This 1904 wedding portrait looks elegant until you see what the groom is hiding.

The afternoon sun filtered through the windows of Patterson’s antique shop in downtown Philadelphia, illuminating dust moes that danced above tables crowded with forgotten treasures.

Margaret Sullivan moved carefully between displays of tarnished silver, faded quilts and stacks of old photographs.

At 58, she’d spent three decades restoring historical photographs, bringing clarity to faded memories and preserving fragments of lives long past.

She paused at a wooden crate marked estate sale mixed items.

Inside lay bundles of letters, postcards, and several framed photographs wrapped in yellowed newspaper.

Margaret unwrapped them one by one until her hands touched a larger frame approximately 11 by 14 in.

Its glass cracked at one corner.

She carefully removed the frame and held the photograph toward the window light.

Her breath caught.

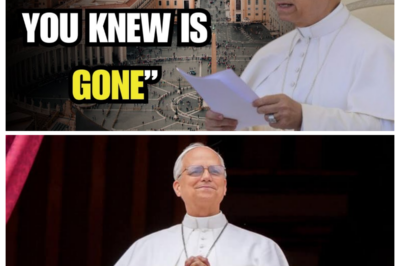

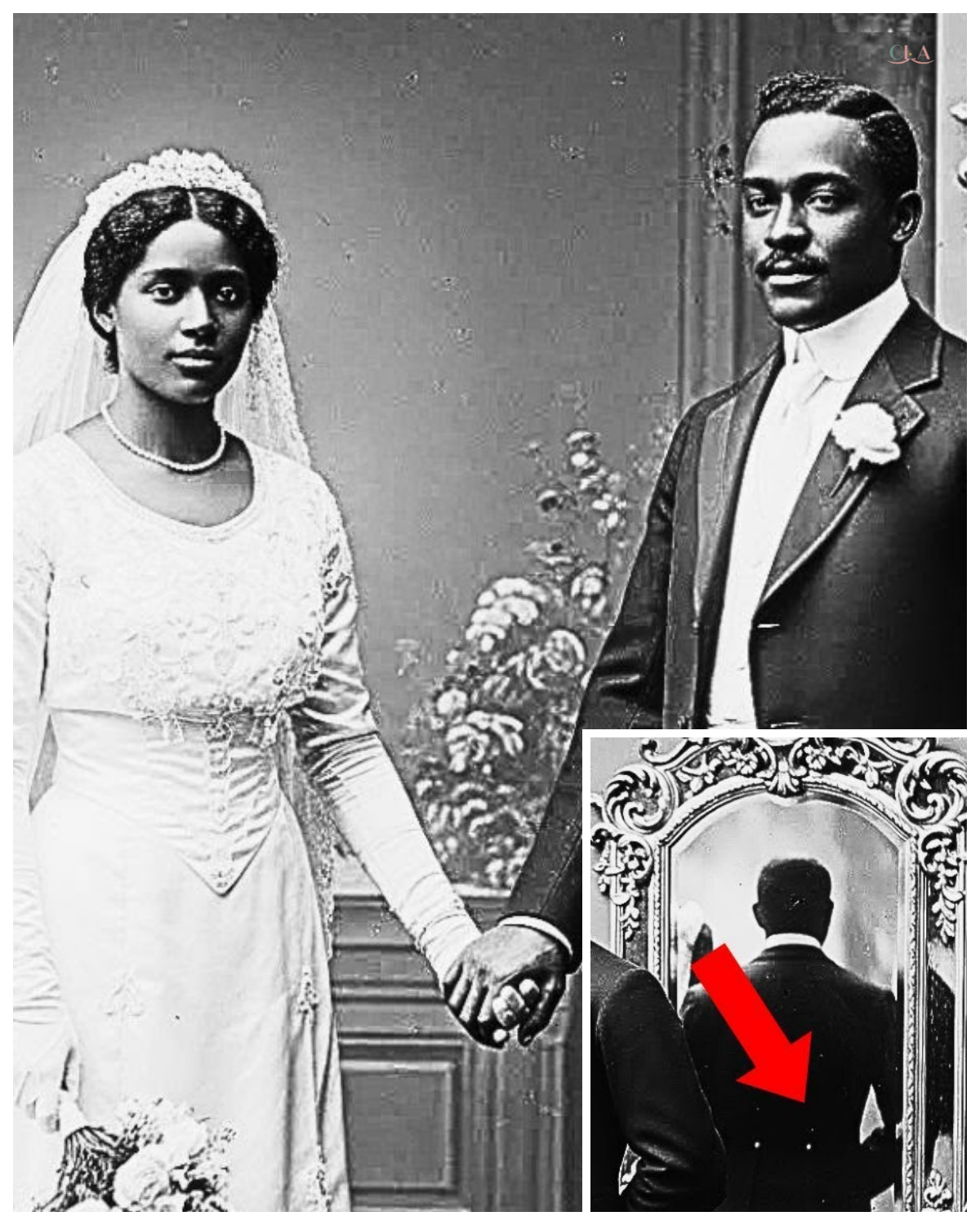

The image showed an elegant black couple in wedding attire standing in what appeared to be a professional photography studio.

