Why did experts turn pale when they zoomed into this portrait of two friends from 1888?

The digital archive room at the Charleston Heritage Museum felt unnaturally quiet on that October afternoon.

Dr.Emma Torres sat before three monitors, methodically scanning 19th century photographs from recently acquired estate collections.

Rain streaked the windows behind her, blurring the view of the historic district outside.

She had processed 47 images that day when she reached a portrait labeled simply two women, Charleston residents, 1888.

The photograph showed an elegant parlor with ornate wallpaper and heavy curtains framing a window.

Two young women sat side by side on an upholstered set, both wearing fashionable dresses of the late 1880s, high collars, fitted bodesses, elaborate sleeves.

The woman on the left appeared to be in her early 20s, white with light hair swept up in the Gibson girl style that would soon dominate the next decade.

Her dress was darker, possibly deep blue or burgundy, with delicate lace at the collar.

She sat with perfect posture, hands folded in her lap, her expression serene and confident.

The woman on the right was black, approximately the same age, wearing a lighter colored dress, perhaps gray or pale green, equally well-made and fashionable.

Her hair was styled similarly, pulled back elegantly.

She sat with her hands resting on her lap, but her posture seemed slightly more rigid, her smile more restrained.

Emma began the high resolution scan, noting the exceptional clarity of the original album in print.

Whoever had taken this photograph had been skilled.

The exposure was perfect, the focus sharp, the composition balanced.

As the digital image loaded, she could see remarkable detail.

The texture of the wallpaper, the reflection in a mirror barely visible in the background, the intricate beating on both dresses.

She zoomed in systematically, examining faces first.

Both women looked directly at the camera with the intense, unblinking gaze common in photographs requiring long exposures.

Then she moved to their clothing, noting the quality and style.

These were not working dresses, but formal attire, suggesting this was a special occasion.

When Emma zoomed in on the black woman’s hands, folded gracefully in her lap, her breath stopped.

There, on the left wrist, partially hidden by the sleeve, but visible in the high resolution scan, was a circular scar, unmistakable in its shape and origin.

Emma had seen similar marks in photographs of formerly enslaved people.

She knew exactly what caused scars like that.

Emma sat motionless, staring at the magnified image on her screen.

The scar was perhaps an inch wide, a band of lighter tissue circling the wrist like a bracelet.

The edges were distinct, the kind of permanent marking left by metal restraints worn over time.

She had cataloged photographs from plantation records before, had seen documentation of the brutalities of slavery.

But those images were always clearly labeled, contextualized, understood.

This photograph was different.

It showed two women sitting together in obvious comfort and equality, dressed similarly, posed as companions or even friends.

Yet, one bore the physical evidence of bondage.

Emma checked the acquisition records.

The photograph had come from the estate of Mrs.

Virginia Ashford, who had died 6 months earlier at age 93.

The estate donation included several boxes of family photographs, documents, and personal papers dating back to the 1780s.

This particular image had been in an album labeled family portraits, 1880 or 1900.

The notation listed no names, no identification of the subjects or the photographer, just a date.

1888.

Emma calculated quickly.

The 13th Amendment abolishing slavery had been ratified in December 1865.

This photograph was taken 23 years after emancipation.

The woman in the image would have been born around 1863 or 1864, possibly during the final years of the Civil War, possibly into slavery, possibly born free, depending on where and when exactly.

But that scar told a different story.

Those marks didn’t form from a single incident.

They developed over time from iron shackles or manicles worn repeatedly.

Even if this woman had been born free, she had been restrained at some point in her life.

Emma zoomed out to look at both women again.

Their proximity on the seti, the similar quality of their clothing, the domestic setting.

Everything suggested intimacy, familiarity, perhaps even affection.

This wasn’t a photograph of mistress and servant posed formally with clear hierarchical distance.

They sat close together, almost touching.

