This 1901 portrait of two sisters looks harmless until you see what one is holding.

Dr.Michael Hayes had seen the thousands of photographs in his 20-year career as a Civil War era historian, but something about this particular portrait stopped him cold.

It was a humid Tuesday afternoon in August 2018 when he first encountered the image at a Charleston estate sale.

The photograph showed two young women in their 20s seated side by side in an elegant parlor, their Victorian dresses immaculate, their expressions serene.

The handwritten inscription on the back read simply, “Catherine and Ellaner, March 1901.

” Michael almost passed it by.

Another formal portrait from the turn of the century, destined for some collector’s drawer.

But there was something in the older sister’s eyes.

Catherine, he assumed, that held a quality he couldn’t quite name.

Not fear, exactly.

Something deeper, something that made his historian’s instinct pulse with recognition.

He purchased the photograph for $12 along with a box of miscellaneous documents and carried it back to his office at the College of Charleston.

Under the afternoon light streaming through his window, he examined it more carefully.

The photography was professional, likely taken at one of Charleston’s better studios.

The women wore their hair in the Gibson girl style, popular at the time.

Their posture was rigid, as was customary for long exposure times.

The studio backdrop showed a painted scene of a Charleston garden, complete with aelas and rot iron gates.

The furniture was expensive, a velvet sati with carved mahogany legs.

These were not poor women.

They came from at least moderate means or had married into it.

Their dresses, though formal and high- necked in the fashion of the era, showed quality tailoring.

Catherine wore dark burgundy wool with jet buttons.

Ellaner wore lighter gray silk with delicate lace at the collar and cuffs.

Michael set up his digital scanner, adjusting the resolution to its highest setting.

He’d learned over the years that modern technology could reveal details invisible to the Victorian eye.

Tiny inscriptions on jewelry, hidden tears and clothing, even the titles of books barely visible on shelves in the background.

The scanner could capture what the human eye missed, what even the photographer might not have noticed.

As the machine hummed to life, he wondered idly about these sisters, who they were, what their lives had been like in a Charleston, still recovering from the Civil War’s devastation, still defining itself in the new century.

He had no idea he was about to uncover a secret that had remained hidden for 117 years.

A secret that would consume the next 6 months of his life and finally bring justice to two women who had been silenced over a century ago.

The highresolution scan loaded on Michael’s computer screen, and he began his usual methodical examination.

He zoomed in on the women’s faces first, noting the subtle differences in their features.

Catherine, the older sister on the left, had sharper cheekbones and darker eyes that seemed to stare directly through the camera lens.

There was an intensity there, a guardedness.

Elellanar’s face was softer, rounder, with a gentle smile that seemed genuine despite the formal setting.

But now, looking closer, Michael could see tension around her eyes, a tightness in her jaw.

He moved down to examine their clothing.

The intricate lace collars, the mother of pearl buttons, the delicate embroidery on their sleeves.

Then he reached Catherine’s hands, folded primly in her lap, partially obscured by the cascading fabric of her dark wool dress.

The fabric fell in heavy folds, creating deep shadows in the photograph.

Michael froze.

His breath caught as he leaned closer to the monitor.

Certain his eyes were deceiving him.

He zoomed in further, the pixels expanding until the image became grainy, then adjusted the contrast and brightness, his heart began to pound in his chest, each beat seeming to echo in the quiet office.

There, barely visible in the shadows of the dress folds, partially concealed by Catherine’s right hand, the unmistakable outline of a small pistol.

The grip was ornate, likely pearl or ivory, catching a tiny fragment of light from the studio window.

The barrel was short, compact, a daringer, if he had to guess.

The kind of weapon a woman might hide in a purse or pocket for protection.

“Jesus Christ,” Michael whispered to the empty office.

He sat back in his chair, his mind racing through possibilities.

Women occasionally carried small firearms in that era for protection, especially in cities.

It wasn’t unheard of.

But to bring one to a professional photography session, to hold it concealed during a formal portrait that required sitting absolutely still for several seconds of exposure, that wasn’t just unusual.

That was deliberate.

That was calculated.

That was desperate.

Michael zoomed out and looked at the full portrait again.

Now he noticed other details he’d missed before.

The way Catherine’s left hand gripped the armrest of the seti, knuckles white with tension.

The way Ellanar sat slightly closer to her sister than would have been typical for such formal portraits.

The way both women’s eyes, despite the requisite stillness of Victorian photography, held something that made his stomach tighten.

Michael looked again at Catherine’s eyes in the photograph, and suddenly that unnamed quality he’d noticed earlier had a name.

