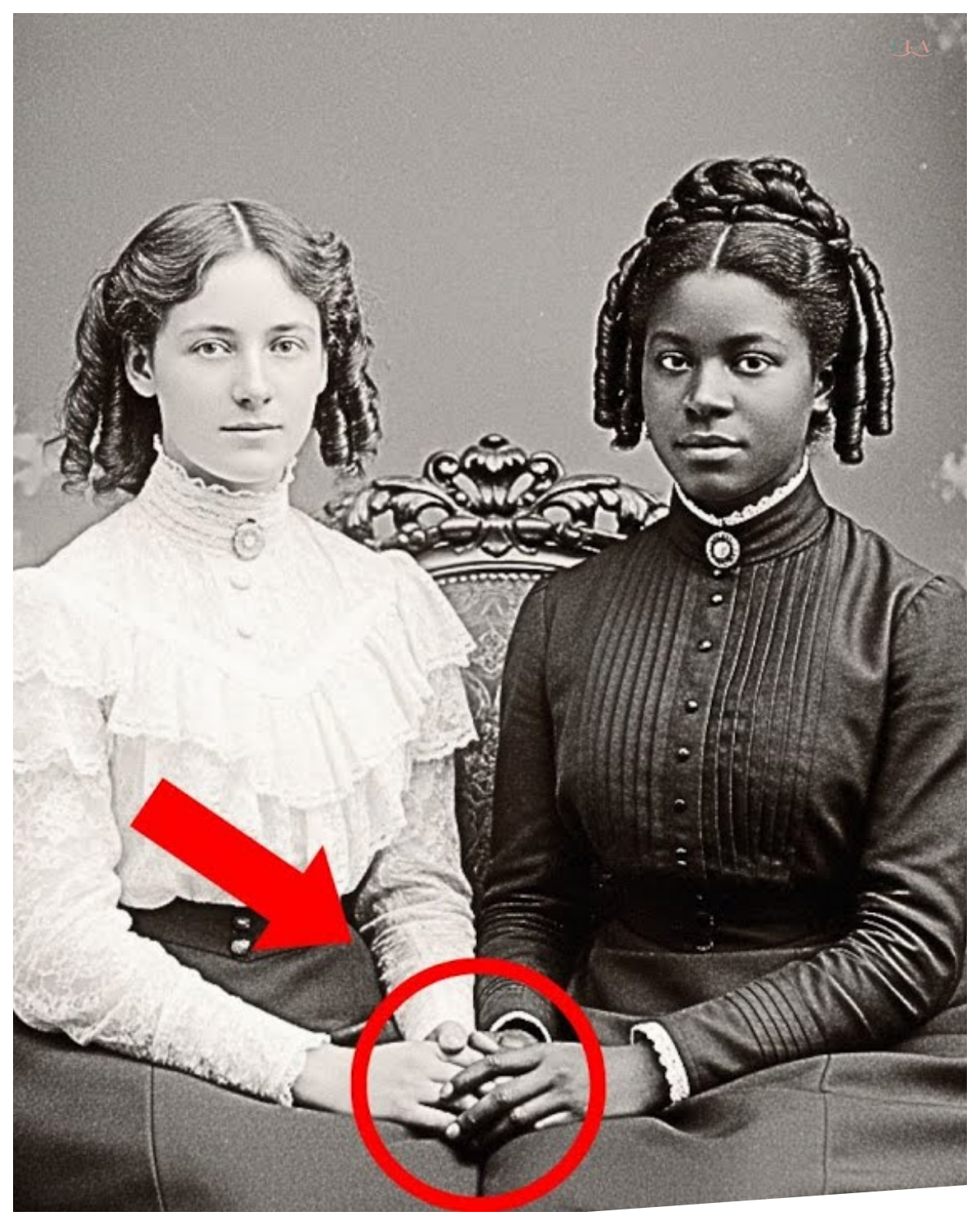

It Was Just a Studio Photo of Two friends — But Look Closely at What They’re Holding in Their Hands

It was just a studio photo of two young women, but look closely at what they’re holding in their hands.

The photograph arrived at the Georgia Historical Archive in a donation box from a recently closed antique shop in downtown Atlanta.

