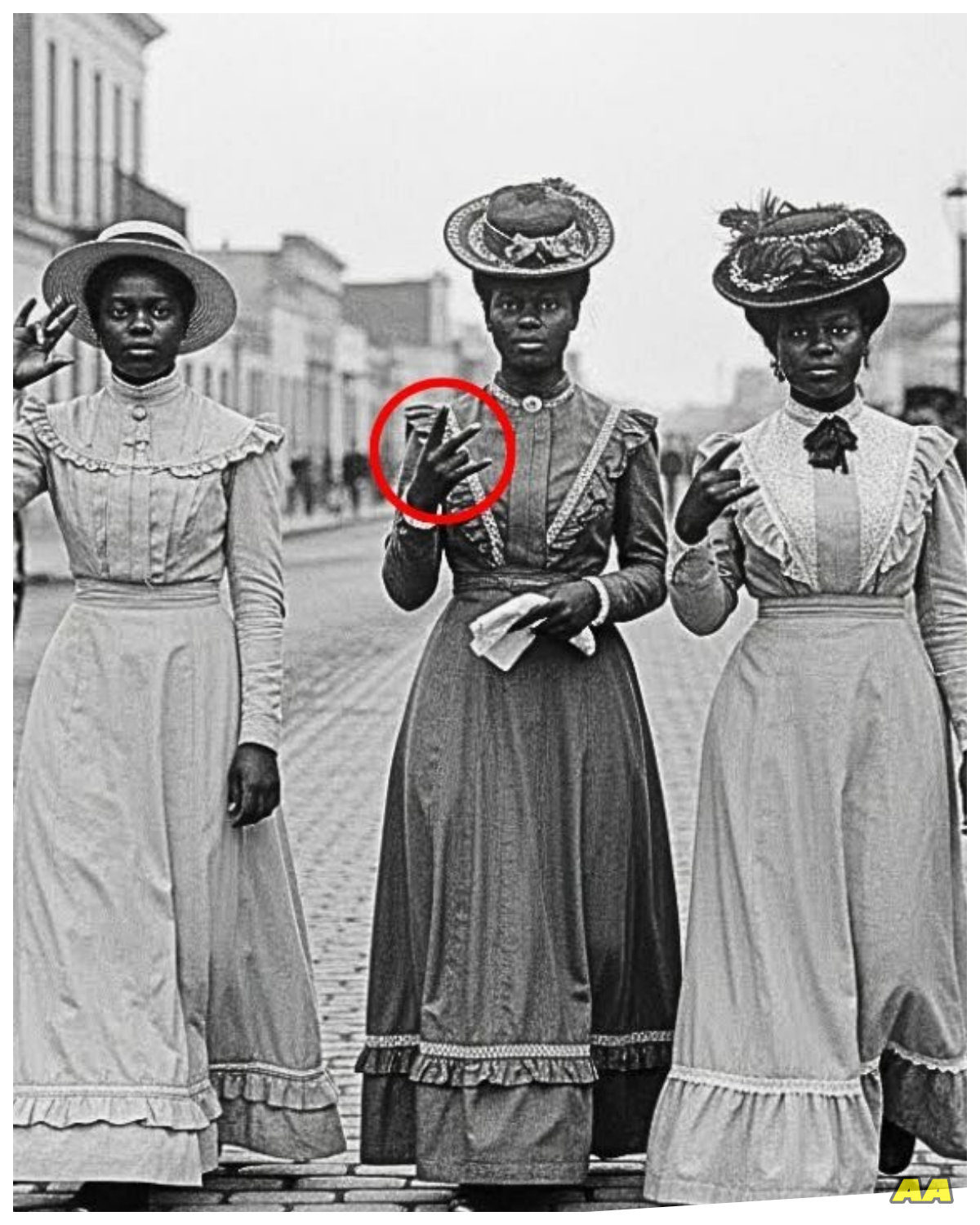

It was just a photo of three friends until researchers deciphered the hand signal they were making.

