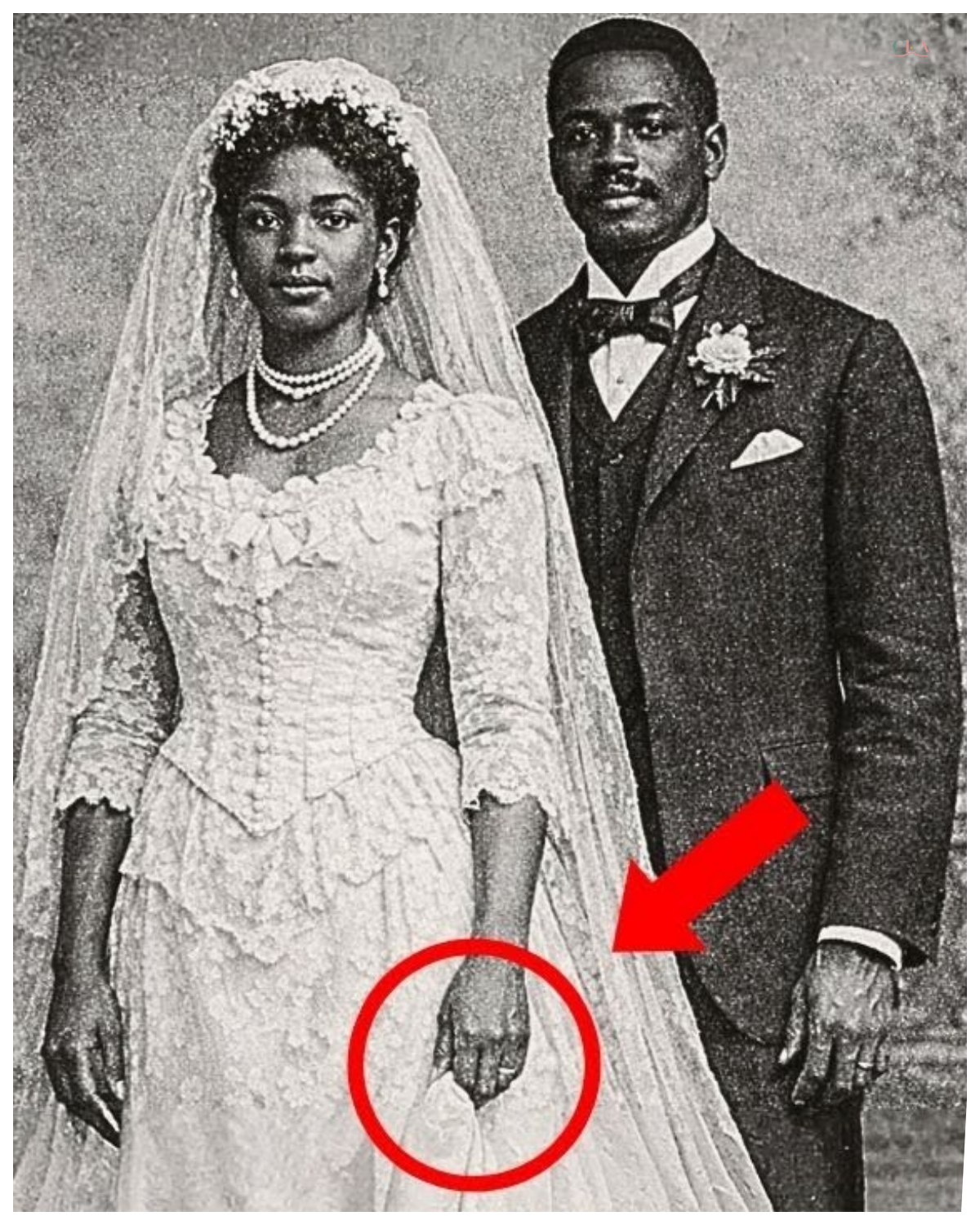

This 1920 Wedding Portrait Looked Joyful — Until You Notice What the Bride Hides in Her Hand

This 1920 wedding portrait looked joyful until you notice what the bride hides in her hand.

