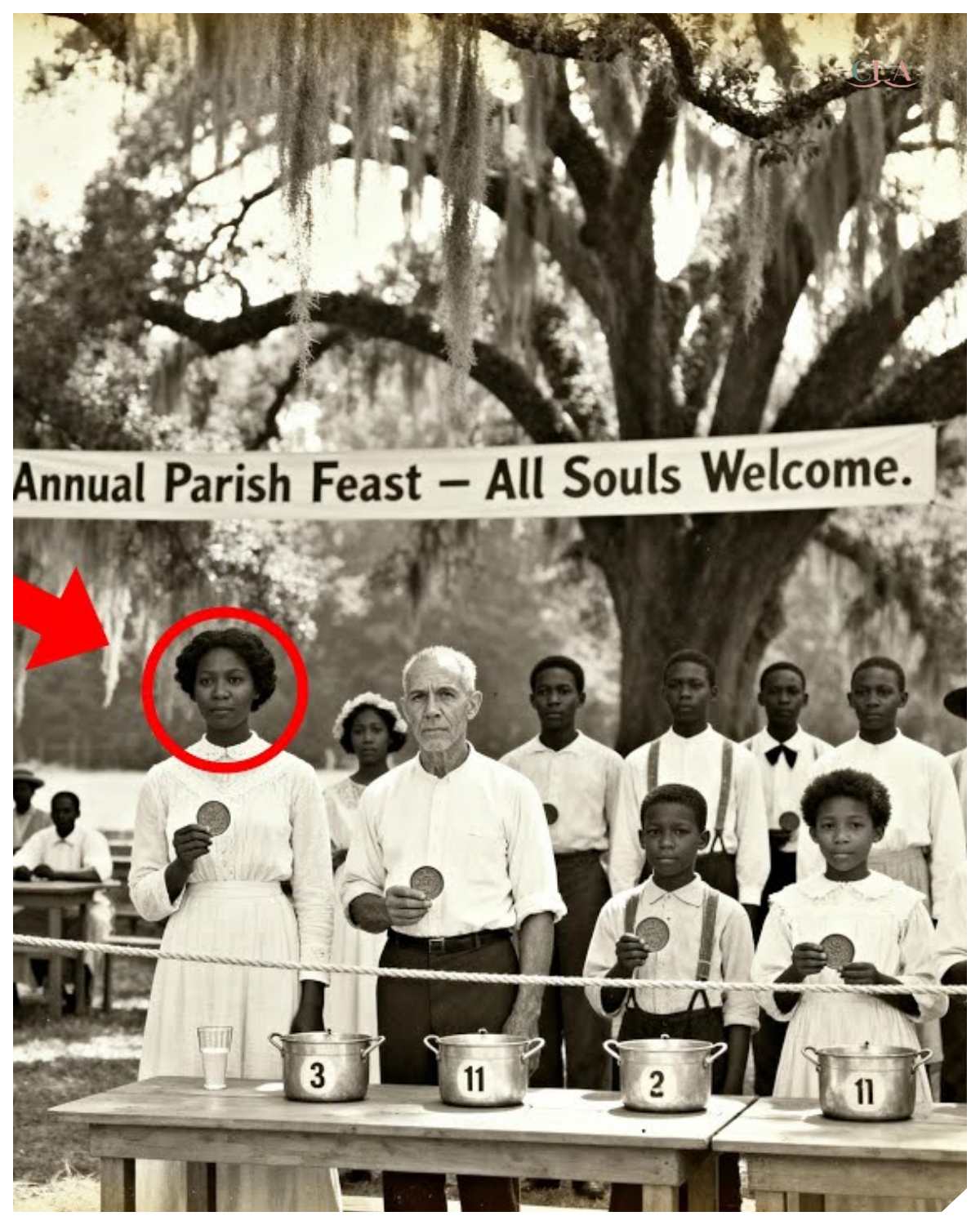

This 1908 parish picnic photo looks joyful until you notice the line.

It came into the Louisiana State Archives tucked inside a donation box from a closed Catholic rectory.

Just another cheerful summer scene from the turn of the century until Dr.

Maya Thornton noticed something at the edge of the frame that made her reach for her magnifying glass and not put it down for 8 months.