The New Orleans humidity hung heavy in the air as Dr.Sarah Bennett pushed open the door of Russo’s antique emporium on Royal Street.

It was late August 2024 and the oppressive heat seemed to seep through every crack in the French Quarters historic buildings.

Sarah had spent the past 3 years researching African-American women’s networks in the post reconstruction south, and she had learned that the best discoveries often came from the most unlikely places.

The shop was cluttered with the accumulated debris of forgotten lives, tarnished silverware, cracked porcelain dolls, oil paintings with peeling frames, and stacks upon stacks of old photographs.

The owner, an elderly Creole man named Maurice Rouso, barely looked up from his newspaper as Sarah entered.

Looking for anything particular? He asked without much interest.

“Phographs?” Sarah replied.

“Anything from the 1890s to early 1900s? Especially images with black subjects.

” Maurice gestured vaguely toward the back corner.

Got some boxes back there.

Estate sale from the Duvalier place.

Old French family.

Been here since before the Civil War.

Most of it’s junk, but you’re welcome to look.

Sarah made her way through the narrow ales.

Her trained eyes scanning the merchandise.

In the back corner, she found three cardboard boxes filled with photographs, letters, and documents.

She knelt down and began sorting through them carefully, her fingers moving with practiced delicacy through the fragile papers.

Most of the photographs were what she expected.

formal portraits of white families in Victorian dress, children posed stiffly in sailor suits, elderly couples celebrating golden anniversaries.

But near the bottom of the second box, wrapped in yellow tissue paper, she found something different.

The photograph was larger than most, approximately 10 x 12 in, and remarkably well preserved.

Unlike the formal studio portraits, this appeared to be a street photograph, capturing a moment of everyday life with unusual clarity for the era.

The image showed a bustling street scene in what Sarah immediately recognized as the French Quarter.

Buildings with characteristic row iron balconies lined both sides of the street, and numerous people moved through the frame, some blurred by motion, others captured with striking sharpness.

But what drew Sarah’s attention immediately were three women in the center of the photograph.

Three black women walking side by side down the middle of the street, wearing identical white dresses that seemed to glow against the darker tones of the surrounding scene.

They were captured midstride, their skirts swaying with movement, their postures confident and purposeful.

Sarah pulled the photograph closer, studying their faces.

The woman on the left was tall and slender, her head turned slightly toward the camera.

The woman in the middle was shorter, rounder, with a bright expression.

The woman on the right looked straight ahead, her expression serious, and focused.

All three had their hands positioned naturally as they walked, one adjusting her skirt, another at her side, the third lifted slightly.

But something about the image nagged at Sarah.

There was something deliberate about it.

Something that suggested this was more than just a casual street photograph.

She turned it over on the back in faded ink.

Royal Street, October 14th, 1899.

The three in white.

Back in her apartment in the Marin neighborhood, Sarah set up her highresolution scanner on the dining table.

She had invested in professional-grade equipment for her research, tools that allowed her to examine historical photographs with unprecedented detail.

She placed the photograph carefully on the scanner bed and initiated a scan at maximum resolution.

While the machine hummed and clicked, she opened her laptop and began searching historical databases for any reference to the three in white or to three black women in New Orleans in 1899.

The search yielded nothing specific.

She tried variations, women in white, Royal Street 1899, black women New Orleans, but found no matches.

The scanner beeped.

Sarah transferred the digital file to her computer and opened it in her photo analysis software.

She zoomed in slowly, methodically, starting with the women’s faces.

Even at high magnification, the image remained remarkably sharp.

The photographer had been skilled, capturing the scene with excellent focus despite the movement of the subjects.

She moved her examination to their hands.

The woman on the left had her right hand at her side, but her fingers were positioned unusually, not relaxed, but deliberately arranged.

Her thumb and index finger touched at the tips, forming a circle, while her other three fingers extended straight.

Sarah frowned and moved to the middle woman.

Her left hand was adjusting her skirt, but the fingers seemed deliberately positioned.

Her index and middle fingers were extended and separated, while her ring finger and pinky were folded against her palm, held down by her thumb.

