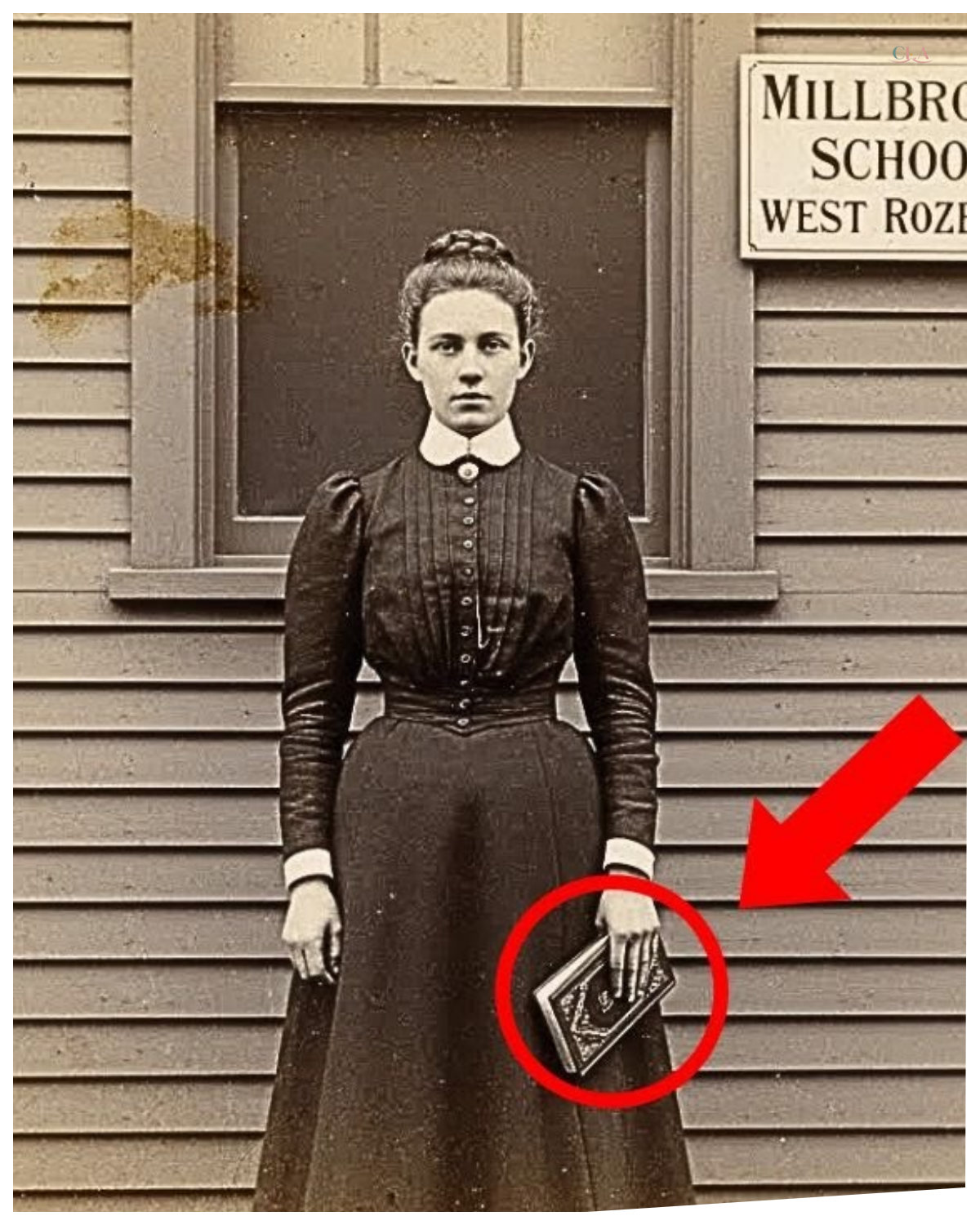

Why Were Experts Shocked by What the Woman’s Hand Revealed in This 19th-Century Photograph?

Why were experts shocked by what the woman’s hand revealed in this 19th century photograph? Rachel Morgan adjusted the angle of her desk lamp, illuminating the photograph that had arrived at the Boston Historical Preservation Society that morning.

The image was severely faded, its sepia tones washed out by more than a century of exposure to light and air.

A young woman stood before a simple wooden building, her posture rigid in the formal style of 1880s photography.

The photograph had been discovered in an estate sale in Brooklyn, tucked inside an old Bible with no identification except for a date pencled on the back.

September 1889, the woman wore a high collared dark dress with leg of mutton sleeves, her hair pulled back severely from her face.

One hand rested at her side while the other held something against her waist, a book of some kind, though the details were too degraded to make out clearly.

Rachel had been restoring historical photographs for 12 years, and she approached each one with the same methodical care.

She positioned the photograph on her highresolution scanner, adjusting the settings to capture the maximum possible detail.

