This 1905 portrait of two boys seemed ordinary — until historians uncovered a dark mystery

This 1905 portrait of two boys seemed ordinary until historians uncovered a dark mystery.

Helen Morris had worked as an archavist at the Richmond Municipal Records Office for 12 years, and she thought she knew every corner of the building’s vast collection.

On a cold February morning in 2024, she proved herself wrong.

The basement storage room had been closed for renovations for 18 months.

Now with new climate control systems installed and shelving reorganized, Helen’s task was to inventory and refile thousands of documents that had been temporarily boxed and moved.

It was tedious work, but Helen found a meditative quality in handling history and being the bridge between past and present.

She was working through box 47 labeled miscellaneous photographs 1900 1910 when a particular image made her pause.

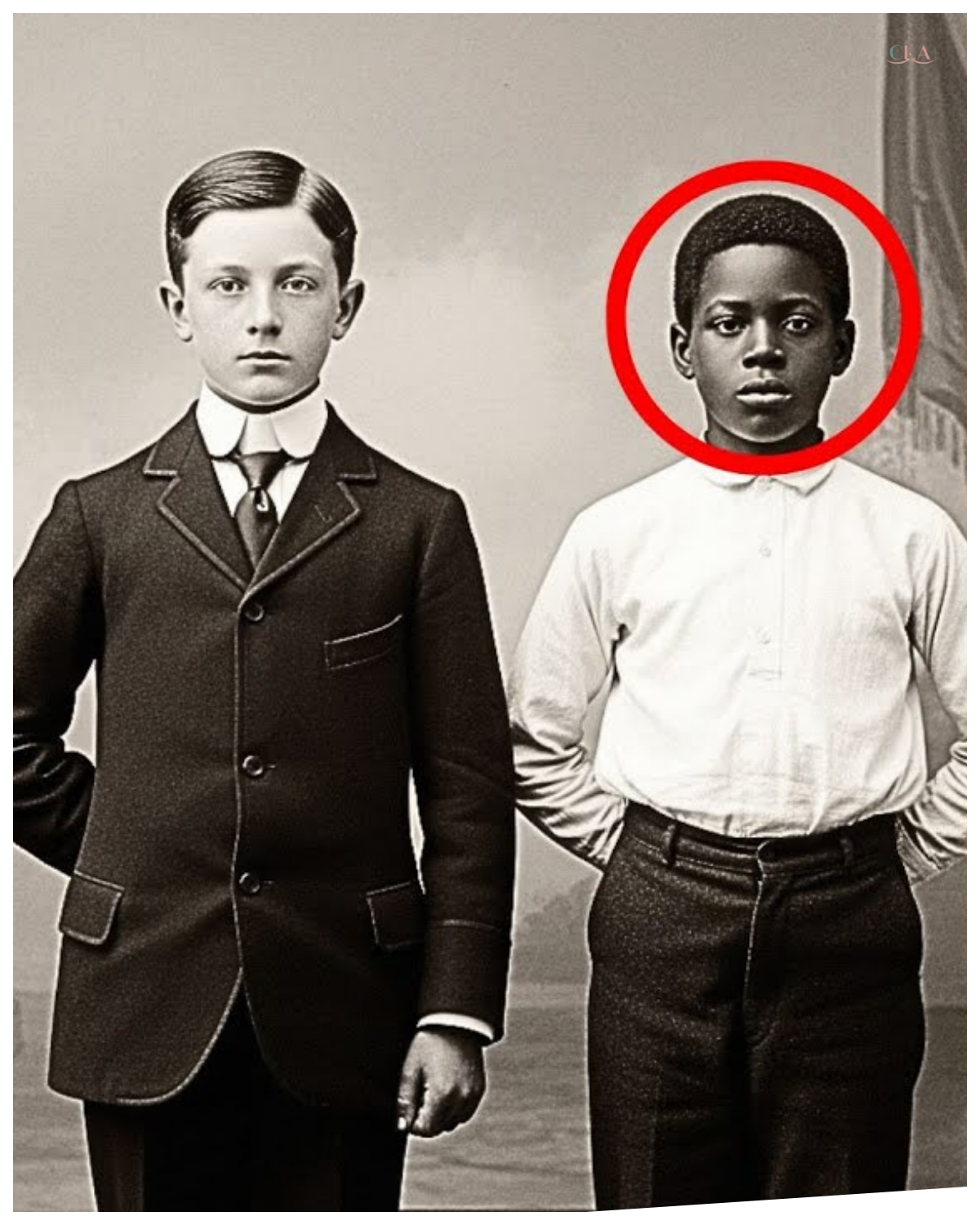

Unlike most photographs in the collection, city buildings, street scenes, official ceremonies, this was a studio portrait of two boys.

