This 1902 wedding portrait looked beautiful — until experts realized the groom had hidden it

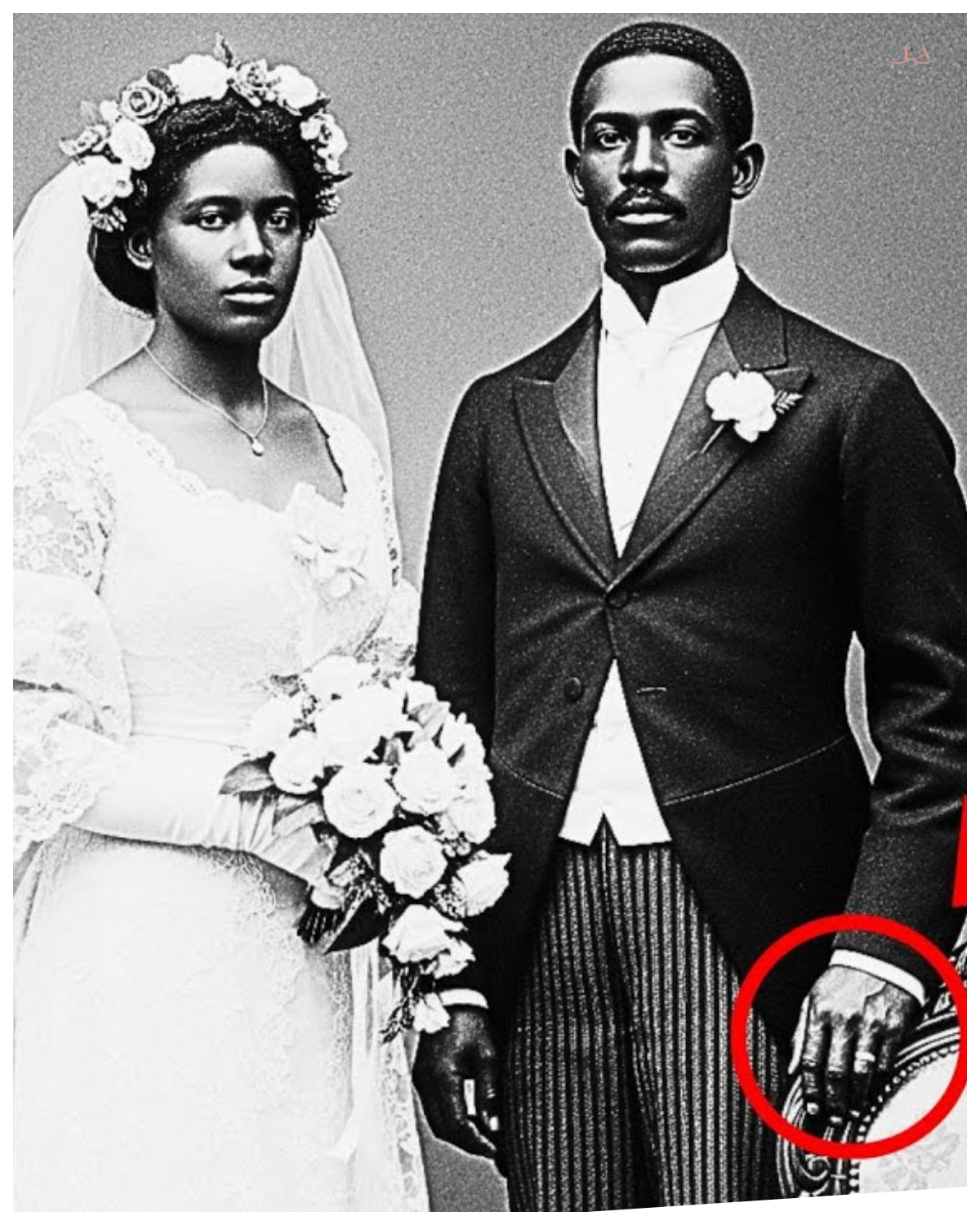

October 2019, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture receives a donation, a worn cardboard box containing a single wedding photograph from 1902.

The image shows a black couple in formal wedding attire standing before an elaborate painted backdrop in Richmond, Virginia.

The photograph is exceptional.

The bride wears an expensive white lace gown with leg of mutton sleeves, her hair adorned with silk orange blossoms.

The groom stands beside her in a black frock coat, a bineir pinned to his lapel.

The studio mark reads Reynolds and Sun, one of Richmond’s premier black photography studios, serving the elite of Jackson Ward.

Jackson Ward in 1902 was extraordinary.

Known as the Harlem of the South, it housed the wealthiest African-American community per capita in the United States.