Among dusty picture frames and forgotten trinkets, archavist Lauren Mitchell found it tucked inside a cracked leather portfolio, a studio portrait from 1895, surprisingly well preserved despite its age.

Lauren carefully removed the photograph and placed it under her desk lamp.

The image showed two young women, both appearing to be 16 or 17 years old, seated side by side on an ornate Victorian sati.

What immediately struck Lauren was their positioning, a white girl and a black girl, sitting together in a formal studio portrait during an era when such photographs were virtually unheard of in the South.

The white girl wore a high-colored white blouse with delicate lace trim, her light hair pulled back in the Gibson girl style popular at the time.

The black girl wore a similar blouse, equally elegant, her hair styled with careful attention.

But what truly captured Lauren’s attention was their hands.

They were holding each other’s hands, fingers intertwined in a gesture of unmistakable friendship and solidarity.

Lauren had worked at the archive for 12 years, processing thousands of historical photographs.

She understood the significance of what she was seeing.

In 1895, Georgia, just 30 years after the Civil War, the South was deep in the Jim Crow era.

Segregation laws were being aggressively enforced.

Interracial friendships were not just discouraged, they were dangerous.

for two teenage girls to pose together this way in a professional studio suggested something extraordinary.

She reached for her magnifying glass and examined the photograph more closely.

The studio’s mark was embossed in the lower right corner.

Whitmore Photography, Atlanta, 1895.

She made a note to research the studio later.

As she scanned across the image, studying the girl’s faces, both solemn and determined, as was customary for photographs of that era, her attention was drawn to their free hands.

Each girl held something small resting in her palm.

Lauren adjusted her lamp and leaned closer.

They appeared to be identical objects, circular, possibly made of metal.

Metals, coins.

She couldn’t quite make out the details with the naked eye.

The photograph would need to be scanned at high resolution.

Lauren felt the familiar thrill of discovery coursing through her.

This wasn’t just an unusual photograph.

This was a mystery, and somewhere in this fading image lay a story that had been waiting 129 years to be told.

Lauren spent her lunch break setting up the highresolution scanner in the archives digitization lab.

The photograph lay flat on the scanner bed, secured with archival corner mounts to prevent any damage.

She adjusted the settings to capture the maximum detail, 3200 dots per inch, full color spectrum preservation, multiple exposure bracketing to account for the images age and fading.

The scanner hummed softly as its light bar traveled across the photograph.

Lauren watched the preview screen as the digital file emerged pixel by pixel, revealing textures and details impossible to see with the naked eye.

The process took nearly 30 minutes, but the result was extraordinary.

A massive digital file containing every minute detail of the original image.

She opened the file in her professional imaging software and immediately zoomed to 600% magnification, focusing on the objects in the girl’s hands.

Now she could see them clearly.

They were medallions roughly 2 in in diameter, appearing to be made of bronze or copper.

Each medallion hung from a delicate chain visible between the girl’s fingers.

Lauren increased the magnification to 1,000% and adjusted the contrast in sharpness.

The medallion’s surfaces came into focus and her breath caught in her throat.

They were intricately engraved with symbols, a book, an oil lamp, and what appeared to be two hands clasped together.

Around the edge of each medallion ran a circle of tiny letters or numbers too small to read even at this magnification.

She saved the image and opened it in specialized enhancement software used for forensic photography analysis.

Applying various filters, edge detection, frequency separation, unsharp masking, she gradually brought the tiny inscriptions into clarity.

The letters formed words, though in Latin ciia illuminate at the top, and beneath the central symbols, a series of numbers 33.

7490 84.

380.

Lauren grabbed her notebook and quickly wrote down everything she could see.

The Latin phrase translated to knowledge illuminates.

The numbers looked like coordinates, latitude and longitude.

She opened a mapping program on her computer and entered the coordinates.

The location marked was in Atlanta in what was now the sweet Auburn historic district.

Though in 1895, it would have been part of the city’s developing black neighborhood.

The specific point fell on a street corner where, according to current maps, an old church building still stood.

Lauren sat back in her chair, her mind racing.

The medallions weren’t mere friendship tokens or simple jewelry.

They were encoded with information deliberately designed to carry a message.

But what message? And why would two teenage girls in 1895 Atlanta need to hide information in such an elaborate way? She zoomed out to examine the girls faces again, studying their expressions with new understanding.

