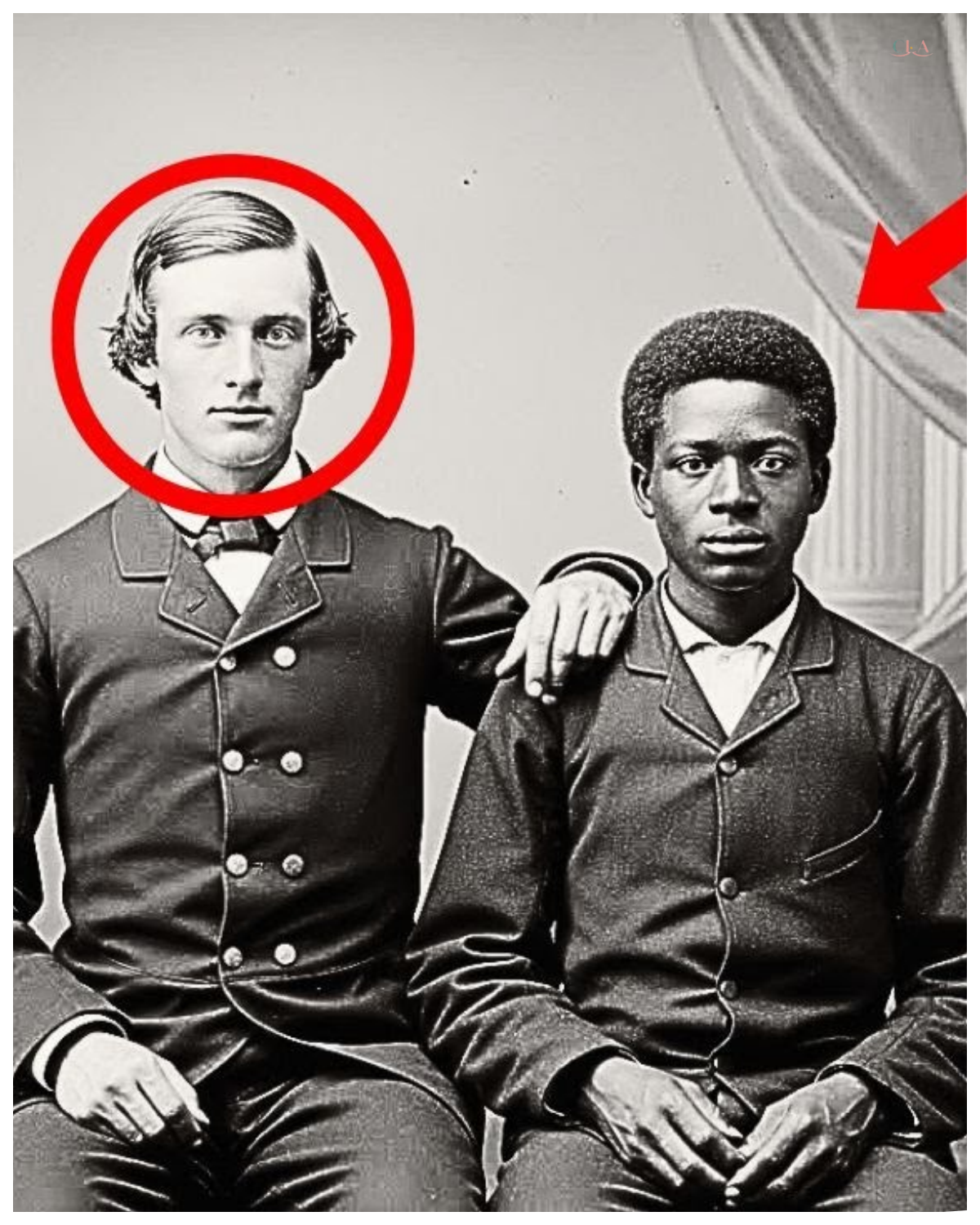

Why Were Experts Pale When Enlarging This Portrait of Two Friends from 1870?

Why were experts pale when enlarging this portrait of two friends from 1870? The afternoon light filtered through the tall windows of the Historical Preservation Society in Charleston, South Carolina, casting long shadows across Dr.

Rebecca Martinez’s cluttered desk.

She had been cataloging old photographs for nearly 3 weeks, her eyes tired from squinting at faded faces and cracked glass plates.

