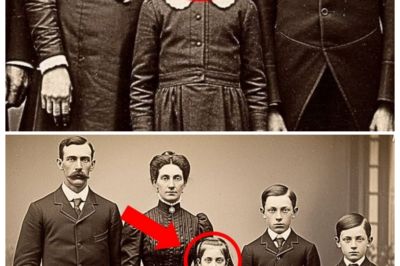

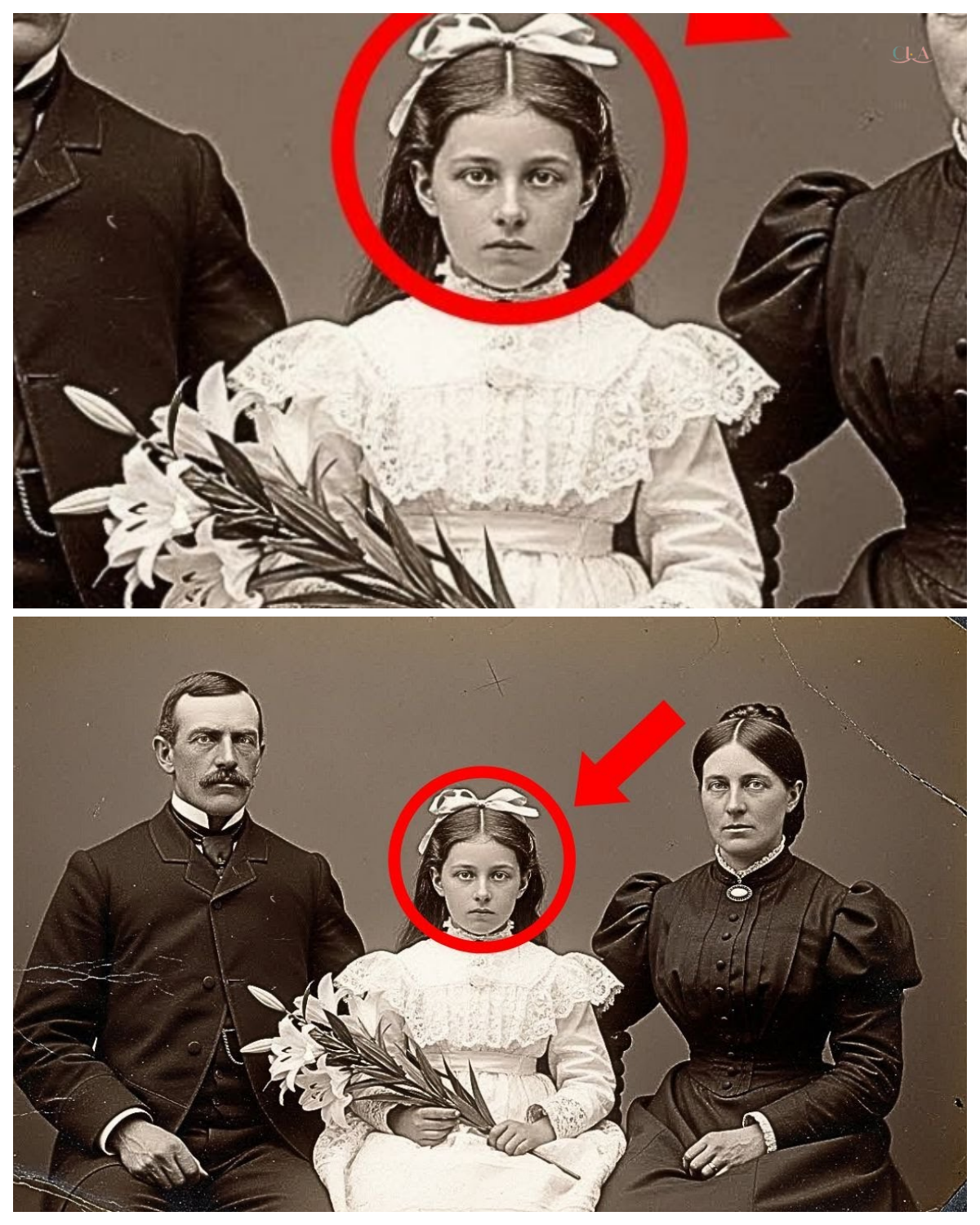

This 1901 studio portrait looks normal — until experts zoomed in on the child’s eyes

Dr.Sarah Brennan’s hands trembled slightly as she adjusted the highresolution scanner over the faded photograph.