Blackowned banks financed black businesses.

The neighborhood thrived with theaters, shops, and professional offices.

For a black couple to commission such an elaborate wedding portrait meant wealth, status, and social prominence.

Dr.

Dr.

Naomi Jenkins, a conservation specialist, begins the standard cataloging process.

Under magnification, she examines the photograph’s details, the quality of the lace, the composition, the lighting techniques typical of the era.

Then she notices something unusual.

The groom’s wedding band catches the light at an odd angle, revealing what appears to be an engraving on the inner surface.

She positions the photograph beneath a digital microscope camera.

The screen displays the image magnified 40 times.

The engraving is unmistakable.

Two initials intertwined in ornate Victorian script.

EM Dr.

Jenkins retrieves the documentation sleeve.

On the photograph’s reverse, written in elegant cursive, Florence Taylor, married October 12th, 1902.

The bride’s name is Florence Taylor, not EM.

The initials don’t match.

This discrepancy marks the beginning of an investigation that will span three years, uncover a pattern of crimes across five southern states and reveal the identities of seven women whose lives were systematically destroyed by one of the most successful con artists in early 20th century America.

A man who wore another woman’s ring to every wedding he performed.

The investigation requires historical context.

Marcus Peterson, senior archivist at the museum, joins the research.

Their first task is to verify the wedding’s existence beyond the photograph.

The Richmond Free Press, a black newspaper established in 1890, documented every significant event in the African-American community.

Its archives, now digitized, contain wedding announcements, obituaries, business openings, and social gatherings.

The October 12th, 1902 edition, contains a brief announcement.

Miss Florence Taylor, daughter of Mr.

Augustus Taylor, proprietor of Taylor’s Haberdashri on Second Street, was united in marriage to Mr.

Samuel Edison on Saturday, October 12th at First African Baptist Church.

The ceremony was attended by the finest families of Jackson Ward.

The groom’s name is Samuel Edison.

His initials would be S E, not EM.

A comprehensive search begins.

The team examines Richmond city directories, business registries, church membership roles, and property records from 1900 to 1903.

In this era, African-American communities maintained detailed documentation through churches, fraternal organizations, and mutual aid societies.

Professional men belong to multiple institutions.

Samuel Edison appears nowhere.

The search expands to Atlanta, Georgia, listed on the marriage certificate as Edison’s previous residence.

Atlanta in 1902 had one of the most vibrant black business communities in the South.

The Atlanta Life Insurance Company, founded in 1905, would become one of the most successful blackowned businesses in America.

Black newspapers like the Atlanta Independent documented the community’s prominent figures.

No Samuel Edison exists in any Atlanta records from this period.

The Library of Virginia archives contain the official marriage certificate handwritten in copper plate script.

Bride: Florence Elizabeth Taylor, age 22.

Daughter of Augustus Taylor.

Groom: Samuel James Edison, age 28.

Occupation.

Investor: Previous residence, Atlanta, Georgia.

The document is legal and properly filed, but the man it describes left no trace in any other historical record.

No business listings, no church membership, no property ownership, no evidence of existence before the wedding.

This pattern is significant.

In 1902, a successful black investor would have been notable, celebrated, documented.

His absence from all records suggests deliberate concealment.

The investigation shifts focus.

If Samuel Edison didn’t exist before October 1902, who was the man in the photograph, and why was he wearing a ring engraved with someone else’s initials? Understanding what happened requires understanding who Florence Taylor was? Her father, Augustus Taylor, represents a remarkable American story.

Born enslaved in Virginia in 1852, Augustus was freed as a child after the Civil War.

He received education at a Freedman’s Bureau School, institutions established by the federal government to educate formerly enslaved people.

By 1885, through decades of labor and savings, he opened Taylor’s Haberdashery on Second Street in Jackson Ward.

The business thrived.

Augustus sold men’s furnishings, hats, gloves, crevats, walking sticks to Richmond’s growing black professional class.

By 1900, Taylor’s habasherie was one of the most successful blackowned businesses in the city.

Augustus became a pillar of the community.

He served as deacon at First African Baptist Church, one of the oldest black congregations in Richmond.

He joined the Grand United Order of True Reformers, a black fraternal organization that operated its own bank, providing financial services to African-Americans excluded from white institutions.

Florence, his only child, received education in music and literature.

In the social hierarchy of black Richmond, she represented the next generation’s promise, the children of formerly enslaved people now living as educated, cultured citizens.

For Augustus Taylor, his daughter’s marriage carried immense significance.

It wasn’t merely personal.

It represented the culmination of everything reconstruction had promised.

Black families building wealth, establishing legacies, securing futures.

