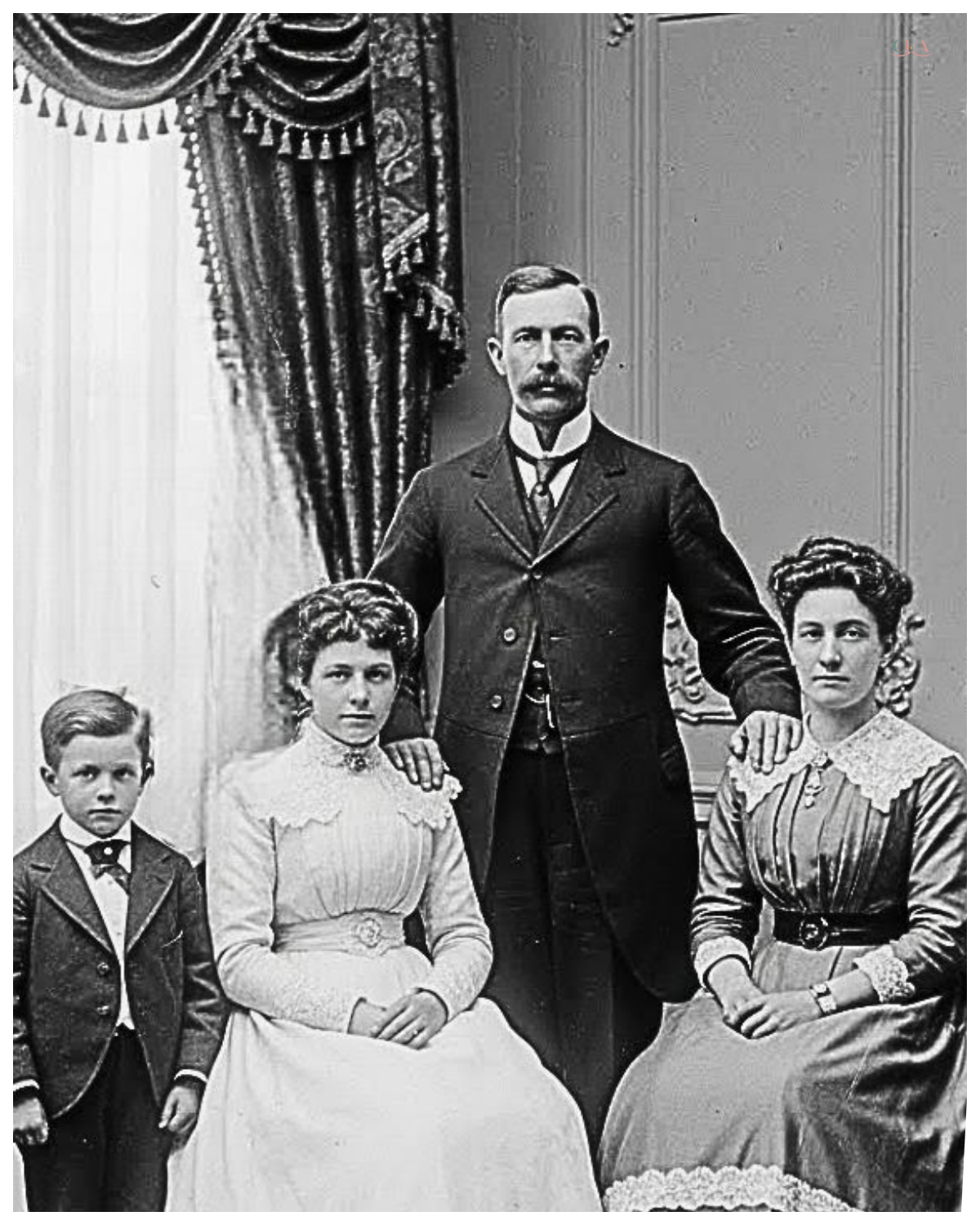

This 1900 portrait looked normal — until the background revealed who really took the picture

This 1900 portrait looked normal until the background revealed who really took the picture.

The afternoon light filtered through the tall windows of the Charleston Heritage Museum, casting long shadows across Dr.

Maya Robinson’s desk.

She adjusted her reading glasses and leaned closer to her computer screen, examining the highresolution scan of a photograph that had arrived that morning from an estate sale in the historic district.

The image itself seemed unremarkable at first glance.

