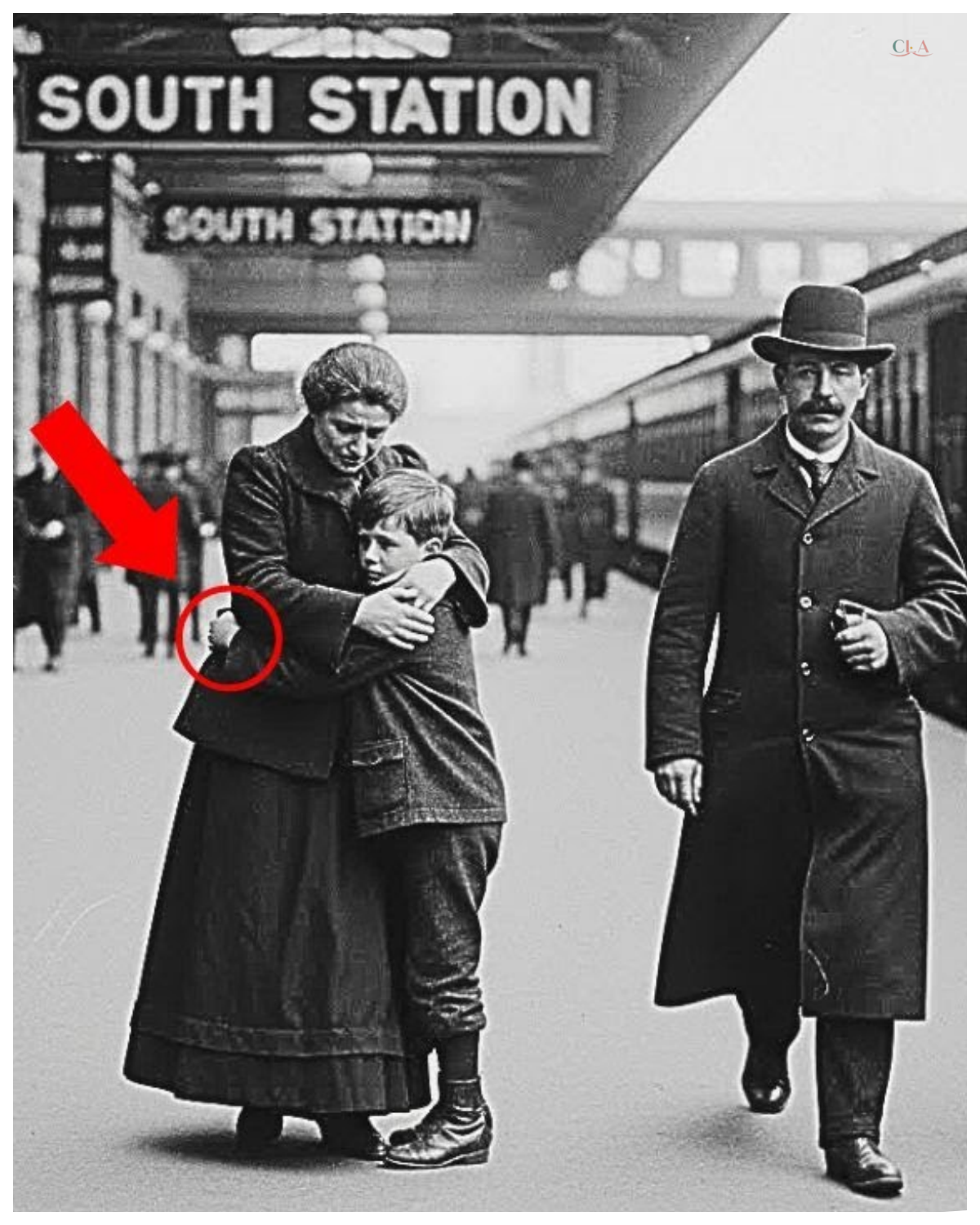

Why were historians speechless when they enlarged this portrait of a mother and her son from 1900? In the summer of 2018, Dr.Rebecca Torres sat in the dimly lit archives of Harvard University’s Widner Library, surrounded by boxes of deteriorating photographs from the turn of the century.