Summer 1902 editions of the Richmond Free Press reveal how Samuel Edison entered their lives.

July, Mr.

Samuel Edison of Atlanta was guest of honor at a reception hosted by Deacon Augustus Taylor.

Mr.

Edison spoke eloquently about investment opportunities in the New South and the importance of negro economic self-determination.

August Miss Florence Taylor was seen at Sunday services accompanied by Mr.

Samuel Edison who has recently relocated to Richmond to establish an investment firm serving the colored community.

Edison presented himself perfectly, a sophisticated black businessman from progressive Atlanta, someone who would help Richmond’s black elite grow their wealth.

Augustus introduced Edison throughout Jackson Ward’s tight-knit community, vouching for his character and credentials.

The wedding on October 12th, 1902 was a celebration of black achievement and possibility.

But within weeks, everything collapsed.

A November 1902 notice in the free press reads, “Mrs.

Florence Edison requests that friends refrain from calling as she is indisposed and requires privacy.

By January 1903, a legal notice appears.

Auction of household goods belonging to Mrs.

Florence Edison January 15th to satisfy debts.

3 months after her wedding, Florence was selling everything she owned.

Samuel Edison had disappeared.

A routine inquiry to the Library of Virginia produces an unexpected result.

An archivist responding to questions about Samuel Edison in other Virginia cities discovers another marriage certificate.

Norfolk, Virginia, June 3rd, 1901, 16 months before Florence’s wedding.

Groom Samuel Edison, age 27.

Occupation, investor, previous residence, Charleston, South Carolina.

Bride, Elizabeth Harris, daughter of Reverend Marcus Harris of Queen Street Baptist Church.

The same name, the same occupation, a different city, a different bride.

This discovery transforms the investigation.

Inquiries are sent to historical archives across the South.

Charleston, Atlanta, Savannah, Memphis, every major city with a substantial African-American population.

The responses reveal a systematic pattern.

Charleston, South Carolina, March 1900.

Samuel Edison married Eliza Monroe, daughter of a successful carpenter.

6 months later, court records show Eliza lost her home to creditors claiming Edison had borrowed against the property.

Savannah, Georgia.

October 1900, Samuel Edison married Marie Thompson.

Her father, a shipping clerk, invested his life savings in an investment firm Edison claimed to be establishing.

Both the money and Edison vanished by Christmas, Memphis, Tennessee, August 1901.

A man calling himself Samuel Edwards married Ruth Jackson, widow of a postal worker.

She lost her late husband’s death benefit nearly $2,000 within 3 weeks of the wedding.

Norfolk, Virginia, June 1901.

Samuel Edison married Elizabeth Harris.

Her father, a respected minister, was left financially ruined.

Richmond, Virginia.

October 1902.

Samuel Edison married Florence Taylor.

Seven cities, seven weddings, seven devastated women across a three-year period.

The profile is remarkably consistent.

Every victim was the daughter or widow of a successful black businessman, minister, or professional.

Every community had strong churches and social networks.

Every bride came from a family with property or significant savings.

The initials on the ring, em match the first known victim, Eliza Monroe of Charleston, March 1900.

The man who called himself Samuel Edison kept Eliza Monroe’s wedding ring and wore it hidden on his finger to every subsequent wedding.

While marrying Elizabeth Harris, Marie Thompson, Ruth Jackson, Florence Taylor, he wore Eliza’s ring.

This detail suggests more than simple theft.

It indicates a psychological dimension to the crimes.

A need to mark each new deception with evidence of the first.

Property records from each city reveal the same pattern.

Within weeks or months of each wedding, the bride signed over property or her family lost substantial money to creditors, claiming the husband had borrowed against assets.

Then the husband vanished, leaving behind debts, legal claims, and destroyed lives.

The scale of the operation becomes clear.

This wasn’t opportunistic crime.

It was systematic calculated predation targeting specific communities across the American South.

Dr.

Phyllis Grant, a historian at Virginia State University, specializing in postreonstruction African-American communities, joins the investigation.

Her expertise provides crucial context for understanding how these crimes were possible.

The period from 1900 to 1905 was critical for black Americans in the South.

Reconstruction had ended in 1877, and the Jim Crow system was solidifying.

African-Americans faced systematic exclusion from white economic institutions.

Banks refused loans to black applicants.

White businesses refused partnerships.

Insurance companies denied policies.

In response, black communities built parallel institutions.

Mutual aid societies pulled resources to help members during illness or death.

Fraternal organizations like the Masons and the Oddfellows provided social networks and financial assistance.

Blackowned banks like the True Reformers Bank in Richmond provided capital for businesses and mortgages.

These institutions functioned on trust.

Personal relationships mattered more than formal credit histories.

