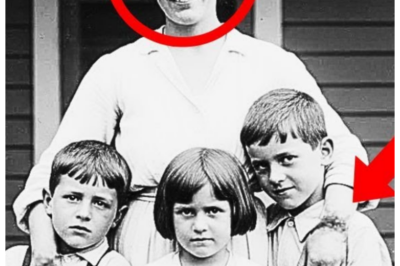

It was just another wedding photo from 1883 until you found out the bride’s age.

The Charleston Historical Society’s archive room smelled of old leather and preservation chemicals, a scent that Rebecca Chen had grown to love over her 5 years as head archivist.

The March afternoon sun filtered through tall windows, casting geometric patterns across the rows of filing cabinets and storage boxes that held centuries of South Carolina history.

Rebecca was processing a recent estate donation from the former plantation district.

boxes of photographs, letters, and legal documents from families that had once formed Charleston’s upper class.

Most of the material was standard business correspondents, property deeds, family portraits.

But it was the photographs that always captivated her, these frozen moments that offered glimpses into lives long finished.

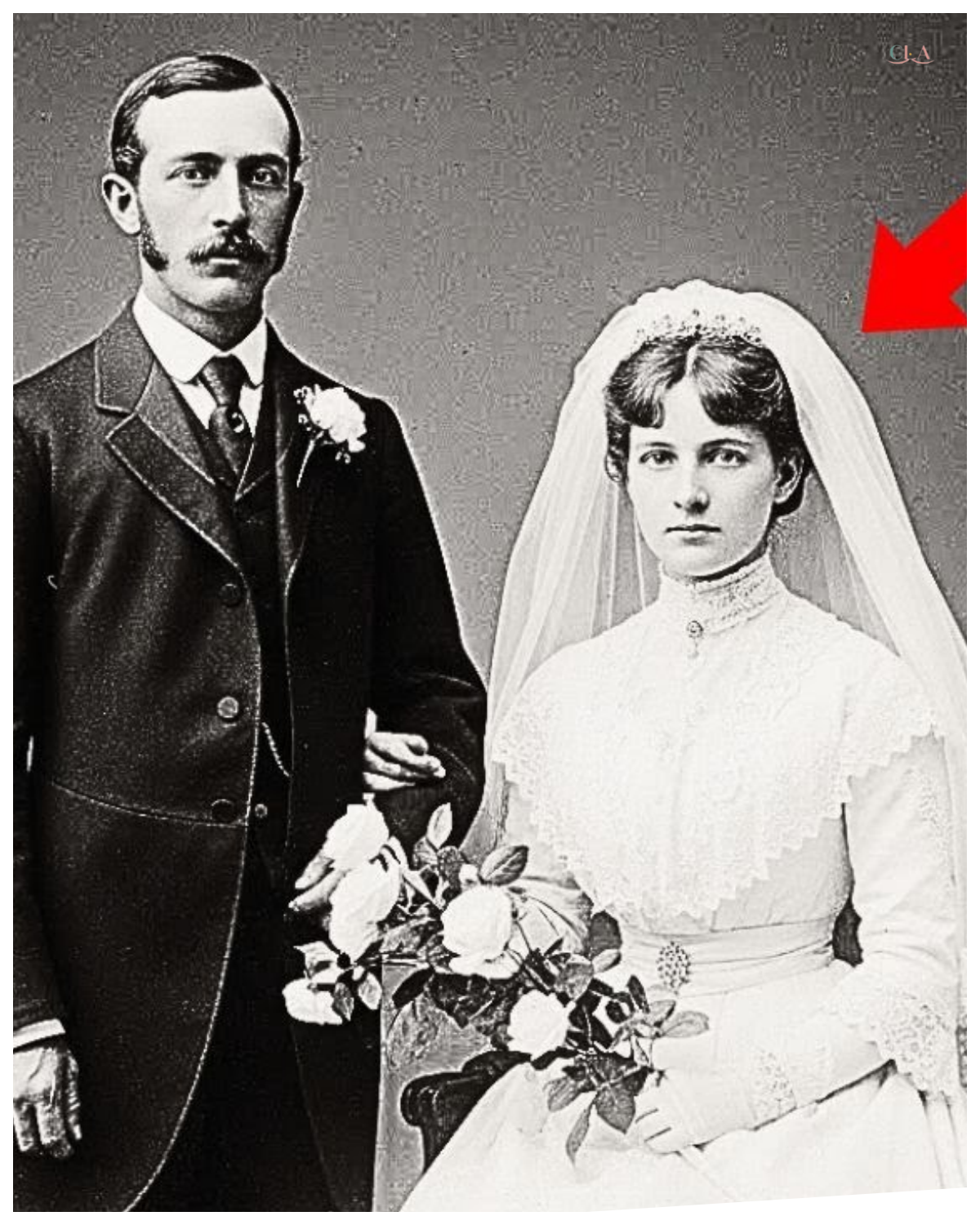

She carefully unwrapped a large wedding photograph from its protective tissue paper.

