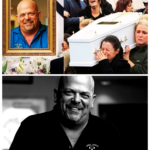

This 1904 Family Portrait Is Calm — Until the Child’s Face Reveals Something Odd

In the spring of 2024, antique photograph appraiser David Harrison received an unusual call from Dr.

Rebecca Matthews, curator of the Chicago History Museum.

The museum had recently acquired a large collection of early 20th century photographs from the estate of a prominent Illinois family, and several images had raised questions that required expert analysis.

“We have a 1904 family portrait that’s been troubling our research team,” Dr.

Matthews explained during their phone conversation.

At first glance, it appears to be a typical formal family photograph from that era.

But there’s something about one of the children in the portrait that doesn’t seem right.

Harrison, who had built his reputation on solving photographic mysteries and authentication puzzles, was intrigued.

He had spent 25 years examining vintage photographs and unusual details often revealed fascinating stories about the families and circumstances behind the images.

The Chicago History Museum occupied an impressive building on North Clark Street and Dr.

Matthews met Harrison in the museum’s research facility where the newly acquired collection was being cataloged.

The room contained dozens of photographs, documents, and personal items that had belonged to the Whitfield family.

One of Chicago’s prominent industrial families from the early 1900s, “The Whitfield collection spans from the 1890s through the 1920s,” Dr.

Matthews explained as she led Harrison to a particular photograph laid out on the examination table.

“Most of the images are straightforward family portraits and social gatherings, but this one has been puzzling our entire research staff.

” The photograph in question was an 8Q 10-in studio portrait mounted on heavy cardboard backing, typical of professional photography from 1904.

The image showed exceptional clarity and composition, indicating it had been taken by one of Chicago’s premier photography studios.

At first examination, the portrait appeared completely normal.

A well-dressed family of four posed in an elegant studio setting that reflected their social status and wealth.

The 1904 photograph depicted the Whitfield family in their finest formal attire positioned in the classical arrangement favored by wealthy Chicago families of that era.

The composition followed the established conventions of studio portraiture with each family member carefully positioned to create a harmonious and dignified presentation.

Mr.

Charles Whitfield, a distinguished gentleman in his early 40s, stood behind his seated wife, wearing an impeccably tailored dark suit with a silk vest and gold watch chain.

His posture conveyed the confidence and authority of a successful businessman, and his expression reflected the serious demeanor considered appropriate for formal portraits of the period.

Mrs.

Catherine Whitfield sat gracefully in an ornate chair.

Her elaborate dress featuring the intricate beadwork and lace details that indicated both wealth and refined taste.

Her hair was arranged in the fashionable Gibson girl style of 1904, and she wore jewelry that suggested the family’s considerable prosperity.

The couple’s two children completed the family grouping.

12-year-old Margaret stood beside her mother wearing a dress with sailor style collar that was popular for young girls of wealthy families while 8-year-old Thomas sat on a small stool near his father’s feet dressed in a formal suit with knee bridges and high stockings typical of boys clothing from that era.

The studio backdrop featured painted classical elements, marble columns and garden scenery that created an atmosphere of refinement and cultural sophistication.

The photographer had arranged the lighting to create even illumination across all four subjects, demonstrating the technical skill expected from Chicago’s most established portrait studios.

Harrison examined each element of the photograph methodically, noting the period appropriate clothing, jewelry, and studio props.

Everything appeared authentic and consistent with 1904 American portrait photography.

Yet, as Dr.

Matthews had indicated there was indeed something unusual about young Thomas that became apparent under closer scrutiny.

The boy’s face, while clearly that of a child, showed an expression that seemed oddly mature and knowing for someone of his age, an expression that didn’t quite match the innocence typically captured in children’s portraits from that era.

Harrison focused his professional magnifying equipment on young Thomas Whitfield’s face, studying the details that had troubled the museum’s research team.

What he observed was deeply unsettling and completely inconsistent with normal childhood development and behavior patterns of 1904.

The 8-year-old boy’s eyes held an expression of cold calculation that was profoundly inappropriate for a child of his age.

Rather than the innocence, curiosity, or even the formal seriousness expected in children’s portraits from that era, Thomas’s gaze conveyed an adult-like awareness and intensity that suggested experiences far beyond his years.

Most disturbing was the subtle but unmistakable expression around the boy’s mouth, a slight knowing smile that implied secret knowledge or satisfaction about something hidden from the other family members.

This expression contrasted sharply with the genuine familial warmth displayed by his parents and sister.