The bride wore an exquisite white silk dress with intricate pearl beading along the bodice and sleeves, her hair styled in the elaborate fashion of the early 1900s.

A delicate veil cascaded from a floral crown, and she held a bouquet of roses.

The groom stood beside her in an immaculate black tail coat, striped trousers, and white bow tie, his posture dignified and proud.

Behind them hung elegant drapes, and to their right stood an ornate gilded mirror, its baroque frame catching the studio lights.

The couple’s hands were clasped together at the front, their faces turned toward the camera with expressions of quiet joy and determination.

Margaret studied the photograph with her trained eye.

The quality was exceptional for 1904.

Sharp focus, professional lighting, careful composition.

Whoever had photographed this couple understood their craft and had treated their subjects with respect and artistry.

For a black couple to afford such elaborate wedding attire and professional photography in that era spoke of success, education, and courage.

Yet something about the image unsettled her.

Perhaps it was the tension she detected in their shoulders, or the way their smile seemed to hold more than simple wedding joy.

There was defiance in their eyes, determination in their stance.

She turned the photograph over on the backing board written in careful script.

Jonathan and Clara, August 15th, 1904, Philadelphia.

Below that, in different handwriting, they survived.

Margaret felt a chill run through her.

What did they survive? She looked at the photograph again, sensing there was more to this image than a simple wedding portrait.

Something hidden, something the camera had captured that required closer examination.

“How much for this?” she asked the shop owner, already knowing she had to have it.

Margaret’s restoration studio occupied the second floor of a narrow brick building in the historic district, its north facing windows providing perfect natural light.

She carried the photograph directly to her examination table, carefully removing it from the damaged frame and assessing its condition.

The print itself was remarkably well preserved despite the cracked glass.

The original photographer had used high-quality materials.

Margaret set up her professional lighting system, positioning adjustable lamps at precise angles to eliminate glare and reveal every detail the photograph held.

She began with a standard visual examination, using her magnifying loop to study the couple’s faces, their clothing, the studio backdrop.

Jonathan appeared to be in his early 30s, his features strong and intelligent, his grooming impeccable.

Clara looked slightly younger, perhaps late 20s.

Her beauty enhanced by confidence and dignity.

Their wedding clothes were expensive, tailored, suggesting they belong to Philadelphia’s black professional class.

Margaret moved her examination to the background elements, the draped fabric, the studio furniture, the lighting equipment barely visible at the frames edge.

Then her loop passed over the ornate mirror positioned behind and to the right of the couple.

She stopped, moved back, adjusted her lighting.

In the mirror’s reflection, she could see what the straight-on camera angle had hidden.

Jonathan’s right arm, positioned behind his back, his hand gripping something dark and metallic.

Margaret increased the magnification, her heart beginning to race.

It was a revolver, clearly visible in the mirror’s reflection, held firmly in Jonathan’s right hand, concealed from the front view, but captured perfectly in the angled glass.

Margaret sat back, her mind racing.

Why would a groom hold a gun during his wedding photograph? She looked closer at the mirror’s reflection, examining other details she’d initially missed.

There, in the background of the reflection, barely visible through what appeared to be a studio window, shadows, human shapes, multiple figures standing outside.

She adjusted her lighting again, this time using oblique illumination to enhance contrast.

The shapes became clearer.

Men, at least five or six, visible through the window in the mirror’s reflection.

One appeared to be holding something long, a torch.

Another’s posture suggested aggression, menace.

Margaret’s hands trembled slightly as she reached for her camera to document what she was seeing.

This wasn’t just a wedding portrait.

This was a photograph taken under threat.

A couple posing for their wedding picture while danger literally waited outside while the groom held a weapon behind his back, prepared to defend his bride and himself.

She photographed every detail, then returned to the inscription on the back.

They survived.

The words took on new urgent meaning.

Survived what? The wedding day itself? An attack? She looked at the date again, August 15th, 1904.

Margaret crossed to her reference library and pulled down a volume on Philadelphia history.

She needed to know what had happened in this city on that specific date.

What could have made a wedding so dangerous that a groom felt compelled to arm himself even while posing for a portrait? The Philadelphia Public Libraryies history section smelled of old paper and preservative chemicals.

