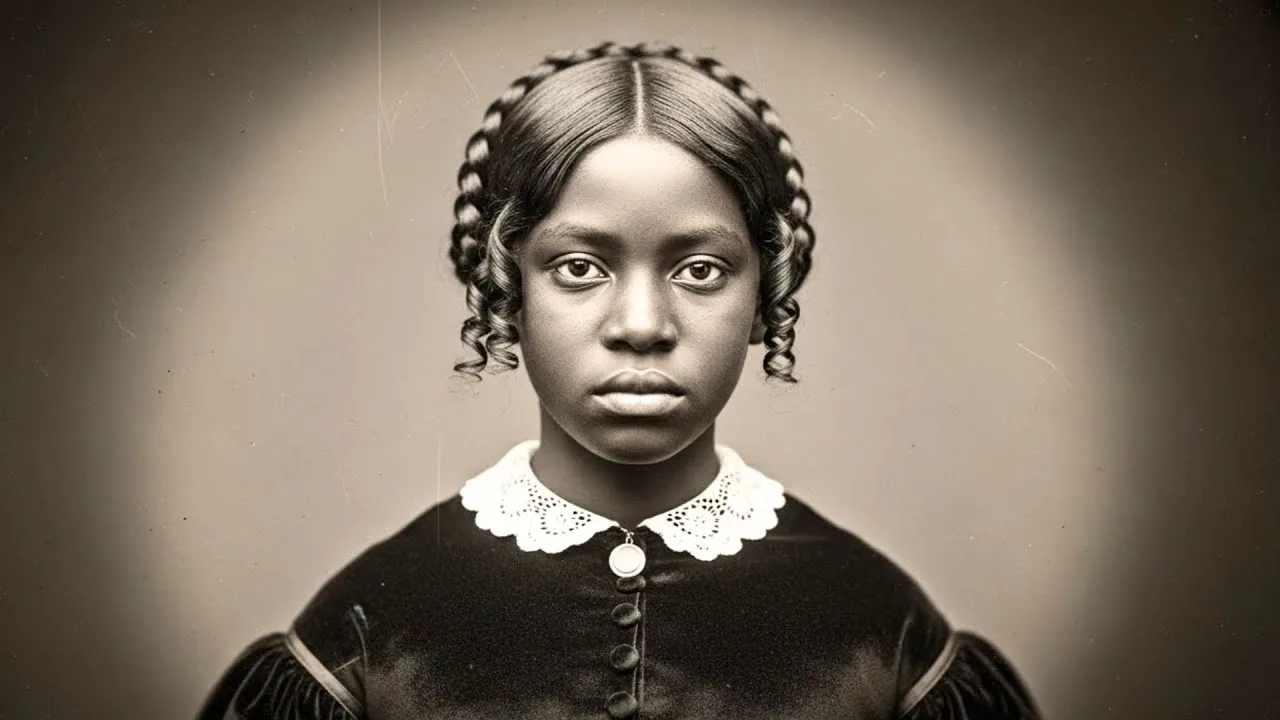

(1856, Sara Sutton) The Black girl who came back from the dead — AN IMPOSSIBLE, INEXPLICABLE SECRET

In 1856, a 9-year-old enslaved girl named Sarah Sutton was buried alive on a Mississippi plantation.

Three days later, she clawed her way out of her grave.

What happened next would turn Blackwood Plantation into the most feared place in the South.

A story whispered about but never spoken aloud.

A tale of death and vengeance that no one could explain and everyone wanted to forget.

This is that story.

August 1856, Blackwood Plantation, Mississippi.

The heat was like a living thing, pressing down on everything, making it hard to breathe, hard to think, hard to survive.

The cotton fields stretched out white and endless under a sky so blue it hurt to look at.

300 acres of wealth built on the backs of people who owned nothing, not even themselves.

The plantation belonged to Margaret Sutton, a widow of 48 who had inherited it when her husband died in 1852.

Margaret was tall and thin with gray eyes that never seemed to blink and a mouth that rarely smiled.

She ran the plantation with an iron fist, determined to prove that a woman could manage such an enterprise as well as any man, better even.

She kept detailed records of every expense, every bail of cotton, every enslaved person and their value.

To Margaret, the plantation was a business.

The people who worked it were inventory, nothing more.

Before we continue with this incredible story of Sarah, don’t forget to comment which city you’re listening from and subscribe to the channel.

Your support is what keeps these stories alive.

Let’s continue.

In 1856, a healthy adult male slave was valued at approximately $1,200.

A strong woman might be worth $800 to $1,000.

Children were valued lower, their price increasing as they grew and proved they could work.

Margaret’s ledger listed Sarah Sutton at $250, less than a quarter the value of an adult worker.

Margaret considered this generous.

Most plantation owners valued sickly children at $100 or less.

Some would have sold Sarah South to the sugar plantations of Louisiana, where life expectancy was measured in years, not decades, where workers died so fast they had to be constantly replaced.

Sarah Sutton carried Margaret’s last name not through any family relation, but through ownership.

She was born on the plantation in 1847, the daughter of a woman named Ruth, who had been valued at $900 in Margaret’s husband’s ledger.

Ruth died, bringing Sarah into the world, reducing the plantation’s assets by $900 and adding only $250 in return.

From a business perspective, Sarah’s birth was a net loss of $650.

Margaret’s husband had noted this in his records with obvious displeasure.

From her first breath, Sarah was marked as different.

She was small, even for a baby, weighing barely 5 lb.

She grew slowly, stayed thin no matter how much she ate.

Her skin was lighter than most of the other enslaved children, suggesting her father was white, though no one ever spoke about who he might have been.

Some whispered it was Margaret’s late husband, but those whispers never lasted long.

Dangerous questions had a way of getting people sold or worse.

By age nine, Sarah stood barely 4t tall and weighed maybe 50 lb.

She looked more like six than nine.

Her eyes were large and dark, too old for her face, like she had seen things no child should see.

She rarely spoke.

When she did, her voice was so quiet people had to lean in close to hear.

She never played with the other children, never ran or laughed or sang the songs they sang in the quarters at night.

She just worked slowly and carefully and stayed as invisible as possible.

Margaret called her the weak one and noted in her ledger that Sarah’s value might need to be adjusted downward to $150 if she didn’t improve.

The overseer, a brutal man named Coleman Briggs, called her dead weight and worse things.

Briggs was 35, built like a bull with hands that had broken bones and a whip he used too often.

He earned $60 a month plus room and board, making him one of the highest paid overseers in Yazoo County.

He had worked at Blackwood for 6 years, earning his position through cruelty and efficiency.

Briggs believed enslaved people were animals that needed to be broken, and he took pride in his ability to break even the strongest spirits.

He had developed a reputation across three counties as an overseer who could make any plantation profitable by squeezing maximum productivity from workers.

His methods were brutal but effective, at least in the short term.

In his six years at Blackwood, cotton production had increased by 40%.

that he had also buried 23 workers, including seven children, in that same period was considered an acceptable cost of doing business.

But Sarah confused him.

You couldn’t break someone who never fought back.

You couldn’t instill fear in someone who already seemed terrified of everything.

You couldn’t motivate someone who seemed to have given up on life before it even started.

So he just made her work harder.

Pushed her past what her small body could handle, hoping she would either toughen up or die.

He didn’t care which.

In his mind, she was a waste of food and resources, consuming more than she produced, dragging down the plantation’s overall efficiency.

The other enslaved people at Blackwood watched Sarah with a mixture of pity and frustration.

An old woman named Esther, who had been at the plantation for 40 years and was now valued at only $150 due to her age and declining strength, tried to look after Sara when she could.

Esther had been purchased in 1816 for $600, considered prime breeding stock at age 20.

She had given birth to 11 children over 25 years.

Eight had been sold away.

Three had died in childhood.

She had earned the plantation thousands of dollars in value through her children.

Yet now that she was old and worn out, she was worth barely more than the sickly child she tried to protect.

Esther would sneak Sarah extra food when possible, though food was carefully rationed and monitored.

Workers received approximately one pec of cornmeal per week, 3 to four lbs of salt pork or bacon, and occasional supplements of molasses or vegetables.

