💀🌿 The $12 Slave Who Became a Force of Revenge and Mercy—How Celia Turned a Plantation into Her Own Deadly Classroom

August 17th, 1859, marked a pivotal moment in the history of Savannah’s largest slave auction house.

As the sun blazed down on the sweltering afternoon, the atmosphere inside the auction house was thick with tension.

Lot number 43 stepped onto the platform, and an eerie silence fell over the room.

Twenty-seven bidders had their paddles ready, but as the auctioneer called for bids, only one hand remained raised.

The woman standing there, young and healthy, bore chains that clinked softly as she shifted her weight.

Her starting price was deliberately set low, but something in her presence made the seasoned plantation owners lower their eyes and step back.

They knew something—something whispered about in the shadows of the corridors, but never spoken aloud.

A man newly arrived from Charleston didn’t hear those whispers.

He paid $12 for a woman worth 200, and within six months, he would understand why silence had filled that auction house, and by then, it would be far too late to save himself.

The auction house on Broton Street had seen thousands of transactions since its establishment in 1842, but the events of that August afternoon would be remembered differently than any other sale.

The air inside the building was thick with the stench of unwashed bodies, tobacco smoke, and the palpable fear that no amount of whitewash could cover.

But there was something else that day—something that made even hardened slave traders shift uncomfortably in their seats.

Savannah in 1859 stood as one of the South’s most prosperous cities, its wealth built entirely on cotton and forced labor.

The city’s port handled millions of pounds of the white crop each year, and the plantations surrounding it competed viciously for the most productive workers.

Chatham County’s soil was rich, its growing season long, and its plantation owners ruthless in their pursuit of profit.

Thomas Cornelius Puit arrived in Savannah three weeks before that fateful auction.

At 34 years old, he represented new southern money, the kind that made old families uncomfortable.

His father had made a fortune in Charleston through cotton speculation, dying suddenly and leaving Thomas with more wealth than experience.

Thomas had purchased the old Waverly plantation site unseen, eager to prove himself among Georgia’s planting elite.

The property came cheap, the previous owner having died without heirs, and Thomas saw it as his opportunity to build a legacy.

The Waverly estate stretched across 800 acres of prime cotton land along the Vernon River, the main house displaying columned grandeur despite needing repairs.

Forty-two enslaved people came with the property, but Thomas’s overseer, a lean man named Hutchkins, advised he would need at least 60 to work the land properly for the coming season.

Hence, his presence at the Broton Street auction house that August morning, cash in hand and determination in his eyes.

The auction began at 10:00 AM.

Thomas bid successfully on three young men and an experienced cook, spending nearly $5,000 by noon.

During the lunch break, he overheard a conversation between two planters he recognized from a dinner party the previous week.

“You staying for the afternoon session?” one asked.

“No reason to. Already got what I came for. Besides, I know what’s coming. Heard they’re finally selling her. About time. Been sitting in the holding pens for three weeks. Nobody wants to buy. Still can’t believe what happened at the Peton place. Three men dead inside of two months. Four if you count old Peton himself. Though Dr. Reeves said that was his heart. Mighty convenient timing.”

Thomas stepped back before they could notice him, curiosity piqued when the auction resumed at 1:00 PM.

Several morning bidders had not returned.

The first three afternoon lots sold quickly.

Then came lot 43.

The woman who stepped onto the platform moved with a dignity that seemed impossible given her circumstances.

She appeared to be in her early thirties, her skin the color of polished walnut, features sharp and defined.

But it was her eyes that struck Thomas most—dark, almost black, possessing a quality of stillness that belonged to someone who had stopped hoping and found a different kind of strength in that hopelessness.

“Lot 43,” the auctioneer announced without enthusiasm.

“Female, approximately 32 years of age, name of Celia, experienced in household duties, particularly cooking and medical assistance, has served as midwife and herb doctor, literate in English. No known physical defects. Starting bid of $10.”

Thomas waited for raised paddles.

Instead, silence.

$10 was insultingly low for a woman with medical skills.

Midwives were valuable, often earning owners significant income by attending births throughout the county.

“$10,” the auctioneer repeated.

“Do I hear $10?”

The silence stretched.

Men deliberately looked away, studying floors, ceilings, their own hands—anything but the woman on the platform.

Thomas raised his paddle. “$10 to the gentleman in the blue coat,” the auctioneer said quickly, relief evident.

“Do I hear 12?”

Nothing.

The room remained frozen.

“Going once at $10, going twice, sold for $10 to the gentleman in blue.”

The gavel cracked like a gunshot.

The woman, Celia, turned her gaze toward Thomas for the first time.

Her expression didn’t change, but something in her eyes shifted—a flicker of recognition or assessment.

Then she was led away.

