This portrait of two friends seemed harmless until historians noticed a forbidden symbol.

The afternoon sun filtered through the tall windows of the Chicago History Museum as Dr.Maya Johnson carefully unpacked another box from the Whitfield Estate collection.

It was September 2024 and she had been cataloging donations for nearly 3 weeks.

Her back achd from bending over archival boxes, her eyes strained from examining faded documents and fragile photographs.

This particular collection had arrived from the estate of Agnes Whitfield, a local civil rights activist who had passed away at 94.

Most of the contents documented the 1960s movement, protest signs, newsletters, correspondents.

Maya had already processed 12 boxes of invaluable material.

She was reaching for her coffee when her fingers brushed against a small wooden frame tucked beneath tissue paper at the bottom of box 13.

Mia pulled it out carefully, her archavist instincts immediately alert to its age.

The photograph was mounted on heavy cardboard backing, the kind used by professional studios in the late 19th century.

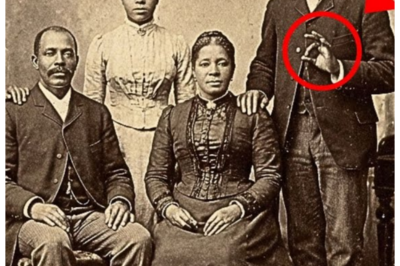

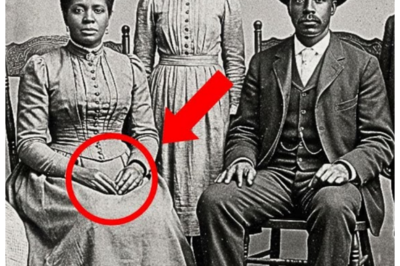

The image showed two young black women, both appearing to be in their early 20s, posed side by side in a formal studio setting.

The sepia tones had faded to warm browns, but the image remained remarkably sharp.

Maya’s breath caught.

Photographs of African-American women from this era were rare, but this one had exceptional quality.

Both women wore elegant dark dresses with high collars and long sleeves.

Their hair styled in the Gibson girl fashion popular around 1900.

Their expressions were serious but dignified, their postures upright.

The woman on the left was slightly taller with sharper features and eyes that seemed to challenge the camera.

The woman on the right had softer features, a gentler expression, but the same unmistakable dignity.

Their hands were positioned carefully.

The taller woman’s right hand rested on an ornate chair, while the other woman’s left hand held a small book.

Maya turned the photograph over.

On the back, written in faded ink, Lorraine and Victoria, Chicago, 1900.

No surnames, no other context, just two first names and a year.

She turned on her desk lamp and studied the details.

The studio backdrop showed painted columns and draped fabric typical of the period.

The women’s clothing was expensive, silk or fine wool with intricate details suggesting skilled tailoring.

These were not poor women.

These were women of means, education, status.

Mia reached for her phone to take a reference photo.

As she adjusted the angle to minimize glare, something caught her eye.

On the collar of the taller woman’s dress, partially obscured by shadow, but visible when light hit correctly, was something embroidered into the fabric, a symbol.

Maya sat down her phone and retrieved a magnifying glass.

The embroidery was small, no more than half an inch in diameter, done in thread, matching the dress so closely it was almost invisible, but it was definitely there.

Deliberate, carefully crafted.

The symbol showed a circle with a star inside and beneath it two crossed lines.

Mia had seen the symbol before in her research.

But where? Mia sat at her desk long after her colleagues had left.

The photograph positioned under her highintensity lamp.

She had spent three hours searching through reference books and digital archives, trying to place the symbol embroidered on Lraine’s collar.

The museum was quiet except for the hum of climate control and occasional footsteps of security guards.

Maya’s coffee had gone cold, but she barely noticed.

She had photographed the symbol, transferred it to her computer, and enhanced it using the museum’s digital software.

The enhancement revealed details invisible to the naked eye.

The stitching was too precise to be merely decorative.

The circle was perfect.

The star inside had five points, and the crossed lines beneath formed an X.