The image showed a couple posed formally in what appeared to be a well-appointed parlor.

The groom stood tall and confident, his dark suit immaculate, a thick beard neatly trimmed, his hand resting possessively on an ornate chair.

Beside him sat the bride, her white lace dress elaborate and expensive, her veil pulled back to reveal her face.

Rebecca positioned the photograph under her desk lamp and felt her breath catch.

The bride looked extraordinarily young, not just young for a bride, but genuinely childlike.

Her face still held the soft roundness of early adolescence, her hands small and delicate, where they clutched a bouquet of white roses.

She sat stiffly, her expression not joyful, but frozen, almost fearful.

The groom, by contrast, appeared to be in his mid to late 30s, his face showing the weathering of maturity and experience.

The age difference was stark, unsettling in a way that made Rebecca’s professional detachment falter.

She turned the photograph over.

On the back, written in elegant script was an inscription.

William and Sarah, wedding day, June 14th, 1883, Charleston, South Carolina.

Below that, in smaller writing, may God bless this union.

Rebecca set the photograph down and reached for the accompanying documents in the donation box.

There had to be more information.

Marriage certificates, family records, something that would provide context.

Her fingers found a folded piece of paper yellowed and fragile.

She opened it carefully.

It was the marriage certificate.

Her eyes scanned the document until they reached the line listing the bride’s age, 13 years old.

Rebecca stared at the marriage certificate, her modern sensibilities clashing with the historical reality before her.

13 years old.

The words seemed impossible, though she knew intellectually that child marriage had been legal in many states throughout the 19th century.

Knowing it historically and seeing it documented in front of her were two different experiences, she photographed the certificate in the wedding portrait with her highresolution camera, then began searching the historical society’s database for any additional records related to William and Sarah.

The groom’s full name was listed as William Brennan, occupation cotton merchant.

The bride was Sarah Elizabeth Parker before marriage.

The database search yielded several documents.

William Brennan had been a prominent figure in Charleston’s business community, his name appearing in shipping manifests, business partnerships, and society pages.

He had been married once before.

His first wife had died in 1881, 2 years before his marriage to Sarah.

No children from the first marriage were recorded.

Sarah’s family history was harder to trace.

The Parkers had been small land owners, their fortunes declining after the Civil War, like so many southern families.

Rebecca found Thomas Parker, likely Sarah’s father, listed in debt proceedings from 1882.

He had owed significant money to several Charleston merchants, including William Brennan.

Rebecca leaned back in her chair, a disturbing picture forming.

A wealthy widowerower, a family in debt, and a 13-year-old girl.

She had studied enough 19th century social history to recognize the pattern.

Marriage had often been used as an economic transaction, especially in the South during the difficult reconstruction period.

But understanding it intellectually didn’t make it easier to accept emotionally.

She pulled up census records.

The 1880 census showed Sarah Parker living with her parents and four siblings.

She would have been 10 years old.

By the 1885 census, she was listed as Sarah Brennan, living in Williams household with no children yet recorded.

She would have been 15.

Rebecca continued searching, finding property records that showed William had forgiven Thomas Parker’s debts in early 1883, just months before the wedding.

The transaction was clear.

Sarah had been given to William as payment, her childhood traded for her family’s financial survival.

As the afternoon faded into evening, Rebecca couldn’t stop looking at the wedding photograph.

Sarah’s face haunted her.

That frozen expression that she now understood wasn’t shyness or formality, but fear.

This child had known what was happening to her, had understood she was being sold, and there had been nothing she could do about it.

Rebecca decided she needed to know what happened to Sarah after that wedding day.

Did she survive? Did she escape? Did anyone try to help her? Rebecca returned to the estate donation boxes the next morning, searching methodically through every envelope and folder.

