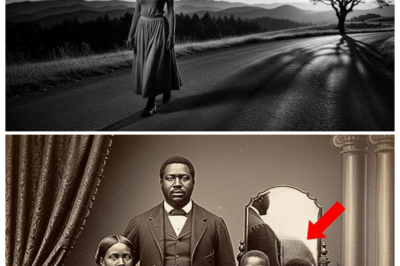

Why were historians shocked when they enlarged this 1860 family photo?

The photograph arrived at the Virginia Museum of History in a cedar box wrapped in silk that had yellowed with age.

Dr.Sarah Chen, the museum’s lead curator for Civil War collections, lifted it carefully from its protective casing.

The Dgero type was remarkably well preserved, its silver surface still reflecting light after more than a century and a half.

Five people stared back at her from 1860.

A prosperous white family, clearly wealthy, judging by their clothing and the elaborate studio setting.

The patriarch sat in the center, a stern-faced man in his 50s with a thick beard and dark suit.

His wife stood beside him, one hand resting on his shoulder, her dressed in elaborate creation of silk and lace.

Three young men, presumably their sons, completed the composition.

Two standing behind their parents, one seated to the father’s left.

Sarah had examined thousands of antabbellum photographs.

This one followed all the conventions, formal poses, serious expressions, the careful arrangement of bodies to demonstrate family hierarchy and respectability.

The photographer had written on the back in faded ink, “The Harrison family, Richmond, Virginia.

March 1860.

” March 1860.

Sarah felt a chill.

That date placed the photograph just one year before the Civil War began in the heart of what would become the Confederate capital.

Richmond had been a center of slave trade, a city where fortunes were built on the buying and selling of human beings.

She set the Dgeray on her examination table and adjusted the magnifying lamp.

The donor’s note had said the photograph came from an estate sale, part of a collection belonging to descendants who’d moved north decades ago.

No other information had been provided.

Sarah began her standard analysis, noting details that would help with historical context.

The father’s clothing suggested merchant-class wealth, expensive but not aristocratic.

The mother’s jewelry was tasteful, valuable.

The sons, ranging from perhaps 18 to 30 years old, wore matching dark suits that indicated family unity and prosperity.