Church membership served as character reference.

A recommendation from a respected community leader carried enormous weight.

This system’s strength was also its vulnerability.

A person who could gain the trust of one prominent community member, a minister, a successful businessman, could quickly access the entire network.

William Hayes, the man behind the Samuel Edison identity, understood this perfectly.

Thomas Wright, a black private investigator hired by victim’s families, spent two years tracking the con artist.

His investigation published in the Baltimore Afroamerican in April 1904 revealed the true identity and methods.

Hayes was born in Philadelphia around 1874.

The son of a washerwoman, he received basic education, possibly through charitable institutions.

He worked as a clerk in various businesses, learning the language and presentation of finance and investment.

Hayes’s method was sophisticated.

He would arrive in a city claiming to come from another successful black community, Charleston, Atlanta, Memphis.

He carried forged letters of introduction from prominent black citizens of those cities.

These letters were nearly impossible to verify in an era without telephones or quick mail communication between cities.

He attended church services at the most prominent black congregations, making generous contributions to building funds in missionary societies.

He gave eloquent speeches about black economic advancement and self-determination using the rhetoric of racial uplift that resonated deeply in these communities.

He courted the daughter of the most prominent man he could access.

The wedding cemented his social position.

Then, using his wife’s property as collateral or exploiting his father-in-law’s business connections, he accumulated cash and transferable assets.

Finally, he manufactured a crisis, a business emergency requiring him to travel, a sick relative in another city, and disappeared.

The genius of the method, as Wright documented, was that Hayes weaponized hope.

These communities desperately wanted to believe in black success stories.

They wanted to support black businesses.

They wanted their daughters to marry educated, accomplished men.

Hayes turned these aspirations into vulnerabilities, systematically exploiting the very qualities that made these communities strong.

Thomas Wright’s background is remarkable.

Born in Baltimore in 1866, he worked for the Pinkerton Detective Agency in the 1890s.

One of the few black men hired by the organization, he left in 1899, frustrated by Pinkerton’s refusal to seriously investigate crimes against African-American victims.

Wright established his own detective agency in Baltimore, serving exclusively black clients.

By 1902, families of three victims, Eliza Monroe’s family in Charleston, Marie Thompson’s family in Savannah, and Elizabeth Harris’s family in Norfolk pulled resources to hire Wright.

His investigation lasted two years and covered six states.

Wright’s methods were meticulous.

He interviewed neighbors, church members, business associates, and anyone who’d interacted with Samuel Edison in each city.

He examined property records, business registrations, and court filings.

He tracked the pattern of fraudulent loans and suspicious creditors who appeared briefly, collected on debts, then vanished.

Wright’s case files preserved at the Maryland Historical Society document his findings.

The man’s real name was likely William Hayes, though even this might be false.

He was approximately 30 years old in 1902.

He spoke well, dressed impeccably, and had enough education to discuss literature, religion, and current events convincingly.

He knew scripture well enough to impress ministers and their congregations.

Hayes never used violence.

He relied entirely on social manipulation and legal documents.

In every case, the bride or her family voluntarily signed papers, loan agreements, property transfers, business contracts, believing they were helping establish Hayes’s investment firm, or supporting a family emergency.

The fraudulent creditors who appeared to collect debts were likely Hayes himself using different names or Confederates working with him.

JP Howard, who collected on the debt that took Florence Taylor’s house in Richmond, appeared in city directories for only one year.

Multiple creditors across different cities, showed the same pattern.

Wright tracked Hayes to Richmond in November 1903, arriving just weeks after he disappeared following Florence’s wedding.

Through interviews, Wright confirmed the same pattern.

Forged introductions, church attendance, generous contributions, eloquent speeches about racial advancement.

But Wright faced an insurmountable obstacle.

White law enforcement agencies in the south had no interest in investigating crimes against black victims.

When Wright presented his evidence to police in Richmond, Norfolk, Charleston, and other cities, he was dismissed or ignored.

Black communities, despite their internal organization, had no legal authority to pursue criminals across state lines.

Wright gathered comprehensive evidence of serial fraud spanning multiple states and had no mechanism to prosecute.

The Baltimore Afroamerican article from April 1904 published Wright’s findings and included a desperate plea.

Black newspapers across the South should share information, warned their communities, create an informal network to prevent further victims.

Some newspapers reprinted the warning.

Others added their own investigations of suspicious investors operating in their cities.

But coordination was limited by technology, geography, and resources.

The last confirmed sighting of William Hayes was in New Orleans in December 1905.

After that, the trail disappears completely.

He may have died young.

He may have left the South entirely.

Or he may have become sophisticated enough to avoid creating patterns investigators could track.