Near the bottom of the third box, she found a small bundle of letters tied with faded ribbon.

The return address on several envelopes showed Mrs.

Katherine Parker Miller, Richmond, Virginia.

Katherine Parker Miller, Rebecca checked her notes.

That was Sarah’s older sister who had married and moved to Virginia before Sarah’s wedding.

The letters were addressed to Catherine from various correspondents, and Rebecca’s hands trembled slightly as she untied the ribbon and began reading.

The first letter was dated July 1883, just one month after Sarah’s wedding.

It was written in a young, uncertain hand.

Dear Catherine, I hope this letter finds you well.

I miss you terribly.

The house is very large, and I’m often alone.

William is kind enough when he is home, but he works very long hours.

Mother says I should be grateful for my fine circumstances, but I confess I am lonely.

Please write to me soon.

Your loving sister Sarah.

The letter’s careful politeness couldn’t quite hide the loneliness beneath.

Rebecca imagined a 13-year-old girl alone in a large house, trying to be the wife of a man nearly three times her age, having no idea how to navigate her new role.

The next letter, dated October 1883, was more distressing.

Dear Catherine, I received your last letter, and it gave me such comfort.

You asked if I am happy.

I try to be.

William says I must learn to manage the household properly, but I make so many mistakes.

The servants correct me, which is humiliating.

I’m not used to giving orders to adults.

Sometimes I forget I’m supposed to be the mistress of the house and not a child anymore.

William grows impatient with my failures.

I wish you could visit.

Rebecca felt her throat tighten.

Sarah had been expected to run a household, manage servants, and be a proper wife, all while barely past childhood herself.

The weight of adult responsibilities had been dropped on her shoulders without preparation or support.

A letter from March 1884 revealed a new development.

Catherine, I must tell you what I cannot tell, mother.

I’m with child.

The doctor confirmed it last week.

I’m frightened.

I know I should be joyful, but I’m only 14, and I do not know how to be a mother when I still feel like a child myself.

William is pleased, which is a relief.

Perhaps once the baby comes, things will be better.

Rebecca set the letter down, fighting back tears.

14 years old and pregnant.

In the modern world, this would be considered a crime.

In 1884, Charleston, it had been perfectly legal, even expected.

Rebecca knew she needed to understand what had happened to Sarah medically.

Pregnancy and child birth in the 19th century were dangerous for women of any age.

But for a 14-year-old child, the risks would have been significantly higher.

She contacted Dr.

Jennifer Washington, a colleague who specialized in historical medicine and women’s health.

They met at a coffee shop near the Medical University of South Carolina, where Dr.

Washington taught.

Rebecca showed her copies of Sarah’s letters and the timeline she had constructed.

Dr.

Washington’s expression grew increasingly grave as she read.

A 13-year-old bride pregnant at 14, Dr.

Washington said quietly.

Her body wouldn’t have been physically mature enough for pregnancy.

The risks of complications, obstructed labor, hemorrhage, infection, would have been substantial.

Did she survive the birth? I don’t know yet, Rebecca admitted.

That’s what I’m trying to find out.

I was hoping you might help me locate medical records if any exist.

Doctor Washington explained that detailed medical records from the 1880s were rare, but death certificates, hospital admissions, and physicians journals sometimes survived.

She offered to search the medical archives while Rebecca continued her documentary research.

Meanwhile, Rebecca had requested access to local newspaper archives from 1884 and 1885.

Victorian newspapers often carried birth and death announcements for prominent families, and William Brennan’s status as a cotton merchant meant his household would have been newsworthy.

She found the announcement she was looking for in the Charleston Daily News, dated November 1884.

Born to Mr.

and Mrs.

William Brennan, a son, November 12th, 1884.

Mother and child reported in fair condition.

Sarah would have been barely 15 years old.

Rebecca continued searching and found two more birth announcements, a daughter born in August 1886 and another son in January 1888.

Three children before Sarah turned 18.

The physical and emotional toll must have been overwhelming.

Dr.

Washington called 3 days later with disturbing news.

She had found records at the Medical College of South Carolina indicating that Sarah had been admitted multiple times for various ailments between 1884 and 1889.

The physician’s notes written in the detached clinical language of the era described nervous exhaustion, melancholia, and weakness following childbirth.

One note from 1887 was particularly troubling.

Mrs.

Brennan, age 17, admitted with severe bruising to the arms and face.

