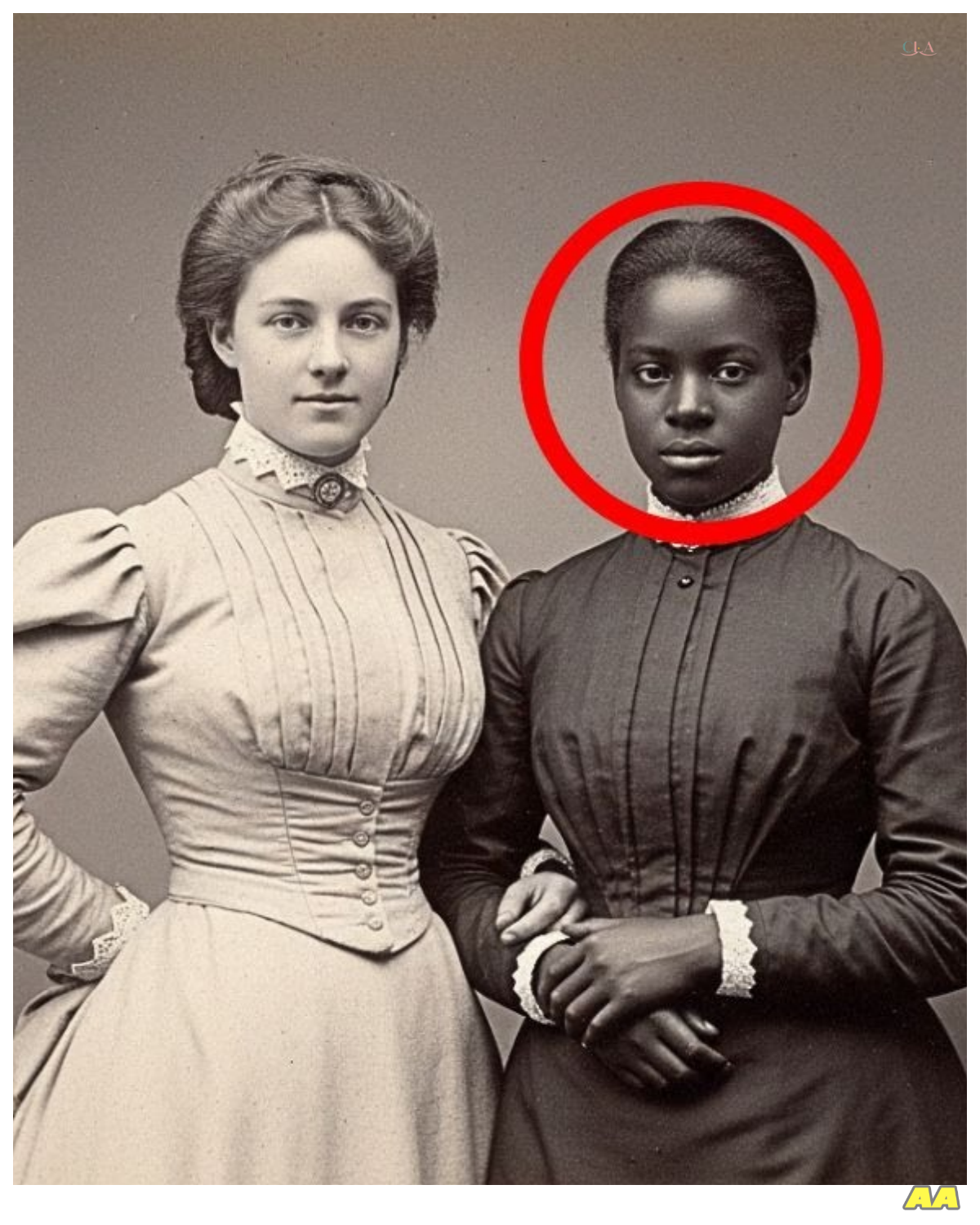

This photograph appeared to depict friendship — but the girl’s collar revealed something more

The rain drumed steadily against the windows of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington, DC.

Dr.Elena Rodriguez sat in her small office on the third floor, cataloging recent donations.

After 15 years as a curator specializing in post Civil War African-American history, she had developed an instinct for recognizing significant artifacts.

And today, something in the next donation box would prove that instinct correct.

She reached for a cardboard box postmarked from Savannah, Georgia.

Inside, wrapped carefully in acid-free tissue paper, was a single photograph mounted on thick card stock.

The moment Elena lifted it into the light, she knew this was unusual.

The image showed two young girls, approximately 14 to 16 years old, standing side by side in a professional photography studio, the painted backdrop depicted a garden scene with climbing roses.

Both girls wore elegant dresses with high collars, fitted bodesses, and long sleeves, expensive clothing typical of wealthy families in the 1880s.

The girl on the left was white with fair hair styled fashionably.

Her posture radiated confidence, one hand resting casually at her side.

The girl on the right was black with carefully arranged hair and hands folded formally in front of her.

They stood close together, their proximity suggesting some form of relationship.

Elena’s historian’s mind immediately registered the anomaly.

Formal photographs from 1880s Georgia showing black and white children posed together as apparent equals were extraordinarily rare.

The South in 1888 was three years away from piever Ferguson.

But racial segregation was already brutally enforced through custom law and violence.

She turned the photograph over written in faded brown ink was a single notation.

Margaret and Lily June 1888 Savannah.

No surnames, no additional context, just two first names and a date.

Elena pulled out her professional magnifying loop and examined the image more closely.

The photograph’s technical quality was excellent.

Sharp focus, proper exposure, careful composition.

This had been created by a skilled photographer, not an amateur.

Someone had paid significant money for this portrait.

But as Elena studied the girl’s faces, something began to trouble her.

