This forgotten portrait resurfaced 100 years later — and changed history

This forgotten portrait resurfaced 100 years later and changed history.

The autumn rain drummed steadily against the windows of Morrison’s auction house in Boston as Dr.James Parker browsed through boxes of forgotten photographs.

The musty smell of old paper and leather filled the cramped back room where estate sale items waited to be cataloged.

James, a history professor specializing in post Civil War America, had spent countless Saturday mornings in places like this, searching for pieces of the past that textbooks overlooked.

He lifted a stack of tint types and cabinet cards, most showing stern-faced Victorian families whose names had been lost to time.

Then his fingers paused on a particular photograph.

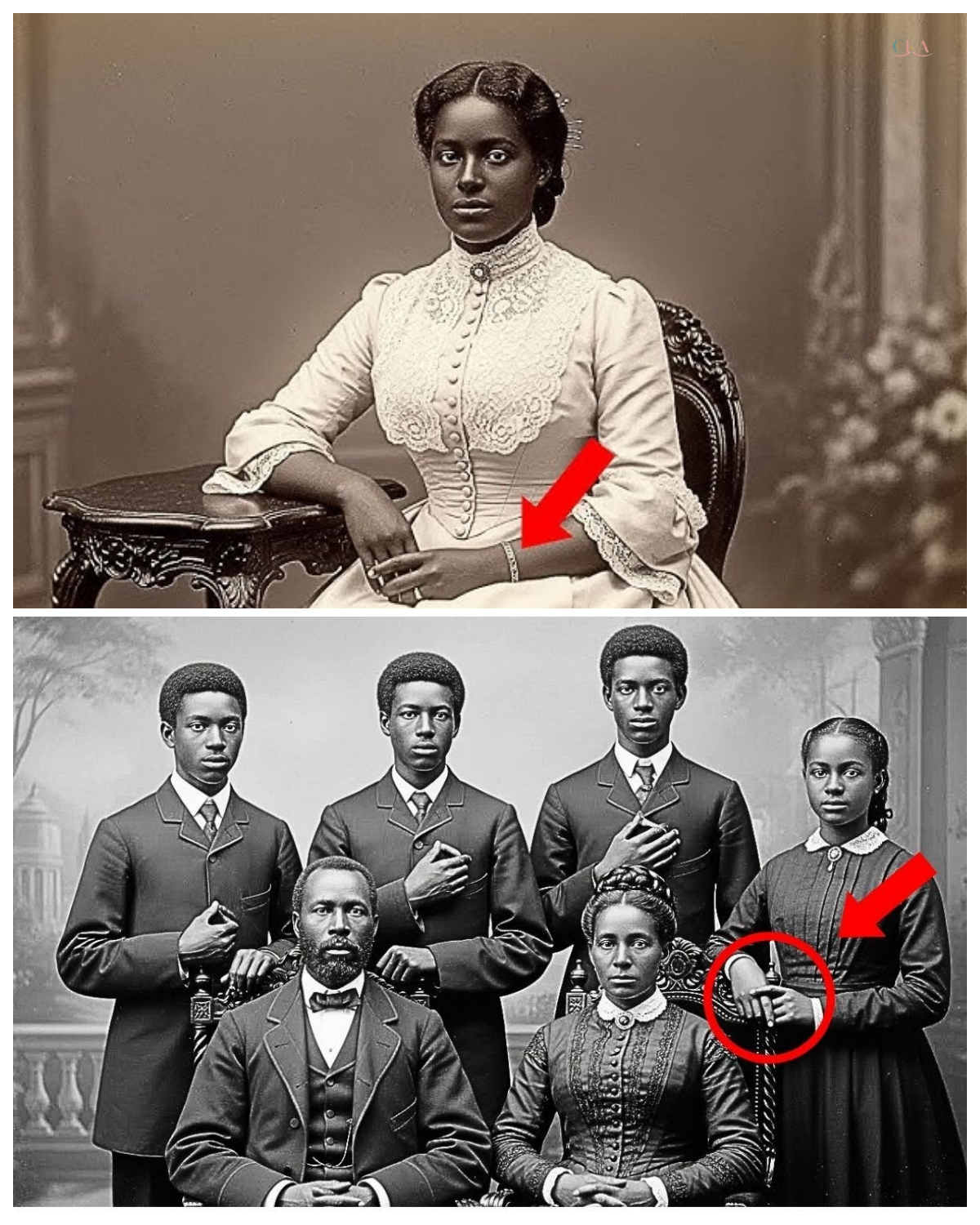

The image showed six African-American individuals posed formally in a studio setting, the kind of portrait that would have cost a working family weeks of wages in 1890.