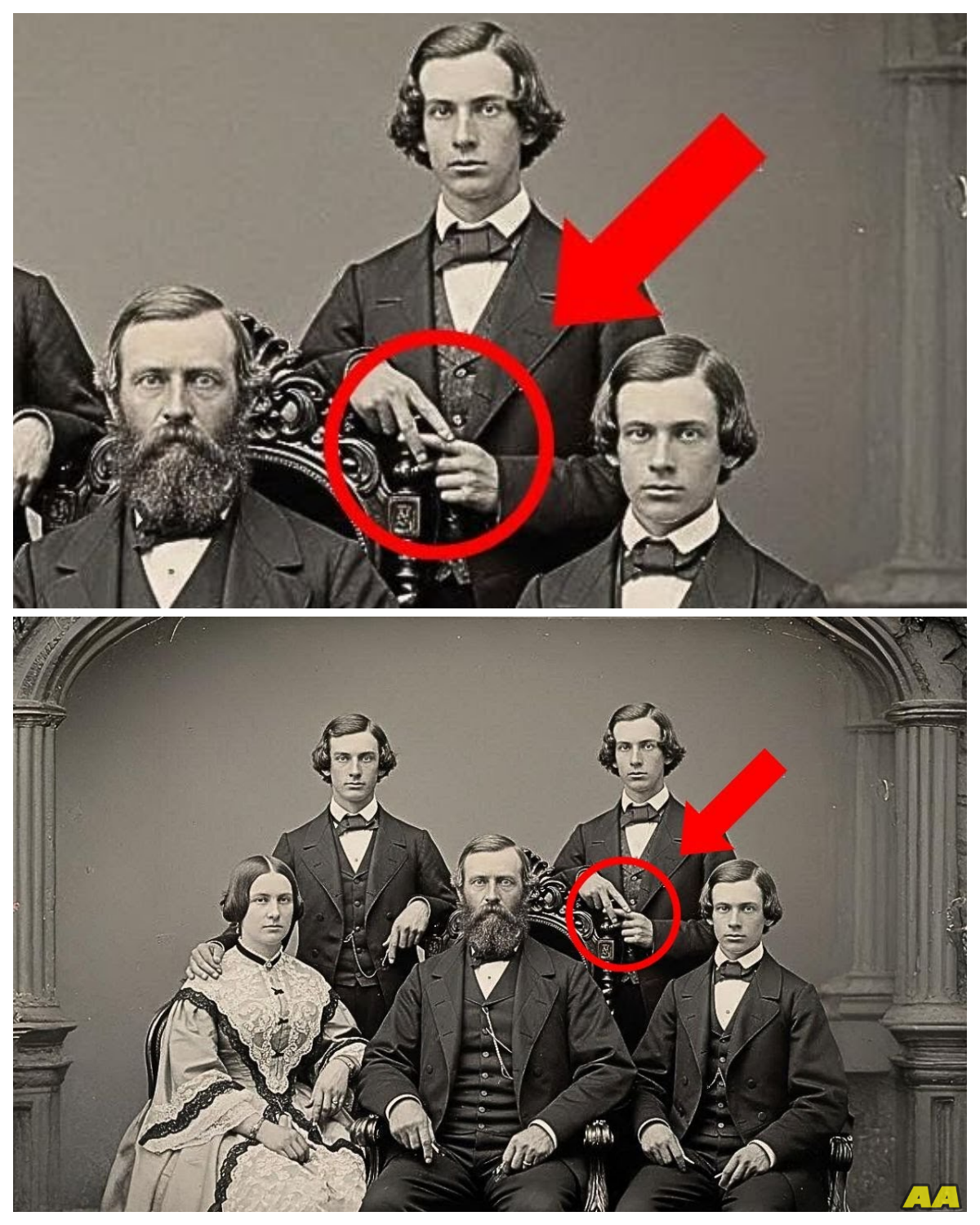

Then she noticed the hands.

In formal Victorian photography, hand placement was carefully choreographed.

Hands rested on furniture, clasped together or hung naturally at sides.

But something about this family’s hands seemed odd.

Sarah leaned closer, adjusting the magnification.

The father’s right hand, resting on the arm of his chair, had fingers positioned in an unusual configuration.

His index and middle fingers crossed while his thumb extended outward.

The mother’s hand on his shoulder mirrored a similar strange gesture.

Each of the three sons had their hands positioned differently, but all seemed deliberately posed in ways that violated typical photographic conventions.

Sarah felt her heart rate increase.

She’d seen hand positions like these before, not in photographs, but in historical documents about coded communication systems.

She grabbed her phone and pulled up her research files, scrolling through images of abolitionist signals and underground railroad codes.

Sarah’s hands trembled as she compared the photograph to her reference materials, the father’s crossed fingers.

That was a known abolitionist signal meaning safe passage.

The mother’s gesture, thumb and pinky extended while other fingers curled.

That indicated shelter available.

Each son’s hand position corresponded to different coded messages she’d seen documented in underground railroad communications.

But this made no sense.

Richmond, Virginia in 1860 was slave territory, a city where abolitionist sympathies could get you killed.

Why would a wealthy white family in the Confederate capital pose for a photograph displaying Underground Railroad codes? Sarah pulled up the donor information again.

The estate sale had been held in Philadelphia.

The photographs discovered in the attic of a house that had belonged to Harrison descendants.

She found a phone number and called immediately.

An elderly woman answered, “Hello, Mrs.

Patterson.

This is Dr.

Sarah Chen from the Virginia Museum of History.

I’m calling about the photographs your family donated.

Specifically, the Harrison family portrait from 1860.

Oh, yes.

Mrs.

Patterson said, “My great great-grandfather’s family.

I’m afraid I don’t know much about them.

They left Virginia during the war and never went back.

Do you know why they left?” There was a pause.

Family stories say they weren’t welcome in Richmond anymore.

Something about their sympathies being unpopular, but the details were never discussed.

My grandmother said there were things about the family that were better left buried.

Sarah felt electricity run through her.

Mrs.

Patterson, did anyone in your family ever mention underground railroad activities? The silence stretched longer this time.

Finally, Mrs.

Patterson spoke, her voice barely above a whisper.

How did you know? The photograph, Sarah said.

Their hands.

Each person is making coded signals used by abolitionists.

This wasn’t just a family portrait.

It was a message.

Mrs.

Patterson’s breath caught.

My grandmother told me once when she was very old and her memory was failing that our ancestors had been conductors.

I thought she was confused talking about railroad workers, but she said they conducted souls to freedom and it cost them everything.

I never understood what she meant.

Sarah explained what she’d discovered, describing each hand signal and its meaning.

As she spoke, she could hear Mrs.

Patterson crying softly.

All these years, the elderly woman said, “I thought we came from Confederate sympathizers.

My whole life I’ve carried shame about my Virginia roots, assuming my ancestors had been on the wrong side of history.

And now you’re telling me they were heroes.

” “If I’m right about this, yes,” Sarah said carefully.

“But I need to verify it.

” “Do you have any other family documents, letters, diaries, business records?” “There’s a trunk,” Mrs.

