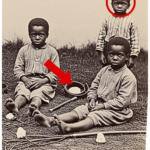

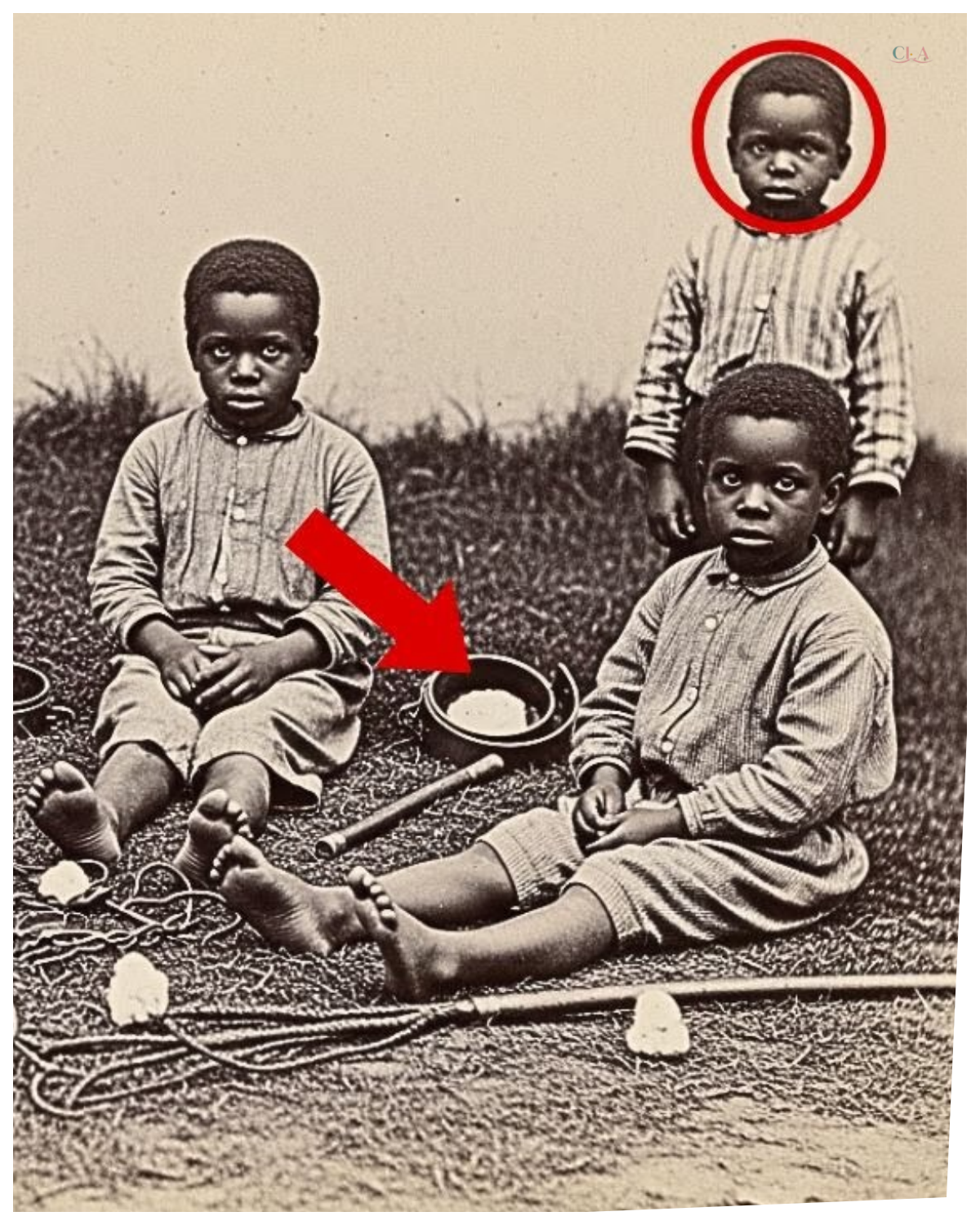

This Photo Seemed to Show Children at Play — Until Experts Saw What Was on the Ground

This photo seemed to show children at play until experts saw what was on the ground.