The white girl, Margaret, looked directly at the camera with an easy, natural expression.

Her body language communicated comfort and belonging, but the black girl’s demeanor was markedly different.

Lily’s eyes were cast slightly downward, not quite meeting the camera’s gaze.

Her shoulders curved inward slightly.

Her hands, folded at her waist, were positioned in a posture that read as differential rather than relaxed.

Elena had examined thousands of historical photographs.

She knew how to read the subtle language of pose, expression, and body positioning.

And this photograph was telling her two different stories.

The surface story of two young companions and something darker underneath.

She reached for the donation letter that had accompanied the box.

Dear doctor Rodriguez, I found this photograph while clearing out my late grandmother’s attic in Savannah.

I believe it may have historical significance, though I don’t know the complete story behind it.

The image has always troubled me in ways I cannot fully articulate.

Perhaps your expertise can reveal what I sense but cannot see.

I trust you will handle whatever truth it contains with appropriate care.

Sincerely, Patricia Whitmore.

Elellanena read the letter twice, noting the careful phrasing, and whatever truth it contains.

Patricia Whitmore suspected something about this photograph, even if she couldn’t identify exactly what.

Elena picked up her phone and dialed her colleague, Dr.

Marcus Chen, a specialist in 19th century photography and material culture analysis.

Marcus, I need your expertise on something.

Can you come to my office? I think we may have found something significant.

Be there in 5 minutes, Marcus replied.

Ellena returned to the photograph, studying those two young faces separated by more than a century.

Margaret and Lily.

What had their relationship really been? And why had this single image survived for 136 years, carefully preserved through generations, she had a growing certainty that this photograph held secrets that desperately needed to be brought into the light.

Marcus Chen arrived with the efficiency of someone who had worked with Elena on dozens of historical investigations.

He carried his laptop, a portable digital microscope, and a color-c calibrated monitor, tools that allowed them to examine historical photographs at magnifications impossible when the images were originally created.

“What have we got?” he asked, setting up his equipment on Elena’s desk.

Elena handed him the photograph in the donation letter.

1888, Savannah, Georgia.

Two girls posed together in what appears to be a friendship portrait.

Tell me what strikes you as unusual.

Marcus studied the image for a long moment, his expression shifting from curiosity to focused intensity.

He had the trained eye of someone who had spent 20 years analyzing historical photographs for evidence of social relationships, power dynamics, and hidden narratives.

“Everything about this is unusual,” he said finally.

Integrated photography from the postreonstruction south, showing black and white children posed as social equals.

That’s not just rare, it’s almost unheard of.

By 1888, the brief promise of reconstruction had been completely crushed.

The South was rebuilding its racial hierarchy through Jim Crow laws, segregation, and systematic violence.

White families didn’t commission expensive photographs, showing their children posed intimately with black children unless there was a very specific message being communicated.

“What kind of message?” Ellen asked, though she was already forming her own hypothesis.

dominance disguised as benevolence.

Marcus said in the 1880s and 90s there was a widespread effort among white southerners to romanticize the antibbellum period.

What historians call the lost cause mythology.

Part of that mythology involved portraying slavery as a benevolent institution where enslaved people were happy, loyal, and treated as part of the family.

White families sometimes commissioned photographs showing their children with black children as a way of demonstrating their supposed kindness and the supposedly natural racial order.

He connected his digital microscope to his laptop and positioned the photograph under its lens.

If I’m right, there will be visual evidence in this image that tells a very different story from the one it was meant to project.

Let’s look closely.

The image appeared on the screen, and Marcus began methodically examining different sections.

He started with the overall composition, then moved to specific details: facial expressions, body positioning, clothing, hands.

“Look at the spatial dynamics,” Marcus said, using his cursor to trace invisible lines on the screen.

Margaret is positioned slightly forward, commanding the visual space.

Her body is angled confidently, shoulders back.

She’s meeting the camera’s gaze directly.

Classic confident positioning for someone who feels entitled to be photographed.

He shifted the focus to Lily.

Now look at the differences.

Lily is positioned slightly back and to the side.

Her shoulders are curved inward, protective body language.

Her chin is lowered in what reads as difference.

And most significantly, her eyes.

She’s not looking at the camera.

She’s looking at a point just below and to the left of the lens.

Avoiding direct eye contact, Elena observed.

That could be shyness, but combined with the other body language.

It reads as trained subservience, Marcus finished.

Someone who has been taught not to meet the gaze of white people directly.

That was a common expectation for black people in the South during this period.

Direct eye contact with white people, especially white women and children, could be interpreted as insolence and punished violently.

Marcus zoomed in on the girl’s hands, and Elena leaned closer to the screen.

The difference was striking and undeniable.

Margaret’s hands were pale, smooth, unmarked.

The hands of someone who had never performed manual labor.

But Lily’s hands told an entirely different story.

Even through the sepia tones of the aged photograph, the evidence was clear.

Lily’s hands showed visible calluses, roughened skin, and what appeared to be multiple small scars across her knuckles and palms.

The fingertips appeared slightly flattened and discolored.

“Those are working hands,” Marcus said quietly.

“Hands that have done hard, repetitive labor for years.

Look at the fingertips.

See these small dark spots? Those are needle punctures.

Hundreds of them overlapping.

She was doing fine needle work probably for hours every day.

Elena felt the familiar combination of sadness and determination that came with uncovering difficult historical truths.

So this photograph isn’t documenting friendship.

It’s documenting servitude.

Marcus adjusted the digital microscope’s focus, moving slowly upward from the girls hands to their upper bodies.

Both dresses appeared well constructed, made from quality fabric with careful tailoring.

But as the magnified image on the screen reached Lily’s neckline, Marcus’ hand suddenly froze on the mouse.