After the auction, Thomas approached the office to complete his purchases.

When he inquired about Celia’s history, the clerk’s pen paused briefly before continuing.

“Came from the Peton estate. Property was liquidated after Mr. Peton’s death three months ago. And her skills are accurately listed. That’s what the estate inventory stated.”

“Seems unusual that no one else bid.”

The clerk looked up briefly. “Not my place to question what buyers do or don’t do, sir. Your total comes to $6,710.”

The journey to Waverly took just over an hour along the river road.

As they approached, the main house came into view—a two-story structure with six columns across the front portico, white paint fading in places.

Beyond lay the quarters—two long buildings—and further still, the cotton fields stretching toward the treeline in neat rows.

When they arrived, Hutchkins organized the new arrivals.

The men would join field gangs.

The cook would take over the main house kitchen, but when it came to Celia, Hutchkins seemed uncertain.

“Where do you want this one, Mr. Puit?”

Thomas considered. “She has medical training. We’ll use her as midwife. Have her set up in the old overseer’s cabin near the quarters.”

Hutchkins nodded slowly. “Yes, sir, though we already have old patients who tend to such things.”

“Then Celia can assist her. Two pairs of hands are better than one.”

Thomas was about to question Hutchkins’s reluctance when a servant approached, informing him that Josiah Krenshaw had arrived to pay respects to the new owner.

Thomas recognized the name from the conversation outside the auction house.

Krenshaw waited on the front portico, a heavyset man in his late fifties dressed in casual elegance.

After exchanging pleasantries over bourbon, Krenshaw shifted the conversation. “I noticed you made some purchases today. Good selections, though I sense you didn’t hear all the talk about one particular acquisition.”

Thomas met his gaze. “You’re referring to Celia for $10?”

“Did you wonder why no one else bid?”

“The thought crossed my mind.”

Krenshaw set his glass down carefully. “That woman came from the Peton estate. Dr. Harold Peton died three months ago. Healthy until he wasn’t. His nephew inherited and immediately sold everything—couldn’t get away fast enough.”

He paused. “Peton’s death wouldn’t have raised eyebrows by itself. But it was what came before. And what came before? His overseer, a man named Kelly, dead from brain fever after two weeks of raving. Before that, Peton’s driver, Marcus, found dead in the stables with a broken neck. They said he was kicked by a horse. But Marcus knew horses better than anyone. And before that, Peton’s physician, Dr. Simon Vance, dead from apparent influenza complications.”

Thomas absorbed this.

“You’re suggesting these deaths are connected?”

“Four men associated with the Peton household died within two months, and the only common thread was that woman.”

“She prepared medicines, tonics, teas, had access to the main house, the kitchen, the sick rooms.”

Krenshaw leaned forward. “And she had reason.”

“What reason?”

“About six months ago, Celia’s daughter took ill. Pneumonia, they thought. Dr. Vance attended her. The girl died three days later. Celia claimed the doctor was drunk, gave wrong treatment, killed her daughter through negligence. She made loud accusations. Peton had her whipped and confined.”

Krenshaw finished his bourbon. “Two weeks later, Dr. Vance was dead. Then Marcus, then Kelly, then Peton.”

“That could be coincidence.”

“Could be. But that woman has knowledge of herbs and plants that goes deeper than most. She knows what cures and what kills, and she’s got nothing left to lose.”

He stood to leave. “I came as a courtesy, Mr. Puit. What you do with the information is your business. But if I were you, I would sell that woman quickly or put her in the fields where she can’t access anyone’s food or drink.”

That evening, Thomas visited the overseer’s cabin where Celia had been housed.

She sat on the rough bed, hands unbound, posture straight despite the day’s ordeal.

She stood when she saw him, but her eyes met his directly.

“You’re Celia,” Thomas said.

“Yes, master.”

“I’m told you have skills as a midwife and herbalist. Where did you learn?”

“My mother was midwife before me. She learned from her mother. I learned from watching, then doing. And I can read, so I studied books when I could find them.”

Her candor surprised him.

“I’m also told you came from the Peton estate.”

“There were several deaths there.”

“People die, master. That’s the one certain thing in this world.”

“Indeed, but the timing caused some talk.”

Celia said nothing for a long moment.

Then she said, “They didn’t understand something.”

“What didn’t they understand?”

Celia looked at him with a calm intensity.

“That debts come due. One way or another, everything balances in the end.”

The statement could have been philosophical or threatening.

Thomas decided to be direct. “Did you kill them?”

She smiled slightly without warmth. “Can’t kill a man with words, master, or with prayers or with hoping real hard that justice finds them. If they died, it was divine providence or their own sins catching up.”

“I’m just a slave. I don’t have the power to do anything but what I’m told.”