David Harper had seen thousands of photographs in his 15 years as a historian at the New Orleans Heritage Museum, but something about this particular portrait stopped him cold.

It was a humid Tuesday afternoon in April 2024 when he unpacked the latest donation from the estate of Eleanor Rouso, a woman who had passed away at 103, leaving behind boxes of family memorabilia that no living relative wanted to claim.

The photograph was tucked between layers of yellowed tissue paper, its silver frame, tarnished but intact.

David carefully lifted it into the light streaming through his office window.

The image showed a black wedding couple from 1883.

The bride in an ivory dress with delicate lace sleeves and a long veil.

The groom in a crisp dark suit with a bineer pinned to his lapel.

They stood before an ornate backdrop typical of professional portrait studios of that era.

Their expressions captured in that peculiar stillness that early cameras demanded.

The bride was striking, not conventionally beautiful by the standards of the time, but there was something magnetic about her direct gaze into the lens.

Her dark hair was styled elegantly beneath her veil, and a strand of pearls circled her neck.

The groom stood slightly behind her, one hand resting formally on her shoulder, his face composed in solemn dignity.

For a black couple to afford such a formal portrait in 1883, Louisiana, barely 18 years after the end of slavery, spoke volumes about their determination to document this moment, to claim their place in history.

David turned the frame over, searching for any inscription or identifying marks.

On the back, written in faded brown ink, were simply two names, Clara and Thomas, June 14th, 1883.

Nothing more.

He flipped it back and studied the image more closely, noting the quality of the photograph remarkably clear for its age, preserved with obvious care through generations.

It was then, as the afternoon sun shifted angle and illuminated the glass differently, that David noticed something unusual.

He reached for his magnifying glass, the one he kept on his desk for examining details in historical documents and photographs.

Leaning closer, he focused on the bride’s hands, which were clasped together at her waist in the traditional pose of brides from that era.

But there was something in her right hand.

David’s pulse quickened as he adjusted the magnifying glass, bringing the bride’s hands into sharper focus.

Between her clasped fingers, partially concealed by the folds of her dress and the angle of her hands, was a small piece of fabric.

At first glance, it might have been dismissed as part of her dress or a decorative handkerchief.

Brides often carried such items in portraits, but something about the way she held it, the deliberate positioning, the tension visible even in a century old photograph, suggested this was no ordinary accessory.

He moved to his desk and switched on the highintensity lamp he used for archival work, positioning the photograph directly beneath it.

The additional light revealed more detail.

The fabric appeared to be white or cream colored, roughly the size of a man’s pocket square, but as David examined it more closely, he could see there were markings on it.

Tiny, precise markings that looked almost like embroidery or careful stitching.

His hands trembled slightly as he reached for his phone and snapped several highresolution photos of the portrait, then transferred them to his computer.

Using photo enhancement software, he zoomed in on the bride’s hands, adjusting contrast and brightness to bring out every possible detail.

The markings became clearer.

They weren’t random decorative patterns.

They looked deliberate, systematic, almost like coordinates or symbols.

The stitching formed what appeared to be numbers and directional markers, incredibly tiny and precise.

David sat back in his chair, his mind racing.

In 1883, Louisiana was in the midst of reconstruction’s brutal aftermath.

Black communities lived under constant threat.

The rise of white supremacist violence, the systematic dismantling of civil rights gains, the terror campaigns designed to keep formerly enslaved people subjugated.

For a black bride to hide something in her wedding portrait, to carry it so carefully, so deliberately, suggested this was far more than a sentimental keepsake.

He looked at the groom’s face again at Thomas’ solemn expression.

There was something in his eyes, not fear exactly, but awareness, a gravity that went beyond wedding day nerves.

And Clara, the bride, despite her formal pose, had the slightest tension around her mouth, as if she were holding her breath, holding something back.

