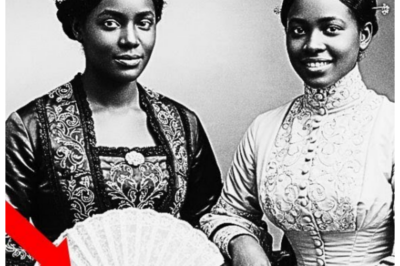

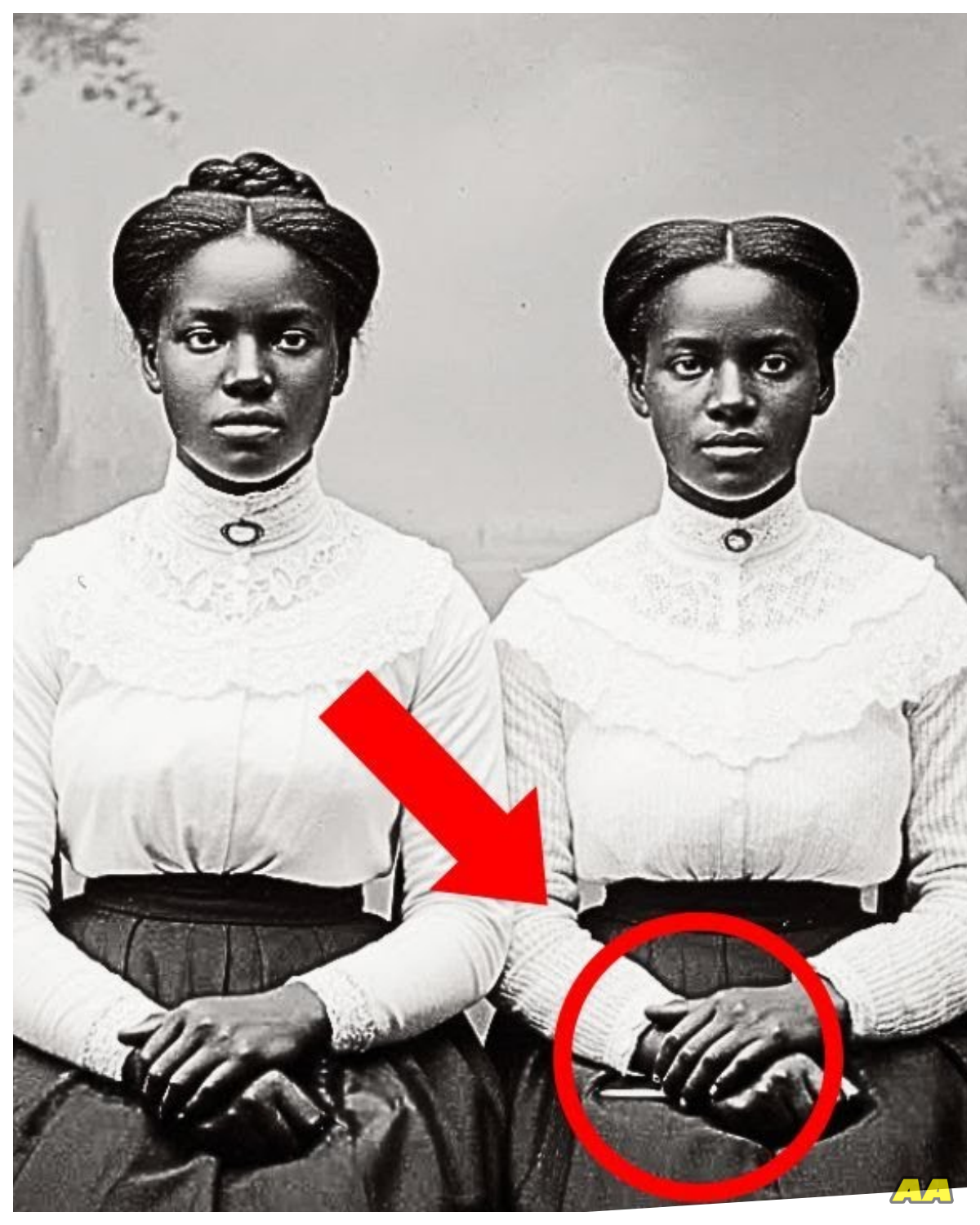

This 1899 photo of two sisters looks peaceful until you notice what one of them is holding.

Why would a simple studio portrait of two young women shock historians and force them to rewrite what they thought they knew about the end of slavery in America? Dr.