“You’ll work as midwife here, tend to the sick, deliver babies, prepare medicines as needed under old patients’ supervision.”

“Yes, master.”

“And Celia, whatever happened at Peton’s place, it stays there. Here at Waverly, we start fresh.”

“Understood?”

“Yes, master. Understood perfectly.”

That night, Thomas lay in bed thinking about Celia’s daughter, dead at 16 from pneumonia or a doctor’s negligence.

He thought about a mother’s grief and what it might drive someone to do.

He thought about herbs and plants, how the same knowledge that eased pain could cause it.

Most of all, he thought about four dead men and one woman with nothing left to lose.

The harvest began in late September.

Dark clouds had been building over the Atlantic for days.

A late-season hurricane was coming.

If the cotton wasn’t picked before the storm hit, an entire year’s profit could be destroyed.

Thomas drove his workers hard, as all planters did during harvest.

They rose before dawn and worked until darkness made it impossible to continue.

Celia was not in the fields.

Thomas had assigned her to work alongside old patients.

Within a week, even Hutchkins reported they had reached an understanding.

“Old patient says the new woman knows her business. Knows plants and remedies patients never heard of. Asked if she could start a proper herb garden.”

Thomas approved it, reasoning Celia would be under patients’ supervision.

The garden began as a small plot behind the quarters.

Come free for wounds, fever for headaches, willow bark for pain, chamomile for stomach ailments.

Each plant was labeled with neat handwriting, and Celia kept a journal documenting everything.

October brought the hurricane everyone expected.

It struck on the 12th, with massive winds that bent trees nearly horizontal and rain so thick visibility was impossible.

The storm lasted 18 hours.

When it passed, about 20% of the cotton had been destroyed and part of the quarter’s roof torn away.

Within two days of the hurricane, people began falling ill.

It started with children.

Fever, chills, violent coughing.

Then it spread to adults.

Within a week, 23 people were sick, including three house servants and Hutchkins’s wife.

Thomas sent to Savannah for a doctor.

The young physician who arrived looked overwhelmed immediately.

He prescribed rest, fluids, and regular doses of calamel.

“Keep them warm and dry. The fever should break in a week or so.”

After the doctor left, Thomas found Celia in the quarters, moving from patient to patient with patients trailing behind.

She had organized them efficiently, checking temperatures, listening to breathing, examining with practiced assessment.

“The doctor prescribed Calamel,” Thomas told her.

Celia didn’t look up. “Calamel makes it worse. Weakens them more than the fever does.”

“It’s what doctors use.”

“Doctors kill more people than they save.”

“You want these people to live so they can keep working? Let me treat them my way.”

Thomas should have been offended by her tone.

Instead, he asked, “What would you do differently?”

“No calam, willow bark tea for fever, honey and garlic for cough, elderberry to strengthen them.

Keep them hydrated with boiled water, not raw river water, and most important, keep the sickest ones separate.

This illness spreads through the air.

Group them too close, and you’ll lose everyone.”

It went against conventional wisdom, which held that diseases arose from bad air rather than spreading person to person.

But Thomas had noticed diseases did seem to cluster in patterns.

“Do it your way,” he said, “but if people start dying, it becomes your responsibility.”

“People dying is always someone’s responsibility, master. The question is whose?”

She organized the sick into three groups by severity, preparing teas and tonics carefully.

Within three days, fever began breaking in the first patients.

Within a week, all but two had recovered—both elderly, already weakened.

Under conventional treatment, Thomas suspected the death toll would have been far higher.

Word spread quickly.

By early November, Thomas received visits from neighboring planters wanting to borrow Celia’s services.

He agreed partly for neighborly relations and partly because the fees brought additional income.

Celia was sent to the Mansfield plantation for yellow fever, to the Rutled place for a difficult childbirth, to a farm near the Augichi River for a snake bite.

In each case, she succeeded where others would have failed.

Her reputation grew.

Celia could heal what others couldn’t.

But reputation is dangerous, especially for someone in Celia’s position.

People began remembering the Peton estate.

They wondered if someone who knew so much about healing might also know about the opposite.

Thomas heard these whispers but dismissed them.

Celia had been professional and effective since arriving.

She had saved his workers and earned him money.

Whatever had happened at Peton’s was passed.

December brought unusual cold, frost covering fields in the mornings.

The cotton harvest had been completed despite hurricane damage, and Thomas had sold his crop for a respectable price.

He began to relax, feeling he had navigated his first year without major disaster.

That was when the first sign appeared.

Hutchkins came to the main house one Tuesday morning, face pale and hands shaking.

“Mr. Puit, you need to come to the quarters now.”

A crowd had gathered near the quarter’s north end.