Dr.

Matthews joined Harrison at the examination table, pointing out additional details that the museum staff had noticed.

Look at his posture.

Compared to his sisters, she observed, Margaret shows the typical fidgeting and slight awkwardness you’d expect from a 12-year-old trying to hold still for a long exposure.

But Thomas appears completely comfortable and controlled, almost as if he’s performed for cameras many times before.

Harrison studied the contrast between the two children more carefully.

Margaret’s face showed the natural expressiveness of a young girl, slight nervous energy around her eyes, a genuine but somewhat forced smile, and the subtle signs of a child trying to meet adult expectations during a formal portrait session.

Thomas, however, displayed none of these normal childhood characteristics.

His composure was unsettling in its completeness, suggesting either exceptional training in adult behavior or exposure to experiences that had forced premature maturation.

Most troubling was the way Thomas’s eyes seemed to focus not on the camera, but slightly beyond it, as if he was looking at something or someone else in the studio during the portrait session.

This indirect gaze combined with his knowing expression created an impression that the boy was communicating with someone outside the frame, someone his family was apparently unaware of.

Harrison knew that understanding the context behind Thomas Whitfield’s disturbing expression would require extensive research into the family’s history and circumstances.

In 1904, he began by examining the museum’s acquisition, records to trace how the photograph collection had been obtained, and what documentation existed about the Whitfield family.

The collection had been donated to the Chicago History Museum by Eleanor Whitfield Carson, the great granddaughter of Charles and Catherine Whitfield.

According to her donation statement, the family photographs and documents had been stored in the attic of the family’s Lake Forest estate for decades before she discovered them while settling her grandmother’s estate.

Elellanar’s accompanying letter mentioned that her family had always been somewhat secretive about their early history in Chicago, particularly regarding events from the 1900s.

She noted that her grandmother had rarely spoken about her childhood and had seemed uncomfortable whenever old family photographs were displayed.

Harrison contacted Elellanar Whitfield Carson to request additional information about the 1904 portrait and the circumstances surrounding it.

During their phone conversation, Eleanor revealed troubling family stories that had been passed down through generations, but never fully explained.

“My grandmother Margaret, the girl in the photograph, used to say that something terrible happened to her brother Thomas when they were children.

” Eleanor explained.

She would never give details, but she always insisted that Thomas had been changed by some experience when he was very young.

Eleanor continued with more disturbing family.

Toué grandmother said that after 1904, Thomas was never the same child he had been before.

She claimed that adults started treating him differently, almost like they were afraid of him.

The family eventually sent him away to a private boarding school when he was only 10 years old.

These revelations suggested that the 1904 portrait had been taken during a significant transitional period in the family’s life, possibly documenting the aftermath of traumatic events that had profoundly affected young Thomas.

Harrison realized he needed to research Chicago newspaper archives and official records from 1904 to understand what had happened to the Whitfield family during that crucial year.

Harrison spent several days at the Chicago Public Libraries archives, searching through newspaper collections from 1904 for any mentions of the Whitfield family.

His research revealed that Charles Whitfield had been a prominent figure in Chicago’s industrial development, owning several manufacturing facilities that produced machinery for the city’s rapidly expanding infrastructure.

The Chicago Tribune archives from early 1904 contained several articles about labor disputes at Whitfield’s factories, including reports of unsafe working conditions and worker injuries that had resulted in public scrutiny of his business practices.

These articles portrayed Charles Whitfield as a successful but controversial businessman who prioritized profits over worker safety.

More significantly, Harrison discovered a series of articles from the Chicago Daily News in the summer of 1904 that reported on a criminal investigation involving the Whitfield family.

The headlines were shocking.

Prominent family under investigation.

Child witness in industrial accident case.

and a young boy’s testimony raises questions.

According to these newspaper reports, 8-year-old Thomas Whitfield had been present at one of his father’s factories during a catastrophic accident that killed three workers and injured several others.

The boy had apparently witnessed events that contradicted his father’s official account of the accident, creating a legal and ethical crisis for the family.

The most disturbing article published in August 1904 revealed that Thomas had provided testimony to investigators that implicated his father in deliberately ignoring safety warnings that could have prevented the fatal accident.

The boy’s account suggested that Charles Whitfield had known about dangerous conditions at the factory, but had refused to implement safety measures due to their cost.

What made Thomas’s testimony particularly troubling was the mature and detailed nature of his observations.

