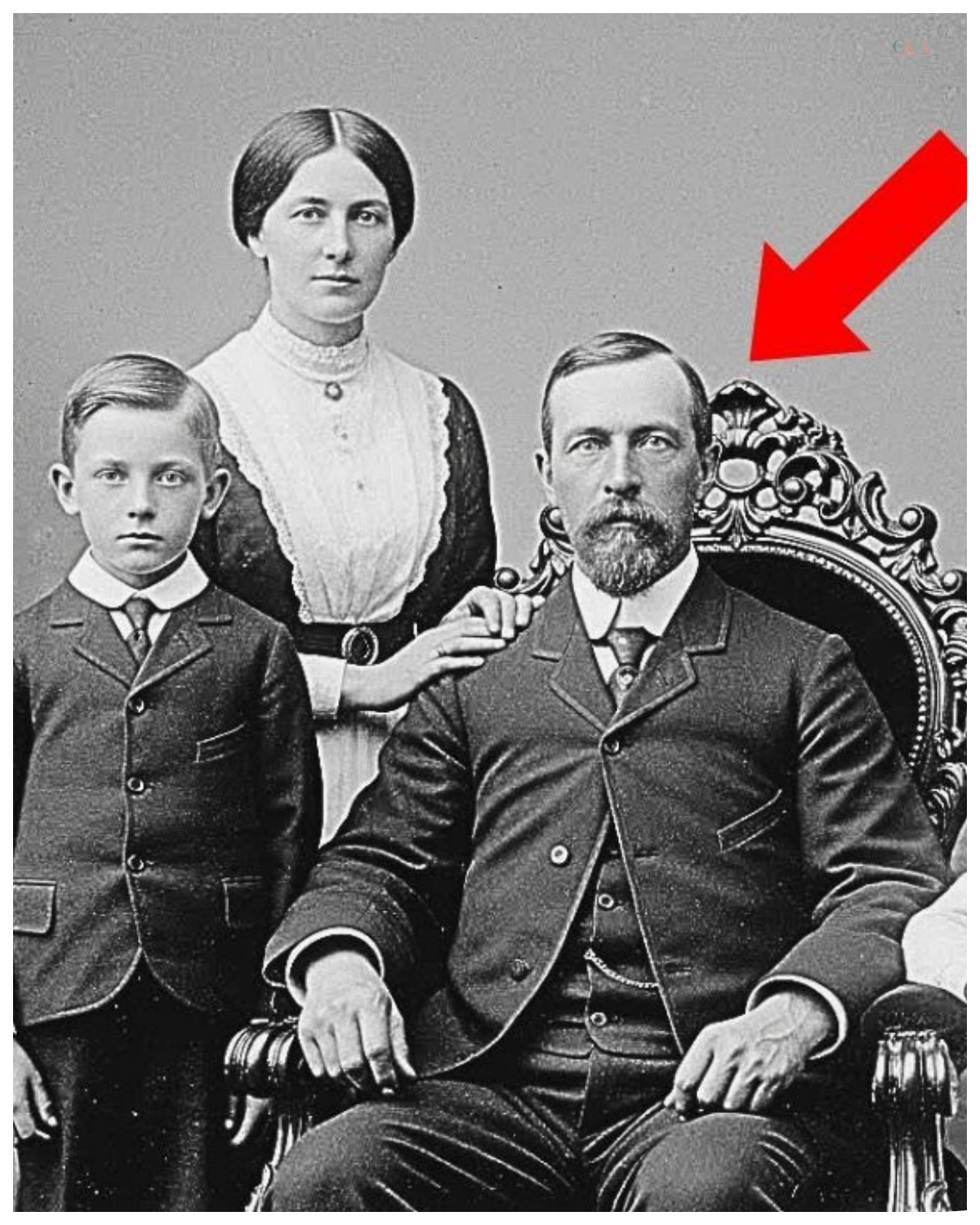

Why were historians pale when enlarging this 1901 family studio photo? Dr.Elizabeth Carter scrolled through another batch of digitized photographs on her computer screen.

The November afternoon felt quiet in the University of Pennsylvania archives office, the only sound, the gentle hum of her computer.

As a historian specializing in early 20th century immigration, she had examined thousands of similar images, formal studio portraits of immigrant families, carefully posed and stiffly dignified.

This particular collection came from a Philadelphia photography studio that had operated from 1887 until 2003.