Most were routine, families posed stiffly in their Sunday best, children with blank expressions, soldiers frozen in time before unknown fates.

But this one was different.

Rebecca held the Dger type up to the light, her breath catching slightly.

Two young men, perhaps in their early 20s, stood side by side in what appeared to be a photography studio.

The backdrop was painted with classical columns and draped fabric, typical of the era.

One man was white with light hair swept back from his forehead, wearing a fine wool suit with brass buttons that caught the light.

The other was black, dressed in simpler but clean clothing.

A cotton shirt and dark vest, his posture remarkably relaxed for a photograph from 1870.

What struck Rebecca immediately was their proximity.

In an age when social conventions dictated rigid separation, these two stood close enough that their shoulders nearly touched.

The white man’s hand rested casually on the back of a chair between them, while the black man’s arms hung naturally at his sides.

But it was their expressions that truly captured her attention.

Not the typical stern faces of 19th century portraits, but something warmer.

The hint of a smile played at the corners of both mouths, as if they shared a secret the camera couldn’t quite capture.

Rebecca turned the photograph over carefully.

On the back, in faded brown ink, someone had written Thomas and Samuel, Charleston, April 1870.

No surnames, no other context, just two first names and a date.

The photograph had arrived that morning in a cardboard box from an estate sale in the countryside outside Charleston.

An elderly woman had passed away and her belongings were being dispersed.

Among the items, furniture, books, and household goods, was a small wooden trunk containing family documents and photographs.

This particular image had been wrapped in old tissue paper, preserved more carefully than the others, as if someone had wanted to protect it.

Rebecca set the dgeraype down and reached for her equipment.

The society had recently acquired a highresolution digital scanner specifically designed for delicate historical photographs.

If there were any details hidden in the image, dates, locations, or identifying marks, the scanner would reveal them.

As the machine hummed to life and began its meticulous work, Rebecca couldn’t shake the feeling that this simple portrait held something more than met the eye.

She glanced at the clock on the wall.

It was nearly 5:00 in the evening, and most of her colleagues had already left for the day.

The building was quiet, except for the soft mechanical wor of the scanner and the distant sound of traffic on the street below.

Outside, Charleston was beginning its transition into evening.

The historic district’s gas lamps were flickering to life, and tourists were wandering the cobblestone streets, admiring antabbellum architecture that stood as both monument and reminder of a complicated past.

Rebecca had lived in Charleston for 8 years now, ever since accepting her position at the preservation society.

And she still felt the weight of history pressing down on every corner of the city.

The beauty and the horror existed side by side here.

elegant town houses built with enslaved labor, churches where both masters and the enslaved had worshiped in segregated pews, monuments that told only half the story.

She returned her attention to the scanner, watching the progress bar slowly fill as it captured every microscopic detail of the dgerotype.

The scanning process took nearly 40 minutes.

Rebecca made herself a cup of coffee in the small breakroom down the hall, the aroma of dark roast filling the quiet space.

She leaned against the counter, watching the coffee maker drip and thinking about the photograph.

There was something about the way those two men stood together that nagged at her professional instincts.

She had seen thousands of photographs from the Civil War and Reconstruction periods, and this one broke too many unspoken rules.

When she returned to her desk, the digital image was fully loaded on her screen, rendered in extraordinary detail that the naked eye could never perceive.

The highresolution scan had captured textures and nuances invisible in the original.

every thread in the fabric, every subtle variation in the photographic emulsion, every minute detail that time and handling had obscured.

She adjusted her glasses and leaned forward, her fingers moving the cursor to zoom in on different sections of the photograph.

The studio details became clearer first.

She could now read the photographers’s mark embossed faintly in the corner.

Jay Weston, photographic artist, Charleston, SC.

She made a note to research Weston’s studio later, knowing that photographer registries from the reconstruction era might help narrow down the exact location and date.

The painted backdrop showed more detail, too.

Classical urns, draped fabric that mimicked expensive curtains, and what appeared to be a painted garden scene in the distance, all standard elements of portrait studios in the 1870s, designed to give working-class clients a taste of aristocratic elegance they could never afford in real life.

The floor visible at the bottom of the frame showed worn wooden planks, suggesting the studio was in an older building, possibly repurposed from some other commercial use.

Rebecca zoomed in on the faces next.

