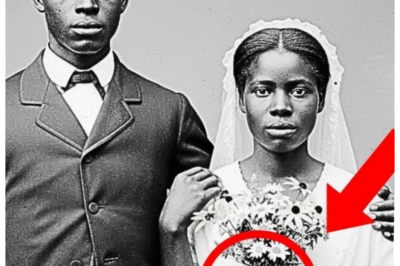

It was just a seemingly innocent wedding photo from 1920.

But pay attention to the groom’s hand.

The Maxwell estate sale in downtown Chicago was winding down on a gray October afternoon in 2024.

Most of the valuable items had already been claimed.

Antique furniture, jewelry, paintings, leaving behind the forgotten remnants of a life that few people cared to remember.

David Chen, an archivist for the Chicago History Museum, had arrived late, squeezing in a visit between meetings.

He wasn’t expecting to find anything significant, but estate sales sometimes yielded surprising historical treasures, and his job required diligence, even when prospects seemed dim.

He wandered through rooms filled with dusty boxes and half empty shelves, his trained eyes scanning for anything that might have historical value.

Most of what remained was ordinary, outdated electronics, worn clothing, paperback novels with cracked spines.

But in a corner of the attic, beneath a stack of yellowed newspapers from the 1950s, David found a leatherbound photo album.

The cover was cracked and faded, the binding loose.

But when he opened it carefully, he found dozens of photographs from the 1920s and 1930s.

Their sepia tone surprisingly well preserved despite decades of neglect.

David paid $15 for the album and carried it back to his office at the museum.

The building was quiet that evening, most of his colleagues having left for the day.

He sat at his desk under the bright LED lamp and began examining each photograph methodically, documenting what he saw.

There were family gatherings, children playing in yards, men in fedoras standing beside Model T Fords, women in flapper dresses posing on porches.

Each image was a small window into the past, into lives lived and forgotten.

