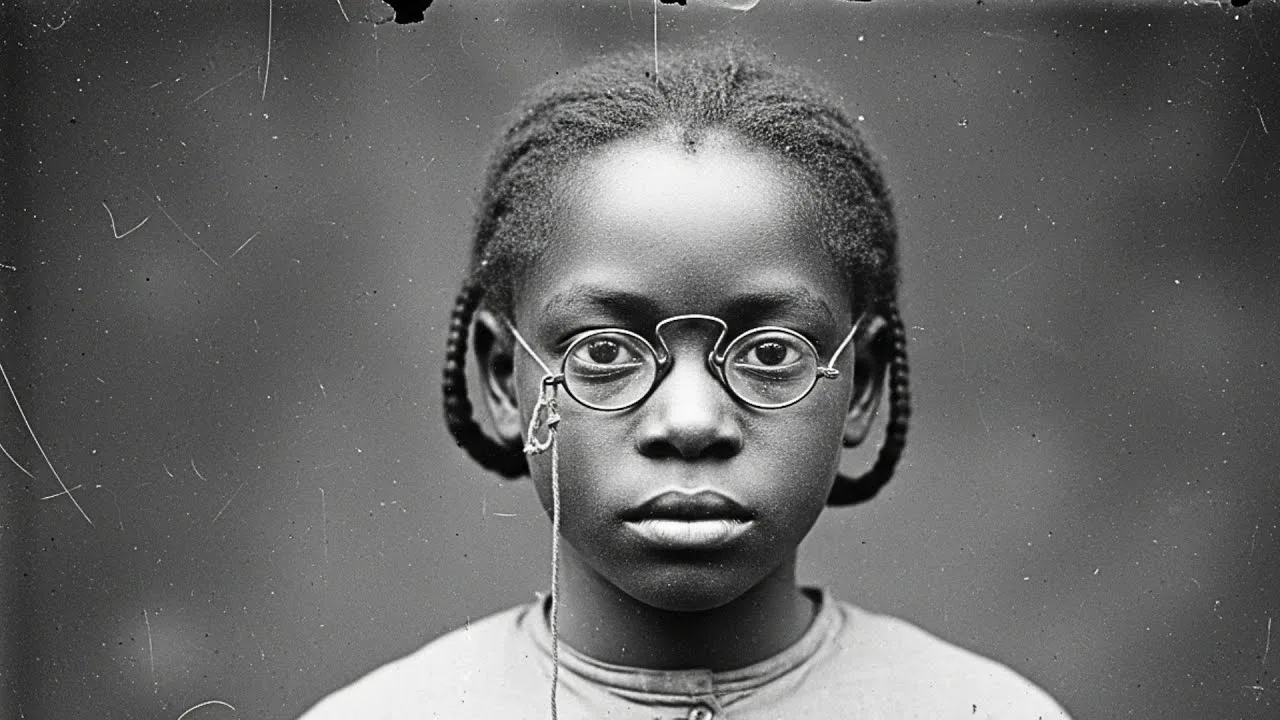

In the spring of 1865, as the war sputtered toward surrender and lawmakers hammered freedom into the Constitution, a seven-year-old Black girl in Wilkes County, Georgia began recalling the world with impossible precision.

They called her Sarah Brown.

Her mother said God had blessed her mind.

Her neighbors said she remembered like a bell rings—perfectly, every time.

Scientists would later call it eidetic memory.

Sarah simply called it seeing.

She was born in 1858, in a wooden cabin where winter crept through slats and summer pressed like a hand.

Her mother, Harriet, worked in the white house—carrying trays, stifling words, outfitting respect like a uniform.

Her father’s name didn’t make any ledger.

People whispered it might be the overseer.

Silence did the rest.

The plantation wasn’t a grand ocean of cotton, but a work camp for food and livestock that fed Confederate armies.

Meat and corn, tobacco for officers, fodder for horses.

The overseer counted hours, not souls.

The war frayed authority without changing cruelty.

Even as emancipation crept closer, every day still felt like the system could snap back, punishing anyone who mistook rumor for permission.

Then the map changed under everyone’s feet.

Sherman rolled through Georgia.

Columns moved like thunder.

The white family fled for a time.

Enslaved people stopped working or left for Union lines.

Freedom arrived first as practice, then as law.

Harriet and Sarah stayed.

Where would they go? Washington, Georgia—the county seat—filled with newly freed neighbors building a settlement out of prayer, scrap lumber, and will.

Harriet washed clothes until smoke and steam scalded her chest and lungs.

She scrubbed a living from other people’s dirt.

When she came home, her hands still shaped rest around her daughter.

She wanted something slavery had denied: letters that belonged to Sarah, numbers that bent toward her future, a mind free in a body that risked everything to stay alive.

Education meant dignity.

In a wooden church the community raised from scavenged boards, a Black teacher named Martha Williams lit candles against ignorance.