The basement archive of the Boston Heritage Museum was cold, smelling of old paper and preservation chemicals.

She had been cataloging donated Victorian photographs for 3 weeks now, and most had been unremarkable.

Stiff portraits of forgotten families, their stories lost to time.

This one seemed no different at first glance.

A studio portrait dated 1901, stamped on the back with the name Whitmore Photography Studio, Lawrence, Massachusetts.

A well-dressed couple stood rigid, the man’s hand on his wife’s shoulder.

Between them sat a small girl, perhaps 6 years old, in a white-laced dress with ribbons in her dark hair.

The child’s hands were folded neatly in her lap, holding a small bouquet of white liies.

Sarah began the scanning process, watching as the digital image appeared on her computer screen in extraordinary detail.

She zoomed in to check the resolution, starting with the parents faces.

The father’s expression was stern, his jaw clenched.

The mother’s eyes were rimmed with red, her mouth a thin, painful line.

Then Sarah moved to the child’s face and her breath caught.

The girl’s eyes were wrong.

They were open, staring directly at the camera, but there was an unmistakable emptiness in them.

The pupils were dilated far beyond what the studio lighting would require.

The skin had an odd waxy quality that the photographer had tried to soften with careful posing and shadows.

Sarah leaned closer to her screen, her heart pounding.

She had studied Victorian photography extensively during her graduate work.

She knew what she was looking at.

“Oh, God,” she whispered to the empty room.

“She’s dead.

” Postmortem photography had been common in the Victorian era, a final chance to capture the image of a loved one, especially a child, taken too soon.

But there was something else here, something that made Sarah’s trained eye pause.

She zoomed in further on the child’s dress, on the flowers, on the careful positioning of the small, lifeless hands.

The parents anguish was palpable, even through the century old photograph.

This wasn’t just a memorial portrait.

This was a family destroyed by something frozen in their darkest moment.

Sarah pulled out the documentation that had come with a donated collection.

There had to be more to this story.

There had to be a name, a record, something that would tell her who this little girl was and what had taken her life.

She had no idea that this single photograph would consume the next 6 months of her life.

Sarah spent the entire weekend thinking about the photograph.

Monday morning, she arrived at the museum an hour early, clutching a coffee in her research notebook.

The image had been haunting her, the parents devastation, the child’s unseeing eyes, the careful staging that spoke of unbearable grief.

She pulled up the digital file and began examining every detail.

The photographers stamp on the back read, Whitmore Photography Studio, 147 Essex Street, Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1901.

That was her starting point, Lawrence.

Sarah typed the name into her computer.

a milltown north of Boston built along the Marramac River.

In 1901, it had been one of the largest textile manufacturing centers in the world.

Its massive brick mills employing thousands of immigrant workers, Irish, Italian, French, Canadian, Polish.

She called the Lawrence Public Library and spoke with a reference librarian named Thomas.

I’m researching a photograph from 1901, she explained, from the Whitmore Photography Studio on Essex Street.

Do you have any city directories from that period? We have an extensive local history collection, Thomas said warmly.

I can pull the 1901 city directory and check for Whitmore.

Can you hold? Sarah waited, drumming her fingers on her desk.

Through her office window, she could see tourists beginning to arrive at the museum entrance.

Found it.

Thomas came back on the line.

James Whitmore, photographer, studio at 147 Essex Street, just as you said.

He was in business from 1895 to 1908.

Is are there any records of his clients, customer logs, anything like that? Not that we have here.

But Thomas paused.

If the family who commissioned the photograph lived in Lawrence, there might be other records.

Birth certificates, death certificates, cemetery records.

The Lawrence History Center has extensive vital records.

Do you have any names? That’s what I’m trying to find, Sarah admitted.

Back at her desk, she examined the photograph again with fresh eyes.

Victorian photographers sometimes included small details that could provide clues.

The wallpaper pattern might indicate which studio room was used.

The style of furniture could suggest a date range.