The owners had preserved decades of glass plate negatives, and Elizabeth’s team was digitizing them for a project documenting the city’s German immigrant community.

The photograph on her screen seemed unremarkable.

Dated March 1901, it showed a family of five in typical formal arrangement.

A stern father seated in an ornate chair, his wife standing beside him with her hand on his shoulder, three children arranged around them.

The father wore a dark suit with a high starched collar.

The mother’s dress was simple but carefully maintained.

The children, two boys and a girl, ages perhaps 4 to nine, stood motionless in Sunday clothes, faces solemn.

Elizabeth made notes about the composition and moved to save it when something made her pause.

She zoomed in on the father’s face, studying his expression.

There was tension in his eyes, a guardedness that seemed different from typical studio portrait stoicism.

Her colleague, Dr.

Marcus Webb, knocked on her door.

Marcus specialized in forensic historical analysis and had been helping with the digitization project using advanced imaging technology to restore and enhance damaged photographs.

Elizabeth, do you have a minute? He asked.

I’ve been running portraits through the new ultra highresolution scanner we got last month.

The detail it pulls from these old images is remarkable.

We’re seeing things invisible to the naked eye, even when photos were first taken.

Elizabeth gestured to her screen.

I was just looking at one from 1901.

Family portrait.

Pretty standard, but something about the father’s expression caught my attention.

Marcus studied the image with professional interest.

Mind if I run this through the enhancement process? Sometimes studio portraits reveal fascinating details at higher resolution.

Fabric patterns, jewelry, even text on documents people were holding.

Go ahead, Elizabeth replied, sending him the file.

3 days later, Marcus returned looking unsettled, almost shaken.

Without a word, he pulled up a chair and opened his laptop.

Elizabeth,” he said quietly, “you need to see what I found in that photograph.

” The image on Marcus’ laptop was the same family portrait, but now processed through multiple enhancement layers.

“The resolution was extraordinary.

” Elizabeth could see individual fabric threads, wooden chair grain, even subtle photographic paper texture.

Marcus navigated to the father’s neck area and zoomed in above the starched collar.

“Look here,” he said tensely.

“The studio lighting and high collar almost completely hide it, but when we enhance contrast and adjust shadows, it becomes visible.

Elizabeth leaned forward, eyes narrowing.

There, on the left side of the man’s neck, partially concealed by the collar, but unmistakable in the enhanced image, was a scar, not a small mark from accident or minor injury, a long, irregular line running from below his ear toward his collarbone.

The kind of scar that told a story of violence and survival.

“My God,” Elizabeth whispered.

“That’s not surgical or accidental.

That looks like a knife wound,” Marcus finished grimly.

“Deep, probably life-threatening when it happened.

See the irregular line suggests struggle or multiple cuts.

And look, there are actually two scars running parallel, very close together.

Someone tried to kill this man.

Elizabeth studied the enhanced image carefully.

Scars weren’t unusual in photographs from this era.

Industrial accidents, street fights, rough living conditions left marks on many people, but this scar was different.

It had clearly been deliberately hidden.

The man had positioned his collar carefully, tilted his head slightly to minimize visibility, and the photographer had arranged lighting to cast concealing shadows.

“He didn’t want anyone to see this,” Elizabeth said slowly.

“Look at his positioning.

That’s not random.

” He knew the scar was there and actively tried hiding it.

Marcus nodded.

“That troubles me.

In 1901, photography was expensive and formal.

Families saved months to afford studio portraits like this.

They wore best clothes, presented most respectable image.

But this man is hiding evidence of extreme violence.

Why? Elizabeth pulled up research files on the digitization project.

Each photograph had been cataloged with whatever information the studio preserved.

Names, dates, addresses when available.

She found the entry.

Studio records list them as the Vagner family.

She read aloud.

Father, Friedrich Vagner, age 34.

Mother, Anna Vagner, age 31.

Children, Wilhelm, 8.

Otto, 6.

Margaret 4.

Address 1247 North Second Street, Philadelphia.

Photograph taken March 19th, 1901.

They paid $2.

Any other records on this family? Marcus asked.

Elizabeth was already accessing genealological databases.

Let me check.

Elizabeth found Friedrich Vagner listed in the 1900 Philadelphia city directory at the North Second Street address.

His occupation, factory worker, likely one of the textile mills employing thousands of German immigrants.

The 1900 census confirmed the family composition and showed Friedrich and Anna had both immigrated from Germany in 1895.