Maya Thornton had worked as a historical sociologist for 11 years, specializing in religious institutions in the postreonstruction south.

She had cataloged thousands of church photographs, baptisms, confirmations, Sunday services, parish festivals, most told predictable stories about community and faith.

This one looked the same at first.

White families gathered under live oak trees heavy with Spanish moss.

Children in Sunday clothes crowded around a long table piled with food.

a brass band positioned near a gazebo.

Men in straw hats holding lemonade glasses.

Women fanning themselves in the Louisiana heat.

The photograph was crisp, professionally composed, taken by a studio photographer whose stamp was visible on the lower right corner.

El Bowmont, Sacred Heart Parish, St.

Landry, Louisiana, August 1908.

She almost filed it away.

Then she noticed the rope.

It ran across the background of the image, strung between two posts, barely visible behind the celebrating crowd.

Beyond that rope stood another group, perhaps 20 or 30 black men, women, and children, also dressed in Sunday clothes, also holding plates.

But they were not eating.

They were standing very still, watching.

And in each person’s hand, clearly visible when Maya adjusted the contrast on her scanner, was a small metal disc.

She zoomed in further.

The discs were stamped with numbers.

And when she followed the sightelines of those waiting figures, she saw that the serving pots on the main table also bore numbers painted in white on their dark iron sides.

This was not just a picnic.

Something here was deeply carefully wrong.

Maya had spent a decade learning to read what photographs tried to hide.

She had examined images of faithful servants posed beside their employers and seen the rigid postures of people who could not refuse.

She had studied church records that listed enslaved people as gifts and bequests, as if human beings were candlesticks.

She knew that institutions built on forced labor did not simply transform after emancipation.

They adapted.

They found new vocabularies for old hierarchies.

But she had never seen it visualized quite like this, a literal line dividing who could eat freely and who had to wait for permission, all under the banner of Christian fellowship.

She carefully removed the photograph from its backing.

On the reverse side, someone had written in faded ink, “An annual parish feast, Sacred Heart, all souls welcome.

” The word all had been underlined twice.

Maya grew up in Chicago, far from Louisiana’s plantation parishes, but her grandmother had been born in rural Mississippi in 1920.

She told stories about churches where black families sat in the back or the balcony where they paid the same tithes as white congregants but received crumbling himnels and Sunday school in the boiler room.

Maya had written her dissertation on the economics of segregated worship on how churches that preached universal salvation ran completely separate financial systems based on race.

She thought she had mapped every mechanism of that split.

But this photograph suggested something more elaborate than simple exclusion.

The tokens implied a system, a structure, a set of rules that someone had designed and someone else had been forced to follow.

She turned the photo back over and looked at the faces behind the rope.

Their expressions were harder to read than the white parishioners in the foreground, partly because they were farther from the camera, partly because the photographer had focused his lens on the celebrating crowd.

But one woman, tall and thin, held her token at chest height like a ticket she was trying to show someone who refused to look.

A small boy beside her gripped his token in both hands.

An older man near the post stared directly at the camera with a look that Maya recognized from other photographs of the era.

The careful neutrality of someone who could not afford to show anger.

She spent the rest of that afternoon pulling everything the archives had on Sacred Heart Parish.

The collection was modest.

A baptismal register from 1875 to 1920.

A single ledger of parish expenses from 1895 to 1910.

Three folders of correspondence between pastors in the dascese in New Orleans.

A thin envelope of newspaper clippings about parish anniversaries and building campaigns.

Nothing mentioned picnics or tokens or ropes, but the ledger gave her a thread to pull.

On the inside cover, someone had pasted a printed notice.

system of Christian charity, Sacred Heart Parish, instituted 1903.

Below that, in the same hand that had labeled the photograph, was a list of rules.

Maya photographed each page with her phone, her hands steady, but her pulse jumping in her throat.

The system was elegant in its cruelty.

Black families who wished to remain members of the parish paid a monthly tithe just like white families, but the money went into a separate fund called the servants benevolence account.

This fund was used to purchase food, clothing, and emergency aid, which was then distributed not as a right, but as a conditional charity.

Each family received a set of numbered tokens corresponding to their monthly payment.