Patterson said, “in my basement full of old papers I’ve never gone through.

My mother said they were too fragile.

told me to leave them alone.

Would those help? They might contain everything we need.

Sarah said, “Would you be willing to let me examine them?” Two days later, Sarah stood in Mrs.

Patterson’s basement in a quiet Philadelphia suburb, staring at a leatherbound trunk that hadn’t been opened in decades.

The old woman hovered nearby, her weathered hands clasped together nervously.

“I haven’t looked inside since I was a child,” Mrs.

Patterson said.

“My mother caught me trying to open it once and got so upset.

She said the past should stay buried, that some family secrets were too dangerous to dig up.

I never understood what she meant.

Sarah carefully lifted the trunks lid.

Inside, wrapped in oil cloth, were stacks of documents, letters tied with ribbon, ledgers, journals, and loose papers.

She pulled out the first bundle gently, aware that the paper might disintegrate if handled roughly.

The top letter was dated April 1859, written in elegant script.

Sarah read aloud.

My dearest brother, I write to inform you that our mutual friends merchandise arrived safely.

23 pieces in total, all in acceptable condition despite the difficult journey.

They have been temporarily housed and will continue north as arranged.

Please send word when the next shipment is expected.

Mrs.

Patterson leaned forward.

Merchandise? What does that mean? It’s code, Sarah explained.

Underground railroad operators used business language to disguise their activities.

merchandise or packages meant escaped slaves.

Housed meant hidden in safe houses.

This letter is describing the successful transport of 23 escaped slaves through Richmond.

The elderly woman’s eyes widened through Richmond.

But that was the heart of slave territory.

Exactly.

Which made it brilliant.

Who would suspect a wealthy merchant family in the Confederate capital of running an underground railroad station? Sarah continued reading through the letters, finding message after coded message describing rescue operations, safe house locations, and coordination with other conductors.

One letter from October 1859 was more explicit.

Father grows increasingly concerned about discovery.

The neighbors question why our warehouse receives shipments at odd hours.

Thomas suggested we reduce operations, but mother insists we cannot abandon our principles simply because the risk has grown.

She says, “Each soul we save justifies whatever consequences we might face.

” Sarah looked up at Mrs.

Patterson.

“Thomas, would that be one of the sons in the photograph?” “Thomas Harrison was my great great-grandfather,” Mrs.

Patterson confirmed.

“He moved to Philadelphia in 1861 and never returned to Virginia.

The family story was that he’d had a falling out with his parents, but no one ever explained why.

” Sarah pulled out a journal next, its leather cover cracked with age.

The first entry was dated January 1858, written in the same hand as the photograph’s label, presumably the patriarch, the father in the family portrait.

She read the opening passage.

I have decided to keep this record, though I know the danger it represents.

If discovered, these words could condemn my entire family.

But I believe history must know what we attempted, whether we succeed or fail.

We are five people, myself, my beloved wife, Katherine, and our three sons.

And we have pledged ourselves to a cause that makes us traders to our neighbors and criminals under the law.

We will use our textile business as cover to transport escaped slaves through Richmond and north to freedom.

Um Sarah spent the next 6 hours carefully documenting the journal entries, her hands cramping from typing on her laptop as she transcribed the father’s detailed accounts.

The Harrison family’s operation had been extraordinarily sophisticated and breathtakingly dangerous.

The father, whose name was revealed as Robert Harrison, owned a textile import business with warehouses near Richmond’s docks.

He received shipments of fabric from northern states and distributed them throughout Virginia.

The business provided perfect cover.

Large wagons arriving and departing at all hours, warehouses with hidden storage spaces, regular travel routes that connected to other cities.

But Robert hadn’t started out as an abolitionist.

His journal revealed a gradual awakening that began in 1856 when he witnessed a slave auction that turned his stomach.

I watched a mother torn from her children sold to separate owners who dragged them in different directions while she screamed.

Her anguish was inhuman, or rather too human.

In that moment, I understood that what we call property are people who feel and suffer as deeply as my own beloved family.

I returned home and could not meet my wife’s eyes.

How could I claim to be a moral man while benefiting from a system built on such cruelty? Katherine Harrison, his wife, had apparently shared his revulsion.

Together, they’d made contact with Quaker abolitionists in Philadelphia, who connected them to the Underground Railroad network.

The challenge was logistics.

Richmond was deep in slave territory far from the free states.

Moving escaped slaves through the city required an elaborate system of concealment and misdirection.

Robert’s journal described how they’d modified their warehouse, creating false walls and hidden compartments in their shipping crates.

Escaped slaves would be smuggled into Richmond from surrounding plantations, hidden in the warehouse for a few days, then transported north in fabric shipments.

