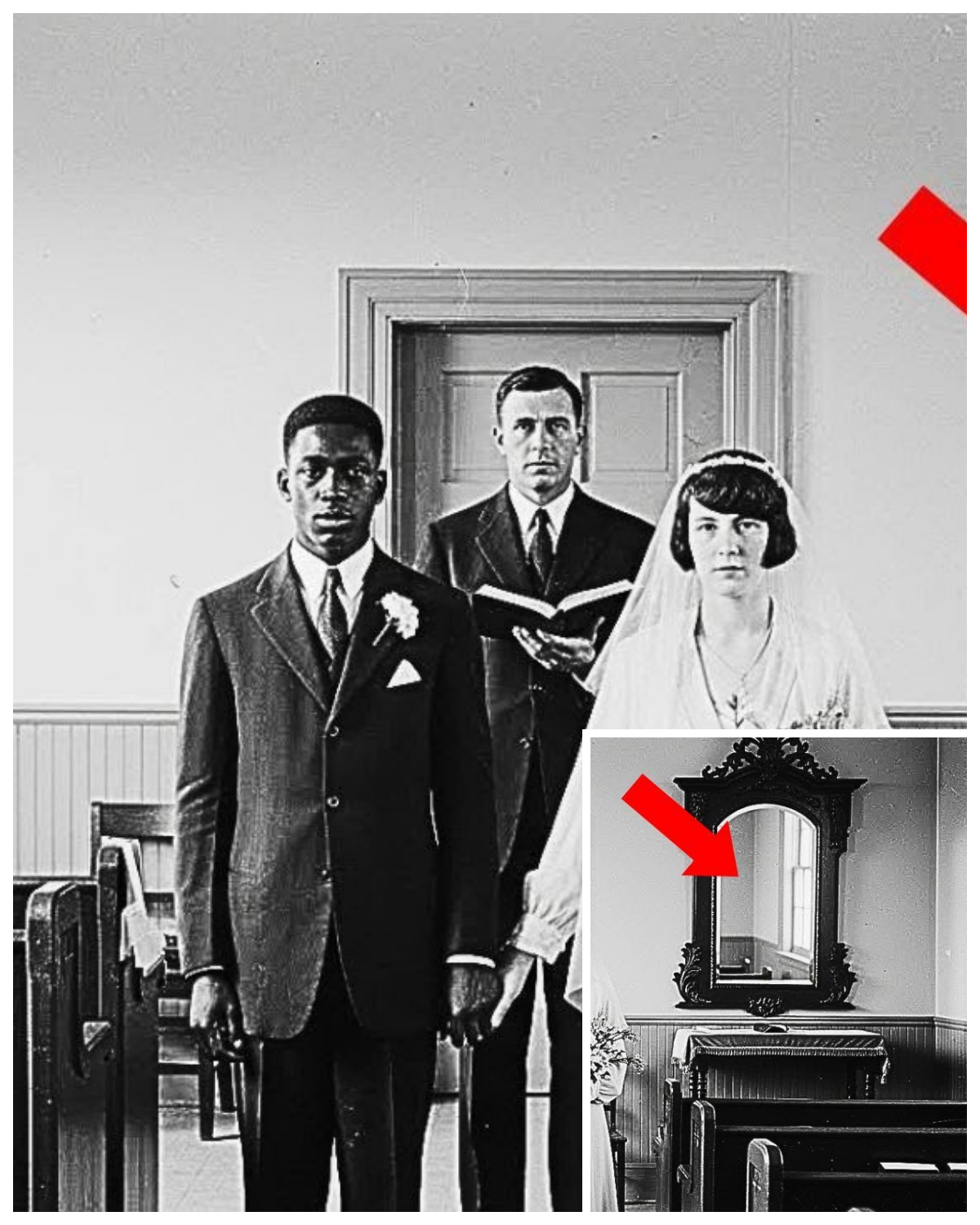

This 1925 wedding photo has been restored, and what appeared in the mirror shocked historians.

The photograph arrived at the Detroit Historical Society on a humid Tuesday morning in June, wrapped in yellow tissue paper and accompanied by a handwritten note.

My grandmother’s wedding, 1925.

Please preserve this.

Marcus Williams, the society’s lead photo restoration specialist, carefully unwrapped the fragile image and placed it under his magnifying lamp.

The black and white photograph showed a small church interior, simple wooden pews visible in the background.