Dr.James Carter carefully unfolded the protective acid-free paper surrounding the newly acquired photograph in the archives of the National Museum of African-American History in Washington DC, the sepiaoned image dated 1858 showed five children on what appeared to be the grounds of a southern plantation.

At first glance, they seemed to be arranged in a playful circle, their postures suggesting a moment of childhood joy captured by an early photographer.

Another misleading propaganda piece,” James murmured, familiar with how plantation owners commissioned photographs portraying slavery as benign.

He was about to file it when something caught his trained eye.

“Helen, could you bring me the magnifier?” he called to his assistant.

Under magnification, what he saw made his stomach tighten.

On the ground around the children’s bare feet weren’t toys, as the composition suggested, but tiny shackles partially buried in dirt, a small whip disguised as a stick, and what appeared to be cotton picking tools.

Most disturbing was a metal collar half hidden in the grass behind the smallest child.

A boy no older than seven.

“My God,” Helen whispered, looking over his shoulder.

“They were forced to pose,” James said, his voice tight.

“Look at their eyes.

They’re terrified.

Indeed, beneath the staged smiles, the children’s eyes told a different story, particularly the smallest boy, standing slightly apart, whose gaze held something beyond fear, a quiet defiance.

” James checked the back of the photograph where faded handwriting read, “Fair View Plantation, Georgia, 1858.

Master Williams Amusements.

” Below, barely legible in a different hand.

Thomas, age seven, sold 3 days after.

“I need to find out who Thomas was,” James said, already feeling a connection to the child with defiant eyes.

“This isn’t just another plantation photo.

It’s evidence.

These children were posing under duress, and someone tried to document it secretly.

” Well, what began as routine archiving was about to become something much more significant.

The morning light streamed through the high windows of the research room as James spread out his materials.

The photograph of the five children lay at the center surrounded by plantation records, slave sale documents, and maps of Antabbellum, Georgia.

Fairview Plantation belonged to the Henderson family, Helen said, placing a ledger beside the photo.

William Henderson Jr.

was 19 in 1858.

Likely the master William mentioned.

James nodded, scanning the ledger.

And here, a sale record dated June 18th, 1858.

Boy Thomas, age seven, purchased by Nathaniel Reed of Charleston for 475.

3 days after the photograph’s date.

Why would they photograph children they were about to sell? Helen wondered.

That’s what’s unusual, James replied.

These photographs were expensive.

Plantation owners typically only photographed slaves they considered valuable property or wanted to document for some reason.

James studied the image again.

The four other children seemed resigned, but Thomas’s expression remained anomalous, a look that suggested awareness beyond his years.

Now look at his hands,” James pointed.

“They’re clenched, while the others are open, as instructed.

” A quick search of Reed’s records revealed another surprise.

Unlike most slave purchasers, Reed had kept detailed notes.

“Boy Thomas, literate contrary to indication, discovered reading in the stables one week after purchase.

” James read aloud.

“Punishment administered, value diminished.

” Helen’s eyes widened.

“He could read at 7.

Someone taught him secretly,” James said.

“That was extraordinarily dangerous for both teacher and child.

” Further in Reed’s notes, a troubling entry.

Thomas escaped July 3rd.

Blood hounds dispatched.

A seven-year-old tried to escape, Helen whispered.

James sat back, mind racing.

What happened to this child? Did he survive? And who took this photograph, positioning it to subtly reveal the tools of oppression? The mystery was deepening, and James felt increasingly drawn to uncover the story of the small boy with defiant eyes and dangerous knowledge.

James spent three days examining the photograph under different light.

On the third day, using ultraviolet light, faint writing appeared along the bottom edge, nearly invisible to the naked eye.

Remember them.

TWW? He read aloud.

TWW? Could that be our photographer? A search through historical records of photographers working in Georgia during the 1850s, yielded a promising lead.

Thomas Woodson, a free black man who had established a small photography business in Savannah.

This was incredibly dangerous work, James explained to the museum director, Dr.

Amelia Phillip.

If Woodson was secretly documenting the realities of slavery, it would explain why these photographs aren’t in our regular collections, Amelia finished.

They would have been hidden, passed along through underground networks.

Further research revealed Woodson had connections to abolitionists and possibly the Underground Railroad.

A journal entry from a Northern abolitionist mentioned photographs from W that will change hearts if we can circulate them safely.