The shipments went to business contacts in Pennsylvania, who were also part of the network.

Our three sons have each taken on specific roles, Robert wrote in March 1858.

Thomas, our eldest at 28, manages the warehouse operations and coordinates with our northern contacts.

He has proven remarkably steady under pressure.

James, 24, serves as our lookout and messenger, moving through the city, gathering intelligence about slave catchers and suspicious officials.

And William, just 19, has taken the most dangerous role.

He travels to plantations, posing as a fabric buyer, making contact with enslaved people and arranging their escapes.

Sarah paused at that entry, stunned by the scale of risk.

William would have been younger than most of her graduate students, traveling alone into plantations where slave owners held absolute power, arranging escapes that could get him hanged if discovered.

She found a later entry from June 1859 that made her blood run cold.

William returned from a buying trip with bruises and a split lip.

He’d been questioned by a plantation overseer who suspected his true purpose.

William maintained his cover story barely.

He told me tonight that he fears he’s being watched.

I have advised him to suspend his activities, but he refuses.

Every week I wait, he said, is another week those people suffer in chains.

I won’t stop because I’m scared.

Mrs.

Patterson, who’d been reading over Sarah’s shoulder, wiped tears from her eyes.

They were just young men, boys, really, and they were doing this.

Sarah continued through the journal, searching for any mention of the photograph that had started this investigation.

She found it in an entry dated February 1860.

Catherine has conceived of a brilliant and terrifying idea.

She proposes we commission a family portrait, something we have avoided until now, fearing any permanent record of our faces.

But Catherine argues that we need a way to identify ourselves to other conductors and sympathizers without speaking openly.

She suggests we incorporate our hand signals into the photograph itself.

Anyone who understands the codes will recognize us immediately as allies.

To others, we will appear as merely another prosperous Richmond family.

The next entry from March 1860 described the photography session.

We visited Jay Morrison’s studio today and sat for our portrait.

The photographer found our hand positions unusual and tried several times to correct them, but I insisted on the arrangement.

Catherine placed her hand on my shoulder in the shelter position.

I kept my fingers in the safe passage formation.

Thomas signed northbound route.

James indicated supplies available, and William’s gesture meant multiple stations.

The photographer finally relented, though he muttered about unconventional compositions.

Sarah sat back, the full picture finally clear.

The photograph wasn’t just a family portrait.

It was an identification card, a credential that would prove the Harrison’s allegiance to any abolitionist who knew the codes.

They could show the image to potential allies without speaking dangerous words, letting the hand signals do the communicating.

But there was something else in Robert’s tone, something that suggested deeper purpose.

She read ahead to an entry from later that same month.

I have ordered five copies of the photograph, though the expense is considerable.

Catherine understands my reasoning without my having to explain.

If we are discovered, when we are discovered, for I harbor no illusions about our ability to continue indefinitely, this photograph will be our legacy.

Proof that we existed, that we resisted, that we chose our principles over our safety.

Future generations should know that not all white southerners were complicit in the evil of slavery.

Mrs.

Patterson’s voice was thick with emotion.

He knew they would be caught.

He suspected it was inevitable, Sarah said.

Operating in Richmond, the Confederate capital for years, the odds were against them.

She flipped forward, looking for 1861 entries, but found something unexpected.

The journal ended abruptly in December 1860.

The final entry was dated December 20th, 1860, the day South Carolina seceded from the Union.

War is coming.

We all feel it in the air, thick as smoke.

South Carolina has left the Union, and Virginia will surely follow.

Our operations have become infinitely more dangerous.

We are no longer just breaking the law.

We will soon be enemies of a new nation.

Katherine and I discussed closing our network.

But how can we abandon people to slavery when their need is greatest? We have agreed to continue as long as we are able.

God grant us courage for what lies ahead.

Then nothing.

No more entries.

Sarah flipped through the remaining blank pages, but Robert had stopped writing.

“What happened to them?” Mrs.

Patterson asked.

“Why did the journal stop?” Sarah returned to the trunk, searching through the remaining documents.

She found business ledgers, receipts, correspondents, but nothing personal after December 1860.

Then at the bottom of the trunk, she discovered a small wooden box.

Inside the wooden box were letters, different from the earlier business correspondents.

These were personal, intimate, written in various hands.

Sarah recognized Katherine Harrison’s elegant script on several.

She opened the first letter dated January 1861.

My dearest sister in Philadelphia, I write with news, both encouraging and terrible.

Our network has successfully moved 42 souls to freedom this month alone.

Desperation drives more attempts as people realize war will only make escape more difficult.

But Robert grows gaunt with worry.

