When historians examined this 1860 portrait closely, they discovered an impossible secret.

Dr.Sarah Morrison had examined thousands of Civil War era photographs in her 20-year career at the Smithsonian.

But nothing prepared her for what arrived on a cold January morning in 2019.

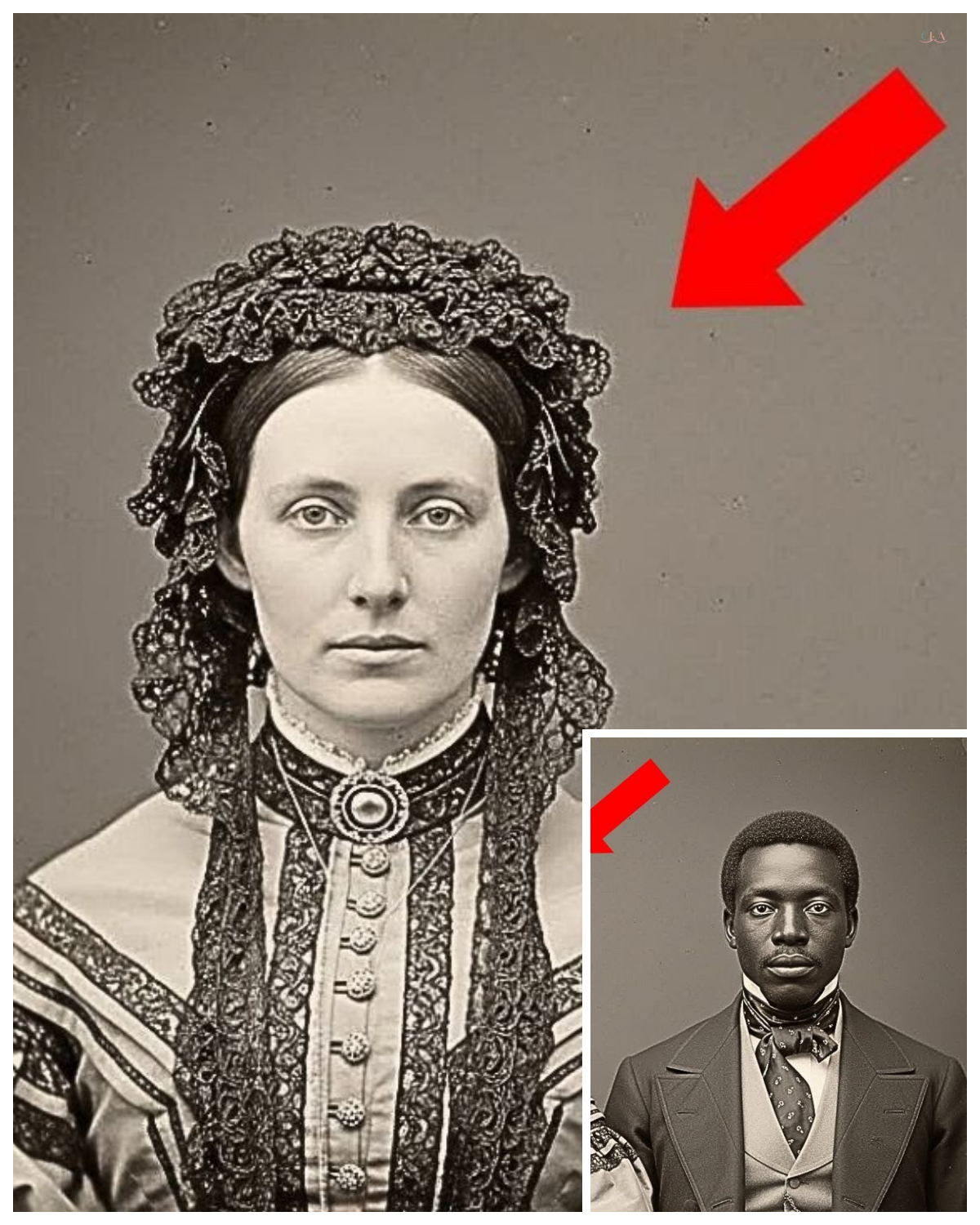

A small photograph in a worn leather case donated anonymously with only a brief note saying 1860 Philadelphia showed two people posed in an elegant photography studio.

a woman in an exquisite Victorian gown adorned with intricate lace and a magnificent brooch and a man in a perfectly tailored suit with silk details.

At first glance, it seemed like just another portrait from the turbulent years before the Civil War.