Margaret sat at a scarred wooden table surrounded by bound newspaper volumes from 1904.

Her notebook filling with increasingly disturbing information.

August 1904 had been a violent month in Philadelphia.

The city’s black community, which had grown substantially since the Civil War, faced increasing hostility from white residents who resented their economic success and political activism.

The newspapers, even accounting for the racist language common to the era, documented a pattern of intimidation, property destruction, and physical attacks.

Margaret found references to several incidents in mid- August.

A blackowned pharmacy vandalized.

A church meeting disrupted by a mob.

A lawyer’s office burned.

The black newspapers of the period which she found in a separate archive told fuller stories that the white press had minimized or ignored entirely.

Then she found it.

A small article in the Philadelphia Tribune, a black newspaper dated August 18th, 1904.

The wedding of Mr.

Jonathan Williams.

Corners and Miss Clara Thompson on August 15th proceeded despite threats from local agitators.

The ceremony held at Bethl AM Church was attended by over 100 members of our community who stood guard throughout.

The couple’s courage and refusing to postpone their union in the face of intimidation has inspired many.

Both Mr.

Williams and Miss Thompson are well-known advocates for our people’s rights and advancement.

Margaret’s heart raced.

She’d found them.

Jonathan Williams and Clara Thompson.

Now she had names to trace.

She spent the next two hours searching for more information about the couple.

Jonathan Williams appeared frequently in legal notices.

He’d been an attorney who took cases challenging segregation and public accommodations, employment discrimination, and voting rights restrictions.

He’d graduated from Howard University Law School in 1898, one of the few black lawyers practicing in Philadelphia.

Clara Thompson had been a teacher at the Institute for Colored Youth, one of the oldest schools for black students in the country.

Several articles mentioned her work organizing literacy programs and advocating for equal funding for black schools.

They were activists, fighters for justice.

Exactly the kind of people who would have attracted a violent opposition from white supremacists.

Their wedding wasn’t just a personal celebration.

It was a political statement, a refusal to be intimidated into hiding or postponing their lives.

Margaret found one more crucial piece of information in a society column from September 1904.

Mr.

and Mrs.

Jonathan Williams have departed Philadelphia for an extended journey.

Friends wished them safety and success in their endeavors.

The phrasing was careful, almost coded.

They’d left the city.

Whether temporarily or permanently, the record didn’t say, but the photograph’s inscription said they survived.

Margaret needed to know what happened during that wedding.

Why Jonathan had held a gun behind his back and what became of this remarkable couple afterward.

She gathered her notes and headed back to her studio, determined to find the rest of their story.

Back in her studio, Margaret examined the photograph again with fresh understanding.

Knowing who Jonathan and Clara were, knowing the danger they’d faced, every detail now carried weight.

She studied the mirror’s reflection more carefully, trying to identify the threatening figures visible through the window.

Then she noticed something she’d missed before.

In the lower right corner of the photograph, barely visible against the dark background, was a small embossed mark.

She positioned her strongest magnifying glass over it and adjusted her lighting.

Samuel Chen Photography Studio, 412 South Street, Philadelphia.

Margaret’s eyebrows rose.

Chen, an Asian photographer in 1904 Philadelphia.

That was unusual enough to be traceable.

She made a note to research the studio’s history, but first she wanted to examine every detail the photograph held.

She created a series of highresolution photographs of different sections, particularly the mirror’s reflection.

Using careful lighting and her professional camera, she documented the gun in Jonathan’s hand, the threatening figures outside the window, and every visible detail of the couple’s expressions.

Under extreme magnification, she could see the tension in Jonathan’s jaw, the way his left hand gripped Clara’s with protective intensity.

Clara’s smile, which appeared serene at normal viewing distance, showed signs of strain around her eyes.

She knew what waited outside, knew her husband held a weapon behind his back, yet she stood tall and dignified for this portrait.

Margaret’s phone rang, interrupting her examination.

It was her colleague, Robert Hayes, a historian who specialized in Philadelphia’s black community history.

Robert, I need your help, Margaret said after brief greetings.

I found a photograph from 1904.

A black couple, Jonathan Williams and Clara Thompson, their wedding day.

Have you heard those names? There was a sharp intake of breath.

Jonathan Williams, the lawyer.

Margaret, where did you find this photograph? An antique shop.

You know them? Know of them? Robert said, excitement clear in his voice.

Jonathan Williams is something of a legend in Philadelphia black history, but documentation about him is scarce.

He and his wife disappeared from the city in late 1904.

Some historians think they were killed.

Others believe they relocated to avoid violence.

Where they went, what happened to them, it’s been a mystery for decades.

Margaret felt her pulse quicken.