It wasn’t just intensity or guardedness.

It was terror.

Michael spent the rest of that evening staring at the photograph, unable to shake the growing sense of dread settling in his chest.

He printed multiple versions, standard enhanced, with the weapon area circled in red.

He’d worked with historical photographs depicting violence before, Civil War casualties, lynching victims, crime scenes from Charleston’s darker past.

But this was different.

This was violence anticipated, not yet committed.

This was a woman preparing for something terrible, something she knew was coming.

He barely slept that night.

The image of Catherine’s terrified eyes haunted him.

When he finally dozed off around 3:00 in the morning, he dreamed of a woman drowning, her hand reaching up from dark water, still clutching a small pistol that gleamed in the moonlight.

The next morning, he arrived at the South Carolina Historical Society before it opened, clutching a folder containing enlarged prints of the photograph.

Margaret Wilson, the head archist, and his longtime colleague, looked up from her desk as he entered.

She was organizing a new shipment of documents from a private collection, her reading glasses perched on her nose.

You look like you’ve seen a ghost, she said, removing her glasses and setting them aside.

I might have.

Michael spread the photographs across her desk, his hands trembling slightly as he pointed to the enhanced image showing the pistol.

1901, two sisters, Charleston.

One of them is holding a concealed weapon during a professional portrait session.

Margaret leaned forward, her expression shifting from curiosity to concern as she examined the images.

She picked up the enhanced version, holding it close to her face, then setting it down and looking at the original.

Good lord, that’s a Remington double daringer if I’ve ever seen one.

Popular among women at the time for personal protection, but Michael, I know, why would she bring it to a photography studio? Unless she was afraid to be without it, Margaret finished quietly, her voice dropping.

Unless she believed she might need it at any moment, even in a public place, even surrounded by witnesses, she looked up at him, and he could see his own disturbed thoughts reflected in her eyes.

Do we have names? Catherine and Ellaner.

No surnames yet.

The photo came from the Whitmore estate sale on Trad Street last Tuesday.

I bought it with a box of miscellaneous papers, but there was nothing else about these women in the collection.

Margaret was already moving toward the archives, her fingers trailing along rows of leatherbound record books.

If they were photographed professionally in Charleston in 1901, there should be records.

Studio photographers kept detailed logs, names, addresses, payment receipts.

They had to for tax purposes and for reprints.

They spent the next four hours searching through dusty ledgers from Charleston’s photography studios.

The city had boasted at least a dozen professional photographers at the turn of the century, each competing for the business of Charleston’s recovering merchant class.

Michael and Margaret worked methodically through each studio’s records, cross- referencing dates and descriptions.

Finally, in the records of Townsend and Grey photographic artists, Margaret found it, her finger stopped on a line of elegant cursive writing, and she drew in a sharp breath.

here.

March 14th, 1901.

Katherine and Ellaner Brennan.

Two sisters, formal portrait, one sitting.

Address listed as 67 Church Street.

Payment $3.

Paid by Mr.

Thomas Brennan.

E.

Michael wrote down the information, his hand trembling slightly.

The husband paid for it.

He commissioned the portrait, which means he wanted it, Margaret said thoughtfully.

This wasn’t something Catherine arranged in secret.

He made them pose for this photograph.

They moved to the census records, pulling the heavy volumes for Charleston County in 1900.

The handwritten entries were faded but legible.

Katherine Brennan, aged 26 in 1901, was listed as married to Thomas Brennan, a shipping merchant 15 years her senior.

They lived at 67 Church Street, a respectable address in Charleston’s merchant district in a house valued at $1,200.

Thomas Brennan’s occupation was listed as cotton factor and shipping agent.

His assets were listed as substantial.

Elellaner, 23, was listed as residing at the same address, unmarried, occupation, none.

Her relationship to the head of household, sister-in-law.

Michael Cross referenced property records and found that the church street house had been purchased by Thomas Brennan in 1898, 3 years before the photograph was taken.

Tax records showed he’d made his fortune in cotton shipping, capitalizing on Charleston’s efforts to rebuild its trade economy after the devastation of the Civil War.

He’d arrived in Charleston in 1895 with letters of credit from banks in Virginia, established his business quickly, and married Katherine Fletcher in 1899.

“Look at this,” Margaret said, pointing to a Charleston News and Courier Society column from April 1899.

Mr.

Thomas Brennan and Miss Katherine Fletcher were united in marriage at St.

Michael’s Episcopal Church.

The bride’s sister, Miss Ellanar Fletcher, served as maid of honor.