The woman on the right had her right hand lifted slightly, palm facing away from the camera.

Her fingers formed another distinct configuration.

All five fingers spread wide.

Then the middle three folded down while the thumb and pinky remained extended.

Sarah sat back, her heart racing.

These weren’t random hand positions.

These were deliberate signals made while walking, captured in a photograph that had been carefully preserved and labeled.

She grabbed her notebook and began sketching the three hand positions, trying to determine if they followed any known sign language or code system from that era.

She spent hours searching through historical references to hand signals, secret societies, and coded communication systems used in the late 19th century.

Nothing matched exactly, but Sarah’s instincts told her she was on to something significant.

Three women walking together through the French Quarter in identical white dresses, making deliberate hand signals, signals important enough that someone had photographed them and preserved the image with a specific label.

She looked at the date again, October 14th, 1899.

There had to be something significant about that date.

She opened the New Orleans historical newspaper archives and began searching for October 1899, looking for any event that might explain why this photograph had been taken.

The Louisiana Research Collection at Tain University, opened at 8 a.

m.

, and Sarah was waiting at the door.

Dr.

Marcus Webb, the head archist and a colleague she had worked with on previous projects, greeted her with curiosity when she explained what she had found.

and let me pull the newspaper archives for October 1899,” he said, disappearing into the climate controlled stacks.

He returned with bound volumes of the Times Democrat and the Daily Picune.

Sarah began scanning through the additions from mid-occtober 1899.

On October 16th, 2 days after the photograph’s date, she found a small article buried on page 6.

Negro woman killed in Fourth Ward.

Marie Lavo, age 34, a negro residing on Burgundy Street, was found dead in her home Sunday evening.

Police report the death is suspicious.

Several neighbors reported seeing unknown white men in the vicinity earlier in the day.

No arrests have been made.

The article was brief and positioned among advertisements.

Sarah continued reading through subsequent days.

October 18th.

The death had been ruled a suicide.

Despite protests from family and neighbors, the case was closed.

October 20th.

A letter to the editor questioned the investigation.

October 22nd.

The police chief dismissed the concerns as inflammatory accusations.

Then nothing.

The story disappeared completely.

Marcus brought another box, materials from St.

Augustine Church in the TMA neighborhood.

In the funeral records from October 1899, Sarah found an entry for Marie Leavo’s service held on October 19th.

The entry noted that a large gathering of women from the community had attended and that three women in white dresses served as honorary paulbearers as per the wishes of the deceased.

Three women in white.

Sarah’s hands trembled as she continued through the church records.

She found two more funeral entries from late 1899 mentioning the three in white serving as honorary paulbearers.

In each case, the deceased was a black woman and in each case there were hints of suspicious circumstances.

Marcus returned with personal papers donated by descendants of Father Augustus Tebo, priest at St.

Augustine from 1895 to 1910.

Sarah opened his journal from 1899 and found an entry dated October 15th.

The day after the photograph, met today with the three sisters.

They came to report another death.

Marie L.

a good woman who spoke truth and paid the price.

The sisters show me their records, their careful documentation.

They have witnessed 17 deaths now.

17 women whose lives ended violently and whose justice was denied.

I’m humbled by their courage and horrified by their burden.

Sarah read the passage three times.

The three women in the photograph were documenting murders, violent deaths of black women whose killings were being covered up or ignored by authorities.

Sarah spent the following days immersed in Father T-Bolt’s journals.

The priest had been meticulous, and while he never recorded the women’s actual names, presumably to protect them, he described their work in increasing detail as his trust grew.

From the journals, Sarah learned that the network had begun in 1897.

After a series of murders of black women in New Orleans had gone uninvestigated by police, three women had decided that if official systems would not provide justice or acknowledgement, they would create their own system of documentation and memory.

They developed hand signals that could be made naturally, incorporated into everyday gestures, adjusting a skirt, brushing back hair, reaching for something so they could communicate in plain sight without drawing attention.

The signal served multiple purposes.