James held the photograph closer to the dim light.

The family was impeccably dressed.

The patriarch sat centered, his dark suit pressed, a watch chain visible across his vest.

Beside him, a woman in an elegant high-colored dress, gazed at the camera with quiet dignity.

Their children, three young men and a woman, stood behind them.

The painted backdrop depicted classical columns and a pastoral landscape, standard for photography studios of that era.

What struck James immediately was the rarity of the image itself.

Photographs of African-American families from this period were uncommon, often lost or destroyed over generations.

This one had survived in remarkable condition.

The sepia tones still rich, the details crisp.

He turned it over.

On the back, written in faded ink, the Lawrence family, Philadelphia, September 1890.

He was about to set it aside when something made him look again.

Their hands.

Each person’s hands were positioned oddly, not in the relaxed or formally clasped poses typical of Victorian portraiture.

The father’s right hand rested on his knee with three fingers extended and two-folded.

The mother’s hands were crossed at her lap, but her left thumb protruded at an unusual angle.

One son’s hand was placed flat against his chest.

Another held his hands behind his back in a way that seemed unnatural.

James felt his pulse quicken.

In 15 years of studying historical photographs, he had learned to notice details others missed.

These hand positions were too deliberate, too specific to be random.

They meant something.

He carried the photograph to the front desk, where Mrs.

Morrison tallied his items.

“$5 for the lot,” she said, barely glancing at his selections.

James paid quickly, tucking the photograph into his leather satchel.

Outside, the rain had intensified, but he barely noticed.

His mind raced through possibilities, historical contexts, and the question that would consume him.

What were the Lawrence family trying to tell the world? James spread the photograph across his desk at Nor Eastern University Monday morning.

Pale November sunlight filtered through his office window as he positioned his magnifying lamp directly over the image.

He had spent the entire weekend thinking about those hands, unable to shake the feeling that he had stumbled onto something significant.

Through the magnifying glass, every detail became clearer.

The father, who appeared to be in his 50s, had a dignified bearing despite his unusual hand position.

His three extended fingers pointed subtly downward.

The mother’s crossed hands revealed something else under magnification.

Her right index finger touched her left wrist at a precise point, almost like she was checking a pulse, but the gesture was clearly intentional for the photograph.

The eldest son, standing behind his father, had his right hand pressed flat against his chest, fingers spread.

The second son’s hands, clasped behind his back, were partially visible at his sides, and James could see his thumbs were interlocked in an unusual way.

The daughter’s hands rested on her mother’s shoulder, but her pinky fingers were extended while the others were curled.

The youngest son, at the far right, had one hand in his pocket, the other hanging at his side with his palm facing forward.

James pulled out his collection of reference books on Victorian photography.

He had studied thousands of period portraits, and standard poses were well documented.

Photographers of that era gave specific instructions.

Hands folded in lap, resting on a table, holding a book, or placed formally on armrests.

What they did not do was create asymmetrical, seemingly random positions that differed for each person in a group portrait.

He photographed the image with his digital camera and enlarged sections on his computer screen.

The hand positions became even more deliberate at higher magnification.

These were not accidents or moments of movement captured by a slow shutter speed.

Each person had held their position perfectly still for the long exposure time required in 1890, which meant these gestures were intentional and maintained with purpose.

James leaned back in his chair, his mind working through the timeline.

The photograph was dated September 1890.

The Civil War had ended in 1865, and the 13th Amendment abolished slavery that same year.

The Underground Railroad, that secret network of routes and safe houses that helped enslaved people escape to freedom, had effectively ceased operations by the end of the war, 25 years before this photograph was taken.

So why would a family in 1890 be using what appeared to be coded hand signals? James spent the next two weeks buried in research.

He started with the most comprehensive source he could find, a rare collection of Underground Railroad documentation held in the university’s special archives.

The materials included correspondence between abolitionists, coded messages, quilts with symbolic patterns, and most importantly, a small leather journal that had belonged to a conductor named William Still.

Often called the father of the Underground Railroad, Still had meticulously documented the stories of hundreds of people he helped escape to freedom.

But tucked into the journal’s back pages, James found something unexpected.

Sketches of hand signals.

They were crude drawings, but the annotations were clear.