At the center stood a young couple, a white woman in a modest cream colored dress holding a bouquet of wild flowers, and a black man in a well-pressed dark suit, his hand gently resting on hers.

Their faces radiated quiet joy despite the obvious tension in their postures.

Behind them, a Baptist minister held an open Bible, his expression solemn but kind.

Marcus had seen countless wedding photos in his 15 years at the society, but something about this one made him pause.

The couple’s body language suggested both love and fear.

The way they leaned slightly toward each other, as if drawing strength from proximity.

He knew what an interracial marriage in 1925 Detroit meant.

It wasn’t just unusual, it was dangerous.

As he began the digital scanning process, adjusting the contrast and exposure, Marcus noticed something odd in the background.

On the right side of the frame, partially visible, was an ornate mirror hanging on the church wall.

The mirror’s barack frame seemed out of place in the humble chapel, likely donated by a wealthier congregation member.

Marcus zoomed in on the mirror’s reflection, expecting to see perhaps the photographer or more guests.

Instead, his breath caught.

There, clearly visible in the silvered glass, was a figure standing at the church’s side window, a man whose face was partially obscured by what appeared to be a hood or covering.

His hands trembled slightly as he increased the magnification.

The figure wasn’t inside the church.

He was outside watching through the window.

The posture suggested surveillance, perhaps menace.

Marcus felt a chill run down his spine.

He saved the enhanced image and sat back in his chair, staring at the screen.

Who was this person? Why was he watching the wedding? And why had no one noticed him in nearly a century? Marcus picked up the note that came with the photograph and read it again, this time searching for a return address.

There was a phone number scrolled at the bottom.

He reached for his phone, then hesitated.

Before calling the family, he needed to know more.

This photograph held a story that went far beyond a simple wedding ceremony.

Marcus spent the rest of the afternoon combing through the society’s archives, searching for any reference to interracial marriages in Detroit during the 1920s.

The records were sparse.

Most such unions were kept quiet, conducted in private homes or sympathetic churches willing to risk community backlash.

The Ku Klux Clan had experienced a massive resurgence during that decade with membership reaching into the millions nationwide.

In Detroit, the organization held rallies, influenced local politics, and terrorized black residents and anyone who challenged racial boundaries.

He pulled out a leatherbound ledger containing newspaper clippings from 1925.

The Detroit Free Press and Detroit News had extensively covered clan activities, marches down Woodward Avenue, cross burnings in public parks, intimidation campaigns against black families moving into white neighborhoods.

One article from August 1925 caught his attention.

Threats against mixed marriage ceremony.

Couple fleas city.

The article was brief, offering few details and no names, citing privacy concerns and ongoing investigations.

It mentioned that a wedding had been planned at an unnamed Baptist church on Detroit’s east side, that the couple had received threatening letters and that they ultimately left the city before the ceremony could take place.

But Marcus was holding a photograph of a wedding that clearly had taken place.

Either this article referred to a different couple or something in the official record was incomplete.

He photographed the article with his phone and returned to his computer, pulling up census records and church registries.

Detroit in 1925 had dozens of Baptist churches, but only a handful served predominantly black congregations and would have been willing to perform such a ceremony.

Marcus cross referenced the architectural details visible in the photograph.

The specific style of wooden pews, the window placement, the ways coating along the walls.

After an hour of comparison, he narrowed it down to three possibilities.

Bethl Baptist, Second Baptist, or a smaller chapel called Friendship Baptist that had been demolished in the 1960s.

He leaned back and rubbed his tired eyes.

The sun was setting outside his office window, casting long shadows across his desk.

The photograph lay beside his keyboard, the couple’s faces gazing up at him with that mixture of hope and apprehension.

Who were they? Had they survived whatever threat the hooded figure represented? And why had their story been erased from the official record? Marcus glanced at the phone number on the note again.

Tomorrow, he would call.

Tonight, he needed to learn everything he could about what this couple had faced.

The next morning, Marcus dialed the number with a mixture of anticipation and nervousness.

After three rings, a woman’s voice answered, warm but cautious.

Hello.

Good morning.

My name is Marcus Williams.

I’m calling from the Detroit Historical Society.

I received a photograph you sent us.

A wedding photo from 1925.

There was a pause, then a soft intake of breath.

Yes, that’s my grandmother’s wedding.

I’m Dorothy.

Dorothy Harrison.

Marcus chose his words carefully.