Even the way the subjects were dressed could reveal social class.

Then she saw it on the mother’s dress, partially hidden by shadow, but visible when she enhanced the contrast.

A small brooch oval-shaped with what appeared to be an engraved pattern.

Sarah zoomed in as far as the resolution would allow.

It looked like initials, two letters intertwined in the Victorian style.

She squinted at the screen.

M and possibly R.

Or was it H? It wasn’t much, but it was something.

3 days later, Sarah drove north on Interstate 93 toward Lawrence.

The November morning was gray and cold, frost still clinging to the bare trees along the highway.

She had made an appointment at the Lawrence History Center, and her passenger seat was filled with printouts and notes.

The history center occupied a renovated mill building overlooking the Marramac River.

Inside, the smell of old paper and binding glue reminded Sarah of every archive she had ever worked in.

A young archist named Elena greeted her with enthusiasm.

Victorian post-mortem photography,” Elena said as she led Sarah to a research room.

“That’s a fascinating but heartbreaking field.

Let me show you what we have for 1901.

” Elena wheeled out a cart stacked with leatherbound volumes.

“These are death certificates from Lawrence, organized by year.

1901 is split into four volumes, one for each quarter.

If the child died in Lawrence, and the family had the means to commission a studio portrait, there should be a record.

” Sarah opened the first volume, running her finger down the columns.

names, dates, causes of death, ages, so many children.

She had known intellectually that infant and child mortality had been high in 1901, but seeing page after page of deaths, children under five, under two, under one year, made it visceral and real.

“What am I looking for?” she murmured.

“You said the photograph shows a girl around 6 years old, well-dressed in a studio portrait,” Elena said, sitting beside her.

That suggests a family with some means, not wealthy, but comfortable enough to afford a professional memorial.

Look for girls aged 5 to 7, and pay attention to the cause of death.

Sarah turned the pages slowly.

January, February, March.

Then, near the end of the first quarter, she found a cluster of entries that made her pause.

Elena, look at this.

From late March through early April 1901, the cause of death column showed the same word repeated over and over.

Dtheria.

Four children on March 28th, six more on March 30th, three on April 1st.

An outbreak, Elena said softly.

God, it must have swept through the neighborhood like wildfire.

Sarah’s heart was racing now.

She scanned the names.

Mary Oconor, age four.

Jeppe Romano, age three.

Katherine Murphy, age seven.

And then here she breathed.

Rose Hartley, age six.

Date of death, March 31st, 1901.

Cause dtheria.

Parents William and Margaret Hartley.

M and H on the brooch.

Margaret Hartley.

Sarah had found her name.

Sarah photographed the death certificate with her phone, her hands shaking slightly.

Rose Hartley.

Finally, the little girl had a name.

But a death certificate was just the beginning.

It told her when Rose died and what killed her, but nothing about who she had been or why her death was memorialized in that haunting photograph.

Elena was already pulling additional records.

If the Hartley’s lived in Lawrence in 1901, there should be more documentation.

Let me check the city census and property records.

While Elellanena worked, Sarah studied Rose’s death certificate more carefully.

The address listed was 45 Jackson Street.

The informant, the person who reported the death, was William Hartley, listed as mill worker.

No specific mill was mentioned, but in Lawrence in 1901, that could mean any of the massive textile operations that dominated the city.

Found them, Ellena called out.

The 1900 census shows William Hartley, age 29, born in England.

Occupation loom operator.

His wife Margaret, age 27, born in Massachusetts to Irish parents.

And Rose, age five at the time of the census.

They were living at the same Jackson Street address.

Sarah pulled out her notebook.

Loom operator.

So they were workingass, but he had a skilled position.

That fits with being able to afford a studio portrait.

Elena nodded.

The big mills paid relatively well for skilled work, but Jackson Street.

She pulled up a historical map on her computer that was in the immigrant neighborhood close to the mills.

Densely packed tenement houses, poor sanitation, exactly the kind of place where disease could spread rapidly.

The map showed Jackson Street as a short block lined with three-story wooden tenementss, each building housing multiple families.

Sarah could picture it.

Narrow rooms, shared hallways, children playing together in the cramped spaces.