The bride is the daughter of the late Samuel Fletcher, merchant, and inherits a modest estate.

Fletcher was their maiden name, Michael noted, writing it down carefully.

So, Ellaner moved in with her sister after the marriage.

That was common enough if she was unmarried and had no parents living.

But Margaret was already pulling another record, and the expression on her face made Michael’s stomach drop.

Michael, look at this police report from February 1901.

One month before the photograph was taken, Michael leaned over her shoulder, reading the faded handwritten report.

A neighbor on Church Street, Mrs.

Adelaide Porter had reported sounds of a violent domestic disturbance at number 67 around 10:00 in the evening.

Shouting the sound of breaking glass, a woman’s scream, officers were dispatched.

Thomas Brennan answered the door, explained calmly that his wife had suffered a fall down the stairs and had knocked over a vase.

The officers noted that Mrs.

Brennan appeared shaken, but confirmed her husband’s account.

Her sister, Miss Fletcher, was also present, and nodded her agreement.

No visible injuries were observed.

No arrest was made.

Case closed.

She didn’t fall, Michael said quietly, his jaw clenched.

Of course, she didn’t fall, Margaret replied, her voice tight with anger that transcended a century.

And a month later, she’s posing for a photograph with a pistol hidden in her dress.

She knew.

She knew what he was capable of, and she was preparing herself.

Michael returned to his office that evening with copies of everything they’d found, spreading the documents across his desk like pieces of a puzzle that refused to fit together.

The autumn sun was setting over Charleston, casting long shadows through his window.

He made coffee and settled in for what he knew would be a long night, he searched through Charleston’s death records for 1901, half dreading what he might find.

The leatherbound register was organized chronologically, he ran his finger down the entries for April, May, June.

Katherine Brennan’s name appeared in the register for June 17th, 1901.

Cause of death, accidental drowning.

Location, Charleston Harbor, East Bay Street docks.

Age, 26 years.

Body recovered by harbor patrol, identified by husband, Thomas Brennan.

burial, Magnolia Cemetery.

Attending physician, Dr.

James Morton, three months after the photograph, just three months.

Michael’s hands shook as he read the brief entry.

There was no autopsy report attached, no investigation record.

Nothing but that single line in the death register.

The notation was prefuncter, bureaucratic, suggesting nothing unusual had warranted further inquiry.

He searched for Ellaner’s name in the subsequent months, the years following.

Nothing.

She simply vanished from all records after March 1901.

No death certificate, no marriage license, no census entry in 1910, no listing in city directories.

It was as if Elellanar Fletcher had ceased to exist the moment that photograph was taken.

The next morning, exhausted but driven, Michael drove to the Charleston County Courthouse, where older records were stored in climate controlled vaults in the basement.

The clerk on duty was a young woman named Sarah, a graduate student in library science who understood the urgency researchers sometimes felt.

We had a fire in 1902, Sarah explained as she pulled the relevant boxes from the shelves, her voice echoing in the concrete vault.

Started in the records office, spread quickly.

A lot of records from 1900 to 1902 were damaged or destroyed completely.

It’s incredibly frustrating for researchers like you.

Michael opened the box labeled June 1901, Deaths and Inquests, with trembling fingers.

Most of the documents inside were smoke damaged, the edges brown and brittle, some pages stuck together with age and water damage from the fire hoses.

He found Catherine’s death report, but entire sections had been burned away, leaving only fragments of words and sentences.

What remained was barely legible.

Body recovered from harbor at dawn, identified by husband.

No signs of investigation deemed accidental.

Dr.

Morton certifies the words between were ash.

The physician’s full report, if there had been one, was gone.

Any witness statements, any details about the condition of the body, all of it consumed by flames.

There’s something else, Sarah said, pulling out a separate folder marked probate and estate matters.

July 1901.

This was filed separately, so it survived the fire.

Michael opened it with a growing sense of dread.

Inside was a petition to the court dated July 3rd, 1901.

Thomas Brennan had petitioned to be declared the sole heir to his wife’s estate and to have Elellanar Fletcher declared legally missing and presumed dead.

The petition claimed that Elellanar had disappeared in a state of emotional distress following her sister’s accidental death and that despite extensive searches, no trace of her had been found.

Thomas Brennan therefore requested the court’s permission to dispose of her personal effects and to assume control of any assets.

The petition was granted on July 15th, 1901.

The judge’s signature was barely a scroll at the bottom of the page.

“He got everything,” Michael said quietly, staring at the document.

“The house, whatever money Catherine had inherited from her father, Ellaner’s belongings, everything.

and Elellanar just disappeared into thin air.