Their solemn gazes now seemed less like photographic convention and more like determination.

Lauren spent the afternoon researching Whitmore Photography.

The studio had operated in Atlanta from 1889 to 1903, owned by a man named Albert Whitmore.

According to city directories and newspaper archives, Whitmore had been known for portrait work, particularly of Atlanta’s emerging black middle class, an unusual specialty for a white photographer in that era.

She found an obituary from 1904 in the Atlanta Constitution.

Albert Whitmore, respected photographer and businessman, passed away at age 52.

Mr.

Whitmore was known for his progressive views and his commitment to documenting all of Atlanta’s citizens with equal dignity.

The phrasing was careful, almost coded, suggesting Whitmore’s work had been controversial.

Lauren contacted the Atlanta History Center, knowing they maintained extensive collections of old business records.

By late afternoon, a colleague named Marcus had located three ledger books from Whitmore Photography preserved in their archives.

He agreed to scan the relevant pages and send them to her immediately.

The scanned ledgers arrived in her email an hour later.

Lauren opened the files and began searching through the handwritten entries.

Whitmore had documented each sitting.

Client names, dates, payment amounts, and brief notes about the photographs.

The entries from 1895 filled several pages, and Lauren scrolled through them carefully, looking for anything that might reference the two girls.

Then she found it.

August 12th, 1895.

Portrait sitting.

Miss Katherine Henderson and Miss Sarah Williams.

Payment rendered in full.

Special request for privacy.

No display in studio window.

Note, two copies ordered, small format, additional engraving work on tokens included in commission.

Lauren leaned closer to the screen.

So, the girls names were Katherine Henderson and Sarah Williams, and Whitmore had done engraving work on tokens.

He had created the medallions himself, or at least engraved them.

The request for privacy and the prohibition against displaying the photograph in the studio window suggested the girls, or their families, knew how controversial this image would be.

She immediately began searching census records, starting with the 1900 federal census for Atlanta.

Finding Katherine Henderson proved difficult.

Henderson was a common name, but she located several possibilities.

All white families living in various Atlanta neighborhoods.

Sarah Williams was even more challenging.

There were dozens of Sarah Williams entries in the black community.

Lauren needed more specific information.

She returned to the photograph, zooming in on other details she might have missed.

The girls clothing, while similar in style, showed subtle differences in quality and fabric that might indicate their family’s economic circumstances.

The seti they sat on was expensive, suggesting the studio’s better furnishings.

This was not a budget portrait.

Then Lauren noticed something she had overlooked before.

A small pin on Catherine’s collar, barely visible even in the high resolution scan.

She enhanced the area and saw what appeared to be a school emblem or insignia.

She could make out partial letters, AFS.

Lawrence spent the next morning researching Atlanta schools from the 1890s.

The initials AFS proved difficult to trace.

Most school records from that era had been lost or destroyed.

She contacted Dr.

Raymond Parker, a retired history professor from Emory University who had written extensively about post Civil War education in Georgia.

Dr.

Parker called her back within an hour, his voice excited.

EFS could be Atlanta Female Seminary.

It operated from 1881 to 1897, located on Peach Tree Street.

It was a private school for girls from wealthy families, all white, of course, as was legally required.

But there were rumors about that school, things that were never officially documented.

“Oh, what kind of rumors?” Lauren asked, already taking notes.

That the head mistress, a woman named Eliza Foster, was an abolitionist sympathizer who continued to harbor progressive views even after the war.

There were whispers that she secretly taught black girls in the evenings, using the school’s facilities after the white students had gone home.

Nothing was ever proven, and the school closed suddenly in 1897 amid some kind of scandal that the newspapers of the time declined to elaborate on.

Lauren felt her pulse quicken.

Would there be any records, student rosters, administrative documents? Dr.

Parker was quiet for a moment.

The school’s records were supposedly destroyed in a fire in 1898, but I know Foster’s great great granddaughter.

She lives here in Atlanta, and she’s mentioned having some family papers.

Her name is Virginia Foster Chen.

I can reach out to her if you’d like.

Please, Lauren said.

This could be important.

Two days later, Lauren found herself sitting in Virginia Chen’s living room in the Virginia Highland neighborhood.

Virginia was a woman in her 70s, a retired librarian with sharp eyes and an obvious passion for family history.