As a historian specializing in immigration and labor movements in early 20th century America, she had spent countless hours examining images of working-class families, hoping to piece together the untold stories of those who built the nation from the shadows.

The air smelled of old paper and preservation chemicals, a scent she had grown to associate with discovery.

That afternoon, Rebecca carefully lifted a fragile photograph from a Manila envelope marked Boston Railway Station collection, 1900, 1905.

The image showed a woman in a dark worn dress embracing a young boy, perhaps 8 years old, on what appeared to be a train platform.

The woman’s face was turned downward, her expression hidden, but her posture conveyed unmistakable sorrow.

The boy stared directly at the camera with hollow, tired eyes that seemed far too old for his small frame.

Rebecca had seen hundreds of similar photographs.

Immigrants, laborers, families torn apart by circumstance.

But something about this particular image held her attention.

She couldn’t quite identify what it was.

The composition was simple, almost mundane.

Yet, there was an intensity to the moment captured, a weight that seemed to transcend the faded sepia tones.

She made a note to include it in the university’s ongoing digitization project, which used advanced scanning technology to preserve and restore historical photographs.

The process involved highresolution imaging that could reveal details invisible to the naked eye, bringing new life to forgotten moments in history.

3 weeks later, Rebecca received an email from the digitization team with the subject line, “Unusual finding in item nogarter 1847.

” Curious, she opened the message and downloaded the attached highresolution scan.

As the image loaded on her screen, she leaned forward, adjusting her glasses.

The clarity was remarkable.

She could see individual threads in the woman’s dress, the grain of the wooden platform beneath their feet, even the texture of the boy’s worn boots.

But it was something else that made Rebecca’s breath catch in her throat.

In the boy’s small hand, pressed against the folds of his mother’s dress and nearly invisible in the original photograph, was an object she hadn’t noticed before.

She zoomed in further, her heart beginning to race.

It was a small metallic disc catching the light just enough to be visible in the enhanced image.

A metal of some kind.

Rebecca reached for her phone, her hands trembling slightly.

This was no ordinary family portrait.

This was something else entirely.

Rebecca immediately contacted her colleague, Dr.

James Mitchell, a military historian who specialized in American conflicts of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Within an hour, he was standing beside her desk, studying the enlarged image on her computer screen with intense concentration.

The overhead lights in the archive room cast sharp shadows across the photograph, making the hidden metal seem almost to glow with significance.

“Can you make it any clearer?” James asked, leaning so close to the monitor that his breath fogged the screen slightly.

Rebecca adjusted the contrast and sharpness settings using specialized software designed for historical image restoration.

The metal became more distinct with each adjustment, revealing faint engravings on its surface.

James fell silent for a long moment, his eyes narrowing as he studied the details.

That’s a military medal, he finally said, his voice quiet but certain.

The shape, the ribbon attachment point.

Rebecca, I think that’s from the SpanishAmerican War era, 1898, maybe 1899.

Rebecca felt a chill run down her spine.

The photograph was dated 1900, just 2 years after the conflict that had established America as a global power.

But why would a young boy be clutching a military medal in such a clandestine way, hidden against his mother’s dress? And why did the mother appear so devastated? Can you identify the specific metal? Rebecca asked, already pulling up military records databases on her second monitor.

James shook his head slowly, frustrated by the limitations of the image quality despite the technological enhancement.

Not with absolute certainty, but the size and shape are consistent with campaign medals issued to soldiers who served in Cuba or the Philippines.

We need to find out who these people were.

He paused, running a hand through his graying hair.

Rebecca, if this boy was holding his father’s medal and his mother is clearly in mourning, we might be looking at a widow and an orphan.

Rebecca’s mind raced through possibilities.

Thousands of men had served in the Spanishamean War.

And while American casualties were relatively low compared to other conflicts, many soldiers had died, not just from combat, but from disease, particularly yellow fever and malaria.

The war had been brief, but brutal, and its aftermath had left countless families shattered.

The photograph was taken at a Boston railway station, Rebecca said, opening the original archive notes.

There’s a partial notation here.

Mother and child, platform 7, early morning departure.

That’s all we have.

No names, no destination, nothing else.

James pulled up a chair beside her, his expression determined.