Marcus Chen stood in the climate controlled archive room of the Library of Congress in Washington DC on a cold January morning in 2021, staring at a photograph that would haunt him for months to come.

The image had arrived as part of a large donation from a private collector’s estate.

hundreds of 19th century photographs, most of them typical studio portraits of families, couples, and individuals from across the American South.

This particular photograph dated 1899 on the photographers’s mount showed two young black women seated side by side in an elegant studio setting.

A painted backdrop depicted a garden scene with classical columns.

The women wore identical high- necked white blouses with delicate lace collars and long dark skirts.

Their hair was styled in the Gibson girl fashion popular at the turn of the century, swept up in soft pompadors.

Both women had the same distinctive features, high cheekbones, expressive eyes, and a subtle resemblance that suggested they were sisters.

The photograph appeared unremarkable at first glance.

Studio portraits like this were common in the late 1890s when photography had become affordable enough that middle-class families could afford professional sittings.

The women looked prosperous, dignified, and calm.

Everything about the image suggested success and stability, but something about their expressions made Marcus pause.

The woman on the left, who appeared to be the elder of the two, perhaps 20 years old, met the camera’s gaze directly with a look that seemed almost defiant.

Her posture was rigid, her shoulders squared as if she were preparing for battle rather than sitting for a portrait.

The younger woman, probably 18, sat with her hands folded in her lap, her face turned slightly toward her sister.

There was tension in the set of her jaw, a tightness around her eyes that didn’t match the peaceful studio setting.

Marcus had spent 15 years studying post civil war photography, learning to read the subtle details that revealed the truth behind posed images.

He had examined thousands of portraits from this era, learning to distinguish between the normal stiffness required by long exposure times and the kind of tension that suggested deeper emotional undercurrents.

Something about this photograph felt profoundly wrong, though he couldn’t yet articulate what bothered him.

The women’s body language suggested they were braced for something, holding themselves with a kind of vigilant stillness that went beyond the normal requirements of 19th century portrait photography.

Their eyes, even in the faded sepia tones, held a watchfulness that seemed out of place in a formal studio setting.

This wasn’t the relaxed dignity of people celebrating an achievement or marking a special occasion.

This was the alertness of people who lived in constant awareness of danger.

Marcus carefully turned over the photograph’s mounting board.

The photographers’s stamp read, “Hartwell Portrait Studio, Lexington, Kentucky, Estains, 1887.

” A handwritten notation in faded ink said simply, “The sisters, October 1899.

” No names, no other context, no explanation of who these women were or why their portrait had been taken.

He logged the image into the archive system and flagged it for high resolution scanning.

The Library of Congress had recently acquired scanning equipment capable of capturing extraordinary detail.

Technology that could reveal elements invisible to the naked eye.

Details that the original photographer might not even have noticed.

Marcus had learned over the years that the most important historical discoveries often hid in plain sight, waiting for someone with the right tools and the right questions to look closely enough to see what was really there.

He had no idea that this routine cataloging decision would lead him to one of the most disturbing discoveries of his career.

Three weeks later, Marcus received notification that the highresolution scan was complete.

He had thought about the photograph of the two sisters several times in the intervening weeks.

That sense of unease returning whenever the image crossed his mind, but the demands of other projects had prevented him from dwelling on it.

Now settling at his computer with his morning coffee, he opened the digital file and felt that inexplicable disqu flood back immediately.

He began his examination systematically, as he always did, zooming in on different sections of the image to note details for the permanent record.

The studio backdrop was typical of the era, mass-produced painted canvas depicting an idealized garden setting with Greco Roman architectural elements that suggested refinement and classical beauty.

The women’s clothing, though simple in style, showed evidence of quality fabric and skilled tailoring.

The white blouses were starched and pressed, the lace collars handmade.

Their jewelry was minimal but meaningful.

The elder sister wore a small silver cross on a thin chain, while the younger had a simple band on her right hand.

Marcus zoomed in on their faces, studying the subtle details of their expressions.

The elder sister’s direct gaze into the camera lens was unusual for the era, when women were typically photographed with downcast or averted eyes to suggest modesty and propriety.

This woman looked straight ahead with an intensity that seemed to challenge the viewer.

Her lips were pressed together in a thin line, and there was something in the set of her eyebrows that suggested both determination and barely contained anger.

The younger sister’s expression was different, but equally unsettling.

Her eyes were cast slightly downward, but not immodesty.