Thomas, the white man, she assumed, based on conventional naming patterns of the era, had sharp features and light eyes, possibly blue or gray.

His expression was controlled but not harsh.

There was something almost protective in the way he stood, his body angled slightly towards Samuel, as if unconsciously shielding him from an invisible threat.

His hair was neatly combed, and there was a small scar visible on his left cheek, perhaps from a childhood accident or illness.

Samuel’s face was more difficult to read, not because of the photograph’s quality, but because of the complexity of his expression.

His eyes looked directly at the camera with a steadiness that was unusual for the time.

Most black Americans photographed during this period either looked down or away, their poses dictated by the oppressive social norms that still governed interactions between races even after emancipation.

But Samuel met the lens headon, his gaze unwavering and proud.

His features were strong, high cheekbones, a firm jaw, eyes that suggested both intelligence and weariness.

Then Rebecca noticed something that made her pause.

She zoomed in further on Samuel’s left wrist, where his hand hung naturally at his side.

The sleeve of his shirt had pulled back slightly during the exposure, revealing a thin band of skin just above where his hand began.

At first, she thought it might be a shadow or a flaw in the photograph.

Perhaps damage to the original plate or a trick of the light during the long exposure time required for dgeray types.

But as she increased the magnification, her heart began to beat faster.

There were marks on Samuel’s wrist, faint but unmistakable, thin lines encircling the wrist, lighter than the surrounding skin.

Scar tissue, the kind of scarring that came from prolonged friction from something worn tightly for extended periods.

Rebecca had seen similar marks in other historical photographs and medical documentation from the era in the terrible archive of evidence that documented the brutality of slavery.

Shackles.

The scars left by iron shackles.

Rebecca sat back in her chair, her coffee forgotten and growing cold in her hand.

Her mind raced through the implications.

She zoomed out slightly, then moved to Samuel’s right wrist.

The angle was different, his arm positioned so that less of the wrist was visible, but she could make out similar markings there, too, though fainter.

The scarring was symmetrical, which suggested he had been restrained for long periods, possibly years.

The room suddenly felt colder.

Rebecca had cataloged hundreds of photographs from the Civil War and Reconstruction periods.

She had seen images of scarred backs bearing the evidence of whipping of families separated at auction blocks, of people who bore the physical evidence of enslavement on their bodies.

But this was different.

This photograph showed Samuel not as a victim in a documentary sense, but as a person, standing beside a white man in apparent friendship, smiling, meeting the camera’s gaze with dignity and self-possession.

Yet the scars remained, permanent testament to what he had endured.

They were like a ghost signature written on his body, visible only when examined closely, but impossible to erase.

Rebecca pulled out her notebook and began writing down everything she observed.

The date, April 1870, just 5 years after the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery.

The location, Charleston, a city that had been at the very heart of the Confederacy, one of the most important slave trading ports in North America.

The subjects, two young men whose relationship contradicted every social convention of their time and place.

She documented the scars in detail, noting their position, their appearance, and what they suggested about Samuel’s past.

She made sketches in her notebook, trying to capture the pattern of the scarring.

Then she took multiple screenshots at different magnification levels, saving them all in a dedicated folder on her computer.

As she worked, questions multiplied in her mind.

If Samuel had been enslaved, when was he freed? Who had enslaved him? What plantation or household had he belonged to? And most pressingly, what was his relationship to Thomas? Why would these two men, separated by the vast chasm of race and social status in the post-war South, choose to have their photograph taken together in this way? The photograph showed no signs of coercion or subservience.

This wasn’t a portrait of master and servant or employer and employee.

The body language was too relaxed, too familiar.

They stood like friends, like brothers, almost like equals, which in 1870 Charleston would have been not just unusual, but potentially dangerous.

She needed help with this.

This was bigger than a simple cataloging project.

This was a story that needed to be uncovered, researched, and told.

Rebecca checked the time, 7:30 in the evening.

The building was completely empty now, the cleaning staff having finished their rounds an hour ago.

The silence was profound, broken only by the hum of her computer and the occasional creek of the old building settling into the cool evening air.

She pulled out her phone and scrolled through her contacts until she found Marcus, a colleague and genealogologist who specialized in reconstruction era South Carolina families.

Marcus had worked at the state archives for over 15 years before semi-retiring to do private genealological research.