To identify members of the network to each other, to indicate when a death had occurred and been witnessed, and to mark locations where violence had taken place.

Father T-Bolt’s entry from November 3rd, 1899 provided crucial detail.

Another death.

The sisters were there.

They saw everything.

They made their witness sign as the woman died, so she would know someone was remembering, someone was recording the truth.

A March 1900 entry revealed the network’s full scope.

The sisters have revealed to me the full extent of their organization.

They are not alone.

There are others.

Dozens of women throughout the city, all trained to make the witness signs, all documenting the deaths that white newspapers refuse to report and police refuse to investigate.

Each sign has meaning.

One for I witnessed this death, another for justice was denied.

A third for the truth is recorded.

Uh they teach these signs to other women, creating a living archive of testimony that cannot be destroyed because it exists in memory and gesture rather than on paper that can be burned.

Sarah returned to the photograph with new understanding.

She examined the hand signals again, now knowing they weren’t random.

The woman on the left, thumb and index finger forming a circle, three fingers extended, that was witness.

the the middle woman, index and middle finger separated, others folded.

That was justice denied.

The woman on the right, thumb and pinky extended, middle fingers folded.

That was truth recorded.

The three women were making all three signs simultaneously as they walked down Royal Street on October 14th, 1899.

They were declaring their purpose, their mission, their defiance, and someone who understood had photographed them, preserving this moment of silent testimony.

Sarah contacted Dr.

Rebecca Chen, a colleague at Tain, who specialized in forensic photography and digital image enhancement.

When Sarah explained what she had discovered, Dr.

Chen immediately agreed to help analyze the photograph using advanced technology.

In Dr.

Chen’s laboratory, they began with spectral imaging using different wavelengths of light to reveal details invisible to the naked eye.

As the computer processed the data, additional layers of the photograph emerged.

“Look at this,” Dr.

Chen said, adjusting the display.

There are more people making hand signals in this photograph.

Sarah leaned closer.

In the background, partially obscured by the three women in white, other figures became visible.

A woman standing in a doorway, her hand positioned at her throat.

Another signal.

A man on the corner, his fingers arranged in a specific pattern.

A woman in a second story window, her hand visible through the glass, making yet another sign.

The entire street was communicating, Sarah whispered.

This wasn’t just three women.

This was a network operating in broad daylight.

Dr.

Chen zoomed in on different sections of the photograph, enhancing each figure.

They counted at least 12 other people making recognizable hand signals.

Some signals were the same as those made by the three women in white.

Others were different, suggesting a more complex vocabulary of gestures.

Dr.

Chen then focused on the storefront windows visible in the photograph.

Using reflection analysis, she was able to enhance what was visible in the glass.

In one window, the reflection showed another group of people across the street, also making signals.

In another window, text was barely visible.

a notice or poster of some kind.

She enhanced the text until it became legible.

Meeting Thursday, 8:00 p.

m.

St.

Augustine.

The date on the poster was October 12th, 1899.

2 days before the photograph was taken.

They were organizing.

Sarah said the photograph was taken 2 days after a meeting.

Maybe this was a demonstration of their network, a way of showing how many people were involved.

Dr.

Chen moved her analysis to the three women in white specifically.

She examines their clothing with enhanced detail, looking for anything that might provide additional information.

On the hem of the middle woman’s dress, barely visible, were dark stains that Spectral Analysis identified as blood.

She had been at a scene of violence recently, Dr.

Chen said quietly.

Probably the death of Marie Lavo on October 14th.

She went directly from witnessing that death to walking in this photograph.

They examined the faces of the three women again, now with maximum enhancement.

Their expressions, which had seemed serene at first glance, revealed something different under close scrutiny.

There was determination in their eyes, yes, but also grief, also anger, also exhaustion.

These were women who had witnessed horrors, who carried the weight of 17, now 18, deaths that no one else would acknowledge.

Marcus Webb called Sarah 3 days later with news.

I found something in the arch diosis and archives.

A locked box in the Saint Augustine materials labeled Father Tibo personal do not open.