The photograph was professionally taken, mounted on thick cardboard backing with the photographers’s name embossed at the bottom.

Jay Patterson, Portrait Studio, Richmond, Val.

The date stamp on the back read October 12th, 1905.

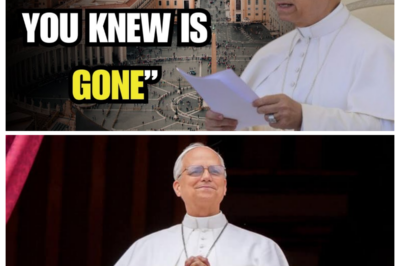

Two boys, both around 10 years old, stood side by side against a painted backdrop of columns and drapes.

The boy on the left was white, dressed in a formal dark suit with a high collar and a silk tie.

His hair was neatly combed, his shoes polished to a shine.

The boy on the right was black, wearing simpler [music] clothes, a clean white shirt and dark trousers, but no jacket or tie.

Despite the difference in attire, both boys stood with identical posture, shoulders back, hands at their sides, looking directly at the camera with serious, almost solemn expressions.

What struck Helen most was their positioning.

[music] They weren’t arranged in the typical manner of the era where black and white subjects would be clearly separated by space or hierarchy.

These boys stood shoulder-to-shoulder, almost touching, as if they were equals, as if they were friends.

Helen turned the photograph over.

On the back, in faded pencil, someone had written two names, Daniel Patterson and Samuel.

Just Samuel, no last name.

Helen felt the familiar tingle of curiosity that came with a mystery.

She carefully set the photograph aside and made a note to research it further.

Something about the image felt significant, though she couldn’t yet articulate why.

As she continued through the box, she kept glancing back at those two young faces, frozen in time, standing together in defiance of everything their society would have expected.

She had no idea that this photograph would lead her into one of the most disturbing stories she would ever uncover.

Helen couldn’t stop thinking about the photograph.

During her lunch break, she scanned the image into her computer and began searching the archives database for any mention of Daniel Patterson or Samuel connected to 1905.

The Patterson name brought up several results.

It was a common surname in Richmond.

But when she filtered by the year 1905 and added photographer, she found what she was looking for.

James Patterson, proprietor of a portrait studio on Broad Street, listed in the city directory from 1903 to 1909.

She expanded her search to newspaper archives, looking for any mention of James Patterson beyond his business advertisements.

What she found made her breath catch.

A brief article from the Richmond Times Dispatch dated October 19th, 1905, just one week after the photograph was taken, carried the headline, “Negro child missing.

Parents seek information.

” Helen read the short paragraph carefully.

Local authorities are investigating the disappearance of a negro boy named Samuel, approximately 10 years of age, last seen in the Jackson Ward neighborhood on the evening of October 16th.

The child’s parents, whose names are being withheld, reported him missing Tuesday morning.

Anyone with information should contact the city police.

The article was buried on page 8, given only three sentences.

Pelen had seen this pattern before in historical newspapers.

Missing black children received minimal coverage, their disappearances treated as routine rather than urgent.

She searched for follow-up articles.

Nothing.

The story simply disappeared from the papers after that single mention.

Helen pulled up census records from 1900 and 1910, searching for any Samuel in the Jackson Ward area, Richmond’s historically black neighborhood.

There were dozens.

Without a last name, finding the right family would be nearly impossible.

She returned to the photograph, studying [music] it with new intensity.

Daniel Patterson stood beside Samuel just days before the boy vanished.

Was it coincidence, or was there a connection? Helen looked up James Patterson in the 1905 city directory again.

The entry listed his studio address and his home address.