He helped families, both black and white, trace their lineages back through the chaos of slavery and reconstruction, piecing together family histories from fragmentaryary records, oral traditions, and whatever documentation had survived wars, fires, floods, and deliberate destruction.

He was meticulous, patient, and had an encyclopedic knowledge of Charleston area plantation records.

Rebecca typed out a text.

Found something unusual in a photograph from 1870.

Need your expertise.

Can you come by tomorrow morning? His reply came almost immediately.

I’ll be there at 8.

Coffee on you.

Rebecca smiled despite the weight of what she discovered.

She took one more long look at the photograph on her screen.

At Thomas and Samuel standing side by side in that Charleston studio, frozen in a moment of connection that had somehow survived for over 150 years.

She wondered what circumstances had brought them there to Jay Weston’s studio on King Street.

What had they been thinking as they stood before the camera? What did this photograph mean to them? She saved her work, backed up all the image files to the cloud, and finally allowed herself to leave.

Outside, Charleston had fully surrendered to nightfall.

The historic district was lit by street lamps and the warm glow from restaurant windows.

Tourists and locals filled the sidewalks, enjoying the mild spring evening.

Rebecca walked to her car, but her mind was still in 1870, still puzzling over the mystery of two friends whose story had been hidden in plain sight for generations.

That night, she couldn’t sleep.

She lay in bed thinking about the scars on Samuel’s wrists, about the smile on his face, about the way Thomas stood protectively beside him.

She thought about all the stories that had been lost to time, all the photographs that had been discarded or destroyed, all the evidence of human connection and courage that had disappeared because no one thought to preserve it or because preserving it would have been too dangerous.

This photograph had survived.

Someone had wrapped it carefully in tissue paper and kept it safe in a trunk for over a century.

That act of preservation was itself significant.

Someone had wanted this story to endure, had recognized that this moment mattered, that these two men and whatever relationship they shared was worth remembering.

Rebecca was determined to find out why.

Marcus arrived at 7:45 the next morning, 15 minutes early as usual, carrying two large coffees from the shop down the street.

He was a tall man in his early 50s with graying hair that he wore slightly too long and reading glasses that perpetually hung from a chain around his neck.

He set one coffee on Rebecca’s desk and pulled up a chair, his eyes already fixed on the large monitor where the photograph was displayed.

“Show me what you found,” he said, getting straight to business as he always did.

Rebecca walked him through the discovery, starting with the basic details, the date inscribed on the back, the studio location, the names Thomas and Samuel, before zooming in on the critical detail, the scars on Samuel’s wrists.

She explained what she believed they were, pointing out the pattern of scarring, the symmetry, the way the marks encircled both wrists.

Marcus leaned forward, his expression growing more serious with each detail.

He sat down his coffee and pulled his reading glasses up to examine the screen more closely.

He said nothing for a long moment, just studied the magnified image of Samuel’s scarred wrist.

“Those are shackle marks,” he finally said, his voice quiet.

“No question about it.

I’ve seen similar scarring in medical photographs from the period.

The pattern is distinctive, caused by iron cuffs worn for extended periods, sometimes years.

Rebecca nodded.

That’s what I thought.

But look at the rest of the photograph.

Look at how they’re standing together.

Marcus zoomed out to view the full image again.

He studied it carefully.

The proximity of the two men, their relaxed postures, the hints of smiles on their faces, the way they seemed comfortable in each other’s presence.

This is extraordinary, Marcus said.

The social codes in 1870 Charleston were still incredibly rigid even after emancipation.

White and black people didn’t just stand together like this for portraits unless there was a very specific reason.

And even then, the poses would typically reflect the power dynamic.

The white person seated while the black person stood or physical separation or the black person looking differential.

But not here, Rebecca said.

No, not here.

This looks like Marcus paused, searching for the right word.

Friendship.

Genuine friendship.

And in 1870, that would have been not just unusual, but potentially dangerous, especially in a city like Charleston, where white supremacist violence was already beginning to reassert itself.

He zoomed in on Thomas’ face, studying the features carefully.

The white man, Thomas, he’s well-dressed.

That suit is expensive, customtailored.

You can see the quality and how it fits his shoulders.

The way the fabric drapes, those brass buttons would have been costly.

And the cut of the jacket is fashionable for the period, but conservative, suggesting someone from an established family, probably old Charleston money.