“Elena,” he said, his voice tight with controlled emotion.

“I need you to look at this very carefully.

” The collar of Lily’s dress was high and tightly fitted, as was fashionable in the 1880s, designed to cover most of the neck.

But at extreme magnification, with the digital enhancement tools Marcus was employing, something became visible that would have been impossible to see with the naked eye in 1888, or even in 2024 without specialized equipment.

The collar wasn’t sitting flush against Lily’s skin.

There was a tiny gap, barely a millimeter, where the fabric had shifted slightly.

And in that narrow gap, revealed by digital magnification and contrast enhancement, were marks on Lily’s neck, thin horizontal lines, scars, multiple scars running parallel around her neck.

Elena felt her stomach clinch.

She had seen marks like these before in her research, in drawings and descriptions from slavery narratives, in medical documentation from the Civil War period, but she had never seen them captured in a photograph with this clarity.

Collar scars, Marcus said, his professional composure barely masking his emotion.

From prolonged wearing of a metal collar or repeated use of rope restraints around the neck.

These scars are old.

You can see how they’ve healed and faded.

They would have been created years before this photograph was taken, probably when Lily was much younger.

Elena did the math quickly in her head.

The photograph is from 1888.

Lily appears to be about 14 or 15 years old, which means she was born around 1873 or 74, 8 or 9 years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

She was born legally free.

So, how does she have collar scars? Marcus’ expression was grim because the end of slavery on paper didn’t mean the end of slavery in practice.

In remote areas of the South, some enslaved people weren’t informed of their freedom for months or even years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

Some enslavers simply refused to acknowledge it.

And even when slavery officially ended, it was often replaced by other forms of forced labor.

Convict leasing, debt penage, and voluntary apprenticeship.

Black children, especially orphans or children of extremely poor families, were routinely bound into labor arrangements that were slavery in everything but name.

He enhanced the contrast further and more details emerged.

There were at least four distinct scar lines visible, each one suggesting repeated trauma in the same location.

The skin had healed, but the collagen had formed raised bands.

evidence that these weren’t superficial injuries, but deep repeated abrasions.

The collar would have been worn for extended periods, Marcus continued, his voice clinical now as he shifted into analytical mode.

Maybe as punishment, maybe as a constant restraint.

The scarring pattern suggests it was tight enough to restrict movement.

It caused chafing, probably made of iron or thick rope.

This was sustained deliberate physical restraint of a child.

Ellena stood up, needing to move to process what they were seeing.

We need to examine every detail of this photograph.

If there are collar scars visible, there may be other evidence we haven’t found yet.

Marcus nodded and began systematically scanning other parts of the image at maximum magnification.

He moved to Lily’s wrists where her long sleeves ended just above her hands.

Here, he said, adjusting the contrast again.

Look at her wrists.

Even partially obscured by the sleeve cuffs, additional scarring was visible.

Thin lines circling both wrists.

The same pattern as the neck scars, but less severe.

A wrist restraints.

Elena said she was bound by the wrists as well.

Frequently based on the scarring pattern, Marcus confirmed this wasn’t occasional restraint.

This was systematic, repeated over an extended period during her developmental years.

They continued their examination in silence, documenting each finding with screenshots and detailed notes.

This photograph, which had appeared at first glance to be an unusual but perhaps innocent portrait, was revealing itself to be something far more sinister.

a documented record of child abuse and illegal bondage carefully staged to look like benevolent interracial harmony.

“We need to find out who these girls were,” Elena said finally.

“Their full names, their families, what happened to them after this photograph was taken.

” Lily’s story needs to be told, and the truth about this image needs to be documented and preserved.

Elena returned to her desk and picked up the phone, dialing the number Patricia Whitmore had included with her donation.

The phone rang three times before a woman’s voice answered.

Elderly, but clear and strong.

Hello, Miss Whitmore.

This is Dr.

Elena Rodriguez from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture.

I’m calling about the photograph you sent us.

Oh, there was unmistakable relief in Patricia’s voice.

Yes, I’ve been hoping you would call.

I’ve thought about that photograph constantly since I sent it.

Did you discover something? Elena chose her words carefully.

We did discover something, Miss Whitmore.

Something very significant.

Before I explain what we found, can you tell me more about how you came to possess this photograph and anything you know about the people in it? Patricia took a breath and Elena could hear papers rustling in the background.

I found it last year while clearing out my grandmother Elellaner’s house after she passed away.

She was 97 years old.

The photograph was in an old trunk in the attic along with some letters and other papers.

My grandmother never mentioned it to me while she was alive and I had never seen it before that day.

What was your grandmother’s full maiden name? Eleanor Whitmore.

She was born Elellanena Petan in 1923, but she married into the Whitmore family.

The Whites have been in Savannah since before the Civil War.

They were, Patricia paused, and Elellena could hear the difficulty in her voice.

They were a wealthy family, plantation owners.

I won’t pretend otherwise.

Thank you for being direct, Elena said.

That kind of honesty is crucial for this kind of historical research.

Do you believe one of the girls in the photograph is your ancestor? Yes, I think the white girl, Margaret, might be my great great-grandmother.

There are several Margarets in our family tree around that time period, and the approximate age would be right.

That’s partly why I sent the photograph to you.

I was hoping you could help identify her specifically and perhaps learn about the other girl as well.

The black girl, Lily.

Yes, Lily.

Patricia’s voice became quieter.

Dr.

Rodriguez.

When I first found that photograph, I thought it was touching.

Two young friends from a different era.

But the more I looked at it, the more something felt deeply wrong.

I couldn’t articulate what exactly, but it troubled me.

That’s why I sent it to your museum rather than keeping it or donating it to a local historical society.

I felt it needed to be examined by experts who could understand its full context.