She cross- referenced with census records and found James Patterson, age 38, photographer, living with his wife Mary and son Daniel, age 10.

The boy in the photograph was the photographers’s son.

Why would a white photographer take a formal studio portrait of his son standing beside a black child in 1905 Richmond? [music] And why would that black child disappear less than a week later? Helen felt her pulse quicken.

This wasn’t just a forgotten photograph.

This was evidence of something.

Helen spent the next three days diving deeper into James Patterson’s background.

What she discovered complicated her initial assumptions about him.

Patterson wasn’t just a portrait photographer taking pictures of wealthy families and society weddings.

In the newspaper archives, Helen found his name attached to investigative photography, images documenting poor housing conditions, child labor and tobacco factories, and the brutal treatment of black workers in various industries.

In 1903, Patterson had published a series of photographs in a short-lived progressive newspaper called The Richmond Reformer, showing the reality of segregated schools.

The images contrasted well-funded white schools with the crumbling, overcrowded buildings where black children were educated.

The series had caused controversy, and the newspaper had folded within months, likely pressured by advertisers and political interests.

Helen found an editorial Patterson had written, published in The Reformer in May 1904.

A photograph does not lie, though those who view it may choose to look away.

My camera bears witness to truths that polite society would prefer to ignore.

If my work causes discomfort, then it is working as intended.

This was not a man simply operating a commercial portrait studio.

This was someone using photography as a tool for social documentation and reform.

Helen contacted Dr.

Marcus Webb, a historian at Virginia Commonwealth University who specialized in progressive era journalism and racial justice movements.

They met at a coffee shop near the university and Helen showed him copies of what she’d found.

Dr.

Webb examined the photograph of the two boys carefully.

“This is extraordinary,” he said.

“A formal studio portrait of a white child and a black child posed as equals in 1905.

That alone would have been provocative.

” “But given Patterson’s history as a reformist photographer, this feels intentional.

” “What do you think he was documenting?” Helen asked.

Dr.

Webb was quiet for a moment, his finger tracing the edge of the photograph.

“Fear,” he finally said.

I think he was documenting fear.

Look at their faces.

Neither boy is smiling, which was unusual for children’s portraits.

Even then, they look serious, almost worried.

And if Samuel disappeared a week later, Patterson may have suspected something was going to happen.

But what? What could make a child disappear? Dr.

Webb’s expression grew grim.

In 1905, Richmond, many things.

Black children were vulnerable in countless ways.

to violence, to being seized and forced into labor contracts, to being committed to reform schools on fabricated charges.

If Samuel witnessed something, if he became inconvenient to the wrong people, he didn’t need to finish the sentence.

Helen’s next stop was the Richmond Circuit Court Archives, where criminal records from the early 1900s were stored.

She was looking for any cases from October 1905 that might involve a child witness or the Jackson Ward neighborhood.

The clerk, an older man named Gerald, showed her to the records room.

Everything from 1905 should be in this section, he said, gesturing to rows of shelves holding leatherbound volumes and file boxes.

But I should warn you, there was a fire in 1923 that destroyed a significant portion of records from 1900 to 1910.

Helen’s heart sank.

How much was lost? Hard to say, maybe 30%.

And what survived is sometimes water damaged or incomplete.

You’ll have to see what you can find.

For hours, Helen carefully paged through criminal docket books, looking for cases filed in October or November 1905.

Most were routine petty theft, public drunkenness, property disputes.

Then she found something that made her stop.

Case number 1 1905 forcement 2 filed October 18th, 1905.

Commonwealth versus Robert Ashford, James Carile, and Thomas Whitfield.

Assault and battery.

The case file itself was missing, likely destroyed in the fire, but the docket entry included a brief notation.

Witnesses: John Talbot, Samuel, Negro Child, no surname recorded, Emma Watkins.

Case dismissed November 2nd, 1905.

Insufficient evidence.

Samuel, a black child witness in an assault case filed just days after the photograph was taken and 2 days after Samuel was reported missing.

Helen’s hands trembled as she wrote down the information.

She searched for any other mention of the case, but found nothing.

The defendant’s names appeared in property records.

All three were businessmen, property owners, men of standing in the community.