Ms.

Harrison.

I’ve been examining the photograph and I’ve discovered something unusual in it.

Would you be willing to meet with me? I’d like to learn more about your grandmother and the circumstances of this wedding.

Another pause.

What did you find? I’d prefer to show you in person if that’s possible.

I think there’s more to this photograph and your family’s story than what appears on the surface.

Dorothy agreed to meet him that afternoon at a cafe near the historical society.

When Marcus arrived, he immediately recognized her, a woman in her late 60s with kind eyes and silver hair pulled back in a neat bun.

She stood as he approached, shaking his hand firmly.

After they ordered coffee, Marcus opened his laptop and turned it toward her.

This is the photograph you sent us.

He zoomed in on the mirror, and this is what I found in the reflection.

Dorothy leaned forward, squinting at the screen.

Her hand went to her mouth.

“Oh my god,” she whispered.

Do you know who that might be? Marcus asked gently.

Dorothy sat back, her eyes filling with tears.

My grandmother never talked much about her wedding day.

She would only say that it was the bravest thing she ever did and that she wasn’t alone.

The people she barely knew risked everything to make sure she and my grandfather could marry safely.

She pulled a tissue from her purse and dabbed her eyes.

My grandmother was Ruth.

Ruth Morrison before she married.

She was 22 years old, working as a seamstress in a downtown shop.

My grandfather was Thomas.

Thomas Wheeler, he was 25, worked at the Ford plant on the assembly line.

How did they meet? Marcus asked.

At a jazz club on Hastings Street.

Ruth’s employer had sent her to deliver a dress to a customer who lived nearby.

She got lost and wandered into the club by accident.

Thomas was there after his shift.

He helped her find her way, and they started talking.

Within 3 months, they knew they wanted to marry.

Dorothy paused, staring at the photograph.

But Ruth’s father was furious.

Not just because Thomas was black, but because he knew what it would mean for her, the danger, the isolation.

And Thomas’s family was terrified, too.

They’d heard stories of couples being attacked, killed even.

Dorothy wrapped her hands around her coffee cup, her gaze distant.

As she continued, “My grandmother told me that the threats started almost immediately after word got out about their engagement.

Someone left a note on Thomas’ doorstep, just a simple piece of paper with a drawing of a noose and the date they planned to marry.

” Marcus felt his jaw tighten.

Did they go to the police? Dorothy gave a bitter laugh.

The police? Some of them were clan members themselves or sympathizers at least.

No.

Going to the police would have only made things worse.

Instead, Thomas went to his pastor at Friendship Baptist Church, Reverend Samuel Price.

He was an older man, had been preaching in Detroit since before the Great Migration.

He’d seen plenty of hatred in his time, but he wasn’t afraid of it.

She took a sip of her coffee before continuing.

Reverend Price told them he would perform the ceremony, but they had to understand the risks.

He’d married one other mixed couple 5 years earlier, and their house had been burned down 3 weeks after the wedding.

The couple had fled to Chicago and never came back.

Marcus made notes on his tablet, his mind racing with questions.

But Ruth and Thomas decided to go through with it anyway.

They did, but Reverend Price insisted on precautions.

The ceremony would be small, just immediate family and a few close friends.

It would be held on a Wednesday morning when most people would be at work, and he would only tell people the exact date and time 24 hours in advance to prevent word from spreading.

Dorothy pulled an old envelope from her purse and slid it across the table to Marcus.

Inside was a brittle yellowed letter written in careful cursive.

This is from Ruth’s diary.

She wrote this the night before the wedding.

Marcus carefully unfolded the letter and began to read.

Ruth’s words were simple but powerful.

Tomorrow I marry Thomas and I’m more afraid than I have ever been in my life.

But I am also more certain.

We have decided that love is worth the risk.

That our lives together are worth fighting for.

Reverend Price says that God does not see color, only hearts.

I believe him, and I believe that no matter what happens tomorrow, we will have chosen love over fear.

That has to count for something.

Marcus looked up, his throat tight.

She was incredibly brave.

They both were, Dorothy said quietly.

But they weren’t alone in their bravery.

That’s what I learned later after my grandmother finally told me the whole story.

The black community on the east side.

People who barely knew Thomas and Ruth.

They organized something that night before the wedding.

Something my grandmother didn’t know about until years later.

Dorothy ordered another coffee before continuing, her voice growing stronger with each memory she shared.