But as Elizabeth searched further, something strange emerged.

Friedrich Vagner appeared in Philadelphia records beginning in 1896.

Before that, nothing.

No immigration records under that name arriving in 1895.

No records in New York or Baltimore where most German immigrants first landed.

No traceable family history back to Germany.

It’s like he appeared from nowhere in 1896,” she said, frowning.

Marcus leaned closer.

“What about the wife?” Elizabeth searched for Anna’s maiden name in marriage records.

She found it quickly.

Anna Schiller, married to Friedri Vagner in February 1896 at St.

Michael’s Lutheran Church.

She traced Anna’s records back and found complete immigration documentation.

Arrived New York in 1893 with her parents.

Clear family history before and after.

Anna’s history is complete and traceable, Elizabeth said.

But Friedri’s starts abruptly in 1896, the same year they married.

No prior records under that name.

The historians looked at each other, implications settling like a weight.

A man with no traceable history before 1896.

A carefully hidden scar from extreme violence and a formal family portrait designed to present respectability while concealing something darker.

We need to find out who Friedrich Vagner really was, Marcus said quietly.

and what happened to leave that scar.

Elizabeth spent the following week searching archives for any trace of Friedrich Vagner before his 1896 Philadelphia appearance.

She examined immigration records at the National Archives, studying passenger manifests from German ports between 1893 and 1896.

The name Friedri Vagner appeared dozens of times, one of the most common German names, but none matched the age, timing, or destination connecting to the photographed man.

She expanded her search to Baltimore, Boston, New Orleans.

Still nothing conclusive.

Friedrich Vagner had materialized in Philadelphia with no past, no paper trail, no connection to the extensive immigration bureaucracy, typically documenting every arrival.

Meanwhile, Marcus took a different approach.

He sent the enhanced scar image to Dr.

Patricia Hoffman at Johns Hopkins University, a medical historian specializing in historical wound patterns and forensic analysis of injuries in old photographs.

Her response came Thursday morning.

Subject line analysis of neck scarring.

Disturbing findings.

The report was clinical and detailed.

Scarring shows characteristics consistent with two deep lacerations inflicted by sharp blade likely four to 6 in knife.

Parallel wounds suggest either two quick successive attacks or single attack with two deliberate cuts.

Depth and location indicate life-threatening wounds likely severing or damaging left external jugular vein.

Survival required immediate medical intervention.

Healing pattern suggests injury occurred 3 to 5 years before photograph placing incident between 1896 and 1898.

Most significantly angle and pattern highly consistent with defensive injuries during assault.

Not self-inflicted, not accidental.

Elizabeth read Dr.

Hoffman’s report twice, her unease growing.

Friedrich Vagner had nearly been killed in a violent attack sometime around when he first appeared in Philadelphia records.

The timing couldn’t be coincidental.

She decided to approach the mystery differently.

If Friedrich Vagner wasn’t the man’s real name, perhaps there were records of missing persons, wanted criminals, or violent incidents from the mid 1890s matching his description and injury nature.

The Philadelphia Police Department’s historical archives were housed in the municipal building.

Elizabeth spent two days there examining ledgers of criminal cases, missing person’s reports, and incident records from 1894 to 1898.

The work was tedious.

Handwritten entries in fading ink, organized by date rather than name or crime type.

On the second afternoon, she found something that stopped her breathing.

A case file from New York City forwarded to Philadelphia police in October 1897 as routine information exchange between departments.

The file described a wanted man named Hinrich Bowman, age approximately 30 to 32, German immigrant, wanted for attempted murder in New York City in May 1897.

The description was general, brown hair, medium height, approximately 170 lb, details matching thousands of men.

But then Elizabeth read the crucial line.

Distinctive marking.

Victim reported inflicting defensive wounds on suspect’s neck and face during struggle.

Suspect believed seriously injured and may have sought medical treatment.

Her hands trembled photographing the document.

Hinrich Bowman had been wounded in the neck during the same time frame when Friedri Vagner received his scars.

The name was different, but the circumstance was too specific to ignore.

She continued through the file and found more details.

The attempted murder occurred at a boarding house in lower Manhattan.

Hinrich Bowman had lived there approximately two years when, according to witness statements, he attacked another resident, Yseph Kger, during an argument over money.

The attack was brutal.

Bowman attempted strangling Kger, then tried stabbing him when that failed.