Maya opened a reference book titled Secret Societies and Resistance Networks in Post Reconstruction America.

Uh, she flipped through pages, scanning illustrations and photographs.

Most symbols were associated with fraternal organizations.

mutual aid societies, labor unions.

Many were innocent, representing brotherhood or charity.

Then on page 247, she found it.

The symbol matched almost exactly a circle containing a five-pointed star with crossed lines beneath.

The caption read, “Symbol of the Daughters of the Star, an underground network of African-American women activists operating between 1895 and 1910.

” The organization was considered sedicious by authorities due to its advocacy for voting rights, education access, and resistance to Jim Crow laws.

Members faced arrest, violence, and economic retaliation if discovered.

Maya read the paragraph three times, her heart racing.

The Daughters of the Star.

She had never heard of them.

Remarkable given her expertise.

Most secret societies from this era had been documented, their activities recorded even if membership lists were lost.

But this organization was different.

The book noted records were fragmentaryary at best, most documentation deliberately destroyed by members to protect their identities, and modern historians have struggled to verify the extent of the network’s activities.

The book included only two references.

A newspaper article from 1902 mentioning a dangerous society of colored women spreading radical ideas and a police report from 1905 describing a raid on a Chicago home where sedicious materials in a flag bearing a star symbol were confiscated.

Maya turned back to the photograph.

If Lorraine wore the Daughters of the Star symbol openly enough to be captured in a photograph, even barely visible, it meant either she was extraordinarily bold, or the photograph was intended only for others within the organization.

She studied Victoria’s image more carefully, looking for similar markings.

Victoria’s collar was turned differently, less visible.

But Maya could see what appeared to be a small brooch pinned near her throat.

The brooch was difficult to make out, but it appeared circular with something at its center.

Another version of the symbol.

Maya checked the time.

nearly 900 p.

m.

She should go home, start fresh tomorrow.

But the photograph held her.

These two women had posed in 1900 wearing symbols that could have gotten them arrested.

Who were they? What had they done? And why had this photograph survived when so many records had been destroyed? Tomorrow, she would visit the archives and begin tracing their stories.

Maya arrived at the Chicago Public Libraryies Special Collections Division at 8:30 the next morning, coffee in hand and laptop bag over her shoulder.

She had barely slept, her mind spinning with questions about Lorraine and Victoria.

The reading room was already occupied by researchers hunched over manuscripts and microfilm readers.

Maya signed in and requested the African-American community records collection, specifically materials from 1895 to 1910.

While waiting, she opened her laptop and searched digital newspaper archives.

She started with Chicago Papers from 1900, searching for Daughters of the Star or similar women’s organizations.

The search returned thousands of results for various women’s clubs, church groups, literary circles, charity organizations.

The African-American community in Chicago at the turn of the century had been vibrant with dozens of institutions serving the growing population.

Maya refined her search, adding terms like sedicious, radical, voting rights.

The results narrowed considerably.

In the Chicago Defender Archives, she found a brief mention from August 1901.

Several prominent colored women were questioned by police yesterday regarding their involvement in activities deemed inappropriate for their station.

The women denied any wrongdoing and were released without charges.

Sources suggest the investigation relates to distribution of pamphlets advocating for suffrage and education reform.

No names given, no organization mentioned, but the date was right and the description matched.

A librarian approached with a cart.

Dr.

Johnson, these are the materials you requested.

Please handle them carefully.

Some are quite fragile.

Maya thanked her and began working through the boxes.

Most contained church records, business directories, social club minutes, valuable materials, but not what she needed.

Then in the fourth box, she found something that made her pulse quicken.

A membership book from the IDB Wells Women’s Club, dated 1899 1903.

The club had been one of Chicago’s most prominent African-American women’s organizations.

Maya carefully turned the fragile pages, scanning handwritten names and notes.

The entries listed members names, addresses, occupations, and committee assignments.

On a page dated March 1900, she found it.

Lorraine Mitchell, teacher Westside, committee education reform.

And two lines below, Victoria Davis, seamstress, southside, committee, education reform.

on a Lraine and Victoria.