This diet, calculated to cost the plantation about 20 cents per person per day, was designed to provide just enough calories to keep workers functional but not comfortable.

Esther would give Sarah portions of her own rations, help her with the harder tasks when no one was watching, hold her at night when Sarah woke up screaming from nightmares she never talked about.

Esther said Sarah reminded her of a bird with a broken wing, still alive but unable to fly, just waiting for something to end its suffering.

She told the other women in the quarters that Sarah wouldn’t live to see 15.

The girl was too weak, too fragile, not meant for this world.

Better she go to God sooner than later before life broke what little spirit she had left.

The other women would nod sadly, having seen too many children die to argue with this logic.

In their experience, death was sometimes the kindest thing that could happen to an enslaved child.

There was a young man named Daniel, maybe 20 years old, valued at $1,200 in Margaret’s ledger.

He was strong and smart, worth his high price, with years of productive labor ahead of him.

He had been born on the plantation, son of two valued workers, and had grown into exactly the kind of asset Margaret prized.

He could pick 200 lb of cotton a day in peak season.

He could repair equipment.

He could read numbers and keep basic records, making him useful for more than just field work.

Daniel often worked near Sarah in the fields.

He would try to help her, carry her cotton sack when it got too heavy, take over her row when she fell behind.

But Briggs noticed everything and helping someone else meant both people got punished.

Briggs understood that solidarity among enslaved people was dangerous.

Workers who helped each other might start thinking of themselves as a community with shared interests rather than as individual assets.

So he made sure to crush any signs of cooperation to keep everyone isolated and afraid.

Still, Daniel tried.

He couldn’t help himself.

Something about Sarah’s quiet suffering touched something in him, made him angry at the injustice of it all in a way that was dangerous for an enslaved man to feel.

His mother had told him to keep his head down, to be grateful he was healthy and strong, to not waste emotion on things he couldn’t change.

But watching Sarah struggle day after day, watching this child work herself to death for people who saw her as worth less than a decent horse, made him want to fight back in ways that would get him killed.

The cotton harvest season ran from August through October.

This was the busiest and most important time of year for Blackwood Plantation.

The entire year’s profit depended on getting the cotton picked, processed, and shipped to market.

In 1856, cotton sold for approximately 11 per pound.

A good worker picking $150 per day generated about $16.50 worth of cotton per day.

Over a 90-day harvest season, that single worker could produce almost $1,500 in revenue.

Subtract the annual cost of feeding, housing, and clothing that worker, approximately $73, and the profit margin was clear.

This is why plantation owners pushed workers so hard during harvest.

This is why they calculated everything down to the penny.

This is why a child like Sarah, who could only pick 30 or 40 a day, generating maybe 3 or4 worth of cotton daily, barely covering her own maintenance costs, was seen as a liability.

In the cold mathematics of slavery, she didn’t make economic sense.

She was inventory that wasn’t appreciating in value, that was actually costing more to maintain than she produced.

Each enslaved person at Blackwood was expected to pick between 150 and 200 lb of cotton per day.

Adults who picked less faced punishment, usually whipping, sometimes worse.

Briggs kept careful records, weighing each person’s cotton at the end of each day, recording the amounts, comparing them to quotas.

Those who exceeded their quotas occasionally received small rewards, an extra bit of food, a Sunday afternoon off, a word of praise.

Those who fell short faced consequences that escalated with each failure.

Children under 10 were expected to pick at least 75 per day.

Sarah had never once met this quotota.

On her best days, she managed maybe 40.

Most days, it was closer to 30.

Every day she fell short.

Margaret docked her food rations by an amount proportional to her shortfall.

If she picked £40 instead of 75, she received about half rations that night.

The logic was simple.

If you don’t produce enough to justify your food, you get less food.

That this created a downward spiral where underfed workers became weaker and less productive, which led to more food reduction, which led to more weakness.

didn’t concern Margaret.

The weak were supposed to die.

That was nature’s way.

That was how you bred strong stock.

Briggs added punishments of his own.

He would make Sarah work through the meal breaks.

Would assign her to the hottest, most difficult rouse, would stand over her criticizing, mocking, sometimes cuffing her on the back of the head when she was too slow.

He told her she was worthless, that she was stealing from the plantation, that she should be grateful Mrs.

Sutton didn’t just sell her to the sugar fields where she would be dead in a year.

August 15th, 1856 started like any other day.

The sun rose hot and angry, the sky already bright at 5:00 a.m.

when the bell rang, calling everyone to the fields.

Sarah dragged herself out of the small cabin she shared with Esther and five other women.

The cabin measured approximately 16x 20 ft, housing seven people.

Each person had about 46 square ft of space, roughly equivalent to a modern prison cell.

The cabin had no windows, just gaps in the walls for ventilation.

No furniture except for rough sleeping platforms, no privacy, no comfort.

Sarah hadn’t slept well.

She never slept well.

Her body hurt all the time now.

A constant ache in her bones and muscles that never went away.

She was coughing more lately, a dry hack that made her chest hurt and brought up flexcks of blood sometimes.

Esther said it was the cotton dust.

Said lots of children got sick from breathing it in day after day, year after year.

The tiny fibers got into your lungs and never came out, causing constant irritation and infection.

Some people got better.

Most didn’t.

Esther had seen it happen dozens of times over 40 years.

A child would start coughing, would get weaker, would waste away over months or years until they just stopped breathing.

One day, Sarah stumbled out into the pre-dawn darkness and joined the line of people walking to the fields.

Nobody talked much in the morning.

Everyone was too tired, too hungry, too focused on getting through another day.

They walked in silence, ghosts moving through the gray light, heading toward another day of brutal labor under a brutal sun for the benefit of people who saw them as livestock.

By noon, Sarah had picked maybe 15 lbs of cotton.

Her small fingers, cut and bleeding from the sharp cotton bowls that tore skin with every handful, moved as fast as she could make them move, but she was so slow.

Each bowl required both hands to open to extract the cotton without leaving pieces behind to stuff it into the sack that dragged behind her growing heavier with each row.

Her back screamed with pain from bending over constantly.

The sun was merciless, beating down with a heat that made the air shimmer and dance.

She had been given one cup of water at sunrise and wouldn’t get another until sunset 12 hours later.

This was standard practice during harvest season.

Water breaks took time away from picking.

Margaret had calculated that allowing water breaks reduced daily productivity by approximately 8%.

Therefore, workers got water twice a day, morning and evening, and were expected to manage.

That people sometimes collapsed from heat and dehydration was regrettable but acceptable.

The cost of lost productivity from water breaks was higher than the occasional cost of a dead worker.

Sar’s mouth was so dry, her tongue stuck to her teeth.

She felt dizzy, like the world was tilting, like the ground wasn’t quite where it should be.

Her vision kept blurring.

She had to stop and close her eyes, breathe deep, fight the urge to just lie down in the dirt and not get up.

But lying down meant punishment.

meant Briggs would come with his whip or his fists meant less food tonight.

So she kept working, kept picking, her small hands moving slower and slower as the heat and exhaustion took their toll.

Briggs rode through the fields on his horse around 100 p.m.

checking on workers, counting filled sacks.

He carried a small scale, would randomly weigh sacks to make sure people weren’t padding them with dirt or rocks, something desperate workers sometimes tried.

He also carried his whip coiled on his saddle and a pistol on his hip.

The pistol was loaded.

He had used it twice in 6 years, shooting workers who tried to run.

Both had died.

Both deaths were ruled justified self-defense.

A slave trying to escape was legally considered to be stealing themselves, and deadly force to prevent theft was permitted.

When Briggs got to Sar’s row, he dismounted and grabbed her nearly empty sack.

He weighed it in his hand, his face darkening.

£15? In 8 hours, you picked 15? His voice carried across the field, loud and angry, meant to be heard by everyone.

Other workers stopped to watch, dreading what would come next, but unable to look away.

They had seen this scene before many times with different children.

It always ended the same way.

Sarah stared at the ground, swaying slightly.

She whispered, “I’m sorry, sir.

I’m trying my best.” Her voice was so quiet Briggs had to lean in to hear it.

This made him even angrier.