Thomas Wright continued his detective work until his death from pneumonia in 1918.

His obituary in the Afroamerican noted that he devoted much of his career to tracking confidence men who prayed on black communities, but had grown increasingly frustrated by the systemic barriers preventing justice for African-American victims.

William Hayes was never caught, never prosecuted, never punished for crimes that destroyed at least seven women’s lives and damaged entire communities ability to trust each other.

Florence Taylor’s life after the wedding reveals the devastating long-term impact of Hayes’s crimes.

Property records show that Florence owned a house on Clay Street in Richmond, a wedding gift from her father, legally deed to her name before marriage.

This was common practice among wealthy black families, an attempt to protect daughters property under Virginia law.

But by February 1903, just four months after the wedding, Florence voluntarily transferred the deed to JP.

Howard, who claimed Samuel Edison had borrowed $6,000 using the house as collateral.

This was an enormous sum, equivalent to approximately $200,000 today.

Howard filed legal papers demanding payment.

Florence, believing she was obligated to settle her husband’s debts signed over her property.

By March 1903, the house was sold.

Augustus Taylor’s habeddasherie began to decline.

Fewer advertisements appeared in the Richmond Free Press.

In 1905, the business moved to a smaller, cheaper location.

Augustus himself became ill.

His 1908 obituary states, “Mr.

Taylor suffered greatly in his final years following the disappearance of his son-in-law and the financial ruin that befell his daughter.

The habeddasherie closed within 6 months of his death.

Florence’s name appears in church membership roles at First African Baptist throughout the early 1900s, but she held no leadership positions in missionary societies or women’s groups, positions she would have naturally held as the daughter of a prominent deacon.

The social stigma was real.

Despite being a victim, Florence was viewed by some in the community as foolish, as someone who brought scandal to a respected family.

Victorian morality often blamed women for being deceived.

City directories track Florence’s declining circumstances.

After her father’s death, she moved frequently, different boarding houses, increasingly modest addresses.

The 1910 and 1920 census records list her occupation as seamstress, supporting herself through needle work like thousands of other black women.

She never remarried.

She never recovered her social position.

She never rebuilt what William Hayes had stolen.

Florence Taylor died on March 15th, 1932 at age 52.

Her obituary in the Richmond Free Press is brief.

Mrs.

Florence Taylor, formerly of this city, passed away at the Virginia Home for aged colored women.

Funeral services at First African Baptist Church.

No immediate family survives.

The Virginia Home for aged colored women was a charity institution for elderly black women without family or means.

Florence, once celebrated as one of Jackson Ward’s most promising young women, died alone, dependent on charity, 30 years after her life was destroyed.

The other victims of stories follow similar trajectories.

Eliza Monroe worked as a seamstress in Charleston until her death in 1935, never recovering financially or socially from the scandal.

Marie Thompson watched her father’s shipping business collapse after Hayes disappeared with investment capital.

She worked as a domestic servant in White Homes until her death in 1920.

Elizabeth Harris’s fate was perhaps the worst.

Her father, Reverend Marcus Harris, suffered a public breakdown after the scandal.

His congregation at Queen Street Baptist Church forced him to resign.

The shame destroyed his health.

Elizabeth lived in poverty, dying during the 1918 influenza epidemic at age 38.

Only one victim actively fought back.

Ruth Jackson in Memphis, after finding no help from white police, published a detailed warning in the Memphis Watchmen in January 1902.

Beware a man calling himself Samuel Edison or similar names, presenting as an investor from Atlanta or Charleston.

He’s well-dressed, educated, approximately 30 years of age.

He targets daughters of successful colored families, wins trust through churches, disappears after securing property or cash.

This man has left ruin in every city he visits.

But Ruth’s warning, published in January 1902, didn’t reach Richmond before Florence’s wedding in October 1902.

The informal network of black newspapers couldn’t disseminate information quickly enough across the geographic span of the South.

Seven women, seven destroyed lives, seven families financially and socially ruined, and the man responsible simply disappeared into history.

never facing consequences.

In 2220, Dr.

Grant posts information about the investigation on genealogy websites and academic forums, seeking descendants of the victims who might have family stories, documents, or photographs.

The response is unexpected.

Within weeks, several people contact the research team.

Kesha Washington, a social worker in Charleston, discovers she’s Eliza Monroe’s great great niece.

She grew up hearing vague family stories about a great aunt who’d married badly and lost everything, but no one discussed details.

The shame had been passed down through generations, even as the facts were forgotten.

“When Dr.

Grant contacted me,” Kesha explains in a recorded interview.

“I finally understood why my family had this shadow hanging over them, this unspoken tragedy that everyone knew about, but no one explained.