The names from the photograph, both assigned to Education Reform, both listed in March 1900, the same year as the photograph.

Maya’s hands trembled as she photographed the page.

This was them.

But membership in the Ida Be Wells Club was perfectly legal, publicly acknowledged.

Why would they need secret symbols? She continued reading.

Over the next pages, she noticed something odd.

Certain members had small marks next to their names, tiny dots or dashes that could be mistaken for ink smudges, but they appeared too regularly, too deliberately placed.

Maya counted them.

17 women across the membership list had these marks.

Lorraine Mitchell and Victoria Davis were both among them, a code within official records, a way to identify members of something hidden within the legitimate organization.

The Daughters of the Star hadn’t been separate.

They had operated inside respectable women’s clubs, hiding in plain sight.

Maya spent the afternoon at the National Archives research facility examining 1900 census records for Chicago.

Now that she had surnames Mitchell and Davis, she could trace Lorraine and Victoria’s lives more completely.

The census records were handwritten, sometimes difficult to read.

But Maya had years of experience deciphering 19th century script.

She found Lorraine Mitchell listed in the enumeration for Chicago’s Third Ward, an area on the west side with a significant African-American population.

Lorraine Mitchell, age 24, female, black.

Occupation: teacher, literate, born in Illinois, living in a boarding house with four other women, all employed professionally.

24 years old in 1900, born around 1876, the first generation born after slavery’s end, coming of age during Jim Crow’s brutal backlash.

A teacher meant significant education, rare and precious for a black woman.

Then Maya found Victoria Davis in the seventh ward census, Southside.

Victoria Davis, age 22, female, black occupation, dressmaker, literate, born in Tennessee, living with her mother and two younger siblings, 22 in 1900, born around 1878 in Tennessee.

She had migrated north, possibly fleeing uh the intensifying segregation and violence, a dress maker with her own trade, supporting her family.

Both women were young, educated, employed, independent.

Both were part of Chicago’s small but growing black middle class.

women who had opportunities their parents’ generation could barely imagine.

And both were apparently members of a secret activist network advocating for voting rights and resistance to Jim Crow, activities that could get them fired, evicted, or worse.

Maya pulled additional records.

City directories from 1900 showed Lorraine Mitchell teaching at the Douglas School, a segregated elementary school serving black children on the west side.

Victoria Davis operated a dressmaking business from her home.

Maya leaned back, thinking both women had positions requiring respectability.

Lorraine taught children.

Any hint of radicalism could cost her that position.

Victoria served clients who expected propriety.

Yet, they had taken the extraordinary risk of wearing the daughters of the star symbol in a photograph.

Maya checked the time, nearly 5:00 p.

m.

Before leaving, she made one more search.

She looked for police records, arrest records, anything showing what happened to women caught in Daughters of the Star activities.

What she found made her stomach clench.

In 1902, a woman named Sarah Thompson had been arrested in Chicago for distributing sedicious materials and inciting unrest among the colored population.

The materials were pamphlets advocating for voting rights.

Sarah Thompson was a teacher.

She lost her job, was fined heavily, and eventually left Chicago, whereabouts after 1903 unknown.

In 1905, three women in St.

Louis were arrested on similar charges.

All were members of a women’s literary club.

All lost employment.

One was forcibly committed to an asylum by her employer who claimed she showed dangerous delusions.

The risks were real, consequences devastating.

The daughters of the star weren’t playing at activism.

They were putting everything on the line.

Maya looked at the photograph on her phone at Lraine and Victoria standing dignified, the forbidden symbol barely visible.

What had driven them to take such risks? And what happened to them after 1900? Maya returned to the museum determined to find living descendants of Lorraine Mitchell or Victoria Davis who might have family records, photographs or stories passed down through generations.

She started with genealogy databases tracing Lraine and Victoria forward from 1900.

The trail was difficult.

Many records from this era were incomplete, especially for African-American families.

But Maya was persistent.

After 2 days of searching, she found a marriage record from 1903.

Lorraine Mitchell married to James Parker, a Pullman porter.