Marcus continued his analysis, moving his attention to Samuel.

His clothing is different, simpler, but still respectable.

The cotton shirt is clean and well-maintained.

The vest is plain but neat.

He’s dressed well for the photograph, making an effort to present himself properly.

But there’s a clear economic difference between them.

He paused, his finger hovering over the image of Samuel’s scarred wrist.

But these scars tell us he was enslaved, probably for years, maybe since childhood.

The kind of scarring we’re seeing here doesn’t develop quickly.

It takes repeated prolonged wear of restraints, and the fact that it’s on both wrists suggests he might have tried to escape, or was considered a flight risk.

Rebecca felt a chill run through her.

She had known intellectually what the scars meant, but hearing Marcus articulate it so plainly brought the reality home.

Samuel had been a human being held in bondage.

His freedom stolen, his body marked by the instruments of his captivity.

“We need to find out who they were,” Marcus said, his voice taking on the determined tone Rebecca recognized from past research projects.

Real identities, family connections, what plantation Samuel was held on.

“If Thomas was from a wealthy Charleston family, there will be records, property deeds, tax documents, probate files, and if the family owned enslaved people, there might be plantation ledgers.

” Rebecca pulled out her notebook.

Where do we start? With white families who owned significant land holdings around Charleston in the 1860s, Marcus said, already pulling up databases on his laptop.

And we’re looking for families with sons named Thomas, who would have been around 20 to 25 years old in 1870.

Born between 1845 and 1850 roughly.

They worked in tandem, Rebecca searching through property records while Marcus combed through census data and tax records.

The Historical Preservation Society had extensive digital archives, and Marcus had access to the state genealological database through his professional credentials.

Together, they cast a wide net.

Thomas was one of the most popular names for boys in the South during that period.

Marcus noted as the list of potential candidates began to grow.

We could be looking at dozens, maybe hundreds of possibilities just in the Charleston area.

So, we narrow it down, Rebecca said.

Focus on families wealthy enough to afford custom tailoring and professional photography sessions.

cross reference with families who owned rice or cotton plantations since those required the largest enslaved populations.

They worked steadily through the morning, eliminating candidates one by one.

Too young, too poor, wrong location, no surviving records.

By lunchtime, they had narrowed the list to five strong possibilities.

By mid-afternoon, three remained, and one stood out as the most promising.

Thomas Whitfield, Marcus said, pulling up a detailed property record on his screen.

born 1848, which would make him 22 in April 1870.

Son of Robert Whitfield, who owned Riverside Plantation on the Ashley River, about 30 mi from Charleston.

The plantation encompassed 3,000 acres of rice fields.

Rebecca leaned over to read the screen.

How many enslaved people? Marcus scrolled down to the tax records from 1860.

218 according to this assessment.

That would have made Riverside one of the larger plantations in the area.

Rice plantations required enormous labor forces because of the brutal conditions.

Standing in water, the heat, the disease, the mortality rate was horrific.

218 people.

The number hit Rebecca like a physical blow.

218 human beings owned by one family.

Their labor stolen, their lives controlled completely by others, children born into slavery, families separated, generations lost to brutality and exploitation.

Is there a list of names? Rebecca asked quietly.

of the people who were enslaved there.

Marcus nodded.

Plantation owners kept records for tax and insurance purposes.

Let me search the Whitfield records.

He navigated through the digital archive, his fingers moving quickly across the keyboard.

Here, the Whitfield family papers were donated to the historical society in 1923.

They’ve been digitized.

He pulled up a scanned ledger from 1860.

The pages were yellowed and the handwriting was cramped, but the words were legible.

Each page listed names, ages, and work assignments.

Rebecca felt her throat tighten as she read the entries.

People reduced to line items in an account book, their entire existence summarized in a few words.

Now, they scanned through the pages methodically.

There were several people named Samuel.

Samuel, age 45, fieldworker.

Samuel, age 12, stablehand.

Samuel, age 8, kitchen helper.

Then on the fourth page, they found what they were looking for.

Samuel, age 16, house servant.

That would make him 26 in 1870.

Rebecca calculated quickly the right age for the man in the photograph.

Marcus made a note and continued searching through the records.

In subsequent ledgers from 1861 in 1862, they found more references to this Samuel.

He had remained in the main house working as a domestic servant rather than in the rice fields.

This was significant.