David knew he had stumbled onto something significant.

But what? And why would someone encode information in a wedding photograph? The questions multiplied in his mind as the afternoon light faded and shadows lengthened across his office.

The next morning, David arrived at the museum an hour early, the photograph carefully stored in an archival sleeve in his leather satchel.

He had barely slept, his mind consumed by possibilities.

Before diving deeper, he needed to understand the context.

Who Clara and Thomas were, where they lived, and what their world looked like in 1883 Louisiana.

He started with the museum’s own archives, pulling record books and city directories from New Orleans in the 1880s.

The name Thomas was common, but combined with Clara and a wedding date of June 14th, 1883, he hoped to narrow it down.

Hours passed as he scanned through handwritten entries, cross- refferencing church records, marriage licenses, and census data.

The work was painstaking, but David had learned long ago that history revealed itself slowly through patience and persistence.

By midm morning, he found a promising lead.

A marriage license registered at the Orleans Parish Courthouse.

Clara, age 24, and Thomas, age 27, married June 14th, 1883.

The license listed Thomas’s occupation as carpenter and noted they resided in the TMA neighborhood.

One of the oldest black neighborhoods in America, a community that had been free people of color even before the Civil War.

David felt a surge of excitement.

TMA had been a center of black culture, resilience, and resistance for generations.

If Clara and Thomas lived there, they would have been part of a tight-knit community that looked after its own, that kept secrets when necessary, that understood survival required more than just endurance.

It required strategy.

He pulled property records next, searching for any address associated with Thomas’s name.

He found it.

A small lot on St.

Phillip Street, purchased in 1881.

The fact that Thomas owned property just 2 years after reconstruction ended, spoke to either extraordinary fortune or extraordinary determination.

Most black families in that era rented, sharecropped, or lived in conditions barely better than slavery.

Ownership meant something.

David then turned to newspaper archives, searching for any mention of Clara or Thomas in the years surrounding their wedding.

The Times Pikune and other papers from that era rarely mentioned black citizens unless reporting crimes or reinforcing racist stereotypes.

But sometimes, if one looked carefully, there were small notices, obituaries, property transactions, church announcements.

He found nothing about Clara or Thomas directly, but he did find something else that made his breath catch.

Multiple reports throughout 1883 and 1884 of black families mysteriously disappearing from New Orleans, particularly from neighborhoods like TMA.

The articles framed these disappearances with suspicion, suggesting criminal activity or irresponsibility.

But David, reading between the lines of racist journalism, recognized another possibility entirely.

David knew he needed expert help to decipher the markings on the fabric Clara held.

He contacted Dr.

Angela Freeman, a textile historian and professor at Tulain University, who specialized in 19th century American needle work and coated fabrics.

They had collaborated on previous projects, and David trusted both her expertise and her discretion.

Angela arrived at the museum that afternoon, her enthusiasm evident the moment David showed her the enhanced photographs.

She studied them in silence for several minutes, occasionally zooming in on specific sections, her expression growing more animated with each passing moment.

David, do you know what you have here?” she finally asked, her voice barely above a whisper.

“This isn’t decorative embroidery.

These are navigational markers.

See these patterns? The way the stitches form specific angles and groupings? This is coded information.

” She pulled out her tablet and began comparing the stitching patterns to historical examples she had documented over the years.

During slavery and even after emancipation, black communities used textiles to communicate secretly.

Quilts are the most famous example.

The Underground Railroad quilts with their coded patterns.

But handkerchiefs, scarves, even dress hems were used to pass information that couldn’t be written down safely.

Angela traced her finger across the screen following the stitched lines.

These marks here, if I’m reading this correctly, these are geographic coordinates, not in the modern latitude longitude system we use today, but in a directional coding system.

See how this cluster of stitches forms what looks like a compass rose and these longer lines radiating out? Those would indicate directions and distances.

David leaned closer, his excitement building.