Patient claims to have fallen downstairs.

Husband reports wife has become increasingly clumsy and inattentive.

Recommended rest and fortifying tonics.

Rebecca felt sick.

The physician had either failed to recognize or chosen to ignore signs of domestic violence.

A 17-year-old covered in bruises, and the doctor had accepted the husband’s explanation without question.

Rebecca’s investigation took an unexpected turn when she discovered a collection of depositions from a legal case filed in 1889.

The case had been brought by Katherine Miller, Sarah’s sister, attempting to gain custody of Sarah’s three children after Sarah’s death.

Sarah had died.

Rebecca’s hands shook as she read the legal documents.

The death certificate listed the date as March 15th, 1889.

Sarah had been 21 years old.

The cause of death was recorded as complications following childirth and subsequent infection.

But it was the witness depositions that revealed the fuller, more terrible story.

Catherine had called several of the Brennan’s neighbors and former servants to testify about the conditions of Sarah’s life and the circumstances of her death.

A former housemmaid named Martha testified Mrs.

Brennan was just a child when she came to that house.

She tried her best, but Mr.

Brennan expected her to be a full- grown woman from the start.

He was harsh with her when she made mistakes, which was often because how could a 13-year-old know how to run a household? I saw him strike her more than once.

I wanted to help, but I needed the position, and who would listen to a servant anyway? A neighbor, Mrs.

Elizabeth Hammond, provided even more damning testimony.

I called on Mrs.

Brennan several times in the early years of her marriage.

She was so young, so obviously overwhelmed.

After her first child was born, she seemed to age rapidly, not in years, but in spirit.

The light went out of her eyes.

I invited her to church socials and afternoon teas, but Mr.

Brennan rarely permitted her to attend.

He said she needed to focus on her household duties and children.

By the time she was 19, she looked exhausted beyond her years.

The family physician, Dr.

Henry Morrison, had also been deposed.

His testimony was clinical but revealing.

I attended Mrs.

Brennan through three pregnancies and child births.

Each was difficult due to her age and physical immaturity when the pregnancies began.

After the third birth in January 1889, she developed child bed fever.

I recommended hospital treatment, but Mr.

Brennan preferred to keep her at home.

By the time I was called back a week later, the infection had progressed too far.

She died within days.

Rebecca read the testimony multiple times, anger building with each reading.

Sarah had needed hospital care, and her husband had refused it.

Whether through ignorance, stubbornness, or something darker, William Brennan’s decision had directly contributed to his young wife’s death.

The custody case revealed one final heartbreaking detail.

Catherine’s petition included a statement from Sarah herself, written shortly before her death and witnessed by Dr.

Morrison.

In a shaky hand, Sarah had written, “I fear I will not recover from this illness.

If I die, I beg that my children be placed in the care of my sister, Catherine.

She will love them and protect them in ways I was never protected.

The custody case documents revealed that Catherine’s petition had been denied.

Despite the testimony about Williams treatment of Sarah, despite Sarah’s own written wish, the court had ruled that the children should remain with their father.

The judge’s opinion stated that a father’s natural right to his children cannot be superseded, except in cases of demonstrated moral unfitness.

And while Mr.

Brennan may have been a stern husband, there is no evidence that he would be an inadequate father.

Rebecca traced what happened to Sarah’s three children through subsequent records.

The eldest son, named William after his father, appeared in military records.

He had enlisted in the army at age 16 in 1900 and had died in the Philippines during the SpanishAmerican War.

He had been 17 years old.

The daughter, Catherine, named for Sarah’s sister, had married at age 15 in 1901 to a man 30 years her senior.

The parallel to her mother’s life was chilling.

Rebecca found Catherine’s death certificate from 1910.

She had died at age 24.

Cause of death listed as consumption.

She had left behind four children.

The youngest son, Thomas, had run away from home at age 14, according to a police report filed in 1902.

There was no record of him after that.

He had simply vanished into history.

Perhaps escaping the pattern that had destroyed his mother and sister.

Perhaps meeting some other unfortunate fate.

William Brennan had remarried in 1891, just 2 years after Sarah’s death.

His new wife was 22 years old, nearly the same age Sarah had been when she died.

This marriage produced no children, and William himself died in 1905 at age 59, a relatively wealthy and respected member of Charleston society.