No children listed in subsequent census records.

The couple appeared in Chicago directories until 1918, then vanished.

Victoria Davis’s trail was clearer.

She married in 1905 to Robert Thompson, a postal worker.

They had three children between 1906 and 1912.

The family remained in Chicago, appearing in records through the 1940s.

Maya focused on Victoria’s line, tracing descendants forward.

One of Victoria’s daughters, named Lorraine, clearly after her mother’s friend, had married and had children.

That line continued generation after generation.

After hours of careful research, Maya found a name that made her pause.

Professor Evelyn Thompson, age 68, living in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood.

According to her university faculty page, she was a retired history professor specializing in African-American women’s history.

Victoria Davis’s great great granddaughter was a historian.

Maya’s hands shook as she composed an email introducing herself, explaining about the photograph, asking if Professor Thompson would meet.

She included a scan showing Victoria and Lorraine in 1900.

The response came within two hours.

Dr.

Johnson, I’ve been waiting my entire career for someone to ask about that photograph.

Yes, I know who these women were.

Yes, I know about the symbol.

And yes, there is much more to the story.

Can you come to my home tomorrow at 2 p.

m.

? Maya’s heart raced as she typed confirmation.

The next afternoon, she drove to a gracious Greystone building in Hide Park.

Professor Thompson answered the door herself, a tall, elegant woman with silver hair and sharp, intelligent eyes that reminded Maya immediately of Victoria’s expression in the photograph.

“Dr.

Johnson,” she said, extending her hand.

“Welcome, please come in.

” The apartment was filled with books, photographs covering every wall, documents carefully preserved in frames.

Maya recognized immediately she had entered the home of someone who understood history’s value.

Professor Thompson led her to a sitting room where afternoon light streamed through tall windows.

on a coffee table set a leatherbound album clearly very old.

My great great grandmother Victoria kept meticulous records, Professor Thompson said, settling into a chair.

She knew the work they were doing was dangerous and that official records would likely be destroyed, so she created her own archive hidden in plain sight as a family photo album.

She opened the album carefully.

Inside were dozens of photographs, newspaper clippings, handwritten notes, pressed flowers, ribbons, small momentos, and on the first page, the same photograph Maya had found showing Lraine and Victoria in 1900.

They took this photograph deliberately, Professor Thompson said, pointing to the symbol on Lraine’s collar.

It was meant as a record, proof that the Daughters of the Star existed.

Professor Thompson turned the album pages slowly, each revealing pieces of a story deliberately hidden for over a century.

Maya photographed pages with permission documenting everything.

The Daughters of the Star began in 1895, Professor Thompson explained.

In the home of Elizabeth Garfield here in Chicago, Elizabeth was a widow, a businesswoman who owned a boarding house catering to professional black women, teachers, nurses, dress makers, women with education, but facing constant barriers.

She pointed to a newspaper clipping from 1895 showing an obituary.

When Elizabeth died in 1910, the papers called her a respected boarding house proprietor.

They had no idea her home had been headquarters of an underground network operating in eight cities.

Maya studied the clipping, noting the careful, neutral language, nothing hinting at Elizabeth’s true activities.

The organization had strict rules, Professor Thompson continued.

Members could not write down names or meeting locations.

All communication was verbal or coded.

The symbol star within a circle with crossed lines was worn only in ways explainable as ordinary decoration if questioned.

A brooch embroidered detail, a bookmarking.

She turned to a page showing fabric carefully preserved behind archival plastic.

The fabric had the star symbol embroidered in one corner.

This was from Victoria’s dressmaking business.

She sewed the symbol into garments for other members, always in hidden places, inside a collar, under a hem, places only visible if you knew to look.

It was identification, silent acknowledgement of shared purpose.

Maya remembered the symbol on Lorraine’s collar in the photograph, barely visible even with enhancement.

What was their purpose? What did they actually do? Professor Thompson’s expression grew serious.

They did everything forbidden to them.

They taught black women to read and write in secret classes held in homes and churches.

They distributed pamphlets advocating for voting rights and education access.