There was a weariness in her face, a careful blankness that seemed designed to conceal rather than reveal emotion.

It was the expression of someone who had learned to hide what they were feeling to present an acceptable facade while guarding their true thoughts.

Then Marcus zoomed in on the younger sister’s lap, where her hands were folded demely over her dark skirt, and his breath stopped.

At 50 times magnification, what had appeared to be shadows in the fabric and the natural draping of the young woman’s hands revealed itself to be something else entirely.

The younger woman’s right hand was positioned carefully over her left and between her fingers, barely visible against the dark material of her skirt, was the edge of something that caught the light.

Marcus adjusted the contrast and brightness, his heart beginning to pound as the object became clearer.

It was a blade, a small dagger, or knife no more than 4 in long, with what appeared to be a bone or ivory handle.

The younger sister was gripping it between her fingers, holding it flat against her thigh, where it would be invisible to casual observation, but ready to be drawn at a moment’s notice.

Marcus sat back from his monitor, his hands trembling.

This was no decorative accessory, no innocent element of costume.

This was a weapon deliberately concealed, carried with obvious practice and familiarity, and it had been brought into a photographer’s studio and documented in a formal portrait.

The question that had started his investigation, why would this photograph shock historians, suddenly had a partial answer, but that answer only raised more urgent and disturbing questions.

Why did these young women need a hidden weapon? What were they protecting themselves from? And what did this reveal about their lives in Kentucky in 1899, 34 years after slavery had supposedly ended? Marcus knew that understanding what he had found required identifying the two sisters and learning their stories.

He began with the photographers’s studio, Hartwell Portrait Studio in Lexington, Kentucky had operated from 1887 until 1903.

According to business directory records Marcus found in the Kentucky Historical Society’s archives, the studio had been owned by a man named Edmund Hartwell, a white photographer who had advertised his services to all respectable citizens regardless of station.

That phrase, regardless of station, was significant.

In 1899, Kentucky, most photography studios served exclusively white clientele or maintained separate facilities for black customers.

A studio that openly advertised its willingness to photograph black clients was unusual enough to be noteworthy, and it suggested that Hartwell might have kept records of his black customers that other studios would have ignored or discarded.

Marcus contacted the Lexington Public Library special collections department, explaining what he was looking for.

A librarian named Janet Foster responded with unexpected news.

The library held a collection of Edund Hartwell’s business records, including appointment books and some customer receipts donated by Hartwell’s granddaughter in the 1970s.

Two weeks later, Marcus was in Lexington, sitting in the library’s reading room with three leatherbound appointment books spread before him.

The entries for October 1899 showed a steady stream of customers, families, individuals, couples preparing for weddings.

On October 14th, 1899, an entry read, 10:30 a.

m.

, portrait sitting, two subjects, special arrangement, payment received in advance.

The cryptic notation, special arrangement, appeared only a handful of times in the appointment books, Marcus examined.

Most entries simply listed the customer’s name, the type of portrait requested.

But this entry and a few others scattered through the years used this particular phrase.

Marcus wondered what it meant.

A discount for struggling customers, a favor for someone Hartwell knew personally or something else entirely.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected source.

Janet Foster mentioned that the library also held records from the Lexington Colored Orphan Asylum, an institution that had operated from 1892 to 1915, providing care for black children whose parents had died or could no longer care for them.

Among the asylum’s records was a visitors log documenting people who came to inquire about children, make donations, or in rare cases, reclaim children who had been placed there temporarily.

In the visitors log for October 1899, Marcus found an entry that made his pulse quicken.

October 15th, 1899.

Hannah and Grace, ages 20 and 18, inquired about younger brother Thomas, age 8, placed in asylum care.

June 1899, informed that Thomas had been transferred to apprenticeship arrangement.

Sisters visibly distressed, provided no further information for policy.

Hannah and Grace, two sisters the right ages, visiting the day after that mysterious portrait sitting.

Marcus felt certain he had found them, but the entry raised as many questions as it answered.

Why had their younger brother been placed in an orphanage? What was this apprenticeship arrangement he had been transferred to? And why had the sisters been denied information about their own brother? Marcus spent the next week digging through more records, trying to piece together the sister’s story.

To understand what had happened to Thomas and why his sisters had been searching for him, Marcus needed to learn about Kucky’s apprenticeship system in the 1890s.

He contacted Dr.

Angela Roberts, a historian at the University of Kentucky, who had published extensively on post civil war labor practices in the state.