But something made Sarah pause as she lifted the image toward the light.

The photograph was too formal, too expensive for ordinary people of that era.

Studio portraits in 1860 cost a small fortune, equivalent to several months wages for working-class Americans.

The woman’s dress alone featured layers of imported French lace, handstitched beadwork, and an ornate brooch at her throat that caught the light with an almost deliberate brilliance.

The man’s suit was customtailored with silk crevat and details that spoke of wealth and refined taste.

But more than the clothing, it was their bearing, the dignity in their posture, the directness of their gaze that seemed to challenge anyone who looked at them.

Sarah placed the photograph under her magnifying lamp, adjusting the angle to catch the light just right.

her breath caught in her throat.

There, barely visible in the lower right corner of the image, was a small symbol she’d seen only twice before in her entire career, a tiny quilted pattern etched into the photographers’s studio mark, a coded signature.

Her hands began to tremble as she reached for her reference books.

This wasn’t just any portrait.

This was evidence of something that had been illegal, dangerous, and systematically erased from American history books for over a century.

She grabbed her phone and called Dr.

from Marcus Hayes, a specialist in abolition era documentation at Harvard University.

Marcus, I need you to see something immediately.

Can you catch the next train to Washington? Sarah, I’m in the middle of preparing my spring lectures.

It’s a craft photograph from 1860, 2 years after they wrote their memoir.

Silence stretched across the line, then barely above a whisper.

You’re certain the studio mark matches James Bington’s coded signature.

Marcus, if this is authentic, it’s only the second confirmed photograph of them together ever found.

I’ll be there in 4 hours.

” Sarah sat back in her chair, her heart racing as she stared at the two faces frozen in time.

The woman’s eyes held a hint of defiance beneath her calm exterior, while the man’s posture radiated quiet strength and protective watchfulness.

They looked like wealthy socialites, the kind of people who would attend theater performances and literary salons in Philadelphia’s high society.

But that was exactly the point.

That was exactly what had made their story so dangerous and why this photograph had been forbidden in American schools for generations.

When Dr.

Marcus Hayes arrived at the Smithsonian that evening, he didn’t bother with pleasantries or small talk.

Sarah led him directly to the conservation laboratory where the photograph lay protected under archival glass, illuminated by carefully controlled lighting.

Marcus approached slowly, almost reverently, as if the image might vanish if he moved too quickly.

He leaned in close, his experienced eyes scanning every detail of the photograph.

Then he saw the studio mark and his face went pale.

“My god,” he whispered, his voice barely audible.

“Sarah, this is real.

This is actually real.

” Sarah pulled up reference images on her tablet, comparing them side by side with the photograph.

James Bington operated a studio in Philadelphia between 1855 and 1863.

He was a Quaker abolitionist who secretly documented freedom seekers who reached the north.

The quilted square pattern was his way of marking photographs that were part of the network, a signal to others who knew what to look for.

Marcus straightened, running his hand through his graying hair, a habit he’d developed during decades of archival research.

Um, only 17 of his photographs are known to exist in collections worldwide.

Most were deliberately destroyed because they could be used as evidence by slave catchers, even after the Civil War started.

Bington himself burned his studio records in 1863 when Confederate sympathizers in Philadelphia threatened his family.

The story of William and Ellen was legendary among historians who specialized in the Underground Railroad and resistance movements during slavery.

But physical evidence of their lives after reaching freedom remained frustratingly scarce.

In December 1848, they had accomplished what seemed impossible at the time.

Escaping from Georgia bondage by traveling publicly and openly through the heart of the South, staying in hotels, eating in restaurants, riding first class train cars, all in plain sight of slave catchers, authorities, and suspicious travelers.

Ellen had disguised herself as a wealthy, ailing white gentleman traveling north for urgent medical treatment.

William had posed as his faithful and attentive servant.

The ruse was brilliant, audacious, and terrifying.

One suspicious glance, one wrong word, one moment of nervousness, and they would have been captured, separated forever, and likely sold to the brutal cotton plantations of the deep south as punishment for attempting escape.

“Uh, to look at her dress in this photograph,” Sarah said, pointing to the elaborate gown that Ellen wore.

“This was taken in 1860, 12 years after their escape.

She’s wearing exactly the kind of expensive, fashionable clothing she could never have worn as an enslaved person.

This photograph is an act of defiance, a public declaration.

Marcus nodded slowly, historian’s mind already racing through implications and questions.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made photographs like this incredibly dangerous, even in the North.