Then we start with the station itself.

Boston in 1900 had several major railway terminals.

We need to identify which one.

Check passenger manifests if they still exist.

cross reference with military discharge records and casualty lists from the war.

Rebecca nodded, feeling the familiar rush of a historical mystery beginning to unfold.

But this wasn’t just an academic puzzle.

This was about real people, real grief, and a secret hidden in plain sight for over a century.

As she looked again at the boy’s solemn face, and the metal clutched desperately in his small hand, she felt a profound responsibility to uncover the truth.

“Let’s find out who they were,” she said softly.

and why this medal was so important that he carried it like that.

For the next two weeks, Rebecca and James worked tirelessly dividing their efforts between different research avenues.

Rebecca focused on identifying the railway station and searching for immigration and passenger records, while James dove deep into military archives, searching for Irish immigrant soldiers who had served in the Spanishame War and died or gone missing shortly afterward.

The work was painstaking and often frustrating.

Many records from that era had been lost to fires, floods, or simple neglect.

Immigration documentation was incomplete, and the military’s recordkeeping for enlisted men, especially those from immigrant backgrounds, was notoriously inconsistent and sometimes deliberately careless.

Rebecca started with the photograph itself, examining every visible detail for clues.

The architectural elements visible in the background, the iron support beams, the distinctive roof line, the platform numbering system, eventually led her to identify the location as South Station, which had opened in Boston in 1899.

It was one of the busiest railway terminals in New England, serving thousands of passengers daily, many of them immigrants moving between cities in search of work.

She requested access to South Station’s historical archives, now held by the Massachusetts Historical Society.

After days of searching through fragile ledgers and passenger logs, she found a notation dated September 14th, 1900.

Platform 7, morning departures to Providence, Hartford, New York.

But there were no passenger names listed for that specific date.

The records had been kept primarily for operational purposes, not detailed passenger tracking.

Meanwhile, James was making slow but steady progress through military records.

He obtained access to the National Archives collection of Spanishamean War Service records, focusing on soldiers of Irish descent who had enlisted from Massachusetts.

The lists were long.

Immigration and military service had often gone handinand with young men seeing the army as a path to acceptance and citizenship.

One afternoon, James called Rebecca from the National Archives reading room in Washington.

His voice carried a mixture of excitement and sadness.

“I found something,” he said.

There were 47 Irishborn soldiers from the Boston area who died during or immediately after the SpanishAmerican War.

But here’s what’s strange.

12 of them have notations in their files marked status disputed or record incomplete.

Rebecca’s pulse quickened.

Disputed how? Various reasons.

Some were listed as deserters, others as missing an action, a few with contradictory death reports.

The paperwork is a mess, Rebecca.

And given the anti-immigrant sentiment of the time, I suspect some of these men were simply forgotten, or worse, deliberately misrecorded.

Rebecca thought of the medal hidden in the boy’s hand, the mother’s griefstricken posture.

If a soldier was wrongly listed as a deserter, his family wouldn’t receive his pension or benefits.

They’d be left with nothing but shame.

Exactly, James replied.

And if this boy’s father was one of those men, that medal might have been the only proof the family had of his actual service and sacrifice.

I’m sending you the list of names.

Let’s see if we can match any of them to immigration records or Boston city directories from 1898 to 1900.

Rebecca received James’ list and immediately began cross-referencing the names with Boston immigration records, city directories, and church registries.

The process was meticulous and exhausting, requiring her to visit multiple archives across the city.

She spent long days in dusty basement and cold storage facilities, carefully turning pages of century old documents, searching for connections.

On the fourth day of her search, while examining records at the arch dascese of Boston’s historical archives, Rebecca found something promising.

In a parish registry from St.

John Augustine’s church in South Boston, an area heavily populated by Irish immigrants, she discovered a baptismal record from 1892 for a boy named Thomas, son of Patrick and Mary, immigrants from County Cork.

The surname caught her attention immediately.

She checked it against James’ list of disputed military records.

There it was, Patrick, enlisted August 1898.

Company K, Second Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, deployed to Cuba.

Status: Deserted, October 1898.

Um, Rebecca’s hands trembled as she photographed the registry page with her phone.

A deserter.

