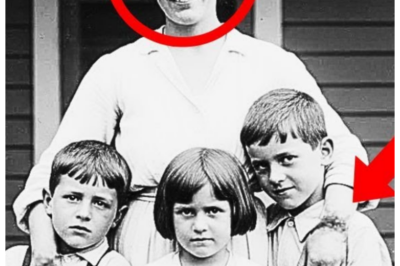

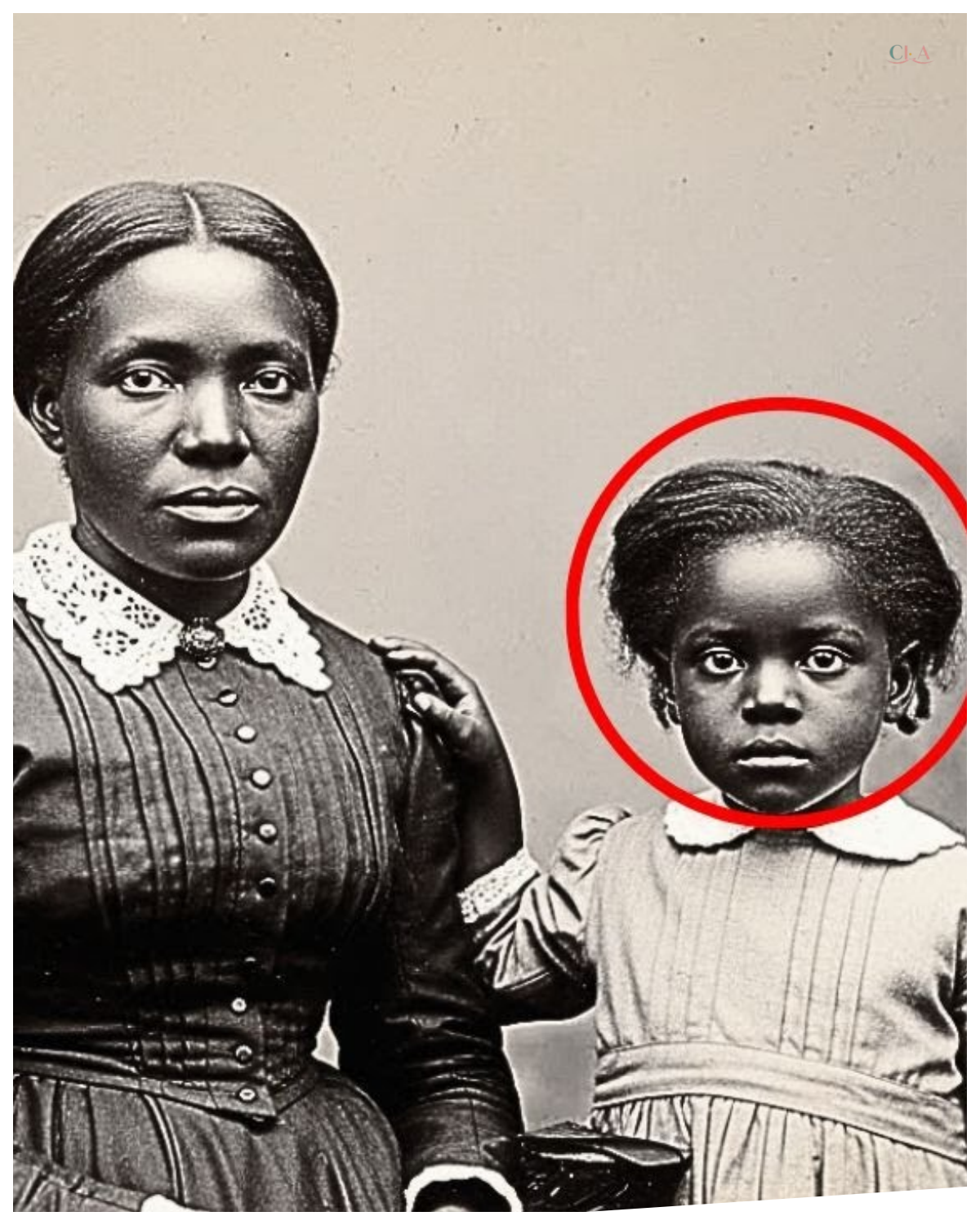

This 1899 portrait of a mother and daughter looks peaceful until you notice what’s hidden in the child’s eyes.

The photograph arrived at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington DC in the spring of 2017.

Part of a larger donation of historical artifacts from a private collector in South Carolina.

It was a simple portrait.

A black woman and her young daughter, perhaps six or seven years old, posed in a photography studio.

The woman sat upright in a wooden chair, her expression dignified but weary, while the child stood beside her, one small hand resting on her mother’s shoulder.

Both wore their finest dresses, carefully pressed and adorned with modest lace collars.

The photograph was dated 1899, taken in Charleston, South Carolina.

Dr.

Jennifer Hayes, a curator specializing in post reconstruction African-American history, was cataloging the donation when she first examined the portrait.

She handled it carefully, noting the photographers’s mark embossed in the corner.