What was the relationship between these two women? Why were they photographed together in this way? And why had no one in 136 years apparently noticed or questioned the scar visible on one woman’s wrist? Emma saved multiple highresolution captures of the image and began drafting an email to Dr.

Marcus Webb, a colleague who specialized in post civil war African-American history in the South.

She needed expertise beyond her own.

This photograph held secrets that demanded investigation.

Dr.

Marcus Webb arrived at the museum the next morning, his usual energetic demeanor subdued after Emma had sent him the photographs overnight.

They met in the conservation lab where Emma had the image displayed across a large monitor, the magnified section showing the wrist scar clearly visible.

Marcus leaned close, studying the detail silently for nearly a minute before speaking.

Charleston, 1888.

Do we have any providence beyond the estate donation? Emma spread out the acquisition paperwork.

The Ashford family.

They’ve been in Charleston since before the Revolution.

The estate included extensive documentation, land deeds, business records, personal correspondence.

I haven’t gone through most of it yet.

I only noticed this photograph yesterday.

Marcus nodded slowly, his eyes never leaving the image.

That scar is definitely from shackles or manicles.

See the uniform width? The way it circles completely.

That’s consistent with iron restraints.

Probably worn over an extended period during childhood or adolescence when the bones were still growing.

But this is 1888, Emma said, 23 years after abolition.

Legally, yes.

But, you know, the reality was far more complex.

Marcus pulled up a chair, settling in for what Emma recognized as one of his impromptu history lectures, always thorough, always illuminating.

After the Civil War, many formerly enslaved people remained on the same plantations and in the same households where they had been held in bondage.

Sometimes by choice because they had nowhere else to go, no resources, no alternatives.

Sometimes because of debt p&age, sharecropping arrangements, or outright coercion.

He gestured to the photograph.

Look at this setting.

This is an upper class Charleston home, probably in the historic district.

The furnishings, the wallpaper, the quality of light from those windows.

This is wealth.

old wealth most likely.

Emma saw what he meant.

Every detail of the room visible in the photograph spoke of privilege and status.

The carved wooden furniture, the elaborate curtains, the decorative objects barely visible on a side table.

Now look at these two women, Marcus continued.

Similar ages dressed in comparable quality clothing sitting together in what appears to be companionable proximity.

This isn’t a typical employer servant photograph of the era.

Those would show clear spatial and postural hierarchy.

This is something else.

What are you thinking?” Emma asked.

Marcus zoomed in on both faces, examining them carefully.

“I’m thinking we need to find out who these women were and how they were related.

Because they were related somehow, I’d stake my reputation on it.

The question is whether that relationship was chosen or imposed, loving or exploitative, or most likely some complicated mixture of both.

” Emma spent the next 3 days systematically working through the Ashford estate papers while Marcus searched historical databases and census records.

The family’s documentation was extensive but chaotic.

Generations of letters, receipts, legal documents, and personal papers stored in no particular order.

She found plantation records from the 1850s, listing enslaved people by first name only.

Their ages, skills, and monetary values recorded with the same clinical detachment used for livestock.

The lists made her stomach turn.

Lucy, age 24, house servant, $800.

James, age 19, blacksmith, $200.

Sarah, age 16, seamstress, $700.

Then she found a leatherbound journal dated 1863 1865, kept by someone named Ellaner Ashford.

The handwriting was elegant.

The entries initially focused on mundane domestic matters and social calls.

But as Emma read chronologically, the tone shifted dramatically with entries from 1864.

June 12th, 1864.

Father has taken ill again.

Dr.

Morrison says the consumption worsens.

He speaks of matters he wishes settled before, but I cannot bear to write it.

He has confessed something to me that I scarcely know how to comprehend or accept.

Emma’s pulse quickened.

She read on.

June 15th, 1864.

I have met her.

Father insisted, though mother would not come downstairs.

Her name is Clara.

She is a year younger than I, born in this very house to one of our I cannot write the word.