His obituary made no mention of Sarah, referring to his second wife as his beloved companion, and mentioning his surviving children only in passing.

Rebecca sat in the archives, surrounded by documents that painted a devastating picture.

Sarah had been married at 13, pregnant at 14, and dead at 21 after years of what the evidence strongly suggested was abuse and neglect.

Her children had inherited her trauma, one dead in war, one repeating her mother’s pattern of child marriage and early death, one disappeared entirely.

And William Brennan, the man who had essentially purchased a child as his wife, who had impregnated her when she was barely past puberty, who had denied her medical care when she was dying, he had lived comfortably and died respected, his reputation intact.

The injustice of it burned in Rebecca’s chest.

This wasn’t just historical curiosity anymore.

This was a story that needed to be told, a truth that needed to be acknowledged.

Sarah had died voiceless and forgotten.

But Rebecca could give her a voice now more than a century later.

To understand how Sarah’s tragedy had been allowed to happen, Rebecca needed to understand the legal framework of 1883 South Carolina.

She reached out to Professor David Richardson, a legal historian at the University of South Carolina who specialized in 19th century marriage law.

They met in his office surrounded by law books and historical documents.

Rebecca explained Sarah’s case and Professor Richardson nodded with grim recognition.

Unfortunately, this story isn’t unusual for the period.

He said, “Child marriage was legal in every state in 1883.

South Carolina didn’t set a minimum age for marriage with parental consent until 1895, and even then, it was only set at 12 years old.

” Rebecca felt nauseated.

12 years old was considered old enough to marry on paper.

Yes.

In practice, marriages of girls under 14 were less common than between 14 and 16.

But they certainly happened, especially in circumstances like Sarah’s, families in financial distress, wealthy men looking for young wives.

The law didn’t protect these girls because they weren’t seen as needing protection.

They were seen as their father’s property until marriage, then their husband’s property after.

Professor Richardson pulled out several legal texts from the 1880s, showing Rebecca the laws governing marriage, property rights, and domestic relations.

Under South Carolina law in 1883, a married woman had almost no legal rights.

She couldn’t own property in her own name, couldn’t enter into contracts, couldn’t leave her husband without his permission.

If she tried to flee domestic violence, the law authorized her husband to forcibly retrieve her.

“What about the age difference?” Rebecca asked.

Wasn’t there any legal concern about a 37-year-old man marrying a 13-year-old? Not in legal terms.

No.

Age of consent laws existed, but they typically applied only to sexual relations outside of marriage.

Once a girl was married, no matter her age, her husband had unlimited sexual access to her.

The concept of marital rape didn’t exist in law.

A husband could not legally rape his wife because her consent was presumed permanent as part of the marriage contract.

Rebecca thought of Sarah, pregnant at 14.

Under the law, there had been nothing wrong with what William had done to her.

It had been his legal right.

Professor Richardson showed her court cases from the era where women had attempted to escape violent marriages.

Most had been unsuccessful.

Judges routinely ruled that a husband’s authority over his wife was absolute and that wives needed to submit to their husband’s discipline.

Even in cases of severe abuse, courts hesitated to intervene in the private sphere of marriage.

What about the children? Rebecca asked.

Catherine tried to get custody after Sarah died.

Why did she fail? paternal rights were absolute, Richardson explained.

The father’s claim to his children was nearly impossible to overturn.

The court would have needed clear evidence that William was actively harming the children, not just that he had been a harsh husband to their mother.

And remember, harsh treatment of wives wasn’t considered morally problematic by most judges of that era.

Rebecca left the meeting feeling even more troubled than before.

Sarah’s tragedy wasn’t an aberration or the result of one cruel man.

It was a systemic failure sanctioned by law and social custom that had allowed countless girls to be married off as children and subjected to what would now be recognized as statutory rape, domestic violence, and reproductive coercion.

Rebecca knew she needed to find Sarah’s living descendants.

Someone in the present day should know what had happened to their ancestor, should have the opportunity to honor her memory and understand her story.

She began with the genealogical records she had already compiled.

Sarah’s daughter, Katherine, who had died in 1910, had left four children.

Rebecca traced their lineage through census records, marriage certificates, and death certificates, building a family tree that extended into the present day.

After weeks of research and several false leads, she found a living great great-granddaughter named Jennifer Parker, a teacher living in Columbia, South Carolina.

Rebecca sent a carefully worded email explaining who she was and that she had discovered documents related to Jennifer’s ancestor, Sarah Brennan.