House servants typically had better living conditions than field workers, though they also lived under constant surveillance and were subject to the whims and violence of the enslaving family.

Then in a ledger from 1863, they found an entry that made them both stop.

Samuel House assigned to attend to Master Thomas.

“There it is,” Rebecca said, her voice barely above a whisper.

“Samuel was Thomas’s personal servant.

They knew each other, lived in the same house.

Samuel would have been 19.

Thomas would have been 15.

” Marcus sat back, processing this information.

So, we have a young enslaved man assigned to serve a teenage boy from the plantationowning family.

That’s the relationship during slavery.

But then seven years later, they’re standing together in a photography studio in Charleston, posing as what appears to be friends or equals.

Something happened between 1863 and 1870.

Rebecca said something that changed their relationship completely.

They needed to find out what happened after the war ended.

Marcus pulled up records from the reconstruction period, but this was always the most difficult research.

The years immediately following the Civil War were chaotic in South Carolina.

Sherman’s army had marched through in 1865, burning and destroying as they went.

Many records were lost, families scattered.

The entire social and economic structure of the state collapsed and had to be rebuilt.

But they found fragments.

Marcus discovered a notice in the Charleston Daily News from May 1865, just weeks after Lee’s surrender at Appamatics.

The notice listed Riverside Plantation among those offering wages to formerly enslaved people who would agree to stay and continue working the rice fields.

Many plantation owners tried this approach, attempting to maintain their agricultural operations with paid labor instead of slavery, though the wages offered were often barely enough to survive on.

There was no record of Samuel accepting such an offer.

His name didn’t appear on the payroll lists that survived in the Whitfield family papers.

Rebecca continued searching through property records while Marcus examined census data.

Then, in a property transaction from 1866, Rebecca found something that made her heart race.

Marcus, look at this,” she said, pulling up the document on her screen.

It was a deed of sale dated March 1866.

Thomas Whitfield had sold a portion of his inherited land, 50 acres on the southeastern edge of the Riverside plantation property, to a buyer listed as Samuel Freriedman.

Marcus leaned over to read the details, 50 acres, and the price.

He paused, recalculating to make sure he had read it correctly.

$50? That’s absurdly low.

Land prices were depressed after the war, but not that much.

50 acres would have been worth at least several hundred dollars, maybe more.

It wasn’t really a sale, Rebecca said, understanding flooding through her.

It was a gift.

Thomas gave Samuel the land, but structured it as a sale to make it legally binding and protect Samuel’s ownership.

They stared at each other across the desk, the implications settling over them like morning mist.

This wasn’t just a photograph of two men.

This was documentation of something profound.

Rebecca and Marcus spent the next several days piecing together more of the story.

They found Samuel in the 1870 census taken in June, just 2 months after the photograph was dated.

He was listed as living on his 50acre property.

His occupation recorded as farmer.

Living with him was a woman named Ruth, age 24, listed as his wife.

Thomas appeared in the same census, but in a different location.

He was living in Charleston proper, his occupation listed simply as clerk.

He had left the plantation, moved to the city, and taken a modest job in commerce.

no longer a plantation heir, but a working man earning wages like any other.

The contrast was striking.

Thomas had given up his inheritance, or at least a significant portion of it, to help Samuel, and both men had chosen new paths that diverged dramatically from what their births would have predicted.

But Rebecca knew they needed more than records and documents.

They needed to understand the human story, the motivations, and emotions that had led to that photograph.

She posted queries on several genealogy forums and historical research sites, asking if anyone had information about the Whitfield family or about a Freman named Samuel who had lived near Charleston in the 1870s.

She didn’t expect much.

These forums were often more noise than signal, and reliable information was rare.

But 3 days later, she received an email that changed everything.

The sender was a woman named Patricia Johnson who lived in Atlanta.

She explained that she was researching her family history and believed she was a direct descendant of a man named Samuel who had been enslaved on a rice plantation near Charleston.

She had seen Rebecca’s query and thought there might be a connection.

“My great great great-grandfather was Samuel,” Patricia wrote.

“Family stories say he was enslaved on a plantation called Riverside and that he gained his freedom with help from a white man who became his friend.

After the war, he bought land and started a farm.

We’ve preserved some family documents, letters, a Bible, some photographs.

I’d be happy to share them if they might help your research.

Rebecca’s hands were shaking as she typed her reply.