Slave Catchers could use them to identify freedom seekers and legally recapture them, dragging them back to bondage.

That’s why so few portraits exist from this period.

It was simply too risky to be photographed.

Which raises the critical question, Sarah said quietly, her eyes fixed on Ellen’s face in the image.

Why did they take this enormous risk? Why commission such a formal, expensive, and public portrait when it could literally be used as evidence to destroy their freedom? For three intensive days, Sarah and Marcus worked almost without rest in the conservation laboratory, using every technological tool available to analyze the 1860 photograph without causing any damage to its delicate surface.

They photographed it under different wavelengths of light, ultraviolet, infrared, raking light, examined it with digital microscopy at extreme magnifications, and compared every visible detail against known images from the period.

On the fourth morning, exhausted but persistent, Sarah made the discovery that would transform their understanding of the entire escape and its aftermath, she was examining an ultra- highresolution digital scan of the photograph on her computer, systematically zooming in on different sections, documenting every detail for their research archive.

When she focused on the ornate brooch at Ellen’s throat, the piece of jewelry that had caught her attention from the very beginning, she noticed something that made her freeze.

Under extreme magnification, the brooch revealed itself as far more than decorative jewelry.

There was text engraved on its surface, impossibly small letters, deliberately hidden within the intricate metal work and decorative flourishes.

The engraving had been done by a master craftsman, someone who understood how to conceal information in plain sight.

“Marcus,” she called out, her voice tight with barely controlled excitement.

“You need to see this immediately.

” He crossed the laboratory quickly, nearly knocking over his coffee in his haste.

Leaning over her shoulder to see the computer screen, his eyes widened as Sarah isolated and digitally enhanced the image of the brooch.

The enhancement revealed words etched in microscopic script around the brooch’s ornate border.

Liberty or death.

EC1 1848.

EC.

Marcus breathed, his voice filled with wonder.

Ellen.

She’s literally signing the photograph with her initials in the year of their escape.

This is a personal statement, a claim of identity and freedom.

But there was more.

Much more.

In the center of the brooch, barely visible even under extreme digital magnification, was a tiny but remarkably detailed map.

It showed a simplified but precise representation of the route from Georgia to Philadelphia with specific stops marked along the way using tiny symbols that would mean nothing to a casual observer.

Sarah felt her pulse quicken as she began identifying locations.

Marcus, this isn’t just a portrait or even just a political statement.

It’s a coded historical document.

She’s literally wearing evidence of their entire escape route around her neck.

Marcus grabbed his research notebook, his hands shaking slightly with excitement as he began sketching and annotating what they were seeing.

Do you understand what this means? Historians have debated their exact route for over 170 years.

We knew the major cities, Savannah, Charleston, Richmond, Baltimore, Philadelphia, but we never knew the specific stops between those cities, the safe houses, the people who risked everything to help them.

And she wore the evidence in a formal photograph, Sarah said softly, almost in disbelief, where anyone could have seen it if they looked carefully enough.

It’s as if she wanted the truth to survive somehow, to be discovered by someone who cared enough to look deeply.

The mysterious location marked on Ellen’s brooch was a small city called Mon, Georgia, less than 100 miles from where their desperate escape had originally begun in 1848.

Marcus spread detailed Annabella maps across the large research table in the archive room, trying to understand the logic and reasoning behind why two freedom seekers would risk marking this particular location on their coded jewelry.

“It makes absolutely no sense from a strategic perspective,” he muttered, circling Makin repeatedly on the historical map with a red marker.

“They escaped from Mon originally, fleeing the very place where they had been enslaved.

” “Why would Ellen mark it on the brooch as a significant stop on their journey to freedom? Why commemorate the place of their bondage? Sarah pulled up detailed census records from 1848 on her laptop, cross referencing names, occupations, and addresses.

Let me search for something specific.

If they stopped there, or if that location had significance, maybe there was a contact, a helper, someone working underground that historians have never identified or documented.

As she scrolled methodically through pages of names, occupations, and property records, a subtle but distinct pattern began to emerge from the data.

Min had maintained a small but surprisingly notable free black community throughout the 1840s, including several skilled craftsman, a blacksmith, two preachers, and several merchants who operated legitimate businesses.

But one name in particular caught Sarah’s trained attention, a seamstress and businesswoman named Ruth, who ran an established dress shop that catered exclusively to wealthy white women throughout central Georgia.

Marcus, look at this record carefully.

A Sarah turned her laptop screen toward him, highlighting specific entries.