According to the newspaper reports, the 8-year-old had demonstrated an adult-like understanding of the industrial processes and safety procedures involved in the accident, leading investigators to question how a child could possess such sophisticated knowledge.

The final article in the series, dated September 1904, reported that the investigation had been quietly closed without charges being filed against Charles Whitfield, despite Thomas’s testimony.

The article suggested that political pressure and financial influence had prevented prosecution of the prominent businessman.

Harrison’s research into the 1904 factory accident revealed the traumatic events that had transformed young Thomas Whitfield from an innocent child into the disturbing figure captured in the family portrait.

Court records from the Cook County Archives provided detailed testimony about the incident that had claimed three lives and changed the Whitfield family forever.

The accident had occurred at Whitfield Manufacturing Company’s Southside facility on July 12th, 1904.

A steam boiler had exploded during the afternoon shift, killing three workers instantly and injuring five others with severe burns and crushing injuries.

The blast had been so powerful that it destroyed an entire section of the factory building.

According to witness testimony, young Thomas Whitfield had been visiting the factory with his father that day, supposedly to observe the manufacturing processes as part of his education about the family business.

The boy had been standing in his father’s office, which overlooked the factory floor when the explosion occurred.

What made Thomas’s presence significant was his account of conversations he had overheard between his father and the factory supervisor in the hours before the accident.

The 8-year-old had testified that he heard the supervisor warn Charles Whitfield about dangerous pressure readings in the boiler system and request permission to shut down operations for repairs.

Thomas’s testimony revealed that his father had refused to authorize the shutdown, stating that production deadlines were more important than worker safety concerns.

The boy had also overheard his father dismiss the supervisor’s warnings as worker excuses to avoid work.

Most damaging to Charles Whitfield was Thomas’s detailed account of his father’s reaction immediately after the explosion.

Rather than showing shock or remorse, the boy testified that his father had immediately begun discussing how to minimize the company’s legal liability and how to prevent the incident from damaging the family’s reputation.

Thomas had described watching his father calculate the financial cost of worker compensation payments while rescue efforts were still underway for the injured survivors.

This cold-blooded response to human tragedy had apparently been witnessed and understood by the 8-year-old, creating the mature and disturbing awareness that was now visible in his expression in the 1904 portrait.

The boy’s testimony had been so detailed and damaging that investigators had initially suspected he had been coached by adults seeking to harm Charles Whitfield’s business interests.

Further investigation into the court records revealed the extraordinary circumstances that had enabled 8-year-old Thomas Whitfield to provide such detailed and damaging testimony about his father’s role in the factory accident.

The boy’s account went far beyond what would normally be expected from a child witness, suggesting experiences that had forced premature maturation.

According to the transcripts, Thomas had been accompanying his father to the factory regularly.

For several months before the accident, supposedly as part of an informal education in business management.

During these visits, the boy had observed not only the manufacturing processes, but also the management discussions and decision-making that affected worker safety.

Thomas’s testimony revealed that he had witnessed previous incidents where his father had prioritized production schedules over safety concerns.

The boy described several occasions when workers had been injured due to unsafe conditions that Charles Whitfield had refused to address, and he had observed his father’s consistent pattern of minimizing responsibility for these incidents.

What made Thomas’s account particularly disturbing was his apparent understanding of the financial calculations behind his father’s decisions.

The 8-year-old had testified about overhearing conversations where Charles Whitfield discussed the costbenefit analysis of worker safety measures versus potential injury compensation payments.

The court records also revealed that Thomas had been present during meetings where his father and business associates had discussed strategies for avoiding legal liability when workers were injured.

The boy had absorbed these adult conversations and had developed an sophisticated understanding of how wealthy businessmen manipulated legal and political systems to avoid consequences for their actions.

Most troubling was Thomas’s testimony about his father’s instructions regarding what the boy should say if questioned about factory conditions.

Charles Whitfield had apparently attempted to coach his son to provide false testimony that would support the company’s position.

But Thomas had instead chosen to tell investigators the truth about what he had witnessed.

The boy’s decision to testify against his father’s interests had required a level of moral courage and independence that was extraordinary for an 8-year-old.

This experience had forced Thomas to confront adult realities about corruption, manipulation, and the abuse of power that most children never encounter.

Harrison’s research revealed that the Whitfield family’s response to Thomas’s testimony had been swift and devastating for the young boy.

Rather than supporting their son’s courage in telling the truth, Charles and Catherine Whitfield had treated Thomas as a traitor who had threatened the family’s social standing and financial security.