The machine hummed softly as it began its work, translating the physical image into millions of digital pixels.

As the scan appeared on her monitor, Rachel began the painstaking process of digital restoration.

She worked layer by layer, adjusting contrast, recovering faded details, removing spots and scratches that time had inflicted on the original print.

The woman’s face gradually emerged from the fog of degradation.

She was young, perhaps in her mid-ents, with sharp, intelligent eyes that seemed to look directly through the camera.

Rachel zoomed in on various sections of the image, examining each area for damage that needed repair.

When she reached the woman’s hands, she increased the magnification to work on the fine details.

The book became clearer.

It appeared to be a small volume with an ornate cover, possibly a prayer book or journal.

Then Rachel saw something that made her pause.

Between the woman’s fingers, partially obscured by the angle of her hand, was a thin strip of paper.

She enhanced the image further, sharpening the focus until individual fibers of the paper became visible.

There was writing on it, cramped, tiny handwriting that ran the length of the strip.

Rachel’s heart began to beat faster.

In all her years of restoration work, she had learned that people in historical photographs sometimes held objects of significance, items that told stories beyond what the camera initially revealed.

But this was different.

This paper appeared to have been deliberately positioned to be hidden yet preserved.

She needed to know what was written on that strip of paper.

and more importantly who this woman was and why she had chosen to conceal a message in such an unusual way.

Rachel spent the next hour working exclusively on the woman’s hand, using every digital tool at her disposal to enhance the faded writing on the partially visible paper strip.

The letters were impossibly small, written in a careful, precise script that suggested education and deliberation.

Slowly, painstakingly, words began to emerge.

She could make out fragments.

Raw Johnson and Becca and what appeared to be Martinez.

The strip contained names, a list of some kind, written so small that it could only be read with significant magnification.

Rachel counted at least seven distinct names, though parts of the list remained hidden behind the woman’s fingers or were too degraded to decipher.

Why would someone hold a list of names in a photograph? And why write them so small, positioning them to be barely visible? Rachel turned her attention to the building in the background.

The structure was simple.

Wooden clabbered siding, a pitched roof, two visible windows with shutters.

A sign hung above what appeared to be the entrance, but it was blurred and unreadable in the original photograph.

She worked on that area next, carefully enhancing contrast and sharpness.

Letters appeared.

Uh, Brooke school.

It was a schoolhouse.

The woman was standing in front of a school.

Rachel felt a tingle of excitement.

A teacher, perhaps? that would explain the formal pose in the book she held, but it didn’t explain the hidden list of names or why the photograph had been preserved in a Bible with no other identification.

She needed more context.

Rachel opened her browser and began searching historical records for schools in the Boston area, operating in 1889.

There were dozens.

The late 19th century had seen an expansion of public education throughout Massachusetts.

She narrowed her search to schools in Brooklyn and the surrounding towns, looking for any establishment that might match the building in the photograph.

After an hour of searching through digitized archives and historical society’s databases, Rachel found a reference to Milbrook School, a small rural schoolhouse that had operated in West Robury from 1872 to 1903.

The building description matched what she could see in the photograph.

Wooden construction, two- room layout serving a farming community on the outskirts of Boston.

She found a roster of teachers who had worked at Milbrook School during its operational years.

In 1889, the teacher had been a woman named Elellanar Hayes, aged 24, hired in September of that year.

It was her first teaching position after completing her education at Boston Normal School.

Rachel stared at the woman in the photograph with new understanding.

Elellanar Hayes, a young teacher at a rural school in 1889, holding a book and concealing a list of names in her hand during what should have been a straightforward professional portrait.

But the story didn’t end there.

Rachel’s search had also turned up something else.

A newspaper article from March 1890, just 6 months after the photograph had been taken.

Local teacher missing.

The headline read, “Elanor Hayes disappears without trace.

” Rachel printed the newspaper article and spread it across her desk alongside the enhanced photograph.

The article was brief, offering few concrete details about Eleanor Hayes’s disappearance.

According to the report, Elellanar had failed to appear for classes on March 3rd, 1890.

When concerned parents visited her boarding house, they found her room empty, her belongings gone, and no note explaining her sudden departure.

The land lady had told reporters that Elellanar paid her rent through the end of February and left during the night of March 2nd.

No one had seen her leave.

No one knew where she had gone.

The school board had quickly hired a replacement teacher, and within weeks, Elellanar Hayes had become a footnote in local history, a mystery never solved.

Rachel read the article three times, studying the sparse facts for any connection to the photograph.

Why would a young teacher disappear so suddenly? And what did the list of names in her hand have to do with it? She began searching for more information about Elellanar Hayes, diving deeper into historical records.

Birth records showed she had been born in Boston in 1865 to a middle-class family.

Her father was a clerk, her mother a seamstress.

Eleanor had attended public schools and graduated from Boston Normal School in 1888, receiving certification to teach elementary students.