She had laid out several boxes of documents on her dining room table.

“My great great-grandmother Eliza was a remarkable woman,” Virginia said, carefully opening one of the boxes.

“She believed education was a fundamental right, regardless of race or gender.

” In the 1890s, that belief could get you killed in Atlanta.

She pulled out a leatherbound journal, its pages yellowed, but still intact.

This was Eliza’s private diary.

She never published it, and the family kept it hidden for generations.

I think you’ll find it illuminating.

And Lauren opened the journal carefully.

The entries were written in elegant cursive, dated from 1881 to 1897.

She turned to August 1895, and began reading.

Today I did something that could destroy everything I have built.

But I could not live with myself if I had refused.

Katherine Henderson and Sarah Williams asked permission to have their photograph taken together to commemorate their graduation from our secret evening academy.

I arranged the sitting with Albert Whitmore, whom I trust implicitly.

These two brilliant young women have studied together for four years, learning literature, mathematics, science, and philosophy side by side.

They have proven that the artificial barriers society erects mean nothing in the pursuit of knowledge.

Virginia made tea as Lauren continued reading through Eliza Foster’s journal.

The entries painted a picture of extraordinary courage and careful planning.

The Evening Academy had begun in 1882, just one year after the Atlanta Female Seminary opened its doors to white students.

Eliza wrote, “I cannot in good conscience educate only those whom society deems worthy while denying knowledge to others equally capable.

Thus begins our dual mission.

By day, the seminary will serve its official purpose.

By night, we will serve truth.

The system Eliza developed was elaborate and risky.

She recruited four other teachers who shared her convictions.

All unmarried women who lived on the school premises and could control access to the building.

White students attended classes from 8:00 in the morning until 3:00 in the afternoon.

After they left, Eliza and her teachers would wait 2 hours, ensuring complete privacy before admitting their evening students through a back entrance that faced an alley.

The Evening Academy served black girls from families in Atlanta’s emerging professional class.

Daughters of ministers, teachers, business owners, and tradesmen who desperately wanted their children educated but were barred from white schools and found the available black schools inadequate or inaccessible.

Class sizes were kept deliberately small, never more than 12 students at a time to minimize risk and maintain secrecy.

Lauren found an entry from September 1891 that mentioned both Katherine and Sarah by name.

Two new students joined us tonight.

Katherine Henderson, daughter of a railroad clerk, referred by her mother, who worked briefly as our day school seamstress and learned of our evening work.

Sarah Williams, daughter of Benjamin Williams, the printer.

Both girls are 13 years old and hungry for learning.

I see great potential in them both.

The journal documented four years of their education together.

Eliza noted their progress in various subjects, their friendship, and their growing awareness of the dangerous nature of what they were doing.

In one entry from 1893, Eliza wrote, “Catherine and Sarah have begun to understand that knowledge brings both power and peril.

They asked me today what would happen if we were discovered.

” I answered, “Honestly, I would likely be arrested.

My teachers would lose their positions, and the students and their families would face violence.

Yet, none of us can stop.

Some truths are worth the risk.

” Virginia pointed to a box she hadn’t yet opened that contains letters between my great great grandmother and the families of her evening students that correspond in code using book ciphers and substitutions.

Even in private correspondence they couldn’t risk explicit discussion of what they were doing.

Lauren opened the letter box and found dozens of carefully preserved envelopes.

She selected one dated August 1895 addressed to Mrs.

Henderson.

The letter was brief.

Your daughter has completed her studies with exceptional distinction.

The token we discussed has been prepared and will be presented at the ceremony.

May it serve its intended purpose should the need arise.

The tokens, Lauren said, looking up at Virginia.

The medallions in the photograph.

Eliza arranged for them to be made.

Virginia nodded.

Graduation gifts, but also something more practical, I suspect.

Lauren returned to the archive the next morning with photographs of key pages from Eliza Foster’s journal, which Virginia had permitted her to document.

She immediately pulled up the coordinates engraved on the medallions.

33.

749084.

3880.

The location in Sweet Auburn was specifically at the corner of Auburn Avenue in Bell Street, where an old church building still stood.

She researched the building’s history through property records and historical maps.

In 1895, the structure had been Bethl African Methodist Episcopal Church, a cornerstone of Atlanta’s black community.