Directions to wear.

That’s what we need to figure out, Angela said.

But based on the complexity and the care taken to hide this in a wedding portrait, I’d guess these coordinates led to safe locations, places where people could hide, rest, or escape.

The Underground Railroad didn’t end with the Civil War.

David, the network adapted, continued during reconstruction and especially after it collapsed in 1877.

Black people still needed ways to escape violence, to find safety.

She pulled up a historical map of Louisiana on her tablet.

In 1883, this state was a powder keg.

White supremacist groups were terrorizing black communities, burning homes, lynching people who dared to vote or own property or simply exist with dignity.

The federal troops had withdrawn.

Black people were left defenseless against organized violence.

David thought about the newspaper reports of disappearing families.

So Clara was carrying a map, a way out, possibly, Angela said carefully.

Or a way to find others who had already left.

Look at this section here.

She pointed to a particularly dense area of stitching near the edge of the fabric.

This pattern repeats three times.

In textile coding, repetition often indicated emphasis.

These were important locations, places you absolutely needed to know about.

Over the following days, David immersed himself in the history of TMA during the 1880s.

What he discovered painted a picture of a community under siege, yet fiercely resilient.

The neighborhood had been a haven for free people of color since the early 1800s.

A place where black musicians, artisans, and entrepreneurs built lives of dignity and culture despite constant oppression.

But by 1883, that world was collapsing.

The gains of reconstruction, voting rights, political representation, land ownership were being systematically stripped away through violence and legal manipulation.

The Louisiana Constitution of 1879 had disenfranchised most black voters.

White supremacist organizations operated openly, attacking black families with impunity.

The message was clear.

Black people would be forced back into submission by any means necessary.

David found records of churches in TMA that had served as meeting places and centers of resistance.

St.

Augustine Catholic Church established in 1841 had been a cornerstone of the free black community.

He wondered if Clare and Thomas had been married there, if the church had played a role in whatever network the fabric coordinates represented.

He decided to visit TMA himself to walk the streets where Clara and Thomas had lived to see if any physical traces of their world remained.

On a warm Saturday morning, he drove through the neighborhood parking near St.

Philip Street.

The address from the property records no longer existed as a standalone structure.

The lot had been absorbed into a larger development decades ago, but the surrounding blocks still held buildings from the late 1800s.

Their weathered facades testaments to survival.

He walked slowly, imagining what these streets had looked like in 1883.

horsedrawn carts instead of cars, gas lamps instead of electric lights, and always the undercurrent of danger, the knowledge that violence could erupt at any moment without warning or consequence for the perpetrators.

At St.

Augustine Church, David found the parish office open.

An elderly woman named Mrs.

Delqua, a longtime parishioner and volunteer archivist, greeted him warmly when he explained his research.

Her eyes lit up when he mentioned the names Clara and Thomas and the date 1883.

We have marriage records going back to the church’s founding, she said, leading him to a small room lined with leatherbound ledgers.

Let me see what we can find.

She pulled a volume from 1883 and carefully turned the yellowed pages.

There, an elegant script was the entry, Clara, Spinster, and Thomas, Bachelor, united in holy matrimony on the 14th day of June in the year of our Lord, 1883.

But it was the notation in the margin that made David’s heart race.

witnesses, Samuel and Ruth, and next to their names in tiny script, almost invisible, conductors.

The word conductors changed everything.

David knew immediately what it meant.

Conductors were the guides who helped enslaved people escaped to freedom along the Underground Railroad.

But the Underground Railroad had officially operated before the Civil War ended in 1865.

Why would conductors still be identified in 1883, nearly two decades after emancipation? Mrs.

Deloqua saw the question in David’s eyes.

She gestured for him to sit, then settled into her own chair with the careful movements of someone who carried decades of stories.

Young man, the Underground Railroad never truly ended.

It transformed.

My grandmother told me stories.

She was born in 1879.

Lived through all of this.