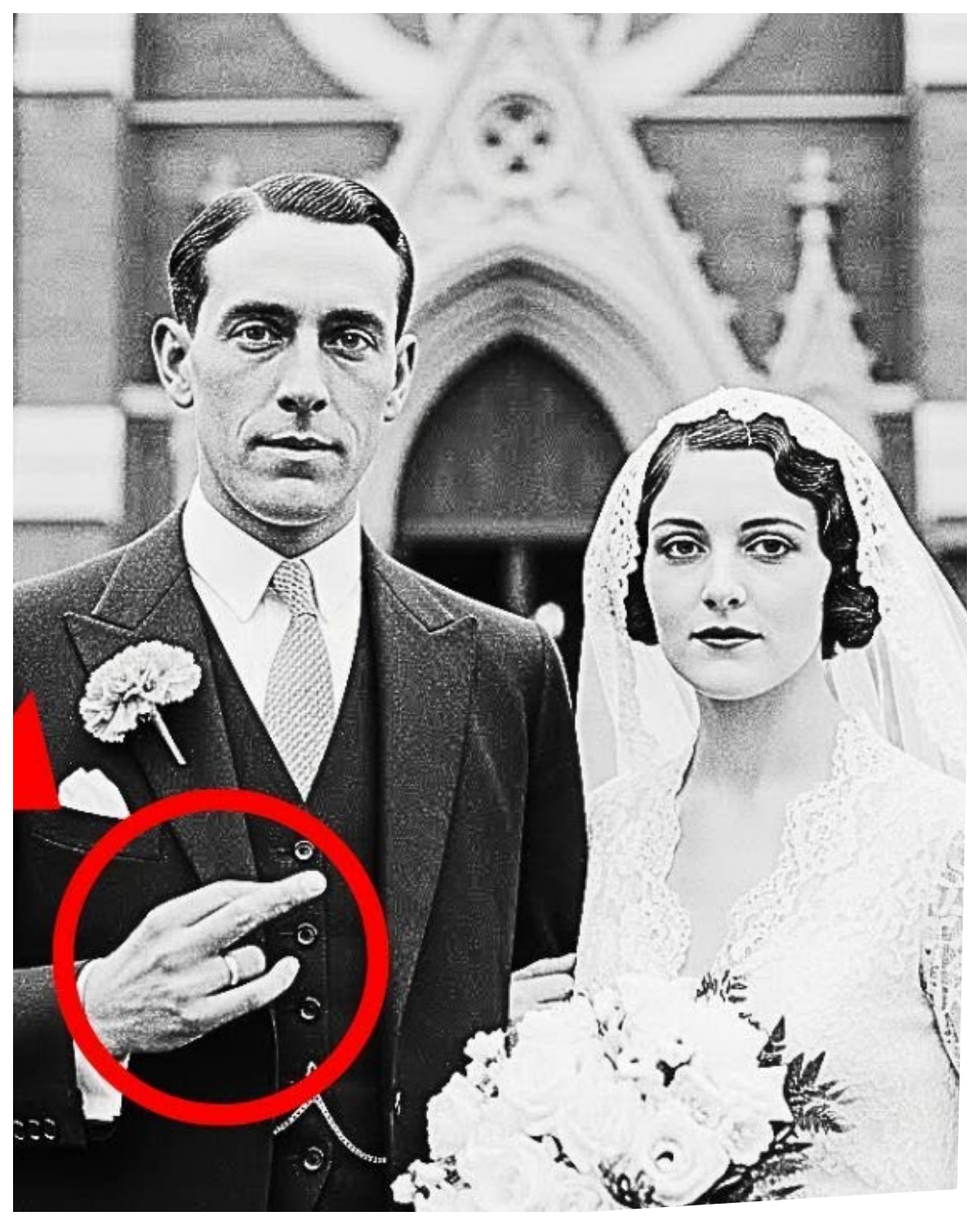

Then he turned to a page near the middle of the album and found the wedding photograph.

It was larger than the others, clearly the centerpiece of this particular section.

A young couple stood on the steps of a church, surrounded by what appeared to be family members and guests.

The bride wore an elegant white dress with delicate lace detailing, a long veil cascading down her back, and she held a bouquet of flowers.

Her expression was serene, almost blank, the kind of formal pose common in photographs from that era.

The groom stood beside her in a dark suit with a white shirt and tie, his hair neatly combed, his face serious.

Behind them, the church’s stone facade rose impressively, and to the sides, guests in formal attire watched the couple.

At the bottom of the photograph, written in faded ink, was a caption, “Vincent and Catherine, June 12th, 1926, St.

Michael’s Church, Chicago.

” David studied the image for a moment, noting the formality and composition typical of wedding photographs from the Prohibition era.

Everything seemed ordinary, unremarkable, just another young couple beginning their lives together in the turbulent 1920s.

But something about the groom’s posture caught his attention.

Vincent stood slightly stiffly, his shoulders tense, his jaw set in a way that suggested discomfort rather than joy.

His left arm was linked with Catherine’s, as was customary, but his right arm hung at his side in a position that seemed oddly deliberate.

David leaned closer, squinting at the photograph under the lamp.

The groom’s right hand was positioned strangely.

His fingers weren’t relaxed or naturally curved, but instead formed a specific configuration that seemed intentional.

David felt a prickle of curiosity.

He pulled out his phone and took a highresolution photograph of the wedding picture, then uploaded it to his computer and zoomed in on the groom’s hand.

His breath caught in his throat.

The fingers weren’t randomly positioned.

They were forming letters, sign language letters.

And as David traced the configuration, his stomach tightened.

The hand was spelling something.

H E L P.

David sat frozen at his desk, staring at the zoomed-in image on his computer screen.

The groom’s hand was unmistakable now that he could see it clearly.

The thumb, index, and middle fingers formed the letter H in American Sign Language, or at least the beginning of a sequence that spelled out a desperate message.

He’d spent enough time cataloging historical photographs and studying visual communication methods to recognize sign language when he saw it, even partially obscured by the limitations of 1920s photography.

He zoomed out slightly and examined the entire photograph again, looking for other clues he might have missed.

The bride, Catherine, stared straight ahead with an expression that was difficult to read, serene perhaps, or simply blank in the way people often appeared in formal photographs before smiling became standard.

The guests surrounding the couple looked equally formal, their faces showing little emotion.

But Vincent, the groom, had a tension in his jaw and eyes that seemed out of place for a man on his wedding day.

David picked up his phone and called Dr.

Rebecca Hail, a colleague who specialized in accessibility history in sign language communication in early 20th century America.