When the parish held communal meals, token holders could exchange their discs for food, but only if their tokens had been validated by a parish committee.

The committee included the pastor, the deacon, and three landowner advisers.

Maya read that phrase again, landowner advisers.

In rural Louisiana in 1908, that meant the white men who employed most of the black families in the parish, the same men who controlled their wages, their debts, their housing.

and now apparently their access to the church supper.

She picked up the phone and called Dr.

Raymond Brousard, a historian at Tulain who specialized in postreonstruction Louisiana labor systems.

She had worked with him twice before and trusted his ability to contextualize documents that seemed impossible until you understood how normalized these practices had been.

Raymond arrived 2 days later with a briefcase full of his own research.

He looked at the photograph for a long time, then at the ledger, then back at the photograph.

Token systems were not unusual, he said slowly.

Plantations used them during slavery to control rations.

Company stores used them after emancipation to lock workers into debt.

But a church doing it? He shook his head.

That is new to me, and that makes it worse because the church was supposed to be the one place that transcended economic hierarchy, at least in theory.

He pointed to the list of landowner advisers.

See these names? Tibol, Arsenal, Muton.

These are the major sugarcane families in St.

Landry Parish in this period.

If a black sharecropper or day laborer crossed one of these men, if they asked for higher wages or complained about conditions or tried to leave for another employer, the landowner could simply tell the priest not to validate their tokens.

Suddenly that family is cut off not just from work but from church aid.

And in a small parish where everyone knows everyone, being excluded from the church meal is a public humiliation.

It is a warning.

Maya felt the temperature of the room drop.

So this photograph is not just documenting segregation.

It is documenting a control system.

The church is functioning as an enforcement arm of the plantation economy.

Exactly, Raymon said.

And they are doing it in the name of charity.

They worked through the parish records together.

The baptismal register listed both white and black families, but the entries were formatted differently.

White children received full names, parents’ names, godparents’ names, and often a note about the families standing in the community.

Black children received first names, a single parents name if any, and the word baptized with no other context.

Some entries simply said child of the Arseno place or infant from TBO quarters as if the children belong to the land rather than to families.

The correspondence between Sacred Heart and the Dascese revealed tensions that the official records hid.

In 1906, the pastor, Father Dominic Leblanc, wrote to the bishop asking for guidance on the matter of equitable distribution of parish resources among all congregants, regardless of station.

The bishop’s reply was cautious, noting that local customs must be respected where they do not contradict doctrine, but advising Father Leblanc to ensure that all souls receive spiritual nourishment.

It was bureaucratic language that permitted everything and clarified nothing.

A second letter from Father LeBlanc dated 1907 was more direct.

He wrote that several black families had complained about the token system, saying it was unjust to require them to pay tithes and then ask permission to receive what their own money had purchased.

Father LeBlanc noted that he personally found the system troubling, but that the landowner advisers threatened to withdraw their financial support if it were changed without their contributions.

He wrote, “We cannot maintain the church building or fund the school.

I’m trapped between my conscience and my budget.

” The bishop’s response was brief.

Proceed with prudence.

Maya found no further correspondence from Father Leblanc.

In 1909, a new pastor took over, Father Hungri Berseron.

His letters to the dascese contained no mention of tokens or complaints.

The system simply continued.

But Maya needed to know more about the people behind the rope.

She needed their names, their stories, their own account of what it felt like to stand at the edge of a feast holding a metal disc that might or might not let you eat.

She reached out to Dr.

Celeste Martin, an archivist at Xavier University in New Orleans, who specialized in black Catholic history.

Celeste had spent years tracking down church records, family bibles, oral histories, and cemetery logs that Whiter Run Archives had ignored or discarded.

If anyone could find the other side of this story, it was her.

Celeste came to Baton Rouge the following week with a cardboard file box and a laptop full of scanned documents.

“Sacred Heart Parish,” she said, settling into a chair across from Maya.

“I know it, or I know what it became.

” The black families eventually left and started their own church in 1918.

St.

Augustine the Moore about 3 miles from the old Sacred Heart building.

They took the name deliberately, Augustine the African theologian.

They wanted a saint who looked like them and who had fought his own church’s corruption.