Elena appreciated Patricia’s instinct.

Your intuition was correct, Miss Whitmore.

This photograph does tell a troubling story, but not the story it was intended to tell.

Our analysis has revealed details that weren’t visible to the naked eye when the photograph was taken.

Details that document something very serious.

“What did you find?” Patricia asked, her voice steady despite obvious apprehension.

evidence that Lily was not Margaret’s friend or companion, but rather a servant, possibly held in a condition of forced labor that amounted to slavery, even though this photograph was taken 23 years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

There was a long silence on the line.

When Patricia spoke again, her voice was thick with emotion.

“I suspected something like that, but I hoped I was wrong.

” “What kind of evidence?” “Scarring,” Elena said gently, visible at high magnification around Lily’s neck and wrists, consistent with prolonged use of metal collars and restraints.

the kind of injuries that would have been inflicted on an enslaved or forcibly bound person.

Patricia made a small sound, almost a gasp.

Dear God and my family, Mimu, we don’t know the full story yet, Elena said quickly.

That’s why I’m calling.

You mentioned there were letters in the trunk with the photograph.

Would you be willing to share those with us? They might provide crucial context for understanding what happened to these girls.

Of course, Patricia said immediately.

I saved everything from that trunk.

Some of the letters are faded and difficult to read, but I’ll scan them all and send them to you today.

Dr.

Rodriguez, I want you to know whatever the truth is about my family’s involvement in this, I want it documented.

My grandmother used to say that you can’t heal what you won’t acknowledge.

If my ancestors hurt this child, that truth needs to be known.

Elena felt a surge of respect for Patricia’s courage.

Thank you, Miss Whitmore.

That kind of willingness to face difficult truths is rare and valuable.

I’ll send you my email address, and we’ll begin examining the letters as soon as they arrive.

By late afternoon, Patricia’s email arrived with seven attached scanned documents.

Elellanena and Marcus printed each one and spread them across the large conference table in Elena’s office, arranging them chronologically by the dates written at the top of each letter.

The earliest letter was dated March 12th, 1888, 3 months before the photograph was taken.

Dearest cousin Anne, I write with news from Savannah.

Father has agreed to commission a formal photograph of Margaret with the girl Lily.

He believes the portrait will serve as useful documentation of our family’s Christian charity and the natural affection that exists between the races when proper hierarchy is maintained.

Margaret is quite excited about the prospect as she’s been asking to have her portrait made for some time.

Lily, of course, shows little emotion, as is her nature.

The photographer, Mr.

Harrison, will come to the house in June.

I shall write again with news of how the sitting progresses.

Your devoted cousin, Katherine Whitmore.

Ellena read the letter twice, her jaw tightening.

Christian charity, natural hierarchy.

They’re literally documenting their own propaganda.

Marcus was already examining the second letter.

Dated April 3rd, 1888.

Dearest Dan, regarding your inquiry about the girl Lily, she came to us four years ago when she was approximately 10 years old.

Her mother had been in our family’s service since before the war, but died of fever in 1883.

The girl had no other family, and under the apprenticeship laws, father was able to secure her binding to our household until she reaches the age of 18.

She has proven quite useful in the household, particularly with needle work and attending to Margaret.

Margaret has developed a fondness for her, which father believes demonstrates the beneficial nature of proper racial relations.

The photograph will show how well Lily is treated under our care.

Your cousin Catherine.

Apprenticeship laws, Elena said, anger rising in her voice.

That was one of the loopholes used to continue enslaving black children after emancipation.

Orphaned children or children of poor families were apprenticed to white families supposedly to learn a trade, but in reality it was forced labor with no pay and no freedom to leave.

Marcus had moved to the third letter dated May 20th, 1888.

His face had gone pale.

Elena, you need to read this one.

Oh, the handwriting was different, shakier, less refined than Catherine’s elegant script.

To whoever finds this, my name is Lily.

I’m writing this in secret.

I do not know if anyone will ever read these words, but I must try to leave some record of the truth.

I am not an apprentice.

I’m a slave in all but name.

Mrs.

Whitmore beats me when I am slow with my work.

Mr.

Whitmore put the iron collar on me when I was younger, when I tried to run away.

They took it off two years ago because the marks were too visible, but they said they would put it back if I ever disobeyed again.

Margaret is kind to me sometimes, but she does not understand that I am not her friend.

I am her property.

They’re making me pose for a photograph to show how well they treat me.

I do not know what will become of me, but I’m not happy.

I am not treated well.

If someone reads this, please know that I wanted to be free.

Lily, May 1888.

The room fell silent.

Ellena felt tears burning in her eyes.

This wasn’t just a historical document anymore.

This was a desperate message from a child hidden for 136 years, finally reaching someone who could hear it.

She hid her own testimony, Marcus said quietly.

She knew the photograph would lie about her life, so she wrote the truth and hid it, hoping someday someone would find it and know what really happened to her.

Huh.

Elena carefully photographed the letter with her highresolution camera, documenting every word.

This changes everything.

This isn’t just physical evidence of abuse.

This is Lily’s own voice testifying to what was done to her.

We have her words.

She turned to the remaining letters, her hands trembling slightly.

There were four more documents to exam.

The fourth letter was from Catherine again, dated June 15th, 1888, 9 days after the photograph was taken.

Dearest Anne, the photograph sitting went splendidly.

Mr.

Harrison was most professional, and he understood exactly the image we wished to create.

Margaret and Lily stood together most naturally, and the resulting portrait demonstrates precisely what father intended, the harmony that exists when Christian families provide proper guidance to the negro race.

Lily wore one of Margaret’s older dresses, which we had altered to fit her.

She looked quite presentable.

The photograph will be ready in one week.

Your cousin, Catherine? Elellanena felt disgust rising in her throat.