Meanwhile, Helen traced young Thomas’ journey after his escape attempt.

Reed’s plantation records showed he had been recaptured and severely punished.

But surprisingly, instead of being sold at a lower price, as was common practice with troublesome slaves, he was kept on the plantation.

Listen to this entry from September 1858.

Helen said, “Boy Thomas assigned to kitchen duties under Cook Martha restricted from field work due to continued flight risk.

” “That’s unusual,” James noted.

“Why keep a child they considered a problem?” The answer came in a letter from Reed to a business associate.

Martha claims the boy is her grandson and threatened to poison the household if he was sold as she is the finest cook in Charleston and impossible to replace.

I have acquiesed to her demands for now.

Thomas had family protecting him, James said softly, and possibly connections to Woodson, our photographer.

Oh, mom.

The pieces were beginning to form a more coherent picture, one of resistance, family bonds, and dangerous documentation.

James traveled to Charleston to examine the former Reed Plantation records preserved in the South Carolina Historical Society.

The building that once housed the kitchen still stood on the property, now a historical site.

Martha was highly valued, the site historian explained as they toured the kitchen house.

She had unusual leverage for an enslaved person.

In the plantation’s household accounts, Martha appeared frequently.

Christmas bonus to Martha for exceptional service and special allowance of fabric to Martha for new dress, governor’s dinner.

She used her position strategically, James observed, building goodwill while protecting Thomas.

In a corner of the kitchen house, beneath a loose floorboard identified during a 1970s renovation, conservators had found a small bundle, a child’s reading primer with letters practiced in the margins, a carved wooden figure, and most significantly, a folded paper with crude handwriting.

Thomas learning good, dangerous, but proud.

Martha was teaching him to read, James realized, continuing whatever education he had begun before being sold.

Further research uncovered kitchen records showing Martha had been hired out occasionally to work at functions in Charleston, sometimes with her kitchen boy.

“These trips to the city could have provided opportunities for contact with free black communities and possibly Thomas Woodson.

” “I think Martha and Woodson were collaborating,” James told Helen over their evening call.

She was positioning Thomas to eventually escape, and Woodson was documenting conditions on plantations.

The next morning, James discovered a newspaper clipping from 1861.

“Slave uprising concerns as war approaches.

Notable escape of Cook and Child from Reed Plantation amid chaos.

Reward offered.

They got away, James whispered, feeling an unexpected surge of emotion.

As the civil war began, Martha and Thomas escaped.

The trail grew colder after their escape.

“Where had they gone? Had they reached freedom?” The questions multiplied as James dug deeper into the increasingly compelling story of the boy from the photograph.

In Philadelphia, James met with Dr.

Vanessa Johnson, a leading expert on the Underground Railroad.

Charleston had one of the most sophisticated urban underground railroad networks, she explained, spreading out a map marked with safe houses and roots.

For a skilled cook like Martha with city connections, escape was dangerous but possible.

Vanessa introduced James to a collection of letters written by William Still, a renowned underground railroad conductor.

In one dated December 1861, Still mentioned receiving M and her grandson T recently from Charleston.

Boy shows remarkable literacy and observational skills.

That must be them, James said excitedly.

There’s more, Vanessa said.

Still noted that the boy carried images of importance sewn into his clothing.

Given Woodson’s connection, these could have been photographs.

The trail led to Philadelphia’s vibrant pre-war black community.

City directories listed a Martha working as a cook at an abolitionist household in 1862.

School records from a Quaker run education program for formerly enslaved people included a Thomas, age 11, advanced reader.

He was receiving formal education, James noted.

Martha’s risk-taking paid off.

Most intriguing was a letter from abolitionist Frederick Douglas mentioning a remarkable young man lately from bondage who carries powerful evidence of the conditions in Georgia plantations.

His testimony and photographic evidence have been most persuasive in our overseas appeals.

Thomas was actively involved in abolitionist work.

Vanessa confirmed the photographs weren’t just documentation.

They became tools in the international campaign against American slavery.

As the Civil War raged, records showed Thomas, though still a teenager, working with Union forces, possibly as a messenger or spy, roles where his literacy and knowledge of plantation layouts proved invaluable.

He transformed from a victim to an agent of change, James said.

But the defiance we saw in his eyes in that photograph wasn’t just a momentary expression.