Robert, this photograph was taken on their wedding day, August 15th, 1904.

And there’s something you need to see.

Can you come to my studio? I’m 20 minutes away.

While waiting, Margaret researched Samuel Chen.

She found references to his photography studio and city directories from 1902 through 1906, located in a mixed neighborhood where black, Asian, and immigrant communities overlapped.

One article from 1903 mentioned Chen’s studio as providing dignified portraiture to all citizens regardless of race.

That single phrase told Margaret volumes, “In an era of rigid segregation, Chen had explicitly served clients others refused.

” His studio would have been one of the few places where a black couple like Jonathan and Clara could get professional wedding photographs taken with respect and artistry.

Robert arrived exactly 20 minutes later, slightly breathless from climbing the stairs.

Margaret had the photograph laid out under her best lighting with her documentation photographs arranged beside it.

“Look at the mirror,” she said simply.

Robert bent over the image, his eyes widening as he saw the reflection, the gun, the threatening figures.

He straightened slowly, his face pale.

“My god!” They took their wedding portrait while under actual threat.

That’s not just courage, Margaret.

That’s defiance.

Robert spent an hour examining every detail of the photograph, taking notes, and occasionally shaking his head in amazement.

When he finally sat back, his expression was thoughtful.

Samuel Chen, he said, I need to find out more about him.

A photographer who would document this, who would position a mirror to capture what was really happening.

That’s someone who understood he was creating historical evidence, not just a wedding portrait.

Do you think Chen positioned that mirror deliberately? Margaret asked.

Look at the composition, Robert pointed.

Everything else in this photograph is perfectly balanced, professionally arranged.

That mirror’s placement seems almost awkward from a purely aesthetic standpoint until you realize it captures exactly what needs to be seen.

Chen knew what he was doing.

They decided to split their research.

Robert would investigate the Chen photography studio and its proprietor, while Margaret would try to trace what happened to Jonathan and Clara after they left Philadelphia.

Before Robert left, he mentioned one more thing.

There’s a woman you should talk to, Dr.

Patricia Freeman at Temple University.

She’s writing a book about black resistance during the progressive era.

If anyone knows more about Jonathan Williams and his activism, it’s her.

Margaret called Dr.

Freeman that evening.

The historian’s voice was warm but cautious when Margaret explained her discovery.

I’ve searched for years for photographs of Jonathan Williams, Dr.

Freeman said.

All I found are newspaper illustrations which are often inaccurate or deliberately unflattering.

You’re telling me you have an actual photograph from his wedding day? Not just a photograph, Margaret said.

Evidence? Can I show you? They arranged to meet the next morning at Margaret’s studio.

Margaret spent the evening creating detailed prints of the photograph and her enhanced images of the mirror’s reflection.

She wanted Dr.

Freeman to see everything clearly.

Sleep came fitfully.

Margaret kept thinking about Jonathan and Clara, standing in that studio, knowing danger waited outside, choosing to create this record of their love and commitment anyway.

What kind of strength did that require? What happened after the photographers’s flash faded and they had to leave the studio’s safety? Dr.

Freeman arrived promptly at 9, a tall woman in her 60s with intelligent eyes and an air of focused intensity.

She set her briefcase down and approached the photograph Margaret had laid out.

For a long moment, she simply stared.

Then she pulled out a magnifying glass from her briefcase and bent over the image, examining every detail.

When she finally looked up, her eyes were wet.

“Do you understand what you found?” she asked quietly.

This isn’t just a photograph.

This is proof.

Proof that they existed.

Proof of their dignity.

Proof of their resistance.

Jonathan Williams has been dismissed by some historians as possibly mythological.

His achievements exaggerated by oral tradition.

But here he is, real and documented, standing with his bride on the day they defied a mob.

“Tell me about him,” Margaret said.

“Tell me who they were.

” Dr.

Freeman pulled out her notes and began to share what years of research had uncovered.

Dr.

Freeman’s research painted a portrait of two remarkable people.

Jonathan Williams had been born in 1872 in Virginia, the son of formerly enslaved parents who’d built a small but successful grocery business during reconstruction.

He’d excelled in school, won a scholarship to Howard University, and graduated from their law school at the top of his class in 1898.

He’d moved to Philadelphia specifically because its black community was large, organized, and politically active.

The city had a substantial black middle class, doctors, lawyers, teachers, business owners who fought against increasing segregation and discrimination.

Jonathan had joined their ranks, taking cases that challenged Jim Crow practices creeping into northern cities.

He won several important cases, Dr.

Freeman explained, showing Margaret photocopied court documents.

In 1902, he successfully sued a restaurant that refused to serve black customers.