They documented lynchings and violence against black communities, sending reports to northern newspapers.

Uh, they helped women escape domestic abuse and find employment.

They organized boycots of businesses refusing to serve black customers.

She turned another page revealing a handwritten document.

This is Victoria’s diary from 1901.

She kept it in code using initials instead of names, vague references to locations, but the activities are clear.

Weekly meetings, educational sessions, planning actions.

Maya leaned forward, reading the faded script.

The entries were brief but revealing.

Met with L and three others.

distributed 20 pamphlets on State Street.

Close call with police.

Teaching session with six women.

L brought primer and slate.

Protest planned.

All agreed despite risks.

L had to be Lorraine.

The two women were close partners in this dangerous work.

What happened to them? Maya asked quietly.

Professor Thompson’s expression darkened.

In 1906, there was a major crackdown.

Police raided homes across Chicago, arrested dozens of women involved in what they called sedicious activities.

Many lost everything.

She turned to a newspaper clipping from March 1906.

The headline read, “Police dismantle radical women’s network.

” The article described arrests, confiscated materials, women charged with disturbing peace and inciting unrest.

“Maya scanned the names listed.

” “Victoria Davis was not among them.

Neither was Lorraine Mitchell.

” “They escaped,” Mia asked.

“They survived by making an impossible choice.

” Professor Thompson turned to a page containing a handwritten letter, paper yellowed and fragile.

This is a letter Victoria wrote to Lraine in April 1906, just after the raids.

They couldn’t meet, too dangerous.

So, they communicated through a trusted intermediary.

Maya read the careful script.

My dearest L, the storm has come as we feared.

Elizabeth’s house was raided three days ago.

They took everything.

Our materials, records, our flag.

Seven sisters were arrested.

We must decide now whether to continue or protect ourselves and our families.

I cannot bear to abandon the work, but I cannot bear to lose my children to an orphanage if imprisoned.

What shall we do? Professor Thompson produced another letter.

Lorraine’s response.

My dear V, my heart breaks with this choice.

I have spent sleepless nights weighing our duty to the cause against our duty to survive.

I believe we can do both, but not in the way we have been.

We must become invisible.

We must continue the work in ways that cannot be traced.

We teach in our regular positions and slip lessons of freedom into ordinary subjects.

We sew strength into garments.

We raise the next generation to be braver than we could be.

This is not surrender.

It is strategy.

Maya looked up at Professor Thompson.

They went underground completely.

They did more.

They transformed their activism into something appearing completely respectable.

Lorraine continued teaching but began emphasizing black history and literature in lessons despite it not being in the official curriculum.

She taught her students about Frederick Douglas and Sojourer Truth under the guise of reading comprehension.

Professor Thompson turned to another page showing a school photograph from 1908.

Lorraine stood with a class of young black children, all holding books.

She made sure every child could read fluently and knew their own history that was radical itself.

And Victoria, Victoria’s dressmaking business became a network.

She employed young black women, taught them the trade, paid them fair wages, and created economic independence for dozens of families.

She also continued sewing the symbol into garments for those who still wanted identification, but now so subtly that even if someone saw it, they would think it was decorative stitching.

Professor Thompson showed Maya a photograph of a dress from 1908.

Beautifully crafted.

Along the inner seam, barely visible, was the star symbol woven into the stitching pattern.

The daughters of the star didn’t disappear.

Professor Thompson said they evolved.

They became teachers, business women, mothers who raised children to fight for justice.

They became invisible revolutionaries.

Maya thought about the 1900 photograph taken before the raids, before the impossible choice.

The photograph was taken when they were still bold enough to wear the symbol openly, even if hidden.

Exactly.

That photograph is evidence of a brief moment when they believed they could be both visible and safe.

After 1906, no one would have dared.

But in 1900, they still had hope.

Professor Thompson closed the album gently.

Victoria kept this photograph her entire life.

She showed it to her children, told them stories about Lraine and the work they had done.

She wanted them to know their mother had fought for something larger than herself.

“What happened to Lraine?” Maya asked.