A formal portrait from 1900 showing the Whitmore family, father, mother, and three children posed stiffly in their parlor.

The father stood with one hand on his wife’s shoulder.

The children arranged in descending height order.

Their clothing spoke of wealth, silk, lace, and perfectly tailored suits.

The backdrop showed the typical trappings of turn of the century prosperity, heavy curtains, ornate furniture, and a large decorative mirror mounted on the wall behind them.

Maya had seen hundreds of such photographs.

As the museum’s curator of southern history, she spent her days cataloging the visual remains of Charleston’s past, sorting through the carefully constructed images that wealthy families left behind.

Most told the same story: power, status, and the careful erasure of those who made such lives possible.

She was about to move on to the next item when something caught her eye.

A glint in the mirror.

A shadow that didn’t quite match the room’s geometry.

Maya zoomed in on the mirror’s reflection, her heart rate quickening.

The digital enhancement revealed what the naked eye would have missed for over a century.

A figure standing behind the camera, a black man, perhaps in his 30s.

His face partially visible as he leaned over the large format camera.

His expression was one of intense concentration, his hands adjusting the equipment with practiced precision.

That’s impossible, Maya whispered to herself.

In 1900, Charleston, black photographers were virtually unheard of in mainstream historical records.

The few who existed worked in the shadows, serving their own communities.

Their names rarely preserved, their work seldom credited.

Yet here was undeniable evidence, captured accidentally in a mirror’s reflection, of a black artist whose skill had been trusted by one of Charleston’s prominent white families.

Maya sat back in her chair, her mind racing.

Who was this man? How had he come to photograph the Whites? And more importantly, what other stories had been hidden in plain sight, waiting for someone to look closely enough to see them? She reached for her phone.

This discovery was just the beginning.

Maya spent the next morning in the museum’s basement archive, surrounded by decades of accumulated documents, photographs, and ledgers.

The climate controlled room hummed with the sound of dehumidifiers, preserving the fragile paper memories of Charleston’s past.

She had barely slept, her mind consumed by the image of the man in the mirror.

She started with city directories from 1895 to 1905, running her finger down columns of names and occupations.

The directories were segregated, as everything had been in that era, with black residents listed separately and often incompletely.

Under photographers, she found three white-owned studios prominently featured.

In the colored section, there were no photographers listed at all.

“Of course not,” Maya muttered, closing the directory with more force than intended.

“Her colleague, James, appeared at the archive door with two cups of coffee.

” “You’ve been down here since 7,” he said, handing her one.

“What’s got you so obsessed?” Maya turned her laptop toward him, showing the enhanced image of the reflection.

James leaned in, his eyes widening.

“Is that who I think it is?” “A black photographer in 1900 working for the Whitmore family,” Maya confirmed.

“I need to find out who he was.

” James pulled up a chair.

“The Whites kept meticulous records.

They donated their papers to the university library years ago.

Have you checked there?” Amaya shook her head.

“That’s my next stop.

” An hour later, she stood in the special collections room of the university library, wearing white cotton gloves.

As she carefully turned the pages of the Whitmore family ledger, the entries were written in elegant script, purchases, payments to servants, social events.

She found the date of the photograph, April 15th, 1900, and scanned the surrounding entries.

There, a single line, payment for portrait services, $3 a s Crawford.

Maya’s pulse quickened.

S Crawford, a name.

Finally, a name.

She moved to the library’s genealological database, searching for Samuel Crawford, Steven Crawford, Simon Crawford.

The results came slowly, each one a dead end or wrong person.

Then, buried in a census record from 1900.

She found him.

Samuel Crawford, 32, occupation listed as laborer, living on Street in a predominantly black neighborhood.

Laborer.

The census taker hadn’t even recorded his true profession.

Maya photographed the entry, her hands trembling slightly.

Samuel Crawford had been invisible in his own time, his artistry hidden behind a generic occupation, but she could see him now, captured in that mirror’s reflection, and she was determined to bring his story into the light.

Maya drove through Charleston streets the next morning, her GPS leading her to the area once known as the Street corridor.

The neighborhood had changed dramatically over 124 years.

Some buildings renovated into expensive condos, others still bearing the weathered dignity of their original construction.

She parked in front of number 47 where Samuel Crawford had lived according to the census record.

The house was gone, replaced by a small community garden.