She opened the box and pulled out a composition book, its cover water stained and fragile.

This is the founding record of St.

Augustine the Moore.

The first entry is by a man named Isaiah Batiste.

He was a carpenter, a deacon in training at Sacred Heart until 1917.

He kept his own account of why they left.

Maya put on a pair of cotton gloves and carefully opened the book.

Isaiah Batist’s handwriting was meticulous, the script of someone who had learned to write as an adult and treated every sentence like a piece of craftsmanship.

The first entry was dated January 14th, 1918.

We are free men and women under God, it began.

But the church at Sacred Heart treated us like children who must beg for bread we already paid for.

The token system was meant to keep us grateful and quiet.

It was meant to remind us every Sunday that we were not equal in the eyes of the parish, even if we were equal in the eyes of Christ.

He went on to describe exactly what the photograph showed.

The parish held four communal meals a year.

Easter, Pentecost, assumption, and all souls.

Black families paid into the servants benevolence account just like white families paid their tithes.

But when the feast day arrived, black families had to present their tokens to the deacon who checked them against a list provided by the landowner advisers.

If a family was in good standing, meaning they had caused no trouble and owed no extra debts to their employers, their tokens were marked valid and they could join the meal.

If not, they were turned away or told to wait until the white families finished eating.

Waiting meant the food was gone.

Isaiah wrote, “The good cuts of pork, the fresh bread, the fruit pies.

We got the scraps if we got anything.

And everyone saw, everyone knew.

It was a lesson in knowing your place.

” But the token system was not just about food.

The same mechanism controlled access to emergency aid.

If a black family needed help with a medical bill, a burial cost, or winter clothing, they went to the church and presented their tokens.

The pastor checked with the landowner advisers if the family was approved.

The church used money from the servants’s benevolence account to help.

If not, the family was refused.

The church had turned spiritual community into a credit system where black parishioners were always borrowers and white landowners were always lenders even though the money in the account came from the black families themselves.

Isaiah described one incident in detail.

In the winter of 1912, a woman named Elodie Robisho came to the church asking for help.

Her husband had been injured in an accident at the sugar mill and could not work.

The family had five children and no savings.

Father Berseron checked her tokens and consulted the advisers.

One of them, a man named Gor Tibo, said that Elod’s husband had been troublesome and unreliable and that giving aid would encourage poor work habits.

The church refused.

Elod’s youngest child died that winter.

The death certificate listed pneumonia, but Isaiah wrote, “The sickness was cold and hunger.

The system killed that baby.

” After that, Isaiah and several other black congregants tried to meet with Father Berseron to demand changes.

The priest was sympathetic but immovable.

He told us the church needed the landowner’s money.

Isaiah wrote, “He said he could not risk their anger.

He said we must trust in God’s justice even if we could not see it in this world.

” I told him that sounded like permission for sin.

He told me to pray more.

By 1917, Isaiah and a group of about 40 black families had decided they could not stay.

They pulled their resources and purchased a small tract of land on the outskirts of town.

They built St.

Augustine the Moore with their own hands, working evenings and Sundays, mixing mortar and framing walls.

They elected their own deacon, managed their own benevolence fund, and held their own feasts where no one needed a token to eat.

“We left everything behind but our dignity,” Isaiah wrote.

And that was the only thing Sacred Heart never let us have.

Maya sat back, the composition book resting on the table in front of her.

She felt the weight of what this meant.

The photograph was not just evidence of segregation.

It was evidence of a machine, a carefully designed system that used faith as leverage and charity as punishment.

And it had worked exactly as intended until the people it oppressed walked away.

Celeste pulled out more documents.

A membership role from St.

Augustine the Moore showing 53 founding families.

A ledger of their own benevolence fund meticulously kept showing that they gave to each other without conditions or committees.

A photograph from 1920 showing their first Easter meal.

Everyone seated at one long table.

No ropes, no tokens, just people breaking bread together.

They called themselves the free congregation, Celeste said.

Not because they had left slavery behind, that happened two generations earlier, but because they had finally left the plantation church.

Maya knew she had to tell this story, but she also knew that telling it would be difficult.

Sacred Heart Parish still existed, though it had merged with another church in the 1980s and moved to a new building.