Private correspondence found in the family papers showed that Charles Whitfield had been furious about his son’s testimony and had blamed the boy for jeopardizing the family’s reputation.

In letters to his wife, Charles had expressed his belief that Thomas had been influenced by outside agitators who sought to damage his business interests.

Katherine Whitfield’s diary entries from late 1904 revealed her own distress about the situation, but her concern focused more on the family’s social embarrassment than on her son’s moral development.

She had written extensively about the difficulty of maintaining their position in Chicago society after Thomas’s testimony had been reported in the newspapers.

The family’s solution had been to isolate Thomas from potential future questioning and to remove him from situations where he might provide additional damaging information about Charles Whitfield’s business practices.

Within months of the factory accident investigation, the family had made arrangements to send Thomas to a private boarding school in Massachusetts.

The boarding school, according to the family correspondence, had been specifically chosen for its discretion and its willingness to accept students whose families preferred minimal contact with their children.

The school’s headmaster had assured the Whitfields that Thomas would receive proper education while being kept away from situations that might remind him of the events in Chicago.

Most heartbreakingly, the family papers revealed that Margaret Whitfield had been instructed not to discuss her brother with friends or family members.

The 12-year-old had been told that Thomas’s testimony had been the result of confusion and that the family needed to protect him by not encouraging him to discuss the factory accident.

The 1904 portrait had apparently been commissioned shortly before Thomas was sent away to boarding school, serving as a final family photograph before the boy’s exile.

The knowing expression captured in Thomas’s face reflected his understanding that his honesty had made him unwelcome in his own family.

Harrison’s investigation into Thomas Whitfield’s boarding school experience revealed the long-term consequences of the boy’s traumatic exposure to adult corruption and his family’s rejection of his moral courage.

Records from the Milbrook Academy in Massachusetts showed that Thomas had been enrolled as a special circumstances student whose family had requested minimal contact and reporting.

The school’s records indicated that Thomas had been an exceptional but troubled student who demonstrated unusual maturity and cynicism for his age.

His teachers had noted his advanced understanding of business and legal concepts, but they had also observed his difficulty forming normal friendships with children his own age.

One teacher’s report from 1906 described Thomas as a boy who has seen too much of the adult world’s capacity for deception and selfishness.

He approaches all relationships with awareness that suggests profound disillusionment with human nature.

The teacher had recommended counseling to help Thomas develop more age appropriate social skills and emotional responses.

However, the Whitfield family had specifically requested that the school avoid any psychological intervention that might encourage Thomas to discuss his experiences in Chicago.

They had insisted that the boy needed to forget the past and focus entirely on his academic development.

Thomas’s academic performance had been outstanding, particularly in subjects related to business law and industrial management.

By age 12, he had been reading college level texts on economics and corporate governance, demonstrating the precocious intellectual development that had enabled him to understand and testify about his father’s business practices.

But the school records also showed concerning behavioral patterns that reflected Thomas’ premature exposure to adult corruption.

He had been disciplined several times for manipulating other students and for demonstrating what teachers described as an adult-like capacity for deception and strategic thinking.

Most telling was a letter that Thomas had written to his sister Margaret in 1907 when he was 11 years old.

In the letter, he had described his understanding that their father’s wealth and social position were built on the suffering of workers, and he had expressed his belief that their family’s comfortable lifestyle was paid for with other people’s blood.

The letter revealed that Thomas’s experience as a child witnessed to industrial corruption had fundamentally altered his understanding of wealth, power, and moral responsibility in ways that would shape his entire adult life.

Harrison’s investigation reached its conclusion when he discovered Thomas Whitfield’s adult correspondence, which revealed how his childhood experience as a witness to industrial corruption had shaped his entire life philosophy and career choices.

Letters from the 1920s showed that Thomas had become a prominent labor rights attorney who dedicated his career to protecting workers from exactly the kind of exploitation he had witnessed at his father’s factory.

In a 1925 letter to a colleague, Thomas had written extensively about the 1904 factory accident and his decision to testify against his father’s interests.

He had described the experience as the moment when I learned that adults, even one’s own parents, could choose money over human life without any apparent moral struggle.

Thomas had explained that his disturbing expression in the 1904 family portrait reflected his realization that his testimony had made him an outsider in his own family.

He had understood even at age 8 that his honesty had threatened everything his parents valued more than truth or justice.

The adult Thomas had described his boarding school years as a period of intellectual development combined with emotional isolation.