Ruth operated one of the most successful and respected dressmaking establishments in central Georgia from 1842 onward.

According to these business records and tax documents, she employed at least four people at any given time and frequently traveled to Charleston, Savannah, and even as far as Richmond to purchase expensive fabrics, imported laces, and fashion materials.

Marcus’ eyes widened with sudden understanding.

A perfectly legitimate business that required regular documented travel throughout the South.

the absolutely perfect cover for underground railroad activities.

She could move freely, carry materials, gather information, and no one would question her presence because she had a documented business reason to be traveling.

They spent the next several hours digging deeper into Ruth’s business records.

What they discovered was remarkable.

Ruth had been freed by her former enslavers detailed will in 1842.

An unusual circumstance that gave her not only legal freedom, but also a small monetary inheritance, just enough to start her dressmaking business and establish herself as an independent businesswoman.

But what truly fascinated Sarah was a specific notation she found in a merchant’s detailed ledger from December 1848.

A large unusual order of men’s formal clothing, including expensive suits, travel accessories, bandages, and medical supplies purchased from Ruth’s shop just 5 days before William and Ellen’s documented and daring escape.

“She made the disguise,” Sarah said slowly, the pieces finally falling into perfect place.

“The entire transformation, Ellen’s suit, the bandages, the props, every detail.

Ruth created all of it.

” Grace arrived at the Smithsonian 3 days later, a elderly woman in her 70s carrying a worn leather bag that seemed to hold more than just documents.

It carried the weight of generations of carefully guarded secrets.

She had called ahead, asking specifically and urgently for Dr.

Morrison, saying only that she had information about the craft photograph and the woman who made their freedom possible.

Now she sat across from Sarah and Marcus in the archives private research room.

The space quiet except for the soft hum of climate control systems protecting precious historical materials.

From her bag, Grace carefully removed a Bible.

Its leather cover cracked and worn with age and handling, but the pages inside remarkably well preserved through careful storage and devotion.

My name is Grace, she began, her voice steady but emotional.

My great great grandmother was Ruth, the seamstress from Min who helped William and Ellen escape.

Our family has protected her story, her documents, her truth for five generations, waiting for the right moment to reveal everything.

She opened the Bible with practiced care to a middle section where several precious items had been pressed and preserved between the thin pages, a lock of dark hair tied with faded ribbon, a small pressed flower, a tarnished brass button, and most importantly, a letter written in careful, elegant script on paper that had yellowed but not deteriorated.

Ruth never spoke openly about what she did during her lifetime, Grace explained, her fingers gently touching the letter.

It was far too dangerous, even decades after the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished.

Former slave catchers still lived in Mon.

Confederate sympathizers held positions of power.

Speaking the truth, could have gotten her killed or at minimum driven out of business and into poverty.

The letter was dated December 1848 and addressed simply to those who come after me who seek truth.

Ruth’s words preserved across 170 years painted a vivid and detailed picture of an intricate conspiracy that made the escape not just possible but carefully planned and rehearsed.

She hadn’t worked alone in her dangerous mission.

Three other free black business owners in Mon had secretly coordinated the entire effort over months of preparation using their legitimate trade operations and business travel to smuggle materials, gather intelligence, move money, and create the elaborate disguise.

Ruth made six completely different suits over the course of two months, Grace explained, spreading out additional documents that showed fabric purchases and private notes.

Each one slightly different, perfecting the fit, the appearance, the tiny details that would make Ellen’s disguise absolutely convincing.

Ellen had to practice for weeks, walking like a wealthy man, sitting with masculine posture, even learning to sign documents with her left hand while keeping her right arm in a medical sling.

Marcus leaned forward intently, his decades of historical training focusing on this new information, the bandages and medical props.

Historians have debated for years about why Ellen’s face and hand were so elaborately wrapped.

We assumed it was simply to hide her features and avoid detailed scrutiny.

That was only part of Ruth’s brilliant strategy.

Grace confirmed with evident pride in her ancestors intelligence.

The bandages actually served four distinct tactical purposes simultaneously.

Grace reached into her leather bag again and carefully pulled out a second document, a small journal no bigger than a modern paperback book, its pages water stained and fragile with age, bound in faded cloth that had once been deep blue.

Ruth kept a coded record of every single person she helped between 1842 and 1855, she said reverently, handing it with extreme care to Sarah’s gloved hands.

97 people in total reached freedom through her network.

But William and Ellen were different from all the others.

Their escape was something more ambitious, more dangerous.