When Marcus explained what he had found, Angela’s response was immediate.

You need to come see my research.

What you’re describing sounds like evidence of one of the darkest chapters in Kucky’s history.

3 days later, Marcus sat in Angela’s office surrounded by file boxes containing records she had spent years collecting from county courouses across Kentucky.

After the Civil War, Angel explained, southern states found ways to maintain control over black labor despite the 13th Amendment’s prohibition of slavery.

One of the most insidious methods was the apprenticeship system.

She pulled out a stack of legal documents.

Kentucky law allowed courts to declare black children orphans, even if their parents were alive, and then apprentice those children to white families or businesses until they reached adulthood.

The stated purpose was to provide care and training for destitute children.

The reality was forced labor that differed from slavery only in name.

Marcus examined the documents Angela spread before him.

Court orders declaring children orphans despite having living parents.

Apprenticeship contracts that bound children to work without wages until age 18 or 21.

Testimonies from adults who had been apprenticed as children.

Describing beatings, starvation, and working conditions identical to slavery.

The system targeted families in desperate circumstances.

Angela continued, “If a parent died, if a family fell into debt, if someone was arrested and couldn’t care for their children, the courts could seize the children and apprentice them.

And once a child was in the system, getting them back was nearly impossible.

The law heavily favored the masters who held the apprenticeship contracts.

She pulled out a map of Kentucky with certain areas marked in red.

Lexington and the surrounding bluegrass region had particularly aggressive enforcement of apprenticeship laws.

Between 1865 and 1900, thousands of black children were apprenticed.

many of them to the same plantation owners who had enslaved their parents before the war.

Marcus shared what he had found in the asylum records, the notation about Thomas being transferred to an apprenticeship arrangement.

Angela nodded grimly.

The orphan asylum was often used as a holding facility.

Children would be placed there temporarily, then transferred to whoever had requested an apprentice.

The families were rarely told where their children were being sent or given any way to contact them.

Angela pulled out one more document, a list of apprenticeship contracts filed in Fet County, which included Lexington between 1898 and 1900.

Marcus scanned through the names and there it was.

Thomas, negro male child, approximately 8 years of age, apprenticed to Samuel Blackwood, Tobacco Plantation, Scott County.

Term until age 21, filed June 1899.

Thomas had been sent to a tobacco plantation 30 m from Lexington.

His sisters Hannah and Grace would have had almost no legal recourse to get him back.

The apprenticeship contract gave Samuel Blackwood complete control over Thomas until he reached 21.

13 more years of unpaid labor of childhood stolen, a family separated by a system designed to exploit black children under the thin veneer of legal process.

Marcus stared at the document, understanding now the desperation that must have driven Hannah and Grace.

They had lost their brother to a system that was slavery in everything but name, and they had been powerless to stop it.

Understanding why Hannah and Grace had posed for that photograph and why Grace had been carrying a concealed weapon required Marcus to learn more about their own circumstances in Lexington in 1899.

He returned to the census records and city directories.

This time armed with their names and approximate ages.

The 1900 census taken just months after the photograph was made listed Hannah and Grace as servants living in the household of a family named Preston on West Main Street in Lexington.

The Preston household consisted of Robert Preston, a tobacco merchant.

his wife Elizabeth and their three children.

Hannah was listed as a cook, Grace as a housemmaid.

The census noted that neither young woman could read or write, and both were listed as single.

But Marcus found something disturbing in the employment records Angela had collected.

A notation in the Fet County Court records from July 1899, just one month after Thomas had been apprenticed, showed that Hannah and Grace had been bound to the Preston household through what was called an indenture agreement.

Like their brother’s apprenticeship, this was a legal contract that required them to work for the Preston family without wages, supposedly in exchange for room, board, and training and domestic service.

The key difference was that Hannah and Grace were adults, not children.

Yet, they had been forced into a contract that bound them to unpaid labor for a period of 5 years.

How had this happened? Angela helped Marcus search through court records for the answer.

They found it in a debt case filed in June 1899.

According to the court documents, Hannah and Grace’s father had died in May 1899, leaving debts to a local merchant who had extended credit for food and supplies.

The merchant had demanded immediate payment from the daughters.

When they couldn’t pay, the merchant had taken them to court.

The judge had ruled that the young women owed $60, a sum they had no way to obtain, and had given them a choice, jail or indenture.

They had chosen indenture, signing contracts that bound them to 5 years of domestic service to pay off their father’s debt.