One sick child could infect dozens of others within days.

Do you have any information about the dtheria outbreak itself? Sarah asked.

Newspaper articles, public health records.

We have the Lawrence Daily Eagle on microfilm going back to 1890.

Elena was already moving toward the micrfilm readers.

Let me pull March in April 1901.

They threaded the film and began scrolling through the pages.

The Eagle had been a daily paper, eight pages of local news, advertisements, and social notices.

Sarah’s eyes adjusted to reading the old type face as headlines flickered past.

Then on March 29th, 1901, the headline jumped out at her.

Dtheria claims four more children.

Outbreak in Jackson Street district spreads.

Sarah leaned closer to the screen, her pulse quickening.

The article began, “The dtheria epidemic that has terrorized families in the Jackson Street district claimed four more young victims yesterday, bringing the death toll to 11 children in the past 2 weeks.

” She was beginning to understand the world that Rose Hartley had lived and died in.

Sarah spent the next four hours reading through microfilm, printing every article that mentioned the dtheria outbreak.

Elena brought her coffee and sandwiches, sensing that the curator had fallen down a research rabbit hole and wouldn’t surface willingly.

The story that emerged from the yellowed newspaper pages was devastating.

The outbreak had begun in mid-March 1901, first appearing in the crowded tenement district near the mills.

The initial cases were dismissed as sore throats, common enough in the cold, damp New England spring.

But within days, children began dying.

City health officer warns of dtheria epidemic, declared the March 24th headline.

Parents urged to keep children home from school.

The article explained that dtheria attacked the throat, creating a thick gray membrane that could suffocate its victims.

Children were especially vulnerable.

The disease spread through close contact, sharing cups, coughing, even speaking.

In the cramped tenementss where multiple families shared single outouses and water pumps, containment was nearly impossible.

Sarah found an article from March 27th that made her chest tighten.

St.

An’s Parish to hold special services.

Father Donnelly comforts grieving families.

The list of children who had died was printed in the next column.

Sarah scanned the names and there it was.

Rose Hartley, daughter of William and Margaret Hartley, age 6, died March 31st at the family home on Jackson Street.

But it was the article from April 3rd that changed everything.

Health department investigates Milwater Supply.

Source of outbreak questioned, Sarah read with growing intensity.

City health inspectors had discovered that the water pump serving the Jackson Street tenementss drew from a well that was contaminated by seepage from a nearby outhouse.

The families living there, most of the mill workers, had been drinking tainted water for months.

The outbreak, the article suggested, might have been preventable.

Elena Sarah said looking up from the screen, this wasn’t just a random tragedy.

This was a failure of public health, of city infrastructure.

These families were living in conditions that guaranteed disease.

Elena came over to read the article.

That was true of most milltowns in this period.

The companies built the mills and the tenementss as quickly and cheaply as possible.

Workers health wasn’t a priority.

Sarah thought of the photograph.

William Hartley’s clenched jaw, Margaret’s red rimmed eyes.

They weren’t just grieving parents.

They were parents whose child had died from a preventable disease in conditions created by industrial greed and municipal neglect.

She needed to know more.

She needed to understand who Rose had been, what her short life had been like, and why her parents had chosen to memorialize her in that particular way.

“Are there any church records from that period?” Sarah asked.

St.

Anne’s parish that was mentioned in the article.

Ellena smiled.

“Now you’re thinking like a historian.

Let me make a call.

” St.

Anne’s church still stood on Havill Street, a massive brick structure with a tall bell tower visible from blocks away.

Sarah parked in front of the church on a cold Thursday afternoon, clutching a folder with copies of everything she had found so far.

Father Michael Riley, the current pastor, met her in the church office.

He was in his 60s with kind eyes and the patient manner of someone who had spent decades listening to people’s stories.

You mentioned on the phone you’re researching the 1901 diptheria outbreak, he said, gesturing for Sarah to sit.

That was before my time, obviously, but I know the story.

It’s part of the parish’s history, one of our darkest chapters.

I’m specifically trying to learn about one family, Sarah explained, showing him the photograph on her laptop.

William Margaret and Rose Hartley.

Rose died on March 31st, 1901.

They lived on Jackson Street.

A Father Riley studied the image, his expression somber.