She looked up the dismissal date, November 2nd, 1905.

The case had been dropped exactly 2 weeks after Samuel disappeared.

Helen photographed the docket entry and continued searching.

She found one more reference in a different volume, a petition filed by James Patterson on October 20th, 1905, requesting police protection for a juvenile witness in danger of retaliation.

The petition had been denied with a handwritten notation.

Insufficient grounds.

Petitioners concerns deemed speculative.

The pieces were falling into place.

Samuel had witnessed an assault.

James Patterson, aware of the danger this posed to a black child who could testify against white men, had tried to get him police protection.

When that failed, Patterson had brought Samuel and his own son to his studio and photographed them together, creating a record, evidence that Samuel existed, that he was real, that he mattered.

And then 4 days later, Samuel vanished.

Helen knew she needed to talk to people who understood the history of Jackson Ward, Richmond’s black community in the early 1900s.

She contacted the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia, and was connected with Mrs.

Dorothy Harrison, a 78-year-old historian and descendant of one of Jackson Ward’s founding families.

They met at Mrs.

Harrison’s home, a beautifully maintained Victorian house in the heart of the neighborhood.

Over tea, Helen explained what she’d discovered and showed her the photograph.

Mrs.

Harrison studied it for a long time, her expression unreadable.

My grandmother used to tell stories, she finally said stories about children who disappeared.

Not runaways that happened to, but children who were taken, stolen essentially by a system that didn’t consider black children worthy of protection.

What happened to them? [music] Helen asked.

Different things.

Some were forced into labor contracts, essentially reinsslaved under different names.

Some were committed to industrial schools, which were really prisons.

Some were sent away to other states, to places where cheap child labor was needed, and some, she paused, her voice heavy.

[music] Some simply disappeared, and their families never learned what happened.

Mrs.

Harrison pointed to the photograph.

But families also fought back.

When they could, when they had warning, they ran.

They left everything behind and went north to Philadelphia, New York, Boston, anywhere that might be safer.

They changed their names, created new identities, broke all ties with the South to protect themselves.

You think that’s what happened to Samuel’s family? It’s what I would have done, Mrs.

Harrison said simply.

If my child was in danger, if powerful men wanted him silenced, I wouldn’t wait for the law to protect him.

The law didn’t protect black children.

We protected ourselves.

She stood and retrieved a worn ledger from her bookshelf.

This belonged to my great uncle.

He was a deacon at First African Baptist Church in the early 1900s.

The church kept unofficial records, births, marriages, deaths, but also departures.

When families fled north, the church would note it, partly to remember them and partly to help others who might follow.

Helen watched as Mrs.

Harrison paged through the ledger, her finger tracing down columns of names and dates.

Then she stopped.

“Here,” she said, turning the book toward Helen.

“October 1905.

The Williams family departed suddenly for Philadelphia.

Father Thomas, Mother Ruth, son Samuel, age 10.

May God keep them safe in their journey.

” Helen stared at the entry.

Samuel Williams.

Finally, a full name.

Williams was a common name, Mrs.

Harrison cautioned, and they likely changed it when they reached Philadelphia.

That’s what most families did.

Armed with the name Samuel Williams, and the knowledge that the family had fled to Philadelphia, Helen began the painstaking work of searching northern records.

She reached out to genealological societies, Black History Archives, and church records in Philadelphia.

The challenge was immense.

If the family had changed their name, Samuel Williams could have become anyone.

And with Williams being such a common surname, even finding the right family in 1905, Philadelphia records was like searching for a specific grain of sand on a beach.

Helen created a search profile.

A family of three, Father Thomas, Mother Ruth, son Samuel, arriving in Philadelphia around October or November 1905 from Virginia.

The boy would have been approximately 10 years old.

She found dozens of Williams families in Philadelphia’s black community, but none that perfectly matched.

Then she expanded her search to variant names.

Williamson, [music] Willis, Wilson, any surname that might have been chosen as a close but different alternative.

In the 1910 census for Philadelphia, she found a family that made her pause.

Thomas Wilson, age 39, laborer, born Virginia.

Ruth Wilson, age 35.

Domestic worker, born Virginia.

Samuel Wilson, age 15, born Virginia.