The Preston family had paid the merchant directly and taken possession of Hannah and Grace’s labor.

It was debt punage, another system that trapped black Americans in conditions barely distinguishable from slavery, using legal mechanisms to enforce bondage that the 13th amendment had supposedly abolished.

Marcus found testimony from other women who had been similarly trapped.

In interviews conducted in the 1930s as part of a depression era documentation project, elderly women described the reality of domestic service under indenture.

Working from before dawn until late at night, sleeping in unheated attic rooms, eating scraps from the family’s table, subjected to physical punishment for any perceived disobedience and living under constant threat of violence.

And they described something else that made Marcus understand why Grace had carried a weapon into the photographers’s studio.

Multiple testimonies mentioned that young women in domestic service faced constant danger of sexual assault from the men in the households where they worked.

With no legal protection, no ability to leave their employment, and no recourse if they were attacked, these women lived in a state of perpetual vulnerability.

Grace’s hidden dagger was not a dramatic gesture.

It was a desperate necessity, a tool of last resort for a young woman who understood that the law would not protect her and that her only defense was whatever protection she could provide for herself.

Marcus needed to understand Edmund Hartwell’s role in this story.

Why had the photographer agreed to take the portrait? What was the special arrangement noted in his appointment book? And did Hartwell understand what Grace was carrying when he posed the two sisters for their photograph? The answer came from an unexpected source.

Marcus received an email from a woman named Katherine Hartwell Morrison who had seen his inquiry on a genealogy forum where he had posted information about Edund Hartwell.

Katherine was Edund’s great great granddaughter and she had boxes of family papers that had never been donated to any archive.

When Marcus visited Catherine in Louisville, she brought out a collection of letters and personal journals that Edmund had kept.

My family has always known that Edmund was sympathetic to the black community.

Katherine explained, “He was a Quaker and he believed strongly in equality and justice, but he had to be careful about how he expressed those beliefs in Kentucky in the 1890s.

” Edmond’s journal entries from October 1899 told the story.

On October 13th, he had written, “Visited today by two young women of color, sisters named Hannah and Grace.

They came not to request a portrait for vanity, but to document something important.

They would not explain in detail, but I understood that they wished to create a record of themselves, to prove their existence and their resistance to circumstances they could not fully escape.

I agreed to photograph them tomorrow, and to ask no questions that might put them in danger.

” The next day’s entry was more detailed, made the portrait of the sisters today.

They arrived precisely at the appointed time, dressed in their finest clothes, which they said belonged to the household where they worked.

The younger one, Grace, carried something concealed in her clothing.

I saw the glint of metal when she arranged her skirt.

I chose not to mention it, understanding that whatever she carried was for her protection in a world that offers women like her little safety.

Edmund had positioned them carefully, he wrote, to ensure that the concealed weapon would be captured by the camera, but would not be obvious to casual observation.

If they wish to document their circumstances, including their need to protect themselves, then I will help them do so.

A photograph is evidence, and evidence may someday serve justice, even when the present offers none.

” The entry continued, “They paid me with coins they said they had saved secretly over many months.

Money earned through small services they provided outside their required labor.

They asked me to make two copies of the photograph, one for them to keep, and one to be sent to an address in Philadelphia, to a Quaker organization that documents injustices in the South.

I will honor this request.

Marcus felt a chill reading these words.

The photograph had been created deliberately as documentation, as evidence of the sister’s situation, and it had been sent to an organization that collected such evidence, though clearly the evidence had not been enough to change their circumstances or rescue their brother.

Catherine showed Marcus one more item, a small envelope containing a lock of hair and a note in Edmund Hartwell’s handwriting, dated November 1899.

The elder sister, Hannah, returned today to tell me her sister Grace was killed.

She did not provide details, but her grief and rage were apparent.

She asked me to keep this lock of Grace’s hair and to remember that her sister had been a person of dignity and courage.

I will remember.

Marcus knew he needed to find out what had happened to Grace in the month after the photograph was taken.

He returned to the Fet County Court records, searching for any mention of her name in October or November 1899.

What he found was a brief newspaper article from the Lexington Daily Press dated November 3rd, 1899, buried in the back pages among minor local news items.

Unfortunate incident on West Main Street.

A negro servant girl employed in the household of Mr.

Robert Preston, suffered fatal injuries on the evening of November 2nd.

According to reports, the girl identified as Grace, approximately 18 years of age, fell from a second story window while performing her duties.