Margaret’s old dress, altered to fit.

They dressed Lily in handme-downs and called it Charity.

Marcus had picked up the fifth letter, his expression growing darker as he read, “This one was dated July 1888, and written in the same shaky hand as Lily’s hidden testimony.

I’m writing again because I do not know how much more time I have.

They have ordered me not to speak of the photograph or what it shows.

Mrs.

Whitmore said, “If I tell anyone the truth about how I’m treated, they will send me to the workhouse where conditions are worse than death.

” Margaret does not know I wrote the first letter.

She thinks I’m happy to be photographed with her.

She does not understand that I had no choice, that I can never say no to anything this family demands.

Yesterday, she showed me the finished photograph and said we looked like sisters.

I wanted to scream, “We are not sisters.

A sister has freedom.

I’m writing this and hiding it in the same place as my first letter behind the loose board in the attic where they send me to sleep.

If anyone finds these words, please tell my story.

Please say that I existed and that I did not accept this life.

Lily Ellena stood and walked to the window trying to control the emotion welling up inside her.

As a historian, she had read countless documents describing the horrors of slavery in its aftermath.

But there was something uniquely powerful about reading the direct unmediated voice of a child trapped in that system, desperately trying to leave evidence of her own humanity.

“Two more letters,” Marcus said gently.

“Do you want to take a break?” “No,” Elena said, turning back to the table.

“No, we owe it to Lily to read every word.

” She wanted someone to know.

We’re finally the people who can know.

The sixth letter was from Catherine, dated August 1888.

“Dearest Anne, I write with unfortunate news.

The girl Lily has become increasingly difficult in recent weeks.

She has been slow with her work, occasionally impudent in her manner, and yesterday Margaret found her attempting to write something, though she claimed it was nothing but practice at forming letters.

Father has decided that she needs correction.

She will be sent to work in the fields at father’s remaining property outside the city for one month to remind her of her place and her obligations.

Margaret is distressed by this as she has grown accustomed to Lily’s attendance, but father says it is necessary for proper discipline.

The photograph at least remains a beautiful testament to our family’s benevolence.

We have had several copies made.

Your cousin Catherine.

They found her writing the letters, Marcus said.

Or at least they suspected she was writing something.

So they punished her by sending her to do field labor.

Elellena felt a cold rage settling in her chest.

In August in Georgia, field labor in the hottest month of the year for a 14-year-old girl whose hands already showed evidence of years of domestic labor.

The seventh and final letter was in Lily’s handwriting, but it was barely legible.

The letters were shaky and uneven, clearly written by someone in great distress.

This is the last time I will write.

They sent me to the fields for a month.

I’m back now, but I am not well.

My hands are burned from the sun and cut from the cotton plants.

I cannot feel my fingers properly.

Mrs.

Whitmore says, “If I am found writing again, I will be sold away to someone much worse.

” I do not think I can survive being sold.

I’m hiding this final letter with the others.

To anyone who reads this, I was 14 years old.

My mother’s name was Sarah.

She died when I was 10.

I had no choice in coming to this family.

Everything they say about me, everything shown in that photograph is a lie.

I wanted to be free.

I wanted to learn to read more than just simple words.

I wanted to have my own life.

If I do not survive this place, please remember that I wanted these things.

Please remember that I tried to tell the truth.

Lily, September 1888.

The letter ended there, the final words trailing off as if Lily had been interrupted or had lost the strength to continue.

Ellena and Marcus sat in silence for a long moment, the weight of Lily’s words hanging in the air between them.

We need to find out what happened to her.

Elena said finally.

Well, we have her testimony.

We have the photographic evidence of her abuse.

We have the Whitmore family’s own letters documenting how they used her.

But we don’t know if she survived, if she ever escaped, if she lived to see freedom.

Marcus was already opening his laptop.

Savannah has extensive historical records, census data, death certificates, church records.

If Lily lived past 1888, there should be some trace of her.

For the next 3 days, Elena and Marcus worked with obsessive focus, searching through every available historical database.

archive and record collection related to Savannah between 1888 and 1910.

They contacted local historians, genealogologists, and archivists at the Georgia Historical Society.

They examined census records, death certificates, marriage licenses, church registries, and property records.

The Whitmore family was easy to trace.

Wealthy white families kept extensive records and were prominently documented in local newspapers and society registries.

Margaret Whitmore appeared in the 1890 census as a 16-year-old living with her parents.

In 1892, a brief society notice announced her engagement to Thomas Callaway, a Charleston merchant.

She married in 1893 and moved to Charleston, where she lived until her death in 1956 at the age of 84.

She had four children and 14 grandchildren.

Her life was thoroughly documented, privileged, and unremarkable.

But finding any trace of Lily proved far more difficult.

Black domestic workers in the 1880s South rarely appear in official records under their own names, Marcus explained, his frustration evident.

They weren’t listed in census records as separate individuals.

They were just counted as servants in white households.

They didn’t have property to register, and if they died, their deaths often went unrecorded unless there was some legal reason to document it.

Elena refused to give up.

She contacted a genealogologist who specialized in tracing African-American family histories from the post civil war period.

A woman named Dr.

Theresa Washington, who had spent 40 years developing techniques for finding people the historical record had tried to erase.

Dr.

Washington examined the letters, the photograph, and all the documentation Elena had compiled.

Then she went to work with the methodical patience of someone who knew how to read between the lines of incomplete records.

It took her two weeks, but she finally called Elena with news.

“I found her,” Dr.

Washington said, her voice carrying a mix of triumph and sadness.

Or rather, I found what happened to her.

It wasn’t easy, and the trail is fragmentaryary, but I’m confident I’ve reconstructed at least part of Lily’s story after that last letter in September 1888.