Postmortem photography.

I’ve seen a few of these in our archives.

It was the only way most families could afford to have a photograph of their child.

He paused.

Come with me.

We have baptism, marriage, and burial records going back to the church’s founding in 1875.

He led Sarah down a narrow staircase to the church basement where rows of metal shelves held leatherbound record books.

Father Riley pulled out a volume labeled burials 1900 1905 and set it on a reading table.

“Let me help you look,” he offered.

They found Rose’s burial record within minutes.

The entry was brief but precise.

“Rose Katherine Hartley, born June 12th, 1894, died March 31st, 1901.

Buried April 3rd, 1901 at Immaculate Conception Cemetery.

Cause of death, dtheria service conducted by Father Patrick Donnelly.

But it was the notation at the bottom that caught Sarah’s attention.

Buried with 14 other children from the parish, victims of the Jackson Street outbreak.

14 children, Sarah whispered.

From just this one parish, Father Riley nodded grimly.

And St.

Ans was only one of several Catholic churches serving the immigrant communities.

The outbreak killed more than 30 children total in about 3 weeks.

It devastated entire neighborhoods.

He pulled out another volume.

Let me show you something else.

This book contained baptism records.

Father Riley flipped to 1894 and found Rose’s baptism.

June 19th, 1894, one week after her birth.

Parents, William Hartley and Margaret O’.

Sullivan Hartley.

Godparents, Thomas O’.

Sullivan and Katherine Murphy.

Her mother’s family was Irish.

Sarah noted.

O Sullivan.

And look, one of the godparents was Katherine Murphy.

Father Riley checked the burial records again.

Katherine Murphy, age seven, died March 28th, 1901.

Dtheria.

Sarah felt a chill.

Rose’s godmother had died just three days before Rose herself.

These weren’t just statistics in a newspaper.

These were interconnected families, neighbors, godparents, and godchildren, all watching their children die within days of each other.

Is there any way to find out more about the Hartley’s personally? Sarah asked.

What they were like, how they coped? Father Riley considered.

Father Donnelly kept detailed journals.

They might still be in the archives.

Let me see what I can find.

Father Riley returned 20 minutes later carrying a wooden box filled with small clothbound notebooks.

Father Donny’s journals, he said, setting the box on the table with reverence.

He was the parish priest from 1898 to 1912.

He wrote in these almost every day.

Visits to parishioners, baptisms, funerals, his own reflections on parish life.

Sarah’s hands trembled as she opened the first journal.

The handwriting was small and precise.

The entries dated and organized.

She flipped to March 1901.

The early March entries were routine.

Lenton services, confessions, a wedding on March 9th.

Then on March 18th, the tone shifted.

Visited the Murphy family on Jackson Street today.

Their daughter Catherine is gravely ill with what appears to be dtheria.

Mrs.

Murphy is beside herself with worry.

I’ve seen three other cases in the neighborhood this week.

I fear we are facing an outbreak.

Sarah read on, her heart sinking with each entry.

March 22nd, the dtheria spreads like wildfire.

Seven children seriously ill.

I have spent the day going from house to house administering last rights.

March 28th, Katherine Murphy died this morning.

I stood with her parents as she took her last breath.

She was only 7 years old.

Then on March 31st, Sarah found what she was looking for.

Today I lost young Rose Hartley, the daughter of William and Margaret, 6 years old, with her whole life ahead of her.

I had baptized her myself in 1894, held her in my arms when she was just days old.

Now I have held her mother as she wept over the child’s body.

Margaret Hartley is broken.

She told me Rose was a bright, happy girl who loved to help her mother with the younger children in the tenement, who sang in church, who dreamed of learning to read and write properly.

William is silent in his grief, but I can see the rage in his eyes.

He knows, as I know, that this death was preventable.

The contaminated water, the overcrowded housing, these are sins of greed and neglect.

Tomorrow I will conduct Rose’s funeral service.

It will be the fourth child’s funeral I have performed this week.

I’m running out of words to comfort these parents.

What can I say? That God has a plan.

That their children are in a better place.

These feel like empty platitudes in the face of such senseless loss.

Sarah wiped her eyes.

The entry continued.

William asked me about memorial photographs.