She explained about the photograph, about the marks on Samuel’s wrists, about the land transaction in 1866.

She asked if Patricia would be willing to meet and share the documents she had mentioned.

Patricia’s response came within an hour.

I can be in Charleston this weekend.

This is the story my family has been trying to piece together for generations.

Six months after discovering the photograph, Rebecca stood in a gallery at the Historical Preservation Society, watching visitors examine the image that had consumed her research and changed her understanding of what was possible even in the darkest periods of history.

The exhibition titled Brotherhood in Black and White, Samuel and Thomas, 1870, had drawn unexpected attention from across the country.

Historians, genealogologists, journalists, and descendants had traveled to Charleston to see the portrait and learn the story behind it.

The photograph was displayed in a climate controlled case, carefully lit to prevent further fading, while allowing visitors to see every detail.

Beside it, hung enlarged sections showing the scars on Samuel’s wrists.

Those permanent marks that had first caught Rebecca’s attention and set this entire investigation in motion.

The letters Samuel had written to Thomas were displayed nearby in protective cases, their faded ink still legible, their words still powerful after more than a century.

Property documents showed the land transaction, and a detailed timeline traced both men’s lives from enslavement and privilege through war, escape, and an unlikely friendship that defied every social convention of their era.

Patricia stood near the entrance with several members of her family, cousins, nieces, nephews, and her own children, who had traveled from across the South to see their ancestor honored, and his story finally told in full.

Several family members bore striking resemblances to Samuel.

The same strong features, the same steady gaze that looked out from the photograph with such dignity and self-possession.

One of Patricia’s grandsons, a college student studying history, stood transfixed before the photograph, seeing his own face reflected across five generations.

A steady stream of visitors moved through the exhibition, reading the text panels that explained the context of 1870 Charleston, the brutality of rice plantation slavery, the chaos of reconstruction, and the extraordinary courage it took for Thomas to help Samuel escape.

Many visitors stood for long minutes before the photograph itself, studying the faces of these two young men, trying to understand what had brought them to that studio, what had made them willing to risk social condemnation to document their friendship.

A reporter from the Charleston Post approached Rebecca, notebook in hand.

She was young, perhaps in her late 20s, and she had been following the story since Rebecca first announced the discovery.

Dr.

Martinez, she said, I’ve been covering this exhibition since it opened, and I keep hearing visitors say how surprised they are by this story.

What do you think is the most important lesson people should take from Samuel and Thomas? Rebecca considered the question carefully.

She had been asked variations of it dozens of times over the past months by journalists, by academic colleagues, by students, by visitors to the exhibition.

Each time she tried to find a way to express what this photograph and the story behind it meant, not just as historical artifact, but as evidence of human possibility.

I think, Rebecca said slowly, choosing her words with care.

It reminds us that history is not inevitable.

We often think of the past as fixed, as if everything happened the way it had to happen, as if the cruelty and injustice were simply the way things were and nothing could have been different.

But stories like this show us that individuals made choices.

Thomas chose to risk his inheritance, his family relationships, possibly his life, to help Samuel escape from slavery.

That was a choice, not an inevitability.

Samuel chose to maintain their friendship across all the barriers that society tried to erect between them.

to trust Thomas when trust must have seemed impossible.

Those were choices, too.

” The reporter nodded, scribbling notes.

“And what does that mean for us today?” “It means we have choices, too,” Rebecca replied.

“About what kind of world we want to build? About how we treat each other across lines of difference? About whether we’re willing to risk comfort and privilege to do what’s right.

” Thomas and Samuel showed that even in 1870, Charleston, in one of the most rigidly segregated societies in human history, genuine friendship and mutual respect were possible.

If it was possible then in those circumstances, then it’s certainly possible now.

The reporter thanked her and moved away to interview Patricia.

Rebecca stood alone for a moment, looking at the photograph that had started everything.

Thomas and Samuel stood shoulder-to-shoulder, frozen in silver and light, their faces showing those subtle hints of smiles that suggested shared understanding, shared secrets, shared hope for a different kind of future.

Patricia approached and stood beside Rebecca, both of them gazing at the portrait in companionable silence.

Finally, Patricia spoke.

My grandmother used to tell me that Samuel said the photograph was the most important thing he ever owned, besides his land and his family.