The church had been built in 1887 and served not just as a place of worship, but as a community center, school, and meeting place for civic organizations.

Lauren found a reference librarian position listing from 1896 in an old church newsletter preserved on microfilm.

Miss Sarah Williams, recent graduate of private study, will be assisting Reverend Thomas with our Sunday school program and weekday tutoring sessions.

The congregation welcomes her service.

So Sarah had returned to her community and immediately begun teaching.

But what about Catherine? Lauren searched through city directories and census records, finally finding a Katherine Henderson listed in the 1900 census as a private tutor living in a boarding house on the edge of Atlanta’s fourth ward, an area that was becoming increasingly integrated despite segregation laws.

She cross referenced addresses and found something remarkable.

Catherine’s boarding house was only three blocks from Bethl Ame Church.

The two young women had stayed close, continuing to work in parallel, even though society demanded they live separate lives.

Lauren decided to visit the current Bethl AM church, which still operated in the same building, though it had been renovated multiple times over the decades.

She called ahead and spoke with the church secretary, explaining her research.

The secretary connected her with Deacon Morris, an elderly man who had been a member of the church for over 60 years and served as an unofficial historian.

Deacon Morris met Lauren at the church on a quiet Wednesday afternoon.

He was 84 years old with white hair and kind eyes that sparkled with intelligence.

He walked her through the building, pointing out original architectural features that remained despite the renovations.

“This church has always been more than a church,” he said as they descended stairs to the basement level.

“During Jim Crow, when black folks couldn’t get proper education, we provided it here.

Before integration, when meeting in mixed groups was dangerous, this basement saw many secret gatherings of people who believed in equality.

The basement was now used for storage and fellowship events.

But Deacon Morris led Lauren to a back corner where old furniture and boxes were stacked.

We found something about 20 years ago when we were renovating.

Nobody knew quite what to make of it, so we just kept it safe.

He pulled a wooden crate from behind a stack of chairs and opened it carefully.

Inside were dozens of the same medallions Lauren had seen in the photograph, all identical, all engraved with the same symbols and coordinates.

Beneath the medallions lay a ledger book, its cover bearing the title Evening Academy graduates 1882 1897.

Lauren’s hands trembled as she carefully opened the graduate registry.

The ledger was organized by year with each entry containing a graduate’s name, age, parent, or guardians name, and a brief note about their subsequent activities.

Deacon Morris pulled up two folding chairs, and they sat together examining the remarkable document.

The first entry was dated June 1883.

Rebecca Thompson, age 17, daughter of James Thompson, minister, completed four-year course of study, currently teaching at our Sunday school.

15 names followed for that year alone, each representing a young black woman who had risked everything to obtain an education that society told her she didn’t deserve.

Lauren turned through the pages year by year, watching the registry grow.

By 1890, the Evening Academy was graduating 20 to 25 students annually.

The notes revealed an emerging network.

graduates became teachers themselves, tutoring younger students, establishing small private schools in their homes, working as governnesses for sympathetic white families where they could quietly educate the children beyond what official schools provided.

She reached August 1895 and found the entries she was looking for.

Sarah Williams, age 16, daughter of Benjamin Williams, printer, completed four-year course.

Exceptional student in mathematics and literature will teach at Bethl.

And directly below, Kathern Henderson, age 16, daughter of Thomas Henderson, railroad clerk, completed four-year course alongside Sarah Williams, first white student of the evening academy, committed to continuing integrated education work.

Deacon Morris leaned closer to read the entry.

First white student, he repeated softly.

I never knew.

All these years, I assumed the Evening Academy served only black students.

Lauren turned to him.

Catherine’s mother worked at the day school.

Somehow she learned about the evening academy and convinced Eliza Foster to accept her daughter.

It must have been incredibly complicated and dangerous for everyone involved.

She continued reading.

The entry for Catherine included additional notes given special medallion and coding safe locations for integrated study.

We’ll work independently but in coordination with evening academy graduates.

Communication to be maintained through coded correspondence.

The medallions suddenly made complete sense.

They weren’t just graduation gifts or symbols of achievement.

They were practical tools, encoding the addresses of safe locations where integrated education could continue, where graduates could meet, coordinate, and support each other’s work.