A physician was summoned, but the injuries proved fatal.

The coroner has ruled the death accidental.

The girl’s remains were claimed by her sister and buried in the colored section of Lexington Cemetery.

Marcus read the article three times, his hands shaking, fell from a second story window while performing her duties.

The passive construction, the vague circumstances, the quick ruling of accident, everything about the brief report screamed of a coverup.

What had really happened on that November evening? He searched for more information and found a coroner’s report in the court archives.

The document was prefuncter.

Female negro approximately 18 years, deceased from injuries consistent with fall from height, multiple contusions, and broken bones.

No witnesses to the fall.

Death ruled accidental.

But Marcus also found something else.

A complaint filed with the Lexington Police Department 3 days after Grace’s death.

The complaint had been filed by Hannah, and though it had been dismissed almost immediately, the record of it remained.

Hannah had claimed that her sister had been attacked by Robert Preston, that Grace had fought back using a small knife she carried for protection, and that Preston had thrown her from the window in rage.

Hannah had demanded an investigation and prosecution.

The police response, noted at the bottom of the complaint, was brief.

Complainant is a negro servant with questionable moral character.

Accused is a respectable businessman and family man.

No credible evidence supports the allegation.

Complaint dismissed.

Marcus sat in the archive reading room staring at these documents, understanding the full horror of what had happened.

Grace had carried that weapon in the photograph because she knew she was in danger.

She had documented herself holding it, creating evidence of her need for protection.

And when she had used it to defend herself from assault, she had been murdered for her resistance.

The system had then protected her killer, dismissing her sister’s testimony, ruling the death accidental, and ensuring that no justice would ever be served.

Angela Roberts helped Marcus search for more information about Robert Preston.

They found that he had continued his tobacco business for years after Grace’s death, had served on the Lexington City Council, and had died in 1918 prosperous and respected.

His obituary made no mention of any scandal or controversy.

The system had protected him completely.

They also found records showing that Hannah had been forced to complete her 5-year indenture contract despite her sister’s death, working in the Preston household until 1904.

The psychological torture of being forced to serve the man who had killed her sister was almost incomprehensible.

Marcus understood now why this photograph was so important, why it had to be examined, documented, and shared.

It was one of the only pieces of evidence that Grace had existed, that she had been a person with dignity and agency, that she had tried to protect herself in a world determined to render her powerless.

After completing her indenture in 1904, Hannah had disappeared from Lexington’s records.

Marcus spent weeks trying to trace what had happened to her.

Searching through city directories and census records in Kentucky and surrounding states.

The trail seemed to have gone cold, a common problem when researching black women from this era, whose lives were often poorly documented.

The breakthrough came from the Quaker organization that Edmund Hartwell had mentioned in his journal.

Marcus contacted the American Friends Service Committee in Philadelphia and explained what he was researching.

An archist there searched through their historical records and found a file labeled Kentucky cases 1899 1905.

A inside was correspondence about Hannah and Grace, including letters from Edmund Hartwell describing their situation and his concerns about their safety.

But more importantly, there was a letter from Hannah herself dated January 1905 written in careful unpracticed handwriting that suggested she had recently learned to read and write.

Dear friends, the letter began.

My name is Hannah and I am writing to tell you that I have left Kentucky and come to Cincinnati where I am safe.

I worked 5 years for the man who killed my sister Grace.

Every day I thought about leaving, but I had no money and no place to go and I knew if I ran they would catch me and put me in jail or worse.

But I survived because I promised Grace I would live and tell the truth about what happened to her.

The letter continued, “I am working now in a factory making shirts.

The work is hard, but I am paid wages and I can leave when I choose.

I have joined a church here where there are other women who escaped from Kentucky and we help each other.

I wanted you to know that I am alive and free.

I also wanted to ask if you still have the photograph that Mr.

Hartwell sent you in 1899, the picture of me and Grace.

It is the only image of my sister that exists and I would like to have a copy of it if possible.

The file contained a response from the organization confirming they would send Hannah a copy of the photograph and offering her assistance in documenting her testimony about the apprenticeship system and her sister’s death.

There were several more letters from Hannah over the following years describing her life in Cincinnati, her work in various factories, and her involvement in church and community organizing.

In a letter from 1910, Hannah wrote about finding her brother.

After 6 years of searching, I have located Thomas.

He is still in Kentucky, still bound to that plantation until he turns 21.

I have written to him, though I do not know if my letters reach him.