Martha had been born free in the North and educated by Quakers.

She came South because she believed learning could build a country from ruins.

Adults sat next to children.

Slates scraped.

Bibles lay open.

Words tried to do what whips had undone.

Sarah touched chalk one night and moved faster than anyone had seen.

Twenty-six letters in one lesson—forward, backward, scattered and reassembled.

Martha read a passage from the Gospel, and Sarah repeated it exactly—words, cadence, punctuation.

Martha wrote five words on the board, erased them, and asked what they were.

“In order: bread, sorrow, light, river, witness,” Sarah said, then pointed to where each had been on the slate as if the board still held the ghost of writing.

At first, Martha thought someone must have taught the child secretly.

Harriet shook her head.

“She hasn’t learned,” she said, meaning formally.

“She sees.” Martha tested gently, then rigorously: maps glanced for seconds and redrawn hours later, diagrams reproduced with shading perfect to the paper, lists of random numbers repeated forward, backward, or starting from the seventh item as if numbers were rivers and she knew each bend.

The community understood quickly what the world would take longer to admit: Sarah’s mind was a camera in an era before cameras were easy.

She didn’t memorize; she kept.

The elders smiled, then warned one another.

The danger wasn’t with her gift; it was with the attention it would draw.

For months, they kept her brilliance quiet, folding it into worship and school, letting families bring stories to be held by someone whose memory didn’t drop anything.

Then a federal man saw everything.

—

## The Doctor and the Stage

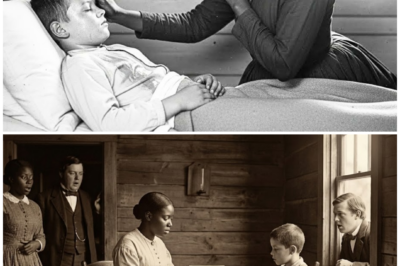

In the spring of 1866, a Freedmen’s Bureau physician arrived to examine freed people and write reports that would be read far away by men who had never sweated Georgia air.

He was Dr.

Charles Morrison, a Union Army surgeon from Pennsylvania, polite in the way men are when they don’t realize politeness is an instrument.

He attended Martha’s evening class.

He watched Sarah repeat text after seconds of exposure, reconstruct maps, recite numbers as if numbers had souls.

He asked Harriet permission to study Sarah.

“It’ll help prove your people’s capacity,” he said, meaning well like a man who believed science was neutral.

Harriet did not believe in neutral.

But refusal carried risks, and he promised she could be present, that tests would be local, that no harm would come, that science would honor the child.

He tested with medical textbooks and anatomical drawings, with newspapers and photographs, with lists that meant nothing except difficulty.

Sarah’s recall didn’t strain.

It held.

Dr.

Morrison wrote careful notes, measuring times, documenting line breaks and typographical errors Sarah reproduced exactly.

He meant to send articles to journals in Philadelphia and Boston naming “a Negro child of approximately eight years who demonstrates memory abilities beyond the literature.”

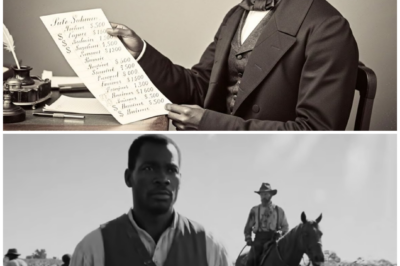

Then education turned into enterprise.

He saw audiences and tickets—curiosity wrapped in progress.

Posters appeared: “The Colored Girl Who Never Forgets.” Halls filled with men in coats and women in hats, clergy with notebooks and skeptics with folded arms.

Harriet sat near the stage, jaw set, watching her daughter perform her mind like a trick that wasn’t a trick.

The show was a machine.

Audience members held up newspapers and books; Sarah saw them for seconds, then repeated with precision you could fold and slice and still find perfect edges.

Dr.

Morrison spoke as if he were a bridge between wonder and explanation.

He speculated about brain mechanisms he couldn’t see and preached that Sarah proved “Negro intellect” in a way that might improve the present.

Admission turned into profit.

The money settled in Dr.

Morrison’s pockets, not Harriet’s.

When she resisted, he reminded her of the law’s thinness in a place where law had never held for Black people.

The audiences were split.

Some left changed—racist theories punctured by evidence that refused to cooperate.

Others left insisting the performance was fraud, because belief can armor itself against truth.

Some left muttering “unnatural,” measuring Sarah against a theology invented to protect hierarchy.

Ministers took turns with the pulpit.

Some called her memory a gift that proved equality.

Others called it demonic, proof that freedom had invited evil.

The sermons weren’t about Sarah; they were about control.

Memory became a battleground where both sides wanted God.

Then an evening in October shattered any pretense of entertainment.