The coordinates engraved on each medallion were different.

Lauren checked several of the ones in the crate and confirmed that each pointed to a different location around Atlanta.

“These were meeting places,” she said to Deacon Morris.

“A whole network of them spread across the city.

The graduates could recognize each other by the medallions and know they were safe to speak freely, to coordinate their teaching efforts.

” Deacon Morris nodded slowly.

Secret in plain sight, just like this church.

We held services on Sundays, looking like any other black church.

But during the week, we were running schools, holding meetings, planning strategies.

The white authorities suspected, but they could never prove anything.

Lauren turned to the final pages of the registry.

The last entry was dated May 1897.

Final graduation held in private ceremony.

16 students completed course.

Evening academy closing due to increased surveillance and threats.

graduates equipped with medallions and instructed in continued coordination.

Network continues.

Below that, in different handwriting, perhaps added years later, someone had written, “The evening academy ended, but its work did not.

The graduates taught for decades, educating hundreds.

Some lived to see integration.

All kept the faith.

” Deacon Morris led Lauren to the church office where he unlocked a filing cabinet containing archived correspondents from the early 1900s.

And when we digitized our historical records a few years ago, we set aside letters that seemed to be in code.

We couldn’t make sense of them, but they seemed important, so we preserved them.

He pulled out a folder containing dozens of letters, all dated between 1895 and 1920.

Lauren spread them across the desk and immediately recognized the pattern Eliza Foster had described in her journal, Book Ciphers.

Each letter referenced specific books, chapters, and word positions.

Anyone intercepting the letters would see only ordinary correspondence about literature and scripture.

But to those who knew the system, each letter contained detailed information.

Lauren photographed several letters and spent the evening at home decoding them using common books from the era.

The King James Bible, Shakespeare’s collected works, and the complete works of Alfred Lord Tennyson, which she found referenced repeatedly.

The first letter she successfully decoded was dated September 1895 from Sarah to Catherine.

Meeting successful.

Seven new students enrolled.

Location secure.

Your assistance with mathematics curriculum welcomed.

Book distribution arranged through usual channels.

Coordinates remain valid.

Hope sustained.

The letters revealed an extraordinary operation.

After the evening academy officially closed, its graduates continued the work independently, running small schools and homes, churches, and businesses throughout Atlanta.

Katherine taught white students during the day in her capacity as a private tutor.

But she also secretly taught black students in the evenings using the network’s safe locations.

Sarah coordinated the efforts from Bethlehem, matching students with teachers, distributing books and materials, and maintaining communication across the network.

One letter from 1898 showed the dangers they faced.

Incident last week, suspected but not confirmed.

Moved operations to alternate location per medallion coordinates.

All students safe.

Increased caution necessary.

Will reduce visible communication.

Trust in the pattern.

The pattern, the medallion system, had allowed them to adapt quickly when threatened, moving operations to pre-established safe locations without need for direct, risky communication.

It was brilliant in its simplicity and effectiveness.

Lauren found letters spanning more than two decades, the handwriting changing as the writers aged, the tone evolving from youthful determination to mature wisdom.

A letter from 1910 mentioned, “17 teachers now working independently, coordinating through our system.

Estimated 300 students educated in the past year alone.

By 1915, the letters referenced changing times.

The world shifts slowly toward justice.

Our work continues, but with less danger now.

Young people today cannot imagine what we faced in our youth.

Yet the struggle remains unfinished.

The final letter in the collection was dated 1920, written in shaky handwriting that Lauren recognized from comparing it to earlier letters as Catherine’s.

Dearest Sarah, 40 years since we met in Eliza’s classroom.

Our medallions, worn smooth by time and touch, still guide us.

How many have we taught? How many lives changed? We cannot know the full measure, but we know it matters.

The Evening Academy may be history, but its light still illuminates.

With eternal friendship and shared purpose, Catherine Lauren spent the next 3 weeks tracking down descendants of the Evening Academy graduates.

Using the registry as a starting point, she searched genealological databases, reached out to local family history societies, and posted inquiries in community forums.

The responses came slowly at first, then in a flood as word spread about her research.

She organized a gathering at at the Georgia Historical Archive on a Saturday morning in October.

43 people attended, representing 17 different families connected to the evening academy.