He no longer sleeps properly.

Yesterday I found him standing at the warehouse window at dawn just staring at the street.

He believes we are being watched.

Sarah opened the next letter from March 1861.

Virginia has secceeded.

Richmond is now capital of the Confederate States.

Neighbors who were merely suspicious have become openly hostile.

Someone painted traitor on our warehouse wall last night.

Robert wants to send the boys north, but Thomas refuses to leave.

He says, “If we abandon our work now, when people need us most, everything we’ve risked means nothing.

My heart breaks with pride and terror in equal measure.

” Another letter dated July 1861 was harder to read.

The ink smudged in places as if water or tears had fallen on the paper.

They know.

I don’t know how, but they know.

Men came to the house yesterday demanding to search the warehouse.

Robert showed them around, maintaining calm, while my heart thundered so loudly, I feared they’d hear it.

We had three people hidden in the false wall compartment.

The men searched for 2 hours.

They found nothing, but they promised to return.

Robert says, “We must evacuate immediately.

Get our people out tonight and close operations.

” Sarah’s hands were shaking as she opened the next letter.

It was dated August 1861 and written in Thomas’s hand, addressed to relatives in Philadelphia.

I write with devastating news.

Father has been arrested on charges of aiding escaped slaves.

Mother tried to intervene and was also taken into custody.

James, William, and I barely escaped.

We are heading north tonight with the last group of people we were sheltering.

17 souls total.

We cannot return to Richmond.

Everything we built is lost.

Mrs.

Patterson gasped.

They were arrested, both of them.

Sarah nodded, continuing to read Thomas’ letter.

The trial, if it can be called such, lasted less than a day.

Father and mother were convicted of treason against the Confederacy.

Father was sentenced to 15 years hard labor, mother to 10 years.

The judge said their sentences were lenient only because of father’s previously respected position in the community.

They were given 48 hours to settle their affairs before being transported to prison.

The next document was a legal record, conviction papers for Robert and Katherine Harrison, dated August 15th, 1861.

The charges were detailed, aiding escaped slaves, conspiracy against the Confederate States operating an unlawful network.

The evidence included testimony from neighbors, documentation of suspicious warehouse activities, and statements from captured escaped slaves who’d been forced to reveal their helpers.

Sarah found one more letter in the box, this one in Catherine’s hand, written from prison in September 1861.

My beloved sons, by the time you read this, your father and I will be beginning our sentences.

Do not grief for us.

We made our choice with full knowledge of potential consequences.

We have no regrets.

Every person we helped to freedom was worth whatever price we must now pay.

You must live your lives forward, not looking back.

Build families.

Pursue happiness.

Never be ashamed of what we did.

We loved you enough to risk everything for a principle.

We hope you will understand.

The letter continued.

I have one request.

Keep the photograph.

Show it to your children and grandchildren.

Tell them that ordinary people, merchants, mothers, sons, can resist extraordinary evil.

Tell them we chose courage over comfort, principle over prosperity.

And tell them that in the darkness of history’s worst moments, there were always people who lit candles of resistance.

Sarah knew she needed to find out what happened to Robert and Katherine Harrison after their conviction.

She contacted the Library of Virginia’s archives and requested any available prison records from Confederate facilities operating during the Civil War.

3 days later, she received digital scans of documents from Castle Thunder, a notorious Confederate prison in Richmond where political prisoners and accused traitors had been held.

Among the thousands of entries, she found the Harrison’s Robert Harrison admitted August 17th, 1861.

Prisoner number 347, convicted traitor.

Sentence 15 years hard labor.

Medical notes documented his deteriorating health through the war years.

Malnutrition, exhaustion, illness.

Then in March 1863, a final entry, prisoner Da 347, deceased.

Cause: pneumonia complicated by malnutrition and poor conditions.

Body released to family.

Katherine Harrison, admitted August 17th, 1861.

Prisoner number 428.

Convicted traitor.

Sentence 10 years hard labor.

Her medical records showed similar decline, but she’d survived longer.

The final entry came in April 1865, just days after the war ended.

Prisoner number 428 released following Confederate surrender.

Physical condition poor.

Transported to Philadelphia by family members.

Sarah felt tears streaming down her face.

Robert had died in prison, never living to see the Union victory or the abolition of slavery.

Catherine had barely survived, freed only when the Confederacy collapsed.

She called Mrs.

Patterson immediately.

I found prison records.

Your great great great-grandfather died in Castle Thunder in 1863.

Catherine survived but was imprisoned until the war ended.

The elderly woman was silent for a long moment.

Did Catherine did she recover? I don’t know yet, Sarah admitted.

The records just say she was transported to Philadelphia.