The arch diocese finally gave me permission to access it.

Sarah met him at the archives within the hour.

The box was small, made of dark wood with a simple lock that had rusted over the decades.

Inside, wrapped in oil cloth, was a leatherbound notebook.

Father T-Bolt’s handwriting filled the pages, but the content was coded.

Names represented by initials, locations by symbols, dates by a numerical system that took Sarah hours to decipher.

But gradually, the pattern emerged.

The notebook contained a complete record of the deaths documented by the three sisters and their network.

Each entry included the victim’s initials, the date of death, the location, the circumstances, and most importantly, the names or descriptions of the perpetrators.

Sarah’s hands shook as she read through the entries.

Marie Lavo, ML, October 14th, 1899.

Cause: beaten to death.

Perpetrators: Three white men, names known to witnesses.

Police response: ruled suicide.

Case closed.

The entries went back to January 1897 and continued through December 1904.

83 deaths in total.

83 black women whose murders had been ignored, covered up, or deliberately mclassified by authorities.

But the notebook contained more than just death records.

Father Tibo had also documented the network itself.

He had created a key to the hand signals explaining what each gesture meant.

There were over 30 different signs allowing for complex communication.

Witness present.

Thumb and index finger forming circle.

Three fingers extended.

Justice denied.

Index and middle finger separated.

Others folded.

Truth recorded.

Thumb and pinky extended.

Middle fingers folded.

Danger present.

All fingers folded except index pointing down.

Safe house available.

Palm open, fingers spread, moved in circular motion.

Meeting location, fingers interlaced, thumbs crossed.

The list continued documenting an entire language created by and for black women in New Orleans.

A language that allowed them to communicate vital information while appearing to make ordinary gestures.

Father Tibolt had also recorded the names of the three founders, the women in white.

Sarah’s breath caught as she read them.

Celeste Rouso, age 31.

Lundress Josephine Dea, age 28.

Seamstress Marie Clair Dubois, age 33, midwife.

Finally, they had names.

The three women who had built this extraordinary network, who had witnessed and documented 83 murders over seven years, now had their identities restored to history.

Father TB’s notebook revealed the dangerous reality of what Celeste, Josephine, and Murray Clare had undertaken.

Several entries documented close calls, moments when they had nearly been discovered.

July 1898.

C followed by two white men after witnessing death on Rampart Street.

Lost them in the quarter.

Must be more careful.

March 1899.

Police questioned Jay about her presence at multiple death scenes.

She claimed to be visiting different friends.

They were suspicious but had no evidence.

September 1899.

MC threatened by family member of perpetrator.

He knows she saw something.

The sisters have decided to continue despite the danger.

The notebook also contained letters that had been tucked between pages, correspondence between Father Tibo and other priests, abolitionists, and activists in northern cities.

The three women had not been working in isolation.

They had connections to a broader network of people documenting racial violence across the South.

One letter dated November 1899 was from a journalist in New York named Frederick Willis.

He wrote, “The documentation you have sent is extraordinary.

These women are creating an archive that future generations will desperately need.

When the time is right, when it is safe, their testimony must be published.

The nation must know what is happening in cities like New Orleans.

But that time had never come while the women were alive.

The documentation had remained hidden, protected by Father T-Bolt and his successors, waiting for someone like Sarah to uncover it.

Sarah found entries describing how the network expanded.

By 1900, there were over 50 women involved, spanning multiple neighborhoods in New Orleans.

They had created safe houses where women fleeing violence could hide.

They had established connections with blackowned businesses that would provide employment and protection.

They had even created a system for helping women leave the city entirely when necessary.

The photograph from October 14th, 1899 took on new significance.

It wasn’t just documentation of the three founders.

It was a demonstration of power, a declaration that they existed and would not be silenced.

They had walked down Royal Street in broad daylight, making their witness signs, showing that their network operated in plain sight while remaining invisible to those who refused to see.

Father Tolt’s entry from October 15th, 1899 confirmed this interpretation.

The sisters walked yesterday with their signs visible, accompanied by dozens of others making their own signs throughout the quarter.