The ages fit.

The Virginia origin fit.

And Wilson was close enough to Williams to be a deliberate choice.

Familiar enough to remember, different enough to hide.

Helen found the family again in the 1920 census.

Thomas was working in a shipyard.

Ruth was a seamstress and Samuel, now 25, was listed as a clerk.

They lived in South Philadelphia in a neighborhood with a growing black middle class.

She traced forward.

In 1930, Samuel Wilson, aged 35, was married to a woman named Clara.

He worked as a postal clerk, a respected position, one of the few federal jobs open to black men at the time.

They had two daughters.

By 1940, Samuel and Clara had moved to a better neighborhood.

His occupation was listed as postal supervisor.

Their daughters were in high school.

Helen felt her pulse quicken.

Samuel had not just survived.

He had thrived.

He had built a life, raised a family, achieved a measure of success despite everything.

She found his death record.

Samuel Wilson died 1975, age 80 in Philadelphia, survived by his wife, Clara, daughters Patricia and Lorraine, and six grandchildren.

But was this the right Samuel? Helen needed more proof.

She reached out to genealological researchers in Philadelphia asking if anyone could help her find living descendants of Samuel Wilson who might have family stories or documents.

Three weeks later, she received an email from a woman named Brenda Collins.

I believe Samuel Wilson was my great-grandfather.

My grandmother is still living.

She would like to speak with you.

Helen flew to Philadelphia on a rainy Tuesday in March.

Brenda Collins met her at the airport and drove her to a nursing home in Mount Ary where Patricia Wilson Collins, aged 94, lived in an assisted living apartment.

Patricia was small and sharpeyed, her mind clear despite her age.

She sat in a comfortable chair by the window, sunlight illuminating the photographs that covered every surface of her small living room.

Children, grandchildren, great grandchildren.

Brenda tells me you’ve been researching my father, Patricia said, her voice strong.

I’m curious what you found.

He never spoke much about his childhood.

Helen showed her the 1905 photograph of the two boys.

Patricia leaned forward, studying it intently.

That’s him, she said quietly.

I don’t know how I know, but I do.

Those eyes.

My father had those same eyes.

Serious, watchful, like he was always expecting something bad to happen.

Did he ever talk about Richmond? About Virginia? Patricia shook her head.

Never.

When we were children, we asked where he grew up, and he would only say down south and change the subject.

My mother told us not to push.

She said some memories were too painful to revisit.

But he kept some things, Brenda interjected.

Grandma, show her the box.

Patricia nodded toward a cabinet.

Brenda retrieved a small wooden box worn smooth with age.

Inside were a few precious items.

A marriage certificate for Thomas and Ruth Wilson from 1892, issued in Virginia.

A baptismal record for Samuel, dated 1895, and a letter yellowed and fragile, dated October 15th, 1905.

Helen’s hands shook as she carefully unfolded the letter.

It was written in careful, formal script, to whom it may concern.

Let it be known that Samuel Williams, age 10, son of Thomas and Ruth Williams, sat for this portrait on October 12th, 1905, in my studio at 412 Broad Street, Richmond, Virginia.

He is a boy of good character and sharp intelligence.

Should any harm come to him or his family, let this photograph serve as testimony that they existed, that they mattered, that they were seen.

James Patterson, photographer.

Helen felt tears prick her eyes.

Patterson had known.

He had documented Samuel, created evidence of his existence because he understood that the boy was in danger.

“There’s something else,” Patricia said.

She reached into the box and pulled out a small photograph separate from the others.

It showed an older white man with graying hair standing in front of a photography studio.

On the back was written, “Mr.

Patterson, the man who saved us.

” “My father kept this his entire life,” Patricia said.

He told me once near the end that a white man had warned his parents, had tried to protect him, had given them money to leave Richmond.

He said that man’s photograph of him with the white boy was meant to say, “This child is worth remembering.

” Back in Richmond, Helen continued investigating the assault case that had triggered Samuel’s disappearance.

With the defendants names, Robert Ashford, James Carile, and Thomas Whitfield, she began researching who these men were and what Samuel might have witnessed.

Property records showed all three men were successful businessmen.

Ashford owned several tobacco warehouses.