Father says she is my sister, halfsister.

He says he has provided for her care.

that certain arrangements must continue after his death.

Mother will not speak of it.

” Emma sat back, her mind racing.

She photographed the pages and continued reading.

July 3rd, 1864.

Clara remains in the house.

We take meals separately, live in different wings, but I find myself seeking her out.

She is intelligent, well spoken.

Father has seen to her education, it seems, in ways that were hidden from mother and me.

There is a strangeness in speaking to someone who shares my blood but has lived such a different life under this same roof.

Emma grabbed her phone and called Marcus immediately.

I found something.

The Ashford family.

There were two daughters, Elellanor, the legitimate white daughter, and Clara, the mixed race daughter born to an enslaved woman.

They lived in the same house.

Marcus’ response was immediate.

Get me everything you can find about both of them.

Birth records, death records, any photographs, any mention in family correspondence.

This is the connection.

Marcus arrived with census records and city directory listings spread across his laptop.

I found them both.

Elellanar Ashford appears in the 1870 census as daughter of Robert and Margaret Ashford, age 26, living in the family home on Meeting Street.

And here in the same household, Clara Ashford, listed as domestic servant, age 25, race marked as mulatto in the census terminology of the time.

Emma pulled up more journal entries from Ellanar’s diaries.

These from 1865.

April 20th, 1865.

The war has ended.

Father died 3 months ago.

And now this news.

Everything has changed.

Yet nothing has changed.

Clara is legally free now.

But where would she go? This house is the only home she has known.

Mother insists she remain as paid household help.

The distinction seems meaningless to me.

She’s still here, still serving, still trapped by circumstances beyond her choosing.

The entries painted a complex picture.

Elellanar seemed genuinely conflicted about her halfsister’s situation.

Aware of the injustice, yet unable or unwilling to fundamentally change the arrangement, Clara appeared in the margins of Elellanar’s writing, teaching Elellanar to sew fine stitches, nursing her through an illness, sitting with her during their mother’s final days in 1872.

May 14th, 1872.

Mother is buried.

Clara and I are alone now in this house.

Two sisters divided by everything society deems important.

We maintain the fiction that she is my employee.

But in truth, we are simply two women living together, bound by blood and circumstance.

I pay her wages, yes, but they are wages she cannot easily refuse.

Wages that keep her here, serving me as she once served under bondage.

Emma found financial records showing regular payments to Clara Ashford beginning in 1866.

Modest wages for domestic work.

But she also found something else.

a deed from 1880 transferring ownership of a small property on the outskirts of Charleston from Elellaner to Clara.

The transaction was recorded legally, but included a handwritten note given freely to my sister that she might have security independent of my household.

Marcus examined the deed carefully.

This is unusual.

White women transferring property to black women in 1880s Charleston.

That would have raised eyebrows.

The fact that she’s identified as my sister in the note is extraordinary, acknowledging that relationship in legal documentation.

“So Eleanor was trying to help Clara?” Emma asked.

“Maybe, or maybe trying to assuage her own guilt, or both.

” Marcus pulled up another document.

“Look at this.

Clara is listed in the 1880 census as still living at the Asheford residence, even though she owned property elsewhere.

She stayed even when she had the legal right and financial means to leave.

Emma found the answer in a letter dated March 1888, tucked into Ellaner’s correspondence file.

It was addressed to a photographer named William Barnett, whose studio had been located on King Street in Charleston.

Mr.

Barnett, I wish to commission a portrait photograph to be taken at my residence.

The subjects will be myself and my sister Clara.

I understand this may be an unusual request given the current social climate, but I am willing to pay double your standard rate for your discretion and professionalism.

The photograph is for private family purposes and will not be publicly displayed.

Please advise your availability.

Ellanar Ashford.

Marcus read the letter over Emma’s shoulder.

She wanted documentation of their relationship, something private, just for them.