A photographer who understands their work captured the moment.

They tell me this photograph is for the future, for a time when their testimony can finally be heard.

With names finally identified, Sarah began searching for descendants of Celeste Rouso, Josephine Devo, and Marie Cla Dubois.

She started with census records, birth certificates, death certificates, and church records from New Orleans and surrounding areas.

Celeste Rouso had married in 1901 to a man named Thomas Baptiste.

They had four children between 1902 and 1910.

Sarah traced the family line forward through census records and found living descendants in New Orleans and Baton Rouge.

Josephine Deero had never married, but she had raised her sister’s three children after the sister died in 1903.

Another death documented in Father Tibol’s notebook.

Those children had taken Josephine’s surname and their descendants were traceable through Louisiana records.

Murray Clare Dubois had married twice.

First to a man who died in 1900, then to a ship captain named Jean Forier.

She had two children from her second marriage.

Her descendants had spread across the country with family branches in Texas, California, and Illinois.

Sarah located contact information for several great great grandchildren of each woman and began reaching out carefully, explaining her research and what she had discovered.

The first to respond was Patricia Baptiste, aged 72, living in the Tmaine neighborhood, the same neighborhood where St.

Augustine Church still stood.

She was Celeste’s great great granddaughter.

They met at a coffee shop near the church.

Sarah brought copies of the photograph, the enhanced images and relevant excerpts from Father Tolt’s notebook.

Patricia stared at the photograph for a long time, tears streaming down her face.

I’ve heard stories, she said quietly.

My grandmother used to tell me that her grandmother, Celeste, had done important work, dangerous work to protect women in the community, but she never explained exactly what it was.

She said it was safer for us not to know the details.

Ah, she touched the image gently.

Celeste lived to be 78 years old.

She died in 1944 when my mother was a teenager.

She never talked about what she had done.

My mother said she seemed to carry a great sadness, but also a great strength.

Sarah showed her the enhanced images, revealing the hand signals in the network of people throughout the street.

Patricia’s hands trembled as she realized the scope of what her ancestor had built.

“She was a hero,” Patricia whispered.

“All those women whose death she documented, she made sure they weren’t forgotten.

” Over the following weeks, Sarah connected with descendants of all three women.

She organized a gathering at St.

Augustine Church inviting family members to see the photograph and learn about their ancestors extraordinary work.

15 people attended, descendants of Celeste, Josephine, and Mary Clare, ranging in age from their 30s to their 80s.

Many met each other for the first time, discovering that their ancestors had been partners in this dangerous vital work.

Sarah presented her research methodically, starting with the photograph and explaining how she had decoded the hand signals, discovered Father T-Bolt’s records, and traced the full extent of the witness network.

She projected the enhanced images on a screen showing the dozen other people making signs throughout the street scene.

Your ancestors created something remarkable, Sarah said.

They built a system for documenting violence and injustice that the official power structures refused to acknowledge.

They witnessed 83 deaths over seven years.

They comforted the dying, supported the grieving, and made sure that each woman’s life and death was recorded and remembered.

She showed them excerpts from Father Tibolt’s notebook, including the descriptions of Celeste, Josephine, and Marie Cla’s courage and dedication.

She explained how the network had expanded, how it had saved lives, how it had operated in plain sight while remaining invisible to those who would have destroyed it.

Marcus Webb, who had helped with the research, spoke about the historical significance.

This is one of the most important discoveries in our understanding of black women’s resistance networks in the postreonstruction south.

Your ancestors created an entire infrastructure of witnessing, memory, and mutual protection.

They documented atrocities that would have been completely erased from history.

Dr.

Chen presented the technical analysis, showing how modern technology had revealed details invisible for over a century.

She explained how the hand signals had been designed to be made naturally, incorporated into everyday movements, creating a language that could be used openly without detection.

The families asked questions, shared stories they had heard from older relatives, and pieced together fragments of family memory that suddenly made sense in light of Sarah’s discoveries.