Carlilele was a building contractor and Whitfield managed a coal supply company.

They were exactly the kind of men who would have had power and influence in 1905 Richmond.

Helen found their names in society pages, business announcements, even on charitable board memberships.

These were respected citizens, at least in the white community’s eyes.

Then she found a small article in a black newspaper, the Richmond Planet, published on October 21st, 1905.

The planet run by the pioneering black journalist John Mitchell Jr.

are often covered stories that white newspapers ignored.

We have learned that charges of assault against three white businessmen were quietly dismissed this week despite the existence of witnesses to their attack on a negro laborer in Jackson Ward.

Sources indicate that a child witness has disappeared and remaining witnesses have been persuaded to recant their testimony.

Once again, justice proves elusive when the accused are white and the victims are colored.

We ask, “How many more must suffer before the law applies equally to all?” The article didn’t name Samuel, but Helen now understood the full picture.

Three white men had assaulted a black man, possibly severely, possibly fatally.

[music] Samuel had witnessed it.

James Patterson, aware of the case and the danger to Samuel, had documented the boy’s existence through photography.

[music] When Patterson’s petition for protection was denied, Thomas and Ruth Williams made the desperate decision to flee with their son.

Helen found one more piece of the puzzle in the death records.

In late October 1905, a man named Joseph Williams, no relation to Samuel’s family based on her research, died of injuries sustained in an assault.

No one was ever charged.

The three businessmen had gotten away with it.

[music] Samuel’s testimony would have been crucial, but without him, the case collapsed.

The other witnesses, likely intimidated or threatened, recanted.

Justice was denied, but Samuel survived.

His parents quick action, Patterson’s warning, and their own courage saved him.

They lost everything.

Their home, their community, their history.

But they kept their son alive.

Helen sat in the archives surrounded by documents that told a story of injustice and resilience, of a system designed to silence black voices and the people who fought back in whatever ways they could.

She thought about Samuel living his entire adult life as Samuel Wilson, carrying the weight of what he’d witnessed, never speaking of it even to his own children.

She thought about Thomas and Ruth, who had made the hardest choice parents could make to uproot everything for their child’s safety.

and she thought about James Patterson, who had used his privilege and his craft to bear witness, to create evidence to say, “This child matters.

” Helen knew the story wasn’t complete without finding Daniel Patterson’s descendants.

The boy in the photograph, standing beside Samuel, was now part of this history, too.

She began searching for Daniel Patterson in records after 1905.

She found him in the 1910 census, age 15, still living with James and Mary Patterson in Richmond.

By 1920, Daniel had moved to Washington DC, where he worked as a newspaper photographer following his father’s profession.

The trail led Helen to Daniel’s grandson, a retired journalist named Michael Patterson, who lived in Arlington, Virginia.

When Helen called him and explained her research, he was immediately interested.

My grandfather never talked much about his childhood either, Michael said when they met at his home the following week.

But I found some of his papers after he died.

There was a journal from when he was young.

Let me find it.

Michael returned with a leatherbound notebook, weathered but intact.

He opened it to a page marked with a ribbon.

This entry is from October 1905.

My grandfather was 10 years old.

He wrote, “Today, father brought a boy named Samuel to the studio.

He told me Samuel was in danger and that we needed to remember him to make sure people knew he was real.

We stood together for the photograph.

Samuel was scared but trying to be brave.

” Father said, “Sometimes taking a picture is the most important thing a person can do.

” 3 days later, Samuel was gone.

Father tried to find out what happened to him, but no one would say.

I think about him often and hope he’s safe somewhere.

Michael looked up at Helen.

My grandfather carried guilt about this his entire life.

He felt he should have done more, though he was just a child.

When he became a photographer himself, he specialized in documenting civil rights protests in the [music] 1960s.

He said he was finishing his father’s work, making sure people who were fighting for justice were seen and remembered.

Helen showed Michael the photograph of Samuel Wilson as an older man surrounded by his family.

He survived, she said.

He built a good life.

Your great-grandfather’s photograph may have helped save him.

It was evidence that Samuel existed, that he mattered enough to be documented.

Michael stared at the image for a long moment.

My grandfather would have wanted to know this.

He died thinking Samuel had been killed.