References from her training program described her as exceptionally dedicated and possessing strong moral convictions regarding education.

One letter of recommendation noted that Ellaner had volunteered to tutor children from impoverished families during her student teaching period, often working without compensation.

Rachel found the schoolboard minutes from Milbrook School’s records, digitized and archived by a local historical society.

Ellaner’s hiring had been routine.

She was the only qualified applicant for the position when the previous teacher retired.

The minutes from her first 3 months showed nothing unusual.

Attendance reports, curriculum notes, requests for supplies.

Then, in the January 1890 minutes, Rachel found something odd.

A parent had filed a formal complaint, though the specific nature of the complaint was recorded only as matters of instruction inappropriate to the community standards.

The school board had met with Ellaner privately, and the minutes simply stated, “Miss Hayes was counseledled regarding proper curriculum.

Matter considered resolved.

” But clearly, it hadn’t been resolved.

2 months later, Ellaner had vanished.

Rachel looked again at the photograph, at Ellanar’s serious face and the careful way she positioned her hand to hide yet preserve that list of names.

The pieces were beginning to form a pattern, though the full picture remained unclear.

She needed to find out who those names belong to.

The people Elellanor had considered important enough to secretly include in her photograph.

Sarah Johnson, Rebecca Martinez, and at least five others whose names were still hidden or too degraded to read.

Rachel began searching historical records for those two names, limiting her search to the West Roxbury area in the year 1889.

School enrollment records would be the logical place to start, but many such records from that era had been lost or destroyed.

She would need to get creative, searching through census data, church records, and any other documents that might have survived.

3 days later, Rachel sat in the reading room of the Massachusetts State Archives, surrounded by census records, property deeds, and municipal documents from the 1880s and 1890s.

She had spent hours searching for any mention of Sarah Johnson or Rebecca Martinez in the West Roxbury area, and her persistence was finally yielding results.

She found Sarah Johnson first.

The 1890 census listed her as an 11-year-old girl living with her parents, James and Martha Johnson, on a small farm outside West Robury.

The occupation column for James was marked farm laborer, and a notation indicated the family was colored, the census terminology for African-American residents.

Rachel’s breath caught.

an African-American child in 1889 in a rural Massachusetts community.

She began to understand why Sarah’s name might need to be hidden.

Rebecca Martinez was harder to find, but Rachel eventually located her in immigration records.

The Martinez family had arrived in Boston from Mexico in 1885.

By 1889, they were living in West Roxbury, where the father worked in a textile mill.

Rebecca would have been 9 years old when the photograph was taken.

The pattern was becoming clear, and it was both inspiring and heartbreaking.

Rachel pulled out her notebook and began writing down what she knew, what she could prove, and what she suspected.

In 1889, Massachusetts had no explicit segregation laws like the southern states.

But social customs and economic barriers meant that children of color and immigrant children rarely received the same educational opportunities as white children from established families.

Many rural schools turned away black students or children from immigrant families, citing community standards or lack of resources.

Some communities operated separate, inferior schools for these children.

Others simply denied them education entirely.

Elellanar Hayes had been teaching at Milbrook School, a school that officially served the children of white farming families in the area.

But the photograph suggested something more, that Elellanar had been secretly teaching additional students, children who weren’t supposed to be there.

Rachel returned to the enhanced image on her laptop, studying the list of names with new understanding.

These weren’t just random names.

They were Elellanar’s secret students, children she was teaching in defiance of community expectations and possibly in violation of the informal rules that governed who could receive education.

The list was Elellanar’s record, her way of documenting who she had helped, and she had hidden it in plain sight in a photograph that appeared to show nothing more than a teacher posing before her school.

But why had Elellaner disappeared? Had someone discovered what she was doing? The parent complaint in January 1890, matters of instruction inappropriate to the community standards, suddenly took on new meaning.

Someone had found out about her secret students, and Elellanor had been warned to stop.

She hadn’t stopped.

2 months later, she had vanished, taking her belongings and leaving no forwarding address.

Was she running from something, or had something worse happened to her? Rachel needed to find more names from the list, more of Ellanar’s secret students.

If she could identify them all, she might be able to piece together what had happened in those final weeks before Elellanar Hayes disappeared.

Rachel requested the complete schoolboard records for Milbrook School, hoping to find more details about the January 1890 complaint against Elellanor.

The archive staff produced a thick bound volume containing handwritten minutes, correspondence, and administrative documents from 1872 to 1903.

She paged through carefully, finding the section covering Elellanar’s tenure.

The minutes confirmed what she had seen in the digitized version, but attached to the January meeting notes was something more, a letter from a parent preserved in the official record.

The letter was written by a man named Robert Ashford, identifying himself as a concerned taxpayer and parent of two students at Milbrook School.

His complaint was specific and damning.