She didn’t include details about Sarah’s age at marriage, wanting to explain the situation sensitively in person if Jennifer was interested in learning more.

Jennifer responded within hours.

I’m fascinated by family history and would love to know more about Sarah.

My grandmother mentioned her once, saying, “She died very young, but we never knew details.

When can we meet?” They arranged to meet at a cafe in Colombia the following Saturday.

Rebecca brought copies of the wedding photograph, letters, legal documents, and medical records organized in a folder, but not yet displayed.

She wanted to gauge Jennifer’s readiness for what she was about to learn.

Jennifer arrived promptly.

A woman in her late 30s with curly dark hair and an eager open expression.

“I’ve been researching our family tree for years,” she said as they settled at a corner table.

“But I’ve never been able to find much about Sarah.

She’s like a ghost in our family history.

We know she existed, but not who she was.

” Rebecca took a deep breath.

“I need to prepare you.

What I’ve discovered about Sarah is difficult.

Her life was very hard, and what happened to her was tragic.

” I Jennifer’s expression grew serious.

Tell me, she’s my ancestor.

She deserves to have her story known, whatever it is.

Rebecca opened the folder and showed Jennifer the wedding photograph first.

Jennifer looked at it, smiling at first, then her smile fading as she studied the image more closely.

She looks so young, Jennifer said slowly.

How old was she? 13, Rebecca said quietly.

She was 13 years old when she married William Brennan.

He was 37.

The color drained from Jennifer’s face.

She stared at the photograph, then looked up at Rebecca.

13? That’s That’s the same age as my daughter.

Her hand went to her mouth.

Rebecca spent the next hour taking Jennifer through what she had discovered, the financial transaction that had led to the marriage, Sarah’s letters revealing her loneliness and fear, the three pregnancies before age 18, the medical records suggesting abuse, and finally, her death at 21 from an infection that should have been treated in a hospital.

Jennifer wept as she read Sarah’s letters.

She was just a child, a frightened child who was sold to a man and then died because of it.

After their meeting, Jennifer became Rebecca’s partner in ensuring Sarah’s story was told properly and respectfully.

Together, they planned how to bring Sarah’s experience to public attention in a way that honored her memory while also educating people about the realities of child marriage, both historical and contemporary.

Jennifer contacted other descendants from Sarah’s line, explaining what had been discovered.

Most were shocked and disturbed, having had no idea of the circumstances of Sarah’s life and death.

Several agreed to participate in creating a memorial project that would ensure Sarah was remembered not just as a name in a family tree, but as a real person whose suffering deserved acknowledgement.

Rebecca proposed that the Charleston Historical Society create an exhibition about child marriage in 19th century South Carolina, using Sarah’s story as the central case study.

The society’s director, initially hesitant about such a difficult topic, was convinced when Jennifer and other descendants agreed to loan family documents and participate in the exhibition’s development.

The exhibition, titled Stolen Childhood: The Reality of Child Marriage in Victorian Charleston, opened six months later.

It featured Sarah’s wedding photograph prominently along with her letters, medical records, and legal documents.

But it also provided broader context, showing that Sarah’s experience, while extreme, was part of a larger pattern of child marriages throughout the South during the Reconstruction era and beyond.

Rebecca had researched statistics for the exhibition in South Carolina between 1880 and 1900.

Approximately 15% of girls were married before age 16, with some as young as 10 or 11.

The practice was most common in families experiencing financial hardship where daughters were seen as economic burdens that could be converted into advantageous alliances through marriage.

The exhibition also included contemporary context.

Rebecca had discovered that child marriage was still legal in South Carolina.

The minimum age was 16 with parental consent, but judicial approval could allow marriages for younger children in exceptional circumstances.

Nationally, thousands of American children were still being married each year in the 2020s, often in situations involving significant age gaps and pressure from family or religious communities.

Jennifer spoke at the exhibition’s opening, standing beside the enlarged wedding photograph of her ancestor.

Looking at Sarah’s face, “I see my own daughter,” she said to the assembled crowd.

“I see a child who should have been playing, learning, growing, not being forced into marriage and motherhood.

” Sarah died over 130 years ago.

But her story isn’t just history.

Girls are still being married as children today, still being denied their childhood and their choices.

By remembering Sarah, by refusing to let her suffering be forgotten, we honor her and we commit ourselves to protecting the children who still need protecting.