An elderly woman tended tomato plants in the corner plot, her movements slow but purposeful.

Maya approached carefully.

Excuse me, ma’am.

I’m Dr.

Robinson from the Charleston Heritage Museum.

I’m researching the history of this block.

The woman looked up, shading her eyes from the morning sun.

History? Well, you’ve come to the right person.

I’m Dorothy.

My grandmother lived on this street her whole life.

Talked about it constantly.

She gestured to a bench under a magnolia tree.

Sit with me a moment.

These old knees need a rest.

As they sat, Mia pulled out her tablet, showing Dorothy the enhanced photograph.

I’m looking for information about a man named Samuel Crawford.

He was a photographer who lived here in 1900.

Dorothy’s eyes lit up with recognition.

Samuel Crawford.

Lord, I haven’t heard that name in years.

My grandmother mentioned him.

Said he was the one who took pictures of folks when nobody else would.

And the white studios wouldn’t serve black customers back then.

You understand? Did she say anything else about him? Dorothy thought for a moment.

She said he had a studio.

Not on this street.

Somewhere he had to keep quiet about white folks didn’t like black men having businesses they didn’t control.

But people knew.

If you wanted your wedding photographed, your baby’s first portrait, you went to Samuel.

She paused.

Grandmother also said he was brilliant and that white families would hire him secretly because his work was better than anyone else’s in Charleston.

Maya felt a chill despite the warm morning air.

Do you know what happened to him where his studio was? That I don’t know, but my cousin Robert might.

He’s been working on our family tree for years, collecting stories.

Has boxes of old papers and photographs in his house.

Dorothy pulled out her phone with surprising dexterity.

Let me call him.

20 minutes later, Maya was driving across town to meet Robert.

Dorothy’s directions written carefully on a piece of paper.

The investigation was expanding, one connection leading to another, each conversation peeling back another layer of history that had been deliberately obscured.

Robert’s house sat in a modest neighborhood north of downtown, a well-maintained bungalow with a porch swing and carefully trimmed hedges.

He answered the door before Maya could knock.

a tall man in his 60s with kind eyes and a historian’s eager energy.

“Dorothy called ahead,” he said, ushering her inside.

“I’ve been pulling out everything I have on the coming street community.

This is exciting.

Nobody’s ever asked about Samuel Crawford before.

” He led her to his basement, transformed into a personal archive.

Plastic storage bins lined the walls, each labeled with family names and date ranges.

A large workt dominated the center, already covered with photographs, letters, and documents.

I’ve been collecting family histories for 30 years, Robert explained, pulling out a chair for Maya.

Most black families in Charleston lost their records.

Fires, floods, families scattered during migration, but something survived.

He opened a particular bin, including these.

Ma’s breath caught as Robert carefully laid out a series of photographs on the table.

Unlike the formal portrait of the Whitmore family, these images showed everyday black life in turn of the century Charleston.

A woman in her Sunday dress standing proudly outside a church.

Children playing in a yard.

A man in workcloing his tools.

A young couple on their wedding day.

Each photograph was mounted on heavy card stock with an embossed stamp in the corner.

S.

Crawford photography.

My god.

Maya whispered, leaning closer.

These are his work.

Robert nodded.

My great great grandmother is in this one, he said, pointing to a wedding photograph.

She married in 1902.

According to family stories, Samuel was the only photographer who would take the time to make everything perfect.

He’d arrange people, adjust the lighting, talk to them until they relaxed.

Most white photographers treated black customers like they were processing criminals, but Samuel treated everyone like they mattered.

Why examined each photograph carefully? The technical quality was extraordinary.

Sharp focus, thoughtful composition, perfect exposure.

These weren’t the rushed and personal images typical of the era.

Each one captured genuine emotion, dignity, and humanity.

There’s more,” Robert said quietly.

He pulled out a leatherbound ledger.

Its pages yellowed but intact.

I found this at an estate sale 5 years ago.

I think it belonged to Samuel.

Why opened the ledger with trembling hands.

Page after page listed appointments, client names, prices, and brief notes.

The entries ran from 1897 through 1903.

She recognized some names from her research on Charleston’s black community, teachers, ministers, business owners, but interspersed among them were other entries written in different ink, almost codelike.

W family, April 15th, 1900.

Three.

Discretion required.

He was photographing white families, too, Ma said, her voice barely above a whisper.