Kger fought back, wounding Bowman severely before neighbors intervened.

Kger survived.

Bowman fled, bleeding heavily, and disappeared.

Police searched hospitals and clinics, but never found him.

The case remained open, but inactive.

Another violent crime in a city full of them.

Another suspect vanished into immigrant neighborhood anonymity and false names.

Elizabeth sat staring at the century old document.

Dark puzzle pieces fitting together.

A violent man named Hinrich Bowman, wounded in the neck in May 1897, disappears from New York.

Months later, a man named Friedri Vagner appears in Philadelphia with no prior history, marries quickly, starts a family, and hides a neck scar in every photograph.

It seemed almost impossible, but the evidence was there, waiting for confirmation.

Elizabeth returned to the university and shared her findings with Marcus.

They spread documents across her desk, the enhanced photograph, Dr.

Hoffman’s analysis, the New York police file, Philadelphia city records, and began cross-referencing every detail.

If Friedrich Vagner is actually Heinrich Bowman, Marcus said thoughtfully.

Then he changed identity sometime between May and late 1897, moved to Philadelphia, and built an entirely new life.

But why Philadelphia specifically? Elizabeth had been considering the same question.

Philadelphia was close enough to reach quickly if injured and desperate, but far enough he wouldn’t encounter anyone who knew him.

The German immigrant community here was large and insular.

He could blend easily, find factory work without too many questions, and no one would question another German worker with a common name.

She pulled up the 1896 marriage record again.

Look, he married Anna just 9 months after disappearing from New York.

That’s remarkably fast.

Most immigrant men waited years to marry, saving money and establishing themselves first.

But Bowman needed legitimacy, needed to look settled and respectable quickly.

Marcus nodded slowly.

And Anna, do you think she knew? It was the troubling question.

Elizabeth looked at the family photograph, studying Anna’s face, the hand resting on her husband’s shoulder, the careful expression, three children standing around them.

Did this woman know she had married a wanted man? Or had she been deceived like everyone else? I don’t know, Elizabeth admitted.

But we need to find what happened to this family.

The photograph was taken March 1901, four years after Bowman fled New York.

Did he live peacefully under his false identity? Or did his past catch up? She traced the Wagner family forward from 1901 rather than backward.

The 1901 directory listed them at the same North Second Street address.

The 1902 directory showed the same, but in 1903 there was a change.

The address listed Anna Vagner, widow, with three children.

Friedrich Vagner had died or disappeared between 1902 and 1903.

Elizabeth’s pulse quickened.

She searched death records for Philadelphia in those years and found it.

Friedri Vagner died April 7th, 1902, age 36.

Cause of death, homicide, stabbing.

The irony was almost unbearable.

The man who fled New York after attempting murder, who hid under false identity for 5 years, was himself murdered in the same violent manner he’d once employed.

“Where did it happen?” Marcus asked, reading over her shoulder.

Elizabeth pulled up the police incident report.

Brief and matter of fact, Friedrich Vagner, factory worker, found stabbed to death in an alley near his workplace evening of April 7th, 1902.

Murder weapon not recovered.

No witnesses.

Case investigated but never solved.

Elizabeth noticed something in the police report supplementary notes added a week after the murder.

A detective had written, “Victim’s wife questioned.

States’s husband had no known enemies.

Claims he was quiet, hardworking man.

However, neighbor reported hearing argument at Vagner residence 3 days before murder.

male voice, not vagnar’s heard shouting, “I found you, and you thought you could hide.

Wife denies knowledge of any visitor.

” Elizabeth and Marcus stared at the words.

Someone had found Hinrich Bowman.

After 5 years of hiding, someone from his past, perhaps connected to the attempted murder in New York, perhaps a victim seeking revenge, had tracked him to Philadelphia.

“Uh, the neighbor heard, “I found you,” Marcus said quietly.

Someone knew who he really was.

Three days later, Friedrich Vagner, Hinrich Bowman, was dead.

To understand who might have killed Bowman in 1902, Elizabeth needed to learn more about his 1897 victim.

Yseph Kger, the man Bowman had tried to murder in New York.

She returned to the New York police file and found additional details initially overlooked.

Joseph Kger had been 38 at the time of attack, also a German immigrant working as a skilled carpenter in Manhattan.

The police report included Kriger’s own witness statement given from his hospital bed 2 days after the assault.

His account was chilling in detail.

According to Kger, he and Bowman had lived in the same boarding house approximately 18 months.