It has come to my attention that Miss Hayes has been permitting colored children and foreign children to attend instruction alongside proper students.

I have personally observed several such children leaving the schoolhouse in the evening hours.

This is not what our community pays taxes to support, and it sets a dangerous precedent that undermines the natural order of society.

I demand immediate action to cease this inappropriate practice.

Or Rachel read the letter twice, anger building in her chest.

Elellanar had been teaching additional students in the evening after regular school hours, giving them the education they were denied elsewhere, and someone had reported her for it.

The school board’s response, recorded in the minutes, had been cautious.

They acknowledged Mr.

Ashford’s concerns, but noted that Eleanor was teaching these additional students on her own time without use of public resources beyond the schoolhouse building itself.

The board had counseledled Elellanor to exercise discretion, but stopped short of forbidding the practice outright.

It seemed the board members were caught between competing pressures, parents like Ashford, who opposed any education for non-white children, and their own recognition that Elellanar wasn’t technically violating any rules by volunteering her time.

But the compromise hadn’t satisfied anyone.

Rachel found another document dated February 15th, 1890, a petition signed by 15 parents demanding Elellanor’s dismissal.

The petition was more inflammatory than Ashford’s original letter claiming that Elellanar was corrupting the morals of white children by promoting racial mixing and encouraging foreign influence.

The school board had scheduled a meeting for March 10th, 1890 to address the petition and determine Eleanor’s future employment.

But Eleanor had disappeared on March 2nd, more than a week before that meeting could take place.

Had she fled to avoid being fired? Or had something more sinister occurred? Rachel found a clue in another document.

A letter from Elellanar to the school board chairman dated February 20th, 1890.

The letter was brief but passionate.

I understand that my actions have caused controversy in the community.

However, I cannot in good conscience turn away children who seek knowledge.

Every child, regardless of their family’s origin or the color of their skin, deserves the opportunity to read, write, and better themselves.

If teaching them makes me unsuitable for this position, then I accept that consequence, but I will not apologize for doing what is right.

It was a statement of principle, defiant and uncompromising.

Elellanar had known she might lose her job, but she had been prepared to face that outcome rather than abandon her students.

Yet, she had disappeared before the board could make their decision.

The timing suggested careful planning.

Elellanar had left on her own terms, not waiting to be dismissed or publicly condemned.

Rachel looked again at the photograph, understanding now why Elellanar had posed with that hidden list of names.

It was her documentation, her proof that these children existed and had received education despite every obstacle placed in their way.

The photograph was Ellaner’s testimony, preserved for a future that might be more just than her present.

Rachel returned to her research with renewed focus, determined to identify all the names on Elellanar’s hidden list.

She had Sarah Johnson and Rebecca Martinez confirmed.

Now she needed to find the others.

Working with the enhanced digital image, Rachel spent hours studying every visible letter on the paper strip.

She could make out partial names.

Booking wellchen a um a writing was so small and the paper so faded that even with maximum enhancement, some sections remained illegible.

She began systematically searching a census records and immigration documents for Chinese families in the West Roxbury area in 1889.

The Chen name suggested a Chinese immigrant family which would have faced severe discrimination during that era.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, had created a hostile environment for Chinese immigrants throughout the United States.

In the 1890 census, Rachel found a Samuel Chen, aged 10, living with his parents, who operate a small laundry service.

The family had immigrated from Guangdong Province in 1884.

Samuel would have been 9 years old when Ellaner took her photograph, exactly the age to benefit from basic education in reading and arithmetic.

The name a stone was more challenging.

After searching multiple variations, Rachel found a Dina Stone, age 8, daughter of formerly enslaved parents who had migrated north after the Civil War.

The Stone family worked as domestic servants for several wealthy households in the area.

Rachel was building a picture of Elellanar’s secret classroom.

Children from families that existed at the margins of 1889 Massachusetts society.

Black children whose parents had escaped slavery or been born free in the North.

Immigrant children from Mexico, China, and likely other countries.

These were the children deemed inappropriate for education alongside the white farming community’s sons and daughters.

She found property records showing that Ellaner rented a room above a general store in West Roxbury about a mile from the Milbrook School.

Her landlady, Mrs.

Harriet Walsh, had given that interview to the newspaper after Elellanar’s disappearance.

Rachel wondered if Mrs.

Walsh might have left other records, diaries, letters, anything that might provide more information about Eleanor’s final weeks.

A search through the historical society’s genealological records revealed that Mrs.

Walsh had died in 1912 and her papers had been donated to a local church.

Rachel contacted the church office explaining her research.

The secretary was intrigued by the story and promised to search their archives for any documents related to Harriet Walsh.

3 days later, Rachel received a call.

The church had found a box of Mrs.

Walsh’s personal papers, including a diary she had kept from 1888 to 1892.

Rachel drove immediately to collect the diary, her hands trembling slightly as she accepted the fragile volume.