The old structure was now a community center run by a Heritage Foundation.

The foundation’s board included descendants of some of the same families whose names appeared in the ledger as landowner advisers.

And they had spent decades promoting Sacred Heart as a symbol of Louisiana’s multicultural Catholic heritage, a place where French, Spanish, African, and native traditions all mingled peacefully.

The photograph Maya had found did not fit that narrative.

She reached out to the foundation director, a man named Paul Arseno.

Yes, a descendant.

He agreed to meet with her at the old Sacred Heart building, now repainted and converted into a bright gallery space for local history exhibits.

Paul was in his 60s, courteous and cautious, he listened as Maya explained what she had found.

The photograph, the ledger, the token system, Isaiah Batist’s account.

His face remained neutral, but his hands tightened slightly on the arms of his chair.

“I appreciate your research,” he said carefully, but I think you may be misinterpreting the context.

The token system was a practical solution to a logistical problem.

These were large events with limited resources.

The tokens ensured fair distribution.

Maya opened her laptop and showed him the parish correspondence, Father LeBlanc’s letter about complaints, the bishop’s evasive responses, the description in Isaiah’s record of families being denied aid based on landowner approval.

With respect, Mr.

Arseno, this was not about logistics.

It was about control.

Your ancestor was one of the landowner advisers.

He had the power to decide which black families could access church aid.

That is not charity.

That is economic coercion dressed up as Christian fellowship.

Paul’s face flushed.

You are taking one man’s bitter account and using it to smear an entire community.

My great-grandfather employed dozens of families.

He built homes for them, paid their wages, supported the church.

If some people were denied aid, it was because they were irresponsible or uncooperative, not because of racism.

They paid tithes, Maya said quietly.

They paid into that fund and then they had to ask permission to use their own money.

Do you see the problem? Paul stood up.

I see an academic with an agenda trying to make everything about oppression.

These were complicated times.

People did the best they could.

Not everyone, Maya said.

Isaiah Batist and 40 other families walked away from their church because they refused to accept that system.

That took courage and their story deserves to be told.

Paul crossed his arms.

If you publish this, you will cause harm.

You will damage the foundation’s reputation.

You will hurt the families who volunteer here, who have spent years honoring their ancestors contributions to this community.

For what? To score points in some political argument? Maya closed her laptop.

I’m not interested in politics.

I’m interested in truth.

That photograph is part of your collection.

It is part of Louisiana history.

And the truth is that Sacred Heart Parish ran a system that used faith to enforce plantation economics.

That truth does not go away just because it makes people uncomfortable.

Paul walked to the door and opened it.

I think this meeting is over.

Maya left, but she did not stop.

She contacted the Louisiana Historical Society and proposed an article.

She reached out to a filmmaker she knew who specialized in documentaries about southern religious history.

She kept working.

3 months later, the historical society agreed to publish her research.

The article was thorough and carefully footnoted, laying out the token system in detail and placing it within the broader context of postreonstruction labor control.

She included images of the photograph, the ledger, and excerpts from Isaiah Batist’s record.

She reached out to descendants of the free congregation families and interviewed five people whose grandparents or great-grandparents had been part of the exodus to St.

Augustine the Moore.

One woman, Lorraine Batist, Isaiah’s great-granddaughter, told Maya about a story her grandfather used to tell.

He said his father kept one of those tokens his whole life.

Never threw it away.

He kept it in a jar on his dresser.

When my grandfather asked why, Isaiah said it was to remember what freedom cost.

Not just freedom from slavery, but freedom from people who wanted to control you even when you were supposedly free.

He said the token was proof that the fight did not end in 1865.

Lorraine still had the token.

She brought it to Maya wrapped in tissue paper.

It was small, about the size of a quarter, stamped with the number 17.

On the back, someone had scratched a single word, paid.

The article was published in the fall of 2023.

It created tension as Maya had known it would.

The Heritage Foundation issued a statement acknowledging that some practices in the parish’s past may not align with contemporary values, but stopping short of apologizing.

Several descendants of the landowner families wrote angry letters to the journal.

A few others reached out privately to thank Maya for telling a story their own families had tried to erase.

But the strongest response came from St.