Rebecca was one of the few historians in Chicago who had extensively studied how deaf and hearing communities communicated before modern standardization of ASL.

And she had helped the museum authenticate several historical documents involving sign language.

Rebecca, it’s David Chen from the museum.

I’m sorry to call so late, but I need your expertise on something unusual.

No problem, David.

What do you have? A wedding photograph from 1926.

The groom’s hand is positioned in what looks like sign language.

Can you come take a look? 20 minutes later, Rebecca arrived at the museum, her coat still damp from the light rain that had begun falling outside.

She was a woman in her late 40s with sharp, observant eyes and graying hair pulled back in a practical ponytail.

David showed her the photograph, both the original in the album, and the highresolution image on his computer screen.

Rebecca studied the image in silence for several minutes, zooming in and out, examining the hand from different angles.

Finally, she sat back and removed her glasses, cleaning them absently as she processed what she had seen.

That’s definitely intentional, she said quietly.

The hand position is too precise to be accidental.

He’s forming ASL letters, H E L P, four letters spelled out as clearly as possible while trying to appear casual.

So, he was asking for help at his own wedding.

Rebecca nodded slowly.

It appears so.

But here’s what’s interesting.

ASL wasn’t as widely known in the 1920s as it is today, especially among hearing people.

For someone to use it as a distress signal, they would need to either be part of the deaf community or have close contact with someone who was.

And they would need to assume that someone viewing the photograph would understand the message.

David felt his pulse quicken.

So, this wasn’t just a random gesture.

He deliberately chose a method of communication that would be invisible to most people, but readable to someone who understood.

Exactly.

and look at his face, the tension, the stiffness.

This man was under duress.

They sat in silence for a moment, the weight of the discovery settling over them.

A wedding photograph from 1926, seemingly ordinary, now revealed itself as something much darker.

A silent cry for help preserved for nearly a century.

The following morning, David arrived at the museum early and immediately began researching Vincent and Catherine’s wedding.

The photograph had provided two crucial pieces of information: names and a date.

June 12th, 1926 at St.

Michael’s Church in Chicago.

It wasn’t much, but it was enough to start.

Chicago in the 1920s was a city defined by prohibition, organized crime, political corruption, and rapid social change.

It was also a city that kept records, church registries, marriage licenses, newspaper announcements, property deeds, all of which might contain clues about who Vincent and Catherine were and what had happened to them.

David started with the Chicago Public Libraryies digital archives, searching for marriage announcements from June 1926.

He scrolled through digitized newspaper pages, scanning the society sections where weddings were typically announced.

Most were brief notices with names, dates, and locations, but some included more detail, descriptions of the bride’s dress, lists of prominent guests, mentions of receptions, and honeymoon plans.

He found the announcement on page seven of the Chicago Tribune, dated June 13th, 1926.

Miss Katherine Marie Rossi, daughter of Mr.

and Mrs.

Antonio Rossi of the near west side, was united in marriage to Mr.

Vincent James Marcelo of Little Italy yesterday afternoon at St.

Michael’s Church.

The ceremony was attended by family and close friends.

The couple will reside in Chicago.

David wrote down the names carefully.

Rossi and Marello, both Italian surnames, common in Chicago’s immigrant communities during that period.

The near west side and little Italy were neighborhoods with large Italian populations, areas that had been significantly impacted by prohibition and the rise of organized crime.

Alapone’s empire had been built partly on the backs of Italian immigrant communities, some members of which had been pulled into bootlegging, gambling, and other illegal enterprises.

He searched for Antonio Rossi next, looking for any mentions in newspapers, business directories, or court records.

The name was common enough that dozens of results appeared, but David filtered them by location and time period.

He found several Antonio Rossies listed in Chicago directories from the 1920s.

A grosser, a construction worker, a saloon owner.

The saloon owner caught his attention.

In 1926, legitimate saloons had been closed for 6 years due to prohibition, which meant that anyone still listed as a saloon owner was likely operating a speak easy or involved in illegal alcohol distribution.

David cross referenced the address listed for Antonio Rossi, saloon owner, with historical maps of Chicago.

The location was in the near west side, exactly where the wedding announcement had indicated Catherine’s family lived.

He felt a surge of excitement.