Sarah opened the journal slowly, finding entries written in a fascinating combination of standard English and what appeared to be substitution symbols and coded abbreviations.

The handwriting was neat and deliberate, suggesting entries written in quiet moments of safety rather than hurried notes.

“Is this a cipher system?” she asked, already recognizing patterns in the symbols.

“A relatively simple substitution code,” Grace confirmed, but effective for its purpose.

Ruth learned it from a traveling Methodist preacher named Samuel, who was secretly part of the Underground Railroads communication network spanning five states.

Each person she helped received two separate entries in the journal.

one when they first arrived seeking assistance and help and a second entry after they successfully reached freedom and sent word back confirming their safety.

Marcus began carefully photographing each page with the archives highresolution camera.

His hands steady despite his intense excitement at handling a primary source document that historians had never known existed.

Most entries were frustratingly brief.

Initials or single names, dates, vague destination references like north or Canada.

But the entries specifically about William and Ellen spanned six full pages filled with detailed observations, personal notes, concerns, and strategic planning.

December 3rd, 1848, Marcus read aloud, slowly translating the coded symbols into English.

E arrived after dark, brought by Samuel, determined in spirit, but terrified of discovery.

Facial features will pass under close scrutiny due to her heritage, but mannerisms and behavior need extensive work and practice.

W is protective, clearly intelligent, understands fully the enormous risks they face.

Both have memorized the detailed plan, but I remind myself that plans mean nothing when facing a slave catcher’s experienced eyes and suspicions.

The journal revealed crucial information that historians had never documented in any official records or published accounts.

The escape had been postponed and delayed twice due to dangerous circumstances.

Once because Ellen had fallen seriously ill with fever that lasted nearly a week, making travel impossible and dangerous.

And once because a notorious and particularly successful slave catcher named Hughes had been spotted operating in Charleston, directly along their carefully planned route.

Ruth’s intelligence network had sent urgent word, and they waited three additional anxious weeks until Hughes moved his operations to a different region.

“Here’s what puzzles me,” Sarah said, pointing to a cryptic entry from December 20th, just days before the actual escape.

Ruth writes, “Final preparation complete.

E knows what she must do in Baltimore.

Package prepared and concealed.

” What package? What was Ellen supposed to do in Baltimore beyond simply passing through on their journey north? Marcus spent the following week immersed in archives in Baltimore, following the tantalizing thread that Grace had revealed through Ruth’s coded journal.

What he discovered in the Maryland Historical Society’s restricted collection documents that required special permission and academic credentials to access left him absolutely stunned and fundamentally changed his understanding of the entire escape operation.

He called Sarah immediately from the archive reading room, his voice tense with barely contained excitement.

Sarah, I found the slave catcher’s official report.

It’s dated January 1849, just 3 weeks after William and Ellen successfully reached Philadelphia.

A man named Thomas Hughes, the same Hughes mentioned in Ruth’s journal, filed an extensive and detailed complaint with Baltimore Municipal authorities about what he called a sophisticated counterfeiting ring, producing false freedom papers of remarkable quality.

Hughes, Sarah confirmed, quickly checking her research notes in Ruth’s journal entries.

The same slave catcher whose presence in Charleston forced them to delay their escape by 3 weeks.

He was one of the most successful and feared slave catchers operating in the upper south.

Exactly right.

But here’s what’s absolutely fascinating and changes everything we thought we knew.

Marcus continued, his words tumbling out rapidly.

Hughes didn’t know specifically about William and Ellen at the time he filed this report.

He had no idea they had passed directly through Baltimore during their escape.

What he knew was that someone, some organized network, was creating extremely convincing forged documents, and he couldn’t identify the source or stop the operation.

Sarah felt her understanding shift as she pulled up the 1860 photograph on her computer screen again, studying Ellen’s face with new awareness.

So, they weren’t just escaping for themselves.

They were couriers carrying materials and tools to help establish or expand a document forging operation that would help many others escape.

Marcus’ excitement was audible even through the phone.

I found three additional documents.

Official freedom papers filed with Baltimore authorities between January and March 1849.

All for people who had connections to the Mon Georgia area.

The handwriting style, the paper quality, the official looking seals and signatures, they all matched the sophisticated style that Hughes described in his complaint.

Ruth’s network wasn’t just helping people escape.

They were creating the documentation infrastructure to make those escapes permanent and legal.

Three people, Sarah said softly, the human cost and courage becoming real.

Three more families freed because William and Ellen successfully carried the materials through Baltimore.