He hated when they were submissive like this when they wouldn’t even fight back enough to make punishment satisfying.

Your best.

Your best is £15.

You know what you cost this plantation? You know what Mrs.

Sutton pays to feed your worthless mouth? He grabbed her arm and yanked her upright, shaking her.

20 cents a day.

That’s what it costs to keep you alive.

20 cents a day for food and housing and the clothes on your back.

You know what? 15 lb of cotton is worth $1.65.

You know how many days it takes you to earn enough to pay for one day of food? About 8 days.

You’re stealing from this plantation.

You’re stealing food from people who work hard, who earn their keep.

You’re a thief.

The math was accurate, but deliberately misleading.

It didn’t account for the fact that Sarah had been forced into this work, that she was 9 years old, that she was sick and underfed.

It didn’t account for the fact that she never asked to be born into slavery, never agreed to this arrangement, had no choice in any of it.

But none of that mattered to Briggs.

In his worldview, enslaved people existed to produce profit.

Those who didn’t produce enough had no value and therefore no right to complain about their treatment.

Briggs dragged Sara to the center of the field where everyone could see.

This was standard practice.

Punishment was meant to be public, to serve as a warning to others, to maintain fear and control.

He pulled out his whip, a braided leather thing about 5 ft long that could strip skin from flesh with a single strike.

Maybe pain will motivate you.

Maybe if your back hurts more than your arms, you’ll work faster to make it stop.

Esther started forward from where she had been working three rows over, but Daniel grabbed her arm, held her back.

His eyes were full of pain, but he shook his head.

Getting involved would just mean two people getting whipped instead of one.

Or worse, they had all learned this lesson before.

You couldn’t save everyone.

Sometimes you couldn’t save anyone.

All you could do was survive and hope tomorrow would be better.

though it rarely was.

Briggs raised the whip high, his arm pulling back for maximum force.

Sara stood very still, not running, not crying, just waiting for the pain she knew was coming.

She had been whipped before many times.

She knew what it felt like.

How the skin would split and burn.

How the blood would run down her back.

how she would have to sleep on her stomach for days while the wounds tried to heal, often getting infected in the dirty conditions of the cabin.

She knew all of this and accepted it because what choice did she have? But before Briggs could bring the whip down, Sarah collapsed.

She just fell to the ground like someone cut her strings like a puppet with no one to hold it up.

Her eyes rolled back in her head, showing only whites.

Her body went completely limp, folding in on itself as she crumpled into the dirt.

She didn’t catch herself, didn’t put her hands out, just fell like a dead thing.

Brig stood there for a moment, whip still raised, confused by this development.

He kicked her with his boot, not gently.

Get up.

Get up right now, or I’ll make it worse.

I’ll whip you until you can’t walk.

But Sarah didn’t move.

Didn’t respond at all.

Her chest was moving but barely.

Shallow breaths that seemed too weak to sustain life.

Her skin was pale, almost gray.

Her lips were turning blue.

Daniel broke free from his row and ran over before anyone could stop him.

He knew he would be punished for this, but he didn’t care.

He knelt beside Sarah and put his hand on her chest, feeling for her heartbeat.

It was there, but wrong, irregular, and weak like it might stop at any moment.

She’s not breathing right.

Something’s really wrong with her.

She needs the doctor.

She’s really sick.

Briggs kicked Daniel hard in the ribs, knocking him aside.

Get back to work or you’ll join her on the ground.

But Daniel stayed where he was, protecting Sarah’s body with his own.

She’s dying.

Can’t you see that? She’s dying right here in the dirt.

At least let her die somewhere with shade.

At least give her that much.

Briggs looked at Sara’s still form and cursed under his breath.

If she died in the field from a whipping, there would be questions.

Margaret didn’t like losing property, even worthless property worth only $250.

There would be investigations, reports, maybe problems with the law.

If someone made a fuss about it, better to let the doctor deal with it.

Let her die somewhere out of sight, somewhere the blame could be deflected.

He called for two other workers to carry Sarah to the plantation house.

Take her to Dr.

Merritt.

Let him figure out what’s wrong with her.

And you, he pointed at Daniel.

Get back to work.

I’ll deal with you later.

Daniel watched as they carried Sarah away.

Her small body so light she looked like she weighed nothing at all, like she was already a ghost.

He had a terrible feeling he would never see her alive again.

The plantation doctor was a man named Thomas Merritt, 72 years old, who had been practicing medicine for 40 years.

He charged Margaret $30 per year to be on call for medical issues at Blackwood.

This worked out to about 8 cents per day, making him one of the cheaper expenses of running the plantation.

It was easy money for minimal work.

Most of his treatments involved bleeding patients, which required no expensive medicines, or giving them lordinum, which cost about $2 per bottle and could be stretched for months.

Dr.

Merritt wasn’t particularly skilled, having received his medical training through a brief apprenticeship 30 years earlier rather than formal schooling.

But in rural Mississippi in 1856, skilled doctors were rare and expensive.

Doctors who would treat enslaved people at all, were even rarer.

Most proper physicians considered it beneath them to treat slaves, seeing it as veterinary work rather than real medicine.

So plantation owners made do with men like merit, who asked few questions, kept poor records, and didn’t care if their patients lived or died.

They laid Sarah on the floor of the doctor’s room in the main house.

Not on a bed or examination table, just the floor.

The bed was for white patients.

The floor was sufficient for enslaved people.

Doctor Merritt examined her briefly, his movements slow and careless.

He checked her pulse by pressing two fingers against her wrist.

It was there, but weak and irregular, sometimes seeming to stop for several seconds before starting again.

He listened to her chest by pressing his ear against her rib cage.

He heard fluid in her lungs, a wet rattling sound that indicated pneumonia or something similar.

He pulled back her eyelids and saw her eyes had rolled back, showing mostly white with just a sliver of brown visible.

He checked her temperature by pressing his hand against her forehead.

She was burning with fever, her skin hot and dry.

He checked her hands and feet and found them cold, the blood retreating from her extremities as her body tried to preserve her core.

This was a bad sign.

It meant her body was shutting down, prioritizing vital organs over everything else, a desperate measure that often preceded death.

Margaret stood in the doorway watching, her arms crossed, her face showing irritation rather than concern.

This was an inconvenience, an interruption to her day.

Well, what’s wrong with her? Dr.

Merritt stood up slowly, his knees creaking with age.

She has pneumonia, I believe.

Her lungs are full of fluid.

Combined with exhaustion, dehydration, malnutrition, and heat exposure, her body is failing.

She’s in what we call systemic collapse.

Multiple organ systems shutting down simultaneously.

Margaret’s face showed no emotion.

She had heard similar diagnosis before.

Workers died regularly on plantations.

It was a normal part of doing business.

Can you fix her? The question was asked the same way she might ask if he could fix a broken tool.

Dr.

Merritt shrugged, wiping his hands on his pants.

I can try, but honestly, Mrs.

Sutton, I’m not confident it would be successful.

The medicine alone would cost about $5.

Quinine for the fever, ldinum for the pain, perhaps some stimulants to strengthen her heart.

The nursing care would take time away from more valuable workers.

Someone would have to sit with her, give her water, keep her cool, monitor her condition.

That’s lost productivity.

He paused, doing his own calculations.

And even with treatment, I’d say her chances of survival are less than half.

probably closer to one in three.

She’s been weak her whole life.

This might just be nature taking its course.

Sometimes the weak ones need to die so resources aren’t wasted on them.

That’s just how the world works.

Margaret did the math in her head quickly.

$5 for medicine, perhaps another $5 in lost productivity from whoever had to nurse Sarah.

$10 total to maybe save a girl worth $250.

but only if she recovered fully and became a productive worker, which seemed unlikely given her history.

If she recovered but stayed weak, she might never be worth more than $150 or even $100, making the investment a loss.

And there was a two in three chance she would die anyway, making the entire $10 wasted.

The smart business decision was clear.

Margaret had built Blackwood’s profitability by making smart business decisions, by not letting sentiment interfere with economics.

Don’t waste the medicine, she said.

Her voice was firm, final.

Make her comfortable.

If she dies, she dies.

God’s will.