The night before the wedding, Thomas’s coworker from the Ford plant, a man named James, who lived three blocks from Friendship Baptist, knocked on doors throughout the neighborhood.

He didn’t announce what was happening or why.

He simply said, “Tomorrow morning, we need people to stand watch at the church.

Can we count on you?” Marcus leaned forward, captivated.

“Stand watch.

” By dawn, more than 30 people had volunteered.

Factory workers, shopkeepers, domestic workers, teachers from the colored school, people who had their own jobs and families to worry about, but who understood what was at stake.

They knew that if the clan discovered the ceremony, there would be violence.

So, they created a plan.

Dorothy pulled out another photograph from her purse.

This one showing a street corner with Friendship Baptist visible in the background.

James organized the volunteers into shifts.

Some would position themselves at street corners blocks away, watching for any suspicious activity, groups of white men in cars, anyone wearing clan regalia, anything unusual.

Others would station themselves closer to the church, ready to warn everyone inside if danger approached.

“And the man in the mirror, the hooded figure,” Marcus asked, his heart racing.

That was Isaiah, Dorothy said softly.

Isaiah Turner.

He was a veteran.

Had served in France during the Great War with the 369th Infantry Regiment, the Harlem Hell Fighters.

When he came back to Detroit, he worked as a night watchman at a warehouse.

James asked him specifically to watch the church’s side window because he had the best vantage point from there in military training that might prove useful.

Marcus zoomed in on the hooded figure again, seeing him with new eyes.

So, he wasn’t a threat.

He was protection.

Exactly.

But he had to stay hidden.

If anyone passing by saw a black man obviously standing guard at a church, it might attract attention and raise questions.

So he wore an old coat with a hood and positioned himself where he could see both the street and the church interior through that side window.

He stood there for 3 hours from the time the first guests arrived until the ceremony ended and everyone had safely dispersed.

Marcus felt a wave of emotion wash over him.

The photograph had captured so much more than a wedding ceremony.

It had documented an entire community’s quiet act of resistance and protection.

“Did Ruth and Thomas know about all this at the time?” he asked.

Dorothy shook her head.

Not until years later.

They thought they were alone, taking their risk in isolation.

But decades afterward at Thomas’s retirement party from Ford in 1968.

Isaiah attended.

He was elderly by then, using a cane.

He approached Ruth and finally told her what he and the others had done that day.

Dorothy’s eyes grew distant as she recounted the story her grandmother had told her.

Ruth said she woke up that Wednesday morning with her stomach in knots.

Her father had refused to attend.

He’d disowned her when she wouldn’t call off the engagement.

Her mother came though, sneaking out while he was at work.

She helped Ruth into the cream colored dress she’d sewn herself, working on it late at night by lamplight after her seamstress shifts.

Marcus imagined the scene, the young bride’s trembling hands, the weight of her decision pressing down on her shoulders.

Thomas had borrowed a suit from his older brother.

Ruth said he looked so handsome when she arrived at the church that morning, but his eyes betrayed his fear.

They held hands in the small room behind the sanctuary, waiting for Reverend Price to signal that everyone had arrived and it was safe to begin.

Dorothy paused, her voice catching.

There were only 12 people in that church.

Ruth’s mother, Thomas’s parents and two siblings, three couples from the congregation who Reverend Price trusted completely, and one photographer, a man named Albert, who had a small studio on Hastings Street and who agreed to document the wedding for just $5 instead of his usual rate.

Albert is the one who took this photograph, Marcus asked.

Yes.

Ruth said he only took four photographs total.

They couldn’t afford more, and he needed to work quickly.

This was the third one taken right after they exchanged vows.

She remembered hearing the camera’s shutter click, remembered how the flash powder made her blink, how Thomas squeezed her hand as if to say, “We did it.

We’re married.

” Marcus studied the photograph again, seeing the couple’s intertwined hands, the relief beginning to show through their nervous expressions.

But what they didn’t know, Dorothy continued, was that outside, Isaiah was watching a black car circle the block for the second time.

He’d noticed it during the first pass and kept his eye on the street.

When it came around again, slowing down near the church, he tensed.

Through the window, he could see the ceremony continuing inside.

Reverend Price speaking, Ruth and Thomas focused entirely on each other and the sacred moment they were sharing.

Marcus held his breath, waiting for Dorothy to continue.

The car stopped directly in front of the church.