That single word would have destroyed this family’s reputation, cut off any military benefits, and branded Patrick as a coward in the eyes of his community.

But the medal in the photograph suggested a very different story.

She called James immediately.

I think I found them.

Patrick, Mary, and their son Thomas.

The father was listed as a deserter, but if he actually died in combat and someone made an error, or worse, deliberately falsified the record, this family would have been devastated.

James’ response was thoughtful.

We need to find Patrick’s complete military file.

If there’s documentation about how he supposedly deserted, there might also be evidence that contradicts it.

Sometimes these files contain letters, witness statements, or transfer orders that tell a different story than the official designation.

Over the next week, James worked with archivists at the National Archives to locate Patrick’s full military record.

What he discovered was deeply troubling.

The desertion charge was based on a single report filed by a lieutenant named Howard Sterling, who claimed that Patrick had abandoned his post during a skirmish near Santiago to Cuba in October 1898.

There was no investigation, no corroborating testimony, no follow-up.

But buried deeper in the file, James found something else.

A handwritten note from a different officer, Captain William Harrison, dated November 1898.

It read, “Regarding the man Patrick reported as deserter by Latine Sterling, witnessed this soldier fall during enemy engagement, Oct four.

Body not recovered due to terrain.

Recommend status review.

James sat back in his chair, anger rising in his chest.

Patrick hadn’t deserted.

He had died in combat, but Lieutenant Sterling’s report had been accepted as official, and Captain Harrison’s contradicting account had been ignored or overlooked.

The bureaucratic indifference or perhaps prejudice had condemned an immigrant soldier’s memory and destroyed his family’s future.

“Rebecca,” James said when he called her that evening, his voice heavy with emotion.

“Patrick died a hero, and his family spent the rest of their lives carrying the shame of a lie.

” With Patrick’s identity confirmed in the truth about his death emerging.

Rebecca shifted her focus to understanding what had happened to Mary and Thomas after 1900, she knew that the photograph captured a moment of departure.

But where had they been going and why? She returned to South Boston, walking the narrow streets that Mary would have known, trying to imagine the widow’s life in those desperate years.

The neighborhood had changed dramatically, but some buildings from that era still stood, their brick facades weathered, but enduring.

At the Boston Public Library, Rebecca discovered city directory listings that painted a heartbreaking picture.

In 1899, Mary was listed as living at a tenement address on East 4th Street.

Occupation Laundress.

By 1900, she had moved to a smaller, cheaper lodging on West Broadway.

By 1901, her name no longer appeared in the Boston directories at all.

Rebecca also found records at the Massachusetts State Archives showing that Mary had applied for a military widow’s pension in early 1899.

The application had been denied because Patrick’s status was listed as deserter.

Mary had appealed twice, each time submitting handwritten letters pleading for someone to investigate the circumstances of her husband’s death.

Both appeals were rejected with form letters.

The weight of this injustice pressed heavily on Rebecca as she read Mary’s words written in careful but imperfect English.

My husband Patrick was good man.

He loved his country.

He go to war proud.

Please I need help from my boy.

Please look again.

He not run away.

He died fighting.

No one had listened.

Rebecca found more fragments of the story in unexpected places.

A notation in the records of the saint.

Vincent Depal Society, a Catholic charity organization, showed that Mary had requested assistance in August 1900 to pay for her son’s railway ticket to Providence, Rhode Island.

The notation indicated she was sending the boy to live with her sister’s family because she could no longer afford to feed him.

The photograph suddenly made complete sense.

It was a mother’s goodbye, a moment of unbearable separation forced by poverty and injustice.

Mary was sending away her only child, the last piece of Patrick she had left because a bureaucratic error or deliberate discrimination had robbed her of her husband’s pension and her ability to survive.

But the medal, why had Thomas been holding it in that moment? Rebecca found a possible answer in an unlikely source.

A small diary entry from a Providence City Mission volunteer archived at the Rhode Island Historical Society.

The entry dated September 1900 mentioned a boy named Thomas arriving from Boston to stay with his aunt’s family.

The child carries with him a military medal, which he says his mother gave him before the train.

She told him it belonged to his father, who was a soldier and a brave man, and that he must never forget this truth, no matter what anyone else says.