This might be the right Antonio Rossi.

Next, he searched for Vincent James Marcelo.

This search proved more difficult.

The name appeared in several contexts, but none that immediately connected to the wedding or to the Rossy family.

David tried different approaches, searching for obituaries, court records, immigration documents.

Finally, in a 1925 city directory, he found a listing.

Marello, Vincent J.

accountant, residing 412 South Holstead Street.

An accountant.

David sat back, considering the implications.

Accountants handled money, kept books, tracked financial transactions.

During Prohibition, when illegal businesses generated enormous cash flows that needed to be hidden from authorities, accountants were valuable and vulnerable.

David needed help navigating the complex world of Chicago’s prohibition era organized crime.

He reached out to Dr.

Thomas Brennan, a historian at Northwestern University who had written extensively about the intersection of Italian immigration, organized crime, and urban development in 1920s Chicago.

Thomas had spent decades researching the social structures that had enabled figures like Al Capone to rise to power, and he had access to archives and sources that most historians never saw.

They met for coffee at a cafe near the university campus.

Thomas was a man in his early 60s with a thick gray beard and wire rimmed glasses.

His appearance more professorial than the subject matter he studied might suggest.

David brought printouts of everything he had found.

The wedding photograph, the newspaper announcement, the directory listings for Antonio Rossi and Vincent Marello.

Thomas studied the materials carefully, occasionally making notes in a small leatherbound notebook he carried everywhere.

When he reached the photograph, and David pointed out the sign language message in Vincent’s hand, Thomas’s expression shifted from casual interest to intense focus.

This is remarkable, Thomas said quietly.

A documented distress signal from someone caught in what was likely a forced marriage.

Do you know how rare this is? Most people in Vincent’s position disappeared without leaving any trace, any evidence.

But he found a way to communicate, to leave a record.

What can you tell me about the Rossi family? David asked.

Thomas pulled out his laptop and began searching through his research database, a massive collection of documents, photographs, and records he’d compiled over decades.

Antonio Rossi.

Yes, I have information on him.

He ran a speak easy on the near west side, one of several dozen in that neighborhood.

But he wasn’t just a small-time operator.

He was connected to the Jenna brothers.

David recognized the name.

The Jenna brothers had been major figures in Chicago organized crime during the early 1920s, controlling much of the illegal alcohol production and distribution in Italian neighborhoods.

They had been rivals and sometime allies of Al Capone, operating a network of home distilleries that produced industrial alcohol for conversion into bootleg liquor.

The Jennas were ruthless, Thomas continued.

They didn’t tolerate disloyalty or testimony against them.

Anyone who threatened their operations was eliminated, often publicly to send a message.

By 1926, most of the Jenner brothers themselves were dead, killed in gang wars or by Capone’s forces, but their network continued operating under various successor organizations.

And Antonio Rossi was part of that network.

Thomas nodded.

According to police surveillance reports I’ve seen, yes, he supplied liquor to multiple speak easys and was suspected of involvement in several violent incidents.

Though he was never successfully prosecuted, he had connections protection.

In 1926, that kind of protection usually came from someone higher up in the organization, either Capone’s outfit or one of the smaller gangs that operated semi-independently.

David felt the pieces beginning to connect.

So if Vincent Marcelo was an accountant and if he somehow got involved with the Rossy family’s operations, then he would have seen things.

Thomas finished records, money flows, names of people involved.

He would have become a liability the moment he knew too much.

Understanding Vincent Marello required tracing his life before the wedding before he became entangled with the Rossy family.

David spent days searching through immigration records, census data, city directories, and church registries, slowly building a picture of a young man trying to make his way in a city that offered both opportunity and danger.

Vincent James Marello had been born in Chicago in 1902.

The son of Italian immigrants from Sicily who had arrived in America in 1898.

His father, Joseph Marello, worked as a tailor, operating a small shop in Little Italy.

His mother, Rosa, took in laundry and did peacework sewing to supplement the family’s income.

Vincent had two younger sisters, Maria and Teresa, both of whom attended local Catholic schools.

According to school records, David found at the Chicago Board of Education archives.

Vincent had been an excellent student, graduating from a public high school in 1920 with high marks in mathematics and languages.