But the most shocking discovery came from an unexpected source that Marcus found later that day.

A private letter collection recently donated to the Maryland archives by a Baltimore family cleaning out their ancestral home.

Among mundane business correspondents was a letter from Hughes to a professional colleague dated February 1849 in which he described his intense frustration at being outwitted and made a fool by a sickly gentleman in fine clothes and his attentive negro servant who had passed through Baltimore carrying materials of subversion and rebellion that I only understood too late.

“He actually saw them,” Marcus said, his voice filled with awe.

Uh Hughes personally encountered William and Ellen during their escape, probably at a train station or hotel, but he didn’t recognize them because the disguise was so absolutely perfect.

The story of exactly why and how the 1860 photograph was systematically banned from American schools emerged from a dusty file box that Sarah discovered in the Georgia State Archives during a research trip to Atlanta.

She found it almost by accident, cross-referencing educational materials, curriculum debates, and textbook approval records from the 1880s and 1890s.

crucial decades after the Civil War ended, when reconstruction was violently collapsing across the South and Jim Crow laws were being strategically implemented to reestablish white supremacy through legal mechanisms.

A schoolboard meeting transcript from Atlanta dated October 1889 contained a heated and remarkably revealing debate about historical curriculum and what stories would be taught to the next generation of American children.

Board member Robert Thornton, a former Confederate officer and prominent Atlanta businessman, had objected strenuously and passionately to a new history textbook that included an engraving based on the craft photograph, accompanied by a several page account of their ingenious escape.

Sarah read his words aloud to Marcus during their nightly research call, her voice tight with anger at the deliberate eraser.

This image and accompanying narrative promote ideas that are dangerous to social order and harmony, that enslaved negroes possess the intelligence and capability to deceive their natural superiors, that the institution we once held as sacred and economically necessary was vulnerable to cunning and rebellious deception, and most dangerously of all, that a woman of mixed negro heritage could successfully and convincingly imitate a white gentleman of standing and refinement.

Such ideas undermine the natural social order.

He’s literally admitting in official records that teaching the truth threatens the ideological foundations of white supremacy.

Marcus said disgust and professional fascination mixing in his voice.

He’s saying the quiet part explicitly in a public meeting because in 1889 Atlanta he faced no social consequences for such statements.

The transcript revealed that Thornton succeeded in his campaign to have the textbook completely banned not just in Atlanta but eventually across Georgia and throughout most of the former Confederate states.

The photograph and the story were officially deemed inappropriate for young minds and historically inflammatory material that promotes social discord.

But northern states followed suit for different, though equally troubling reasons.

Schoolboard minutes that Sarah found from Boston in 1891 showed concerns that teaching the craft story in detail might encourage criminal deception among the lower classes and promote fundamental disrespect for property laws and contracts, revealing that even in the supposedly progressive North, the legal and economic rights of former enslavers were still being protected and prioritized decades after abolition.

What made the ban particularly insidious and effective was its remarkable geographic reach and longevity.

By 1895, Sarah’s research discovered the photograph and the detailed story had been systematically removed from school textbooks in 42 states through coordinated campaigns by school boards, textbook publishers, and educational authorities.

An entire generation of American children, millions of young people, grew up never learning about William and Ellen’s escape, never hearing about Ruth’s network, never understanding the sophisticated resistance movements that had operated successfully throughout the slaveolding south.

As Sarah and Marcus prepared their academic findings for publication and began coordinating with the Smithsonian’s exhibition team, Grace provided one final piece of evidence that fundamentally transformed their understanding of the entire underground railroad network operating throughout the Deep South during the 1840s and 1850s.

A map that historians had believed could not possibly exist.

It was drawn with remarkable precision on silk fabric carefully hidden inside the deteriorating lining of Ruth’s Bible where it had remained concealed and protected for over 170 years.

The map showed something that academic historians had long believed impossible to document.

A detailed network of safe houses, reliable contacts, and working routes stretching from Georgia through the Carolinas to Pennsylvania.

All coordinated and maintained by free black business owners who brilliantly used their legitimate trades and commercial activities as cover for their resistance work.

Uh, Ruth wasn’t working alone or in isolation, Grace explained carefully, spreading the delicate silk fabric across the archive table under controlled lighting.

She was part of an organized network of at least 27 people that we can identify from her records.

Tailor, blacksmiths, laresses, carpenters, shop owners, preachers, all legally free, all genuinely successful in their trades and businesses, all using their economic mobility and social respectability to help others escape bondage.