Bowman had initially seemed friendly enough, quiet, and hardworking, employed at a nearby brewery.

But over time, Kger noticed disturbing behaviors.

Bowman drank heavily and became aggressive, showed no remorse discussing violence, had a volatile temper erupting without warning.

The argument that led to the attack started over trivial matter.

Bowman had borrowed $3 from Kriger and refused repayment.

When Kriger pressed him, Bowman exploded in rage.

The attack was savage and premeditated.

Bowman tried strangling Kriger first, and when that failed, pulled a knife.

Kriger survived only because he grabbed a glass bottle and struck Bowman across the face and neck, creating the permanent scars.

Other borders heard the struggle and intervened before Bowman could finish.

The police statement concluded with Kger’s words, “This man is dangerous.

He has no conscience.

I fear he will kill someone if not found.

I will not rest until justice is done.

Elizabeth sat back, absorbing those words.

Joseph Kger had vowed not to rest until justice was done.

Had he spent 5 years searching for the man who tried killing him? Had he been the one to track Bowman to Philadelphia? She needed to find what happened to Ysef Kger after 1897.

Elizabeth searched New York records, city directories, immigration documents, census data.

Kger appeared in the 1898 directory at a different address, recovered from his injuries, and still working as a carpenter.

He was listed again in 1899 and 1900.

But in 1901, Joseph Kger’s name appeared in the New York directory with a notation that caught Elizabeth’s attention.

Relocated to Philadelphia, the same year, the same city.

He had followed Bowman.

Elizabeth’s hands trembled as she searched Philadelphia city directories for 1901 and 1902.

There it was.

Joseph Kger, Carpenter, residing at an address on Germantown Avenue, less than two miles from where Friedrich Vagner lived with his family.

The timeline became devastatingly clear.

Kger had somehow discovered that Bowman was living in Philadelphia under a false name.

He had moved there in 1901, possibly spending months confirming the identity and planning his next move.

In early April 1902, he had confronted Bowman at his home.

The argument the neighbor overheard.

3 days later, Bowman was dead in an alley.

Elizabeth found the final piece of evidence in an unexpected place.

Ship passenger manifests from the port of Philadelphia.

In May 1902, one month after Friedick Vagner’s murder, Yseph Kriger departed Philadelphia on a vessel bound for Hamburg, Germany.

He was returning home, his pursuit complete.

He had hunted the man who tried to kill him for 5 years across state lines and through false identities.

And he had taken his revenge.

Then he had simply left, disappearing back to Germany, where American law couldn’t touch him.

The Philadelphia police had investigated Vagner’s murder, but they had no way of knowing the victim’s real identity or the violence history that led to his death.

They were looking for random street criminals or robbery gone wrong.

They never knew they were dealing with a calculated act of vengeance by a man who had traveled hundreds of miles to settle a blood debt.

Elizabeth shared her findings with Marcus and they sat in silence for a long moment contemplating the dark symmetry of it all.

A violent man who had tried to kill, who had fled and hidden and built a life on lies, ultimately killed by the very man he had victimized.

“We can’t prove definitively that Kriger killed him.

” Marcus finally said, “It’s circumstantial.

the timing, the relocation, the departure, but it’s compelling.

Elizabeth nodded.

Compelling enough to include in our findings with appropriate caveats.

But there’s still one more part of this story we need to understand.

What happened to Anna and the children after the murder? They’re the real victims here.

With Friedrich Vagner’s true identity and death circumstances understood, Elizabeth turned her attention to the family he left behind.

Hannah Wagner had been thrust into widowhood at age 33, left alone with three young children in a city where she had no extended family, no financial resources, and a murdered husband whose case remained unsolved.

Elizabeth traced Anna’s path through city records with growing sorrow.

The 1903 directory listed her as a widow still living at the North Second Street address, but her occupation had changed to seamstress, grueling, poorly paid work she could do from home while caring for her children.

The factory job Friedrich had held died with him.

The family’s primary income vanished overnight.

By 1904, Anna had moved to a cheaper address in a more densely packed immigrant neighborhood.

The children were old enough now to appear in school records, and Elizabeth found them enrolled at the local public school.

Wilhelm, 12, Otto, 10, Margarette, 8.

Attendance records showed frequent absences, particularly for Wilhelm, who was likely working odd jobs to help support the family.

Elizabeth discovered something heartbreaking in the school records.