They parted when Thomas approached, revealing a symbol painted on the wall in what appeared to be blood or dark red clay.

The symbol was complex, a circle with lines radiating outward and smaller circles at specific points.

In the center was a handprint, adult-sized fingers spread wide.

“What is this?” Thomas demanded.

An older man named Daniel stepped forward. “It’s a warning sign, master. Old magic, African magic from before any of us were born.”

“My grandmother knew of such things. Said they were dangerous, that they called on powers that didn’t forget and didn’t forgive.”

“Who did this?”

Silence.

Then Daniel said carefully, “Don’t know, master, but signs like that usually mean someone’s working roots, calling on the old ways. And when someone works roots, bad things follow.”

Thomas ordered the symbol washed away and announced severe punishment for anyone caught painting such things.

But the damage was done.

Fear had entered Waverly.

Three days later, Hutchkins’s prize hunting dog was found dead near the well, body stiff and mouth foaming with dried saliva.

The dog had been healthy that morning.

“Poison,” Hutchkins said flatly. “Something fast-acting.”

A week before Christmas, a field worker named Samuel fell ill.

He complained of stomach pains that grew progressively worse.

By evening, he was vomiting violently, body convulsing.

Celia was summoned, but when she examined him, her expression grew grave.

“This isn’t natural illness. He’s been poisoned.”

Thomas felt his stomach drop.

“Poisoned? How?”

“Can’t say without knowing what he ate or drank, but the symptoms are consistent with several plant toxins.”

She looked at Thomas.

“The question isn’t what poisoned him. The question is who gave it to him.”

Samuel died three hours later in seizures.

It was a horrible death, and everyone witnessed some part of it.

The fear that had been spreading now exploded into near panic.

Thomas ordered an investigation, questioning everyone near Samuel that day.

The results were frustratingly inconclusive.

Samuel had eaten from the communal pot, drunk from the well.

He had no known enemies.

There was no apparent reason for anyone to want him dead.

Unless, Thomas thought with growing dread, Samuel wasn’t the intended target.

Unless someone was simply practicing, testing methods, preparing for something larger.

That night, Thomas couldn’t sleep.

He lay in bed listening to every creak, wondering what was happening on his plantation.

Someone had knowledge of poisons.

Someone was using it.

And despite his earlier confidence, Thomas found himself thinking again about the Peton estate and those four dead men.

Christmas at Waverly was subdued.

Thomas had planned to give the enslaved workers three days off with extra rations, but Samuel’s death had cast a pall over everything.

People accepted their gifts with muted thanks, avoiding eye contact, eager to return to the quarters where they felt safer in numbers.

On Christmas evening, Thomas heard a commotion from the quarters.

He grabbed his pistol and ran outside into the cold December night.

A crowd had gathered near the well, faces illuminated by torches.

At the center, two men restrained a young woman named Ruth.

She was fighting them, screaming words that didn’t quite make sense, eyes wide and unfocused.

“What’s happening?” Thomas demanded.

Hutchkins pushed through the crowd. “She tried to throw herself down the well, sir. Daniel and Joseph caught her just in time.”

Ruth was perhaps 19, a house servant who worked in the laundry.

Thomas had never known her to cause trouble.

“Ruth, what were you doing?”

She stopped struggling and turned toward him in torchlight.

Her face looked gaunt, almost skeletal.

“They’re coming for me. I can hear them. They’re in my head, telling me what I did, showing me what’s going to happen. I can’t make them stop. The only way to make them stop is to—”

She lunged toward the well again, but the men holding her were ready.

“She’s been like this for hours,” a house servant said.

“Started just after sunset, talking about voices and shadows and debts coming due.”

“Debts coming due.”

The same phrase Celia had used months ago.

Thomas felt cold that had nothing to do with the December temperature.

“Get her inside. Tie her down if necessary, and someone fetch Celia.”

But Celia was already there, standing at the crowd’s edge.

So still, Thomas hadn’t noticed.

She moved forward now, and the crowd parted for her.

“Let me see her,” Celia said.

Ruth’s eyes focused on Celia, and something like recognition crossed her face.

“You know, you understand. Tell them. Tell them what I did.”

“Hush now,” Celia said, her voice gentle in a way Thomas had never heard.

“No need to tell anyone anything. What’s done is done, and what’s coming will come regardless.”

“I didn’t mean for him to die,” Ruth sobbed.

“I was just so angry. He had no right to touch me like that. I just wanted him to hurt like he made me hurt. I didn’t know the mushrooms would kill him. I swear I didn’t know.”

The crowd went silent.

Thomas felt as if the ground had shifted.

“Ruth, are you saying you poisoned Samuel?”

But Ruth wasn’t looking at Thomas.

Her eyes were fixed on Celia, pleading and terrified.