In 1903, he represented a black teacher fired for teaching about reconstruction accurately.

These victories made him both celebrated in the black community and hated by white supremacists.

Clare Thompson’s background was equally impressive.

Born in 1876 in Philadelphia to a family of free black professionals, she’d attended the Institute for Colored Youth, and stayed on as a teacher after graduation.

She’d organized literacy programs for adult students, fought for equal resources for black schools, and written articles for black newspapers about education and women’s rights.

They met at a meeting of the Philadelphia NOAACP precursor organization in 1903.

Dr.

Dr.

Freeman continued, “By all accounts, they were a dynamic couple, both brilliant, both committed at justice, both unafraid to challenge the status quo.

Their engagement was announced in early 1904, and that’s when the threats began.

” “What kind of threats?” Margaret asked.

“Letters, mostly warnings that upy black people who didn’t know their place would face consequences.

Anonymous messages saying their wedding would be disrupted.

Jonathan’s office received threatening visits.

Clara’s school was vandalized twice, but they refused to postpone or cancel their wedding.

In fact, they made it more public, more visible.

They invited the entire black community to witness their union.

Doctor Freeman pulled out a newspaper clipping.

This is from the Philadelphia Tribune, August 14th, 1904, the day before the wedding.

It’s an editorial praising Jonathan and Clara’s courage and calling on the community to support them.

It mentions that security precautions were being taken, that the church would be guarded, that people should come armed if necessary.

Margaret felt a chill.

The community expected violence.

They were prepared for it.

Dr.

Freeman corrected.

There’s a difference.

This wasn’t fear.

It was readiness.

The black community in Philadelphia in 1904 understood that respectability and education didn’t protect them from white violence.

So, they organized, they prepared, and they defended themselves when necessary.

She pointed to the photograph.

That gun Jonathan’s holding, that wasn’t paranoia.

That was survival.

and Clara standing there with him, knowing he had that weapon, knowing what might happen.

That was courage of the highest order.

The inscription says they survived, Margaret said.

What happened after the wedding? Dr.

Freeman’s expression grew troubled.

That’s where the record gets murky.

They left Philadelphia shortly after the wedding, and there are conflicting accounts of where they went and why.

Dr.

Freeman spread several documents across Margaret’s work table, city directories, census records, newspaper clippings, creating a timeline of what happened after the wedding.

They left Philadelphia in September 1904, she explained.

The last reference I found is a farewell notice in the Tribune thanking the community for their support and saying they were pursuing opportunities elsewhere.

That kind of vague language usually meant they were leaving for safety reasons.

Where did they go? Margaret asked.

That’s the mystery.

Some oral histories claim they went to Chicago, others say New York or even Canada.

I found a possible reference to a Jonathan Williams practicing law in Chicago in 1906, but I couldn’t confirm it was the same man.

There were several Jonathan Williams’.

It was a common name.

Margaret studied the timeline, thinking about the photograph and its inscription.

They survived.

And someone had known what happened to them, known they’d made it through whatever danger they faced.

“What about Samuel Chen?” Margaret asked.

“Have you heard anything from Robert about the photographer?” As if summoned by the question, her phone rang.

It was Robert, his voice excited.

“Margaret, I found Chen’s daughter.

She’s 93 years old, living in a nursing home in Chinatown.

Her name is Lily Chen, and she remembers her father’s photography studio.

She’s willing to talk to us.

Margaret felt her pulse quicken.

When? This afternoon, if you’re available.

She’s sharp as attack, her nurse said.

But her memories from childhood are clearer than recent events.

We should visit soon.

Margaret looked at Dr.

Freeman, who was already gathering her things.

We’re coming, Margaret said.

The Chinatown nursing home occupied a converted rowhouse on a narrow street filled with restaurants and shops.

The nurse who met them explained that Lily Chen was indeed remarkably lucid for her age, though she tired easily.

They found her in a sunny common room, a tiny woman with white hair and bright, intelligent eyes.

When Margaret explained why they’d come and showed her the photograph, Lily’s face lit up with recognition.

“I remember this,” she said, her voice surprisingly strong.

“I was just 8 years old, but I remember.

Father let me watch from behind the curtain while he worked.

This was the wedding photograph that changed everything.

Margaret exchanged glances with Robert and Dr.

Freeman.

I changed everything.

How? Lily touched the photograph gently.

The couple came to our studio very early that morning.

Father usually didn’t work on Sundays, but they’d paid extra because they needed the photographs quickly.

They said their wedding was that afternoon, and they wanted the portraits before the ceremony.

Before? Margaret asked, surprised.

They told father there might be trouble, that they wanted to make sure they had proper wedding photographs even if something went wrong.