Three white men got out, and Isaiah could see they were carrying something.

His military training kicked in immediately.

He couldn’t leave his post to warn those inside without being seen, so he did the only thing he could.

He stepped fully into the window’s view, making himself visible to the men, and stood completely still, staring directly at them.

Dorothy’s voice dropped to almost a whisper as she described what happened next.

Isaiah told my grandmother years later that those three men stared back at him for what felt like an eternity.

He was wearing that hooded coat, standing motionless in the window like a sentinel.

They couldn’t see his face clearly, couldn’t tell if he was alone, or if there were others inside watching them, too.

Marcus could picture it.

The standoff between Isaiah and the men who had come to disrupt the ceremony, perhaps worse.

One of the men started toward the church entrance, and that’s when James appeared.

He’d been positioned at the corner and had seen the car stop.

He walked casually down the sidewalk, not hurrying, not looking directly at the men, but making his presence known.

Then another volunteer, a woman named Clara, who ran a boarding house nearby, came out of her building and started sweeping her front steps, which happened to be right next to the church.

Dorothy smiled slightly.

Within two minutes, five other volunteers had materialized on that street.

All going about seemingly innocent business, sweeping, checking mailboxes, having a conversation on a stoop.

But the message was clear.

This church was not unprotected.

Whatever these men had planned, they would not be able to do it quietly or without witnesses.

“What did the men do?” Marcus asked, completely absorbed in the story.

They got back in their car and drove away.

Isaiah watched them disappear down the street, his heart pounding so hard he thought it might burst.

Inside the church, Ruth and Thomas were exchanging rings, completely unaware of what had just transpired outside.

Reverend Price was pronouncing them husband and wife.

Albert was taking the fourth and final photograph.

Marcus felt a profound sense of awe.

So, the wedding continued without interruption.

It did.

When Reverend Price said, “You may kiss your bride.

” Thomas and Ruth finally allowed themselves to breathe, to believe they had actually done it.

They’d married despite everything.

The threats, the social condemnation, the very real danger, and they’d survived.

Dorothy pulled out a handkerchief and wiped her eyes.

But survival was only the beginning.

The real challenge was building a life together in a city that didn’t want them to exist as a couple.

Reverend Price advised them to be cautious, to keep a low profile.

He suggested they consider moving to a more mixed neighborhood or even leaving Detroit altogether.

“Did they leave?” Marcus asked.

“No,” Thomas refused.

He said that if they ran, it would mean the hatred had won.

Ruth agreed.

They found a small apartment on the east side in a building where the landlord was willing to rent to them.

Thomas kept his job at Ford.

Some co-workers gave him cold shoulders, but others, particularly fellow black workers, quietly supported him.

Ruth had to quit her seamstress job when her employer discovered her marriage, but she eventually found work doing alterations from home.

Marcus spent the next several days researching Friendship Baptist Church in the East Side neighborhood where Ruth and Thomas had built their life.

He discovered that the church had been a center of civil rights activity long before the modern movement, a place where Frederick Douglas had once spoken, where underground railroad conductors had sought refuge, where the community gathered to resist injustice.

He found Thomas’ employment records at the Ford Motor Company archives.

Thomas had worked on the assembly line for 42 years from 1923 until his retirement in 1965.

The records showed steady employment, no disciplinary actions, and eventually a promotion to line supervisor, notable because black workers rarely advanced to supervisory positions in that era.

Marcus also discovered something else, a brief mention in a 1927 church newsletter that Reverend Price had received threats after performing controversial marriages and that the congregation had organized a protection committee.

The newsletter didn’t provide details, but it confirmed Dorothy’s account.

When Marcus called Dorothy with his findings, she invited him to her home in suburban Detroit.

There’s more I want to show you,” she said.

“Things my grandmother left me when she passed.

” Dorothy’s house was filled with family photographs spanning generations.

She led Marcus to her dining room table where she’d laid out several items.

A worn Bible, a leatherbound journal, and a small wooden box.

“This was Ruth’s Bible,” Dorothy explained, opening the worn cover.

Inside, pressed between the pages of the book of Ruth, was a dried wild flower, one from her wedding bouquet.

She kept this her entire life.

She said it reminded her that beauty can survive even in difficult soil.

The journal contained Ruth’s entries from 1925 through 1930.

Marcus carefully turned the pages, reading snippets of her daily life.