” Kesha searches her family’s papers and finds Eliza Monroe’s wedding photograph from March 1900.

The image shows a young woman with intelligent eyes and a gentle smile wearing a modest but elegant dress.

On her hand, clearly visible in the photograph, is the wedding ring engraved with her initials.

The ring William Hayes would wear hidden on his finger to six more weddings.

Other descendants come forward.

James Thompson from Savannah, great-grandson of Marie Thompson, brings his great-grandmother’s Bible with handwritten notes in the margins.

Desperate prayers asking God for help during the crisis after Hayes disappeared with her father’s money.

Angela Harris from Norfolk, descendant of Elizabeth Harris, shares a photograph of Reverend Marcus Harris in his clerical robes, standing proudly before Queen Street Baptist Church, taken before the scandal that would destroy his ministry and his health.

Each descendant describes the same experience, growing up with family shame attached to an ancestors name, whispered stories about foolishness or bad judgment, but never the full truth.

The victims had been blamed by their own communities and by their own descendants.

Learning that Eliza was targeted by a professional criminal who’d done this to multiple women, that completely changed how I understood my family history.

Kesha says, “She wasn’t naive.

She wasn’t foolish.

She was the victim of a sophisticated predator who exploited her community’s trust.

” The descendants agreed to participate in a public documentation of the crimes.

After 120 years of silence and shame, they want their ancestors remembered truthfully, not as cautionary tales about foolish women, but as victims of systematic exploitation.

The research team works with each family to gather documents, photographs, and oral histories.

The goal is to create a comprehensive historical record that honors the victims while exposing the methods used to exploit them.

This collaborative process reveals additional details.

Eliza Monroe had been an accomplished pianist who taught music to children in Charleston’s black community.

Marie Thompson had been active in church missionary societies.

Elizabeth Harris had been educated at Scotia Seminary, one of the premier institutions for black women’s education.

These weren’t naive or uneducated women.

They were accomplished, intelligent, active in their communities.

Exactly the kind of women a man like William Hayes would target because their families had the resources he wanted to steal.

The descendants also discover unexpected connections.

Several of the victim families had belonged to the same national organizations, the AM church network, the Grand United Order of True Reformers.

Their parents had attended the same conferences, read the same newspapers, participated in the same movements for black advancement.

They were part of a community that stretched across the South, bound by shared goals and mutual support.

William Hayes had exploited not just individual families, but the connective tissue of an entire generation’s efforts to build black prosperity and institutions.

Understanding this broader context transforms the project from a historical curiosity into something more significant, a documentation of how black communities were systematically victimized and how those communities strengths were weaponized against them.

In October 2022, the Smithsonian opens an exhibition titled The Ring: Deception, Trust, and Black Communities in the Jim Crow South.

The exhibition runs for 6 months and becomes one of the museum’s most visited special exhibitions.

The centerpiece is Florence Taylor’s wedding photograph, enlarged and displayed with detailed analysis of the ring’s engraved initials.

Beside it, hang photographs of the other six known victims, each woman’s story told with dignity and historical context.

One section of the exhibition documents William Hayes’s methods in detail, the forged letters, the church connections, the exploitation of mutual aid networks.

Adjacent panels explain why these methods were effective.

The systematic exclusion of black Americans from white institutions, forcing them to rely on personal networks and trustbased systems.

Another section honors Thomas Wright’s investigation, displaying pages from his case files in the Baltimore Afroamerican article that attempted to warn communities.

This section emphasizes the barriers Wright faced.

white authorities refusal to investigate, the lack of legal mechanisms for black communities to pursue interstate crimes, the limitations of early 20th century communication technology.

But the most powerful section features video interviews with descendants.

Kesha Washington stands before Eliza Monroe’s portrait, explaining how learning the truth changed her family’s understanding of their history.

James Thompson describes finding his great-grandmother’s Bible and reading her desperate prayers.

Angela Harris talks about her family’s loss when Reverend Harris was forced from his pulpit.

The exhibition attracts significant media attention.

The Washington Post runs a feature article.

NPR produces a podcast episode.

Academic journals publish papers analyzing the case as an example of how predatory crime exploited racial inequities in the early 20th century.

Visitors to the exhibition leave comments in a guest book.

Many are descendants of other black families from the Jim Crow era, recognizing similar stories in their own family histories, unexplained financial disasters, sudden losses of property, family members who married badly and were never discussed.

The exhibition sparks broader conversations about historical trauma, about how shame gets passed down through generations, even when the facts are forgotten, about the importance of documenting difficult histories alongside celebratory ones.

Dr.