That evening, she sat in her apartment, reading Harriet Walsh’s entries from late 1889 and early 1890.

The land lady had written about Elellanar with obvious affection, describing her as a serious young woman with strong convictions, who often worked late into the evening preparing lessons for her students.

Then, in a February entry, Mrs.

Walsh wrote something that made Rachel’s heart race.

Miss Hayes is troubled by the situation at the school.

She told me tonight that she may need to leave West Robury soon for her own safety and for the safety of the children she teaches.

She has been receiving threatening letters.

Rachel read Mrs.

Walsh’s diary entries from February 1890 with growing alarm.

The land lady had documented Ellaner’s increasing anxiety during those final weeks, though she seemed not to fully understand the danger her tenant faced.

February 10th, 1890.

Miss Hayes received another letter today.

She burned it in the stove without letting me see it, but I could tell from her face that it contained nothing pleasant.

She asked if I knew of any position for a teacher in another town far from here.

February 18th, 1890.

Found Miss Hayes in the parlor late tonight copying something from her school records.

She said she was documenting her students progress in case anything happened to her records.

An odd thing to say.

When I asked what she meant, she only smiled sadly and said, “History has a way of erasing the people it finds inconvenient.

” February 26th, 1890.

Miss Hayes has been burning papers all week.

She told me she’s decided to accept a position elsewhere, though she hasn’t said where.

She seems afraid, though she tries to hide it.

This morning, I found her staring at a photograph she had taken last autumn before all this trouble began.

The photograph Elellanar had been looking at, it had to be the one Rachel was restoring, the image with the hidden list of names.

Elellanar had been preparing to leave, documenting her work, preserving evidence of what she had done before disappearing.

The final entry about Elellanar was dated March 2nd, 1890.

Miss Hayes left during the night.

She paid everything she owed and left a note thanking me for my kindness.

The note said she hoped to continue teaching somewhere she could do the most good.

She asked me not to tell anyone where she had gone, but she didn’t tell me anyway.

I pray she finds peace wherever she’s headed.

This town has not treated her well.

So Elellanar had left voluntarily, fleeing threats and preparing for her dismissal by taking a position elsewhere.

But where had she gone? And had she continued teaching under her own name, or had she adopted a false identity to escape her reputation? Rachel needed to find Elellanar Hayes’s trail after she left West Roberry.

She began searching historical records from surrounding states, looking for any teacher named Elellanar Hayes, hired in spring 1890.

The search proved frustrating.

Hayes was a common surname, and Elellaner was a popular name in that era.

She found dozens of possible matches in Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, and beyond.

Then Rachel had another idea.

If Eleanor had been forced to use a false name, she might have chosen something close to her real identity.

A variation that would be easy to remember and respond to naturally.

Rachel began searching for variations.

Ellen Hayes, Norah Hayes, Ellaner Harris, Ellaner Hail.

In the Hartford, Connecticut City directory from 1891, Rachel found an entry for Ellen Harris, teacher primary school.

The timing was right.

Someone hired in 1890 would appear in the 1891 directory.

Hartford was far enough from Boston to provide distance from her troubles, but close enough to reach easily.

Rachel requested school records from Hartford’s historical archives.

When they arrived, she found employment records for Ellen Harris.

Hired in March 1890 to teach at a small school in Hartford’s immigrant neighborhood.

The records provided no prior employment history.

Unusual as most teaching positions required references.

It was as if Ellen Harris had appeared from nowhere.

But there was more.

The school Ellen Harris taught at served primarily immigrant children, Irish, Italian, Polish, and Jewish students whose families had recently arrived in America.

It was exactly the kind of position Elellanar Hayes would have sought, continuing her mission of teaching children who face discrimination and barriers to education.

Rachel traveled to Hartford to examine the school records in person.

The Hartford Historical Society maintained extensive archives of the city’s educational institutions, and the librarian helped her locate documents related to the school where Ellen Harris had taught.

The records painted a picture of a dedicated teacher working in difficult conditions.

The school served one of Hartford’s poorest neighborhoods, where most families struggled to keep their children in classes rather than working to support the household.

Ellen Harris taught students ranging from age 6 to 14, many of whom spoke little English when they arrived in her classroom.

Rachel found curriculum notes in Ellen’s handwriting, lesson plans that emphasized practical literacy and mathematics with a focus on helping students navigate their new country.

The handwriting was precise and careful with distinctive letter formations that matched the writing on the hidden list in Elellanar’s photograph.

But the most compelling evidence came from a school inspection report dated October 1891.

The inspector had written, “Miss Harris demonstrates exceptional dedication and skill in her teaching.

However, she maintains an unusual practice of offering additional evening instruction to students whose families cannot afford to lose their labor during day hours.

While commendable, this practice raises questions about Miss Harris’s personal background and training, about which she has provided limited information.

Evening instruction for students who couldn’t attend during the day, exactly what Ellanar Hayes had done in West Roxbury.