I am saving money to help him when he is finally freed.

He will be 19 then, with no education, no family nearby, nothing but years of stolen childhood.

But I will be here for him, and together we will build a life that honors Grace’s memory.

Marcus found Thomas in the 1920 census, living in Cincinnati with his sister Hannah.

He was working as a laborer and Hannah was listed as a seamstress running her own small dress makingaking business from their home.

They had survived, had found each other again, and had built a life in freedom despite everything the system had tried to take from them.

Hannah lived until 1947, dying at the age of 68.

Her obituary in the Cincinnati Inquirer was brief, but mentioned that she had been active in civil rights organizing, had helped establish a home for working women, and had been known in her community as someone who helped young people who had escaped from difficult situations in the South.

By late 2021, Marcus had compiled his research into a comprehensive documentation of Hannah and Grace’s story.

He prepared an article for the Journal of African-American History and began working with the Library of Congress to create an exhibition featuring the photograph and the evidence he had gathered.

The photograph with Grace’s concealed weapon visible only under magnification became the centerpiece of an exhibition titled Hidden Defenses: Resistance and Survival in the Post Emancipation South.

The exhibition included the photograph itself, Edmund Hartwell’s journal entries, Hannah’s letters, court records documenting the apprenticeship system and Grace’s death, and testimony from other women who had survived similar circumstances.

News of the discovery spread quickly through academic and genealological networks.

Researchers began examining other photographs from the same era, looking for similar instances of concealed weapons or other forms of documentation hidden in plain sight.

Several more examples emerged.

Photographs of domestic workers with kitchen knives discreetly visible.

Images of field workers with tools that could serve as weapons, portraits of women with defensive postures that suggested constant vigilance.

The story resonated particularly strongly with descendants of people who had lived through the post-emancipation period.

Marcus received dozens of emails from people whose ancestors had been apprenticed, indentured, or trapped in debt penage.

Many shared family stories that had been passed down orally, but never documented.

Stories of resistance, survival, and the various ways people had tried to protect themselves and preserve evidence of the injustices they endured.

One email came from a woman named Joyce Miller in Cincinnati who said her grandmother had known Hannah personally.

My grandmother used to tell me about a woman in the neighborhood who had survived terrible things in Kentucky and who dedicated her life to helping other people escape similar situations.

She said this woman had lost a sister to violence and carried that grief her whole life but transformed it into action.

I believe she was talking about Hannah.

Joyce shared photographs from her grandmother’s collection, including one from the 1930s, showing a group of women from their church community.

In the center of the group, looking directly at the camera with the same fierce dignity Marcus had seen in the 1899 photograph, was an elderly woman Joyce identified as Hannah.

The exhibition traveled to museums in Cincinnati, Lexington, and Philadelphia.

Each venue adding local context about the systems that had trapped people like Hannah, Grace, and Thomas.

In Lexington, the exhibition sparked community conversations about confronting difficult history and led to efforts to research and memorialize others who had been victims of the apprenticeship system.

The University of Kentucky, where Angela Roberts taught, established a research initiative to document all known cases of apprenticeship and indenture in Kentucky between 1865 and 1920, creating a database that would preserve the names and stories of thousands of people whose experiences had been deliberately obscured or forgotten.

The photograph of Hannah and Grace with its hidden evidence of resistance and survival became one of the most significant historical documents in the Library of Congress’s collection of post civil war photography.

For Marcus, it represented everything he had dedicated his career to uncovering.

The hidden truths that revealed how people had fought against oppression with whatever tools they had, even when the systems arrayed against them seemed insurmountable.

In March 2022, the Library of Congress held a special program about the photograph and the history it revealed.

Descendants of Edund Hartwell, including Katherine Hartwell Morrison, attended and shared more family documents.

Descendants of Hannah and Thomas, located through genealogical research, also participated, bringing photographs and stories that had been preserved through generations.

Among them was Hannah’s great great niece, Dr.

Sandra Williams, a professor of African-American history at Howard University.

My family has always known pieces of this story, Sandra said during the program.

We knew that Hannah had escaped from Kentucky, that she had lost a sister to violence, that she had rescued her brother from forced labor.

But we never knew about the photograph, about the weapon Grace carried, about the deliberate documentation they created.

This discovery has given us concrete evidence of what our ancestors endured and how they resisted.

The weapon itself, Grace’s small dagger, had not survived, but its image, preserved in a photograph taken 123 years earlier, served as powerful testimony to the reality of young black women’s lives in 1899.