After reconstruction failed, after the federal troops left and the violence came back worse than ever, black people still needed ways to escape.

She spoke quietly as if the walls themselves might be listening.

Even now, they called it different things.

the network, the chain.

Some people just called it the way through.

It wasn’t about running north anymore.

That path was known, watched, sometimes blocked.

This was about moving between safe communities, about disappearing when your name got on the wrong list, when your family was threatened, when you had no other choice.

David showed her the enhanced photographs of the wedding portrait, pointing out the fabric Clara held.

Mrs.

Deloqua studied it for a long moment, then nodded slowly.

My grandmother mentioned something like this.

She called them passage cloths.

Women carried them because women were searched less often, suspected less often.

The information was hidden in plain sight, disguised as decoration or sentiment.

“Do you know where these coordinates might have led?” David asked.

Mrs.

Deloqu stood and moved to a large map of Louisiana on the wall.

Its surface marked with pins and notes from various historical projects.

“In the 1880s, there were several communities that took people in.

Some were settlements deep in the bayou where law enforcement rarely went.

Others were farming communities further north near the Arkansas border where black families had established themselves and looked after newcomers.

And then she paused, her finger hovering over a spot near the Gulf Coast.

There were the maritime routes.

Maritime routes ships, she explained.

Black sailors, fishermen, port workers.

They moved people out through New Orleans Harbor to ports further east and north.

Mobile Pensacola, even as far as Charleston.

From there, people could start new lives, sometimes even leave the country entirely.

Some went to Mexico, to Caribbean islands, anywhere away from the violence.

David felt the pieces beginning to connect.

Clara’s fabric might have been more than just a map of land routes.

It could have included information about ships, departure times, contact names at various ports.

The repetitive pattern Angela had noticed might have indicated the most reliable routes, the ones that had successfully moved people to safety multiple times.

“What happened to Samuel and Ruth?” David asked.

the witnesses listed as conductors.

Mrs.

Delqua’s expression grew somber.

I can check our records, but she trailed off and David understood.

Conductors lived dangerous lives.

Many disappeared, were killed, or were forced to flee themselves.

Back at the museum, David and Angela worked late into the evening.

The wedding portrait displayed on a large screen alongside historical maps of Louisiana and the Gulf Coast.

They had enlisted help from Marcus, a ctography specialist who worked in the museum’s geography department.

Together, the three of them attempted to translate Clara’s stitched coordinates into actual locations.

Marcus had brought his collection of 1880s survey maps, shipping charts, and land plot records.

The challenge, he explained, is that the landmarks and measurement systems from 1883 are different from what we use now.

Rivers have changed course.

Roads have been built or abandoned.

Entire communities have vanished.

We’re essentially trying to read a map of a world that doesn’t exist anymore.

Angela had made detailed sketches of each stitched symbol on Clara’s fabric, numbering them for reference.

She laid them out in sequence.

I think this first cluster represents starting points, locations in New Orleans itself.

See how they’re grouped together and connected with shorter lines.

These would be meeting places, safe houses where people could gather before beginning a journey.

David Cross referenced the directional patterns with street layouts from 1883 TMA.

One coordinate seemed to align with the intersection near St.

Augustine Church.

Another pointed to a location near the French market where black vendors sold goods and where crowds provided cover for clandestine meetings.

A third suggested a spot along Bayou St.

John where the water could provide escape routes into the wetlands.

Now these longer lines, Angela continued pointing to the radiating stitches.

These indicate the actual escape routes.

This one heads northwest, probably following the Mississippi River.

This one goes almost due north, maybe toward Mississippi or Arkansas.

And this one, she traced a line that curves southeast.

This one goes toward the coast.

Marcus pulled up a historical shipping chart from 1883 showing ports and regular maritime routes.

If they were using ships, they’d need to know departure schedules, which docks were safe, which captains could be trusted.

Look here, there’s a notation on this chart about a regular packet service between New Orleans and mobile.

Small ships, mixed cargo, and passengers.