Grant publishes a comprehensive book based on the research weaponized hope, confidence schemes, and black communities in the postreonstruction south.

The book examines William Hayes’s crimes within the larger pattern of predatory practices targeting African-Americans, fraudulent loan schemes, fake investment opportunities, land theft through legal manipulation.

The Descendants establish a scholarship fund in honor of the seven known victims.

The fund supports young black women studying finance, law, and business, fields that provide tools to recognize and prevent exploitation.

We can’t change what happened to our ancestors, Kesha Washington tells the Washington Post, but we can make sure their stories serve a purpose.

We can teach people to recognize these patterns.

We can honor them by turning this tragedy into education.

Marcus Peterson summarizes the investigation’s significance.

For more than a century, these women were forgotten or remembered only as cautionary tales.

Now they’re recognized as victims of systematic crime that exploited their community’s vulnerabilities.

That’s not just correcting the historical record.

That’s restoring dignity.

The exhibition closes in April 2023, but the online version remains permanently accessible on the Smithsonian’s website.

The descendants continue meeting annually, building relationships that their ancestors connections to each other as fellow victims first made possible.

William Hayes was never caught, never prosecuted, never punished.

But 120 years after his crimes, the women he victimized are finally remembered truthfully.

The communities he exploited understand how he manipulated their trust and his name is permanently attached to his crimes in the historical record.

That, as Dr.

Naomi Jenkins reflects, is a form of justice.

Late, incomplete, but real nonetheless.

The investigation doesn’t end with the exhibition.

In 2023, additional information emerges that provides unexpected closure to one part of the story.

A genealogologist in Philadelphia named Robert Hayes contacts the research team.

He’s been tracing his family history and believes he may be related to William Hayes.

His great great-randfather was named William Hayes, born in Philadelphia in the 1870s, who disappeared from family records around 1898.

Robert shares a photograph from approximately 1896.

The man in the image is young, perhaps 22, clean shaven, and serious looking.

But the facial structure, the eyes, the set of the shoulders, it matches the man in Florence Taylor’s wedding photograph 6 years later.

DNA testing isn’t possible without remains, but historical documents support the connection.

Birth records, census data, city directories, all align with the William Hayes that Thomas Wright identified in 1904.

Learning this about my ancestor was difficult, Robert tells the camera during a recorded interview.

But it’s important to face these truths.

I can’t undo what he did, but I can acknowledge it and support the descendants of his victims.

Robert contributes to the scholarship fund and helps provide additional context about William Hayes’s early life in Philadelphia.

The information fills gaps in the historical record, though it doesn’t explain why Hayes chose this particular path of predatory crime.

The final piece of the investigation focuses on Florence Taylor herself.

Naomi and Marcus obtain permission to access the archives of First African Baptist Church in Richmond.

In the church’s records from 1930, two years before Florence’s death, they find something unexpected.

A note in the church secretary’s handwriting.

Florence Taylor donated her wedding photograph to the church archives, asking that it be preserved as a reminder that even beautiful things can hide painful truths.

She hopes that future generations might learn from what happened to her.

Florence herself had wanted the photograph preserved.

She had understood its value as historical evidence, even though looking at it must have caused her pain.

That changes everything.

Naomi reflects.

Now, Florence wasn’t passive about what happened to her.

She actively tried to turn her tragedy into a warning for others.

The photograph being donated to the museum wasn’t random.

It was following Florence’s own wishes.

This discovery reframes the entire investigation.

The photograph’s journey from Florence’s possession to the church archives to the Smithsonian wasn’t accidental.

Florence had set this process in motion, hoping that someday someone would look closely enough to see what she’d seen too late.

The truth hidden beneath the beautiful surface.

The research team returns to Richmond and locates Florence’s grave in Evergreen Cemetery, a historically black cemetery where many of Jackson Ward’s residents were buried.

Her gravestone is simple, worn by weather, marked only with her name and dates.

With permission from the church and the cemetery, they install a new historical marker near her grave.

The marker tells Florence’s story truthfully, not as a cautionary tale about foolishness, but as a record of systematic victimization and resilient dignity.

The marker reads Florence Elizabeth Taylor, 1880 1932.

Daughter of Augustus Taylor.

Florence was one of seven known victims of confidence man William Hayes who used the alias Samuel Edison to target prominent black families across the South from 1900 to 1905.

Despite losing her home, social position, and financial security, Florence maintained her dignity and her faith.

She donated her wedding photograph to First African Baptist Church, hoping future generations would learn from her experience.

Her courage and preserving evidence of her own tragedy made this historical investigation possible.

Similar markers are installed in Charleston for Eliza Monroe, in Norfol for Elizabeth Harris, and in Savannah for Marie Thompson.