They had lived in constant danger, had been denied legal protection, had been trapped in systems that exploited their labor and exposed them to violence.

And they had armed themselves both literally and through the creation of evidence in whatever ways they could.

Marcus arranged for a memorial marker to be placed in Lexington Cemetery, where Grace had been buried in an unmarked grave in the colored section.

The marker, dedicated in June 2022, read, “Grace, approximately 1881 1899.

domestic worker, sister, and victim of violence.

She carried a weapon to protect herself in a world that offered her no protection.

She documented her resistance in a photograph that has become evidence of her courage and dignity.

Her life and death stand as testament to all who have fought for survival and justice against systems designed to destroy them.

The photograph remained on permanent display at the Library of Congress.

Grace’s steady gaze and carefully concealed weapon, a reminder of the hidden histories that survived in images, the truths that persisted despite efforts to erase them.

Every detail told a story.

The sisters identical white blouses likely borrowed from the household where they worked.

Their carefully styled hair assertion of dignity despite their circumstances.

Hannah’s defiant stare into the camera and Grace’s hands positioned so precisely to both hide and reveal the small blade that represented her only defense.

Marcus kept a copy of the photograph in his office.

Whenever he looked at it, he saw not just two young women from 1899, but all the people whose resistance had been hidden, whose courage had been documented in ways that seemed invisible until someone looked closely enough to see.

The question he had asked at the beginning, why would this photograph shock historians had been answered? It shocked because it revealed a truth that Americans had tried to forget.

that slavery’s end had not meant freedom’s beginning, that systems of oppression had continued under different names, and that people had fought back in whatever ways they could, creating evidence that would survive even when they did not.

Grace had lived only 18 years, but her image, with its hidden testimony to her circumstances and her resistance, would now be remembered and honored forever.

The truth she and Hannah had tried to preserve, had finally been seen, understood, and shared.

That was the power of a single photograph.

When someone finally looked closely enough to see what was hidden in plain sight.

News

📜 POPE LEO XIV UNSEALS A FORBIDDEN SCROLL FROM THE VATICAN VAULTS — CLAIMS IT REVEALS CHRIST’S “FINAL COMMANDMENT” HIDDEN FOR 2,000 YEARS, AND NOW CARDINALS ARE SCRAMBLING TO EXPLAIN THE SILENCE 🕯️ In a candlelit archive beneath St. Peter’s, the pontiff allegedly unveiled brittle parchment that insiders say could rewrite everything believers thought they knew, sparking whispers of cover-ups, shattered dogma, and a Church terrified of its own past 👇

The Revelation of the Hidden Scroll: A Journey into Darkness In the heart of the Vatican, a storm was brewing….

💥 15 NEW REFORMS SHAKE THE VATICAN — POPE LEO XIV DROPS A HOLY HAMMER ON CENTURIES OF TRADITION, CARDINALS STUNNED, DOORS SLAMMED, AND WHISPERS OF “SCHISM” ECHO THROUGH ST. PETER’S 🔔 In a move insiders call “the most explosive shake-up since the Middle Ages,” the new pontiff reportedly blindsided bishops at dawn with sweeping decrees that rewrite worship, power, and money itself, leaving the marble halls trembling and the faithful wondering who’s really in charge now 👇

The Awakening of Faith: A Shocking Revelation In a world where faith was a flickering candle, struggling against the winds…

It was just a photo of two sisters — but it hid a dark secret

It was just a photo of two sisters, but it hid a dark secret. The photograph appeared ordinary at first…

It Was Just a Portrait of a Mother and Her Children — But When Experts Zoomed In, They Paled

It was just a portrait of a mother and her children. But when experts zoomed in, they pald. Rebecca Turner…

It was just a photo of a girl with flowers — until you notice what she’s hiding in her hand

It was just a photo of a girl with flowers, but what she’s holding in her hand tells a different…

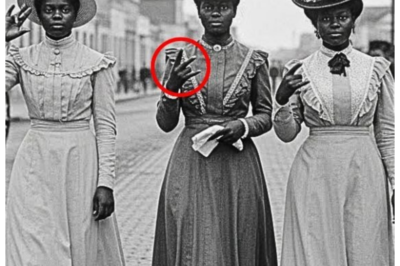

It was just a photo of three friends — until researchers deciphered the hand signal they were making

It was just a photo of three friends until researchers deciphered the hand signal they were making. The New Orleans…

End of content

No more pages to load