That would have been a perfect way to move people without attracting attention.

For hours they worked slowly building a picture of an intricate network that existed in the shadows of 1880s Louisiana.

Each coordinate Clara had carried represented not just a location but a lifeline.

Someone’s only chance at survival.

A family’s escape from violence.

A community’s determination to protect its own despite impossible odds.

As midnight approached, Marcus sat back and rubbed his tired eyes.

You realize what this means? Clara wasn’t just carrying this map for herself.

She was a conductor.

She and Thomas both probably.

This wedding portrait wasn’t just a personal keepsake.

It was an insurance policy, a way to preserve critical information in case the original documents were discovered or destroyed.

David looked at Clara’s face in the portrait, seeing her now with complete new understanding.

This young woman, barely into her 20s, had risked everything.

Simply possessing this information could have gotten her killed.

David knew he needed to find out what happened to Clara and Thomas after their wedding.

Did they continue their work as conductors? Did they survive the violent decades that followed? He returned to the archives with renewed purpose, searching death records, property transfers, census data, anything that might tell him their story’s conclusion.

He found Thomas first in a property record from 1891.

The St.

Phillip Street lot had been transferred to Clara’s name alone with a notation, widow.

David’s chest tightened.

Thomas had died sometime between 1883 and 1891, when he would have been only in his mid-30s.

David searched death certificates from that period, finding Thomas’s entry dated March 1889.

Cause of death, injuries sustained.

No details, no elaboration, just those two words, which in 1889, Louisiana, for a black man involved in helping people escape white supremacist violence, could mean anything.

An accident, an altercation.

The euphemistic language white authorities used to avoid investigating crimes against black victims.

David sat in the silent archive room, feeling the weight of Thomas’s story settle over him.

This man, who had stood so dignified in his wedding portrait, who had supported his wife’s dangerous work, who had built a life against impossible odds, had been reduced to two words in an official record.

But Clara’s story continued.

David found her listed in the 1900 census, still living on St.

Phillip Street, her occupation listed as seamstress.

The entry showed she lived alone, no children recorded.

He found her again in the 1910 census.

now 60 years old, still working, still in TMA.

Then he found something that made everything suddenly painfully clear.

In a collection of oral histories recorded in the 1930s by the Federal Writers Project, a depression era program that documented stories from formerly enslaved people and their descendants, there was an interview with an elderly woman identified only as CR, aged 80, New Orleans.

The interviewer’s notes described her as a dignified woman, reluctant to speak in detail about past events.

But the fragment she did share painted a vivid picture.

She spoke of helping families find their way after her husband’s death.

She mentioned sewing special pieces that women could carry.

She talked about the fear, the constant vigilance, the way she had to hide what was most important in plain sight.

The interview was brief, barely two pages, but one passage struck David with particular force.

They took my Thomas for helping people get to safety.

Said he was causing trouble interfering with the natural order.

But we knew the truth.

Freedom didn’t end with the war.

It had to be fought for every single day in small ways and dangerous ways.

The cloth I carried on my wedding day was my promise to him, to our people, to anyone who needed a way out.

I kept that promise long after he was gone.

David sat motionless, the interview transcript in his hands.

Clara had continued the work after Thomas’s murder.

She had carried on alone for decades, using her skills as a seamstress to create and distribute passage cloths, to keep the network alive, to ensure that others might escape the violence that had taken her husband.

David knew he had to find Clara’s descendants, if any, existed.

Someone needed to know her story to understand what she had sacrificed and achieved.

He started with property records, tracing ownership of the St.

Phillip Street lot forward through the decades.

Clara had held on to the property until her death in 1932 at age 73.

The lot had then been transferred to a woman named Rose, identified in the deed as Clara’s niece.

Following that thread forward, David eventually made contact with Patricia, a 72-year-old woman living in the Gentilly neighborhood of New Orleans.

She was Rose’s granddaughter, which made her Clara’s great great niece.