Sarah looked over his shoulder at the petition, her young face troubled.

“You think he killed them both, don’t you?” Michael looked up at her, and in that moment, his historian’s objectivity crumbled.

“I don’t think, Sarah, I know Catherine knew it, too.

That’s why she brought a gun to a photography studio.

” Michael’s breakthrough came from an unexpected source 3 weeks later.

While searching through old Charleston newspapers on microfilm, his eyes burning from hours of staring at the scrolling pages, he found a small advertisement in the July 1901 classified section of the Charleston News and Courier.

It was buried among notices for missing livestock and requests for household staff.

Mrs.

Abigail Porter seeks information regarding her dear friend, Miss Ellanar Fletcher, last seen in March of this year.

Miss Fletcher is 23 years of age, fair-haired of Slenderbuild.

Anyone with knowledge of her whereabouts, please contact Mrs.

A.

Porter at 89 King Street.

Utmost discretion assured, reward offered.

The advertisement had run for three consecutive weeks, then stopped.

Michael’s hands shook as he printed the page.

With Margaret’s help and access to genealological databases, Michael traced Mrs.

Abigail Porter’s descendants through marriage records, birth certificates, and census data.

It took two weeks of painstaking research, following branches of the family tree through four generations.

Finally, they found her.

Abigail Porter’s great great granddaughter, Linda Chen, still lived in Charleston’s historic district and agreed to meet with Michael at a coffee shop on Broad Street.

Linda arrived on a cool October afternoon carrying a small wooden box that looked as old as the city itself.

She was a retired school teacher in her 70s with kind eyes behind wire- rimmed glasses and gray hair pulled back in a neat bun.

She set the box on the table between them with a gentleness that suggested it contained something precious.

“My great great grandmother kept everything,” Linda explained, her fingers resting protectively on the box’s lid.

letters, newspaper clippings, photographs, pressed flowers, theater programs.

She was what we’d now call a hoarder, but a very organized one.

She was obsessed with what happened to Ellanar Fletcher.

It haunted her for the rest of her life.

She died in 1943 at the age of 87.

And according to my grandmother, Ellaner’s name was one of the last words she spoke.

Inside the box, carefully preserved in tissue paper and organized chronologically, Michael found letters written in elegant cursive, newspaper articles about Catherine’s death, several photographs of young women at garden parties and church socials, and pressed flowers tied with faded ribbons.

But what stopped his breath completely was a letter dated March 10th, 1901, 4 days before the portrait was taken.

The paper was yellowed with age, but the ink was still dark, the handwriting flowing and controlled despite the trembling urgency evident in certain words where the pen had pressed harder.

Dear Abigail, it began in Catherine’s handwriting.

I fear this may be the last letter I write to you, and I pray I’m wrong, but I must tell someone the truth in case the worst comes to pass.

Thomas’s violence has escalated beyond what Eleanor and I can endure any longer.

What began as harsh words and small cruelties has become something far more dangerous.

He has threatened our lives directly, telling me that I am his property and that Eleanor is a burden he will not tolerate much longer.

We have made arrangements to leave Charleston, but we must wait until his business takes him to Savannah next month.

He has a cotton shipment that will keep him away for at least 3 days.

Eleanor and I will pose for a portrait this week at his insistence as he wants a proper image of his wife and sister-in-law for his office.

He wants proof of his respectable family.

I will bring protection with me.

I’ve purchased a small pistol and have learned to use it.

If something happens to us before we can escape, please know that we tried our best to survive.

Please remember us kindly, your devoted friend, Catherine.

Michael looked up at Linda, his throat tight with emotion.

She knew.

She knew he would kill her.

Michael stood at the edge of Charleston Harbor on a gray October morning, looking out at the water that had claimed Katherine Brennan 117 years ago.

The harbor was busier now, tourist boats departing for Fort Sumpter, shipping containers stacked like children’s blocks at the port.

The occasional yacht cutting through the choppy water, but the water itself was unchanged, dark, cold, unforgiving.

The same water that had closed over Catherine’s head, filling her lungs, ending her desperate attempt to escape.

He’d spent the past week diving deeper into Thomas Brennan’s background, and what he’d found painted a portrait of a man who’d built his entire life on carefully constructed lies.

Brennan had arrived in Charleston in 1895, claiming to be from a wealthy Virginia shipping family with connections to the tobacco trade.

But Michael had traced the records backward, contacting historians in Richmond, Norfick, and Petersburg.

There was no such family.

No Brennan’s in the shipping business, no tobacco fortune.