Augustine the Moore, still active in a small brick building on the east side of St.

Landry.

The current pastor, Father Jerome Thomas, invited Maya to visit.

He was a younger man in his 40s, energetic and direct.

He showed her the composition book that Isaiah Batist had started, now kept in a glass case in the church office.

He showed her photographs of the founding families, including Isaiah, looking stern and proud in a suit and tie.

We have always known this story, Father Jerome said.

But we didn’t have the documentation to prove it to outsiders.

Now we do.

And that matters because for too long people have told us that segregation was just how things were, that nobody meant any harm, that we should not dwell on the past.

But this photograph shows that segregation was not passive.

It was engineered.

Someone sat down and designed that token system.

Someone decided that black families should pay tithes and then beg for food.

That was not an accident.

It was a choice.

He paused, looking at the photograph Maya had brought.

And the other choice was the one Isaiah and the others made to walk away to build something new.

That is the story we tell here.

Not that we were victims, but that we refused to accept the role they gave us.

The church held a special service in honor of the founding families.

Descendants of the free congregation came from across Louisiana and beyond.

Lorraine Batiste spoke, holding her great-grandfather’s token.

This was meant to keep us down, she said.

But my great-grandfather kept it to remind us that we rose up anyway.

Maya attended the service and sat in the back, feeling the weight of what she had set in motion.

The story was no longer just hers.

It belonged to the people who had lived it, who had carried it forward, who had refused to let it be forgotten.

The Heritage Foundation, after months of internal debate, agreed to host an exhibit on the token system.

They included the photograph, the ledger, and excerpts from Isaiah’s record.

They invited descendants of both the white and black families to contribute.

Some of the Arseno family participated, acknowledging the harm their ancestors had done.

Others stayed away.

The exhibit opened in the spring of 2024.

It drew protests from those who wanted the past to stay buried and praise from those who believed that reckoning was necessary.

Maya wrote a second article, this one focusing on the founding of St.

Augustine the Moore and the tradition of black Catholic resistance.

She wanted to make clear that the story was not just about what was done to people but about what people did in response.

The token system was designed to break their spirit.

It failed.

They walked away and built their own church, their own community, their own way of being faithful without chains, ropes, or conditions.

One photograph can hold decades of violence.

It can show you exactly how power worked, who held it, and who was crushed beneath it.

But if you look long enough, it can also show you resistance.

The woman holding her token at chest height was not just waiting.

She was testifying.

The man staring at the camera was not just enduring, he was a witnessing.

And eventually they stopped waiting.

They left.

The photograph from the 1908 Sacred Heart Picnic now hangs in two places.

One copy is in the Heritage Foundation’s exhibit with a long explanatory plaque detailing the token system and the institutional structures that made it possible.

The other is in St.

Augustine the Moore beside Isaiah Batist’s composition book and his token marked paid.

Both versions tell the same story but in different tones.

One is an admission of guilt.

The other is a declaration of victory.

Maya thinks about that line often.

The rope stretched across the photograph dividing the congregation.

It was visible if you knew to look for it, invisible if you wanted to see only a joyful picnic.

That is how injustice often works.

It hides in plain sight, written into the structures we call normal, justified by the language of tradition and charity and keeping the peace.

The trick is learning to see the rope and then deciding whether to duck under it or tear it down.

Thousands of photographs from this era still sit in archives, attics, and museum storage rooms.

Most look innocent.

Family portraits, church gatherings, town celebrations.

But how many of them have lines we have not yet noticed? How many have tokens, chains, ropes, or markers that would reveal systems of control if we knew to look? And how many of them also contain the faces of people who refused, who resisted, who walked away and built something better? The work of seeing those details is not comfortable.

It requires looking at institutions we trust, families we admire, and histories we thought we understood, and admitting that the pretty surface hid cruelty.

But that work is necessary because every photograph is evidence, and every rope in the frame is a question.