He has saved money, and he wants Rose remembered, not as she was in death, pale and struggling for breath, but as a beloved daughter, dressed in her Sunday best, held between her parents one final time.

I gave him the name of James Whitmore, the photographer on Essex Street, who has done dignified work for other bereaveved families.

It is a small thing, but perhaps it will give them some measure of comfort.

And there it was, the direct connection between Father Donnelly, the Hartley’s, and the photograph now sitting in Sarah’s museum archive.

The priest had recommended Whitmore specifically because he knew how to handle memorial photography with sensitivity and dignity.

Sarah left St.

Annes with copies of Father Donny’s journal entries, but she knew she needed more.

Historical records could tell her about Rose’s death, but they couldn’t fully capture who she had been in life.

For that, she needed to find living memory, descendants, relatives, anyone who might have family stories passed down through generations.

Back at the museum, she began the painstaking work of genealological research.

Using census records, city directories, and online databases, she traced the Hartley family forward from 1901.

William and Margaret Hartley had remained in Lawrence after Rose’s death.

The 1910 census showed them still living on Jackson Street, but now with two more children, a son, Thomas, born in 1903, and another daughter, Alice, born in 1905.

They seem to have survived their grief and rebuilt their lives.

Sarah followed the paper trail.

Thomas Hartley married in 1925, had four children, worked as a mill foreman.

Alice married in 1928, moved to nearby Methwin, had three children.

The family tree branched and spread.

Then through an online genealogy forum, Sarah found a post from 7 months earlier.

Looking for information about the Hartley family of Lawrence, MA, circa 1900.

My great great-grandmother was Margaret Hartley.

Sarah’s pulse quickened.

She sent a private message to the poster, a woman named Jennifer Morrison, who lived in Portland, Maine.

2 days later, Jennifer called her.

“I’m so glad you reached out,” Jennifer said excitedly.

“I’ve been trying to piece together my family history, and there’s always been this mystery about my great great-grandparents.

My grandmother mentioned that they had lost a child before she was born, but she never knew the details.

” “Your great great grandparents were William and Margaret Hartley,” Sarah confirmed.

They lost their daughter Rose to dtheria in 1901.

She was 6 years old.

There was a long silence on the phone.

Then Jennifer spoke, her voice thick with emotion.

Rose.

I never knew her name.

Sarah arranged to meet Jennifer the following week.

The woman drove down from Maine with a shoe box full of family photographs, documents, and heirlooms that had been passed down through the generations.

They spread everything on Sarah’s office desk.

Most of the photographs were from later years, Thomas and Alice as adults, their children, family gatherings in the 1920s and 30s.

But at the bottom of the box, wrapped carefully in tissue paper, was something that made Sarah’s breath catch.

It was a small silver brooch, oval-shaped with the initials M and H engraved in Victorian script.

That belonged to my great great grandmother, Margaret, Jennifer said.

My grandmother Alice wore it for years, and she gave it to me before she died.

She said it was precious to her mother, but she never explained why.

Sarah pulled up the memorial photograph on her computer.

There, on Margaret Hartley’s dress, was the same brooch worn on the day they said goodbye to Rose.

Jennifer stared at the photograph on Sarah’s screen, tears streaming down her face.

I had no idea this existed,” she whispered.

“My family never talked about Rose.

I think the grief was too deep.

They just buried it along with her.

” Sarah had seen this before in her research.

Victorian and early 20th century families often dealt with child mortality by not speaking of it, especially if the loss was particularly traumatic.

The pain was too raw to be shared, even across generations.

“Your grandmother, Alice, was born 4 years after Rose died,” Sarah said gently.

Margaret and William had already lost one child.

I can’t imagine how terrified they must have been with each subsequent pregnancy, each childhood illness.

Jennifer nodded, wiping her eyes.

My grandmother used to tell me that her mother was very protective, overly protective, she said.

She wouldn’t let the children play with certain neighborhood kids, insisted on boiling all the drinking water, was obsessive about cleanliness.

I thought it was just old-fashioned strictness.

Now I understand.

She was trying to keep them safe from what had killed Rose.

Sarah had found more information about the aftermath of the outbreak.