Let me search for Philadelphia death records from 1865 onward.

She spent the next several hours combing through databases.

Finally, she found Katherine Harrison’s death certificate.

December 1866, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

cause of death, complications from imprisonment, general dability.

She’d survived just 18 months after her release, her health permanently destroyed by four years of hard labor and poor conditions.

But Sarah also found something else.

Catherine’s obituary in a Philadelphia abolitionist newspaper.

It was longer than typical obituaries, clearly written by someone who’d known her story.

Katherine Harrison, formerly of Richmond, Virginia, passed into rest on December 14th.

Mrs.

Harrison was a heroine of the Underground Railroad, operating a station in the Confederate capital itself at tremendous personal risk.

She and her husband Robert, deceased 1863, saved an estimated 200 enslaved persons, providing them shelter and passage to freedom.

Their courage cost them everything, their business, their home, their freedom, and ultimately their lives.

Mrs.

Harrison is survived by three sons, Thomas, James, and William, all of Philadelphia, and by the countless individuals whose lives she forever changed.

Let her sacrifice never be forgotten.

200 people.

Sarah sat back, overwhelmed by the scale of what the Harrison family had accomplished.

For three years, in the most dangerous possible location, they’d operated a rescue network that saved 200 human beings from slavery.

She called Mrs.

Patterson again and read the obituary aloud.

The elderly woman wept openly.

200 people, Mrs.

Patterson whispered, “My ancestors saved 200 people, and I never knew.

My whole life I never knew.

” Sarah returned to the trunk, searching for any documents from Thomas, James, or William after the war.

She found a cache of letters written in the 1870s and 1880s after the war had ended and the reconstruction period was underway.

Thomas had become a textile merchant in Philadelphia, continuing his father’s legitimate business.

His letter showed a man haunted by survivors guilt.

I think often of father dying in that prison while I lived free in the north.

He saved my life by insisting we flee.

But I wonder if I should have stayed and faced arrest alongside him.

Mother told me before she died that father’s last words to her were about us.

He made her promise to ensure we understood that our escape had given their sacrifice meaning.

200 people freed, he said.

And our son’s alive to tell the story.

I try to believe that was enough.

James had become a teacher dedicating his life to educating formerly enslaved people.

One letter from 1873 described his work.

I teach reading and writing to men and women who were kept deliberately ignorant by slavery.

Some are elderly, their fingers stiff with arthritis as they learn to hold a pen for the first time.

Others are children whose parents were freed too late to be educated themselves.

When they master a new word, I think of father and mother and all they sacrifice to break the chains.

Education is my way of continuing their work.

William’s path had been different.

He’d become a vocal abolitionist speaker, traveling throughout the North giving speeches about his family’s underground railroad activities.

Sarah found printed copies of several speeches he delivered in the 1870s and 1880s.

One speech delivered in Boston in 1875 described the family photograph.

I was 19 years old when we sat for that portrait.

My father insisted we hold our hands in specific positions, signals that abolitionists would recognize.

At the time, I thought it was mere bravado.

Now I understand it was testimony.

My father knew our work might cost us everything.

He wanted proof that we’d existed, that we’d chosen the right side of history.

The photograph was his way of saying we were here.

We resisted.

We did what was right, even when it was dangerous.

Another speech from 1882 went further.

People ask me if my parents’ sacrifice was worth it.

They died for their principles, spent their final years in prison, lost everything they’d built.

Was it worth it? I tell them to ask the 200 people my family helped to freedom.

Ask the children and grandchildren of those 200 people who live free because my parents risked everything.

Ask the man who became a minister, the woman who became a teacher, the families who built lives in freedom because someone was brave enough to help them escape slavery.

Yes, it was worth it.

A thousand times over, it was worth it.

Sarah found one final document that made her catch her breath.

A ledger William had kept, attempting to track down every person his family had helped.

It contained names, dates of passage through the Richmond Station, and any information he’d been able to gather about their subsequent lives.

The ledger showed William had spent decades trying to find these people, documenting their stories.

Some entries were simple.

Martha transported July 1859, believed to have reached Canada.

Others were detailed.

Samuel and his wife Rose transported December 1860 with three children.

Samuel became a carpenter in Philadelphia.

Children attended school, family thriving.

At the end of the ledger, William had written a summary.

Of the approximately 200 souls my family helped, I have been able to trace 73.

All are living in freedom.

Many have families.

Their children attend school.

They own property, operate businesses, participate in civic life.

This is my parents legacy, not their suffering, but the lives they saved and the freedom they made possible.

Sarah spent three months preparing an exhibition about the Harrison family.

The Virginia Museum of History devoted an entire gallery to their story with the 1860 photograph as the centerpiece.