Rebecca sat alone in the reading room, tears blurring her vision.

Mary had given Thomas the medal, the only physical proof of Patrick’s service and honor, as a final gift, a piece of truth to carry with him when everything else had been taken away.

It was an act of profound love and defiance.

James, meanwhile, had become increasingly troubled by Lieutenant Howard Sterling, the officer who had filed the desertion report.

Something about the situation didn’t sit right with him.

A single uncorroborated accusation of desertion, a contradicting witness statement ignored, and no formal investigation.

It all seemed too convenient, too final.

He decided to research Sterling’s background and military career.

What he discovered painted a disturbing picture.

Sterling came from a wealthy Boston family with deep political connections.

He had attended Harvard and received his commission through family influence rather than merit or training.

His service record showed a pattern of friction with enlisted men, particularly those from immigrant backgrounds.

James found several disciplinary complaints filed against Sterling by fellow officers, alleging that he showed favoritism towards soldiers from established American families and treated immigrant soldiers with contempt.

One report filed by Captain Harrison, the same officer who had witnessed Patrick’s death, accused Sterling of conduct unbecoming an officer and prejuditial treatment of men under his command.

But Sterling’s family connections had protected him.

The complaints were dismissed and he completed his service without consequence.

After the war, he returned to Boston where he pursued a career in business and local politics, eventually serving on the city council in the 1910s.

James found something else in Sterling’s post-war correspondence archived at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

In a letter to a friend dated 1899, Sterling wrote casually about his time in Cuba.

The immigrant rabble proved as unreliable as expected.

One Irish fool got himself killed trying to play hero.

I marked him down as a deserter, saved the government a pension, and taught the others a lesson about their place.

James felt sick reading those words.

Patrick hadn’t just been failed by bureaucracy.

He had been deliberately dishonored by a bigoted officer who saw immigrant soldiers as expendable and unworthy of respect.

The desertion report wasn’t an error.

It was an act of malice.

He immediately shared his findings with Rebecca.

Her response was immediate and fierce.

We have to set this right.

We have to tell Patrick’s story and clear his name, even if it’s more than a century late.

But James had concerns.

Sterling’s descendants might still be prominent in Boston.

We need to be careful about how we present this.

We have documentation, but we also need to consider the implications of accusing a historical figure of what amounts to a hate crime against an immigrant soldier.

Rebecca understood his caution, but her resolve was unwavering.

This isn’t about destroying Sterling’s legacy.

It’s about restoring Patrick’s.

Mary and Thomas lived with that shame for the rest of their lives.

If we can give them back their truth, we have to.

James nodded slowly.

Then we need to find out what happened to them.

If Thomas is still alive or if there are descendants, they deserve to know the real story.

Tracing Thomas’ life after 1900 proved challenging but not impossible.

Rebecca traveled to Providence, where she accessed local records, school registries, and church documents, she discovered that Thomas had lived with his aunt’s family, his mother’s sister, and her husband in a working-class neighborhood near the Providence River.

School records from the Central Street School showed that Thomas attended classes intermittently between 1901 and 1905, often missing weeks at a time, likely because he was working to help support his aunt’s family.

Teachers notes described him as quiet, serious beyond his years, hardworking when present.

In 1906, when Thomas would have been 14, he appeared in Providence City Records as an apprentice at a textile mill, one of the many factories that dominated the city’s economy.

Rebecca found his name in employment ledgers, tracking his progression from apprentice to skilled worker over the following years.

But what happened to Mary? Rebecca returned to Boston records, searching for any trace of Thomas’s mother after 1900.

It took days of searching through death records, hospital admissions, and poor house registries before she found the heartbreaking answer.

Mary had died in February 1902 at Boston City Hospital.

The cause of death was listed as pneumonia and exhaustion.

She was 31 years old.

The notation indicated she had been brought to the hospital from a lodging house where she worked as a cleaning woman, her condition already critical.

She died alone with no family listed, no possessions noted except the clothes she wore.

Rebecca sat in the archive room, overwhelmed by sadness.

Mary had given up her son to give him a chance at survival, then worked herself to death in the two years that followed.

Did Thomas know his mother had died? Had anyone told him? She found the answer in an unexpected place.