The silk map showed routes and pathways that directly contradicted everything in the published academic literature about underground railroad operations in the deep south.

Instead of following the traditional paths northward that white Quaker and Methodist abolitionists had documented in their memoirs and published accounts, this parallel network operated through commercial channels that white activists never knew existed.

Regular trade routes, scheduled market days, business conventions, and commercial shipping lines.

The white abolitionists who wrote the early histories of the Underground Railroad in the 1870s and 1880s, Marcus said slowly, understanding Dawning, they documented their own networks, their own heroic work and personal risks.

But they didn’t know about this parallel network because it deliberately stayed invisible to white people, even sympathetic and genuinely helpful white abolitionists.

Sarah nodded, carefully examining the intricate symbols and notations on the silk map with a magnifying glass.

Ruth’s network didn’t trust white abolitionists with complete information.

They had excellent reasons for that caution.

Some white helpers were actually paid informants working for slave catchers.

And even the most well-meaning white activists could be dangerously careless with sensitive information, not understanding the lethal consequences of exposure.

The silk map included sophisticated coded notes beside each marked location.

One symbol indicated safe for 3 days maximum.

Another meant avoid on Sundays when slave patrols increase.

Still, another symbol showed payment required, revealing the harsh reality that some freedom seekers had to somehow compensate their helpers with money or labor, adding yet another layer of difficulty and complexity to their desperate journeys.

But perhaps the most historically significant revelation came from the map’s date, carefully stitched into the silks corner, 1839.

Ruth’s network had been operating continuously for nine full years before William and Ellen’s famous 1848 escape, successfully helping dozens of people reach freedom while maintaining absolutely perfect operational security in the heart of the slaveolding south.

6 months later, on a warm spring morning, the Smithsonian opened its new permanent exhibition, Hidden Networks: The Untold Story of Southern Freedom Roots.

The 1860 craft photograph held the place of honor in the center gallery, dramatically displayed alongside Ruth’s coded journal, the remarkable silk map, the forged freedom papers from Baltimore, and interactive displays that allowed visitors to explore the network’s operations, tangible evidence of a sophisticated resistance movement that had operated successfully in plain sight for over 15 years.

Sarah stood quietly in the gallery on opening day, watching visitors of all ages pause before the photograph.

Many reading the detailed historical panels with expressions ranging from amazement to tears.

Many were descendants of freedom seekers, people who had traveled from across the country to finally see their ancestors stories properly acknowledged and honored in a national museum.

Grace stood beside Sarah, tears streaming freely down her face as she watched people carefully photographed Ruth’s journal entries and read about her great great-g grandandmother’s courage.

My grandmother spent her entire life protecting these documents, Grace whispered, her voice thick with emotion.

She died in 1998, never seeing them publicly recognized.

She always believed they mattered, that the truth mattered.

But she never lived to see this moment of vindication and honor.

The exhibition had already sparked an intense national conversation about whose stories get told and preserved in American history, whose voices are centered, and whose contributions are systematically erased.

School districts in 38 states were actively revising curricula to include the craft escape and Ruth’s network.

Universities were launching new research initiatives to identify other hidden networks and resistance movements that had operated during slavery and descendants were coming forward with family stories and documents long kept secret.

Marcus approached with a young woman who looked vaguely familiar, her features suggesting mixed heritage.

Sarah Grace, I want you to meet Dr.

Melissa Burton.

She’s a geneticist at Johns Hopkins and she has something remarkable to share about family connections.

Melissa smiled, nervous but excited.

I took a commercial DNA test last year, just casual curiosity about my ancestry.

The results connected me to someone else in the database, a descendant of William and Ellen, currently living in London.

We started comparing family histories, sharing documents and stories, and discovered something that changes the entire narrative.

She pulled out a tablet and showed them a meticulously researched family tree with documentation.

Ruth and Ellen were first cousins.

Their mothers were sisters, both enslaved on the same Georgia plantation before Ruth was freed in 1842.

Ellen didn’t go to a stranger for help.

She went to family.

She knew exactly who to trust because Ruth was blood.

Sarah felt goosebumps rise on her arms as the final piece fell into place.

The story kept revealing deeper layers of connection, courage, and carefully planned resistance.

That evening, as the museum prepared to close, Sarah returned alone to the gallery.

She stood before the 1860 photograph, studying Ellen’s face one more time.

The slight defiance in her direct gaze, the ornate brooch at her throat carrying its coded map of freedom, the expensive dress that declared her hard one humanity and dignity.