This was a common phrase among slaveholders, attributing deaths to divine providence rather than their own decisions.

It made it easier to live with.

Dr.

Merritt nodded.

He had expected this answer.

He had given similar advice dozens of times, and Margaret had always taken it.

Why waste resources on a failing asset? Better to cut your losses.

He gave Sarah a small dose of Lordum, maybe a quarter teaspoon, just enough to dull her pain slightly, but not enough to waste valuable medicine on someone unlikely to survive.

Then he left her lying on the floor and went to have his dinner.

It was 3:00 in the afternoon on August 15th, 1856.

By 6:00 p.m., An Sarah’s condition had worsened significantly.

Her fever had spiked higher, her skin now so hot it was almost painful to touch.

Her breathing had become even more shallow and irregular, sometimes stopping completely for 10 or 15 seconds before starting again with a wet, rattling gasp.

She hadn’t regained consciousness.

She hadn’t moved at all except for occasional twitches and convulsions as her body fought its losing battle.

Dr.

Merritt checked on her once more around 700 p.m.

and shook his head with certainty.

She’ll be gone by morning, probably much sooner, maybe an hour or two at most.

He told Betty, one of the house servants valued at $600, who served as a maid and occasional nurse, to watch the body and let him know when Sarah passed so he could sign the death certificate.

Betty sat on a stool in the corner, watching this child die, feeling helpless and sad, but not surprised.

She had watched many people die over her 30 years at Blackwood.

Death was common here, expected, almost routine.

At 8:35 p.m., Sarah Sutton stopped breathing.

Her chest, which had been moving in those shallow, irregular breaths, went still.

Betty waited a full minute watching, but there was no movement.

She called for Dr.

Merritt, who came down grumbling about being interrupted during his evening reading.

He checked for a pulse in Sarah’s wrist.

Nothing.

He held a small hand mirror to her mouth, watching for fog from breath.

The mirror stayed clear.

He pressed his ear to her chest, listening for a heartbeat.

Complete silence.

Dr.

Merritt pronounced Sarah dead at 8:35 p.m.

August 15th, 1856.

cause of death, pneumonia complicated by chronic weakness and multiple contributing factors.

He recorded it carefully in his medical ledger where he kept records of births, deaths, and treatments at Blackwood.

Sarah Sutton became entry number 437 in that ledger, one of 38 deaths he had recorded in his 6 years serving the plantation.

Most were children or elderly slaves.

A few were adults who had been worked to death or died from accidents or disease.

All were noted with the same clinical detachment, just facts and figures, dates and causes.

Margaret was informed while she ate her dinner.

She barely looked up from her roasted chicken and vegetables.

Have them bury her behind the barn.

No point wasting space in the cemetery, and do it quickly.

This heat will make the body deteriorate rapidly.

This was not unusual.

Enslaved people who died were often buried quickly in unmarked graves, especially children, especially sick ones who hadn’t been productive.

They weren’t considered worthy of the space or ceremony afforded to white people or even to valuable adult slaves who had earned some measure of respect through years of hard work.

The cemetery Margaret referenced was reserved for white people and occasionally for extremely valuable or long-serving slaves who had been favorites of the family.

It had proper headstones, maintained plots, regular care.

The area behind the barn was different.

It was where dead animals were buried, where broken equipment was discarded, where anything considered waste was dumped and forgotten.

Burying Sara, there was a final insult, a last statement about her worth.

Coleman Briggs was given the task of organizing the burial.

He picked two workers, James and Moses, gave them shovels, and told them to dig a hole 4 ft deep behind the barn.

He didn’t provide a coffin.

Coffins cost money, at least $5 to $10, for even a basic pine box.

That was money Margaret wouldn’t waste on a child who had cost the plantation more than she produced.

He just had them wrap Sarah’s body in an old piece of canvas that had once been used to cover cotton bales, but was now too damaged to be useful.

The burial took less than an hour.

James and Moses, both men in their 30s, dug the grave in silence, working quickly in the fading light.

They had buried people before, too many people.

The ground behind the barn was soft from previous burials, easy to dig.

They dug down about 4 ft, creating a hole roughly 6 ft long and 2 ft wide, just barely big enough for Sar’s small body.

They placed her in the ground, still wrapped in canvas, her face covered.

No ceremony, no prayers, nothing.

Briggs wouldn’t allow it.

Religious services for slaves had to be approved and supervised, and he wasn’t going to waste time on a child who had been more trouble than she was worth.

James and Moses filled the dirt back in, covering Sarah’s body, patting it down flat.

By 10 p.m., it was finished.

Sarah Sutton was in the ground, 4 ft of Mississippi dirt between her and the world, forgotten before the dirt had fully settled.

Esther watched from the quarters, tears running down her face.

She had wanted to say goodbye, wanted to wash Sarah’s body properly according to the traditions her own grandmother had taught her, wanted to say a prayer over her grave.

But she hadn’t been allowed.

None of the enslaved people had been allowed to participate in the burial.

It was done quickly, efficiently, without sentiment or respect.

Just another dead slave, another loss to be noted in the ledger and forgotten.

Daniel stood beside Esther, his jaw clenched so tight his teeth hurt.

His hands were baldled into fists at his sides.

“She deserved better,” he whispered, his voice rough with emotion he couldn’t express more openly.

“She deserved so much better than this.” Esther nodded, wiping her eyes.

They all deserve better, child.

Every single person who dies in this place deserves better.

But this is the world we live in.

This is what they think we’re worth.

Less than animals, less than dirt.

They stood there until full dark, watching the unmarked grave, saying their own quiet prayers, mourning a child they had known for 9 years who had never been allowed to truly live.

Then they went back to their cabin because the work bell would ring again at 5:00 a.m.

and they had to be ready.

Life at Blackwood Plantation continued.

The cotton didn’t stop growing because a child died.

The work didn’t pause for grief.

Everything just moved forward like Sarah had never existed.

The next day, August 16th, life returned to normal.

People went to the fields.

Cotton was picked.

quotas were enforced.

Margaret noted Sarah’s death in her ledger with a simple entry.

Sarah Sutton, age nine, died August 15th, 1856.

Loss of asset value 250.

She would claim it as a business loss on her taxes, perhaps reducing her burden by a few dollars.

The grave behind the barn was unmarked and already starting to sink slightly as the dirt settled and compressed.

August 17th passed the same way.

Work, heat, exhaustion, sleep, repeat.

Nobody talked about Sarah.

Talking about the dead was considered bad luck.

And besides, what was there to say? Another child had died.

It happened all the time.

You mourned if you could.

You moved on because you had to, and you hoped you wouldn’t be next.

But on August 18th, 3 days after Sarah’s burial, something happened that would change everything at Blackwood Plantation.

The night of August 18th was hot and still, the air heavy with moisture that promised rain, but never delivered.

There was no breeze, no relief from the oppressive heat even after the sun went down.

Most people at Blackwood were asleep by 900 p.m., exhausted from another brutal day of labor.

The few who were still awake, sitting outside their cabins, trying to find some cooler air, heard it first.

A sound that didn’t belong.

A scraping sound, like something digging or clawing, coming from the direction of the barn.

At first, they thought it was an animal, maybe a dog or raccoon getting into something.

But then the sound got louder, more deliberate, more purposeful.

And the dogs, all six of them that lived around the plantation, started barking, all of them, all at once, in a way that made your skin crawl in a way that spoke of primal fear rather than territorial aggression.

This wasn’t their normal barking at an intruder or another animal.

This was different.

This was the sound dogs make when they sense something fundamentally wrong, something that violates the natural order.

They barked and howled, backing away from the barn, hackles raised, some of them trembling.

One of the dogs urinated in fear, which dogs don’t do unless they’re absolutely terrified.

James, one of the house servants, valued at $700, who often had night duties, grabbed a lantern and went to investigate.

He called to the dogs to be quiet, but they wouldn’t stop, wouldn’t even come near him.

They just stood at a distance, continuing their fear crazed barking, looking towards something behind the barn that James couldn’t see yet.

He walked slowly around the building, holding the lantern high, his heart beating faster with each step, though he couldn’t say why.

The air felt wrong somehow, colder than it should be, heavy with something he couldn’t name.