Emma found Barnett’s reply, dated a week later.

Miss Ashford, I am honored by your request and require no additional payment beyond my standard portrait fee.

I have known your family for many years and understand the delicate nature of this commission.

I’m available Tuesday, March 27th at 2:00.

I will bring my equipment to your residence and ensure complete privacy during the session.

William Barnett.

The date matched.

March 27th, 1888.

The notation on the photograph’s original mounting, barely visible in the scan.

Emma pulled up Elanor’s journal entries from that period.

March 27th, 1888.

Today, we sat for a portrait, Clare and I, together as we have lived these past 24 years since mother’s death.

I wanted something to acknowledge what we are to each other.

Even if the world can never know.

Clara was hesitant at first, concerned about the propriety, but I insisted we are sisters.

Whatever else divides us, that truth remains.

March 28th, 1888.

Mr.

Barnett brought the wet plate proof today.

Clara looked at it for a long time without speaking.

We look like equals in this, she finally said.

I told her we should be equals, that the accident of birth and circumstance that made our lives so different is an injustice I have never known how to remedy.

She touched my hand and said, “You have done what you could, Ellaner.

That is more than most would do.

But is it enough? Can it ever be enough?” Emma felt tears prickling her eyes.

This wasn’t a simple story of exploitation or a simple story of sisterly love.

It was both, neither.

Something far more complicated.

Marcus pointed to the screen.

The scar.

Did Ellaner know about it? Did she understand what it meant? Emma searched through more entries and found it.

January 1866.

I saw Clara’s wrists today when she reached for something high on a shelf.

The scars there, I knew what they were, though I had never seen them clearly before.

Evidence of what was done to her before the war ended, before freedom came.

I wanted to ask, wanted to understand, but the words would not come.

How does one ask one sister about the chains she wore? Emma contacted Dr.

Patricia Coleman, a specialist in the material culture of slavery at the University of South Carolina.

Dr.

Coleman arrived the following week, bringing with her extensive documentation of restraint devices used in the antibbellum and civil war periods.

Shackles and manacles left very specific scarring patterns, Dr.

Coleman explained, examining the magnified image of Clara’s wrist.

The circular formation, the uniform width, the slight indentation of tissue, these are consistent with iron manicles likely worn during adolescence.

The scar tissue suggests they were worn over an extended period, not just once or occasionally.

Emma had found more fragments in Ellaner’s journals.

March 1864.

Father explained to me that Clara, though she is his daughter, could not be acknowledged as such during the years of slavery.

She was listed in his property records as belonging to mother, legally enslaved despite her paternity.

He says he kept her in the house, had her educated secretly, but there were times when appearances had to be maintained, when his overseer or business associates visited, times when Clara had to be, I cannot bear to write it clearly, restrained like any other enslaved person to maintain the fiction.

Dr.

Coleman’s expression was grim.

This was not uncommon in situations involving enslaved people who were blood relatives of their enslavers.

The cognitive dissonance was profound.

They might be treated with relative favor in private, educated, given better clothing and housing, but still subjected to the apparatus of bondage when necessary to maintain social appearances or control.

So Clara was shackled even though she was his daughter? Emma asked.

Exactly.

The legal system recognized no familial relationship between enslaved people and their enslavers, even when paternity was obvious and acknowledged privately.

Clara would have been property in the eyes of the law until 1865, regardless of her father’s feelings or private arrangements.

Marcus had been quietly reviewing documents.

I found something else.

Robert Ashford’s will, dated November 1864, 2 months before he died.

He made specific provisions for Clara.

She was to be freed immediately upon his death, given a sum of money, and Elellanor was instructed to provide for her continued residence and well-being as befit her station as a member of this family.

But he didn’t free her while he was alive, Emma asked.

No, the will suggests he was afraid of social repercussions of what acknowledging her would mean for Eleanor’s reputation and marriage prospects.