The contaminated well on Jackson Street was finally sealed in late 1901 after the Lawrence Health Department conducted a formal investigation.

The city had installed new water lines to the tenement district by 1903.

The changes came too late for Rose and the other children who had died, but they likely saved countless other lives.

Jennifer explored the shoe box again, pulling out a small leatherbound book.

This was in my great grandmother Alice’s things.

I’ve never been able to read it.

The handwriting is too faded and old-fashioned.

Sarah opened the book carefully.

It was a diary.

The entries written in elegant Victorian script.

The first page was dated January 1st, 1920.

She read aloud, “This diary belongs to Alice Hartley, given to me by my mother on my 15th birthday.

Mother told me today about my sister, Rose, who died before I was born.

She said Rose would have been 25 years old this year and might have had children of my own age by now.

” Mother cried as she told me the story, the first time I’ve ever seen her cry.

She said she wanted me to know about Rose so that she would not be forgotten.

The diary went on for several pages recording what Margaret had told her daughter about Rose, that she had been gentle and kind, that she loved to sing, that she had tried to help care for the younger children in the building even though she was just six.

That on the day she became sick, she had been playing with her godmother, Catherine, who had died just 3 days earlier.

She wanted Rose to be remembered, Jennifer said softly.

That’s why she kept the photograph, the brooch, the stories.

She couldn’t bear the thought of Rose disappearing from history entirely.

Sarah looked at the photograph again, Williams clenched jaw, Margaret’s devastated eyes, Rose’s small still form between them.

It wasn’t just a memorial.

It was an act of defiance against forgetting, against the idea that a child’s life could simply end and leave no trace.

I’d like to include this photograph in our exhibition on Victorian Boston, Sarah said carefully, but only with your permission.

I want to tell Rose’s story properly, not as a morbid curiosity, but as a piece of social history, a reminder of what life was like for working families, of what they endured, of how much has changed.

Jennifer didn’t hesitate.

Yes, absolutely.

Yes.

Rose deserves to be remembered.

6 months after Sarah first examined the photograph, the Boston Heritage Museum opened its new exhibition, Lives Remembered: Victorian Memorial Photography and the Stories They Tell.

The centerpiece was the Hartley family portrait displayed with full historical context.

Sarah had worked with the museum’s design team to create a respectful educational presentation.

The photograph was mounted on a wall painted soft gray with carefully worded text panels explaining post-mortem photography as a historical practice, not sensationalized, but acknowledged as a legitimate form of grief and remembrance.

Rose’s story was told through archival materials displayed alongside the photograph.

a copy of her death certificate, Father Donnie’s journal entries, newspaper clippings about the Dtheria outbreak, a map showing the tenement district, and photographs of Lawrence’s Mills.

The brooch loaned by Jennifer was displayed in a small case.

But Sarah’s favorite part was a panel titled Rose Katherine Hartley, 1894 1901.

It read, “Rose was 6 years old when she died of dtheria on March 31st, 1901 during an outbreak that killed more than 30 children in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

She lived on Jackson Street with her parents, William, a loom operator, and Margaret.

She loved to sing in church.

She helped care for younger children in her tenement building.

She was learning to read.

Rose died from a disease that spread through her neighborhood because of contaminated water and overcrowded housing, conditions created by the industrial economy that employed her father.

Her death was one of thousands of preventable child deaths in American miltowns during this era.

Her parents commissioned this memorial photograph so she would not be forgotten.

More than a century later, we honor their wish.

The exhibition opened on a Saturday morning in May.

Sarah stood near the Heartley photograph, watching visitors read the panels and study Rose’s face.

Some people moved on quickly, uncomfortable with the subject matter, but many lingered, reading every word, their expressions thoughtful and moved.

Jennifer came to the opening with her teenage daughter, Margaret’s great great great granddaughter, and Rose’s great great grand niece.

The girl stood in front of the photograph for a long time.

Studying the face of the ant she never knew existed.

She looks like you, Mom, the girl said quietly.

Around the eyes, Jennifer squeezed her daughter’s hand.

I see it, too.

An elderly man approached Sarah near the end of the day.

My grandfather worked in the Lawrence Mills, he told her.

He came over from Poland in 1898.