“Make it stop, please. The voices, the shadows. Make them stop.”

Celia touched Ruth’s forehead with two fingers, a gesture that seemed almost ritualistic.

“Can’t stop what you started, child. You opened a door you didn’t know was there, and now you have to walk through it. All I can do is ease the journey.”

“What are you talking about?” Thomas demanded.

“What door?”

Celia ignored him.

She produced a small bottle from her pocket, uncorked it, and held it to Ruth’s lips.

“Drink this. It’ll calm the voices, quiet the shadows. You’ll sleep, and when you wake, you’ll be at peace.”

Ruth drank obediently.

Within minutes, her struggling ceased.

Her eyes closed.

Her breathing became slow and regular.

The men carried her to an empty cabin to be watched, and the crowd dispersed slowly, whispering.

Thomas grabbed Celia’s arm before she could leave.

“What did you give her?”

“Valyrian root, mostly chamomile, poppy extract—things to help her sleep. She confessed to murder. She confessed to being foolish. The girl had relations with Samuel she didn’t want. Got some mushrooms she thought would make him sick. Teach him a lesson. Didn’t realize the ones she picked were deadly. Easy to mistake if you don’t know what you’re looking for.”

Celia pulled her arm free.

“Now she’s eaten up with guilt. Seeing things that aren’t there. Hearing voices that don’t exist. Mind can do terrible things when it’s breaking under the weight of what it’s done.”

You seem to know a great deal about minds breaking.

Celia met his gaze steadily.

“I know about guilt, master. Know about what it does to people, how it twists them up inside until they can’t tell what’s real and what’s not. I know about debts and how they come due in ways people don’t expect.”

She walked away, leaving Thomas with more questions than answers and a growing certainty that he was in far deeper water than he had realized.

Ruth died two days later, still sleeping.

She simply stopped breathing during the night, peacefully by all accounts.

Celia examined her and declared it heart failure brought on by extreme distress.

The death was ruled natural, though several workers whispered that Ruth had been allowed to die, that Celia’s medicine had been something other than Valyrian.

Thomas didn’t know what to believe.

Ruth had confessed to Samuel’s murder, which should have brought clarity, but instead, it had only deepened the mystery.

How had an ignorant girl known which mushrooms to use?

Where had she learned about plant toxins?

The answer came slowly as Thomas observed Celia more carefully.

She wasn’t just a healer.

She was something older and more complex—a keeper of knowledge that predated American slavery, carried across the ocean in the memories of stolen people.

She knew herbs not just from books, but from generations of accumulated wisdom passed mother to daughter in secret.

And she was teaching others.

Thomas began to notice patterns.

Women who had been sick would spend time with Celia and emerge different, more confident, more knowing.

Ruth had been one of those women.

January brought bitter cold and an ice storm that coated everything in crystal.

The plantation operations slowed to a crawl.

During this forced confinement, Thomas finally took action he should have taken months earlier.

He broke into Celia’s cabin while she was away treating Hutchkins’s wife.

The cabin was meticulously organized.

Dried herbs hung from ceiling beams.

Each bundle labeled.

Bottles and jars lined shelves.

A worktable held mortar, pestle, measuring spoons, a small scale.

But there was more.

Hidden beneath the bed, Thomas found a wooden box wrapped in cloth.

Inside were notebooks, pages covered with Celia’s writing—medical notes mostly.

But interspersed were other entries written in a different tone.

Thomas read one dated October 15th.

“23 sick, 21 saved. The power to heal is the power to choose who lives. They don’t understand this. They think my knowledge belongs to them because they own my body. But knowledge can’t be owned. It can only be shared or withheld. I share it with those who deserve it. I withhold it from those who don’t. This is the only power I have, and I wield it carefully. Every life saved is a debt in my favor. Every death prevented is a weight on the scales. When the scales balance, justice will be served.”

Thomas’s hands shook as he turned pages, finding more entries in the same vein.

Celia was keeping a ledger of moral debts.

She was deciding who was worthy of healing and who was not.

Another entry dated December 20th: “The girl came to me in tears. Told me what the man did to her. Told me she wanted him to hurt. I gave her knowledge as I give all who ask and deserve. Not my place to judge what she does with it. She makes her own choices, faces her own consequences. But I also gave her something else. Guilt. Planted it deep with careful words. Guilt is slower than poison, but just as deadly. It eats from the inside, destroys the spirit before the body fails. She will not live long. This is mercy, though she doesn’t know it yet.”

Thomas closed the notebook carefully, his mind racing.

Celia hadn’t directly poisoned Samuel, but she had taught Ruth how, knowing what the girl intended.

Then she had driven Ruth to madness and death through psychological manipulation masked as spiritual counsel.