Signal for safe house.

warning of danger, request for food and shelter, indication of number of travelers.

James’ hands trembled as he compared the sketches to his photograph.

The father’s three extended fingers matched a signal that meant three people seeking passage.

The mother’s finger on her wrist corresponded to family connection or blood relation.

The son with his hand on his chest was signing freed person or survivor.

He cross referenced these findings with other sources.

A memoir by Harriet Tubman’s niece mentioned silent speech used when words could bring death.

Uh, a letter from Levi Coffin, a Quaker abolitionist, referenced the language of hands that guided souls to freedom.

These signals had been a crucial communication method when enslaved people and their helpers needed to identify each other without speaking, especially in areas where slave catchers were active.

But James kept returning to the same problem.

Why would the Lawrence family be photographed using these signals in 1890? The need for such secrecy had ended decades earlier.

There were no more escapes to coordinate, no more safe houses to identify, no more slave catchers to evade.

He decided to trace the Lawrence name.

Philadelphia city directories from 1890 listed several Lawrence families, but finding the specific one would require more detail.

He needed to know where they lived, what they did for work, anything that could narrow his search.

James returned to the photograph itself, examining every element.

The studio backdrop caught his attention.

Most photographers used generic painted scenes, but this one had distinctive features.

The columns had unusual capitals, and in the distant background, barely visible, was a painted structure that looked like a specific building.

He began researching Philadelphia Photography Studios Active in 1890, cross-referencing their addresses with known backdrops.

It was painstaking work, but on the third day, he found a match.

The studio belonged to Augustus Washington Jr.

, a black photographer who had established his business on South Street in Philadelphia in 1888.

James discovered that Washington was not just any photographer.

He was the son of Augustus Washington senior, a prominent dgerayotypist who had photographed Frederick Douglas and been active in abolitionist circles before immigrating to Liberia in 1853.

The younger Washington had returned to America in 1885 and opened his studio specifically to serve the African-American community.

In an era when many photographers refused to photograph black clients or charged them exorbitant rates, Washington’s studio became a gathering place and symbol of pride.

James found a brief mention of the studio in a Philadelphia Historical Society newsletter from 1982.

It included an address 412 South Street.

The building no longer existed, replaced by modern development, but the Historical Society had archived some of Washington’s business records, including a ledger of appointments.

James made the 2-hour drive to Philadelphia on a cold December morning.

The Historical Society occupied a converted townhouse in Society Hill, its rooms filled with documents, maps, and artifacts from the city’s past.

A librarian named Dorothy, a black woman in her 60s with reading glasses hanging from a beaded chain, greeted him warmly.

“We don’t get many researchers interested in Augustus Washington Jr.

,” she said, leading him to a climate controlled room.

“His father is better known, but the son did remarkable work documenting the black community in the 1890s.

She placed a leatherbound ledger on the table before him.

James carefully turned the pages, scanning entries from September 1890.

Most were simple, names, dates, prices paid.

Then he found it.

September 14th, 1890.

Lawrence family, six persons.

Special sitting, no charge.

No charge.

That was unusual.

Washington ran a business.

Yet he had photographed this family for free.

The notation special sitting appeared only twice in the entire ledger that year.

Dorothy, James said, looking up, “What would make a sitting special in 1890? And why would a photographer not charge?” Dorothy adjusted her glasses and peered at the entry.

Special sittings were often for important community members or for photographs meant to serve a particular purpose.

As for no charge, that suggests a personal connection or a favor.

In those days, doing something for free meant it mattered deeply to both parties.

James photographed the ledger page, then asked if there were any other Washington materials.

Dorothy disappeared into the back and returned with a wooden box.

Inside the box were loose papers, correspondents, and several dozen glass plate negatives carefully wrapped in cloth.

Dorothy explained that Washington’s studio had closed in 1903 when he died suddenly and his widow had donated these materials to the historical society in 1911.

James carefully examined the letters, most of which were routine business correspondents.

Then he found one that made his breath catch.

It was dated August 30th, 1890, 2 weeks before the Lawrence family photograph written in elegant script on cream colored paper.

Dear Augustus, I write to request your assistance with a matter of great personal importance.

My family wishes to create a permanent record, a testimony that can survive when memories fade.

We have discussed this among ourselves and believe you are the only one we can trust with this task.

The sitting must be private and we ask that you guide us in the old way.

We will come to you in September.

Your friend in freedom, Thomas Lawrence, the old way.