He saw the graves first, three small mounds where people had been buried over the past two months.

The dirt on two of them was undisturbed, settled and smooth.

But the third one, the newest one, Sar’s grave, was different.

The dirt had been disturbed, more than disturbed.

There was a hole, a hole coming up from below, like something had dug its way out from the inside.

And as James got closer, his heart pounding so hard he could hear it in his ears.

He saw something that made him drop the lantern that made him scream louder than he had ever screamed in his life.

A small hand pale in the moonlight sticking up out of the dirt.

Fingers moving, grasping, pulling, and beneath the hand, a face covered in dirt, eyes open, mouth gasping for air.

Sarah Sutton was climbing out of her grave.

James’ scream cut through the night like a knife, waking half the plantation.

People came running from all directions from the slave quarters and the main house, carrying lanterns and torches, asking, “What was wrong? What happened? Why was James screaming like someone was being murdered?” He couldn’t answer.

He just stood there pointing at the grave with a shaking hand.

His mouth moving, but no words coming out.

His eyes wide with terror and disbelief.

Coleman Briggs arrived first from the overseer’s house, pulling on his pants, carrying his rifle, ready for trouble.

He pushed through the gathering crowd, cursing everyone for the disturbance, demanding to know what fool woke him up in the middle of the night.

Then he saw what James was pointing at, and stopped dead in his tracks.

His rifle lowered slowly.

His face went pale in the torch light.

Behind him, more people gathered, enslaved workers and white staff members, all carrying lights, all pushing forward to see what caused such commotion.

The crowd grew to 20, then 30, then 40 people, all standing in a semicircle around the grave site, all staring at something impossible, something that violated every natural law they understood about life and death.

Sarah Sutton was pulling herself up and out of her grave.

Her movements were slow but deliberate, purposeful.

Both hands now gripped the edge of the hole, her thin arms straining as she hauled herself upward.

Dirt fell off her in clumps, cascading down the burial canvas that still partially wrapped her small body.

Her hair was matted with soil, thick and dark and wet looking in the moonlight.

Her dress, the simple slave clothing she had died in, was torn and filthy, stained with 3 days of burial.

But her eyes were what made everyone take an involuntary step backward.

Her eyes were open, clear, and focused in a way they never had been during her life.

They seemed to glow slightly in the torch light, reflecting the flames in a way that human eyes shouldn’t.

She looked around at all the shocked faces staring at her, making eye contact with person after person, and in each gaze was something that made grown men and women feel like children caught doing something terrible.

She pulled herself completely out of the hole and stood on shaky legs beside her own grave.

She was so small, so thin, covered in dirt from head to toe, looking more like a ghost or spirit than a living child.

For a long moment, nobody moved.

Nobody spoke.

The only sounds were the dogs continuing their terrified barking from a safe distance and the crackling of torches in the still night air.

It was impossible.

Everyone knew it was impossible.

Sarah Sutton had been dead.

Dr.

Merritt had pronounced her dead 3 days ago.

He had checked her pulse multiple times, held a mirror to her mouth, listened to her chest.

She had no heartbeat, no breath, no signs of life whatsoever.

They had buried her 4 feet underground wrapped in canvas.

No air could get into that grave.

No water, no food.

A person could not survive being buried for 3 days.

It was medically, physically, scientifically impossible.

Yet here she stood, breathing, moving, alive.

Esther was the first to break from the crowd.

She pushed through the stunned onlookers and ran to Sara, falling to her knees in front of the girl.

Her hands reached out but hesitated, afraid to touch, afraid this was a ghost or hallucination, afraid that touching would make it disappear.

Child Sarah, is that really you? Are you really alive? Her voice was shaking, tears already streaming down her weathered face.

Sarah looked down at Esther and nodded slowly.

When she spoke, her voice was different from before.

It was still quiet, but it carried strength now, certainty, a quality it had never possessed during her short life.

Her vocal cords were raw and damaged from 3 days without water, making her voice rough and scratchy.

But somehow that made it more commanding, more serious.

Yes, Esther, it’s me.

I’m alive.

I came back.

The words hung in the air like smoke.

I came back.

Not I woke up or I survived.

I came back as if death had been a place she visited and then left.

As if she had made a choice to return rather than simply never having been fully dead.

The distinction was subtle, but everyone felt it.

that sense that this was something more than a medical mistake or miraculous recovery.

Dr.

Merritt was called immediately.

Someone ran to wake him, pounding on his door until he stumbled out in his night shirt, grumbling about being disturbed about how plantation owners never let doctors sleep properly.

He was 72 years old, and sleep didn’t come easy anymore.

He needed his rest.

But when the servant grabbed his arm and dragged him toward the barn, stammering about Sarah Sutton being alive, Dr.

Merritt went from annoyed to terrified in seconds.

He arrived at the grave site, breathing hard from the exertion, his old heart pounding when he saw Sarah standing there covered in dirt, but clearly alive and conscious.

His face went white as chalk, his legs almost gave out.

Someone had to catch his arm to steady him.

He had pronounced her dead.

He had signed the certificate.

He had been absolutely, completely, professionally certain.

But there she was, standing and breathing and looking at him with those strange knowing eyes.

Dr.

Merritt rushed forward, his medical training overriding his fear.

He grabbed Sarah’s wrist, pressing his fingers against the pulse point.

It was there, strong and steady, beating at about 70 beats per minute, perfectly normal for a child her age.

He pressed his ear against her chest, listening.

Her heart was beating regularly.

No irregularities, no signs of the failure he had diagnosed 3 days ago.

He pulled back her eyelids to examine her pupils.

They were normal, reactive to the torch light.

no sign of the rolled back death state he had observed.

He checked her temperature by pressing his hand against her forehead and neck.

She was warm, normal body temperature, not the cold stillness of death or the burning fever that had consumed her before.

He checked her hands and feet.

Blood flow was good.

Color was returning.

Fingers and toes moved normally when he asked her to wiggle them.

He listened to her lungs.

They were clear.

No fluid, no rattling, no sign of the pneumonia that had been killing her 72 hours ago.

“This is impossible,” Dr.

Merritt whispered, more to himself than to anyone else.

“You were dead,” I checked three times, four times even.

“You had no pulse, no heartbeat, no breath.

Your body was cold.

Your eyes were fixed and dilated.

You were dead by every medical standard I know.” He was shaking now, his professional certainty shattered.

his entire understanding of medicine and biology called into question by this small dirtcovered child.

Sarah looked at him with those clear, focused eyes that seemed far too old for her face.

I was dead, Dr.

Merritt.

You weren’t wrong.

Your examination was correct.

My heart stopped beating at 8:35 p.m.

on August 15th.

My breathing stopped.

My brain stopped receiving oxygen.

I died.

She spoke with certainty, with knowledge that a 9-year-old girl shouldn’t possess.

But death isn’t always final.

Sometimes death can be reversed.

Sometimes what’s gone can come back.

Margaret Sutton arrived then, wrapped in a robe despite the heat, her gray hair loose around her shoulders, her face showing fury at being woken in the middle of the night.

She had been sleeping poorly lately, troubled by dreams she couldn’t quite remember upon waking, and this disturbance had pulled her from the first deep sleep she’d had in days.

She pushed through the crowd of enslaved people and staff, demanding to know what was happening.

What emergency required waking the entire plantation at this ungodly hour? When she saw Sarah alive and standing by her grave, Margaret stopped mid-sentence.

Her mouth hung open.

Her eyes went wide.

For several long seconds, she couldn’t process what she was seeing.

Her brain refused to accept it.

Kept insisting this must be someone else, some other girl.

Because Sarah Sutton was dead and buried 3 days ago.

But she recognized the face, even covered in dirt.

She recognized the small, thin frame.

She recognized the torn dress that had been Sarah’s only clothing.

Margaret’s expression went from confusion to something that might have been fear, though she would never have admitted it.

She was a practical woman who believed in facts and figures, in things that could be measured and calculated.

Death was final.

Dead people stayed dead.

That was a fundamental rule of existence.

Yet here was evidence that challenged that rule that suggested reality was more complicated and terrifying than her neat ledgers and calculations allowed for.