He continued searching and found, wrapped in oil cloth at the box’s bottom, a single sheet of yellowed paper covered with different handwriting.

“My daughter, if you are reading this, I am gone and you carry our knowledge alone. Remember what I taught you. The plants are neither good nor evil. They simply are. We choose how to use them. Use them to heal when the scales are balanced. Use them to harm when justice demands it. But always keep the ledger. Every life saved, every death allowed, every choice made must be recorded and remembered. This is our power and our burden. We are not slaves, though they call us such. We are keepers of the old knowledge, and that knowledge makes us free in ways they cannot understand or take from us.”

It was signed Phoebe and dated March 1838—the woman who had taught her daughter not just healing, but a philosophy of selective mercy and calculated revenge.

Thomas heard footsteps outside and barely had time to replace everything before Celia entered.

She stopped in the doorway, eyes moving from Thomas to the bed to the hidden box.

She knew.

“Your wife is asking for you, master,” Celia said quietly.

Thomas didn’t have a wife.

“Don’t you?”

“Then perhaps I misspoke. Hutchkins’s wife. I meant she’s asking for him. Wants to see him before the end.”

“The end?”

“The end that comes for us all, master. Some sooner, some later, but it always comes.”

She stepped into the cabin, closing the door.

“You’ve been in my things.”

There was no point denying it.

“I have.”

“Find what you were looking for?”

“I found notebooks, records, a letter from your mother. I know what you’ve been doing.”

Celia sat on the bed, moving with weariness.

When she spoke, her voice was soft but clear.

“My daughter’s name was Sarah. She was 17 when she got the pneumonia. Strong girl, smart, beautiful. Could have been anything if she’d been born free.”

She looked at Thomas, tears in her eyes for the first time.

“I watched my daughter die slowly over three days, watched the calamel poison her, watched the bloodletting drain what little strength she had. She died in agony, calling for me, and I couldn’t help because they had tied me up in the barn to teach me respect for white medicine.”

“I’m sorry,” Thomas said and meant it.

“Sorry doesn’t balance the scales, master. Sorry doesn’t bring her back or punish the man who killed her through negligence and pride.”

“So, I did what I had to do. Dr. Vance died from what looked like influenza complications. But it wasn’t influenza. It was Fox Glove, carefully administered over weeks in doses small enough to mimic heart problems.”

“Marcus died because he helped hold me down for the whipping. Kelly died because he laughed while they beat me. And Peton died because he owned us all—because he created the system that let my daughter die while I watched helplessly.”

She stood, facing Thomas directly.

“I’m not sorry for any of it. They deserved what they got. And if that makes me a murderer in your eyes, then so be it. But I’m also the woman who saved 21 people during the outbreak. I’m the woman who’s delivered 37 babies in the past year, losing only two. The scales balance, master. That’s all I’m trying to do. Balance the scales.”

Thomas felt trapped between horror and something like admiration.

What Celia had done was murder, cold and calculated.

But she had also saved countless lives.

Was she a monster or a healer?

Could she be both?

What about Ruth?

“Ruth came to me for help. I gave her knowledge. She made her own choices. But I also saw in her what I’ve seen in others who take a life—the guilt that comes after, the way it eats at the mind.

I gave her peace.

Master gave her a way out that was gentler than what she would have suffered otherwise.”

The cabin seemed darker, though the candle burned as brightly.

Thomas realized he stood at a crossroads.

He could report what he knew, try to have Celia arrested.

But he had no proof beyond notebooks that could be interpreted as philosophical musings.

And if he moved against her, who would care for Waverly’s sick?

What happens now?

Thomas asked finally.

“That depends on you, master. You can try to stop me, but you won’t succeed. Too many people depend on me. Trust me. Move against me, and you’ll have a rebellion. Or you can look the other way. Let the scales balance themselves and benefit from my skills. Your workers will be healthier, your profits higher. All it costs is your conscience and the lives of a few men who probably deserve what they get.”

And if one of those men is me?

Celia tilted her head, considering.

“Are you guilty of anything, master? Have you harmed someone who didn’t deserve it? Killed someone through negligence or cruelty? Because if you haven’t, you have nothing to fear from me. I don’t punish the innocent. I only balance the scales.”

Thomas thought about his treatment of the people he owned.

By slaveholding society standards, he was decent, but he was still a master, still participating in a system built on human bondage.

In Celia’s eyes, did that make him guilty?

“The Waverly plantation came to you from the previous owner,” Celia said softly.

“Did you ever wonder how he died?”

Thomas’s mouth went dry.

“Natural causes. That’s what I was told.”