I’ll end up with the phone on speaker so Marcus could hear.

Please tell us everything you found.

First, the census records.

In the 1890 census, there’s no Lily listed in the Whitmore household, but that’s not surprising.

They might have hidden her, or she might have been working elsewhere by then.

However, I found a death certificate from October 1888.

A 14-year-old black girl identified only as Lily Ward of G.

Whitmore died at Candler Hospital in Savannah.

Cause of death listed as fever.

Elena felt her stomach drop.

She died 2 months after writing that final letter.

She was 14 years old.

That’s the official record, Dr.

Washington said carefully.

But I also found something else.

A very brief notice in a blackowned newspaper called the Savannah Tribune from November 1888.

It’s just three lines, but it tells a different story.

I’m going to read it exactly as written.

The girl Lily, held by the Whitmore family under false apprenticeship, died last month.

Those who knew her say she was beaten shortly before her death.

The authorities have not investigated.

Justice has not been served.

The room was silent except for the hum of the air conditioning and the distant sound of traffic outside.

“They killed her,” Elellanena said quietly.

“They beat her and she died from her injuries, and the official record says fever, so no one would investigate.

And she was buried in an unmarked grave somewhere with no family to mourn her.

No justice, nothing.

” “There’s one more thing,” Dr.

Washington said gently.

I found a record of a woman named Sarah who worked for the Whitmore family until her death in 1883, listed as a domestic servant.

That has to be Lily’s mother.

The Sarah she mentioned in her letter.

I checked property records from before the Civil War.

And there’s a record of an enslaved woman named Sarah owned by the Whitmore family in 1858.

She would have been about 45 when she died in 1883.

Elena absorbed this information, building a more complete picture.

So Sarah was enslaved by the Whit Moors before the Civil War.

After emancipation, she stayed with them, probably because she had nowhere else to go, no resources, no choice.

When she died, they took her 10-year-old daughter and essentially reinsslaved her through the apprenticeship system.

That’s consistent with everything we know, Dr.

Washington confirmed.

And when Lily tried to resist, when she tried to document the truth about her condition, they punished her so severely that she died from it.

Then they covered it up with a vague death certificate and buried her without ceremony or record.

Ellena spent the next two weeks meticulously documenting everything they had discovered, building a comprehensive case file that told Lily’s story as completely as the fragmentaryary historical record allowed.

She worked with Marcus to create a detailed report that included the original 1888 photograph with extensive digital analysis showing the collar scars, wrist restraints, the calloused hands, and every other physical evidence of abuse and forced labor.

high resolution scans of all seven letters, both the Whitmore family’s correspondence and Lily’s hidden testimony, census records, death certificates, and property documents tracing both the Whitmore family and the enslaved woman Sarah, who had been Lily’s mother.

Historical context about apprenticeship laws and how they were used in the post reconstruction south to effectively continue enslaving black children.

The brief newspaper notice from the Savannah Tribune documenting Lily’s death and the suspicion of violence.

expert analysis from medical historians about the scarring patterns visible in the photograph and what they indicated about the type and duration of restraints used comparative analysis with other documented cases of forced child labor and illegal bondage in the 1880s south.

When the report was complete, Ellena scheduled a press conference at the Smithsonian.

She invited historians, journalists, descendants of both enslaved people and enslavers and representatives from civil rights organizations.

She also personally called Patricia Whitmore and asked if she would be willing to attend.

I’ll be there,” Patricia said without hesitation.

“This is my family’s history, and I won’t hide from it.

” The press conference took place on a cold November morning.

The main hall was crowded with reporters, academics, and members of the public who had heard about the discovery.

Alena stood at the podium with the enlarged 1888 photograph displayed on a screen behind her.

Today, we are presenting the documented story of a child named Lily who lived and died in Savannah, Georgia in 1888.

Ellena began.

While what you see behind me is a photograph that was intended to be propaganda, an image meant to demonstrate the supposed benevolence of a white family toward a black child in their care.

But through modern forensic analysis and the discovery of hidden letters, we can now reveal the truth.

This photograph was designed to conceal.

She walked the audience through each element of the discovery.

The initial analysis of the photograph, the revelation of the scars, the finding of Lily’s letters, the documentation of her death.

As she spoke, the screen behind her displayed highresolution images of every piece of evidence.

Lily was not an apprentice learning a trade, Helena continued, her voice steady and clear.

Ah, she was a child held in forced labor, physically restrained with metal collars and rope, beaten when she resisted, and ultimately killed when she tried to document the truth of her condition.

This photograph, which her captors intended as proof of their kindness, has become instead eternal testimony to her suffering and her resistance.

She paused, letting the weight of those words settle over the room.

But this is also a story about voice and agency.

Lily knew the photograph was a lie, so she wrote her own account and hid it, hoping that someday someone would find it and tell the truth.

Today, 136 years later, we are finally able to do what she asked.

We are telling her story.

We are bearing witness to her life and her death.

We are saying her name and acknowledging what was done to her.

Helena looked out at the crowded room.

Lily died at 14 years old.

We don’t know her full name.

The Whitmore never recorded it, and she had no opportunity to leave more than the few letters we found.

But we know she lived.

We know she resisted.

We know she wanted to be free.

And we know that the photograph we see behind us, which appears to show friendship, actually documents a crime, child abuse, false imprisonment, and ultimately murder.

Patricia Whitmore stood from her seat in the audience.

Elellena had offered her a chance to speak, and she had accepted.

Patricia walked slowly to the podium, her posture straight despite her age.

She looked out at the assembled crowd, then turned to look at the enlarged photograph behind her at her ancestor Margaret standing beside Lily, the lie captured in sepia tones.

My name is Patricia Whitmore, she began, her voice carrying clearly through the microphone.