James read the phrase three times.

It had to refer to the hand signals.

Thomas Lawrence was asking Washington to help them create a photograph that preserved the Underground Railroad’s secret language.

But why? What was so important about preserving these signals in 1890 that a family would commission a special photograph? James photographed the letter, then turned his attention to the glass negatives.

Most showed typical Victorian portraits, but one stopped him cold.

It was another photograph taken the same day as the Lawrence family portrait, showing the same six people, but in this image, they stood instead of sitting, their hands in completely different positions.

This was a second pose, a companion image to the one James had purchased.

He held the glass plate up to the light.

In this version, Thomas Lawrence pointed with two fingers toward the ground.

His wife’s hands formed a triangle.

The eldest son’s arms were crossed with his hands gripping opposite elbows.

The second son held one hand palm up at waist level.

The daughter’s hands were clasped as if in prayer.

The youngest son’s hands were empty, hanging naturally at his sides.

These were different signals entirely.

The Lawrence family had not created one coded photograph, but two, each conveying a separate message.

Dorothy, I need to photograph this negative.

Can you develop it for me? She smiled.

We have a dark room.

Give me an hour.

While he waited, James walked through Philadelphia’s streets, trying to imagine the city as it had been in 1890.

The black community here had been substantial, composed of freed people, their descendants, and those who had escaped slavery before the war.

They had built churches, schools, businesses, and mutual aid societies.

When he returned, Dorothy handed him a newly printed photograph.

Seeing it developed and enlarged, James noticed more details.

Behind the family in this second image, partially visible in the studio’s background, was a shelf with books.

He could just make out some titles on the spines.

James returned to Boston with copies of both photographs and the letter.

He pinned them to his office wall, studying them for hours each day.

Students passing his open door would glimpse him standing motionless, staring at the images, lost in thought.

He focused on identifying the hand signals in the second photograph.

Cross referencing with the Underground Railroad documentation, he determined that Thomas Lawrence’s two-fingered point meant direction north.

The wife’s triangle symbolized safe harbor.

The eldest son’s crossed arms represented protection offered here.

The second son’s upturned palm meant provisions available.

The daughter’s prayer-like clasp signified faith community or church.

The youngest son’s empty hands were puzzling until James found a reference in an abolitionist diary.

Empty hands meant freedom achieved.

Together, the signal spelled out a message.

Journey north to safe harbor where protection and provisions are offered by the faith community.

Freedom achieved.

This was not just a family preserving history.

They were documenting something specific.

A particular place or event connected to the Underground Railroad.

But what place? And why was it still significant in 1890? James examined the book titles visible in the second photograph.

Using photo enhancement software, he could read two titles.

narrative of the life of Frederick Douglas and Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Both were landmark abolitionist works, but it was the third book, partially obscured, that proved crucial.

Through careful enhancement, he could make out Bard Street safe.

Lombard Street.

James searched for any connection between Lombard Street and the Underground Railroad.

What he found astonished him.

Mother Bethl African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded in 1794, stood at 419 South 6th Street in Philadelphia.

But the congregation had operated multiple properties.

One of their auxiliary buildings had been located on Lombard Street and served as a documented underground railroad station from 1850 to 1863.

The building had been sold in 1867 and converted to private residences.

James found city records showing that Thomas Lawrence had purchased the property at 247 Lombard Street in 1875.

He had lived there until his death in 1902.

The same building that had hidden freedom seekers before the Civil War had become the Lawrence family home.

But there was more.

James discovered a brief newspaper article from the Philadelphia Tribune, a black newspaper dated July 4th, 1890.

It announced that the property at 247 Lombard Street would be demolished the following year to make way for commercial development.

The Lawrence family would be forced to relocate.

Suddenly, everything made sense.

The family had not created these photographs simply to honor history.

They were creating a permanent record of the actual safe house where they had found freedom, preserving the signals that had guided them there before both the building and living memory disappeared forever.

James needed to know the Lawrence family story, but records of formerly enslaved people were notoriously difficult to trace.

Many had changed their names after gaining freedom, and official documentation was sparse or non-existent for people who had been considered property rather than persons.

He started with census records.

The 1890 census had been largely destroyed in a fire, but he found the Lawrence family in the 1880 Philadelphia census.

Thomas Lawrence, age 42, born in Maryland.

His wife Elizabeth, age 40, born in Virginia.

Their children, William, age 18.