They ranged in age from elderly grandchildren of graduates to young adults who had only recently learned about their ancestors involvement in the secret school.

Lauren had prepared a presentation, but she began by simply showing the photograph of Catherine and Sarah, projected large on the screen at the front of the room.

The image of the two young women holding hands, clutching their medallions, filled the space with silent power.

This photograph was taken 129 years ago.

Lauren said, “These two 16-year-old girls risked everything to learn together to maintain a friendship that their society deemed illegal and immoral.

They weren’t content to just save themselves.

They spent their lives educating others, building a network that operated in secret for decades.

She clicked to the next slide, showing the medallion detail.

Each graduate received one of these.

They were encoded with coordinates to safe locations, symbols of a network that helped hundreds of young black women and at least one white woman receive educations they were denied by law.

One attendee, a woman in her 70s named Grace Thompson, raised her hand.

My grandmother was Rebecca Thompson, one of the first graduates in 1883.

I have her medallion.

My mother gave it to me before she died, but she never explained what it meant.

She just said to keep it safe, that it was important.

Others began speaking up.

Five people had brought medallions passed down through their families.

Each one identical to those Lauren had found at the church.

Each one preserved as a cherished heirloom, even when its meaning had been lost to time.

Lauren spent the next hour sharing what she had discovered.

The journal entries, the letters, the registry, the network’s scope and longevity.

She showed documents that proved how the graduates had continued teaching for decades, adapting their methods as times changed, persisting through danger and discrimination.

An elderly man named James Williams stood up, his voice shaking with emotion.

Sarah Williams was my great great grandmother.

I knew she was a teacher, but I never knew the story.

I never knew she was this brave, this committed.

He pulled a small wooden box from his bag and opened it.

Inside was Sarah’s medallion, polished and preserved, alongside a photograph Lauren had never seen.

Sarah and Catherine in their 60s standing together in front of Bethl amme church, their arms around each other’s shoulders, both smiling broadly.

This photo was taken in 1939.

James said, “My grandmother told me these two women were best friends their entire lives, but she said I wouldn’t understand why that was significant.

Now I do.

” Lauren felt tears streaming down her face as she looked at the image of the two elderly friends, separated by race in the eyes of their society, but united by decades of shared purpose and love.

Three months later, the Georgia Historical Archive opened its new permanent exhibition.

The Evening Academy, Secret Education, and Quiet Revolution in Jim Crow, Atlanta.

The centerpiece was the original photograph of Catherine and Sarah, professionally restored and enlarged, mounted alongside a display case containing 12 medallions, the graduate registry, and carefully curated selections from Eliza Foster’s journal and the coded correspondents.

Lawrence stood near the entrance on opening day, watching visitors move through the exhibition.

The response had been overwhelming.

Local news coverage had brought national attention to the story and people traveled from across the country to see the exhibition and learn about their own ancestors connections to the network.

The exhibition told the story chronologically, beginning with the founding of the evening academy in 1882 and following its evolution into a broader network that persisted into the 1920s.

Interactive displays allowed visitors to decode sample letters using the book’s cipher system, to explore maps showing the locations encoded in various medallions, and to read testimonials from graduates about their experiences.

One wall was dedicated to the long-term impact of the network.

Researchers had documented hundreds of students educated through the evening academy and the subsequent network.

Many had become teachers themselves, establishing schools throughout Georgia and beyond.

Some of their descendants had become leaders in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, carrying forward the commitment to education and equality that had been instilled generations earlier.

Katherine and Sarah’s story formed the emotional heart of the exhibition.

The original photograph was displayed alongside the 1939 image James Williams had shared, showing their lifelong friendship.

The letters between them, decoded and translated, revealed not just coordination of educational efforts, but also deep affection, mutual support through decades of challenges, and unwavering commitment to their shared vision.

Lauren watched as Grace Thompson, Rebecca’s granddaughter, stood before the display case containing her grandmother’s medallion, which she had donated to the exhibition.

Grace’s teenage granddaughter, stood beside her, reading the explanatory text aloud.

“So, great great grandma Rebecca went to this secret school?” the teenager asked.

Grace nodded, her voice filled with pride.

She did.

And then she spent her life teaching others, passing on what she learned.

Every education you and I have received, everything we’ve been able to accomplish, it started with her courage.