He always said the owners cared more about the looms than the workers.

Seeing this, he gestured at the photograph.

It makes it real.

These weren’t just statistics.

They were children.

That evening, after the museum closed, Sarah stood alone in the gallery.

She thought about the journey the photograph had taken from James Whitmore’s studio in 1901 through unknown hands and decades of storage into a donated collection and finally to this wall where thousands of people would see it and learn Rose’s name.

She thought about William and Margaret Hartley, who had scraped together money in the midst of their grief to ensure their daughter would be remembered.

She thought about Father Donnelly, who had held crying parents and recorded their stories.

She thought about Margaret telling her daughter Alice about the sister she’d never met, refusing to let Rose be erased.

The photograph ah had done its work.

Rose was remembered.

Her short life mattered.

And the conditions that killed her, the preventable diseases, the industrial exploitation, the public health failures were documented not as abstractions, but as lived experience.

Sarah touched her fingers to the glass over the photograph, a gesture of respect and connection across time.

“Your mother wanted you remembered, Rose,” she whispered.

And you are.

News

Historians Restored This 1903 Portrait — Then Noticed Something Hidden in the Man’s Glove Emma Brooks adjusted her computer screen, squinting at the sepia toned photograph that had arrived at the Pennsylvania Historical Society three days earlier. The image showed a family of five standing in a modest garden, their faces frozen in the stern expressions common to early 20th century portraits. The father stood at the center, one hand resting on his wife’s shoulder, the other hanging stiffly at his side. Three children flanked them, the youngest barely tall enough to reach her mother’s waist. The photograph had been donated by Katherine Miller, an elderly woman from Pittsburgh who claimed it showed her great-grandparents. Emma had seen hundreds of similar images during her 15 years as a photographic historian. But something about this one nagged at her. Perhaps it was the quality of the original print, remarkably well preserved despite its age, or the intensity in the father’s eyes that seemed to pierce through more than a century of distance.

Historians Restored This 1903 Portrait — Then Noticed Something Hidden in the Man’s Glove Emma Brooks adjusted her computer screen,…

Why Did Historians Become Pale When Enlarging the Face of the Younger Girl in This 1891 Image? The Haunting Revelation of the 1891 Portrait In the dim light of the archive room, Dr. Eleanor Hayes meticulously examined the faded photograph, its edges curling with age. The image depicted a young girl, her face innocent yet enigmatic, captured in a moment that transcended time. But as Eleanor enlarged the photograph, a chill ran down her spine. The girl’s eyes, once merely a reflection of childhood, now seemed to harbor secrets that could unravel history itself. Eleanor had dedicated her life to understanding the past, but this image was different. It was as if the girl was staring into her soul, demanding to be heard. The historians had warned her about this particular photograph, claiming it was cursed, a relic that had brought misfortune to those who dared to delve too deep. But Eleanor, driven by an insatiable curiosity, pressed on. As she zoomed in, the girl’s face transformed. The smile that once appeared sweet now twisted into something sinister.

Why Did Historians Become Pale When Enlarging the Face of the Younger Girl in This 1891 Image? The Haunting Revelation…

🚨 Greg Biffle’s last flight revealed in 60 seconds as a countdown compresses terror into heartbeats, timelines snap shut, and every routine check feels fateful while the sky turns witness to courage, pressure, and a moment that refuses to stay silent ✈️⏱️ the narrator slices time with a razor voice, hinting that when seconds decide legends, the truth doesn’t shout—it clicks, pops, and dares you to keep watching 👇

The Final Descent In the heart of the night, the engines roared like a beast awakened from slumber, echoing through…

🤖 Salvaging & restoring the giant Robot Batman abandoned at the bottom of the ocean turns into a gothic rescue opera as divers descend into ink-black pressure, find a rusted vigilante staring back, and spark a clash between nostalgia and nightmare when cables tighten and the legend refuses to stay buried 🦇🌊 the narrator growls that this isn’t scrap recovery, it’s an exhumation of myth, where every bolt screams history, every bubble carries regret, and the sea seems angry about losing its darkest trophy 👇

Echoes from the Abyss: The Resurrection of the Forgotten Titan In the depths of the ocean, where light dares not…

End of content

No more pages to load