, but he moved to obey, pulling a knife from his belt and sawing through the ropes that bound Silas to the post.

The boy’s arms fell to his sides, and he swayed slightly, his legs weak from standing in one position for hours.

“Thank you, sir,” Silas said quietly.

“I wasn’t finished,” Callahan cut him off.

“I believe you probably did save Elellanar’s life.

I believe that’s what happened based on the evidence.

But you put your hands on a white woman, boy.

You touched my wife and regardless of the reasons, regardless of the circumstances, that can’t stand.

Not here.

Not in Georgia in 1877.

Silas’s face went gray as he understood what was coming.

Sir, please.

I’m selling your contract to the Dade Cole Company, Callahan continued, his voice business-like now, discussing a transaction.

They’ve got a convict leasing operation up in the hills.

They’re always looking for strong young workers.

You’ll work off your father’s debt to me in the mines instead of on the land.

Consider yourself lucky that’s all I’m doing.

The convict leasing system.

Silas had heard about it in whispers from other workers.

Had heard the stories of men who went into the mines and never came out, who died in darkness and were buried in unmarked graves.

It was slavery by another name.

legal because the workers were technically convicts serving out sentences or working off debts.

The mines killed men slowly through lung disease or quickly through cave-ins and accidents.

The companies worked their least convicts to death because they had no investment in keeping them alive.

Could always get more to replace the ones who died.

Please, Mr.

Callahan.

Silas found his voice, desperation making him brave or foolish enough to beg.

Please don’t send me there.

I’ll work harder.

I’ll do anything.

I won’t never go near the house again.

Please, sir.

The matters decided, Callahan said flatly.

You’ll leave tomorrow morning.

Garrett will make the arrangements.

He turned and walked back toward the main house, his boots raising small clouds of dust with each step, leaving Silas standing there with Garrett and the other white men.

The overseer’s face split in a cruel smile.

Looks like you’re going down into the dark, boy.

Hope you like the smell of cold dust and the feel of a pick in your hands.

Because that’s all you’re going to know from here on out.

The men untied Silus completely and shoved him toward the quarters, telling him to get his things together to say his goodbyes to prepare for a journey he wouldn’t be returning from.

Silas walked back to the cabin he shared with his parents and sister, his legs moving automatically while his mind struggled to process what had just happened.

He’d saved a woman’s life and been condemned to a living death for it.

He’d done the right thing and lost everything.

Ruth was in the cabin when he arrived preparing the evening meal, and the wooden spoon fell from her hand when she saw his face.

Silas.

Baby, what happened? Your shoulder? They’re sending me to the mines, mama.

Silus said quietly, his voice hollow.

Mr.

Callahan selling my contract to the coal company.

Ruth’s hand went to her mouth, her eyes filling with tears.

She knew what that meant.

Everyone knew what that meant.

No, she whispered.

No, baby.

No.

What did you do? I saved Mrs.

Callahan’s life,” Silas said.

And then the story came pouring out of him.

The bull and the charge and Eleanor on the ground and his desperate attempt to protect her.

I did the right thing, Mama.

I did what anyone would do, and this is what I get for it.” Ruth pulled him into her arms, careful of his injured shoulder, and held him while he finally broke, while 16 years of holding everything in came pouring out in shaking sobs.

“This world ain’t right,” Ruth said quietly, rocking him like she had when he was small.

“This world ain’t fair, and it ain’t right.

But you listen to me, Silas Bennett.

You did the right thing.

You hear me? You saved that woman’s life, and that makes you a hero, no matter what they do to you.

After Moses came home from the fields an hour later and took the news in grim silence, his face aging 10 years in the space of a minute.

Maya, just 13 years old, cried into her mother’s skirts.

They sat together in that small cabin as the sun set, and the storm that had been building all day finally broke.

Rain hammering on the roof like nails being driven into wood.

Silas would leave in the morning, would be taken away in chains to the dade coal company mine 40 mi north in the hills.

He would descend into the earth and might never see daylight again, might never see his family again.

All because he’d been brave enough to save a life.

That night, Silas lay awake on his pallet and stared at the ceiling while rain poured down outside.

He thought about Leviathan, about the bull’s amber eyes and the understanding they’d reached.

He thought about animals and how they could be dangerous, but were never cruel, never punished you for things you didn’t do.

He thought about Elellanena Callahan and the look in her eyes when she’d chosen her reputation over his life.

and he thought about the darkness waiting for him in the mines, about the years of slavery by another name that stretched out ahead of him.

Something changed in Silas Bennett that night, something fundamental shifted in the foundation of who he was.

The boy who believed in doing right, who believed in helping others, who believed in the basic goodness of people, that boy died in the darkness of the cabin while the storm raged outside.

What remained was something harder, something that understood the world’s true nature, something that would survive whatever came next and remember every detail of the injustice done to him.

The morning came too quickly, gray and still raining.

Garrett arrived with two other white men and a set of iron shackles.

They chained Silas’s wrists and ankles, the metal cold and heavy, and loaded him into a wagon-like cargo.

Ruth and Moses and Ma stood in the rain, watching, their faces streaming with water and tears.

Silas looked back at them as the wagon pulled away, memorizing their faces, storing every detail in his memory because he didn’t know if he’d ever see them again.

The wagon rolled through the plantation gates and onto the road north toward the mountains, toward the mines, toward a darkness that would last for 2 years and transform whatever remained of Silus Bennett into something new.