When David called and explained his research, there was a long pause on the other end of the line.

“You found Aunt Clara’s wedding picture?” Patricia finally said, her voice thick with emotion.

“We thought all of that was lost in Katrina.

” They met the following afternoon at Patricia’s home, a modest house filled with family photographs and memorabilia.

Patricia moved slowly due to arthritis, but her mind was sharp and her memory full of stories passed down through generations.

She brought out a worn shoe box filled with documents, letters, certificates, a few photographs.

My grandmother Rose told me about Clara when I was a girl, Patricia said, handling the documents with reverence.

She said Aunt Clara was the bravest woman she’d ever known, that she’d helped people in ways that couldn’t be talked about openly, even decades later.

But so much of the detail was lost.

People were afraid to write things down, afraid to say too much.

David showed her the wedding portrait and the enhanced images of the fabric Clara held.

Patricia stared at them for a long moment, then began to cry quietly.

She was so young, just a young woman, and she took on all that danger, all that responsibility.

From the shoe box, Patricia pulled a small piece of fabric, yellowed with age and fragile to the touch.

Grandmother Rose said Clara gave her this before she died.

Said it was important, that it should be kept safe, but that she’d know when the time was right to share it.

The fabric was larger than the piece in the wedding portrait, perhaps 8 in square, and covered entirely with the same kind of tiny, precise stitching.

David’s hands trembled as he held it up to the light.

This was another passage cloth, possibly one of the last Clara had made.

There’s something else, Patricia said.

She pulled out a small leather journal, its cover cracked and worn.

This was Clara’s.

Grandmother Rose hid it away for decades.

I’ve read it, but I never understood all of it.

Maybe it will make more sense to you.

The journal was Clara’s daily record from 1889 to 1920, written in careful script.

Most entries were brief, weather, work completed, visitors received, but scattered throughout were coded references that David now understood.

Helped three packages move north.

New route established to the eastern dock lost two travelers to the red shadows.

And this last phrase clearly referring to people caught by white supremacist violence.

One entry from June 14th, 1920, her 61st birthday and the 37th anniversary of her wedding read simply, “Thomas, I kept my promise.

The way through remains open.

You’re Clara.

” 3 months after discovering Clara’s wedding portrait, David stood in the museum’s main gallery where a new exhibition had just opened.

threads through time, the hidden networks of resistance in postreonstruction Louisiana.

The wedding portrait held pride of place displayed alongside the passage cloths, the Clara’s journal, and the maps showing the roots she had helped maintain for over 40 years.

Patricia had agreed to loan the family materials, understanding their historical importance.

She stood beside David now, looking at the portrait of her great great aunt, with pride and sorrow mingled in her expression.

She deserved to have her story told, Patricia said quietly.

All of them did.

Thomas, the people they helped, the network that kept fighting long after the history books said the fight was over.

The exhibition attracted significant attention from historians, journalists, and community members.

Many visitors were descendants of TMA families, and some recognized names or places in the documentation.

An elderly man named Jerome approached David one afternoon, pointing to one of the decoded coordinates on the wall map.

That location, Jerome said, that was my great-grandfather’s farm up near the Arkansas border.

family stories.

Always said he took people in, helped them get settled, but we never had proof.

He died in 1894, never talked about it openly.

He paused, his eyes glistening.

Thank you for showing that he mattered, that what they did mattered.

David had worked with Angela to create an educational component for the exhibition, explaining the textile coding techniques and the broader historical context.

School groups visited regularly and David noticed how students, particularly young black students, stood transfixed before Clara’s portrait, seeing perhaps for the first time a reflection of resistance that looked like them that came from their own communities.

One afternoon, a teenage girl named Jasmine asked David a question that stayed with him.

Why did Clara keep doing it after Thomas died? Wasn’t she scared? David thought carefully before responding.

She was probably terrified every single day, but she understood something important.

that freedom isn’t just about laws or declarations.