Several people mentioned that their grandmothers or great-grandmothers had used specific hand gestures that the family had always found curious but never understood.

Patricia Baptiste spoke last.

My grandmother told me something when I was young that I never forgot.

She said, “We come from women who refuse to let evil have the last word.

” I didn’t know what she meant then.

Now I understand.

Celeste and her sisters, because that’s what they were, sisters in purpose.

They witnessed horror, but they transformed that witnessing into power.

They made sure the truth survived.

Three months after the family gathering, Sarah’s research was published in the Journal of African-American History, accompanied by an exhibition at the New Orleans African-American Museum, the photograph of the three women in white became the centerpiece, displayed alongside the enhanced images revealing the network of signals throughout the street.

The exhibition included Father T-Bolt’s notebook displayed in a climate controlled case open to the page on listing the three founders names.

Beside it were the 83 names of the women whose deaths had been documented.

Women whose murders had been officially ignored or mclassified, but who had been remembered and honored by the witness network.

The exhibition explained the hand signals in detail, teaching visitors the language that Celeste, Josephine, and Mary Clare had created.

Interactive displays allowed people to practice making the signals, understanding how they could be incorporated into natural gestures.

Many visitors were moved to tears, realizing how black women had created systems of communication and protection that had operated invisibly for years.

National media covered the story, and the photograph went viral online.

People were stunned by the revelation that what appeared to be a simple street scene actually documented an extensive network of resistance.

The image was shared millions of times with many people noting that they had looked at the photograph initially without seeing anything unusual.

Proof of how effectively the women had hidden their work in plain sight.

Descendants of the 83 documented victims began coming forward, many learning for the first time how their ancestors had truly died.

The exhibition created a space for them to honor their family members whose deaths had been officially erased or distorted.

Patricia Baptiste and other descendants of the three founders became advocates for acknowledging this hidden history.

They worked with local schools to develop curriculum about the witness network, ensuring that new generations would learn about these women’s courage and ingenuity.

The photograph itself was donated to the New Orleans African-American Museum, where it became part of the permanent collection.

A plaque beside it read, “Celeste Rouso, Josephine Devo, and Marie Cla Dubois.

Royal Street, October 14th, 1899.

The three and white, founders of the witness network, which documented racial violence and created systems of protection for black women in New Orleans from 1897 to 1904.

Their work ensured that 83 women whose deaths were officially ignored would be remembered and honored.

The hand signals they are making visible to those who understand, declare, “We witness, we remember, we record the truth.

” Sarah’s final act was to create a digital archive of all the research, making it freely available to scholars, educators, and the public.

The archive included highresolution scans of the photograph with annotations explaining each hand signal, transcriptions of Father Tibolt’s notebook, family histories of the three founders, and documentation of the 83 women they had honored through their witnessing.

One year after the exhibition opened, the city of New Orleans installed a memorial in Congo Square near St.

Augustine Church.

Bronze statues of three women in white dresses stood together, their hands positioned in the witness signs.

At the base were engraved the names of Celeste, Josephine, and Marie Clair, along with the 83 women they had remembered.

The memorial became a gathering place for the community, particularly for women’s groups and activists continuing the work of witnessing and documenting injustice.

People would visit and practice making the hand signals, keeping the language alive, honoring the legacy of women who had refused to let violence and erasure have the final word.

Patricia Baptiste attended the memorial dedication with her family.

As she stood before the bronze statues, she made the three signals her ancestor had made.

Witness, justice denied, truth recorded.

Around her, dozens of other descendants did the same.

Their hands moving through the gestures that had once been secret, but were now proudly displayed.

The photograph that had seemed like nothing more than three friends walking down a street had revealed itself to be a testament to resistance, ingenuity, and the power of women who insisted on being heard even when the world tried to silence them.