He had attended a commercial college for two years, studying bookkeeping and accounting, practical skills that offered a path to middle class stability.

By 1923, at age 21, he was working as an accountant for a wholesale grocery company on the south side.

The 1925 city directory listed him at a boarding house on South Holstead Street, suggesting he had moved out of his parents’ home, probably seeking independence and proximity to work.

Everything in Vincent’s background pointed to a young man following a conventional path.

Education, steady employment, gradual social mobility.

There was nothing in the records that suggested criminal connections or involvement with organized crime.

But then in early 1926, something changed.

David found a brief mention in a March 1926 business journal, noting that Vincent Marello had left his position at the wholesale grocery company to pursue other opportunities.

No details were provided, and Vincent’s name didn’t appear in any other employment listings until after the wedding.

David showed these findings to Thomas Brennan, who studied them thoughtfully.

“Young accountants in the 1920s were valuable to criminal organizations,” Thomas explained.

“They understood financial systems, could keep accurate books, and could help hide money from authorities.

Sometimes they were recruited willingly, lured by the promise of higher pay than legitimate work offered.

But sometimes they were forced, blackmailed, threatened, or simply trapped by circumstances they didn’t fully understand until it was too late.

So Vincent might have been approached by the Rossi family or their associates.

It’s possible if Antonio Rossy’s operation was growing in early 1926, he would have needed someone to manage the financial side, tracking inventory, recording transactions, laundering money.

An educated young man like Vincent with accounting skills but no criminal connections would have been an ideal target.

He could be controlled more easily than someone already embedded in the criminal world.

David considered this.

And once Vincent was working for them, once he saw their records and operations, he became too dangerous to let go, Thomas said grimly.

He knew too much.

They couldn’t just let him walk away and potentially testify against them or sell information to rival gangs.

They needed to ensure his loyalty by forcing him to marry into the family.

Thomas nodded.

Marriage created legal and social bonds that were harder to break.

It meant Vincent was now family, which in Italian-American organized crime culture carried specific obligations and expectations.

And it gave the Rossies leverage if Vincent betrayed them, his wife, his potential children.

Even his own parents and sisters could be threatened.

David and Rebecca worked together to analyze the wedding photograph in greater detail, looking for any other clues beyond Vincent’s distress signal.

They examined every visible face, every detail of clothing and positioning, every element of the composition.

The photograph had been taken by a professional.

The lighting was well balanced, the focus sharp, the arrangement formal and traditional.

Whoever had commissioned it had paid for quality.

Rebecca pointed to the guests surrounding the couple.

Look at their expressions.

Most wedding photographs from this era show at least some warmth, some joy from family members, but these people, they look stern, almost watchful.

See this man here? She indicated a heavy set man in a dark suit standing slightly behind and to the right of Catherine.

His arms are crossed and he’s staring directly at the camera with an expression that’s almost challenging.

That’s not typical for a wedding guest.

David zoomed in on the man’s face.

He was probably in his 50s with a broad face and thick eyebrows.

His suit was expensive, well tailored, suggesting wealth or at least access to it.

Could that be Antonio Rossi? Rebecca compared the face to a grainy newspaper photograph David had found of Antonio Rossi from a 1924 article about a speak easy raid.

It could be the features are similar, the broad face, the heavy build.

If that’s him, then his positioning is significant.

He’s standing guard essentially watching.

They examined other faces in the photograph.

Catherine’s mother presumably stood on the bride’s other side, a thin woman in a dark dress, her face pinched and anxious.

Several young men in suits stood in the background, their postures suggesting they were there more as security than a celebrance.

There were no visible smiles, no expressions of joy or celebration.

This doesn’t look like a happy occasion, David said quietly.

It looks like a business transaction.

Rebecca nodded.

And Vincent knew it.

That’s why he left the message.

He was hoping someone someday would see it and understand.

David decided to search for more information about the actual wedding day.

He went through Chicago newspaper archives looking for any mentions of the event beyond the standard marriage announcement.

Most weddings weren’t covered in detail unless the families were particularly prominent, but sometimes society columnists mentioned notable events or gatherings.

He found something unexpected in a police blott from June 13th, 1926, the day after the wedding.

A brief entry noted disturbance reported at 847 West Taylor Street near Westside.