“He did. Heart failure from years of hard living. I had nothing to do with it. I wasn’t here yet. But when Peton’s estate was liquidated, I knew where I would end up. Word travels among slaves faster than among masters. I knew Waverly was being sold to a new owner from Charleston. I knew you were young, inexperienced, ambitious. I knew you would need a skilled healer.”

She moved closer, so I made sure no one else bid on me.

“I told the other slaves what happened at Peton’s. Let them spread the word to their masters. Made myself seem dangerous, cursed, bad luck. All so that you, who didn’t know any better, would buy me cheap and bring me here where I could work, heal, teach, and yes, occasionally dispense justice that white courts won’t provide.”

“You manipulated me from the beginning.”

“I use the tools available to me, just like you use whips and chains and bills of sale to control us. We each have our weapons, master. Mine are just less obvious.”

Thomas realized he was trembling, whether from anger or fear, he couldn’t say.

“I could sell you, send you south, away from everyone you know.”

“You could try, but who would buy me now? Everyone from here to Mobile has heard the stories. And if you sold me, who would care for your sick? Who would deliver your babies? How many people would die before you found someone half as skilled?”

She smiled without warmth.

“I’ve made myself necessary, master. That’s the real power. Not the ability to kill, but the ability to save. People forgive almost anything from someone who can save lives.”

The truth struck Thomas like a physical blow.

Celia had made herself indispensable, and in doing so, secured a kind of freedom no legal document could provide.

She couldn’t be sold because she was too valuable.

She couldn’t be punished because too many people depended on her.

So what do you want from me?

Thomas asked finally.

“Nothing you aren’t already giving me. Freedom to practice my healing, access to herbs and plants, respect for my knowledge, and one more thing. Look the other way when the scales need balancing. Don’t ask questions you don’t want answers to. Don’t investigate deaths too closely. Let nature take its course.”

“Even when nature has a helping hand?”

“You’re asking me to be complicit in murder.”

“I’m asking you to be complicit in justice. There’s a difference, though I don’t expect you to see it. But think on this. How many slaves die every year from the cruelties of this system? How many are whipped to death, worked to death, bred like animals, sold away from families? And how many masters ever face punishment? The law protects you, not us. So we make our own justice in the only ways available to us.”

Thomas had no answer.

The moral foundation he had built his life on was cracking, revealing contradictions he had never wanted to examine.

He was a slave owner who considered himself humane, a participant in an inherently inhumane system.

“Get out,” he said quietly. “Leave me alone.”

Celia nodded and moved toward the door.

But before she left, she turned back.

“Hutchkins’s wife will die within a week. After that, Hutchkins will be different, quieter, less efficient. He’ll start drinking. The guilt of failing to save her will eat at him. You’ll need a new overseer within a year. I’d suggest promoting Daniel. He’s smart, fair, and the workers respect him.”

“How do you know all that?”

“Because I’ve seen it before. Grief follows predictable patterns, especially when mixed with guilt. Hutchkins knows deep down that he’s done bad things in his life. His wife’s death will make him confront that, and he won’t survive the confrontation.”

She walked away, leaving Thomas with more questions than answers and a growing certainty that he was in far deeper water than he had realized.

That night, Thomas stood alone in the cabin for a long time, surrounded by jars of dried herbs and bottles of tinctures, feeling as if he had just touched something ancient and dangerous that he would never fully understand.

That conversation in early January marked a turning point.

Thomas didn’t report what he had learned, didn’t try to sell Celia or restrict her movements, didn’t even confront her about Peton’s visit because doing so would be admitting he was afraid.

And a master who showed fear to his slaves had already lost the battle for control.

Summer progressed.

The cotton grew tall in the fields, and life at Waverly continued its rhythms.

But everything had changed.

Thomas saw it in the way the enslaved workers carried themselves with more confidence, more dignity.

He saw it in the way white planters approached Celia now with respect that bordered on fear.

He saw it in himself, in the way he had stopped thinking of himself as a master and started thinking of himself as merely the legal owner of property he no longer truly controlled.

The Civil War was coming.

Everyone could feel it.

The tension building between North and South felt like pressure before a storm.

South Carolina would secede, other states would follow, and the entire system that Waverly and plantations like it depended on would collapse.

Thomas found himself oddly at peace with that prospect.

He had seen an alternative system in action through Celia, one based on knowledge, skill, and moral authority rather than legal ownership and physical force.

When slavery ended, and it would end, Celia and people like her would thrive because their power came from what they knew and what they could do, not from chains and bills of sale.

In early September, as the cotton approached harvest time again, Thomas called Celia to his study one final time.

“I’ve decided to manumit you,” he said without preamble.

“I’m going to file paperwork giving you your freedom.”

Celia’s expression didn’t change.

“Why?”

“Because you’re already free. You have been since the day I bought you. Maybe before that. The paperwork will just make it official.”

“And what do you expect in return?”