“Would you like to meet Samuel’s granddaughter?” Helen asked.

She’s here in Richmond visiting.

[music] I thought you both should know the full story.

Michael nodded, emotion evident in his face.

“Yes, I’d like that very much.

” That afternoon, Helen brought Michael Patterson and Brenda Collins together at the municipal archives.

She laid out the full story, the photograph, the assault case, the disappearance, the flight north, Samuel’s life in Philadelphia, and Daniel’s lifetime of carrying the weight of that childhood memory.

They sat on opposite sides of the table, two families connected by a single photograph taken 119 years ago.

Brenda studied the image of the two boys.

My great-grandfather kept this story locked inside him for 70 years.

He never went back to Richmond.

He never used his birth name again, but he kept Mr.

Patterson’s letter and photograph until the day he died.

Three months later, the Richmond Municipal Archives opened a new exhibition titled Bearing Witness: Photography and Justice in 1905 Richmond.

The centerpiece was the photograph of Samuel Williams and Daniel Patterson, enlarged and displayed alongside the full story Helen had uncovered.

The exhibition room was packed for the opening.

Helen stood to the side, watching as people filed past the displays.

the photograph, James Patterson’s letter, excerpts from Daniel’s childhood journal, census records showing Samuel Wilson’s life in Philadelphia, newspaper articles about the assault case and its dismissal.

Patricia Wilson Collins had traveled from Philadelphia for the opening, accompanied by Brenda and other family members.

Michael Patterson stood with them and Helen watched as these two families, separated by race, connected by history, shared stories and photographs.

Helen stepped to the podium to address the crowd.

This photograph was taken on October 12th, 1905.

She began, “In it, you see two 10-year-old boys standing side by side in a Richmond photography studio.

One is white, one is black.

In the segregated South of 1905, this alone would have been unusual.

But this photograph is more than unusual.

It’s an act of documentation, of defiance, and of hope.

” She told the story methodically, walking the audience through each discovery.

She explained how Samuel Williams witnessed a crime, how James Patterson tried to protect him, how the family fled to survive, and how Samuel lived a long life under a new name, never returning to the place of his birth.

James Patterson understood something crucial, Helen continued.

He understood that photographs could serve as evidence not just of events, but of existence itself.

In a society that systematically rendered black lives invisible, that dismissed black testimony, that allowed black children to disappear without investigation, Patterson used his camera to say, “This child is real.

He exists.

[music] He matters.

Remember him.

” She gestured to the enlarged photograph.

“Samuel Williams became Samuel Wilson and lived until 1975.

He raised [music] daughters, worked as a postal supervisor, served his community.

He never spoke of Richmond, never [music] acknowledged his past because the trauma of that October was too deep.

But he kept three things.

His parents’ marriage certificate, his baptismal record showing his birth name, and James Patterson’s letter explaining why this photograph was taken.

Helen turned to where Patricia and Michael stood together.

Today, Samuel’s granddaughter and James Patterson’s great-grandson meet for the first time.

[music] Two families connected by an act of courage and compassion across racial lines in one of the darkest periods of American history.

Patricia stepped forward, her voice clear and strong despite her age.

My father taught us to be proud, to work hard, to never accept injustice.

But he never told us why.

He never explained where those lessons came from.

Now I understand.

He learned them from parents who risked everything to save him, and from a white man who saw him as human when society said he was not.

Michael spoke next.

My grandfather lived with guilt because he couldn’t save Samuel.

But the photograph they took together did save him.

It proved he existed, created a record, gave his family evidence to carry forward.

Both our grandfathers understood that documentation matters, that bearing witness is an act of resistance.

The exhibition included a section on the broader context, the system of legal and extralegal violence that made black children vulnerable, the networks of resistance that helped families escape, and the role of progressive journalists and photographers in documenting injustice.

Dr.

Webb, the historian who had helped Helen with her research, gave a talk about the period.

What this photograph shows us, he said, is that even in the most oppressive systems, there were people who resisted.

James Patterson risked his reputation and his business to document Samuel.

Thomas and Ruth Williams made the agonizing choice to abandon everything they knew to protect their son.

These acts of courage were happening constantly, but they were rarely documented.