It defined his life’s trajectory.

The story was growing beyond what James had initially imagined.

Not just a documentation of horror, but a narrative of resistance, education, and the fight for freedom.

The Civil Warriors transformed Thomas from child to young man.

Military records from 1864 mentioned a te from Charleston, serving as a guide to Union forces in coastal Georgia.

His intimate knowledge of the region proving invaluable.

He would have been only 13 or 14, Helen noted as she and James reviewed the documents.

“Children grew up quickly in those circumstances,” James replied.

“His unique background made him particularly valuable.

” A report from a Union officer praised the colored youth T, whose intelligence regarding plantation layouts near Savannah significantly aided our advance while minimizing civilian casualties.

Martha’s trail led to a contraband camp in Union controlled territory where she worked as a head cook, feeding both refugees and soldiers.

Camp records noted her as Martha, formerly of Charleston, with skills exceeding most.

As the war ended and reconstruction began, Thomas’ education continued.

An 1866 enrollment record from a Freedman’s Bureau school listed Thomas, age 15, advanced placement, his teacher commented, shows exceptional aptitude for science and writing, assists in teaching younger students.

Most exciting was James’ discovery of a dgeray from 1867, showing a young black man in formal attire, standing confidently beside photographic equipment.

The back bore the inscription, “Studio apprentice Thomas with gratitude, T.

Woodson.

” The connection is confirmed, James said.

Thomas Woodson took him as an apprentice.

Woodson’s diary, preserved in a small collection of black photographers’s papers, mentioned his apprentice.

Young T shows remarkable talent for composition.

His eye for truth comes from bitter experience, yet he creates images of great beauty and dignity.

He went from being the subject of a dehumanizing photograph to creating empowering images himself, Helen observed.

That’s extraordinary.

James nodded.

It’s a powerful transformation, but there’s a gap in our knowledge of his later life.

The historical record grows sparse after 1870.

The challenge now was to track Thomas into adulthood and discover what had become of the boy with defiant eyes who had survived slavery, war, and displacement.

Between 1870 and 1880, Thomas’ trail grew faint.

The most promising lead came from business directories showing T.

Walker photographer operating briefly in Philadelphia, then Boston.

Walker, Helen questioned during their research call.

Many formerly enslaved people chose new surnames after emancipation, James explained.

Walker was common.

It suggested mobility and freedom.

In Boston’s archives, James discovered photography studio advertisements for Walker’s authentic portraits, promising true dignity in every image.

Several surviving photographs bore the studio’s stamp, showing black families posed not as curiosities or anthropological subjects, as was common in that era, but with dignity and individuality.

His approach was revolutionary, James told the Museum Board.

While contemporary white photographers often depicted black Americans as types rather than individuals, Thomas captured the full humanity of his subjects.

Financial records showed the studio struggled initially but gained patronage from Boston’s elite black community and progressive white clients.

By 1880, however, Walker’s authentic portraits disappeared from directories.

The mystery deepened until Helen found a newspaper announcement from Chicago.

New studio opening T.

Walker, photographer of Boston, brings his celebrated approach to Chicago’s growing community.

Chicago city directories confirmed Thomas had relocated, establishing a larger studio that specialized in family portraits and documentary images of modern negro life.

His business expanded through the 1880s, suggesting financial success unusual for a black business owner of that period.

A profile in a local black newspaper described him, “Mr.

Walker, though quiet about his early life, speaks passionately about photography’s power to show truth and create new understanding.

His images of working-class black families have appeared in national publications.

He was using photography as both art and advocacy, James noted, continuing the documentary approach that Woodson began, but reaching a wider audience.

The research revealed Thomas developing from apprentice to innovator, creating a visual language that countered degrading stereotypes with images of black dignity, achievement, and ordinary life, a revolutionary act in postreonstruction America.

In the Chicago Historical Society archives, James discovered devastating news.

Thomas’ studio had been destroyed in a suspicious fire in 1891.

A newspaper report read, “Fire marshall investigating blaze at Negro Photographers Studio.

Owner T.

Walker claims arson following publication of controversial images.

Entire collection lost.

What were these controversial images?” James wondered aloud.

The answer came from an unexpected source, the personal papers of IDB.