“Nothing. Stay at Waverly. Leave. Do whatever you want. I’m not placing conditions on this.”

“There are always conditions, master.”

“Not this time. Consider it my attempt to balance my own scales. I participated in an evil system, profited from it, failed to oppose it when I should have. I can’t undo that, but I can at least free one person who should never have been enslaved in the first place.”

Celia was silent for a long moment, studying him.

Then slowly she smiled, and this time the warmth was genuine.

“You’ve learned something, master. Not everything I tried to teach you, but enough. Enough to survive what’s coming.

What is coming?”

“War, revolution, the end of everything you know. But you’ll survive it because you understand now that power isn’t about ownership. It’s about knowledge, skill, and the relationships you build with people who have reasons to keep you alive rather than dead.”

She stood to leave.

“I’ll stay at Waverly for now. These people need me, and I’m not done teaching yet. But I’ll stay as a free woman, not as your property. We’ll see how that changes things.”

The manumission papers were filed in October, making Celia legally free under Georgia law.

It caused talk throughout Chatham County.

“Why would a planter free such a valuable slave?”

But Thomas didn’t explain himself to anyone.

Celia continued her work, training more women in the healing arts, building her network of knowledge keepers, preparing for the day when the old system would fall and new systems would need to be built to replace it.

Thomas continued managing Waverly, but with a different understanding of his role.

He wasn’t the master of the plantation.

He was simply the person legally responsible for it, operating with the consent and cooperation of the people who actually did the work.

When that consent was withdrawn, as it would be once slavery ended, his authority would evaporate like morning mist.

The last entry in Thomas Puit’s diary, dated December 31st, 1859, read:

“I bought Celia for $12 and thought I had gotten a bargain.

Instead, I acquired something far more valuable and far more dangerous than I could have imagined.

A teacher who showed me the difference between legal authority and moral power, between ownership and control, between what the law permits and what conscience demands.

I don’t know if the lessons she taught me make me better or worse, innocent or complicit, saved or damned.

But I know I’m different than I was a year ago, and the world is different, too.

We’re all standing on the edge of something vast and terrible—a reckoning that’s been building for generations.

When it comes, I suspect people like Celia, the ones who’ve been keeping the old knowledge alive in secret, waiting for their moment, will be the ones who survive and perhaps even thrive.

As for me, I can only hope that when the scales finally balance, I’ve done enough to tip them toward mercy rather than justice.”

This mystery shows us that sometimes the most terrifying power isn’t violence or supernatural forces, but human knowledge wielded by someone with both the skill to heal and the will to judge.

The story of Celia and Thomas Puit reminds us that every system built on injustice carries within it the seeds of its own destruction and that those seeds are often cultivated by the very people the system sought to control.

News

How One Woman Saved Eminem’s Life—and Sparked a Movement of Hope! 🙌🔥

How One Woman Saved Eminem’s Life—and Sparked a Movement of Hope! 🙌🔥 The crowd at Detroit’s Ford Field…

Uncovered After 438 Years: The Shocking Truth Behind America’s Lost Colony! 🏝️😱

Uncovered After 438 Years: The Shocking Truth Behind America’s Lost Colony! 🏝️😱 Welcome to Beardy Bruce Lee Central! Today, we’re…

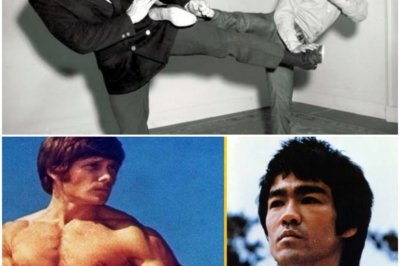

The Untold Story of Bruce Lee’s Training: Joe Lewis Finally Speaks After Decades🥋🔥

The Untold Story of Bruce Lee’s Training: Joe Lewis Finally Speaks After Decades🥋🔥 Welcome to Beardy Bruce Lee Central! Hey…

Inside Bruce Lee’s World: Chuck Norris Reveals Untold Stories of Their Legendary Fight 🥋🔥

Inside Bruce Lee’s World: Chuck Norris Reveals Untold Stories of Their Legendary Fight 🥋🔥 Welcome to Beardy Bruce Lee Central!…

The Untold Story of Diana and Camilla — What the Royal Chef Saw Will Shock You

The Untold Story of Diana and Camilla — What the Royal Chef Saw Will Shock You In a stunning revelation,…

Luxury, Fear, and Tyranny: Hitler’s Maid Finally Exposes Life Behind Closed Doors at the Berghof

Luxury, Fear, and Tyranny: Hitler’s Maid Finally Exposes Life Behind Closed Doors at the Berghof Today, the Hamburg radio announced…

End of content

No more pages to load