Thomas Brennan had invented himself completely, used borrowed money and forged letters of credit to establish his Charleston business, and married Katherine Fletcher, specifically for her modest but real inheritance from her merchant father.

When that money began to run out in early 1901, when creditors began asking difficult questions, he’d needed her dead, and he’d needed it to look accidental.

Margaret had helped Michael obtain access to the maritime records from June 1901, stored in the files of the harbor master’s office, ship’s logs, harbor patrol reports, witness statements from dock workers and sailors.

The official story was that Katherine had been walking alone along the harbor at dusk, slipped on the wet dock planking, and fallen into the water.

Her body was recovered the next morning by the harbor patrol caught against the pilings near Ager’s Wararf.

She was identified by her husband, who’d reported her missing when she failed to return home from an evening walk.

But the ship’s log from the Mary Catherine, a merchant vessel docked that evening for repairs, told a different story buried in routine entries.

The night watchman, a sailor named James Mitchell, had noted hearing a woman scream around 9:00, followed by a splash.

By the time he’d reached the rail and looked over, he’d seen only dark water and in the distance, a man in a dark coat walking away from the dock toward the street.

He’d reported it to the harbor master the next morning, but no investigation had followed.

The report was filed with dozens of others.

drunken sailors falling overboard, cargo accidents, routine incidents in a busy working harbor.

It took another week of genealological research, but Michael finally found James Mitchell’s descendants, a grandson named Robert, who still lived in Charleston’s historic district in a small house that had been in his family for five generations.

Robert was in his 90s now, frail but sharp-minded, his dark skin weathered by age, his hands gnarled with arthritis.

Michael visited him on a Sunday afternoon.

The old man sat in a rocking chair on his front porch, a quilt across his lap despite the mild weather.

My grandfather talked about that night until the day he died,” Robert said, his voice quiet but steady.

“He was 23 years old, working as night watch on the Mary Catherine.

He saw Thomas Brennan push that woman into the harbor.

He saw him hold her under the water with a long boat hook until she stopped struggling.

Watched him look around to make sure no one had seen, then walk away like nothing had happened.

” “Why didn’t he testify?” Michael asked, though he already knew the answer.

Robert’s laugh was bitter, edged with a century of accumulated anger.

Black man accusing a white merchant in 1901 Charleston.

My grandfather would have been lynched before he made it to the courthouse.

He told the harbor master what he saw, and the harbor master told him to forget about it if he wanted to keep breathing.

So, he kept his mouth shut and carried the guilt until he died in 1954.

The deeper Michael dug into the mystery of Ellaner’s disappearance, the more convinced he became that she had witnessed her sister’s murder.

The timeline suggested it was possible Catherine had been killed on the evening of June 17th.

Elellanar had last been seen the same day, according to the missing person notice Abigail Porter had placed in the newspaper.

The question that haunted Michael’s dreams was, “What happened to her afterward?” He found a partial answer in the records of St.

Phillip’s Episcopal Church, one of Charleston’s oldest congregations.

Father William Graves, the recctor in 1901, had kept detailed personal journals that were now preserved in the church archives, protected by the current recctor, who understood their historical value.

Michael spent an afternoon in the church library, a small room that smelled of old paper and furniture polish, reading through entries from June 1901.

Finally, he found what he was looking for.

The handwriting was elegant.

The ink faded to brown.

June 18th, 1901.

A young woman came to the rectory this evening in great distress, arriving just after Compline prayers.

She would not give her name, but said her sister had been murdered by her sister’s husband the previous evening.

She claimed to have witnessed the crime at the harbor, but was too terrified to go to the police, saying they would not believe her.

She begged for sanctuary.

I could see she was genuinely terrified.

Her hands shook.

Her eyes were wild.

I provided her shelter for the night in the small room we keep for travelers in need.

gave her bread and soup and promised to help her reach family in Atlanta.

In the morning, when I went to wake her, she was gone.

I found blood on the bed sheets where she had slept.

Not much, but enough to concern me.

There was also a torn piece of her dress caught on the window latch.

She must have climbed out during the night and fled.

I do not know why.

I reported the incident to the police, but they showed little interest.

They said the woman was likely disturbed in her mind, and that Mrs.

Brennan’s death had been ruled accidental.

I pray for that poor, frightened girl, whoever she was.

Michael showed the entry to Margaret back at the historical society.

She was injured, the blood on the sheets, probably when Thomas realized she’d witnessed the murder or when he came after her that night.

Margaret added darkly.

She was staying in the same house with him.

If she saw what happened at the harbor and ran home, he would have known he would have come for her.