I found records showing she married James Parker in 1903, but the trail goes cold in 1918.

Professor Thompson’s expression grew sad.

Lorraine died in the 1918 influenza pandemic.

She was only 42.

Professor Thompson’s voice was quiet as she continued.

Victoria was devastated when Lorraine died.

She wrote in her diary that she had lost not just a friend, but a sister in the truest sense.

Lorraine left no children, so her legacy lived through the hundreds of students she taught and through Victoria’s family who kept her memory alive.

Maya felt the weight of these women’s lives settling over her.

They had risked everything.

Had to transform their activism to survive.

Had lost each other to illness and time, but they had persisted.

The photograph, Mia said slowly.

It’s the only visual evidence that they were part of the Daughters of the Star.

Yes, and that’s why it’s so important that you found it, Dr.

Johnson.

Over the next weeks, Mia worked closely with Professor Thompson to piece together the complete story.

They identified 12 other women who had been part of the network, tracing their stories through fragmented records, family histories, and coded diary entries.

Maya interviewed six descendants of network members, recording their family stories.

Each interview revealed new dimensions of how the organization had operated.

The secret signals members used to identify each other, the safe houses where meetings were held, the elaborate systems for distributing pamphlets without being caught.

She worked with the museum’s conservation team to preserve and display the original 1900 photograph, the fabric samples with the star symbol, Victoria’s diary, and the letters between Lorraine and Victoria.

Maya also reached out to historians at other institutions sharing her findings.

The response was overwhelming.

Several scholars who specialized in African-American women’s history expressed amazement that the Daughters of the Star had remained essentially unknown despite their extensive activities.

By February 2025, Maya had created an exhibition titled Hidden in Plain Sight: The Daughters of the Star and the Secret History of Women’s Resistance.

The centerpiece was the photograph of Lorraine and Victoria, displayed with digital enhancements that allowed visitors to see the barely visible symbol on Lraine’s collar.

Accompanying text explained who they were, what they had risked, and how they had transformed their activism to survive.

The night before the opening, Mia stood alone in the gallery, looking at the exhibition she had built.

The photograph of Lorraine and Victoria held pride of place, illuminated carefully to show both women’s dignity and the secret they had carried.

These women had risked everything for justice, had been forced to become invisible to survive, but had never stopped fighting.

And now, 125 years later, their story would finally be told.

Maya thought about the symbol, the star within a circle with crossed lines beneath.

It had been forbidden in 1900, dangerous to wear, capable of destroying lives if discovered.

But it had also been a declaration, “We are here.

We resist.

We will not be silent.

” The symbol had survived, hidden in a photograph, waiting over a century to reveal its meaning.

And in that survival was proof that no story, no matter how deliberately buried, stays hidden forever.

The exhibition opened on February 15th, 2025 to a crowd larger than Maya had anticipated.

The museum’s main gallery was filled with people, historians, community leaders, descendants of the Daughters of the Star, students, journalists, and curious visitors drawn by the story.

Professor Thompson arrived early, accompanied by five other descendants Maya had interviewed.

They gathered around the photograph of Lorraine and Victoria, some seeing it for the first time in person rather than in scans or reproductions.

My great great-grandmother stood right there.

Professor Thompson said softly, pointing to Victoria’s image.

She was 22 years old, already running her own business, already part of a network that would change lives, and she was terrified every single day that she would be discovered.

Maya watched as visitors moved through the exhibition, reading the text panels, examining the artifacts.

She had organized the display chronologically, starting with the founding of the Daughters of the Star in 1895, and moving through their most active years, the 1906 crackdown, and their transformation into invisible activists.

One section featured Victoria’s dressmaking tools alongside examples of garments she had made with the hidden star symbols carefully illuminated.

Another section displayed Lorraine’s teaching materials, a primer she had used, handwritten lesson plans that subtly incorporated black history, a class photograph from 1907.

The letters between Lorraine and Victoria were displayed side by side, allowing visitors to read the impossible choice they had faced.

continue openly and risk everything or transform their activism into something that appeared respectable while still fighting for justice.