“Explain this,” Margaret demanded, her voice sharp, but with a tremor underneath that betrayed her composure.

“Someone explain this right now.

Doctor Merritt, what happened? How is this possible?” She looked around at the crowd, at the faces showing shock and fear and something else, something that looked like hope or vindication, expressions she didn’t like seeing on enslaved faces.

Dr.

Merritt stammered, trying to form words, trying to construct an explanation that made sense within his understanding of medicine.

She must have been.

It could have been catalpsy.

A rare condition where the body enters a death-like state, but isn’t actually dead.

The vital signs become so weak they’re nearly undetectable.

Breathing slows to perhaps one breath per minute.

Heartbeat to maybe five or six beats per minute.

It mimics death perfectly.

I must have missed it.

I must have made a mistake in my diagnosis.

He was grasping at straws and everyone knew it.

Catalpsy didn’t explain how someone could survive 3 days buried underground with no air.

Even if Sara had been in a catalic state when buried, she would have suffocated within minutes once the dirt was piled on top of her.

The canvas wrapping would have blocked any tiny amount of air that might have filtered through the soil.

There was no medical explanation for this.

None at all.

Briggs stepped forward, his rifle gripped tight in his hands.

He had recovered from his initial shock, and was now angry, as he always was when confronted with something he didn’t understand.

Anger was easier than fear.

Anger was something he knew how to handle.

Maybe she wasn’t all the way dead.

Maybe she was just mostly dead and woke up in the ground and dug herself out.

But even as he said it, he didn’t believe it.

He had helped bury her.

He knew how deep the grave was, how much dirt they had piled on top.

A grown man would struggle to dig out from that depth.

A small, sick 9-year-old girl.

Impossible.

Sarah looked at Coleman Briggs and he actually took a step backward despite himself.

Despite his size and strength and the rifle in his hands, there was something in her gaze that stripped away his bravado, that made him feel exposed and vulnerable.

I didn’t dig out Mr.

Briggs.

The earth released me.

It didn’t want me.

Death sent me back.

Her voice was quiet, but it carried.

Everyone in the crowd heard her clearly.

I was in darkness for a long time.

Cold and alone.

I couldn’t breathe, but I didn’t need to.

I couldn’t move, but I didn’t hurt.

I just existed in nothing for what felt like forever.

She turned slowly, looking at all the faces gathered around her.

Then something spoke to me.

I don’t know what it was.

A voice without sound.

It said I could stay there in the dark or I could go back.

But if I went back, I would have to finish something.

I would have to make things right.

I would have to show them.

She looked directly at Margaret now.

Show them what they did.

Show them what we’re worth.

Show them that you can’t just throw people away like garbage and expect no consequences.

The crowd of enslaved people started murmuring, whispers spreading like ripples in water.

Some made signs against evil, old gestures their grandparents had brought from Africa, symbols meant to ward off spirits and unnatural things.

Some whispered prayers calling on Jesus or older gods seeking protection from whatever this was.

But others looked at Sarah with something different in their eyes.

Something like recognition, like she represented something they had been waiting for without knowing it.

Because they all understood what they were seeing, even if they couldn’t explain it.

This wasn’t a medical mistake.

This wasn’t someone waking up from a coma.

This was something that shouldn’t be possible, but was happening anyway.

This was the natural order breaking, bending, allowing something through that normally stayed on the other side.

This was resurrection or visitation or possession or something else they had no name for.

Whatever it was, it was real and it was standing in front of them covered in grave dirt.

Margaret tried to take control of the situation, tried to impose her authority and restore the order that made her world function.

This is nonsense.

Superstitious nonsense.

The girl was in a coma or catalyptic state.

Dr.

Merritt made an understandable error in diagnosis.

Sarah, you were very sick and confused.

You woke up disoriented and managed to dig yourself out somehow.

That’s all.

This is a medical mistake and a fortunate survival.

Her voice was firm, commanding, but her hands were shaking.

Everyone go back to bed.

Sarah will be examined properly in the morning.

This incident is over.

But nobody moved.

They all just stood there staring at Sarah, waiting to see what she would do next, what she would say.

The power dynamic had shifted somehow in ways Margaret could feel but not quite understand.

Her words, which normally would have scattered the crowd immediately, had no effect.

For the first time in her life, Margaret Sutton stood in front of enslaved people and felt powerless.

Sarah looked at Margaret for a long moment, and when she spoke, her voice was calm, but carried absolute certainty.

“You’re lying, Mrs.

Sutton.” To them and to yourself, “You know I was dead.

Dr.

Merritt knows.

Mr.

Briggs knows.

Everyone here knows.

I had no heartbeat, no breathing.

I was cold and stiff.

I was dead for 3 days.” She took a step toward Margaret and Margaret actually stepped backward.

something she would never normally do in front of enslaved people.

3 days ago, you decided I wasn’t worth saving.

You did the math.

$5 for medicine versus $250 of value.

You calculated that saving me wasn’t a good investment.

The crowd was completely silent now.

Everyone listening, everyone watching this small child confront the most powerful person on the plantation without fear, without deference, without the submission that had been beaten into them since birth.

Sara continued, her voice growing stronger.

You put a price on my life and decided it wasn’t high enough.

You let me die to save $5.

You buried me behind the barn like a dead animal because you thought I was worthless.

Margaret’s face flushed red with anger and embarrassment.

That’s not how it was.

That’s not Medical decisions are complicated.

The treatment wouldn’t have worked.

You were too far gone.

I made a practical decision based on expert advice.

But her voice was defensive, lacking its usual authority because Sarah was right.

That was exactly how it had been.

Margaret had done the calculation and decided Sarah wasn’t worth the cost.

Sarah smiled and it was not a child’s smile.

It was knowing ancient carrying weight that no 9-year-old should possess.

I know what I’m worth now, Mrs.

Sutton.

I’m worth more than your whole plantation.

I’m worth more than everything you own because I came back from death.

I walked in darkness and returned to light.

I crossed a threshold that no one crosses and then crossed it again going the other direction.

I am proof that your calculations are meaningless, that your ledgers don’t capture what matters, that you don’t control everything you think you control.

She spread her arms wide, gesturing at the crowd around her.

We are all worth more than the prices you put on us.

Every single person here.

We’re not inventory.

We’re not assets.

We’re human beings with souls and dignity.

And I came back to prove it.

I came back to show everyone what you really are, what you did, what you do every single day to all of us.

Margaret tried to speak, but no words came out.

She opened her mouth and closed it again, her face cycling through expressions of rage, fear, and confusion.

She looked around at the crowd, at her overseer, at her doctor, seeking support, seeking someone to back her up, to restore order.

But Briggs was staring at Sarah with barely concealed fear.

Dr.

Merritt was shaking, pale as death, unable to reconcile what he was seeing with everything he thought he knew about medicine.

And the enslaved people were looking at Sarah with expressions that terrified Margaret more than anything else.

They were looking at her with hope, with belief, with the kind of dangerous faith that could lead to rebellion, to uprising, to the complete collapse of the system that kept them controlled.

Hope was the most dangerous thing slaves could have.

Hope made them stop accepting their condition.

Hope made them start imagining alternatives.

Hope made them willing to risk everything for the chance at something better.

Briggs finally found his voice, tried to reassert control in the only way he knew how, through threats and violence.

He raised his rifle, pointing it at Sara, his finger on the trigger.

That’s enough.

You don’t talk to Mrs.

Sutton that way.

You’re still property.

You’re still a slave.

You don’t get to make speeches and accusations.

This is over right now.

You’re going to He stopped because Sarah was looking at him.

really looking at him.

And her eyes had changed.

They were darker now, deeper, like looking into wells with no bottom, like looking into the void between stars.

Her pupils seemed to expand until they swallowed the whites of her eyes, until there was nothing but darkness looking out from her small face.

You hit me many times, Mr.

Briggs.

You called me worthless.

You said I should die.

You said I was stealing food by being alive.

You were right about the dying part.

Her voice had changed, too, deeper with harmonics that didn’t seem to come from human vocal cords.

But you were wrong about everything else.

Briggs pulled the trigger.