Daniel, age 16, Sarah, age 14, and Joseph, a 12, all born in Pennsylvania.

The birthplaces were revealing.

Thomas and Elizabeth had been born in slave states, but their children were born in Pennsylvania, a free state.

This meant Thomas and Elizabeth had escaped slavery and reached Philadelphia before 1862 when their eldest son was born.

James searched Maryland and Virginia records for any mention of enslaved people named Thomas and Elizabeth who disappeared in the late 1850s or early 1860s.

It was like searching for shadows, but he persisted.

Finally, in a Maryland plantation ledger archived at the Library of Congress, he found an entry dated March 1861.

Slaves Thomas and Elizabeth absconded.

Reward offered for return.

The plantation belonged to a man named Richard Garrett in Talbet County, Maryland on the Eastern Shore.

James felt his pulse quicken.

The Eastern Shore had been one of the most active regions for Underground Railroad activity, largely because of its proximity to free states and the work of Harriet Tubman, who had been born there.

He found additional records showing that Garrett had advertised the escape in Baltimore newspapers, describing Thomas as a strong field, aged 23, and Elizabeth as a house servant, aged 21, with child.

Elizabeth had been pregnant when they escaped.

James calculated quickly.

If Elizabeth was pregnant in March 1861, and William was born in 1862, they had reached Philadelphia with barely months to spare.

They had made the dangerous journey while Elizabeth carried their first child, risking everything for a chance at freedom.

But how had they known about the safe house on Lombard Street? Who had guided them? What route had they taken? These questions led James to his next discovery.

He found a collection of letters at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, correspondence between members of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, an organization that aided escaped slaves.

One letter dated May 1861, mentioned the arrival of a young couple from Maryland, brought north by our friend from Delaware.

The friend from Delaware was almost certainly Thomas Garrett, a Quaker abolitionist based in Wilmington, who was one of the Underground Railroads most active conductors.

He had helped thousands of people escape and worked closely with Harriet Tubman.

James traveled to Wilmington, Delaware, where the Thomas Garrett papers were housed at the Delaware Historical Society.

The collection included detailed records of people Garrett had helped, including physical descriptions, dates, and sometimes names, though many were recorded only with initials to protect identities.

In a ledger from spring 1861, James found an entry that matched T and E from Talbet County.

Woman with child arrived March 29th, departed for Philadelphia March 31st, traveled with JM to safe station on Lombard.

JM James searched through other documents for those initials.

He found them attached to Jonathan Miller, a free black man who served as a conductor on the Philadelphia route.

Miller would meet freedom seekers in Wilmington and guide them the final miles to safe houses in Philadelphia.

James was piecing together the Lawrence family’s escape.

Thomas and Elizabeth had fled the Garrett plantation in late March 1861, probably traveling by night through Maryland’s network of safe houses.

They reached Thomas Garrett in Wilmington, who sheltered them briefly before sending them north with Jonathan Miller.

Miller brought them to the Lombard Street safe house where they arrived in early April 1861.

The timing was significant.

The Civil War began on April 12th, 1861 with the bombardment of Fort Sumpter.

Thomas and Elizabeth had escaped just days before the nation was torn apart.

They had spent those early war weeks hidden in the basement of the Lombard Street House, unable to move further north because of the chaos and increased scrutiny that came with the outbreak of war.

James found confirmation in another letter from the vigilance committee dated April 20th, 1861.

Several persons remain at our stations, unable to proceed to Canada due to heightened surveillance.

They are safe, but anxious.

Thomas and Elizabeth must have lived in that basement for weeks, perhaps months, as Elizabeth’s pregnancy progressed.

At some point, the family operating the safe house had helped them establish new identities with the surname Lawrence, had found Thomas work, and had helped them integrate into Philadelphia’s free black community.

Their son, William, was born in Philadelphia as a free child, the first Lawrence to be born into freedom.

But who had operated that safe house? who had risked everything to shelter them.

James needed to find out who owned the Lombard Street property in 1861.

Property records showed it belonged to Reverend Jacob Bennett and his wife Martha, members of Mother Bethl amme church.

The Bennett had operated the safe house from 1850 until the end of the war, sheltering an estimated 200 people.

James found a photograph of Reverend Bennett from 1865, a dignified man in his 50s.

Then he made a connection that sent chills down his spine.

James discovered that Martha Bennett, the reverend’s wife, had been photographed alongside the Lawrence family in 1890.