Wells, the crusading journalist who documented lynchings across America.

Wells had commissioned Thomas to photograph a lynching site the day after a murder, creating evidence that contradicted official narratives.

Walker’s photographs proved the victim had been tortured before death.

Contrary to newspaper claims of a quick execution, Wells wrote, “His technical skill captured details authorities tried to erase.

Within days of the images limited circulation, Thomas’ studio burned.

” While investigating the fire, James uncovered a pattern.

Thomas had been systematically documenting racial violence and inequality across Chicago, creating a visual record that challenged the prevailing narratives.

Insurance records listed the studios contents.

23 albums of documentary photographs.

Over 100 glass plate negatives.

Personal collection described as historical significance by owner completely destroyed.

A police report noted Thomas had been severely beaten by unknown asalants who warned him to stop making trouble with that camera.

They tried to silence him, James said grimly.

But did they succeed? The answer lay in a letter Thomas wrote to a friend after recovering from his injuries.

They may have destroyed my studio and negatives, but not my resolve.

I have secured new equipment and will continue my work more carefully.

Some images survived.

Those I kept closest.

Thomas’ resilience echoed the defiance James had first noticed in the eyes of that 7-year-old boy in the plantation photograph.

Decades later, he was still fighting now with a camera as his weapon.

Following the fire, Thomas disappeared from public records until James discovered a deed for a small farm outside Chicago purchased in 1892 under the name Thomas W.

Freeman.

Another name change, Helen noted.

Freeman, making his statement even clearer.

Local records showed Thomas living quietly as a farmer, though neighbors accounts mentioned his strange hobby of taking pictures.

He married a school teacher named Ruth, and they had two children.

The breakthrough came when James located Thomas’s granddaughter, Elizabeth Carter, now in her 80s, still living in Illinois.

Grandpa Thomas didn’t talk much about his early life, Elizabeth explained during their meeting.

But he never stopped taking photographs.

Our cellar was his dark room.

Elizabeth led James to her attic where a weathered trunk contained what Thomas had saved from his life’s work, including remarkably the original plantation photograph that had started James’ investigation.

“He kept this all his life?” James asked, stunned.

Elizabeth nodded.

He said it reminded him of where he came from and why his work mattered.

The trunk contained hundreds of photographs spanning decades.

Images of black Americans in everyday life, at work, in celebration, in mourning, a complete visual narrative challenging stereotypical depictions.

Most astonishing was a handwritten memoir titled From Property to Photographer that began, “I was seven years old when a man named Woodson risked his life to show the world what slavery truly meant.

His courage taught me that a camera could be more powerful than a rifle.

” The memoir detailed Thomas’ journey, his early literacy, thanks to Martha’s dangerous teaching, his escape, wartime experiences, and his dedication to capturing truth through images.

He wrote this for future generations, Elizabeth explained.

He always said someday America would be ready to see itself clearly.

James realized he had found not just the resolution to the mystery of the plantation photograph, but an extraordinary historical treasure, a firsthand account spanning from slavery through reconstruction and beyond, told by a man who had transformed himself from a possession to a witness.

6 months later, James stood in the center of the National Museum of African-American History’s newest exhibition, from property to photographer, the extraordinary journey of Thomas Walker Freeman.

The original plantation photograph held the central position, now properly contextualized.

Beside it hung Thomas’ portraits from every stage of his career, showing his evolution as an artist and documentarian.

The exhibition had drawn international attention.

Visitors moved slowly through the gallery, many visibly moved by the power of the images and the story they told.

“What strikes me most,” James said to a group of students, is how Thomas reclaimed the power of photography.

The medium that once documented him as property became his tool for asserting humanity and truth.

Thomas’s memoir, carefully preserved and digitized, had been published to critical acclaim.

His photographs, hidden for decades, now appeared in textbooks and media worldwide.

In the final room, a large screen displayed a rotating selection of Thomas’s images alongside contemporary photographs addressing similar themes, showing how his pioneering work had influenced generations of documentary photographers.

Elizabeth Carter, attending the opening with her children and grandchildren, stood quietly before the plantation photograph where it all began.

He would be amazed to see this, she told James.

Not just his work being recognized, but how the conversation about our history has evolved.

James nodded.

The objects on the ground in that first photograph, the shackles, the whip were meant to be hidden in plain sight.