Father understood he’d faced discrimination himself, knew what it meant to live with threats.

So he agreed.

Lily pointed to the mirror in the photograph.

Father positioned that mirror deliberately.

I heard him explain it to the groom.

He said, “I will photograph what you show the world, but I will also document the truth.

” The groom understood.

He said, “Good.

People should know we stood strong even when we had to stand armed.

” Margaret leaned forward.

What happened after he took the photograph? Lily’s expression grew serious.

They left to get married.

But that evening, very late, they came back.

Lily Chen’s hands trembled slightly as she continued her story, her voice dropping as if the events of that night 54 years ago, still required discretion.

It was past midnight when someone knocked on our door.

Father was still awake, developing the wedding photographs.

He’d promised to have them ready quickly.

When he opened the door, the couple stood there, the bride still in her wedding dress, the groom still in his formal clothes, but both looking exhausted and frightened.

Behind them were maybe a dozen other people, some carrying bags and bundles.

Father let them all in immediately and locked the door.

I watched from the stairs.

I should have been asleep, but I’d heard the commotion.

Mother brought them water and food while Father finished developing the photographs.

What happened? Dr.

Freeman asked gently.

The wedding had gone forward at the church with guards posted all around.

But afterward, when they left for the reception, a mob was waiting.

Not just a few men, dozens, maybe over a hundred.

The community had expected trouble and came armed, and there was a standoff.

No shots were fired, but it was close.

The police eventually dispersed the crowd, but it was clear Jonathan and Clara couldn’t stay in Philadelphia.

Lily paused, gathering her memories.

A father’s studio had a basement connected to the old underground railroad tunnels.

Many buildings in that neighborhood did.

People had hidden escaped slaves there before the Civil War.

Father told them they could hide there until arrangements were made to get them out of the city safely.

Margaret felt chills run down her spine.

The Underground Railroad tunnels used to save people fleeing slavery were being used again 40 years later to protect black people from white violence.

They stayed in our basement for 3 days, Lily continued.

Father brought them food and newspapers.

Other people from their community came through the tunnels at night to visit, bringing money, documents, addresses of safe places in other cities.

I remember the bride thanking my father for the photographs, saying they were proof that their love was stronger than hate.

Where did they go? Robert asked.

Father arranged for them to travel with a Chinese merchant who was going to Chicago.

This was before the immigration act restrictions tightened even more against Chinese people, and father knew merchants who moved between cities.

Jonathan and Clara left Philadelphia hidden in a cargo wagon dressed in workers’s clothes.

Father said they were going to start over somewhere they could continue their work, but with less immediate danger.

Lily reached into her pocket and pulled out a small worn leather notebook.

Father kept notes on his most important clients.

He said some photographs were historical documents, not just portraits.

I saved this after he died in 1952.

She opened the notebook to a page marked with ribbon.

There, in careful handwriting was an entry.

Jonathan Williams and Clara Thompson.

Wedding portrait, August 15th, 1904.

Subjects faced mob violence, but stood with dignity.

Photograph documents, both their love and their resistance.

They departed Philadelphia August 18th for Chicago, Illinois, accompanied by letters of introduction to Chicago.

NAACP contacts.

May they find safety and continue their important work.

Prints delivered before departure.

Additional prints retained for historical record.

Below that was an address.

CEO Robert Abbott, Chicago Defender newspaper.

Margaret’s hands shook as she photographed the notebook page.

Robert Abbott had founded the Chicago Defender, one of the most influential black newspapers in American history.

If Jonathan and Clara had gone to Chicago with an introduction to Abbott, there might be records, articles, documentation.

Did your father ever hear from them again? Dr.

Freeman asked.

Lily smiled.

One letter about 6 months later.

I don’t have it anymore.

It was lost in a fire years ago, but I remember father reading it aloud to mother.

They said they were safe, working, and grateful.

They signed it, the couple who survived.

That’s why father wrote that inscription on the back of the photograph to remind himself that courage could triumph over hate.

Armed with Robert Abbott’s name and the Chicago Defender Connection, Margaret, Robert, and Dr.

Freeman launched into research with renewed energy.

Doctor Freeman had colleagues at the University of Chicago who could access the defender archives while Robert contacted historical societies on Chicago’s South Side where Jonathan and Clara would likely have lived.

Two weeks later, they reconvened at Margaret’s studio with remarkable findings.

Dr.

Freeman arrived with a folder thick with photocopied newspaper articles.

I found them, she said, spreading the papers across the table.

Jonathan Williams appears in the Chicago Defender starting in 1905.

He’s listed as an attorney handling civil rights cases, working with the city’s black legal community.

And Clara, she taught at Wendell Phillips High School and organized adult education programs.