Maya returned to Robert’s house 3 days later with specialized archival equipment.

She had spent every available hour analyzing Samuel’s ledger, cross- referencing entries with city records and family histories.

The pattern was clear.

Samuel had operated two separate businesses.

One serving Charleston’s black community openly.

Another serving white clients who sought his superior skills, but required absolute secrecy.

“I think I found where his studio was,” Maya told Robert, spreading a 1900 map of Charleston across his workt.

She pointed to a narrow alley behind King Street.

This building here, the ledger mentions rear entrance, King Street location multiple times.

I checked property records.

In 1898, a man named Thomas Wright, a black carpenter, owned this building.

I think Samuel rented space from him.

Robert studied the map.

That building still exists.

It’s a boutique now, but the structure is original.

Want to take a look? An hour later, they stood in the alley behind a renovated storefront.

The current owner, a friendly woman named Lisa, had agreed to let them explore the building after Maya explained her research.

The upstairs hasn’t been renovated yet, Lisa said, unlocking a door that led to a narrow staircase.

Previous owner used it for storage.

I’ve been meaning to convert it into office space.

The stairs creaked as they climbed.

At the top, Lisa pushed open a door and they stepped into a long, narrow room with high ceilings and windows facing north, perfect for consistent natural light.

The space was filled with decades of accumulated junk, broken furniture, old boxes, dust covered equipment.

Ma’s trained eye immediately went to the windows.

North-facing light, essential for portrait photography.

Robert was examining the walls.

Look at this.

He pointed to marks on the wooden floor, indentations where heavy equipment had once stood.

These could be from camera tripods.

They spent the next two hours carefully moving boxes and furniture, searching for any trace of Samuel’s presence.

Maya was photographing the window frames when Robert called out from the far corner, “Maya, you need to see this.

” He was kneeling beside a loose floorboard he had pried up.

Beneath it was a hollow space, and inside that space was a metal box, its surface covered in rust and dust.

With shaking hands, Mia lifted the box out.

It was locked, but the lock was old and corroded.

Robert retrieved tools from Lisa downstairs, and together they carefully worked the lock free.

Inside were glass plate negatives, dozens of them, each wrapped carefully in cloth.

Maya held one up to the light from the window, and her heart nearly stopped.

“It was a portrait of a black family, beautifully composed.

Every detail sharp and clear.

Samuel’s signature work.

“There must be 50 plates here,” Robert said, his voice filled with awe.

He hid his negatives.

Maya worked late into the night at the museum’s conservation lab, carefully unwrapping and cataloging each glass plate negative Samuel had hidden.

Each image told a story.

Families dressed in their finest clothes.

Children with serious expressions standing perfectly still for the long exposures.

Elderly men and women whose faces held the memory of slavery and freedom.

Young couples beginning their lives together.

But it was the final plates in the box that made Maya’s breath catch.

These showed white families, the Whitmore among them, but also others prominent Charleston names she recognized from historical records.

Each negative had a small number etched in the corner corresponding to coded entries in Samuel’s ledger.

She was documenting the fifth white family portrait when her phone rang.

It was Robert.

“I couldn’t sleep,” he said.

I kept thinking about Samuel hiding those plates.

“Why would he do that? Why not keep them in his studio?” Maya had been wondering the same thing.

I think he was protecting them and maybe protecting himself.

These portraits of white families, if anyone had discovered he was keeping copies, making a record of his work for them, they would have destroyed him,” Robert finished quietly.

A black man with evidence of his artistry, proof that white folks needed his skills.

That would have been dangerous.

Maya looked at the negatives spread before her.

He documented everything.

He created an archive of black Charleston life that otherwise wouldn’t exist.

But he also kept proof of his own excellence, hidden away where no one could deny what he had accomplished.

The next morning, Maya reached out to descendants of the families in the photographs.

She started with the black community, posting on local history forums and contacting churches that had existed since the turn of the century.

The response was overwhelming.

Within days, her office was filled with people bringing their own family photographs, many with Samuel’s embossed stamp.

Each visitor added pieces to the puzzle.

Samuel had been self-taught, learning photography through trial and error.

He had saved money working at the docks to buy his first camera.

He had been known for his patience and his eye for beauty.

He had never married, dedicating himself entirely to his craft.

An elderly man named Mr.

Thomas brought a particular treasure, a letter his grandmother had kept, written by Samuel himself in 1902.