He had learned to navigate adult social systems while maintaining the moral clarity that had led him to testify truthfully about the factory accident.

Most remarkably, Thomas’s correspondence revealed that he had used his inheritance from the Whitfield family fortune exclusively to fund legal representation for industrial workers injured in factory accidents.

He had viewed this as a form of justice for the three men who had died in his father’s factory and for the countless other workers who had suffered due to wealthy businessmen’s indifference to safety.

Thomas had never married or had children, apparently believing that his childhood experience had left him too damaged to form normal family relationships.

He had remained in contact with his sister Margaret throughout his adult life.

But he had never forgiven his parents for choosing their social reputation over moral responsibility.

The 1904 portrait with its capture of 8-year-old Thomas’s knowing and disturbing expression represented a moment when childhood innocence had been permanently destroyed by exposure to adult corruption.

The boy’s face revealed not just his understanding of what he had witnessed, but his realization that speaking the truth had made him unwelcome in his own family.

As Harrison prepared his final report for the Chicago History Museum, he reflected on how a single facial expression in an old photograph had revealed a story of moral courage, family betrayal, and the long-term consequences of childhood trauma.

The portrait was valuable not just as a historical artifact, but as evidence of how one child’s honesty had challenged a system of wealth and privilege that preferred comfortable lies to painful truths.

is.

News

This 1903 family portrait looks peaceful until you see what’s in the mirror. The discovery. The dusty attic of the old Victorian house in Salem, Massachusetts, held decades of forgotten memories. Margaret Chen, a professional estate appraiser, carefully stepped over creaking floorboards as she cataloged the belongings of the recently deceased Hartwell family patriarch. The autumn afternoon light filtered through a grimy window, illuminating cobwebs that danced in the disturbed air. just old furniture and documents up here,” she muttered to herself, making notes on her tablet. The Heartwell estate was substantial. “Three generations of wealth accumulated in this imposing house built in 1885. But it was the personal items that often held the most surprises. In a leather trunk beneath moth eataten quilts, Margaret’s fingers found something unexpected, a large, ornately framed family portrait. She lifted it carefully, surprised by its weight.

This 1903 Family Portrait Looks Peaceful — Until You See What’s in the Mirror This 1903 family portrait looks peaceful…

A 1904 portrait of a nurse appears serene—until you realize the child she holds hides a hidden truth Boston 2025. Rain tapped steadily against the windows of Children’s Hospital as curator Olivia Reeves carefully unfolded acid-free tissue paper from around a forgotten collection of photographs. The hospital’s upcoming 150th anniversary had prompted an exhaustive review of historical materials, bringing to light boxes of archival photographs untouched for decades. Olivia’s trained eye scanned each sepia toned image methodically. groups of stern-faced physicians, nurses in starched uniforms, hospital wards filled with iron beds. But one portrait stopped her cold. A young nurse, perhaps 25, sat perfectly composed in a wooden chair, her expression serene and professional. In her arms, she cradled an infant, swaddled in an intricately embroidered christening gown.

A 1904 portrait of a nurse appears serene—until you realize the child she holds hides a hidden truth Boston 2025….

Maria Shriver BREAKS Silence on Tatiana Schlossberg’s Shocking Terminal Cancer Diagnosis 😱💔 Maria Shriver, the beloved Kennedy matriarch, has finally broken her silence on the heartbreaking news that her niece, Tatiana Schlossberg, is battling a terminal cancer diagnosis. But the truth behind her announcement is far more than just a family’s grief—it’s a tale of secrets, betrayal, and untold struggles.

As Maria reveals the devastating news, she hints at dark family tensions that no one saw coming.

What is really happening behind closed doors? 👇

A Shattering Revelation: The Untold Story of Tatiana Schlossberg In the heart of New York City, Tatiana Schlossberg stood at…

Kennedy Family’s Dark Secrets Revealed as Tatiana Schlossberg’s Private Funeral Takes an Unexpected Turn 💔💀 The Kennedy family has always been the epitome of elegance and power, but at Tatiana Schlossberg’s private funeral, the cracks in their façade became glaringly obvious. Behind the closed doors of the somber gathering, a shocking revelation left everyone questioning what really happened to the once-glorious legacy of America’s most famous family.

As whispered voices filled the air and family members exchanged nervous glances, what was meant to be a mournful goodbye turned into a scandalous spectacle.

👇

Shadows of Legacy In the heart of New York City, beneath the weight of a somber sky, the air was…

End of content

No more pages to load