He found the image in the historical society’s collection, labeled simply community gathering, Mother Bethl Church, 1890.

Standing next to Thomas Lawrence was an elderly woman identified in the caption as Martha Bennett.

Her husband had died in 1876, but she had continued living in the Lombarded Street house until it was sold to Thomas Lawrence in 1875.

Thomas Lawrence had not just bought the house that sheltered him.

He had bought it from the woman who had hidden him in her basement 29 years earlier.

Martha Bennett had sold him the property and then continued living there as his guest, completing a circle of gratitude and connection that spanned decades.

James now understood the full significance of the photographs.

When the building was scheduled for demolition in 1891, Thomas Lawrence wanted to create something that would outlast brick and mortar.

He wanted to preserve not just the memory of the safe house, but the secret language that had saved his life and the lives of his family.

The hand signals in the first photograph were those Thomas and Elizabeth would have used during their escape.

The signals that identified them as freedom seekers that communicated their needs that connected them with helpers along the route.

The signals in the second photograph represented the safe house itself, documenting its purpose and the role it played in the Underground Railroad network.

But James still had questions.

Why had the family kept these photographs private? Why had they never been displayed or published? And what had happened to the descendants? He searched for death records and found that Thomas Lawrence died in 1902, Elizabeth in 1905.

Their children had scattered.

William had moved to New York, Daniel to Chicago, Sarah had married and remained in Philadelphia, and Joseph had gone west to California.

The family line had branched and spread as families do.

James tracked down modern descendants through genealogy databases and church records from Mother Bethlme, which had maintained detailed membership lists.

He found Sarah’s great-g granddaughter, a woman named Patricia, who lived in Atlanta, Georgia.

He wrote to her explaining his research and asking if she knew anything about the photographs.

Patricia responded within a week.

She invited James to visit her, saying she had something to show him.

In January, James flew to Atlanta and met Patricia at her home, a comfortable house in a treelined neighborhood.

Patricia, a retired teacher in her 70s, greeted him with warmth and curiosity.

My grandmother told me stories about the Lombard Street House, Patricia said, leading James to her dining room.

She said it was sacred ground, that people had prayed there for freedom and found it.

She opened a cedar chest and carefully lifted out a cloth wrapped bundle.

Inside were the two original photographs, the negatives and something else.

A third photograph James had never seen.

The third photograph showed the same Lawrence family, but this time they were joined by Martha Bennett and Augustus Washington Jr.

himself.

Eight people stood together in the studio and their hands told yet another story.

This photograph had never been part of any archive or collection.

It had been kept privately by the Lawrence family for over a century, passed from generation to generation with strict instructions about its significance.

Patricia explained that her grandmother had told her it was never to be displayed publicly during the lifetimes of anyone in the photograph or their children, a request that had been honored until now, more than 130 years later.

James studied the hand positions in this final photograph.

Each person’s hands formed signals, but these were not the Underground Railroad codes he had been studying.

These signals were simpler, more universal.

hands clasped in friendship, hands placed over hearts, hands extended in gestures of offering and acceptance.

Patricia handed James a letter yellowed with age, written by Thomas Lawrence in 1901, a year before his death.

It had been enclosed with the photographs and preserved in the cedar chest.

James read it aloud to my descendants who will read this long after I’m gone.

These photographs tell the story of our family’s journey from bondage to freedom, from fear to safety, from desperation to hope.

The hand signals you see were the silent language that saved our lives when words could bring capture and death.

We created these images not to glorify ourselves, but to honor those who helped us and to ensure that the courage and sacrifice of the Underground Railroad would never be forgotten.

The house on Lombard Street where we first tasted freedom is being torn down.

But its spirit lives in these photographs.

Remember that freedom is never free.

It is bought with courage, maintained with vigilance, and passed on through testimony.

Let these images speak across the generations of the price paid and the debts owed.

We were strangers taken in and we became family.

That is the greatest testament of all.

James felt emotion rise in his throat as he finished reading.

Patricia was crying softly.

My grandmother said those hand signals were a language of survival.

She said, but in that last photograph, they became a language of love and gratitude.

James looked again at the third photograph, seeing it now with complete understanding.

The signals were simpler because the message was simpler.

We survived together.

We honored each other.

We became family.

Patricia agreed to allow the photographs to be exhibited publicly for the first time.

James worked with the National Museum of African-American History and Culture to create an exhibition that told the Lawrence family’s complete story.

From their escape in 1861 to their determination to preserve the memory of those who helped them.