A journalist from the Chicago Tribune approached Mia.

Dr.

Johnson, this is remarkable research.

How did you feel when you first discovered the symbol in the photograph? Maya considered the question.

I felt like I had found something that wasn’t meant to be lost.

These women went to great lengths to hide their activism, but they also left breadcrumbs.

the symbol in the photograph, Victoria’s coded diary, the marks in the membership book.

They wanted someone someday to find them and tell their story properly.

The journalist scribbled notes.

What do you think is the most important takeaway from this exhibition? That resistance takes many forms, Maya said.

We tend to think of activism as loud and public, but sometimes the most radical thing you can do is survive, teach the next generation, create economic opportunities, and refuse to be erased.

Lorraine and Victoria did all of that.

Throughout the afternoon, Maya gave several tours, explaining the research process, the significance of the artifacts, the context of the era.

She watched people’s faces as they learned about the risks these women had taken, the consequences they had faced, the ways they had persisted.

Professor Thompson gave a talk at 3 p.

m.

sharing family stories about Victoria that had been passed down through generations.

She spoke about how Victoria had lived until 1951, dying at 73, and how she had spent her final years telling her grandchildren about the work she and Lorraine had done.

She wanted us to know, Professor Thompson said, her voice carrying across the crowded gallery, that ordinary people can do extraordinary things when they refuse to accept injustice.

She wanted us to know that every small act of resistance matters, even when it seems invisible.

Betis.

The exhibition was scheduled to run for six months, but the response was so strong that the museum extended it to a full year.

Six months after the exhibition opened, Maya received an email that made her stop midsip of her morning coffee.

It was from a woman named Rachel Patterson in Philadelphia who had seen news coverage of the exhibition online.

Dr.

Johnson, I believe my great great-grandmother was also part of the Daughters of the Star.

I have a photograph from 1898 showing her wearing a brooch with the same symbol.

I never knew what it meant until I saw your exhibition.

Would you be interested in seeing it? Maya immediately replied yes.

Over the next weeks, she received 17 similar emails from people across the country.

Descendants who had family photographs, pieces of jewelry, embroidered items, or coded diaries that they now realized were connected to the Daughters of the Star.

The network had been far larger than Maya had initially discovered.

It had extended beyond Chicago to Philadelphia, Boston, Detroit, St.

Louis, and at least six other cities.

The organization had operated for 15 years from 1895 to 1910 involving potentially hundreds of women.

Maya began collaborating with historians in other cities, sharing research methods, comparing findings.

A picture emerged of a sophisticated multi-ity network of black women activists who had operated in absolute secrecy, advocating for voting rights, education access, and resistance to Jim Crow.

Decades before the mainstream civil rights movement, the Chicago History Museum created a digital archive collecting photographs, documents, and family stories from descendants across the country.

The archive grew to include materials from 43 women who had been part of the network.

Maya published her findings in the Journal of African-American History, and the article sparked intense academic interest.

Graduate students began writing dissertations on the Daughters of the Star.

Documentaries were planned.

The story that had been deliberately buried for over a century was finally receiving the attention it deserved.

But for Maya, the most meaningful moment came a year after the exhibition opened.

She received a letter from a 15-year-old girl named Jasmine, who had visited the exhibition with her school class.

Dear Dr.

Johnson, I saw the photograph of Lorraine and Victoria, and I cried.

I never knew that black women were fighting for our rights that long ago.

I never knew they had to hide what they were doing and could lose everything.

It made me think about my own grandmother who was in the civil rights movement in the 1960s and how she never talked much about it.

Now I understand why.

Thank you for finding them and telling their story.

It matters.

Maya kept that letter on her desk next to a reproduction of the 1900 photograph.

The photograph that had started everything.

Lorraine and Victoria standing dignified and serious.

The forbidden symbol barely visible on Lorraine’s collar.

Now hung in the museum’s permanent collection.

Visitors could see it any day.

could learn about the women who had risked everything, could understand that resistance and activism had always existed, even when deliberately hidden.