A letter preserved in the archives of the Rhode Island Catholic Orphan Asylum.

It was written by Thomas’s aunt to the Dascese of Providence in March 1902 requesting assistance because she could not afford to continue caring for her nephew now that his mother had passed away.

The letter mentioned that Thomas had been informed of his mother’s death and was inconsolable.

The asylum records showed that Thomas had been admitted in April 1902 at age 10 and remained there until 1906 when he was old enough to work full-time.

The years between his mother’s goodbye at the train station and his entry into the orphanage, the brief time he had spent with his aunt’s family, had been the last semblance of family he would know for years.

Yet through all of this, Rebecca noticed something remarkable in the institutional records.

Multiple mentions of a military medal that Thomas kept with him, carefully hidden in his few possessions.

The orphanage’s intake inventory from 1902 listed it.

One small military medal, brass, worn ribbon, property of the boy.

He had kept it through everything.

the separation from his mother, her death, his time in the orphanage.

Thomas had kept his father’s medal, just as Mary had wanted.

It was the physical embodiment of a truth he refused to let die.

Rebecca’s research into Thomas’s adult life revealed a man shaped profoundly by his childhood losses.

After leaving the orphanage in 1906, he worked in Providence’s textile mills for several years before enlisting in the US Army in 1917 when America entered World War I.

He was 25 years old.

His enlistment records preserved at the National Archives showed that he listed his father’s name and service history, noting KIA Cuba, 1898 rather than accepting the official desertion designation.

It was a quiet act of defiance, a refusal to accept the lie that had destroyed his family.

Thomas served honorably in France with the 26th Infantry Division, seeing combat in several major engagements.

He was wounded twice but survived the war and returned to Providence in 1919.

James found his discharge papers which included a commenation for bravery under fire.

Like his father, Thomas had proven himself a courageous soldier.

After the war, Thomas married a woman named Catherine in 1921.

Rebecca found their marriage certificate and Providence records.

They had three children, two daughters, and a son, born between 1922 and 1928.

Thomas worked as a foreman at a textile mill, providing his family with a stable, working-class life.

But Rebecca found something else that revealed how deeply the past had marked Thomas.

In a collection of personal papers donated to the Providence Public Library by one of his descendants, she discovered a journal Thomas had kept during the 1930s.

The entries were sparse and practical, mostly notes about work and family matters.

But one entry stood out.

It was dated September 14th, 1940, exactly 40 years after the photograph at South Station.

Thomas had written, “Today I thought of the day Mother sent me away.

I was 8 years old and terrified.

She put father’s medal in my hand and told me to remember that he was brave and good no matter what the government said.

She was crying but trying to hide it.

I knew even then I might not see her again.

I carry that medal still.

My children know the story.

They will pass it to their children.

The truth will not die with me.

Rebecca’s throat tightened reading those words.

Thomas had made it his life’s mission to preserve his father’s true story, to pass it down through generations, ensuring that Patrick’s honor would outlive the lie that had condemned him.

She discovered that Thomas had died in 1964 at age 72, survived by his wife, children, and several grandchildren.

His obituary in the Providence Journal made no mention of his father’s service, or the family’s history, but it noted that he was a devoted father and grandfather, a veteran of World War I, and a man of quiet dignity and unshakable principles.

Now, Rebecca faced a crucial question.

Did any of Thomas’s descendants still live in the area? And if so, would they know about the metal, the photograph, and the story Thomas had been so determined to preserve? Rebecca began searching for Thomas’s living descendants, starting with the most recent generations.

Using genealological databases, obituary records, and public documents, she traced his family line forward through the decades.

His son had died in 1998, but both of his daughters had lived into the 2000s, and they had children and grandchildren scattered across New England.

After weeks of careful research and discreet inquiries, Rebecca made contact with a woman named Sarah Thomas’s granddaughter who lived in Cranston, Rhode Island, just outside Providence.

She was 71 years old, retired from a career as a public school teacher, and initially skeptical when Rebecca reached out via email explaining her research.

My grandfather didn’t talk much about his childhood.

Sarah wrote in her first response.

It was clearly painful for him, but he did tell us about his father, the soldier who died in Cuba, and he always insisted the official records were wrong.