The entries were matterof fact, describing work, meals, visits with Thomas’s family, small joys, and frustrations.

But occasionally there were hints of the struggles they faced.

June 15th, 1926.

A woman spat at me today while I was walking to the market.

Thomas says I shouldn’t let it bother me.

That her hate says more about her than about us.

He’s right, but it still hurt.

October 3rd, 1927.

Thomas came home upset today.

Someone at the plant called him a traitor to his race for marrying me.

He didn’t tell me who.

I hate that he has to carry that burden.

April 22nd, 1928.

We’re going to have a baby.

I’m terrified and overjoyed all at once.

What kind of world are we bringing this child into? But Thomas took my hands tonight and said, “We’re building a better world by refusing to let hate win.

” “I believe him.

” Marcus looked up at Dorothy.

“Your mother?” she nodded.

Margaret, born in January 1929, and despite everything Ruth and Thomas feared, she grew up loved and strong.

Dorothy opened the wooden box and carefully removed several items.

A bronze medallion, a faded newspaper clipping, and a letter dated 1968.

After Isaiah told Ruth and Thomas about the protection that day, Thomas tracked down as many of the volunteers as he could find.

Some had moved away, some had passed on, but he found 12 of them still living in Detroit.

He invited them all to a dinner at his house.

She handed Marcus the newspaper clipping, a small announcement from the Michigan Chronicle, a black newspaper dated November 1968.

Community gathers to honor unsung heroes.

The brief article mentioned a private ceremony honoring citizens who had protected their neighbors during difficult times, but provided no specific details.

“Thomas had these medallions made,” Dorothy continued, showing Marcus the bronze piece.

It was simple, engraved with the words, “Friendship Baptist, 1925, and a pair of clasped hands.

He gave one to each person who had stood watch that day.

Isaiah’s daughter sent this one to us after he passed away in 1972.

She said he kept it on his bedside table until the day he died.

” Marcus turned the medallion over in his hands, feeling the weight of history it carried.

But the most important thing, Dorothy said, pulling out the letter, is what Ruth wrote to Isaiah after that dinner.

I found it in her papers after she passed.

She never sent it.

I think she felt it couldn’t capture everything she wanted to say, but she wrote it anyway.

Marcus read Ruth’s words written in an elderly shaking hand.

Dear Isaiah, how do I thank you for something I didn’t even know you did? For 43 years, Thomas and I thought we had married alone, that our courage was ours alone.

To learn now that we were surrounded by such love, such bravery from people who barely knew us.

It has rewritten my entire understanding of that day.

You didn’t just protect our wedding.

You protected our belief in humanity.

You showed us that we are not defined by the worst people among us, but by the best.

That wedding photograph that Albert took, I’ve looked at it thousands of times over the decades.

I’ve studied our faces, remembered our fear, marveled that we survived.

Now I will look at it differently.

Now I know that just outside the frame, just beyond what the camera could see, there were guardian angels watching over us.

Not divine angels, but human ones.

People like you who chose courage over comfort, solidarity over safety.

I cannot repay that debt, but I can make sure the world knows what you did.

Marcus felt tears prick his eyes.

She wanted the story told.

Dorothy nodded, but she never knew how.

The people who had helped them wanted to remain anonymous.

Some still feared repercussions even decades later.

And Ruth worried that telling the story would sound like she was bragging or seeking attention.

So the story stayed within the family, passed down through whispers and fragments.

3 months after his first meeting with Dorothy, Marcus stood in the Detroit Historical Society’s main gallery, watching visitors gather for the opening of a new exhibition.

The centerpiece was the restored wedding photograph enlarged to 4 ft wide, mounted on a wall painted deep blue.

Beside it was a smaller enhanced image showing Isaiah’s reflection in the mirror along with detailed explanatory text.

But the photograph wasn’t alone.

Marcus and Dorothy had spent weeks gathering additional materials.

Census records showing where Ruth and Thomas had lived, Thomas’ employment history, pages from Ruth’s journal, photographs of Friendship Baptist Church, and oral histories from descendants of the other volunteers who had stood watch that day.

The exhibition was titled Love and Solidarity, an untold story of courage in 1925 Detroit.

It told not just Ruth and Thomas’ story, but the story of an entire community that chose to protect rather than punish, to embrace rather than exclude.

Dorothy stood beside Marcus, watching a young couple read the text panels carefully, pausing at each photograph.