A teacher’s notation from 1905 beside Wilhelm’s name stating, “Boy appears malnourished.

” Clothes worn and insufficient for winter weather recommend intervention by charity services.

The Vagner children were struggling, barely surviving on their mother’s meager seamstress wages.

Anna was working herself to exhaustion.

Elizabeth found her name in records of three different garment contractors who employed home seamstresses, meaning she was taking peacework from multiple sources, sewing late into the night to earn enough to feed her children.

In 1906, Anna made a desperate decision documented in the records of the Pennsylvania Orphan Society.

She had applied to place Otto, now 12 years old, in the society’s care.

Her application letter, preserved in the organization’s archives, was written in careful but imperfect English.

I cannot feed my son proper.

He is good boy, but I have no money for enough food and no money for good clothes for school.

My hands hurt from sewing, and I cannot see good anymore from the close work and dark.

Please take my boy and give him food and school.

I will take him back when I can work more.

Please help.

The application was approved and Otto was admitted to the Orphan Society’s home in June 1906.

The records indicated he would remain there until age 14 when he would be apprenticed to a trade, separated from his family, but at least guaranteed food, shelter, and basic education.

Elizabeth felt the weight of Anna’s impossible choice.

Anna’s struggles weren’t over after sending Otto to the orphanage.

In 1907, Elizabeth found another record deepening the tragedy.

Anna Wagner admitted to Philadelphia General Hospital in November 1907, suffering from exhaustion, malnutrition, and advanced tuberculosis.

She remained hospitalized for 6 weeks before being discharged with a grim prognosis.

The tuberculosis, likely contracted from years of living in cramped, poorly ventilated tenementss while working herself to exhaustion, was advanced and untreatable in that era.

The hospital records noted she had two children still at home and asked repeatedly about her son in the orphanage, wanting to see him before it was too late.

Elizabeth searched death records with a heavy heart, knowing what she would find.

Anna Vagner died on March 22nd, 1908 at age 39.

The death certificate listed tuberculosis as the cause, but Elizabeth knew the real killers were poverty, overwork, and the burden of secrets she may never have fully understood.

Anna was buried in a potter’s field, a mass grave for the poor who couldn’t afford individual plots.

There was no headstone, no memorial, just a notation in a ledger.

Wagner Anna unmarried.

The clerk apparently unaware she was a widow.

Or perhaps the distinction didn’t matter for someone buried in a popper’s grave.

Elizabeth sat in the archives reading room, tears blurring her vision as she contemplated Anna’s life.

A woman who had married in good faith, raised three children, worked herself literally to death trying to provide for them and died alone in a charity hospital, buried in an unmarked grave.

She had done nothing wrong, yet she had paid the ultimate price for her husband’s violence and deception.

The photograph from 1901 now carried even more weight.

It showed a family that looked respectable and hopeful.

Captured in a moment before everything fell apart.

Anna’s hand resting on Friedick’s shoulder, not knowing who he really was.

The children standing proudly in their best clothes, unaware that within 7 years they would be scattered.

One in an orphanage, their mother dead, their family destroyed.

With Anna’s tragic death documented, Elizabeth knew she needed to trace what happened to the three children, Wilhelm, Otto, and Margaret, who had been orphaned by ages 14, 12, and 10, respectively.

She started with Wilhelm, the oldest, who at age 16 had suddenly become responsible for himself and his younger sister after his mother’s death.

School records showed he had stopped attending classes in early 1908, immediately after Anna died.

City directory listings indicated he found work as a factory laborer, likely in one of the textile mills that had employed his father.

In 1910, the census recorded Wilhelm, now 18, living in a boarding house and working as a machine operator.

There was no mention of his sister Margaret in connection with him.

Where had the 10-year-old Margaret gone when her mother died? The answer came from the records of the Catholic Home for Destitute Children, a Philadelphia orphanage run by the Sisters of Charity.

Margaret had been admitted there in April 1908, one month after Anna’s death, listed as orphaned, no living relatives able to care for her.

The notation indicated she had an older brother, but he was unable to provide suitable home for female child.

Wilhelm, barely more than a child himself, working exhausting factory hours just to feed himself, had made the agonizing decision to place his baby sister in an orphanage rather than try to keep her in his cramped boarding house room.

It was the same impossible choice his mother had made with Otto 2 years earlier.

Margarett’s records showed she remained at the orphanage until 1916 when at age 18 she was placed in domestic service with a wealthy family in the suburbs.