The articles painted a picture of a couple who’d rebuilt their lives and continued their activism, but more quietly, more strategically.

Jonathan took cases challenging housing discrimination and employment barriers.

Clara wrote articles about education and helped establish libraries in black neighborhoods.

They’d learned to work within systems while still pushing for change.

But here’s what’s most remarkable, Dr.

Freeman continued, pulling out a specific article from 1920.

This is an interview with Jonathan published on the 16th anniversary of his wedding.

Listen to this.

When asked about his long marriage and partnership with his wife, Clara, Mr.

Williams reflected on their wedding day in Philadelphia, August 15th, 1904.

We stood for our photograph that morning, knowing violence awaited us, but we smiled anyway.

We refused to let hate steal our joy or dim our determination.

That photograph, wherever it now rests, represents more than our marriage.

It represents our people’s refusal to be intimidated into invisibility.

Margaret felt tears sting her eyes.

Jonathan had remembered the photograph had meant to him exactly what she’d sensed.

Evidence, testimony, resistance.

Robert had found census records in city directories.

They lived in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood from 1905 through at least 1940 when the trail goes cold.

They had two children, a son born in 1906 and a daughter in 1908.

The son became a doctor, the daughter a social worker.

The family was active in the NAACP, the Urban League, and various civil rights organizations.

When did they die? Margaret asked quietly.

Jonathan died in 1941.

Obituary says heart failure.

He was 69.

Clara lived until 1948.

She was 72.

Both obituaries mentioned their pioneering civil rights work in both Philadelphia and Chicago.

But neither obituary mentions the circumstances that drove them from Philadelphia or the courage they showed at their wedding.

Dr.

Freeman looked at the photograph with new appreciation.

This is the only visual record of that courage.

Samuel Chen captured something profound.

Not just a wedding portrait, but a moment of defiance, a refusal to be erased or intimidated.

And now, 54 years later, we can finally tell that story properly.

Margaret carefully packaged prints of the photograph along with all the documentation they’d gathered.

But what about their children or grandchildren? Shouldn’t they have this information? Have copies of the photograph? Robert nodded.

I’ve been trying to trace them.

The son, Thomas, died in Korea in 1951.

I found military records, but the daughter, Ruth, may still be alive.

She’d be about 50 now.

The last record I found was a 1955 Chicago city directory listing her as a social worker.

“We need to find her,” Margaret said firmly.

“She deserves to see this, to know the full story of her parents’ wedding day and their courage.

” It took another month of searching, but they finally located Ruth Williams Thompson, living in a modest apartment on Chicago Southside.

When Robert called to explain what they’d found, there was a long silence before Ruth spoke, her voice trembling.

My parents rarely spoke about their wedding day.

I knew they’d married in Philadelphia, knew they’d left because of threats, but they never shared details.

They said they wanted us to focus on the future, not the past.

But my mother kept one photograph from their wedding.

It hung in their bedroom for as long as I can remember.

Is that the photograph you found? I believe so, Margaret said, having been patched into the call.

Would you be willing to meet with us? We’ve discovered the full story behind that photograph, and we think you should know it.

Two weeks later, Ruth flew to Philadelphia.

She was a woman in her early 50s with her mother’s dignified bearing and her father’s intense gaze.

When Margaret showed her the photograph in her studio, Ruth broke down crying.

“That’s them,” she said through tears.

“That’s exactly how my mother kept the photograph displayed.

I never knew about the mirror, about what it showed.

I never knew my father was holding a gun.

I just thought it was a beautiful wedding portrait.

Margaret, Robert, and Doctor Freeman spent hours sharing everything they’d discovered.

Samuel Chen’s deliberate composition, the mob waiting outside, the community’s armed protection, the escape through underground railroad tunnels, the new life in Chicago.

Ruth listened to it all, occasionally touching the photograph as if connecting with her parents across the decades.

They protected us from this knowledge, Ruth said finally.

They wanted my brother and me to grow up without fear, without the weight of this violence.

But now I understand so much more.

Why they taught us to stand up for what’s right.

Why they insisted we get good educations.

Why they were so involved in civil rights work.

They were living out the defiance they showed in this photograph, refusing to let hate win.

She looked at Margaret with gratitude.

What will you do with this photograph and this research? With your permission, we’d like to exhibit it, Dr.

Freeman said.

The story needs to be told.

Too many people believe that black resistance to racism is a recent phenomenon.

That earlier generations simply accepted segregation and violence.

This photograph proves otherwise.

Your parents stood armed and dignified on their wedding day, refusing to be intimidated.

That’s a powerful historical lesson.

Ruth agreed with one condition.