The exhibition drew significant media attention.

Local newspapers ran stories about Sarah’s case, and several advocacy organizations focused on ending child marriage reached out to use Sarah’s story in their educational materials.

The photograph that had seemed merely old-fashioned when Rebecca first discovered it had become a powerful symbol of a practice that many people had assumed was purely historical.

The exhibition remained at the Charleston Historical Society for 6 months.

And during that time, more than 15,000 people visited.

Teachers brought school groups.

Social workers came to better understand historical trauma.

And many visitors simply stood before Sarah’s wedding photograph, seeing it with new eyes.

No longer a quaint Victorian portrait, but evidence of a legal injustice.

Rebecca received numerous letters from visitors.

Some shared their own family stories of ancestors who had been married as children.

Others wrote about contemporary experiences.

A woman who had been married at 15 to a man in his 30s, a social worker who had fought to prevent child marriages and immigrant communities.

A legislator who vowed to work on raising the minimum marriage age in South Carolina.

One letter particularly moved Rebecca.

It came from a woman in her 70s who wrote, “My grandmother was married at 13 in 1895.

Just like Sarah, she never talked about her early life, but I remember her eyes.

There was such sadness there.

She died when I was young, and I never understood what that sadness meant.

Now I do.

Thank you for helping me understand her life and for making sure stories like hers are not forgotten.

Jennifer worked with child protection advocates to establish the Sarah Brennan Memorial Fund, which supported organizations working to end child marriage both in the United States and internationally.

The fund also provided educational resources about the history of child marriage and its continued impact on families and communities.

For Rebecca, the investigation had transformed her understanding of her work as an archavist.

She had always believed that historical documents were important, but Sarah’s case had shown her that they could be powerful tools for justice, not just recording the past, but illuminating it in ways that demanded recognition and change.

She continued to research other cases from the society’s archives, finding more stories of young brides, some who had survived and adapted, others who had not.

Each story added depth to the understanding of how gender, age, economics, and law had intersected to create systemic vulnerability for girls in the 19th century.

The wedding photograph remained on permanent display at the historical society, relocated after the temporary exhibition ended to a gallery focused on women’s history.

The caption Rebecca wrote for it read, “Sarah Parker Brennan, married at age 13 in 1883, died at age 21 in 1889.

” This photograph represents both a personal tragedy and a systemic failure.

The legal and social structures that permitted children to be married and subjected to adult responsibilities and vulnerabilities they were not prepared to handle.

Sarah’s story reminds us that the past is not simply distant history, but a foundation for our present, and that we honor those who suffered by working to ensure such suffering is not repeated.

Visitors still paused before the photograph, studying Sarah’s young face and seeing what they had not seen before.

Not a bride, but a child.

That recognition, Rebecca believed, was essential.

As long as people could look at that image and understand what it truly represented, Sarah’s experience would not have been entirely in vain.

The photograph, with its impossible truth now visible to anyone willing to look closely, continued to do what photographs do best.

It preserved a moment in time, held it up for examination, and forced viewers to confront what they might otherwise prefer not to see.

Sarah’s wedding day, captured in silver and chemistry over a century ago, had become a window into both past injustice and present responsibility, a reminder that every generation must choose whether to perpetuate or challenge the systems that harm the most vulnerable.

And in that choice, in that ongoing commitment to protection and justice, Sarah’s memory lived on, not just as a victim of her time, but as a call to action for all times that followed.

News

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

This 1904 wedding portrait looks elegant — until you see what the groom is hiding

This 1904 wedding portrait looks elegant until you see what the groom is hiding. The afternoon sun filtered through the…

It was just an old photo from 1912 — until experts zoomed in and were shocked

It was just an old photo from 1912 until experts zoomed in and were shocked. The Chicago History Museum’s acquisition…

It was a portrait of love — until you look closely at the mother’s hands

It was a portrait of love until you look closely at the mother’s hands. The afternoon light filtered through dusty…

This 1899 portrait of a mother and daughter appears peaceful — until you zoom in on the child’s eyes

This 1899 portrait of a mother and daughter looks peaceful until you notice what’s hidden in the child’s eyes. The…

This 1899 family portrait was restored, and a secret was only revealed now

This 1899 family portrait was restored, and a secret was only revealed now This 1899 family portrait was restored, and…

End of content

No more pages to load