Maya read it aloud, her voice trembling.

Dear Mrs.

Thomas, I hope this portrait brings you joy.

When I look through my camera, I see not just faces, but souls.

I see strength and grace and dignity that the world tries to hide.

Every photograph I take is my way of saying, “You existed.

You mattered.

You were beautiful.

” They may not write our names in their history books, but I will capture our light, and someday someone will see.

Maya knew the next phase of her investigation would be delicate.

She had documented Samuel’s work for Charleston’s black community.

But the white families presented a different challenge.

She needed to approach them carefully, understanding that acknowledging a black photographers’s superior skills would complicate the narratives many families had constructed about their heritage.

She started with the Whites.

The current family patriarch, Richard Whitmore, was a retired attorney known for his involvement in historic preservation.

Maya called his office and explained her research, emphasizing the historical significance of the photograph.

They met at his law office downtown.

its walls lined with family portraits spanning generations.

“Richard was in his 70s, impeccably dressed with the careful courtesy of old Charleston society.

” “Dr.

Robinson,” he said, shaking her hand.

“You’ve piqued my curiosity.

We’ve had that portrait for generations, but I can’t say we’ve studied it closely.

” “Mia showed him the enhanced image on her tablet, zooming in on the mirror’s reflection.

” Richard leaned forward, adjusting his glasses.

“A black photographer,” he said slowly.

in 1900 photographing my great great-grandparents.

He was quiet for a long moment.

That’s not a narrative I grew up hearing.

“Your family paid him $3,” Maya said, showing him the ledger entry.

“That was expensive for the time.

They sought him out specifically.

” Richard sat back in his chair.

“My great great-grandfather was a perfectionist.

Family stories say he fired three photographers before finding one who could meet his standards for that portrait.

He looked at the image again.

I suppose he found what he was looking for, even if he couldn’t publicly acknowledge where.

Would you be willing to have this displayed? My asked, to have Samuel Crawford’s work recognized.

Richard was silent for a long time.

I could see the internal struggle.

Generations of carefully maintained family pride wrestling with historical truth.

Finally, he spoke.

My grandson is biracial.

He’s 12, and he’s been asking questions about our family history.

Difficult questions about race and privilege.

I’ve been struggling with how to answer him honestly.

He looked at Maya directly.

Yes, display it.

Tell Samuel Crawford’s story.

My family benefited from his talent while denying him recognition.

That’s a truth we need to acknowledge.

Over the following weeks, Mia contacted six other families whose portraits she had found in Samuel’s hidden collection.

The responses varied.

Two families refused to participate.

One hung up on her, but three others, like Richard Whitmore, agreed to acknowledge the truth.

One woman, descended from the original clients, wept when she saw Samuel’s reflection in the mirror.

My whole life I was told our family built everything ourselves,” she said.

“But we didn’t, did we? We built it on the backs and talents of people we refused to name.

” Maya stood in the museum’s main gallery 8 weeks later, overseeing the final preparations for the exhibition.

The walls had been painted a soft gray, and professional lighting illuminated the photographs arranged chronologically around the room.

At the center was the Whitmore family portrait, enlarged to show both the formal pose and the enhanced mirror reflection showing Samuel at work.

The exhibition title, in elegant letters above the entrance, read, “Samuel Crawford, the photographer, hidden in plain sight.

” James helped her position the final display case, which held Samuel’s ledger, his camera equipment that Robert had helped her track down from various sources and some of his glass plate negatives.

Each photograph in the exhibition was accompanied by the stories Mia had collected, not just dates and names, but the memories and meanings behind the images.

The black community portraits occupied one wing, showing Samuels documented work.

families in their Sunday finest, children with solemn faces, elderly former slaves whose eyes held lifetimes of stories.

Each image radiated dignity and humanity.

The other wing displayed what Maya had titled the secret commission, the portraits of white families, each shown with their original images and the evidence of Samuel’s involvement.

Explanatory panels described the paradox of his position.

Trusted for his superior skills, but required to remain invisible, paid for his artistry, but denied public credit.

Dorothy arrived early, bringing her entire extended family.

She stood before the exhibition entrance with tears streaming down her face.

My grandmother would have been so proud.

She always said Samuel deserved recognition.

Robert brought more relatives and friends from the coming street community.