He kept a metal in a wooden box.

I remember seeing it as a child.

Rebecca’s heart raced reading those words.

The metal still existed.

After more than a century, the physical evidence of Patrick’s service had survived.

With Sarah’s permission, Rebecca and James drove to Cranston on a cold November morning in 2018.

Sarah welcomed them into her modest home, a comfortable house filled with family photographs spanning generations.

She offered them tea and settled into her living room armchair with a mixture of curiosity and caution.

Before I show you anything, Sarah said carefully, I need to understand what you’re trying to do.

My grandfather protected his father’s memory fiercely.

If this is just academic research that will end up in some dusty archive, I’m not sure I want to participate.

Rebecca understood her concern.

She explained everything they had discovered.

The photograph, the hidden medal, Patrick’s wrongful desertion designation, Lieutenant Sterling’s prejudice, Mary’s desperate struggle and early death, Thomas’s determination to preserve the truth.

She showed Sarah the documents, the letters, the military records.

Sarah listened in silence, her eyes filling with tears as the full scope of her family’s tragedy became clear.

When Rebecca finished, Sarah stood without a word and left the room.

She returned moments later carrying a small wooden box, its surface worn smooth by generations of handling.

“My grandfather gave this to my father before he died,” Sarah said softly, placing the box on the coffee table.

“My father gave it to me.

I’ve been waiting my whole life to know what to do with it.

” She opened the box.

Inside, resting on faded velvet, was the medal from the photograph.

Even after 120 years, it retained a faint gleam.

The engraving was still visible.

A campaign medal for service in Cuba issued to soldiers of the Spanishame War.

On the back, someone had carefully scratched a name.

Patrick.

He was a brave man, Sarah said, touching the medal gently.

My grandfather told me that again and again.

He said his mother made him a promise never to forget it, and he never did.

He passed that promise to us.

James carefully photographed the medal, documenting every detail.

Rebecca explained what they hoped to do next.

Publish their findings, formally petitioned the Department of Defense to review Patrick’s service record, and restore his honorable status postumously.

More than a century late, James added, “But still meaningful.

Your great great-grandfather deserves to have his name cleared.

” Sarah looked at the medal, then at the researchers who had uncovered her family’s buried truth.

“Do it,” she said firmly.

“Whatever it takes.

Let’s finish what my great-grandmother started when she put this medal in my grandfather’s hand.

Over the following months, Rebecca and James worked with military historians, legal advocates, and the Department of Defense’s board for correction of military records to build a comprehensive case for Patrick’s postumous exoneration.

They submitted every piece of evidence they had gathered.

Captain Harrison’s witness statement, Sterling’s prejuditial correspondence, Mary’s pension appeals, and the medal itself, which Sarah had agreed to loan for authentication.

The process was bureaucratic and slow, but the evidence was overwhelming.

In June 2019, nearly 121 years after Patrick’s death in Cuba, the Department of Defense issued a formal correction to his military record.

His status was changed from deserted to killed in action, and he was postumously awarded the recognition he had earned in 1898.

Rebecca organized a small ceremony at the Massachusetts State House in August 2019, inviting Sarah and her family, military officials, and representatives from Irish-American veterans organizations.

The atmosphere was solemn and deeply emotional as a military officer presented Sarah with her great great-grandfather’s corrected service record and a certificate of honorable service.

Patrick served his country with courage and died with honor.

The officer said, “The error in his record was a grave injustice to him and his family.

Today, we set that record straight.

” Sarah accepted the documents with trembling hands, tears streaming down her face.

Beside her stood her children and grandchildren, Patrick’s descendants, carrying forward the line he had died protecting.

They had brought the medal, which rested in its wooden box on a small table draped with an American flag.

Rebecca spoke briefly at the ceremony, telling the story of the photograph, the hidden medal, and the family’s century long fight for truth.

She described Mary’s sacrifice, Thomas’s determination, and the unbroken chain of memory that had preserved Patrick’s honor through five generations.

This photograph, Rebecca said, holding up a large print of the 1900 image, captured one of the most painful moments in this family’s history.

A mother saying goodbye to her son, both of them carrying the weight of an injustice they couldn’t fight.