Most were lost to history.

This photograph survived by accident, forgotten in a box in a basement.

How many other stories are still waiting to be discovered? As the evening wound down, Helen stood before the photograph one last time.

She thought about all the images she’d handled in her career as an archavist.

Thousands of faces looking out from the past, most of them anonymous, their stories lost.

But sometimes, with patience and attention, those stories could be recovered.

Sometimes in the margins, in the corners, in the overlooked boxes and forgotten files, the truth waited to be found.

The photograph of Samuel Williams and Daniel Patterson would travel to museums, would be studied by historians, would appear in textbooks about [music] the progressive era and the long struggle for civil rights.

But its greatest achievement had already occurred in the moment James Patterson released the shutter, creating evidence that a black child in danger existed and mattered.

And in the reunion of two families who learned that courage and compassion had connected them across a century of silence.

Helen looked at the two boys in the photograph, 10 years old, serious and solemn, standing together against a backdrop of painted columns.

One had lived his life under his true name, carrying forward his father’s work of documenting injustice.

The other had lived under a new name, building a family and a legacy in a place far from his birthplace.

Both had been shaped by that October day in 1905.

Both were testaments to survival and resistance.

and both finally were remembered not as victims or symbols, but as real children who became [music] real men whose lives mattered, whose stories deserve to be told.

As people filed out of the exhibition, Helen heard fragments of conversation, questions about their own family histories, discussions about what other stories might be hidden in photographs and archives, commitments to search, to ask, to remember.

That was what history should do, Helen thought.

not just preserve the past, but illuminate it, connect it to the present, [music] and remind us that every person who came before us was as real and complex as we are now.

Every photograph holds a story.

Every archive contains truth waiting to be uncovered.

Every forgotten name deserves to be remembered.

The photograph of two boys taken in fear and hope 119 years ago had finally told its full story.

And in doing so, it had connected past and present, injustice and resistance, silence and witness, eraser and memory.

News

Pope Leo XIV SILENCES Cardinal Burke After He REVEALED This About FATIMA—Vatican in CHAOS!

A Showdown in the Vatican: Cardinal Burke Confronts Pope Leo XIV Over Fatima Revelations In a dramatic turn of events…

ARROGANT REPORTER TRIES TO HUMILIATE BISHOP BARRON ON LIVE TV — HIS RESPONSE LEAVES EVERYONE STUNNED When a Smug Question Turns Into a Public Trap, How Did One Calm Answer Flip the Entire Studio Against Its Own Host? A Live Broadcast, a Loaded Accusation, and a Moment of Brilliant Composure Now Has Millions Replaying the Exchange — Click the Article Link in the Comment to Watch the Scene Everyone Is Talking About.

Bishop Barron Confronts Hostile Journalist in a Live TV Showdown In a gripping encounter that captivated audiences, Bishop Robert Barron…

Angry Protesters Disrupt Bishop Barron’s Mass… His Response Moves Everyone to Tears

A Transformative Encounter: Bishop Barron’s Unforgettable Sunday Mass What began as an ordinary Sunday Mass at the cathedral took an…

Bishop Barron demands Pope Leo XIV’s resignation in fiery speech — world leaders respond

A Historic Confrontation: Bishop Barron Calls for Pope Leo XIV’s Resignation In an unprecedented turn of events, the Vatican finds…

Pope Francis leaves a letter to Pope Leo XIV before dying… and what’s written in it makes him cry.

The Emotional Legacy of Pope Francis: A Letter to Pope Leo XIV In a poignant moment of transition within the…

POPE LEO XIV BANS THESE 12 TEACHINGS — THE CHURCH WILL NEVER BE THE SAME AFTER THIS When Ancient Doctrine Is Suddenly Silenced, What Hidden Battle Is Tearing Through the Heart of the Vatican — and Why Are Believers Around the World Being Kept in the Dark? Secret decrees, quiet councils, and forbidden teachings now threaten to rewrite centuries of faith — Click the Article Link in the Comment to Discover What the Church Isn’t Saying.

Pope Leo XIV Challenges Tradition with Bold Ban on Twelve Teachings The Catholic Church stands on the brink of transformation…

End of content

No more pages to load