This was standard practice.

Orphanages trained girls and household skills and then placed them as maids, cooks, or nannies.

Otto’s path was somewhat different.

The orphan society records showed he had remained in their care until 1910 when at age 16 he was apprenticed to a printing company, a skilled trade that offered better prospects than factory work.

Elizabeth traced Otto through subsequent city directories.

He completed his apprenticeship and became a journeyman printer.

In 1920, at age 26, Otto married a woman named Ruth.

They appeared together in the 1920 census, living in a modest but respectable neighborhood.

Otto working as a printer, Ruth as a homemaker.

Of the three siblings, Otto seemed to have achieved the most stable life.

But Elizabeth noticed something poignant in his World War I draft registration.

When asked to list his nearest relative, Otto had written none.

At age 24, he had no contact with his brother or sister.

The Vagner family had been completely fractured.

Wilhelm’s later life proved harder to trace.

He appeared sporadically in city directories through the 1910s, moving frequently between boarding houses and factory jobs.

In 1918, he registered for the draft and was inducted into the army, serving in France during the final months of the war.

He returned to Philadelphia in 1919, but his path afterward became unclear.

Elizabeth found one final record of Wilhelm from 1924, a death certificate listing Wilhelm Vagner, age 32.

Cause of death, accidental workplace injury.

He had been killed in a factory accident.

He died unmarried.

No children, no family listed, except sister, whereabouts unknown.

He was buried in a veteran cemetery, his military service granting him a dignity and death that had eluded his mother.

Elizabeth began preparing the findings for publication, working with Marcus to document every detail carefully and ethically.

They contacted descendants of Otto, who still lived in the Philadelphia area, explaining what they had discovered about the family’s tragic history.

The descendants were shocked to learn their ancestors father had been a violent criminal living under a false identity, but grateful to finally understand the fragmented family stories passed down through generations.

In September 2019, Elizabeth and Marcus published their research in the Journal of American Immigration History, accompanied by the enhanced photograph showing the hidden scar.

The article detailed Hinrich Bowman’s crime, his years hiding as Friedrich Vagnner, his likely murder by Yoseph Kger, and the devastating impact on Anna and her children.

The photograph that had hung forgotten in an archive for 118 years now told its complete story, not just of one man’s violence and deception, but of the innocent family that paid the price.

Anna’s hand resting on her husband’s shoulder, unaware of the darkness he carried.

The three children standing proudly, their futures already doomed by secrets they couldn’t know.

The scar in the photograph, hidden for over a century, had revealed a truth that changed everything.

Not because it exposed a criminal, but because it illuminated the real victims.

A widow who worked herself to death, children scattered to orphanages and hard labor, a family destroyed by one man’s past.

When people looked at the photograph now, they saw what had been hidden.

Not just a physical scar, but the invisible scars left on innocent lives by violence, lies, and the inescapable weight of the

News

🔥 Vatican Meltdown as “Pope Leo XIV” Allegedly Unseals a Forbidden Scroll Said to Rewrite Christ’s Final Words and Expose Centuries of Holy Silence — In a voice dripping with irony and suspense, insiders whisper that a newly crowned pontiff stared down trembling cardinals and hinted at a dust-choked parchment hidden since the crucifixion itself, a so-called final commandment rumored to demand compassion over power, shaking faith, egos, and vault doors while skeptics snarl and believers gasp, because nothing rattles Rome like the suggestion that heaven’s last memo was buried on purpose and now the walls are listening 👇

The Revelation of Pope Leo XIV: A Shocking Unveiling In the heart of the Vatican, a storm brewed beneath the…

This 1889 studio portrait looks elegant — until you notice what’s on the woman’s wrist

This 1889 studio portrait appears elegant until you notice what’s wrapped around the woman’s wrist. Dr.Sarah Bennett had spent 17…

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters—but then historians noticed their hands

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters, but then historians noticed their hands. The archive room of…

It was just a portrait of a soldier and his wife—until you notice what he’s holding

It was just a portrait of a soldier and his wife until you notice what he’s holding. The photograph arrived…

It was just a portrait of a mother — but her brooch hides a dark secret

It was just a portrait of a mother and her family, but look more closely at her brooch. The estate…

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920 — but pay attention to the groom’s hand

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920. But pay attention to the groom’s hand. The Maxwell estate…

End of content

No more pages to load