Wesley and Sons photography Charleston SC.

The image was remarkably well preserved.

The sepia tones still rich and clear despite more than a century having passed.

Jennifer set it aside with dozens of other photographs, intending to include it in the museum’s growing collection of late 19th century family portraits.

But something about the photograph nagged at her.

She found herself returning to it throughout the day, studying the faces of the mother and daughter.

There was something in their expressions, particularly the childs, that felt unsettling.

The girl’s eyes were wide and unblinking, staring directly at the camera with an intensity that seemed inappropriate for a child her age.

Her mouth was set in a tight line, not quite a frown, but far from the forced smile many children wore in old portraits.

Jennifer decided to scan the photograph at high resolution, a standard procedure for preserving delicate historical images.

She placed it carefully on the museum’s specialized scanner, adjusting the settings to capture every detail.

The machine hummed softly as it worked, and minutes later, a digital file appeared on her computer screen.

She zoomed in, examining the woman’s face first, the lines around her eyes, the set of her jaw, the careful way her hand rested in her lap.

Then she moved to the child.

Jennifer enlarged the image further, focusing on the girl’s face, and that’s when she saw it.

At first, she thought it was a flaw in the photograph, a spot of damage or discoloration.

But as she zoomed in closer, her breath caught in her throat.

There, reflected in the child’s eyes, barely visible, but unmistakable once you knew to look for it, was an image that didn’t belong.

It was a silhouette, a human figure suspended in the air, dangling from what appeared to be a tree branch.

The reflection was tiny, distorted by the curve of the child’s cornea, but it was there.

Jennifer’s hands began to tremble as the implications settled over her like a weight.

She zoomed in further, adjusting the contrast and brightness, trying to convince herself she was wrong.

But the more she enhanced the image, the clearer it became.

The child had been looking at a lynching, and the photographer had captured it, preserved forever in the reflection of a six-year-old girl’s eyes.

Jennifer couldn’t sleep that night.

She lay in her apartment in Northeast DC, staring at the ceiling, her mind racing through the implications of what she had found.

The image haunted her, not just the horror of the lynching itself, but the fact that a child had witnessed it, that a photographer had captured it, and that it had remained hidden for more than a century, waiting to be discovered.

The next morning, she arrived at the museum early and went straight to the archives.

She needed to know more about Wesley and Son’s photography, the studio that had taken the portrait.

She pulled up the museum’s database of historical businesses in the American South, cross referencing with census records, city directories, and newspaper advertisements from Charleston in the 1890s.

Wesley and Sons had been a prominent photography studio in Charleston from 1887 to 1903, operated by a white photographer named Edmund Wesley and later his two sons, Thomas and Robert.

The studio advertised services for all manner of portraiture and commemorative photography.

And according to city records, it had served both white and black clientele, though likely in segregated sessions, as was common in the Jim Crow South.

What Jennifer found next made her stomach turn.

In the Charleston newspaper archives, she discovered several references to Edmund Wesley in connection with public events in the late 1890s.

One article from 1897 mentioned that Wesley had been commissioned by local authorities to photograph significant civic gatherings.

Another from 1899 noted that his studio had provided documentary services for various community events.

She dug deeper, searching through digitized records of lynchings in South Carolina during that period.

The documentation was sparse.

Many lynchings went unreported or were deliberately obscured by local authorities, but a few cases had been recorded by anti-ynching activists in northern newspapers.

In August 1899, just weeks before the portrait was dated, a black man named Isaiah had been lynched in Charleston.

The newspaper account was brief and cold.

Isaiah, colored, accused of assault on a white woman, was taken from custody by a mob and hanged.

Authorities are investigating.

No further investigation was ever recorded.

No one was arrested.

The man’s full name was never published, nor was the name of the alleged victim.

It was, Jennifer realized with growing horror, just another entry in the brutal ledger of racial violence that had defined the postreonstruction south.

She pulled up the highresolution image of the portrait again, zooming in on the child’s eyes.

The reflection showed a figure hanging from a tree, and in the background, barely visible, she could make out the shapes of other people, a crowd.

This wasn’t a secret late night murder.

This was a public spectacle, a lynching attended by dozens, perhaps hundreds of people, and Edmund Wesley, or one of his sons, had been there to document it.

Jennifer sat back in her chair feeling sick.

Had Wesley been commissioned to photograph the lynching, or had he simply been there, like so many others, to bear witness to the horror? And how had this portrait, taken on the same day in the same location, ended up with that terrible image reflected in a child’s eyes? She knew she needed help.

This wasn’t just a historical artifact anymore.

It was evidence of a crime, a testimony to violence, and a window into a world of terror that black families had been forced to navigate every day.

Jennifer picked up her phone and called Dr.

Marcus Ellison, a historian at Howard University who specialized in lynching and racial violence in the American South.

If anyone could help her understand what she had found, it was him.

Marcus arrived at the museum 2 days later, his expression grave as Jennifer led him to her office.

She had sent him preliminary scans of the photograph, but he insisted on seeing the original.

She handed it to him carefully, and he held it up to the light, studying it in silence for several minutes.