Thomas spent his life bringing such hidden truths into focus.

As visitors continued to stream into the exhibition, James watched their reactions, the moments of recognition, reflection, and sometimes tears.

What had begun with his noticing small details in a single photograph had uncovered not just one man’s remarkable journey, but a powerful lens through which to view American history.

Through Thomas’s eyes and camera, visitors could trace a path from enslavement to agency, from objectification to artistic expression, revealing a story of resistance and resilience that had nearly been lost to

News

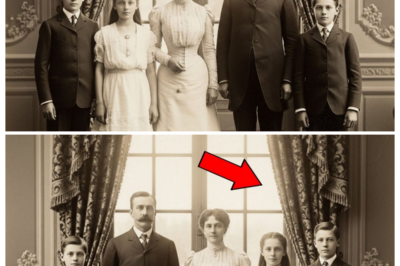

A Family Photo From 1895 Looks Normal — When They Zoom In on the Girl, They Discover Something A family photo from 1895 looks normal. When they zoom in on the girl, they discover something. The humidity in New Orleans made everything stick. Papers to fingertips, shirts to skin. Even the air itself seemed to cling. Dr.Vivien Rouso wiped her forehead and adjusted the desk fan in her cramped office at the Louisiana Historical Archives. August in the city was relentless, but the climate controlled vault where the photographs were stored remained mercifully cool. She had spent three months cataloging the TME collection. Hundreds of photographs, documents, and artifacts from one of America’s oldest African-American neighborhoods. Most items had been donated by families cleaning out atticss and estate sales. Pieces of history saved from dumpsters and obscurity. Vivien opened a mahogany box lined with aged velvet.

A Family Photo From 1895 Looks Normal — When They Zoom In on the Girl, They Discover Something A family…

Corporate Detonation! 💥 California Governor LOSING CONTROL After Chevron’s Explosive Move Sends Shockwaves Through Sacramento and Turns Boardrooms Into War Rooms! What insiders describe as a calculated corporate thunderclap rips through the governor’s carefully staged calm as Chevron’s sudden pivot exposes years of quiet tension, whispered warnings, and regulatory brinkmanship, leaving aides scrambling, critics circling, and Californians wondering how a single move could unravel a narrative so fast that even spin doctors can’t keep up with the fallout 👇

The Fall of a Titan: A California Tragedy In the heart of California, where dreams are born and crushed under…

Fuelgate California! ⛽ Governor Enters Full Damage Control Mode as CARBOB Crisis Slams 40 Million Lives and Turns Everyday Commutes Into a Psychological Endurance Test! What began as a technical fuel specification quietly detonates into a statewide meltdown as motorists feel betrayed, experts whisper about regulatory arrogance, and Sacramento scrambles to spin a narrative fast enough to outrun public fury, with insiders warning this isn’t just about gas but about trust, power, and a leadership style now exposed under fluorescent station lights while the clock ticks toward something worse 👇

The Fuel of Deception In the heart of California, a storm was brewing that would shake the foundations of power….

Dairy Dynasty Defects! 🧀 California Governor Scrambles as Leprino Foods Quietly Packs Up and Flees—And the REAL Fallout Is Far Worse Than Anyone Admits! What looked like a routine corporate relocation suddenly curdles into a political nightmare as insiders whisper about regulatory chokeholds, rising costs, and a breaking point the governor swore would never come, leaving workers stunned, towns anxious, and Sacramento spinning as the exit exposes cracks no press conference can seal 👇

The Last Slice of Hope In the heart of California, where sun-kissed fields stretched endlessly, a storm was brewing. Evelyn,…

California Betrayal Exposed! 🧨 Governor Takes the Blame as Valero CEO Finally Spills the REAL Reason Behind the Energy Shockwave That No One Was Supposed to Hear! In a moment that felt less like an interview and more like a confession, the Valero CEO peeled back the curtain on whispered deals, regulatory pressure, and political ego clashes, leaving the governor scrambling as Californians realize this crisis wasn’t an accident—it was engineered through silence, misdirection, and power plays that turned everyday drivers into collateral damage 👇

The Reckoning: A Tale of Power and Betrayal In the heart of California, where the sun sets over the Pacific,…

End of content

No more pages to load