An audience member brought a wartime newspaper page with an article about a 1863 lynching in Wilkes County—an enslaved man named Joshua hanged to terrify others.

Dr.

Morrison didn’t screen the text.

Sarah looked for five seconds and began to recite.

She then described the illustration: men surrounding the scaffold, faces carved into wood by someone who had stood close enough to see expressions.

Sarah named them.

Mr.

Patterson, who kept the store.

Mr.

Willis, the planter north of town.

Mr.

Carver, the sheriff.

Names met breath.

Men rose, swore, threatened.

A hall built for spectacle turned into a courtroom with no judge, a mob with no outside.

Dr.

Morrison whisked Sarah away as chairs scraped and anger scraped its way toward violence.

That night showed a fact the county already knew and hoped no one would say aloud: a girl who could not forget could not be controlled.

Sarah wasn’t entertainment; she was evidence.

Her memory preserved what white men needed buried for reconciliation’s comfort and the Lost Cause’s birth.

Threats followed.

Editors stopped writing.

Dr.

Morrison’s colleagues advised distance.

Local men visited quietly to insist the shows end.

He calculated risk as men who fear violence do—by retreat.

By March 1867, he left Georgia with his notebooks, his unsubmitted articles, his sudden silence.

He never published.

He filed Sarah away in a private archive where truth sometimes goes when truth is inconvenient.

—

## The Living Archive

Harriet and Sarah remained, more exposed than before, known now as carriers of unerasable testimony.

The community wrapped them in protection woven from prayer, watchfulness, and readiness.

In the summer of 1867, they moved to Augusta—larger, more anonymous, watched by some federal troops, sustained by a Black church whose doors rested on faith and hinges.

Reverend Thomas Wilson of the AME church heard Sarah’s story and understood the difference between spectacle and stewardship.

Under his protection, the child’s gift aligned with the community’s needs.

Freed families came with photographs of missing kin, names half-remembered, sale records thin as whispers.

Sarah listened, looked once, and kept.

She became a living repository: faces and dates, kinship and maps of loss.

Elders came to sit and speak.

They needed someone to hold their lives beyond bodies that were failing.

Sarah didn’t just record; she honored.

She remembered places where men buried Black bodies without markers.

She remembered contracts that bent numbers until labor turned into debt.

She remembered speeches intended to frighten and plans built to crush.

She remembered because forgetting was not in the vocabulary of her mind.

At Reverend Wilson’s night school, Sarah sped through the curriculum the way water flows downhill.

Reading and writing moved into algebra and Latin.

Geography took her around a world she could draw from memory.

History met a living archive and found itself measured.

By twelve, she was reading not just to know but to connect knowledge to truth stored in a child’s head.

White attention returned in 1870 in the language of medicine.

Doctors wanted to study Sarah’s brain to account for her abilities with theories that did not require admitting Black genius.

They proposed examinations, measurements, and—spoken aloud—an autopsy someday to understand “abnormalities.” They did not ask for consent as people ask equals.

Reverend Wilson and the community surrounded the church.

Legal arguments were made.

Muskets stood near doorframes.

The authorities backed away, measuring risk as men do when they weigh blood against paper.

Protection meant departure.

The South would not let Sarah simply be.

The AME network carried her north in 1871 to Philadelphia, to live with a church-connected family and to study at the Institute for Colored Youth, a rare place where Black minds were fed classics, calculus, languages—education intended to rearrange futures.

—

## In a City of Letters

In Philadelphia, Sarah’s talent lifted and hurt in equal measure.

Teachers watched an eighteen-year-old who could read a book once and recite it, solve a proof after a single demonstration, compose in Latin, answer in French, begin Greek as if grammar were a song she already knew.

Examinations bowed under scores that did not miss.

But perfect memory never sleeps.

It preserves joy; it also preserves knives.

Sarah could not forget slavery as others forget with time’s softening.

She could not forget threats, hands, nights when a mother had to pretend calm to think clearly while fear tried to tear her apart.

She could not forget a stage where men stood up and shouted danger at a child who named truth.

Sometimes in classroom light, she froze—eyes drawn inward, breath held—seeing scenes her mind had not laid to rest because laying to rest was not an option.

Teachers did not have language for trauma beyond moral comfort.

There was no therapy.

There was the incomparable relief of work and the undeniable weight of recollection that never blurs.

Sarah graduated in 1876 with an education beyond what the world intended for someone like her.

Records fall silent after that.

No marriage documents.

No teaching logs.

No death certificate with a neat line for cause.

Historians followed threads until threads ran out.

There are possibilities.

She could have died young—illness, despair—without a record connecting the loss to the child in Georgia whose mind held everything.

She could have chosen anonymity—new name, new city, a deliberate refusal to be extraordinary in public because extraordinary in public had meant danger.

She could have been taken, harmed, institutionalized by people who mislabeled memory as madness and turned suffering into a reason to disappear.