So Clara remained enslaved, wearing those manacles when necessary until his death freed her legally in January 1865, just months before the war ended and emancipation came to everyone.

Dr.

Coleman pointed to the photograph again.

And look at how she’s positioned her hands in this portrait.

They’re visible, resting in her lap, the scarred wrist partially showing.

That’s a choice.

She could have hidden her hands in the folds of her dress, positioned her arms differently.

She chose to let this evidence remain visible.

Emma understood.

The photograph was documentation, testimony, witness.

Marcus had traced Clara’s life through city directories, tax records, and church registries.

She stayed with Eleanor until 1895, 7 years after this photograph was taken.

She finally moved to the property Elellanor had deeded to her.

She lived there alone until her death in 1903.

Emma found Ellaner’s journal entries from 1895.

September 15th, 1895.

Clara is leaving.

After 31 years of living under this roof, first as enslaved, then as employee, always as my sister, she is taking residence in her own home.

I should be happy for her independence, yet I feel the loss profoundly.

We have been each other’s constant companion through everything.

September 20th, 1895.

I helped Clara move her belongings today.

So few possessions after a lifetime, but she has her books, her sewing things, her freedom.

She embraced me before leaving and said, “You gave me what you could, Ellanar.

I understand that now.

We were both trapped by the world we were born into.

I wanted to argue, to say I could have done more, should have done more.

But perhaps she’s right.

Perhaps we both did what we could within the confines that bound us.

” Emma found records of Clara’s property, a modest house on 3 acres, which she cultivated into a productive garden.

Tax records showed she supported herself through seamstress work listed in city directories from 1896 1902 as Clara Ashford dress maker.

But Emma also found evidence of continued connection between the sisters.

Ellaner’s household account books showed regular payments to C.

Ashford for sewing services, far more than would have been necessary for one woman’s wardrobe.

Letters between them survived, formal in tone, but revealing underlying affection.

Dear Ellaner, thank you for the commission for Mrs.

Harrison’s trusoe.

The work keeps my hands busy and my mind occupied.

I trust you are well and that the spring rains have not flooded your garden as they have mine.

Your sister Clara, dearest Clara, I am sending additional fabric and thread.

Please make yourself a new dress for church.

Something in the green that suits your complexion so well.

Consider it compensation for the Truso work, though we both know I’m overpaying as usual.

I miss our evening conversations.

Your sister, Ellaner.

Marcus found Clara’s death certificate from April 1903.

Cause of death? pneumonia, age 64.

The informant listed was Elellanar Ashford, who had been present at her sister’s death.

Ellaner’s journal from that period, April 8th, 1903.

Clara is gone.

I held her hand as she passed.

Those scarred hands that had worked so hard, endured so much.

She said at the end, “We were sisters, Ellaner.

Whatever else was true, that was always true.

” Yes, sisters.

Uh, bound by blood and history and all the complicated truths we lived with.

Emma traced how the photograph had remained in the family for over a century.

Elellanar had no children.

When she died in 1911, her estate passed to her nephew, Robert’s son, from a brief early marriage that had ended in his wife’s death.

The nephew, also named Robert, inherited the house and all its contents, including Ellaner’s private papers and photographs.

Through generations, the image had been preserved in family albums, its significance gradually forgotten.

By the time it reached Virginia Asheford in the mid- 20th century, it was simply an old family photograph with no names attached, no story preserved.

Emma contacted Virginia Asheford’s granddaughter, Rebecca, now living in Atlanta.

Rebecca agreed to visit the museum and was visibly shaken when she saw the enlarged image and read the research Emma had compiled.

“I never knew,” Rebecca said quietly, staring at Clara’s face in the portrait.

“My grandmother had boxes of old family things, but she never talked about this period of our history.

I don’t think she knew the full story herself.

Emma showed her Elanor’s journals, the letters between the sisters, the deed transferring property to Clara.

Rebecca read silently, tears streaming down her face.