Rachel felt certain now that Ellen Harris and Elellanar Hayes were the same person.

She searched for more records of Ellen’s life in Hartford.

City directories showed her living in a boarding house near the school.

Church records indicated no religious affiliation or membership.

There were no society memberships, no social connections documented.

Ellen Harris lived quietly, dedicating herself entirely to her teaching.

Then in 1895, Ellen Harris disappeared from Hartford’s records as suddenly as Ellener Hayes had vanished from West Roxbury.

No forwarding address, no mention of resignation or departure.

The schoolboard minutes simply noted, “Position vacated by Miss Harris.

New teacher required.

” Rachel felt a mixture of frustration and admiration.

Elellanar had spent 5 years in Hartford, teaching hundreds of immigrant children before moving on again.

But where had she gone next? And how many times had she reinvented herself, always seeking places where she could teach the children others refused to educate? The pattern suggested Elellanar had spent her entire adult life moving from place to place, teaching under different names, always staying just ahead of controversy or discovery.

It was a lonely existence, cut off from family and forced to hide her true identity.

But it allowed her to continue the work she believed in.

Rachel expanded her search looking for women matching Elellanar’s age and description who appeared in teaching positions around 1895 in cities with significant immigrant populations.

She found possibilities in Providence, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, all cities where a dedicated teacher could find students in need.

In Baltimore’s school records, Rachel found a Miss E.

Hastings hired in 1896 to teach at a school serving black students in a segregated neighborhood.

The age was right, the timing fit, and the handwriting in the employment application matched Ellaner’s distinctive script.

Elellanar Hayes had continued her mission, adapting to whatever name and location would allow her to keep teaching the children society wanted to ignore.

Rachel stood in what remained of the Baltimore school where E.

Hastings had taught from 1896 to 1904.

The building had been converted into a community center decades earlier, but the structure retained its original bones.

High ceilings, large windows designed to maximize natural light, wooden floors worn smooth by generations of small feet.

The current director of the community center, an elderly man named James, listened with fascination as Rachel explained her research.

“My grandmother attended this school,” he said quietly.

“In the early 1900s, when it was one of the few places black children could get an education in Baltimore, she spoke often about a white teacher who taught here.

Said the woman was different from the others, that she genuinely cared about her students.

Do you remember your grandmother’s teacher’s name? Rachel asked, though she already knew the answer.

Miss Hastings.

My grandmother said, “She was the finest teacher she ever had.

Strict but fair and absolutely dedicated to making sure every child could read and write well enough to make their own way in the world.

” James led Rachel to a storage room where boxes of old school records had been preserved.

Together, they searched through attendance logs, grade books, and curriculum materials.

Ellaner, now using the name E.

Hastings had taught at the school for eight years, longer than any of her previous positions.

In a box of personal items donated by former students, Rachel found a photograph from 1903.

It showed Miss Hastings standing with her class of 25 students, all of them dressed in their best clothes for the formal portrait.

Ellaner would have been 58 years old by then, her hair now gray, her face lined with age, but her eyes still held the same intelligent, determined expression Rachel recognized from the 1889 photograph.

She stayed here until the school closed in 1904, James explained.

The city consolidated several schools and Miss Hastings was offered a position at the new facility, but according to my grandmother, she declined.

Said it was time for her to retire.

Rachel found the final document she needed in the employment records, a letter of resignation from E.

Hastings dated June 1904.

The letter thanked the school board for the opportunity to serve and expressed hope that education would continue to improve for all children regardless of their circumstances.

It was Elellanar’s last known teaching position.

Rachel searched death records, cemetery records, and city directories, trying to trace where Elellanar had gone after leaving Baltimore.

She found nothing definitive, though she discovered an e Hastings listed in a Philadelphia boarding house directory from 1905.

Age 60, occupation listed as retired teacher.

Elellanar Hayes had lived to at least age 60, spending her entire adult life teaching children who had been denied education by others.

She had worked under multiple names in multiple cities, always moving on before her past could catch up with her.

Always seeking students who needed her most.

The photograph from 1889 with its hidden list of names had been Ellaner’s way of preserving a record of her work.

Proof that these children had existed had learned had mattered.

Sarah Johnson, Rebecca Martinez, Samuel Chen, Dina Stone, and the others whose names Rachel had painstakingly identified.

They represented hundreds, perhaps thousands of students Ellanar had taught across her career.

Rachel thought about the courage it must have taken to live such a life.

Always hiding, always moving, never able to form lasting personal connections or publicly acknowledge her accomplishments.

Eleanor had sacrificed everything for her principles, giving up her own identity to ensure that others could develop theirs through education.

6 months after discovering the hidden list in Elellanar Hayes’s photograph, Rachel stood in a conference room at the Boston Historical Society preparing to present her findings.

The room was filled with historians, educators, and descendants of the students Elellanar had taught.