Officers responded, “No arrests made.

complainant declined to press charges.

David cross- referenced the address with historical records in 1926.

That address had been a residential building containing several apartments.

One of them had been rented to Vincent Marcelo, according to city directory listings.

The disturbance had been reported the day after his wedding.

What had happened? Had Vincent tried to escape? Had there been a confrontation? The police report was frustratingly vague, providing no details about the nature of the disturbance or who had been involved.

But the fact that no arrests were made despite officers responding suggested either that the situation had been resolved quickly or that someone had enough influence to make the police leave without taking action.

Tracing what happened to Vincent and Catherine after the wedding proved challenging.

Unlike prominent families whose lives were documented in society pages and business journals, workingclass and lower middle-class people left fewer traces in the historical record.

But David was persistent, searching through census records, city directories, property records, and newspaper archives, looking for any mention of either Vincent or Katherine Marello in the years following 1926.

The 1930 census provided the first significant clue.

David found Katherine Marello, aged 26, listed as widowed and living with her parents, Antonio and Maria Rossi, at an address on the near west side.

No children were listed.

The occupation column for Catherine was blank.

Vincent was not listed anywhere in the 1930 census for Chicago or surrounding areas.

David expanded his search to other cities, other states, but found nothing.

It was as though Vincent had simply vanished sometime between 1926 and 1930.

David contacted the Chicago Police Department’s records division, requesting any reports or documents related to Vincent Marello from the period.

It took two weeks to receive a response, and when it came, it was disappointingly brief.

No missing person reports had been filed for Vincent Marello and no criminal investigations involving him as either suspect or victim appeared in the archives.

That’s not surprising, Thomas Brennan said when David shared this information.

In the 1920s, the Chicago police were notoriously corrupt, especially when it came to organized crime.

If Vincent was killed by the Rossy family or their associates, the police either wouldn’t have investigated or would have been paid to look the other way.

And if his own wife reported him missing, she would have been pressured by her family to drop the matter.

David found one more crucial document, a death certificate filed in February 1927, 8 months after the wedding.

Vincent James Marcelo, aged 24, cause of death listed as accidental drowning.

The body had been found in the Chicago River near the South Branch, identified by personal effects.

The death certificate was signed by a coroner David later discovered had been investigated multiple times for falsifying reports and suspicious deaths connected to organized crime, though he was never successfully prosecuted.

Accidental drowning, Rebecca said skeptically when David showed her the document.

One of the most common cover stories for murder in 1920s Chicago.

Bodies dumped in the river were often listed as drownings, especially if the victim had been waited down or if decomposition made determining the actual cause of death difficult.

David felt a deep sadness settling over him as he stared at the death certificate.

Vincent had been 24 years old, just beginning his adult life, when he had been forced into a marriage he clearly didn’t want.

He had tried to signal for help in the only way he could, using a form of communication he hoped someone would eventually understand.

And 8 months later, he was dead.

“He must have tried to leave,” David said quietly.

“Or maybe he threatened to go to the authorities.

Either way, they killed him.

” Thomas nodded grimly.

That was the typical pattern.

Force someone into compliance through marriage or threats.

Use them for as long as they are useful and eliminate them when they become too much of a risk.

Vincent probably knew too much about the Rossy family’s operations.

They couldn’t let him live.

Not once he’d made it clear he wasn’t going to cooperate willingly.

Understanding what happened to Catherine after Vincent’s death required delving into records that were harder to find and interpret.

Unlike Vincent, whose life had been cut short, Catherine had continued living, at least through the 1930 census.

But what kind of life had it been? Had she been complicit in whatever had happened to Vincent? Or had she been another victim of her family’s criminal activities? David found Catherine listed in the 1940 census as well, still living with her parents, now aged 36, occupation still listed as blank, marital status still widowed.

Well, no subsequent marriages appeared in Chicago marriage records.

She seemed to have simply remained in her parents’ household, unmarked by further major life events that would have left documentary traces.

Then in a 1952 newspaper obituary, David found a death notice.

Katherine Marcelo, 48, died peacefully at home on March 7th.

She was preceded in death by her husband, Vincent, and her parents, Antonio and Maria Rossy.

Private services were held at St.

Michael’s Church.

No surviving family.

All died peacefully at home.