The exhibition opened in the spring and thousands came to see the photographs and learn about the secret language of the Underground Railroad.

Descendants of other families who had used the Lombard Street safe house came forward with their own stories, adding depth and detail to the historical record.

James stood in the gallery on opening day, watching visitors examine the photographs, reading the hand signals, understanding for the first time the complex web of courage and communication that had saved thousands of lives.

A young girl, perhaps 10 years old, stood before the first Lawrence family photograph, her own hands unconsciously mimicking the signals.

“What do they mean?” she asked her mother.

They mean freedom, her mother answered.

And they mean that some things are too important to forget.

James thought about the journey that had brought him here.

From a rainy morning in a Boston auction house to this moment of revelation and recognition, the Lawrence family had succeeded in their mission.

They had preserved not just the memory of the Underground Railroad, but its very language hidden in plain sight in a photograph that waited more than a century to tell its truth.

The photograph that seemed so ordinary at first glance had indeed changed history.

Not by revealing something entirely unknown, but by preserving something precious that had been slipping away.

The testimony of survival, the language of liberation, and the enduring power of those who risk everything to help others reach freedom.

Outside the museum, spring rain began to fall, gentle and cleansing, like the rain that had fallen that distant morning when James first held the photograph in his hands and wondered what secrets it contained.

Now the secrets were revealed, the silence was broken, and the Lawrence family’s message had finally reached across a century to touch the world they had dreamed their descendants would inherit.

A world that remembered.

A world that honored.

News

🚛 HIGHWAY CHAOS — TRUCKERS’ REVOLT PARALYZES EVERY LAND ROUTE, KHAMENEI SCRAMBLES TO CONTAIN THE FURY 🌪️ The narrator’s voice drops to a biting whisper as convoys snake through empty highways, fuel depots go silent, and leaders in Tehran realize this isn’t just a protest — it’s a nationwide blockade that could topple power and ignite panic across the region 👇

The Reckoning of the Highways: A Nation on the Edge In the heart of Tehran, the air was thick with…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Darkened City: A Night of Reckoning In the heart of Moscow, a city that once stood proud and unyielding,…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Shocking Resurrection: A Hollywood Revelation In a world where faith intertwines with fame, the announcement sent ripples through the…

🎬 “TO THIS DAY, NO ONE CAN EXPLAIN IT” — JIM CAVIEZEL BREAKS YEARS OF SILENCE ABOUT THE MYSTERY THAT HAUNTED HIM AFTER FILMING ⚡ In a hushed, almost trembling confession, the actor leans back and stares past the lights, hinting at strange accidents, eerie coincidences, and moments on set that felt less like cinema and more like something watching from the shadows, leaving even hardened crew members shaken to their core 👇

The Unseen Shadows: Jim Caviezel’s Revelation In the dim light of a secluded room, Jim Caviezel sat across from the…

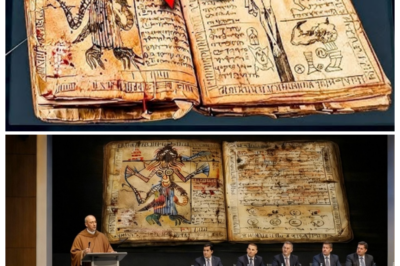

📜 SEALED FOR CENTURIES — ETHIOPIAN MONKS FINALLY RELEASE A TRANSLATED RESURRECTION PASSAGE, AND SCHOLARS SAY “NOTHING WILL BE THE SAME” ⛪ The narrator’s voice drops to a breathless whisper as ancient parchment cracks open under candlelight, hooded figures guard the doors, and words once locked inside stone monasteries spill out, threatening to shake faith, history, and everything believers thought they understood 👇

The Unveiling of Truth: A Resurrection of Belief In the heart of Ethiopia, where the ancient echoes of faith intertwine…

🕯️ FINAL CONFESSION — BEFORE HE DIES, MEL GIBSON CLAIMS TO REVEAL JESUS’ “MISSING WORDS,” AND BELIEVERS ARE STUNNED INTO SILENCE 📜 The narrator’s voice drops to a hushed, dramatic whisper as old notebooks open, candlelight flickers across ancient pages, and Gibson hints that lines never recorded in scripture could rewrite everything the faithful thought they knew 👇

The Unveiling of Hidden Truths In the dim light of his private study, Mel Gibson sat surrounded by piles of…

End of content

No more pages to load