People whose ancestors names appeared on that carefully concealed strip of paper.

Rachel had tracked down living descendants of five of Elellanar’s secret students from West Roxbury.

Sarah Johnson’s great great granddaughter, a retired physician named Dr.

Patricia Williams, had traveled from Atlanta to attend.

The Martinez family was represented by three generations, including 92-year-old Robert Martinez, whose grandfather had been Rebecca’s younger brother.

Elellanar Hayes lived a life that required constant vigilance and sacrifice.

Rachel began her presentation.

She taught children that society deemed unworthy of education.

When discovered, she didn’t fight publicly or seek recognition.

She simply moved on, found new students who needed her, and continued her work under a different name.

Rachel displayed the enhanced photograph showing the hidden list of names clearly visible on the screen.

This photograph taken in September 1889 contains the names of at least 12 students Ellaner taught secretly in the evenings after her regular school day ended.

These children, black children, immigrant children, the children of the poor and marginalized, received an education that changed the trajectory of their families for generations.

Dr.

Williams spoke next, her voice thick with emotion.

My great great grandmother, Sarah Johnson, learned to read from Elellanar Hayes.

Because Sarah could read, she was able to help her younger siblings with their education.

Because they were educated, they found better employment and opportunities.

My grandmother became a teacher herself, inspired by the stories of Miss Hayes that had been passed down.

I became a doctor.

All of this traces back to a woman who risked everything to teach a young black girl in 1889.

The Martinez family shared similar stories.

Rebecca Martinez had used her education to work as a translator and advocate for other immigrant families.

Her children attended college, something almost unheard of for Mexican immigrant families in that era.

Each generation had built upon the foundation Elellanar Hayes had provided.

Rachel had created a digital archive documenting Elellanar’s known teaching positions and the students she had helped.

The archive included the original photograph, census records, school documents, and oral histories collected from descendants.

It painted a picture of a woman who had spent 40 years teaching under various names in six different cities, always seeking out the students most in need of education.

The Historical Society announced that they would install a permanent exhibit about Elellanar Hayes, highlighting her courage and dedication to educational equality.

Local schools in the communities where Ellaner had taught planned to name scholarships in her honor.

Under all her names, Ellaner Hayes, Ellen Harris, E.

Hastings, and the others she had used throughout her career.

What strikes me most, Rachel said in closing, is that Ellaner never sought recognition.

She could have fought her dismissal publicly, made herself a martyr for the cause of educational equality.

Instead, she quietly continued her work, touching hundreds of lives while remaining anonymous.

The only evidence she left behind was this photograph with its hidden message, a testament not to her own courage, but to the children she believed in.

Rachel projected the enhanced image one final time, showing Elellanar’s serious face and the carefully positioned hand concealing the list of names.

For 135 years, this photograph was just a portrait of a young teacher.

But Ellaner knew something.

We’re only now understanding that sometimes the most powerful testimony is the one hidden in plain sight, waiting for a future generation to recognize its significance.

Um, the audience sat in silence for a moment, absorbing the weight of Ellaner’s story.

Then Dr.

Williams stood, followed by the Martinez family and then everyone in the room, offering a standing ovation for a woman who had died decades earlier, never knowing that her secret would eventually be revealed and celebrated.

After the presentation, Rachel stood before the enhanced photograph, studying Elellanar’s face one final time.

The young woman who had posed in front of Milbrook School in 1889 had known she was taking a risk, documenting evidence of work that could have destroyed her career.

But she had also known that documentation mattered, that names mattered, that someday someone might care enough to look closely and understand.

Elellanar Hayes had trusted in the future.

She had trusted that justice and equality would eventually prevail, that her students descendants would live in a world where their education wasn’t controversial but celebrated.

And she had left behind a single photograph with a hidden message, waiting patiently for the technology and perspective that would allow it to be seen.

Rachel thought about all the other historical photographs sitting in archives and attics, images that appeared ordinary but might contain similar secrets.

How many other Elellanar Hazes were waiting to be discovered? There’s stories of courage and sacrifice concealed in plain sight.

The photograph would remain on display at the historical society with a detailed explanation of what Ellanar had hidden in her hand and why.

Visitors would be able to see both the original image and the enhanced version showing the list of names clearly.

Ellaner’s testimony preserved for 135 years would finally be heard.

And the children whose names she had protected.

Sarah, Rebecca, Samuel, Dina, and the others would be remembered not as people who were denied education, but as students of a remarkable teacher who believed every child deserved the opportunity to learn, regardless of what society thought.

Elellanar Hayes had spent her life moving through shadows, always teaching, never acknowledged.

But her photograph had remained carrying its secret forward through time until the moment when technology and determination could reveal what she had always wanted the world to know.

that these children existed, that they learned, and that they mattered.