Near the exhibition’s exit, Lauren had created a reflection space where visitors could leave their thoughts.

A quote from Eliza Foster’s journal was painted on the wall.

Knowledge illuminates.

It cannot be contained by unjust laws or dimmed by hatred.

Once lit, it passes from person to person, generation to generation, an eternal flame of human dignity.

As the afternoon sun streamed through the archives windows, Lauren observed an elderly white woman and an elderly black woman standing together before the photograph of Catherine and Sarah.

They were holding hands, their heads close together as they read the accompanying text, and Lauren realized they were mirroring the pose of the two young women in the 1895 photograph.

The woman turned and saw Lauren watching.

“My grandmother knew Katherine Henderson,” she said.

She told me stories about a teacher who believed all children deserved education regardless of color.

I never understood the full significance until today.

The other woman nodded.

And my grandmother was taught by Sarah Williams at Bethlehem.

She said, “Miss Sarah taught her to read when she was 8 years old, and that gift changed her entire life.

” The two women looked at each other, then back at the photograph, understanding flowing between them across the decades.

Lauren smiled, thinking about the medallions and their Latin inscription.

Santia illuminate.

knowledge illuminates.

Katherine and Sarah had understood that truth at 16 years old, and they had spent their lives proving it.

The photograph that had seemed like merely a curious historical artifact had revealed itself to be evidence of something profound.

Ordinary people doing extraordinary things, fighting injustice with patience and courage, building networks of hope that outlasted the hatred array against them.

The Evening Academy had ended more than a century ago, but its light still illuminated, revealing truths about courage, friendship, and the unstoppable power of education to transform lives and challenge injustice.

Two young women holding hands and clutching their medallions had sparked a quiet revolution.

News

🚛 HIGHWAY CHAOS — TRUCKERS’ REVOLT PARALYZES EVERY LAND ROUTE, KHAMENEI SCRAMBLES TO CONTAIN THE FURY 🌪️ The narrator’s voice drops to a biting whisper as convoys snake through empty highways, fuel depots go silent, and leaders in Tehran realize this isn’t just a protest — it’s a nationwide blockade that could topple power and ignite panic across the region 👇

The Reckoning of the Highways: A Nation on the Edge In the heart of Tehran, the air was thick with…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Darkened City: A Night of Reckoning In the heart of Moscow, a city that once stood proud and unyielding,…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Shocking Resurrection: A Hollywood Revelation In a world where faith intertwines with fame, the announcement sent ripples through the…

🎬 “TO THIS DAY, NO ONE CAN EXPLAIN IT” — JIM CAVIEZEL BREAKS YEARS OF SILENCE ABOUT THE MYSTERY THAT HAUNTED HIM AFTER FILMING ⚡ In a hushed, almost trembling confession, the actor leans back and stares past the lights, hinting at strange accidents, eerie coincidences, and moments on set that felt less like cinema and more like something watching from the shadows, leaving even hardened crew members shaken to their core 👇

The Unseen Shadows: Jim Caviezel’s Revelation In the dim light of a secluded room, Jim Caviezel sat across from the…

📜 SEALED FOR CENTURIES — ETHIOPIAN MONKS FINALLY RELEASE A TRANSLATED RESURRECTION PASSAGE, AND SCHOLARS SAY “NOTHING WILL BE THE SAME” ⛪ The narrator’s voice drops to a breathless whisper as ancient parchment cracks open under candlelight, hooded figures guard the doors, and words once locked inside stone monasteries spill out, threatening to shake faith, history, and everything believers thought they understood 👇

The Unveiling of Truth: A Resurrection of Belief In the heart of Ethiopia, where the ancient echoes of faith intertwine…

🕯️ FINAL CONFESSION — BEFORE HE DIES, MEL GIBSON CLAIMS TO REVEAL JESUS’ “MISSING WORDS,” AND BELIEVERS ARE STUNNED INTO SILENCE 📜 The narrator’s voice drops to a hushed, dramatic whisper as old notebooks open, candlelight flickers across ancient pages, and Gibson hints that lines never recorded in scripture could rewrite everything the faithful thought they knew 👇

The Unveiling of Hidden Truths In the dim light of his private study, Mel Gibson sat surrounded by piles of…

End of content

No more pages to load