“Do you think this is what Ruth wanted?” she asked quietly.

“I think,” Marcus said.

that Ruth wanted people to know that love survives, not because it’s easy, but because people choose to protect it.

That’s what this exhibition shows.

An elderly black man approached them, leaning on a cane.

I knew Thomas, he said, his voice thick with emotion.

Worked with him at Ford in the 50s.

Never knew this story, though.

He never talked about it.

They didn’t want glory, Dorothy explained.

They just wanted to live.

The man nodded slowly.

And because of all those people who helped them, they got too.

That matters.

That matters more than folks realize.

But as the gallery filled with visitors, students, historians, families, Marcus watched them engage with the photograph that had started it all.

They leaned in close, studying the mirror, seeing Isaiah’s hooded figure watching over the ceremony.

They read Ruth’s words from her journal.

They learned the names of the volunteers who had positioned themselves on street corners and stoops, ready to defend two people they barely knew.

Later that evening, after the gallery had closed, Marcus and Dorothy stood alone in front of the photograph.

The couple in the image gazed back at them, their hands clasped, their faces showing that mixture of fear and determination that had first captured Marcus’ attention months ago.

“Every time I look at this,” Dorothy said, “I see something new.

Not just what’s in the frame, but what’s beyond it.

The invisible web of courage and love that made that moment possible.

” Marcus smiled.

That’s the power of photographs.

They capture one moment, but they contain multitudes.

Every photograph is a mirror really reflecting not just what was but who we are and what we choose to

News

🚛 HIGHWAY CHAOS — TRUCKERS’ REVOLT PARALYZES EVERY LAND ROUTE, KHAMENEI SCRAMBLES TO CONTAIN THE FURY 🌪️ The narrator’s voice drops to a biting whisper as convoys snake through empty highways, fuel depots go silent, and leaders in Tehran realize this isn’t just a protest — it’s a nationwide blockade that could topple power and ignite panic across the region 👇

The Reckoning of the Highways: A Nation on the Edge In the heart of Tehran, the air was thick with…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Darkened City: A Night of Reckoning In the heart of Moscow, a city that once stood proud and unyielding,…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Shocking Resurrection: A Hollywood Revelation In a world where faith intertwines with fame, the announcement sent ripples through the…

🎬 “TO THIS DAY, NO ONE CAN EXPLAIN IT” — JIM CAVIEZEL BREAKS YEARS OF SILENCE ABOUT THE MYSTERY THAT HAUNTED HIM AFTER FILMING ⚡ In a hushed, almost trembling confession, the actor leans back and stares past the lights, hinting at strange accidents, eerie coincidences, and moments on set that felt less like cinema and more like something watching from the shadows, leaving even hardened crew members shaken to their core 👇

The Unseen Shadows: Jim Caviezel’s Revelation In the dim light of a secluded room, Jim Caviezel sat across from the…

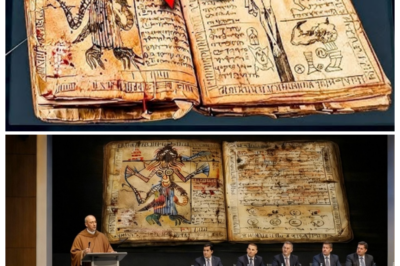

📜 SEALED FOR CENTURIES — ETHIOPIAN MONKS FINALLY RELEASE A TRANSLATED RESURRECTION PASSAGE, AND SCHOLARS SAY “NOTHING WILL BE THE SAME” ⛪ The narrator’s voice drops to a breathless whisper as ancient parchment cracks open under candlelight, hooded figures guard the doors, and words once locked inside stone monasteries spill out, threatening to shake faith, history, and everything believers thought they understood 👇

The Unveiling of Truth: A Resurrection of Belief In the heart of Ethiopia, where the ancient echoes of faith intertwine…

🕯️ FINAL CONFESSION — BEFORE HE DIES, MEL GIBSON CLAIMS TO REVEAL JESUS’ “MISSING WORDS,” AND BELIEVERS ARE STUNNED INTO SILENCE 📜 The narrator’s voice drops to a hushed, dramatic whisper as old notebooks open, candlelight flickers across ancient pages, and Gibson hints that lines never recorded in scripture could rewrite everything the faithful thought they knew 👇

The Unveiling of Hidden Truths In the dim light of his private study, Mel Gibson sat surrounded by piles of…

End of content

No more pages to load