The silence is a wound you can trace but not close.

—

## Fragments That Refused to Burn

Pieces of her life remained in the places that built their own archives because official ones did not care to collect what did not serve them.

A photograph labeled “Memory Girl, Washington, Georgia, 1866” shows a child standing still before a wooden church, looking into the camera without flinch—eyes older than seven.

A letter from Martha Williams to a colleague in Philadelphia survives: “They fear what she remembers.

It is not the child they flee from.

It is the history she carries in her head.”

Reverend Wilson’s journal recorded in 1869: “She has become our living archive.

But she carries also a terrible burden, for she cannot forget the horrors she has witnessed.

I pray that her gift, which is also her curse, serves a purpose that makes her suffering meaningful.”

Church archives include a note: “We are sending you a child of exceptional gifts… She possesses perfect memory and has suffered greatly from those who would exploit such ability.”

Dr.

Morrison’s papers, never published, sat in a private collection until they did not.

His silence became part of the mechanism by which truth was held under water until the bubbles stopped.

—

## The Use of Forgetting

Sarah’s life forces a question that societies love to dodge: Who decides what is remembered? There is power in erasure.

Reconstruction required forgetting for white comfort—the smoothing of slavery’s violence into anecdotes, the refitting of Confederate motives into honor, the reframing of Black demands into threats.

A girl who could not forget was an interruption, a witness whose testimony refused to soften.

She should have been celebrated, protected, taught, asked what she wanted.

Instead she was displayed, threatened, exploited, then suppressed.

The lesson is not about the limits of her mind; it is about the limits of a country that could not tolerate a Black child with genius because her genius testified against its lies.

Eidetic memory remains rare and poorly understood.

Scientists can debate mechanics.

Communities know impact.

Memory can save families from losing themselves in the gaps.

Memory can also make the bearer suffer when pain refuses to blur.

The community tried to turn her gift toward preservation—faces and names held safe against fire and time.

That work mattered.

It seeded schools and stories in places where books were scarce and truth was under threat.

This is the part history too often refuses to honor: the labor of keeping memory alive when institutions try to bury it.

—

## What Remains

Sarah Brown’s story does not end cleanly.

The last page is missing, not because her life did not matter, but because records chose not to matter.

What remains is the proof that genius can be exploited and suppressed if it threatens power; the evidence that memory and truth are not neutral; the reminder that communities carry their own archives when official ones refuse.

Imagine her as a teacher somewhere, using recall to elevate children whose futures needed scaffolding.

Imagine her as a quiet clerk, storing histories for a congregation.

Imagine her as a woman who chose anonymity to survive, whose refusal to perform became an act of self-defense.

Imagine a grave without a marker in a city that did not know what it was burying.

Sarah’s gift was not merely a talent; it was a confrontation.

She showed that knowledge is dangerous when it contradicts comfort.

She showed that justice needs memory that endures past intimidation.

She showed that a single child can threaten a mechanism of forgetting designed to protect those who do harm.

She was a girl who could recite a page after seconds, who could draw a map from a glance, who could name the men in a woodcut of a lynching when they preferred to be unnamed.

She bore the cost of remembering in a country that loves the ease of forgetting.

If there is a prayer fit for her legacy, it is this: refuse amnesia.

Protect those whose gifts make truth unavoidable.

Build archives where families can find themselves.

Measure science by its ethics, not its curiosity.

Teach children that memory is a power, not a trap; that remembering can be a form of justice.

And when a story threatens the comfort of the powerful, ask whose comfort is being preserved at the cost of whose truth.

Sarah Brown could not forget.

May we choose not to.

News

She Was ‘Unmarriageable’—Her Father Gave Her to the Intelligent and Talented Slave, Virginia 1856

I was seventeen courtships into humiliation by the time my father made his most audacious decision. In Charleston parlors, they…

The millionaire master bought an enslaved woman for his son — what she did next no one ever forgot

Charleston woke humid and heavy, the kind of morning that stuck to skin and wouldn’t let go. Esther stood on…

The plantation owner handed his obese son over to the intelligent enslaved woman everyone was shocke

The Newse River crawled through the coastal plain, lugging silt and secrets. Tobacco leaves shimmered under a white sky. The…

Gideon Marshall the wisest slave in New Orleans, who deceived and destroyed seven plantation masters

There are stories that history tries to bury—too dangerous to tell, too unsettling to admit. They whisper a truth that…

Slave Finds the Master’s Wife Injured in the Woods — What Happened Next Changed Everything

The scream was so faint it could have been a fox, or a branch torn by wind. Solomon froze on…

The farmer promised his daughter to a slave if he planted 100,000 corn in 2 months—no one believed.

The summer heat in Franklin County, Georgia, did not simply sit on a man; it pushed. It pressed against lungs…

End of content

No more pages to load