They were sisters, she finally said.

Real sisters who cared for each other, but trapped in a system that made their relationship impossible to acknowledge publicly.

And Clara wore those scars her whole life, physical evidence of what had been done to her.

“Your family’s story is more complex than simple villain,” Marcus said gently.

Elellanar was complicit in a system of oppression, yes, but she also tried within the severe limitations of her time and place to honor her relationship with Clara.

That doesn’t excuse anything, but it does make the history more human, more real.

Rebecca looked at the photograph again.

What will you do with this? How will you tell this story? Emma had been thinking about that question for weeks.

We want to create an exhibition that honors both women, that doesn’t simplify their relationship into either pure exploitation or pure affection, but shows the complicated reality of how slavery and its aftermath shaped families and lives.

Clara deserves to be remembered not just as a victim, but as a full person who navigated impossible circumstances with dignity.

And Elellanar deserves to be understood as someone who was both privileged by an unjust system and in her limited way tried to resist it.

Rebecca nodded slowly.

Yes, tell the whole truth.

That’s what they both deserve.

Four months later, the Charleston Heritage Museum opened an exhibition titled Sisters in Blood and Bondage, the Asheford Family Portrait.

The centerpiece was the 1888 photograph displayed with extensive contextual documentation that Emma and Marcus had compiled.

The wall text began in March 1888.

Two women sat together for a portrait in a Charleston home.

They were sisters, Ellaner Ashford and Clara Ashford, connected by blood through their father, Robert Ashford, separated by everything else that 19th century southern society deemed important.

This photograph documents their relationship 23 years after slavery’s legal end, but it also documents how the legacy of bondage persisted in intimate spaces and complicated relationships.

The exhibition didn’t shy away from difficult truths.

A panel explained Clara’s status before 1865.

Clara was born around 1863 or 1864 to an enslaved woman named Sarah and Robert Ashford, a wealthy Charleston merchant.

Despite being his biological daughter, Clara was legally considered property, listed in household inventories, and subjected to the full apparatus of slavery, including physical restraint.

Beside the main portrait, Emma had displayed the magnified image showing Clara’s wrist scar with an explanation.

This circular scar visible on Clara’s left wrist is consistent with iron manicles used to restrain enslaved people.

Such scars formed over time from repeated use of shackles typically during adolescence.

The Clara chose to position her hands visibly in this portrait, allowing this evidence to remain in the frame suggests the photograph held meaning beyond simple documentation.

It was testimony.

Elellanar’s journal entries were displayed in careful selection, showing the complexity of her feelings, her acknowledgement of injustice, her limited attempts at remedy, her genuine affection for Clara, and her inability to fully break with the social system that privileged her.

Clara’s own voice appeared through the few letters that survived, dignified and reserved, claiming her identity, your sister, Clara.

The exhibition traced both women’s lives after the photograph, Clara’s eventual move to independence, Ellaner’s continued support, their ongoing relationship until Clara’s death.

It ended with Rebecca’s statement.

My family’s history includes both perpetrators and victims of slavery.

Sometimes in the same photograph, sometimes in the same bloodline.

Acknowledging this complexity is painful but necessary.

Clara Ashford was my ancestor as much as Ellanar was.

Her story deserves to be told.

On opening day, a diverse crowd filled the gallery.

Emma watched as visitors stood before the portrait, reading the extensive documentation, many with tears in their eyes.

She overheard conversations, people discussing their own family histories, the complicated legacies they carried, the truths they were still uncovering.

An elderly black woman stood before Clara’s image for a long time before speaking to her companion.

She’s looking right at us right through time, saying, “This happened.

Remember this happened.

” That scar on her wrist is her testimony.

Emma felt the weight of that observation.

Clara had indeed left testimony in the scar she chose not to hide.

In the photograph she agreed to sit for, in the dignity with which she posed beside her halfsister despite everything that divided them.