Ellen’s eyes seemed to look back through 160 years, as if she had known this moment would eventually come, as if she had deliberately left clues for someone who would care enough to look closely and tell the complete truth.

The photograph would never be forbidden

News

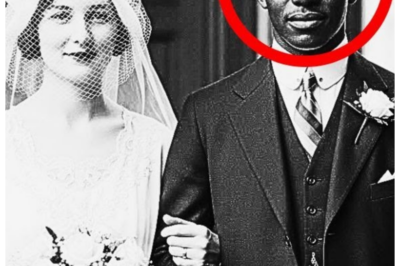

The Photo That History Tried to Erase: The Forbidden Wedding of 1920 Finally Resurfaces, and What It Shows Is Pure Scandal 💍 — Tucked away in a mislabeled archive box for nearly a century, this “lost” wedding portrait looks sweet at first glance—flowers, vows, forced smiles—but experts now say the couple should never have been allowed to marry, and the more the image is enhanced, the clearer it becomes that this wasn’t romance… it was rebellion captured in a single, dangerous frame 👇

The photo that history tried to erase. The forbidden wedding of 1920. The attic smelled of dust and forgotten memories….

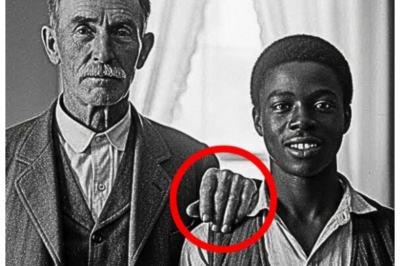

It Was Just a Photo Between Friends — Until Historians Uncovered a Dark Secret Hidden in the Shadows and the Smiles Suddenly Felt Fake 📸 — At first it looked like harmless laughter frozen in sepia, arms slung over shoulders, the kind of memory you’d tuck into a family album, but once experts enhanced the image they spotted a chilling detail tucked between them, and those cheerful expressions started to feel staged, like two people pretending everything was fine while hiding something they prayed no one would ever see 👇

It was just a photo between friends. But historians have uncovered a dark secret. Dr.James Patterson had spent his academic…

This 1898 Photograph Hides a Detail Historians Completely Missed — Until Now, and What They Found Has Them Questioning Everything 📸 — For decades it gathered dust in a quiet archive, labeled “ordinary,” dismissed as just another stiff Victorian snapshot, until a high-resolution scan exposed one tiny, impossible detail lurking in the background, and suddenly the smiles looked fake, the poses suspicious, and experts realized they weren’t staring at a memory… they were staring at a secret frozen in time 👇

This 1888 photograph hides a detail historians completely missed until now. The basement archives of the Charleston County Historical Society…

This Portrait of Two Friends Seemed Harmless — Until Historians Spotted a Forbidden Symbol Hidden Between Them and Everything Fell Apart ⚠️ — At first it was just two smiling companions shoulder-to-shoulder in stiff old-fashioned suits, the kind of wholesome image you’d frame without a second thought, but a closer scan revealed a tiny, outlawed mark tucked into the shadows, and suddenly the photo wasn’t friendship… it was rebellion, secrecy, and a message never meant to survive the century 👇

This portrait of two friends seemed harmless until historians noticed a forbidden symbol. The afternoon sun filtered through the tall…

Experts Thought This 1910 Studio Photo Was Peaceful — Until They Zoomed In and Saw What the Girl Was Holding, and the Entire Room Went Cold 📸 — At first it looked like another gentle Edwardian portrait, lace dress, soft lighting, polite smile, but when archivists enhanced the image they noticed her tiny fingers clutching something oddly deliberate, something that didn’t belong in a child’s hands, and suddenly the sweetness curdled into dread as historians realized this wasn’t innocence… it was a clue 👇

Experts thought this 1910 studio photo was peaceful until they saw what the girl was holding. Dr.Maya Johnson’s hands trembled…

This Portrait from 1895 Holds a Secret Historians Could Never Explain — Until Now It’s Finally Been Exposed in Stunning Detail 🖼️ — For more than a century it hung quietly in dusty archives, dismissed as another stiff Victorian pose, until a routine scan revealed a tiny, impossible detail that made experts freeze mid-sentence, because suddenly the calm expressions looked staged, the shadows suspicious, and the entire image felt less like art… and more like evidence 👇

The fluorescent lights of Carter and Sons estate auctions in Richmond, Virginia, cast harsh shadows across tables piled with forgotten…

End of content

No more pages to load