They expanded their search to train records, stage coach lines, ferry services, anything that might show Ellaner leaving Charleston.

A woman traveling alone in 1901 would have been noticed, would have had to purchase tickets, would have appeared in passenger logs.

But they found nothing.

No Ellaner Fletcher, no Ellen Brennan, no unidentified young woman matching her description.

Then Michael discovered something in the property records that made his blood run cold.

In July 1901, just weeks after Catherine’s death and Elellaner’s disappearance, Thomas Brennan had filed paperwork with the city to have extensive renovations done to the basement of 67 Church Street.

The work permit described structural improvements and storage expansion.

The work was completed quickly, unusually quickly, in less than two weeks, and the permits were signed off without the customary final inspection.

A $50 payment to the building inspector’s office was noted in the records.

A bribe.

He buried her, Michael said, the realization hitting him like a physical blow.

His voice shook.

He buried Ellaner under his own house.

Margaret closed her eyes, her hand pressed to her mouth.

Dear God Mul, the current owners of 67 Church Street were David and Jennifer Martinez, a young couple in their 30s who’d purchased the property two years earlier and had been slowly renovating the historic home.

When Michael contacted them in November 2018 and carefully explained his research, the photograph, the hidden weapon, the evidence of murder, the suspicious basement renovations, they were horrified, but agreed immediately to allow a ground penetrating radar survey.

“If there’s someone buried under our house,” Jennifer said, her face pale.

We need to know.

Those women deserve justice, even if it’s a century too late.

The Charleston Police Department opened an official investigation in early December.

Despite the age of the alleged crimes, the discovery of potential human remains mandated a full response.

The case was assigned to Detective Sarah Martinez, no relation to the homeowners, a specialist in cold cases, who’d worked several high-profile historical investigations.

The ground penetrating radar survey took place on a cold December morning.

Michael watched, his heart pounding as the technician moved the equipment methodically across the brick floor of the basement.

The old house groaned and settled around them.

David and Jennifer Martinez stood in the doorway, holding hands, their faces tense.

20 minutes into the survey, the technician stopped abruptly.

“I’ve got something,” she said, her voice carefully neutral.

“Northeast corner, anomaly in the soil beneath the foundation, approximately 6 ft long, 2 ft wide, depth of about 4 feet.

The density and composition are consistent with disturbed earth and organic material.

The size and shape were consistent with human remains.

Detective Martinez made the call.

Within hours, a full forensic team arrived.

The couple moved out temporarily, unable to bear staying in the house while the excavation proceeded.

Michael was allowed to observe from the perimeter as police tape went up and the careful, methodical work of archaeological excavation began.

They removed the brick floor one piece at a time, numbering and cataloging each one.

Beneath the bricks was a layer of concrete cracked with age.

Beneath that, dirt that had clearly been disturbed and refilled.

The forensic team worked with brushes and small tools, treating the site as they would any crime scene, photographing every layer.

Three days into the excavation, on a gray afternoon, with rain threatening, they found her.

The skeleton was remarkably well preserved, curled in a fetal position in a shallow grave.

She’d been wrapped in what remained of a wool blanket, now mostly rotted away, but still visible in fragments.

The forensic anthropologist, Dr.

Patricia Chen, confirmed immediately that the remains were consistent with a female in her early 20s, from the turn of the 20th century.

The bones showed no signs of disease, but were small, delicate, petite woman who probably hadn’t stood much over 5t tall.

But it was the skull that told the real story.

Dr.

Chen called Detective Martinez and Michael over, pointing with a gloved finger at the back of the cranium.

The bone showed a depressed fracture, the edges sharp and catastrophic.

Blunt force trauma, she said quietly.

Massive blow to the back of the head.

Would have been immediately fatal.

She never knew what hit her.

She tried to run, Michael said, his voice breaking.

She climbed out the window at the church and tried to get away, but she had to go back to the house for clothes, for money, for something she needed, and he was waiting for her.

With the remains, they found artifacts that confirmed her identity.

A tarnished locket on a broken chain.

When Dr.

Chen carefully opened it, inside were two small photographs miraculously preserved.

Two young women, faces barely visible, but recognizable from the 1901 portrait, Catherine and Ellaner.

They also found a small leather diary, water damaged but partially legible.

And most heartbreaking of all, folded in what remained of her dress pocket, a train ticket to Atlanta dated June 19th, 1901, the day after Catherine’s murder.

One-way passage.

Elellaner had scraped together enough money to escape.

She’d had her ticket.

She’d been planning to leave on the morning train.