They moved through the gallery slowly, pointing out faces they recognized from family albums, reading Samuel’s words, seeing themselves reflected in history.

When Richard Whitmore arrived with his family, there was a moment of tension.

two communities that had existed in separate historical narratives suddenly occupying the same space.

But Richard walked directly to Dorothy and extended his hand.

“Thank you,” he said simply, “for preserving these stories, for making sure the truth could be told.

” Dorothy took his hand.

“Thank you for having the courage to acknowledge it.

” Richard’s grandson stood before the enlarged portrait of his ancestors, staring at Samuel’s reflection in the mirror.

“He was really good,” the boy said, his voice filled with genuine admiration.

better than the photographers today.

Even Maya smiled.

That simple observation, free of the weight of history and prejudice, was perhaps the truest assessment of Samuel’s talent.

As the doors opened to the public, Mia felt the weight of months of research lifting.

She had given Samuel Crawford what he had been denied in life: recognition, acknowledgement, and his rightful place in Charleston’s history.

The exhibition exceeded every expectation.

Local media covered the opening with the story quickly picked up by national outlets.

Headlines read, “Forgotten photographers’s genius revealed after 124 years, and a mirror reflection unveils hidden black artistry in Jim Crow South.

” Maya found herself giving interview after interview, explaining how she had discovered Samuel’s reflection, traced his identity, and uncovered his hidden archive.

But she always redirected attention to Samuel himself, his skill, his courage, his determination to create beauty and preserve dignity in an era designed to deny both.

The museum’s visitor numbers tripled.

People came from across the country, many bringing their own family photographs to compare with Samuel’s work.

The exhibition touched something deep in Charleston’s consciousness, a recognition that history was more complicated, more interconnected, and more painful than the sanitized versions previously told.

Robert became an unofficial curator, spending days at the museum sharing the stories he had collected.

He stood beside the photographs of his own ancestors, telling visitors about the grandmother who had told him about Samuel, about the community that had supported his work, about the networks of trust and secrecy that had allowed a black artist to practice his craft despite the restrictions of his time.

But not everyone celebrated the exhibition.

Maya received angry emails accusing her of rewriting history, of diminishing Charleston’s heritage, of making white families look bad.

One local blogger wrote a scathing piece titled Enough with the Guilt Trip, arguing that Samuel had been treated well for his time and that modern activists were projecting contemporary values onto the past.

Maya addressed these criticisms in a public lecture at the museum.

This isn’t about guilt, she told the Pact auditorium.

It’s about accuracy.

It’s about seeing the whole picture, not just the parts that make us comfortable.

Samuel Crawford was excellent at his craft.

White families recognized that excellence enough to pay him and trust him with their family portraits.

But they couldn’t publicly acknowledge him because of the racial hierarchy of the time.

Both things are true.

Both things matter.

She paused, looking out at the diverse crowd.

When we hide these stories, when we pretend the past was simpler than it was, we lose something essential.

We lose the truth about human resilience, about talent that persisted despite barriers, about the complexity of how people actually lived.

Samuel deserves to be remembered not as a symbol, but as an artist whose work speaks for itself.

The applause that followed was thunderous.

Scholars began arriving to study Samuel’s photographs, recognizing their value beyond the story of their creation.

His technical skills, his composition, his ability to capture genuine emotion all marked him as a master of early photography.

Comparisons were made to contemporaries like James Vander and the emerging black photographers of the Harlem Renaissance.

Though Samuel had worked a generation earlier and in far more restrictive circumstances, six months after the exhibition opened, Mia stood once again in the gallery, but this time for a different purpose.

The museum had acquired the building where Samuel’s studio had been located, and they were unveiling plans to restore it as a working photography space and educational center focused on documenting underrepresented communities in the South.

The Samuel Crawford Center for Visual History would offer free photography classes, archive community photographs, and support emerging photographers from marginalized backgrounds.

It would be everything Samuel Studio had been, a place where people could be seen, documented, and celebrated, but without the need for secrecy or fear.

Dorothy cut the ribbon, her hands steady despite her age.

“Samuel would have loved this,” she said, her voice carrying across the crowd.

Not because it honors him, though I think he’d be pleased about that, but because it continues what he started, making sure people are seen, making sure they matter.

Maya had received an unexpected gift the week before, a package from a family in Philadelphia.

Inside was another glass plate negative found in an attic, showing Samuel himself, the only known photograph of the photographer.