The star within a circle with crossed lines beneath, once a forbidden symbol that could destroy lives, had become a symbol of courage, persistence, and the refusal to be erased.

Maya stood in the gallery, one quiet Tuesday afternoon, looking at the photograph.

She thought about Lorraine teaching children to read while secretly teaching them about their own history.

She thought about Victoria sewing symbols into garments, creating economic independence for women, raising children to fight for justice.

They had been invisible revolutionaries, and now they were visible at last.

The story of the Daughters of the Star would never be completely recovered.

Too much had been deliberately destroyed, too many records lost.

But enough remained, enough to honor them, to remember them, to ensure that their courage was never forgotten.

“Maya smiled at the photograph.

” “We found you,” she whispered.

and we’re telling your story.

In the image, Lorraine and Victoria stood silent and dignified as they had for 125 years carrying their secret.

But the secret was a secret no longer.

The symbol had endured and with it the truth.

News

Experts Thought This 1910 Studio Photo Was Peaceful — Until They Zoomed In and Saw What the Girl Was Holding, and the Entire Room Went Cold 📸 — At first it looked like another gentle Edwardian portrait, lace dress, soft lighting, polite smile, but when archivists enhanced the image they noticed her tiny fingers clutching something oddly deliberate, something that didn’t belong in a child’s hands, and suddenly the sweetness curdled into dread as historians realized this wasn’t innocence… it was a clue 👇

Experts thought this 1910 studio photo was peaceful until they saw what the girl was holding. Dr.Maya Johnson’s hands trembled…

This Portrait from 1895 Holds a Secret Historians Could Never Explain — Until Now It’s Finally Been Exposed in Stunning Detail 🖼️ — For more than a century it hung quietly in dusty archives, dismissed as another stiff Victorian pose, until a routine scan revealed a tiny, impossible detail that made experts freeze mid-sentence, because suddenly the calm expressions looked staged, the shadows suspicious, and the entire image felt less like art… and more like evidence 👇

The fluorescent lights of Carter and Sons estate auctions in Richmond, Virginia, cast harsh shadows across tables piled with forgotten…

It Was Just a Studio Photo — Until Experts Zoomed In and Saw What the Parents Were Hiding in Their Hands, and the Room Went Dead Silent 📸 — At first it looked like another stiff, sepia family portrait, the kind you pass without a second thought, but when historians enhanced the image and spotted the tiny, deliberate objects clutched tight against their palms, the smiles suddenly felt forced, the pose suspicious, and the entire photograph transformed from wholesome keepsake into something deeply unsettling 👇

The auction house in Boston smelled of old paper and varnished wood. Dr.Elizabeth Morgan had spent the better part of…

This Forgotten 1912 Portrait Reveals a Truth That Changes Everything We Thought We Knew — and Historians Are Panicking Over What’s Hidden in Plain Sight 🖼️ — It hung unnoticed for over a century, dismissed as polite nostalgia, until one sharp-eyed researcher zoomed in and felt their stomach drop, because the face, the object, the posture all scream a secret no one was supposed to catch, turning a dusty archive into a ticking historical bombshell 👇

This forgotten 1912 portrait reveals a truth that changes everything we knew until now. Dr.Marcus Webb had been working as…

Four Years After The Grand Canyon Trip, One Friend Returned Hiding A Dark Secret

On August 23rd, 2016, 18-year-olds Noah Cooper and Ethan Wilson disappeared without a trace in the Grand Canyon. For four…

California Governor STUNNED as Amazon Slams the Brakes on Massive Expansion — Billions Vanish Overnight and a Golden-Era Promise Turns to Dust 📦 — What was supposed to be a ribbon-cutting victory lap morphs into a political nightmare as Amazon quietly freezes its grand plans, leaving empty lots, stalled cranes, and thousands of “future jobs” evaporating like smoke, while the governor stands blindsided, aides scrambling, and critics whispering that the tech titan just played the state like a pawn 👇

The Collapse of Ambition: A California Nightmare In the heart of California, where dreams are woven into the fabric of…

End of content

No more pages to load