Margaret Whitmore, the white girl in this photograph, was my great great grandmother.

That means the people who held Lily in bondage, who scarred her with metal collars, who beat her and ultimately caused her death, were my direct ancestors.

The room was absolutely silent.

I could stand here and tell you that I’m shocked, that I had no idea my family was capable of such cruelty, Patricia continued.

But that would be a lie.

I grew up in the South.

I grew up hearing stories about the gracious antibbellum period, about the loyal servants who were part of the family.

Quote, I grew up with euphemisms and silences, with stories that left out the violence and the theft and the horror that made my family’s wealth and comfort possible.

She paused, gathering her thoughts.

When I found this photograph in my grandmother’s attic, something about it disturbed me immediately.

I couldn’t articulate what.

I didn’t have the expertise that Dr.

Rodriguez and Dr.

Chen brought to analyzing it, but I felt the wrongness of it.

And instead of ignoring that feeling, instead of putting the photograph back in the trunk and pretending I’d never seen it, I made the choice to seek the truth.

Patricia turned again to look at the photograph.

The truth is terrible.

My ancestor Margaret lived a long, privileged, comfortable life.

She died at 84, surrounded by family.

Meanwhile, Lily died at 14, alone after years of abuse, her death covered up, and her body disposed of in an unmarked grave.

“That is the truth of what my family participated in.

” She turned back to the audience.

“But I believe we have an obligation to face these truths, no matter how painful.

Because when we refuse to acknowledge what our ancestors did, when we hide behind euphemisms and lost cause mythology and stories about kindness and loyalty, we allow those injustices to continue echoing through generations.

We allow the lies to persist.

” Patricia’s voice grew stronger.

Lily deserves better than that.

She deserves to be remembered truthfully.

She deserves to have her voice heard.

She wrote those letters knowing she might die, hoping that someday someone would read them and know what happened to her.

I’m standing here today to say, “I hear you, Lily.

Your testimony has reached us.

What was done to you was evil, and it was done by people whose blood runs in my veins.

” She paused, visibly emotional.

I’m grateful to Dr.

Rodriguez for uncovering this story.

I am grateful that Lily’s voice has finally been heard and I commit myself to ensuring that her story, the true story, not the lie my family tried to tell through this photograph, is taught and remembered.

That is the only justice I can offer her now across 136 years.

But I offer it completely and without reservation.

Patricia stepped back from the podium to absolute silence, then to prolonged applause.

Ellena embraced her briefly, then returned to the microphone.

What happened to Lily was not an isolated incident, Elena said.

Across the South, in the decades following the Civil War, thousands of black children were forced into apprenticeships and other forms of bondage that were slavery in all but name.

Most of their stories were never documented.

Most of their names were never recorded.

Most of them left no testimony behind, she gestured to the photograph.

But Lily did.

Against enormous odds, knowing the risk she was taking, she wrote down the truth and hid it.

And because of her courage and because of Patricia Whitmore’s courage in seeking the truth about her own family’s past, we now have this complete documented case that we can use to educate people about what really happened during this period.

Ellena looked directly at the cameras recording the press conference.

This photograph will now be permanently displayed in the museum along with Lily’s letters and the complete documentation of her story.

We are also establishing a research initiative to find and document other cases of children held in forced labor after the Emancipation Proclamation.

Lily’s story is one case.

There were thousands of others.

We owe it to all of them to tell the truth.

Three months after the press conference, the Smithsonian opened a new permanent exhibit titled Hidden Voices: The Truth Behind the Photograph.

The centerpiece was the 1888 image of Margaret and Lily displayed alongside the highresolution analysis showing the scars, the collar marks, the evidence of forced labor that had been invisible for 136 years.

But the exhibit didn’t end with the photograph.

On the wall surrounding it were Lily’s letters enlarged so visitors could read her own words.

There were historical documents explaining the apprenticeship system and other forms of post civil war bondage.

There were comparative photographs and cases, stories of other children like Lily whose experiences had been documented in fragmentaryary ways.

And there was a video installation featuring Patricia Whitmore talking about her journey from finding the photograph to confronting the truth about her family’s history and what it had meant to choose truth over comfortable lies.

Elena stood in the exhibit hall on opening day, watching visitors move slowly through the space, reading Lily’s words, examining the photograph, absorbing the weight of the story.

Many people were crying.

Some stood in front of Lily’s letters for long minutes, reading and rereading her testimony.

A young black woman, perhaps 20 years old, approached Ellena.

Thank you for doing this, she said quietly.

Thank you for making sure Lily’s voice was heard.

My ancestors, I don’t know their names.

I don’t have letters from them, but I know their experiences were probably similar to Lily’s.

Seeing her story told, seeing her testimony preserved, it feels like you’re honoring all of them.

Elena felt her throat tightened with emotion.

“That’s exactly what we hoped this exhibit would do.

” Lily’s story is specific and individual, but it’s also representative of thousands of experiences that were never documented.

The young woman nodded, wiping her eyes.

The part that gets me is that she knew.

She knew they were lying about her, and she made sure to leave the truth behind.

She fought back with the only weapon she had.

Her words, that’s powerful.

Throughout the day, similar conversations happened throughout the exhibit hall.

Teachers brought students, families came together, and had difficult conversations about history and truth.

Descendants of enslaved people and descendants of enslavers both came to bear witness.

Late in the afternoon, Patricia Whitmore arrived.

She walked slowly through the exhibit, reading everything, studying the enlarged photograph, standing for a long time in front of Lily’s final letter.

“I come here once a week,” she told Elena.

“To remember, to bear witness, to make sure Lily isn’t forgotten,” she paused.

I’ve been contacted by other descendants of slaveowning families who found your exhibit and want help investigating their own family histories.