He stood in his studio, one hand resting on his camera, his expression serious, but with a hint of pride visible in his eyes.

He was younger than Mia had imagined, perhaps in his late 20s, already a master of his craft.

That photograph now occupied a place of honor in the exhibition.

Samuel Crawford, finally visible, finally credited, finally home.

As Maya locked up the museum that evening, she thought about the chain of coincidences that had led to this moment.

A mirror positioned just right, a family’s decision to donate an old photograph, her own curiosity that made her zoom in just a little further.

One small reflection had opened a window into an entire hidden world.

She thought about Samuel working in that upstairs studio, carefully preparing his plates, adjusting his camera, talking to his subjects until they relaxed enough to be themselves.

She thought about him hiding those negatives, creating an archive he might never see recognized, but doing it anyway because the work itself mattered.

History had tried to make Samuel Crawford invisible, to reduce him to a generic occupation in a census record, to erase his name from the work he had created.

But he had left clues.

A reflection in a mirror, carefully preserved negatives, a meticulous ledger.

He had believed that someday someone would see.

Maya turned off the gallery lights, leaving only the soft illumination on the photographs themselves.

In the darkness, Samuel’s work glowed.

Faces from more than a century ago, captured with such skill and care that they seemed almost alive.

All those souls he had photographed, given dignity and permanence through his art.

They had existed.

They had mattered.

They had been beautiful and now finally the world could

News

🚛 HIGHWAY CHAOS — TRUCKERS’ REVOLT PARALYZES EVERY LAND ROUTE, KHAMENEI SCRAMBLES TO CONTAIN THE FURY 🌪️ The narrator’s voice drops to a biting whisper as convoys snake through empty highways, fuel depots go silent, and leaders in Tehran realize this isn’t just a protest — it’s a nationwide blockade that could topple power and ignite panic across the region 👇

The Reckoning of the Highways: A Nation on the Edge In the heart of Tehran, the air was thick with…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Darkened City: A Night of Reckoning In the heart of Moscow, a city that once stood proud and unyielding,…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Shocking Resurrection: A Hollywood Revelation In a world where faith intertwines with fame, the announcement sent ripples through the…

🎬 “TO THIS DAY, NO ONE CAN EXPLAIN IT” — JIM CAVIEZEL BREAKS YEARS OF SILENCE ABOUT THE MYSTERY THAT HAUNTED HIM AFTER FILMING ⚡ In a hushed, almost trembling confession, the actor leans back and stares past the lights, hinting at strange accidents, eerie coincidences, and moments on set that felt less like cinema and more like something watching from the shadows, leaving even hardened crew members shaken to their core 👇

The Unseen Shadows: Jim Caviezel’s Revelation In the dim light of a secluded room, Jim Caviezel sat across from the…

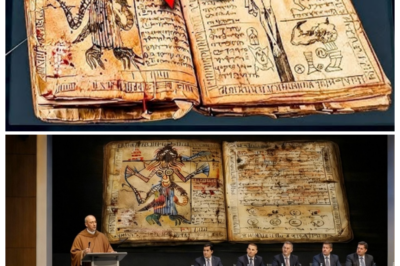

📜 SEALED FOR CENTURIES — ETHIOPIAN MONKS FINALLY RELEASE A TRANSLATED RESURRECTION PASSAGE, AND SCHOLARS SAY “NOTHING WILL BE THE SAME” ⛪ The narrator’s voice drops to a breathless whisper as ancient parchment cracks open under candlelight, hooded figures guard the doors, and words once locked inside stone monasteries spill out, threatening to shake faith, history, and everything believers thought they understood 👇

The Unveiling of Truth: A Resurrection of Belief In the heart of Ethiopia, where the ancient echoes of faith intertwine…

🕯️ FINAL CONFESSION — BEFORE HE DIES, MEL GIBSON CLAIMS TO REVEAL JESUS’ “MISSING WORDS,” AND BELIEVERS ARE STUNNED INTO SILENCE 📜 The narrator’s voice drops to a hushed, dramatic whisper as old notebooks open, candlelight flickers across ancient pages, and Gibson hints that lines never recorded in scripture could rewrite everything the faithful thought they knew 👇

The Unveiling of Hidden Truths In the dim light of his private study, Mel Gibson sat surrounded by piles of…

End of content

No more pages to load