The photograph would remain in the museum’s permanent collection, no longer anonymous, but fully contextualized, telling a story that was specific to two women in Charleston in 1888, but also emblematic of countless untold stories about how slavery shaped families, relationships, and lives long after its legal end.

As the exhibition continued into the evening, Emma stood beside Marcus, both of them watching visitors engage with the story they had uncovered.

“Do you think we did right by them?” Emma asked quietly.

“By both of them?” Marcus considered the question.

“We told the truth as fully as we could recover it.

We showed Clara as a person, not just a victim.

We showed Eleanor’s complicity in her conscience.

We didn’t simplify or sanitize.

Yes, I think we honored them both.

” The museum lights gleamed on the glass, protecting the 136-year-old photograph.

Elellanar and Clara sat side by side in perpetuity, two sisters bound by blood and separated by history.

Their complicated truth finally fully

News

🍔 GOLDEN STATE SHOCKER — CALIFORNIA GOVERNOR IN FULL-BLOWN CRISIS AFTER IN-N-OUT’S SECRET EXIT PLAN LEAKS, INSIDERS WHISER “THEY’RE PACKING UP” 🚨 The narrator sneers as late-night boardroom memos surface, fryers go cold, and stunned employees watch rumors spread like wildfire, turning a beloved burger chain into the unlikely spark of a political meltdown that has Sacramento sweating bullets 👇

The Hidden Collapse: A Hollywood Tale of California’s Economic Crisis In-N-Out Burger had always been a symbol of California’s vibrant…

🚛 HIGHWAY CHAOS — TRUCKERS’ REVOLT PARALYZES EVERY LAND ROUTE, KHAMENEI SCRAMBLES TO CONTAIN THE FURY 🌪️ The narrator’s voice drops to a biting whisper as convoys snake through empty highways, fuel depots go silent, and leaders in Tehran realize this isn’t just a protest — it’s a nationwide blockade that could topple power and ignite panic across the region 👇

The Reckoning of the Highways: A Nation on the Edge In the heart of Tehran, the air was thick with…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Darkened City: A Night of Reckoning In the heart of Moscow, a city that once stood proud and unyielding,…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Shocking Resurrection: A Hollywood Revelation In a world where faith intertwines with fame, the announcement sent ripples through the…

🎬 “TO THIS DAY, NO ONE CAN EXPLAIN IT” — JIM CAVIEZEL BREAKS YEARS OF SILENCE ABOUT THE MYSTERY THAT HAUNTED HIM AFTER FILMING ⚡ In a hushed, almost trembling confession, the actor leans back and stares past the lights, hinting at strange accidents, eerie coincidences, and moments on set that felt less like cinema and more like something watching from the shadows, leaving even hardened crew members shaken to their core 👇

The Unseen Shadows: Jim Caviezel’s Revelation In the dim light of a secluded room, Jim Caviezel sat across from the…

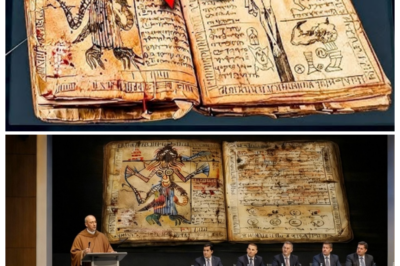

📜 SEALED FOR CENTURIES — ETHIOPIAN MONKS FINALLY RELEASE A TRANSLATED RESURRECTION PASSAGE, AND SCHOLARS SAY “NOTHING WILL BE THE SAME” ⛪ The narrator’s voice drops to a breathless whisper as ancient parchment cracks open under candlelight, hooded figures guard the doors, and words once locked inside stone monasteries spill out, threatening to shake faith, history, and everything believers thought they understood 👇

The Unveiling of Truth: A Resurrection of Belief In the heart of Ethiopia, where the ancient echoes of faith intertwine…

End of content

No more pages to load