News

Why were historians turned pale when they zoomed in on this 1887 wedding portrait? The basement archive of the Chicago Historical Museum smelled of old paper and dust, a scent that Dr. Rachel Thompson had grown to love over her 15 years as a curator. On this particular October morning in 2024, sunlight filtered weekly through the high windows, casting long shadows across rows of storage boxes, waiting to be cataloged. Rachel sat at her workstation, methodically scanning photographs from a recent estate donation. her eyes tired but alert. The collection had belonged to the Patterson family, descendants of early Illinois settlers who had finally decided to part with their ancestral archives. Most of the photographs were predictable. Stern-faced ancestors in formal poses, faded images of farmland, a few Civil War soldiers standing rigidly before the camera. Rachel had processed dozens of similar collections, and she worked efficiently, noting dates and names in her database. Then she reached a photograph that made her pause.

Why were Historians Turn Pale When They Zoomed In on This 1887 Wedding Portrait? Why were historians turned pale when…

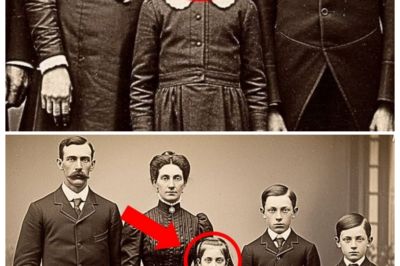

Historians Restored This 1903 Portrait — Then Noticed Something Hidden in the Man’s Glove Emma Brooks adjusted her computer screen, squinting at the sepia toned photograph that had arrived at the Pennsylvania Historical Society three days earlier. The image showed a family of five standing in a modest garden, their faces frozen in the stern expressions common to early 20th century portraits. The father stood at the center, one hand resting on his wife’s shoulder, the other hanging stiffly at his side. Three children flanked them, the youngest barely tall enough to reach her mother’s waist. The photograph had been donated by Katherine Miller, an elderly woman from Pittsburgh who claimed it showed her great-grandparents. Emma had seen hundreds of similar images during her 15 years as a photographic historian. But something about this one nagged at her. Perhaps it was the quality of the original print, remarkably well preserved despite its age, or the intensity in the father’s eyes that seemed to pierce through more than a century of distance.

Historians Restored This 1903 Portrait — Then Noticed Something Hidden in the Man’s Glove Emma Brooks adjusted her computer screen,…

Why Did Historians Become Pale When Enlarging the Face of the Younger Girl in This 1891 Image? The Haunting Revelation of the 1891 Portrait In the dim light of the archive room, Dr. Eleanor Hayes meticulously examined the faded photograph, its edges curling with age. The image depicted a young girl, her face innocent yet enigmatic, captured in a moment that transcended time. But as Eleanor enlarged the photograph, a chill ran down her spine. The girl’s eyes, once merely a reflection of childhood, now seemed to harbor secrets that could unravel history itself. Eleanor had dedicated her life to understanding the past, but this image was different. It was as if the girl was staring into her soul, demanding to be heard. The historians had warned her about this particular photograph, claiming it was cursed, a relic that had brought misfortune to those who dared to delve too deep. But Eleanor, driven by an insatiable curiosity, pressed on. As she zoomed in, the girl’s face transformed. The smile that once appeared sweet now twisted into something sinister.

Why Did Historians Become Pale When Enlarging the Face of the Younger Girl in This 1891 Image? The Haunting Revelation…

This 1901 studio portrait looks normal — until experts zoomed in on the child’s eyes Dr.Sarah Brennan’s hands trembled slightly as she adjusted the highresolution scanner over the faded photograph. The basement archive of the Boston Heritage Museum was cold, smelling of old paper and preservation chemicals. She had been cataloging donated Victorian photographs for 3 weeks now, and most had been unremarkable. Stiff portraits of forgotten families, their stories lost to time. This one seemed no different at first glance. A studio portrait dated 1901, stamped on the back with the name Whitmore Photography Studio, Lawrence, Massachusetts. A well-dressed couple stood rigid, the man’s hand on his wife’s shoulder. Between them sat a small girl, perhaps 6 years old, in a white-laced dress with ribbons in her dark hair. The child’s hands were folded neatly in her lap, holding a small bouquet of white liies. Sarah began the scanning process, watching as the digital image appeared on her computer screen in extraordinary detail.

This 1901 studio portrait looks normal — until experts zoomed in on the child’s eyes Dr.Sarah Brennan’s hands trembled slightly…

🚨 Greg Biffle’s last flight revealed in 60 seconds as a countdown compresses terror into heartbeats, timelines snap shut, and every routine check feels fateful while the sky turns witness to courage, pressure, and a moment that refuses to stay silent ✈️⏱️ the narrator slices time with a razor voice, hinting that when seconds decide legends, the truth doesn’t shout—it clicks, pops, and dares you to keep watching 👇

The Final Descent In the heart of the night, the engines roared like a beast awakened from slumber, echoing through…

End of content

No more pages to load