She’d been so close.

The story broke in January 2019, and within hours, it had spread across the country.

The photograph of the two sisters, Catherine, with her terrified eyes and the pistol hidden in her dress, went viral.

News outlets ran features about the hidden weapon, the double murder that had gone unpunished for 117 years, and the cold case finally solved through a historian’s keen eye in modern forensic science.

The photograph that had sat forgotten in a drawer for over a century suddenly became a powerful symbol of domestic violence, of women’s voices, silenced by a patriarchal system, and of justice delayed but not denied.

Forensic analysis of Ellaner’s remains confirmed everything.

The skull fracture matched a blow from a heavy iron poker that investigators found during the excavation buried near the body and showing traces of blood and bone fragments still detectable after more than a century.

DNA analysis, while limited due to the age of the remains, was consistent with Elellanar being Catherine’s sister.

The dental records compared with a description from a Charleston dentist’s log that Margaret had unearthed were a perfect match.

Michael spent weeks following additional leads, piecing together Thomas Brennan’s life after the murders.

The merchants’s business had collapsed in 1905, his creditors finally catching up with him.

Records showed he’d left Charleston deeply in debt, fleeing to New Orleans, where he’d reinvented himself once again.

And there, Michael discovered something that made the horror complete.

Brennan had remarried twice more.

His second wife, Marie Devo, had died in 1908 of accidental poisoning.

His third wife, Sarah Lockwood, had drowned in Lake Poner Train in 1915 under suspicious circumstances.

Neither death had been properly investigated.

Thomas Brennan had spent his entire life murdering women and escaping justice, he’d finally died himself in 1923 at age 68.

Wealthy again through another profitable but fraudulent cotton speculation scheme respected in his New Orleans community, never having faced consequences for his crimes, he was buried in Metary Cemetery under a large marble monument that described him as a beloved husband and successful businessman.

The monument, Michael learned, had been quietly removed by cemetery officials in February 2019 after the full story became public.

The outcry from domestic violence advocates had been immediate and fierce.

Eleanor and Catherine were finally laid to rest together in Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston on a cold February morning in 2019.

The funeral was attended by hundreds.

Margaret and Michael, Linda Chen, and Robert Mitchell, representatives from domestic violence organizations, historians, journalists, and countless strangers who’d been moved by their story and wanted to pay respects to two women who’d fought so hard to survive.

The grave marker, paid for by crowdfunding that raised over $50,000 in less than a week, was made of white marble and read.

Katherine Fletcher Brennan, 1875 1901, and Ellaner Fletcher, 1888, 1901.

Sisters, murdered, but not forgotten.

silenced but now heard justice at last.

Oh.

Standing at the graveside as the minister said final prayers, Michael thought about that photograph, about Catherine’s terrified eyes that had first caught his attention, but the pistol hidden in the folds of her dress.

About two women desperate enough to bring a weapon to a photography studio because they knew their lives were in danger and understood that no one in their world would help them.

They’d known the police wouldn’t believe them.

They’d known society would side with the respectable merchant over his hysterical wife.

They’d known they were alone.

They tried so hard to survive.

Michael said quietly to Margaret as they walked back through the cemetery toward the car.

Spanish moss hung from the ancient oak trees and the February sun was weak and watery.

“They did survive,” Margaret replied, her voice firmed despite the tears on her cheeks.

Just not in the way they hoped.

Their story survived because Catherine was brave enough to hide that gun in plain sight, knowing it might not be enough to save them, but hoping it might be enough to tell the truth someday.

And it was.

It took 117 years, but it was.

Michael looked back at the fresh graves, at the flowers already piling up from people who’d never known these women, but were moved by their courage and their tragedy.

Someone had left a small replica of a daringer pistol, a symbol of Catherine’s desperate defiance.

Someone else had left a handwritten note that read simply, “We believe you.

We hear you.

Rest in peace.

” That night, Michael returned to his office one final time and looked at the photograph that had started everything.

The two sisters side by side, Catherine’s hand concealing the weapon that represented both her desperate hope and her terrible understanding that hope might not be enough.

In the end, that photograph had become exactly what Catherine had intended it to be, evidence.

Not in time to save them, but in time to tell their truth, to expose their murderer, to ensure that Thomas Brennan’s crimes would be remembered alongside his victim’s courage.

117 years later, the Fletcher sisters finally had their justice.

Their voices, silenced by violence and buried beneath a basement floor, had finally been heard.

Their story had been told.

Their murders had been solved.

And Thomas Brennan’s name would forever be associated not with respectability and success, but with the brutal murders of three wives and the cowardice of a man who’d spent his life destroying women who trusted him.