They’re ready to face the truth, whatever it might be.

Ellena nodded.

We’re establishing a program to help with exactly that kind of research.

Lily’s case has opened doors.

People are ready to look at these old photographs, these family documents, and ask what really lies beneath the surface.

She turned to look at the photograph of the two girls.

Margaret, who had lived a long, privileged life and died surrounded by family, and Lily, who had died at 14 alone after years of suffering.

But Lily had left her testimony.

And now, 136 years later, people were finally listening.

The photograph that was meant to be propaganda had become testimony.

The lies it was meant to tell, had been exposed, and Lily’s voice, silenced by violence in 1888, was finally being heard.

She wanted someone to remember that she existed, Patricia said softly, echoing Lily’s own words from her final letter.

She wanted someone to know that she fought for her freedom, even if she never achieved it.

And now thousands of people know her story will be taught in schools.

Her words will be preserved forever.

She won.

Elena looked at the photograph one more time at Lily’s carefully neutral expression, her downcast eyes, her scarred hands folded in front of her, and the hidden marks around her neck that modern technology had finally revealed.

Yes, Elena said quietly.

She won.

The truth survived, and we’re making sure it’s never buried again.

The exhibit remained open, telling Lily’s story to new visitors every day.

Her letters were digitized and shared with researchers and educators around the world.

The photograph that was meant to hide the truth had instead preserved it, waiting for the moment when technology and human courage would combined to bring Lily’s voice out of silence and into history.

Margaret Whitmore’s name appeared in census records, birth certificates, society pages, and obituaries.

the full documentation of a life lived with privilege and comfort.

Lily had no last name in any official record, no birth certificate, no proper death certificate, no marked grave, but she had her words.

And now finally she had witnesses.

News

Maria Shriver BREAKS Silence on Tatiana Schlossberg’s Shocking Terminal Cancer Diagnosis 😱💔 Maria Shriver, the beloved Kennedy matriarch, has finally broken her silence on the heartbreaking news that her niece, Tatiana Schlossberg, is battling a terminal cancer diagnosis. But the truth behind her announcement is far more than just a family’s grief—it’s a tale of secrets, betrayal, and untold struggles.

As Maria reveals the devastating news, she hints at dark family tensions that no one saw coming.

What is really happening behind closed doors? 👇

A Shattering Revelation: The Untold Story of Tatiana Schlossberg In the heart of New York City, Tatiana Schlossberg stood at…

Kennedy Family’s Dark Secrets Revealed as Tatiana Schlossberg’s Private Funeral Takes an Unexpected Turn 💔💀 The Kennedy family has always been the epitome of elegance and power, but at Tatiana Schlossberg’s private funeral, the cracks in their façade became glaringly obvious. Behind the closed doors of the somber gathering, a shocking revelation left everyone questioning what really happened to the once-glorious legacy of America’s most famous family.

As whispered voices filled the air and family members exchanged nervous glances, what was meant to be a mournful goodbye turned into a scandalous spectacle.

👇

Shadows of Legacy In the heart of New York City, beneath the weight of a somber sky, the air was…

Tatiana Kennedy: When Doctors Name a Rare Disease, the Media Begins to Ask Painful Questions 💔🔍 When doctors identified a rare disease affecting Tatiana Kennedy, the media quickly turned its focus to her condition, raising painful questions that many weren’t ready to answer. What does this diagnosis mean for her future, and how are the pressures of public life adding to the already overwhelming burden of health struggles? As the story unfolds, the media’s relentless pursuit of answers begins to clash with the private pain of a family already dealing with too much.

What lies beneath the surface of this painful diagnosis? 👇

When a Diagnosis Becomes a Headline and Privacy Begins to Fracture When doctors finally named the rare disease affecting Tatiana…

Tatiana Kennedy: Two Young Children, An Uncertain Future, and Decisions Made When Their Mother No Longer Speaks Up 💔👶 Tatiana Kennedy’s story is not just one of fame and legacy, but of two young children left to navigate an uncertain future without their mother’s voice guiding them. With every decision made in silence, the heavy weight of a family’s burden falls on the shoulders of those left behind.

What choices will be made for these children’s futures? And how does the absence of their mother’s influence shape the path they must now take? The decisions ahead could change everything.

👇

When the Quiet Decisions Begin and a Mother’s Voice Is No Longer There The story of Tatiana Kennedy does not…

Tatiana Schlossberg – The Youngest Granddaughter of the Late President John F. Kennedy: Just a Medical Tragedy, or a Series of Pressures Pushing a Person to Their Breaking Point? 💔🔍 The death of Tatiana Schlossberg, the youngest granddaughter of the late President John F.

Kennedy, is not only a medical tragedy but also a story filled with tension, pressure, and untold secrets.

Could the struggles in her family life and the pressure of fame be the real reasons behind her tragic end, or is there a deeper, unexplored factor at play? What unexpected details might reveal the truth about her life? What lies behind this tragedy? 👇

The Weight of a Famous Name and the Quiet Collapse Beneath It The story of Tatiana Schlossberg, the youngest granddaughter…

Tatiana Schlossberg’s Private Funeral: Caroline Kennedy’s Tribute Will Leave You in Tears 💔😭 The private funeral for Tatiana Schlossberg, daughter of Caroline Kennedy, was a deeply emotional event that moved everyone in attendance. Caroline’s heartfelt tribute to her beloved daughter brought the room to tears, revealing the deep bond between mother and child.

What Caroline said about Tatiana’s legacy, love, and spirit will haunt you long after the service ends.

Get ready for a deeply emotional, raw tribute to a life cut too short.

👇

The Final Curtain: A Tribute to Shadows In the dim light of a private chapel, the air was thick with…

End of content

No more pages to load