No surviving family.

The brief notice raised more questions than it answered.

What had Katherine’s life been like in the 26 years between Vincent’s death and her own? Had she known what her family had done? Had she been forced into the marriage against her will? Or had she been a willing participant in her father’s schemes? David decided to search for any personal documents, letters, diaries, or other materials that might have survived.

He contacted the arch dascese of Chicago, asking if St.

Michael’s church still existed and if they maintained historical records from the 1920s and 1950s.

The response came a week later.

St.

Michaels had closed in 1985 and been demolished, but some records had been transferred to the arch diosis and archives.

David visited the archives, a climate controlled facility in a modern building on the north side.

An archivist helped him locate the boxes containing St.

Michael’s historical records.

Most were baptismal certificates, marriage records, and burial information, but there was also a small collection of personal papers that had been donated by parishioners over the years.

In one box, David found a sealed envelope marked Katherine Marcelo, personal effects, 1952.

Inside were several items, a rosary, a small prayer book, and three letters.

The letters were addressed to Vincent, but had never been sent.

They had no postage stamps or mailing addresses.

David carefully unfolded the first letter, dated December 1926, 4 months after the wedding.

My dearest Vincent, it began.

I know you cannot read this, but I write it anyway because I must tell someone the truth, even if that someone is only the memory of you.

I am so sorry.

I did not know what my father had planned.

I thought you came to our home willingly, that you wanted to marry me.

I was foolish and vain, and I believed what I wanted to believe.

By the time I understood what was really happening, it was too late.

David’s hands trembled as he continued reading.

Catherine’s letters painted a devastating picture of two young people trapped by circumstances neither fully controlled.

The second letter, dated January 1927, was longer and more detailed.

Catherine described how her father had brought Vincent into their home in early 1926, introducing him as an accountant who would help manage the family’s business interests.

She had been 22 at the time, unmarried, and her father had been increasingly pressuring her to find a suitable husband.

“Vincent was kind to me,” Catherine wrote.

He spoke gently, treated me with respect.

I thought perhaps he cared for me.

But I see now that he was simply a good man trying to survive an impossible situation.

My father told him that if he did not agree to marry me, his own family would suffer.

His parents, his sisters.

My father threatened them all.

What choice did Vincent have? The letter went on to describe the wedding day from Catherine’s perspective.

She had noticed Vincent’s tension, his reluctance, but had misinterpreted it as nervousness.

Only later, after they were alone in the apartment her father had rented for them, did Vincent finally speak honestly to her.

He told me he did not want to marry me.

Catherine wrote, “He told me he had been forced, that my father held his family safety over him like a knife.

He was not cruel about it.

He apologized for being honest.

Said he knew it was not my fault.

But he also told me he could not pretend, could not live a lie.

He said he would find a way to escape, to go to the authorities, to expose my father’s operations.

” David read the words with growing understanding.

Vincent had tried to resist, had planned to go to the police or federal authorities with evidence of the Rossy family’s criminal activities.

But in 1926, Chicago going to the authorities was dangerous.

The police were often corrupt, prosecutors could be bribed, and federal agents were few and overwhelmed by the scale of prohibition era crime.

The third letter, dated February 1927, the same month as Vincent’s death, was the most heartbreaking.

Katherine’s handwriting was less controlled.

The ink smudged in places as though tears had fallen on the paper.

“They killed him,” she wrote simply.

“My father and my uncles, they killed Vincent because he refused to cooperate, because he was going to expose them.

They made it look like an accident, like drowning.

But I know the truth.

I heard them talking late at night.

Heard my father say that Vincent had become a problem that needed solving.

” And I should have warned him.

I should have helped him escape.

But I was afraid and I did nothing.

And now he is dead because of my cowardice.

The letter continued describing Catherine’s guilt and isolation.

She wrote that she had considered going to the police herself, telling them what she knew about Vincent’s death and her father’s operations, but she was terrified of what her father would do if she betrayed him.

“He would kill me, too,” she wrote.

Or worse, he would kill Vincent’s family.

“I cannot bear the thought of more innocent blood on my hands.

” Catherine’s solution had been to withdraw from life entirely.

She stopped socializing, stopped leaving the house except for church.

She lived with her parents, but barely spoke to them.