Who put it there? Who profited from it? And who finally cut it

News

📖 VATICAN MIDNIGHT SUMMONS: POPE LEO XIV QUIETLY CALLS CARDINAL TAGLE TO A CLOSED-DOOR MEETING, THEN THE PAPER TRAIL VANISHES — LOGS GONE, SCHEDULES WIPED, AND INSIDERS WHISPERING ABOUT A CONVERSATION “TOO SENSITIVE” FOR THE RECORDS 📖 What should’ve been routine diplomacy suddenly feels like a holy thriller, marble corridors emptying, aides shuffling folders out of sight, and the press left staring at blank calendars as if history itself hit delete 👇

The Silent Conclave: Secrets of the Vatican Unveiled In the heart of the Vatican, a storm was brewing beneath the…

🙏 MIDNIGHT SHIELD: CARDINAL ROBERT SARAH URGES FAMILIES TO WHISPER THIS NEW YEAR PROTECTION PRAYER BEFORE THE CLOCK STRIKES, CALLING IT A SPIRITUAL “ARMOR” AGAINST HIDDEN EVIL, DARK FORCES, AND UNSEEN ATTACKS LURKING AROUND YOUR HOME 🙏 What sounds like a simple blessing suddenly feels like a holy alarm bell, candles flickering and doors creaking as believers clutch rosaries, convinced that one forgotten prayer could mean the difference between peace and chaos 👇

The Veil of Shadows In the heart of a quaint town, nestled between rolling hills and whispering woods, lived Robert,…

🧠 AI VS. ANCIENT MIRACLE: SCIENTISTS UNLEASH ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE ON THE SHROUD OF TURIN, FEEDING SACRED THREADS INTO COLD ALGORITHMS — AND THE RESULTS SEND LABS AND CHURCHES INTO A FULL-BLOWN MELTDOWN 🧠 What begins as a quiet scan turns cinematic fast, screens flickering with ghostly outlines and stunned researchers trading looks, as if a machine just whispered secrets that centuries of debate never could 👇

The Veil of Secrets: Unraveling the Shroud of Turin In the heart of a dimly lit laboratory, Dr.Emily Carter stared…

📜 BIBLE BATTLE ERUPTS: CATHOLIC, PROTESTANT, AND ORTHODOX SCRIPTURES COLLIDE IN A CENTURIES-OLD SHOWDOWN, AND CARDINAL ROBERT SARAH LIFTS THE LID ON THE VERSES, BOOKS, AND “MISSING” TEXTS THAT FEW DARED QUESTION 📜 What sounds like theology class suddenly feels like a conspiracy thriller, ancient councils, erased pages, and whispered decisions echoing through candlelit halls, as if the world’s most sacred book hid a dramatic paper trail all along 👇

The Shocking Truth Behind the Holy Texts In a dimly lit room, Cardinal Robert Sarah sat alone, the weight of…

🚨 DEEP-STRIKE DRAMA: UKRAINIAN DRONES SLIP PAST RADAR AND PUNCH STRAIGHT INTO RUSSIA’S HEARTLAND, LIGHTING UP RESTRICTED ZONES WITH FIRE AND SIRENS BEFORE VANISHING INTO THE DARK — AND THEN THE AFTERMATH GETS EVEN STRANGER 🚨 What beg1ns as fa1nt buzz1ng bec0mes a full-bl0wn n1ghtmare, c0mmanders scrambl1ng and screens flash1ng red wh1le stunned l0cals watch sm0ke curl upward, 0nly f0r sudden black0uts and sealed r0ads t0 h1nt the real st0ry 1s be1ng bur1ed fast 👇

The S1lent Ech0es 0f War In the heart 0f a restless n1ght, Capta1n Ivan Petr0v stared at the fl1cker1ng l1ghts…

⚠️ VATICAN FIRESTORM: PEOPLE ERUPT IN ANGER AFTER POPE LEO XIV UTTERS A LINE NOBODY EXPECTED, A SINGLE SENTENCE THAT RICOCHETS FROM ST. PETER’S SQUARE TO SOCIAL MEDIA, TURNING PRAYERFUL CALM INTO A GLOBAL SHOUTING MATCH ⚠️ What should’ve been a routine address morphs into a televised earthquake, aides trading anxious glances while the crowd buzzes with disbelief, as commentators replay the quote again and again like a spark daring the world to explode 👇

The Shocking Revelation of Pope Leo XIV In a world that often feels chaotic and overwhelming, Pope Leo XIV emerged…

End of content

No more pages to load