That the exhibition include not just the wedding photograph, but also images and stories from Jonathan and Clara’s later life in Chicago, showing how their resistance continued and evolved.

She provided family photographs, her father’s legal papers, her mother’s teaching materials, letters, and documents that painted a complete picture.

The exhibition opened six months later at the African-American Museum in Philadelphia titled Standing Armed: Black Resistance and Dignity in the Progressive Era.

Margaret’s photograph of Jonathan and Clara’s wedding day served as the centerpiece with Samuel Chen’s deliberate composition explained in detail how the mirror captured both the public face the couple presented and the private reality they navigated.

The response was overwhelming.

Thousands of visitors came, many bringing their own family stories of resistance, survival, and dignity in the face of violence.

Educators used the photograph in classrooms.

Historians incorporated it into their research.

The image appeared in documentaries and textbooks, always with full context about what the mirror revealed and what the couple had survived.

Ruth attended the opening, standing before her parents’ photograph and telling visitors they wanted to be remembered for their love and their strength, not for the violence they faced.

This photograph shows both the threats they endured and the dignity they refused to surrender.

That’s their legacy.

Margaret stood nearby, watching people examine the photograph with new understanding.

Samuel Chen had been right to position that mirror to document not just the couple’s public dignity, but also the private reality they navigated.

The gun Jonathan held, the threatening figures visible through the window.

These details didn’t diminish their love, but emphasized their courage.

As the exhibition continued its run, Margaret received letters from descendants of other families who’d faced similar violence, who’d survived and resisted and built lives despite constant threats.

The photograph had become more than one couple’s story.

It was proof that resistance had always existed, that dignity had always been defended, that love had always required courage.

On the final day of the exhibition, Margaret returned to look at the photograph one last time before it was packed for its tour to other museums.

She studied Jonathan’s face, Clara’s determined smile, the hidden gun, the threatening shadows, all captured in Samuel Chen’s carefully composed frame.

You survived, she whispered, echoing the inscription on the back.

And now everyone knows how and why and at what cost.

Your courage is visible now, your resistance documented forever.

The photograph had waited 54 years to tell its full story.

But now that story would endure, teaching future generations that dignity and defiance had always walked hand in hand, that love had always required courage, and that sometimes the most revolutionary act was simply refusing to let fear steal your joy or dim your determination.

Jonathan and Clara had known that in 1904.

And now, thanks to a damaged photograph in an antique shop and a restoration expert who looked closely enough to see what the mirror revealed, the world knew it,

News

Pope Leo XIV SILENCES Cardinal Burke After He REVEALED This About FATIMA—Vatican in CHAOS!

A Showdown in the Vatican: Cardinal Burke Confronts Pope Leo XIV Over Fatima Revelations In a dramatic turn of events…

ARROGANT REPORTER TRIES TO HUMILIATE BISHOP BARRON ON LIVE TV — HIS RESPONSE LEAVES EVERYONE STUNNED When a Smug Question Turns Into a Public Trap, How Did One Calm Answer Flip the Entire Studio Against Its Own Host? A Live Broadcast, a Loaded Accusation, and a Moment of Brilliant Composure Now Has Millions Replaying the Exchange — Click the Article Link in the Comment to Watch the Scene Everyone Is Talking About.

Bishop Barron Confronts Hostile Journalist in a Live TV Showdown In a gripping encounter that captivated audiences, Bishop Robert Barron…

Angry Protesters Disrupt Bishop Barron’s Mass… His Response Moves Everyone to Tears

A Transformative Encounter: Bishop Barron’s Unforgettable Sunday Mass What began as an ordinary Sunday Mass at the cathedral took an…

Bishop Barron demands Pope Leo XIV’s resignation in fiery speech — world leaders respond

A Historic Confrontation: Bishop Barron Calls for Pope Leo XIV’s Resignation In an unprecedented turn of events, the Vatican finds…

Pope Francis leaves a letter to Pope Leo XIV before dying… and what’s written in it makes him cry.

The Emotional Legacy of Pope Francis: A Letter to Pope Leo XIV In a poignant moment of transition within the…

POPE LEO XIV BANS THESE 12 TEACHINGS — THE CHURCH WILL NEVER BE THE SAME AFTER THIS When Ancient Doctrine Is Suddenly Silenced, What Hidden Battle Is Tearing Through the Heart of the Vatican — and Why Are Believers Around the World Being Kept in the Dark? Secret decrees, quiet councils, and forbidden teachings now threaten to rewrite centuries of faith — Click the Article Link in the Comment to Discover What the Church Isn’t Saying.

Pope Leo XIV Challenges Tradition with Bold Ban on Twelve Teachings The Catholic Church stands on the brink of transformation…

End of content

No more pages to load