But hidden in that moment was also an act of profound resistance.

A medal passed from hand to hand, a truth preserved against all odds.

She looked at Sarah.

Your great great grandmother Mary wanted her son to remember that his father was brave and good.

She gave him the only proof she had, and he kept that promise.

Today, finally, the world knows the truth, she protected.

After the ceremony, Sarah approached Rebecca and James privately.

I have something to tell you, she said.

My grandfather kept a journal.

I found an entry from September 1940 where he wrote about the day his mother gave him the medal.

He wrote, “The truth will not die with me.

” I used to think that was just his way of coping with grief.

Now, I understand it was a mission, and you helped him complete it.

The photograph that had hung forgotten in an archive for 118 years now held a place of honor in Harvard’s collection, accompanied by the full story of the family it depicted.

The medal returned to Sarah’s family, where it would continue to be passed down, no longer a symbol of hidden truth, but of justice finally served.

Rebecca often thought about Mary standing on that platform in 1900, pressing the medal into her son’s hand, whispering words of truth and love she knew he would need to survive.

Maria died believing her husband was remembered only as a deserter, never knowing that her final gift to her son would one day restore everything that had been taken from them.

But Thomas had known.

He had carried that medal for 64 years, protecting his father’s honor with the same courage Patrick had shown in Cuba.

And now, five generations later, the truth had finally caught up with the lie.

The photograph remained as it had always been, a mother comforting her son, frozen in a moment of grief.

But now, when people looked at it, they could see what had been hidden for so long.

A small hand clutching a metal, holding tight to love, memory, and an unshakable belief that the truth, no matter how long buried, would someday come to

News

🚛 HIGHWAY CHAOS — TRUCKERS’ REVOLT PARALYZES EVERY LAND ROUTE, KHAMENEI SCRAMBLES TO CONTAIN THE FURY 🌪️ The narrator’s voice drops to a biting whisper as convoys snake through empty highways, fuel depots go silent, and leaders in Tehran realize this isn’t just a protest — it’s a nationwide blockade that could topple power and ignite panic across the region 👇

The Reckoning of the Highways: A Nation on the Edge In the heart of Tehran, the air was thick with…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Darkened City: A Night of Reckoning In the heart of Moscow, a city that once stood proud and unyielding,…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Shocking Resurrection: A Hollywood Revelation In a world where faith intertwines with fame, the announcement sent ripples through the…

🎬 “TO THIS DAY, NO ONE CAN EXPLAIN IT” — JIM CAVIEZEL BREAKS YEARS OF SILENCE ABOUT THE MYSTERY THAT HAUNTED HIM AFTER FILMING ⚡ In a hushed, almost trembling confession, the actor leans back and stares past the lights, hinting at strange accidents, eerie coincidences, and moments on set that felt less like cinema and more like something watching from the shadows, leaving even hardened crew members shaken to their core 👇

The Unseen Shadows: Jim Caviezel’s Revelation In the dim light of a secluded room, Jim Caviezel sat across from the…

📜 SEALED FOR CENTURIES — ETHIOPIAN MONKS FINALLY RELEASE A TRANSLATED RESURRECTION PASSAGE, AND SCHOLARS SAY “NOTHING WILL BE THE SAME” ⛪ The narrator’s voice drops to a breathless whisper as ancient parchment cracks open under candlelight, hooded figures guard the doors, and words once locked inside stone monasteries spill out, threatening to shake faith, history, and everything believers thought they understood 👇

The Unveiling of Truth: A Resurrection of Belief In the heart of Ethiopia, where the ancient echoes of faith intertwine…

🕯️ FINAL CONFESSION — BEFORE HE DIES, MEL GIBSON CLAIMS TO REVEAL JESUS’ “MISSING WORDS,” AND BELIEVERS ARE STUNNED INTO SILENCE 📜 The narrator’s voice drops to a hushed, dramatic whisper as old notebooks open, candlelight flickers across ancient pages, and Gibson hints that lines never recorded in scripture could rewrite everything the faithful thought they knew 👇

The Unveiling of Hidden Truths In the dim light of his private study, Mel Gibson sat surrounded by piles of…

End of content

No more pages to load