Their silent signals captured in that moment in 1899 had finally found their

News

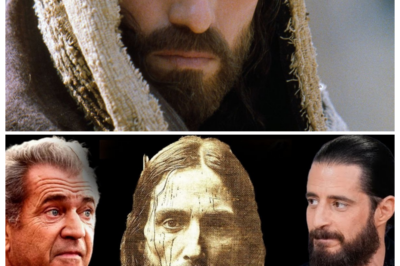

🎭 “I CARRIED THE CROSS OFF CAMERA TOO” — JIM CAVIEZEL FINALLY BREAKS HIS SILENCE ABOUT THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST AND REVEALS THE PAIN THAT NEVER STOPPED 🔥 In a trembling confession years after the cameras stopped rolling, Caviezel describes lightning strikes, broken bones, and eerie accidents that shadowed the set, hinting the suffering didn’t end with “cut,” but followed him home like a curse, leaving him wondering whether the role changed his soul forever 👇

The Silent Echoes of Truth In the dimly lit room, Jim Caviezel sat alone, shadows dancing across the walls. The…

🔥 “THEY DIDN’T WANT YOU TO READ IT” — MEL GIBSON CLAIMS THE ETHIOPIAN BIBLE WAS ‘BANNED’ AFTER CHURCH LEADERS DISCOVERED PASSAGES TOO POWERFUL TO CONTROL 📜 In a tense, late-night interview, Gibson alleges ancient texts hidden for centuries contain forbidden prophecies, missing books, and teachings that challenge everything modern Christianity was built on, warning that once believers see what was removed, “faith will never look the same again” 👇

The Forbidden Pages of Faith In the shadowy corridors of history, where whispers of the past linger like ghosts, Mel…

⚰️ MEL GIBSON STUNNED SILENT AS LAZARUS’ TOMB IS FINALLY OPENED — WHAT ARCHAEOLOGISTS FOUND INSIDE LEFT THE CREW TREMBLING 💥 Cameras roll as stone is moved for the first time in centuries, dust rising like smoke, and Gibson reportedly freezes mid-step, staring into the darkness as whispers spread that what lies inside doesn’t match anything historians expected, turning a biblical legend into a chilling, heart-pounding discovery that feels more like prophecy than history 👇

The Tomb of Secrets: A Hollywood Revelation The Unveiling of Lazarus: A Revelation That Shook the World In the heart…

🩸 JONATHAN ROUMIE & MEL GIBSON BREAK DOWN IN TEARS OVER THE SHROUD OF TURIN — HOLY RELIC SPARKS RAW CONFESSIONS AND SHOCKING REVELATIONS 💥 What began as a calm discussion turns into an emotional storm as the two stars speak with trembling voices about faith, doubt, and the weight of portraying Christ, their words hanging heavy in the air like incense, leaving viewers stunned as Hollywood meets holiness in a moment that feels less like an interview and more like a reckoning 👇

The Veil of Secrets In the dim light of a forgotten chapel, Jonathan Roumie stood before the ancient relic, the…

🩸 MEL GIBSON BLASTS THE VATICAN — “THEY’RE LYING TO YOU ABOUT THE SHROUD OF TURIN!” — HOLY RELIC ROW ERUPTS INTO GLOBAL FIRESTORM 🔥 Cameras barely start rolling before Gibson leans in, voice shaking with fury, claiming centuries of “carefully managed truth” and hinting that what believers were shown isn’t the whole story, sending historians scrambling, priests bristling, and millions wondering if the world’s most sacred cloth hides secrets too explosive for daylight 👇

The Shroud of Secrets Mel Gibson stood at the edge of a precipice, the weight of centuries pressing down on…

🕊️ POPE LEO JUST REVEALED THE TRUTH ABOUT THE 3RD SECRET OF FATIMA — MILLIONS STUNNED AS VATICAN FALLS INTO SILENCE AND BELLS STOP MID-CHIME 💥 What was supposed to be a quiet theological address turns into a jaw-dropping moment of history as the pontiff allegedly unveils details long whispered about for decades, cardinals freeze in their seats, cameras shake, and believers clutch their rosaries as if the sky itself just cracked open 👇

The Shattering Revelation of Pope Leo XIV In a world where faith often intertwines with doubt, the name Pope Leo…

End of content

No more pages to load