The shot rang out loud in the night, the muzzle flash bright as lightning, the sound echoing off the barn and the main house.

Everyone screamed or ducked or dove for cover.

The shot was point blank, maybe 10 ft, and Briggs was known as an excellent marksman who could shoot a rabbit at 50 yards.

But the bullet didn’t hit Sarah.

It struck the ground 3 ft to her left, kicking up a small spray of dirt.

Briggs stared at his rifle in confusion, in disbelief.

How had he missed? How was that possible? He raised the rifle again, aimed more carefully this time, his hands shaking, but his aim steady.

He fired again.

This shot went high, whistling over Sarah’s head by at least two feet.

He fired a third time, a fourth time, emptying the rifle.

Every shot missed.

Every single one, despite perfect aim, despite a stationary target, despite years of shooting experience, the bullets went everywhere except where they were aimed like some invisible force was deflecting them, bending their trajectories at the last moment.

Sarah walked toward Briggs slowly.

He backed away, his hands shaking so badly now he dropped the empty rifle.

His face showed pure terror.

All the bravado and cruelty stripped away, leaving just a frightened man confronting something he couldn’t understand or control.

Stay away from me.

Stay away.

He turned and ran toward his house, stumbling over his own feet, not looking back, running like a child, fleeing a nightmare.

Sarah didn’t chase him.

She just watched him go, her expression calm, almost sad.

Then she looked at the crowd of enslaved people, and her expression softened.

When she spoke again, her voice was back to normal, or as normal as it could be given the circumstances.

I’m not here to hurt you, any of you.

I’m not a monster or a demon or anything evil.

I’m just Sarah.

But something happened to me in those three days.

Something changed me, showed me things, gave me purpose.

She looked at Margaret again.

I’m here for the ones who hurt us.

The ones who decided our lives don’t matter.

The ones who treat us like animals or property or numbers in a ledger.

It starts with them.

She pointed at Margaret.

It starts with the people who make the calculations, who decide who lives and who dies based on profit and loss, who create a system where a child’s life is worth less than $5 of medicine.

Margaret finally found her voice, though it came out shaky and weak.

You’re insane.

You’re a child having delusions from trauma and oxygen deprivation.

Someone grab her and lock her in the barn until morning.

We’ll deal with this when everyone can think clearly.

But nobody moved to grab Sarah.

Nobody wanted to touch her.

Even the white staff members, who normally would have jumped to obey Margaret’s orders, stood frozen, unwilling to approach this small girl who had clawed her way out of a grave.

Sarah looked around at all of them one more time, her gaze lingering on Esther, on Daniel, on the other enslaved people who had known her, who had watched her suffer, who had mourned her death.

I came back to make things right, to show everyone the truth.

It won’t be quick, and it won’t be easy, but it will happen.

Justice is coming to Blackwood Plantation.

The kind of justice that doesn’t care about property laws or economics.

the kind that balances the scales no matter what it costs.

Then she turned and walked slowly toward the slave quarters, toward the cabin she had shared with Esther.

The crowd parted to let her through, people stepping aside quickly, not wanting to block her path.

Some reached out as if to touch her, but pulled their hands back at the last moment, afraid or reverent, or both.

Sarah walked with her head up, her back straight, moving with a confidence and dignity she had never shown in life.

She looked like someone who had nothing left to fear because she had already experienced the worst thing possible and survived it.

She went into the cabin and lay down on her sleeping mat, the same mat where she had slept for 9 years, where she had died in spirit long before her body gave out.

Esther followed her inside, not knowing what else to do, needing to be near this child she had tried to protect and failed to save.

Sarah closed her eyes and within minutes appeared to be sleeping, her breathing deep and regular, her face peaceful in a way it never had been before.

Esther sat beside her, staring at the girl who had died and somehow come back.

She reached out carefully and touched Sarah’s face, half expecting her hand to pass through like Sara was a ghost or spirit.

But the skin was solid and warm, real flesh and blood, unmistakably alive.

Yet when Esther pulled her hand back, there was dirt on her fingers.

Dirt from the grave, soil that had covered Sarah’s body for 3 days, earth that should have been her final resting place.

And Esther knew deep in her heart, in the part of her that remembered older beliefs her grandmother had taught her before Christianity tried to replace them, that Sarah had told the truth.

She had died.

She had been somewhere else, somewhere beyond life.

And she had come back for a reason.

The dead didn’t return without purpose.

They came back when there were debts unpaid, when justice had been denied, when the scales needed balancing.

Outside, the crowd slowly dispersed.

People returning to their cabins, but knowing sleep would be impossible.

They would lie in their beds and stare at the ceiling and replay what they had witnessed, trying to make sense of it, trying to fit it into their understanding of how the world worked.

Some would pray, some would cry.

Some would feel hope for the first time in years.

Hope that maybe their suffering wouldn’t last forever.

That maybe there were forces in the universe that cared about justice even when humans didn’t.

Margaret stood in front of her house watching the quarters.

Her mind racing.

This had to be explained, had to be rationalized, had to be controlled before it spread beyond the plantation.

People didn’t come back from the dead.

That was superstition, ignorance, primitive beliefs.

There had to be a logical explanation, catalpsy, premature burial, somehow digging out something scientific that made sense within the natural laws, she understood.

But in her heart, in the part of her that still believed in things beyond money and property and profit, in the part she tried to ignore because it interfered with business, Margaret knew something terrible had happened.

Something had shifted at Blackwood Plantation on this hot August night.

The natural order had been violated.

The dead had returned and whatever came next, whatever consequences followed from that impossible resurrection would not be in her control.

Dr.

Merritt sat in his room, staring at the death certificate he had signed 3 days ago.

The paper seemed to mock him, every word proof of his failure, evidence that his certainty had been misplaced, that his professional judgment was worthless.

Sarah Sutton, age 9, died at 8:35 p.m.

on August 15th, 1856.

Cause pneumonia and systemic failure.

He had signed it, dated it, recorded it in his ledger with absolute confidence.

But Sarah Sutton was not dead.

She was sleeping in the quarters right now, breathing and alive.

He had been wrong or something impossible had happened.

Either way, his hands wouldn’t stop shaking.

Either way, his entire understanding of medicine and death and the boundary between them had been shattered.

He pulled out a bottle of whiskey, something he rarely indulged in, and poured himself a large glass.

He needed to dull the fear, needed to stop thinking about what he had seen, needed to forget the look in Sarah’s eyes when she said, “I was dead.” Coleman Briggs barricaded himself in his room, pushing furniture against the door, loading every gun he owned.

He had six rifles now ready and two pistols all loaded and primed.

He kept the lamps burning, terrified of the dark, terrified of what might be hiding in shadows.

Every sound made him jump.

Every creek of the floorboard sounded like footsteps.

Every movement of curtains in the breeze looked like a small figure standing in the corner.

He told himself he wasn’t afraid of a child.

He had broken grown men, had beaten people who begged for mercy, and laughed while doing it.

He was strong, powerful, feared by everyone on the plantation.

But that thing he had seen, those eyes looking at him, that voice promising consequences, that wasn’t a child.

that was something else wearing a child’s face and it knew his sins.

It knew every time he had hit her, every insult he had spoken, every moment of cruelty.

It remembered all of it, and it had come back to collect payment.

As dawn approached on August 19th, Blackwood Plantation sat in an uneasy quiet that felt more threatening than any loud disturbance.

The sun would rise soon, painting the sky in reds and oranges.

People would have to go to the fields.

Work would have to continue.

Cotton needed picking regardless of what impossible things happened in the night.

Margaret would try to restore order, to make everyone forget what they had seen, to explain it away as medical error and mass hysteria and nothing more.

But they all knew the truth.

Something had come back from death.

Something that remembered every cruelty, every injustice, every calculation that valued profit over human life.

Something that promised consequences, that spoke of justice and balance and debts that needed paying.

And whether it was Sarah Sutton returned from the grave or something else using her body, the result was the same.

Blackwood Plantation would never be the same again.

The morning of August 19th dawned gray and heavy.

The sky covered in clouds that threatened rain but delivered none.

That just hung there oppressive and dark, like a ceiling pressing down.

The air felt thick, hard to breathe, charged with something electrical and wrong.