She said he kept it on the mantle until the day he died, and that sometimes he would just sit and look at it, remembering.

Remembering what? Rebecca asked gently.

“Remembering that friendship was possible?” Patricia said, “That a white man and a black man could see each other as brothers, could risk everything for each other, could build something together that transcended all the hatred and cruelty of their time.

” My grandmother said that whenever Samuel felt despair about the violence and injustice that came after reconstruction, whenever the world seemed to be sliding backward, he would look at that photograph and remember that he and Thomas had proven something important, that a different world was possible because they had lived it, even if only for a moment.

Rebecca felt tears prickling her eyes.

She thought about the care with which someone had wrapped this photograph in tissue paper and preserved it for over a century, about the family stories passed down through generations, about Patricia’s determination to research her ancestry and reclaim her family’s history.

All of it was an act of resistance against forgetting, against the eraser of stories that didn’t fit comfortable narratives.

Outside the gallery windows, Charleston continued its daily rhythm.

Tourist carriages clattered past on cobblestone streets.

Visitors photographed Antabellum mansions.

The city displayed its history selectively as it always had, emphasizing beauty while minimizing horror, celebrating heritage while obscuring the enslaved labor that built it all.

But here in this quiet gallery, Samuel and Thomas stood together as they had in April 1870.

The marks on Samuel’s wrists remained visible, a permanent reminder of the cruelty he had endured, the years stolen from him, the fundamental injustice of a system that treated human beings as property.

Those scars were part of the truth and could not be erased or ignored.

But beside those scars, captured forever in the photograph, was something else.

The hand of a friend who had chosen to see Samuel not as property, but as a human being deserving of freedom and dignity.

A friend who had risked everything to help him escape.

A friend who had given him land to build a new life.

A friend who had stood beside him in a photography studio and insisted that their bond be documented, preserved, remembered.

That too was part of the truth.

The scars and the friendship, the cruelty and the courage, the horror and the hope.

All of it woven together in one image, one story, one moment of connection that refused to be forgotten.

Rebecca took a deep breath and smiled at Patricia.

Thank you, she said quietly.

For preserving the letters, for keeping the memory alive, for trusting me with this story.

Thank you, Patricia replied, for finding it, for seeing what others might have missed, for making sure Samuel and Thomas are remembered not just as historical figures, but as human beings who chose love over hatred, courage over fear, friendship, over everything that tried to divide them.

They stood together a moment longer, then Patricia moved away to rejoin her family.

Rebecca remained watching as visitors continued to flow through the exhibition, pausing before the photograph, reading Samuel’s letters, learning about two young men who had defied their world, and in doing so had left behind proof that even in the darkest times, human decency and genuine connection could survive.

The afternoon light slanted through the gallery windows, illuminating the photograph just as afternoon light had illuminated it on Rebecca’s desk 6 months earlier.

Thomas and Samuel gazed out across the centuries.

News

🔥 Vatican Meltdown as “Pope Leo XIV” Allegedly Unseals a Forbidden Scroll Said to Rewrite Christ’s Final Words and Expose Centuries of Holy Silence — In a voice dripping with irony and suspense, insiders whisper that a newly crowned pontiff stared down trembling cardinals and hinted at a dust-choked parchment hidden since the crucifixion itself, a so-called final commandment rumored to demand compassion over power, shaking faith, egos, and vault doors while skeptics snarl and believers gasp, because nothing rattles Rome like the suggestion that heaven’s last memo was buried on purpose and now the walls are listening 👇

The Revelation of Pope Leo XIV: A Shocking Unveiling In the heart of the Vatican, a storm brewed beneath the…

This 1889 studio portrait looks elegant — until you notice what’s on the woman’s wrist

This 1889 studio portrait appears elegant until you notice what’s wrapped around the woman’s wrist. Dr.Sarah Bennett had spent 17…

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters—but then historians noticed their hands

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters, but then historians noticed their hands. The archive room of…

It was just a portrait of a soldier and his wife—until you notice what he’s holding

It was just a portrait of a soldier and his wife until you notice what he’s holding. The photograph arrived…

It was just a portrait of a mother — but her brooch hides a dark secret

It was just a portrait of a mother and her family, but look more closely at her brooch. The estate…

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920 — but pay attention to the groom’s hand

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920. But pay attention to the groom’s hand. The Maxwell estate…

End of content

No more pages to load