The photograph sat on Michael’s desk.

Catherine’s eyes staring out across more than a century.

And in those eyes, no longer did Michael see only terror.

Now he also saw defiance, courage, a refusal to be forgotten.

The sisters had won after

News

A 1904 Studio Photo Looks Harmless — But the Girl’s Hands Reveal a Frightening Detail A 1904 studio photo looks harmless, but the girl’s hands reveal a frightening detail. Professor David Richardson carefully arranged the collection of vintage photographs on his desk at the Boston Historical Archive. Each one a window into America’s past. The late afternoon sun filtered through the tall windows of his office, casting golden light across the sepia toned images that had arrived that morning from the Peton estate sale. Among dozens of typical family portraits from the early 1900s, one photograph immediately caught his attention. Not for any obvious reason, but for its seeming perfection, the 1904 studio portrait showed a young girl, perhaps 12 or 13 years old, seated in an ornate Victorian chair against a painted backdrop of pastoral scenery. She wore a pristine white dress with delicate lace trim, her dark hair arranged in the elaborate ringlets fashionable for children of wealthy families.

A 1904 Studio Photo Looks Harmless — But the Girl’s Hands Reveal a Frightening Detail A 1904 studio photo looks…

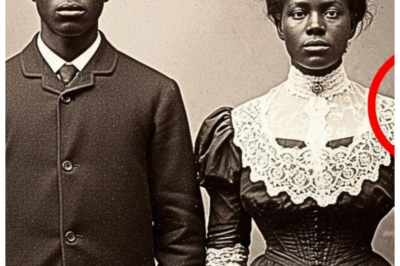

During the restoration, experts found a hidden detail in the slave girl’s clothing no one saw before During the restoration, experts found a hidden detail in the slave girl’s clothing no one saw before. Dr.Sarah Chen carefully positioned the dgerotype under the digital microscope, her breath shallow with concentration. The image before her was haunting. A young black girl, no more than 12, standing rigid beside a well-dressed white man in front of a columned mansion. New Orleans, 1858. The plate had arrived at the Smithsonian Conservation Lab 3 weeks ago, donated by an estate in Baton Rouge, and Sarah had been tasked with its restoration and authentication. The dgeray type was remarkably preserved. Its silver surface still reflecting light after 166 years. But something about the girl’s expression unsettled Sarah. While most enslaved people photographed in that era showed blank, emotionless faces, a defense mechanism against dehumanization, this girl’s eyes held something different. Not defiance exactly, but intention. Purpose.

During the restoration, experts found a hidden detail in the slave girl’s clothing no one saw before During the restoration,…

🔥 Tatiana Schlossberg at 35: Cause of Death Revealed—What Her Husband Endured, How Her Children Were Shielded, and Why Her Low-Key Lifestyle Hid a Fortune No One Talked About 💥 Said with sharp, tabloid bite, the lead suggests the truth cuts deeper than headlines, as insiders hint at hospital corridors, late-night decisions, and a family scrambling to protect legacy while mourning a loss that money, status, and history couldn’t stop 👇

The Untold Tragedy of Tatiana Schlossberg: A Life Shattered Tatiana Schlossberg, a name that once resonated with promise and legacy,…

💔 Dad Didn’t Understand Why His Daughter’s Grave Kept Growing—Until a Hidden Truth Shattered Him and Exposed a Silent Ritual That Left Him Collapsing in Tears at the Cemetery Gates 😭 The narrator whispers with cruel suspense, hinting that what began as confusion turned into a devastating revelation, as the father learns strangers had been secretly visiting, leaving objects, soil, and symbols that transformed grief into a haunting testament of love he never knew existed 👇

The Unraveling of a Legacy Tatiana Schlossberg was not just a name; she was a symbol of a storied lineage,…

💔 BREAKING: JFK’s Granddaughter Dies at 35—A Kennedy Tragedy Rewrites History Again as Tatiana Schlossberg’s Sudden Passing Sends Shockwaves Through a Family Long Haunted by Loss, Leaving America Whispering About Fate, Fragility, and the Price of a Legendary Name The narrator purrs with dramatic disbelief, hinting that this isn’t just another sad update but a chilling reminder that even America’s most storied dynasty cannot outrun sorrow, as insiders describe stunned relatives, hushed phone calls, and a grief so heavy it feels almost scripted by destiny itself 👇

The Unraveling of a Legacy Tatiana Schlossberg was not just a name; she was a symbol of a storied lineage,…

End of content

No more pages to load