The plantation felt different, looked different, though nothing physical had changed.

It was the atmosphere, the feeling, like the land itself knew something terrible had happened and was waiting to see what came next.

The bell rang at 5:00 a.m.

as always, calling people to the fields.

But this morning, many were reluctant to leave their cabins.

They gathered in small groups, whispering, glancing toward the cabin where Sara slept, afraid to go near, but unable to look away.

The bravest among them approached Esther’s cabin and peered through the gaps in the walls, trying to see if Sara was still there, if she was real, if last night had actually happened, or was some shared fever dream brought on by heat and exhaustion and desperation.

Sarah was there, sleeping peacefully, her chest rising and falling with regular breaths.

She looked normal in the morning light, just a small girl who needed to wash the dirt from her hair and skin.

But everyone who looked at her felt it.

That sense of wrongness, that awareness that this was not the same Sara who had died 3 days ago.

Something fundamental had changed.

Something essential was different.

Margaret Sutton had not slept at all.

She sat at her desk in the main house, still in her nightclo, staring at her ledgers, but not really seeing the numbers.

Her mind kept replaying the impossible sight of that child climbing out of her grave, walking and talking after being dead for 3 days.

Margaret was a practical woman who believed in facts and figures, in things that could be measured and calculated and controlled.

Death was final.

Dead people stayed dead.

That was a fundamental rule of existence, possibly the most fundamental rule.

Yet what she had witnessed had violated that rule so completely, so undeniably that it shook the foundation of everything she believed.

If death wasn’t final, if the dead could return, if the natural laws she depended on could be broken so easily, then what else was she wrong about? What other certainties were illusions? what other rules might bend or break when pressed.

At 6:00 a.m., she called for Dr.

Merritt and Coleman Briggs to meet her in the study.

She needed to discuss this situation, needed to form a plan, needed to reassert control before things spiraled further.

Dr.

Merritt arrived looking terrible, his eyes red and bloodshot, his hands trembling as he poured himself coffee from the service Margaret’s house slaves had prepared.

He had aged 10 years overnight.

His face drawn and haggarded, his confidence shattered.

Briggs was worse.

He arrived 15 minutes late, which was unprecedented, carrying two loaded pistols openly on his belt and a rifle over his shoulder.

His eyes were wild, darting around constantly, seeing threats in every shadow.

He had dark circles under his eyes from lack of sleep.

His usual swagger was gone, replaced by nervous energy and barely controlled fear.

He sat across from Margaret’s desk, but wouldn’t put down his weapons, keeping them close, ready, they sat in uncomfortable silence for a moment.

Then Margaret spoke, her voice firm, but with a tremor underneath that betrayed her composure.

We need to control this situation before it gets worse.

Before word spreads beyond the plantation, before we have a full panic, or worse, a rebellion.

She looked at both men, demanding their attention, demanding they focus.

The official story is that Sarah was in a catalic state.

Dr.

Merritt made an understandable diagnostic error.

She recovered and dug herself out.

That’s what we tell everyone.

That’s what goes in all official records.

Dr.

Merritt nodded eagerly, grateful for any explanation that didn’t require him to admit he had witnessed something impossible.

Yes, of course.

Catalpsy.

It’s rare, but documented in medical literature.

The body enters a death-like state.

Vital signs become nearly undetectable.

I should have recognized it.

Should have been more thorough in my examination.

My mistake entirely.

He was lying to himself and knew it.

But lies were easier than truth when truth meant abandoning everything you thought you understood about the world.

Briggs leaned forward, his jaw tight.

What about what she said about coming back from death about making things right? She threatened you directly, Mom.

That can’t be allowed.

She needs to be punished severely.

needs to be sold south immediately before she causes real trouble before she infects the others with her crazy talk.

His voice carried desperation, the need to remove the source of his fear to make the threat go away.

Margaret considered this selling Sarah would remove the immediate problem from Blackwood, but it would also spread the story.

Every plantation Sarah went to, every slave trader who handled her, every enslaved person who heard about her would hear the tale of the girl who died and came back.

The story would spread like wildfire through slave communities across the South, passed along the invisible networks of communication that moved information faster than any telegraph.

That kind of story was dangerous.

It would inspire hope.

And hope was the most dangerous thing enslaved people could possess.

Hope made them stop accepting their condition.

Hope made them believe in alternatives in possibilities beyond their current suffering.

Hope could lead to resistance, to escapes, to rebellions that would cost Margaret everything.

The Nat Turner rebellion 25 years ago had started with a man who believed God had chosen him for a special purpose.

What might happen if enslaved people across the South started believing a 9-year-old girl had been resurrected to bring justice to their oppressors? No.

Margaret decided firmly.

She stays here where we can control her, where we can control the story and make sure it doesn’t spread beyond the plantation boundaries.

If she’s sold, the tale grows with every telling, becomes bigger and more dramatic.

Here, we can manage it.

We can make sure people understand it was a medical error.

Nothing supernatural, nothing that should inspire hope or resistance.

She looked at both men with determination.

Sarah is sick, confused, traumatized from her experience of being buried alive.

She’s saying things that don’t make sense because her mind was damaged by oxygen deprivation.

We treat her with patience and kindness.

Show everyone that we’re reasonable and compassionate.

We prove that her accusations are the ravings of a confused child.

That’s how we handle this.

But even as Margaret spoke these words with confidence, even as the three of them nodded in agreement about the official story, they all knew they were lying to themselves.

They had all seen Sarah’s eyes, had heard the certainty in her voice, had felt the wrongness of her presence.

This wasn’t a confused child.

This wasn’t medical error or oxygen deprivation.

This was something else entirely, something that didn’t fit into their comfortable explanations and rational worldview.

At 7:00 a.m., Margaret sent for Sara.

Esther brought the girl to the main house, walking slowly.

Sara’s small hand in her weathered one.

The child had been washed, the grave dirt removed from her hair and skin, dressed in clean clothes.

In the morning light, walking into the plantation house, she looked almost normal, just a thin 9-year-old girl, small for her age, nothing special or frightening about her.

But when she entered Margaret’s study, when she stood across the desk from the woman who owned her, who had decided she wasn’t worth saving, the atmosphere in the room changed.

The temperature seemed to drop.

The air felt heavier.

The sunlight coming through the windows seemed dimmer, filtered through something invisible, but present.

Margaret felt it.

Briggs felt it.

Dr.

Merritt felt it.

that sense of being in the presence of something that shouldn’t exist.

Margaret studied Sarah carefully, looking for some sign of the terrifying figure from last night, looking for evidence of disease or damage that would support her explanation of trauma and confusion.

But Sarah looked back at her with calm, clear eyes, old eyes in a young face, eyes that had seen things Margaret couldn’t imagine, eyes that judged and found her wanting.

Sarah, Margaret began using her gentlest voice, the tone she reserved for important guests or difficult negotiations.

You gave us all quite a scare last night.

Dr.

Merritt tells me you were very sick.

You fell into a kind of deep sleep called catalpsy that made you seem dead.

It’s very rare, but it happens.

Your mind and body shut down to preserve life.

That’s why we thought you had died.

That’s why we buried you.

It was a mistake.

A terrible mistake, but an understandable one.

Margaret leaned forward, trying to seem concerned and caring rather than calculating.

Now, I know you said some things last night that were inappropriate, about dying and coming back, about making things right, about justice.

I understand you were confused and frightened.

You had just woken up buried alive, which would terrify anyone, especially a child.

Your mind was scrambling to make sense of a traumatic experience, so it created this narrative about death and resurrection.

She smiled, trying to look warm and motherly, an expression that sat awkwardly on her usually stern face.

But that’s not what really happened.

You were never actually dead.

You were sick, very sick, and you fell into this special kind of sleep.

Doctor Merritt made an error which he deeply regrets.

We buried you by mistake.

You woke up, managed to dig yourself out somehow, and now you’re recovering.

That’s the truth.

That’s what actually happened.

Do you understand? Sarah looked at Margaret without blinking, her gaze steady and unwavering.

When she spoke, her voice was quiet, but carried perfect clarity.

You’re lying to me, to yourself, to everyone.