The descendants attend each installation, creating ceremonies that honor their ancestors and educate their communities.

The investigation concludes with a symposium at Virginia State University in March 2024.

Historians, criminologists, genealogologists, and descendants gathered to discuss the broader implications of the case.

Dr.

Grant presents research showing that confidence schemes targeting black communities were widespread in the early 20th century, though most went undocumented.

White controlled police and courts rarely investigated these crimes, and black communities warnings to each other were limited by technology and geography.

Professor James Morrison discusses how Hayes’s methods parallel modern financial fraud targeting vulnerable communities, predatory lending, fake investment schemes, romance scams that exploit trust and hope.

The symposium concludes with Kesha Washington addressing the audience.

Our ancestors weren’t foolish, they were hopeful.

They were building futures in a society designed to prevent them from succeeding.

When someone came along who seemed to represent what they were working toward, black success, black business, black prosperity, they wanted to believe.

William Hayes weaponized that hope.

Understanding that isn’t just about the past.

It’s about recognizing how these patterns continue.

How people still exploit communities aspirations and trust.

That’s why this history matters.

The wedding photograph that started the investigation remains on permanent display at the Smithsonian.

Visitors still pause before it, studying the bride’s proud expression, the groom’s confident smile, and the barely visible engraving on the ring that revealed everything.

Florence Taylor’s hope was realized.

Future generations did learn from what happened to her.

The photograph she preserved became the key to uncovering a pattern of crimes, restoring dignity to seven women, and teaching lessons that remain relevant more than a century later.

In the end, this is the power of historical investigation.

Not just discovering facts about the past, but understanding how those facts connect to the present, how patterns repeat, how truth can be obscured by beautiful surfaces, and how justice, even when delayed by 120 years, still matters.

The mystery of the wrong initials on a wedding ring became a story about trust, community, exploitation, resilience, and the long path toward acknowledging difficult truths.

And it all began with one photograph, one careful examination, and one woman’s determination that her tragedy should serve a purpose beyond the pain it caused

News

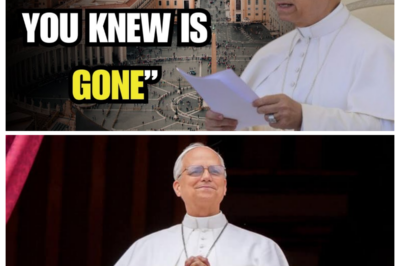

Pope Leo XIV SILENCES Cardinal Burke After He REVEALED This About FATIMA—Vatican in CHAOS!

A Showdown in the Vatican: Cardinal Burke Confronts Pope Leo XIV Over Fatima Revelations In a dramatic turn of events…

ARROGANT REPORTER TRIES TO HUMILIATE BISHOP BARRON ON LIVE TV — HIS RESPONSE LEAVES EVERYONE STUNNED When a Smug Question Turns Into a Public Trap, How Did One Calm Answer Flip the Entire Studio Against Its Own Host? A Live Broadcast, a Loaded Accusation, and a Moment of Brilliant Composure Now Has Millions Replaying the Exchange — Click the Article Link in the Comment to Watch the Scene Everyone Is Talking About.

Bishop Barron Confronts Hostile Journalist in a Live TV Showdown In a gripping encounter that captivated audiences, Bishop Robert Barron…

Angry Protesters Disrupt Bishop Barron’s Mass… His Response Moves Everyone to Tears

A Transformative Encounter: Bishop Barron’s Unforgettable Sunday Mass What began as an ordinary Sunday Mass at the cathedral took an…

Bishop Barron demands Pope Leo XIV’s resignation in fiery speech — world leaders respond

A Historic Confrontation: Bishop Barron Calls for Pope Leo XIV’s Resignation In an unprecedented turn of events, the Vatican finds…

Pope Francis leaves a letter to Pope Leo XIV before dying… and what’s written in it makes him cry.

The Emotional Legacy of Pope Francis: A Letter to Pope Leo XIV In a poignant moment of transition within the…

POPE LEO XIV BANS THESE 12 TEACHINGS — THE CHURCH WILL NEVER BE THE SAME AFTER THIS When Ancient Doctrine Is Suddenly Silenced, What Hidden Battle Is Tearing Through the Heart of the Vatican — and Why Are Believers Around the World Being Kept in the Dark? Secret decrees, quiet councils, and forbidden teachings now threaten to rewrite centuries of faith — Click the Article Link in the Comment to Discover What the Church Isn’t Saying.

Pope Leo XIV Challenges Tradition with Bold Ban on Twelve Teachings The Catholic Church stands on the brink of transformation…

End of content

No more pages to load