She never remarried, never had children, never built a life of her own.

“This is my penance,” she wrote.

“To live with the knowledge of what was done, what I failed to prevent.

” “David knew that the story of Vincent and Catherine needed to be told, not just as a historical curiosity, but as a testament to lives destroyed by violence and coercion.

He organized a public presentation at the Chicago History Museum, inviting historians, journalists, descendants of Chicago’s Italian-American community, and anyone interested in the hidden stories of Prohibition era crime.

The presentation room was packed.

David stood at a podium with the wedding photograph projected on a large screen behind him, Vincent’s hand and its silent cry for help visible to everyone.

He walked the audience through his investigation, the discovery of the photograph, the identification of the sign language message, the research into the Rossy family’s criminal connections, the tragic arc of Vincent’s life, and Catherine’s letters revealing her guilt and grief.

This photograph captures a moment of profound injustice, David said.

A young man forced into marriage through threats against his family, desperately signaling for help in a way he hoped someone would eventually understand.

Vincent Marello died eight months after this photo was taken.

Murdered because he refused to be complicit in organized crime.

And Katherine Rossy lived for another 26 years carrying the burden of what happened, punishing herself with a lifetime of isolation and silence.

The room was silent as David finished speaking.

Then a woman in the front row raised her hand.

She was elderly, perhaps in her 70s with silver hair and sharp, intelligent eyes.

My name is Maria Santoro, she said.

Vincent Marello was my mother’s brother, my uncle, though he died decades before I was born.

My family never talked about him.

They said he died in an accident that we shouldn’t ask questions.

I grew up knowing his name, but nothing about his life.

Thank you for giving him back to us.

Over the following weeks, David was contacted by several other descendants of people connected to the story.

Vincent’s sister Teresa had died in 1989, but her children and grandchildren were still living in Chicago.

They had photographs, letters, and family stories that helped fill in details of Vincent’s early life.

They confirmed that the family had been threatened in 1926, that they had been told to stop asking questions about Vincent’s death or face consequences.

David also heard from descendants of other men who had been forced into marriages with daughters of organized crime families during the prohibition era.

The practice had been more common than historical records suggested, a form of coercion that left few traces because victims rarely survived long enough to testify, and families were too frightened to report what had happened.

The wedding photograph was placed on permanent display at the Chicago History Museum as part of an exhibit on Prohibition era crime and its impact on immigrant communities.

Alongside it were Catherine’s letters, Vincent’s death certificate, and historical context explaining how organized crime had exploited and destroyed lives.

The exhibit included information about sign language as a form of resistance and communication, connecting Vincent’s desperate signal to broader histories of how marginalized people had found ways to speak when direct speech was dangerous.

Maria Santoro attended the exhibit opening with several family members.

They stood together looking at the photograph of their uncle, finally understanding what had happened to him and why his death had been shrouded in silence for so long.

He was trying to tell us, Maria said quietly.

All these years he was trying to tell us.

And now, finally, we can hear him.

David stood nearby, watching families connect with their histories, watching people understand that hidden stories could be recovered, that voices silenced by violence could still speak across time.

Vincent’s hand in that photograph had spelled out a simple word, help.

And nearly a century later, someone had finally answered.

News

This 1889 studio portrait looks elegant — until you notice what’s on the woman’s wrist

This 1889 studio portrait appears elegant until you notice what’s wrapped around the woman’s wrist. Dr.Sarah Bennett had spent 17…

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters—but then historians noticed their hands

At first, it looked like a photo of two sisters, but then historians noticed their hands. The archive room of…

It was just a portrait of a soldier and his wife—until you notice what he’s holding

It was just a portrait of a soldier and his wife until you notice what he’s holding. The photograph arrived…

It was just a portrait of a mother — but her brooch hides a dark secret

It was just a portrait of a mother and her family, but look more closely at her brooch. The estate…

This 1925 wedding photo has been restored — and what appeared in the mirror shocked historians

This 1925 wedding photo has been restored, and what appeared in the mirror shocked historians. The photograph arrived at the…

It was just a portrait of newlyweds — until you see what’s in the bride’s hand

It was just a portrait of newlyweds until you see what’s in the bride’s hand. The afternoon light filtered through…

End of content

No more pages to load