Around it, she arranged the documents she’d discovered.

Robert’s journal, the coded letters, Catherine’s final message to her sons, the prison records, William’s speeches and ledger.

The exhibition opened on a humid Virginia evening.

Sarah had invited Mrs.

Patterson and asked her to bring as many family members as possible.

She’d also spent weeks tracking down descendants of people the Harrison family had helped, names from Williams ledger that she could connect to living relatives through genealological research.

The gallery filled with over a hundred people.

Mrs.

Patterson arrived with her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, four generations of Harrison descendants.

They stood before the photograph, studying the faces of ancestors they’d never known about.

But Sarah’s most powerful moment came when she introduced Mrs.

Patterson to Marcus Johnson, an elderly black man from Philadelphia.

Marcus held a worn photograph of his own, his great great-grandfather, Samuel.

The same Samuel mentioned in Williams Ledger.

“Your family saved my ancestor,” Marcus said, his voice breaking.

“Samuel and Rose and their three children, December 1860.

” “They escaped from a plantation in Virginia, made it to Richmond, and your family hid them in a warehouse, and transported them north, hidden in fabric shipments.

” Mrs.

Patterson clasped his hands, both of them crying.

“I didn’t know,” she whispered.

“I lived my whole life not knowing what my family had done.

” Well, now you know, Marcus said, “And now I can thank you.

” My great great-grandfather became a carpenter.

He built a life in freedom.

He had six children.

Those six had children of their own.

Today, there are over 60 people in my family tree.

All of us alive because your ancestors risked everything to help slaves they’d never met.

Sarah watched as more descendants met each other.

Harrison family members connecting with the descendants of people their ancestors had saved.

The gallery filled with tears and embraces with stories shared and gaps in family histories finally filled.

During her speech opening the exhibition, Sarah addressed the crowd.

This photograph was taken in March 1860, one year before the Civil War began.

Five members of the Harrison family, Robert, Catherine, Thomas, James, and William posed for this portrait with their hands positioned in coded signals.

To casual observers, it was just another family photograph.

But to abolitionists who knew the codes, it was a message.

Here is a safe house.

Here is shelter.

Here is passage north.

She paused, looking at the image projected behind her.

What makes this photograph extraordinary isn’t just the coded signals.

It’s what happened after.

6 months after this photograph was taken, Virginia seceded from the Union.

Richmond became the Confederate capital.

The Harrison family could have stopped their underground railroad operations.

They could have protected themselves.

Instead, they continued their work in the most dangerous possible environment, and they paid a terrible price.

Sarah described Robert’s death in prison, Catherine’s years of hard labor, the sons escaped north with the last group of people they were sheltering.

But here’s what matters most.

They saved approximately 200 people from slavery.

200 human beings who lived free because this family chose courage over safety.

She gestured to the descendants in the audience.

In this room tonight are Harrison family members who never knew this history and descendants of the people they saved who never knew who helped their ancestors.

This photograph, this image that’s been sitting in archives for over a century and a half has finally brought you together.

The exhibition ran for six months and became the most visited display in the museum’s history.

News coverage spread nationally, and scholars began researching other possible coded photographs from the Civil War era.

Sarah received dozens of messages from people asking her to examine family photographs for similar signals.

But the most meaningful impact was personal.

Mrs.

Patterson created a family history website documenting everything Sarah had discovered and sharing it with her extended family.

Harrison descendants from across the country reached out, many of them shocked to learn about their ancestors abolitionist activities.

I grew up in Virginia.

One distant cousin wrote, “I was always told we had to leave the state because of some family scandal.

I assumed it meant we’d been Confederate sympathizers who’d done something shameful.

” Learning the truth that we left because we were abolitionists who got caught helping escaped slaves has completely changed how I understand my family and myself.

Marcus Johnson organized a gathering of descendants from the people the Harrison family had helped.

Sarah attended the event in Philadelphia held in a church not far from where Thomas, James, and William had settled after fleeing Richmond.

Over 200 people came, descendants of Samuel and Rose, of Martha who’d gone to Canada, of dozens of others whose names appeared in William’s ledger.

They shared stories that had been passed down through generations.

One woman described how her great great-randmother had told her grandchildren about the white family in Richmond who hid us in their warehouse and saved our lives.

Another man brought a quilt his ancestor had made in freedom, incorporating a pattern that resembled the fabric the Harrison family had imported, a deliberate memorial to the people who’d helped her escape.

Sarah stood before the photograph one last time before the exhibition closed.

She’d spent months studying every detail.

The studio backdrop, the Victorian clothing, the serious expressions.

But now she saw it differently.