It’s about people choosing to help each other survive, to create paths forward, even when everything seems hopeless.

Her fear was real, but her commitment to her community was stronger.

The museum began receiving inquiries from other institutions, wanting to study the passage cloths to understand how the post-reonstruction networks operated.

David found himself coordinating with researchers across the country.

Each discovery adding new layers to Clara’s story and the broader history of black resistance in the late 19th century.

On the anniversary of Clara and Thomas’ wedding, June 14th, 2025, the museum held a special commemoration.

Patricia’s entire extended family attended, including relatives who had traveled from other states.

They stood together before the portrait, seeing Clara and Thomas, not just as historical figures, but as family, as ancestors whose courage had helped ensure their own existence.

As the day ended and the gallery emptied, David stood alone before the wedding portrait.

Clara gazed back at him across 142 years.

Her hand still holding that small piece of fabric, that tiny map to freedom.

What had seemed at first like a simple wedding photograph had revealed itself to be so much more.

A document of resistance, a testament to courage, a reminder that the fight for dignity and justice never truly ends.

It simply transforms, carried forward by ordinary people making extraordinary choices.

The portrait would remain here, David knew, telling its story to future generations, ensuring that Clara and Thomas and the countless unnamed people they helped would not be forgotten.

The threads Clara had stitched so carefully in 1883 now connected past to present, weaving a narrative of survival, resilience, and the quiet heroism of those who risk everything so others might be

News

🚛 HIGHWAY CHAOS — TRUCKERS’ REVOLT PARALYZES EVERY LAND ROUTE, KHAMENEI SCRAMBLES TO CONTAIN THE FURY 🌪️ The narrator’s voice drops to a biting whisper as convoys snake through empty highways, fuel depots go silent, and leaders in Tehran realize this isn’t just a protest — it’s a nationwide blockade that could topple power and ignite panic across the region 👇

The Reckoning of the Highways: A Nation on the Edge In the heart of Tehran, the air was thick with…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Darkened City: A Night of Reckoning In the heart of Moscow, a city that once stood proud and unyielding,…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Shocking Resurrection: A Hollywood Revelation In a world where faith intertwines with fame, the announcement sent ripples through the…

🎬 “TO THIS DAY, NO ONE CAN EXPLAIN IT” — JIM CAVIEZEL BREAKS YEARS OF SILENCE ABOUT THE MYSTERY THAT HAUNTED HIM AFTER FILMING ⚡ In a hushed, almost trembling confession, the actor leans back and stares past the lights, hinting at strange accidents, eerie coincidences, and moments on set that felt less like cinema and more like something watching from the shadows, leaving even hardened crew members shaken to their core 👇

The Unseen Shadows: Jim Caviezel’s Revelation In the dim light of a secluded room, Jim Caviezel sat across from the…

📜 SEALED FOR CENTURIES — ETHIOPIAN MONKS FINALLY RELEASE A TRANSLATED RESURRECTION PASSAGE, AND SCHOLARS SAY “NOTHING WILL BE THE SAME” ⛪ The narrator’s voice drops to a breathless whisper as ancient parchment cracks open under candlelight, hooded figures guard the doors, and words once locked inside stone monasteries spill out, threatening to shake faith, history, and everything believers thought they understood 👇

The Unveiling of Truth: A Resurrection of Belief In the heart of Ethiopia, where the ancient echoes of faith intertwine…

🕯️ FINAL CONFESSION — BEFORE HE DIES, MEL GIBSON CLAIMS TO REVEAL JESUS’ “MISSING WORDS,” AND BELIEVERS ARE STUNNED INTO SILENCE 📜 The narrator’s voice drops to a hushed, dramatic whisper as old notebooks open, candlelight flickers across ancient pages, and Gibson hints that lines never recorded in scripture could rewrite everything the faithful thought they knew 👇

The Unveiling of Hidden Truths In the dim light of his private study, Mel Gibson sat surrounded by piles of…

End of content

No more pages to load