She saw five people making the conscious choice to create evidence of their resistance.

Robert, and Catherine, knowing they might not survive, but determined to leave proof of their principles.

Thomas, James, and William, young men who could have protected themselves by doing nothing but instead risked everything.

The hand signals weren’t just codes.

They were declarations.

Quiet acts of defiance captured in silver and glass, preserved through time, waiting to tell their story to anyone who learned to read the language.

Mrs.

Patterson stood beside her.

At 83 years old, she’d spent the past 6 months learning everything she could about her ancestors.

“Sarah,” she said quietly, “I’ve been thinking about what Catherine wrote in her letter from prison, about how ordinary people can resist extraordinary evil, about lighting candles in the darkness.

” “It’s a powerful metaphor,” Sarah agreed.

It’s not a metaphor, Mrs.

Patterson said.

It’s a challenge.

She wasn’t just talking about herself.

She was talking about every generation that comes after, asking us, “When you face injustice, what will you do? When doing the right thing is dangerous, will you stay silent or will you resist?” Sarah looked at the photograph again.

Those five serious faces, those deliberately positioned hands.

What do you think they’d want us to know, Mrs.

Patterson smiled, tears in her eyes? I think they’d want us to know that we’re capable of more courage than we imagine.

That ordinary people, merchants, teachers, students, parents have the power to change history, that taking a stand costs something.

Sometimes everything, but the cost of staying silent is higher.

She gestured to the exhibition materials around them.

This photograph sat in an archive for 150 years.

All that time, their story was hidden, waiting.

Now it’s out in the world again.

And look what happened.

Families reunited.

History corrected.

people understanding that resistance has always existed, even in the darkest places.

Sarah nodded.

Your family story is going into textbooks.

Mrs.

Patterson, students will learn about the Harrison family, about underground railroad operations in Confederate territory, about white allies who paid the ultimate price for their principles.

Good, Mrs.

Patterson said firmly.

Because we need those stories.

We need to know that people have always fought back against injustice, even when it seemed hopeless, especially when it seemed hopeless.

The photograph would be permanently installed in the museum’s Civil War Gallery.

Sarah had been told future visitors would see Robert, Katherine Thomas, James, and William Harrison frozen in their 1860 portrait, hands positioned in coded signals that once meant safety, shelter, passage to freedom.

But the photograph was more than historical artifact now.

It had become a mirror, reflecting questions back at everyone who viewed it.

What would you risk for your principles? What cost are you willing to pay to resist injustice? When doing the right thing is dangerous, what will you choose? Five people in a Richmond photography studio in 1860 had answered those questions with their hands, their lives, their sacrifice.

Their message, encoded in gesture and preserved in silver, had finally been read and understood.

And it would continue speaking to future generations, a permanent testament to the power of ordinary people who refused to accept evil no matter the cost.

The exhibition closed, but the story lived on in textbooks and classrooms, in family gatherings, and genealological research.

In every conversation about courage and resistance and the choices we make when history demands we choose a side.

The Harrison family photograph, once just another forgotten image in an archive, had become something more.

Evidence that resistance has always existed.

Proof that ordinary people can be extraordinary.

And a reminder that the decisions we make echo through generations.

News

⚖️Colorado’s long-unsolved 1992 and 1998 cases reach a jaw-dropping conclusion as arrests are made, igniting panic, whispered accusations, and reopened wounds across a community that thought the past had settled — Delivered with theatrical intensity, the moment is less about closure and more about reckoning, as decades of quiet deception crumble under one devastating revelation👇

The Shadows of Silence: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of rural Colorado, where the mountains loom…

🕰️Michigan’s 1993 cold case finally unravels decades of silence as a shocking arrest rattles a community that thought the past was safely buried, exposing secrets, lies, and betrayals that many assumed were long forgotten — In a narrator’s tense, biting tone, neighbors whisper in disbelief, old friends exchange suspicious glances, and the quiet streets are suddenly haunted by the truth that justice sometimes waits decades to strike👇

Shadows of the Past In the heart of a snow-covered Michigan town, Hilary Evans was just a girl with dreams,…

🕰️Minnesota’s 1973 cold case erupts back into the spotlight as a decades-old murder is finally solved, leaving a tight-knit community reeling in disbelief, whispers of secrets long buried, and neighbors questioning everything they thought they knew about their friends, family, and the quiet streets they call home — In a narrator’s biting, suspenseful tone, the arrest lands like a thunderclap, turning memories into evidence and showing how the past never truly lets go👇

Echoes of Silence: The Carvalho Twins’ Haunting Legacy In the summer of 1973, Michael and Daniel Carvalho, sixteen-year-old twins, vanished…

End of content

No more pages to load