I’ve seen hundreds of photographs from this period, he said quietly.

Family portraits, studio shots, commemorative images, but I’ve never seen anything like this.

He set the photograph down and looked at Jennifer.

Do you know who they are? The mother and daughter? Not yet, Jennifer admitted.

The donation came with minimal documentation, just a note saying the collection had been found in an estate sale in Charleston.

No names, no family history.

Marcus nodded, his jaw tight.

We need to find out who they were, and we need to understand exactly what happened that day.

Over the following weeks, Marcus and Jennifer worked together to reconstruct the events of August 1899 in Charleston.

They combed through newspaper archives, court records, church registries, and the personal papers of anti-ynching activists who had documented racial violence during that period.

Slowly, a picture began to emerge.

Isaiah, the man lynched in August 1899, had been a farm hand who worked on a plantation just outside Charleston.

He had been accused of making unwanted advances toward a white woman.

Though the evidence was flimsy at best and consisted solely of the woman’s testimony, he was arrested, held for 2 days, and then on the evening of August 14th, a mob of approximately 50 white men stormed the jail, dragged him out, and hanged him from an oak tree in a public square.

The lynching had been announced in advance, advertised through word of mouth and hand bills distributed around the city.

It was, like so many lynchings of that era, a public spectacle, a performance of white supremacy designed to terrorize the black community and reinforce the racial hierarchy of the Jim Crow South.

Witnesses reported that hundreds of people attended, including women and children.

Some brought picnic baskets.

Photographers sold souvenir postcards of the scene afterward.

Marcus found a reference to Edmund Wesley in a personal diary kept by a Charleston minister who had opposed the lynching.

The entry dated August 15th, 1899 read, “The photographer Wesley was present yesterday at the lynching of the colored man Isaiah.

He set up his equipment and took several photographs of the crowd and the victim.

I confronted him afterward and asked how he could participate in such evil.

He said he was merely documenting history.

I told him he was documenting sin.

” Jennifer felt a wave of nausea reading those words.

Wesley had been there, camera in hand, capturing the murder as if it were just another event to be commemorated.

And then, either that same day or shortly after, a black mother and her daughter had come to his studio to have their portrait taken.

“Why would they go to him?” Jennifer asked, her voice shaking.

“Why would a black family go to the studio of a man who had just photographed a lynching?” Marcus was silent for a long moment.

“Maybe they didn’t know.

Or maybe they had no choice.

Wesley might have been the only photographer in Charleston willing to serve black clients.

But there’s another possibility.

He looked at her, his expression dark.

Maybe the mother wanted a record.

Maybe she wanted to preserve what her daughter had seen to document the violence they were forced to witness.

A silent testimony.

Identifying the mother and daughter in the photograph proved to be extraordinarily difficult.

Unlike white families, who often had their portraits cataloged in city directories and society pages, black families in the Jim Crow South left far fewer records.

Births, marriages, and deaths were often unrecorded or recorded in separate, poorly maintained registers.

Photographs were expensive luxuries that few could afford, and those that did exist were frequently lost, destroyed, or discarded over the decades.

Jennifer and Marcus began by searching through census records from 1900, looking for black families in Charleston with young daughters.

There were dozens of possibilities, but without names or addresses.

Narrowing the list was nearly impossible.

They cross- referenced baptismal records from black churches in the area, hoping to find a child born around 1892 or 1893 who might match the girl in the photograph.

Marcus reached out to genealogologists and historians in South Carolina, posting images of the portrait on forums and social media, asking if anyone recognized the faces or had family stories that might provide clues.

The response was overwhelming.

Hundreds of people contacted him, sharing their own family photographs and stories, hoping to help solve the mystery, but none of the leads panned out.

Weeks turned into months.

Jennifer continued her other work at the museum, but the portrait haunted her.

She kept a copy on her desk, glancing at it throughout the day, studying the mother’s exhausted expression in the child’s wide, unblinking eyes.

She felt a growing sense of responsibility.

These women deserve to be known, to be remembered by name, not just as anonymous victims of history.

Then in early November, Marcus received an email from a woman named Patricia Dawson, a retired librarian living in Columbia, South Carolina.

She had seen his post about the photograph and believed she might have information.

Her great-g grandandmother, she wrote, had lived in Charleston in the 1890s and had spoken about witnessing a lynching as a child.

Patricia had a few old family documents, letters, a Bible with birth records, and she was willing to share them.

Marcus and Jennifer drove to Columbia the following weekend.

Patricia greeted them warmly, inviting them into her modest home filled with bookshelves and framed photographs.

She led them to her dining room table where she had laid out several items.

A worn leather Bible, a stack of yellowed letters tied with string, and a small photograph in a cracked frame.

This is my great-g grandandmother, Ada, Patricia said, pointing to the photograph.

It showed a woman in her 60s, her face lined with age, but her eyes bright and sharp.

She passed away in 1964, but I remember her stories.

She talked about growing up in Charleston, about how dangerous it was for black people, especially after reconstruction ended.

Marcus picked up the Bible carefully, opening it to the family records page.

Written in faded ink were names and dates.

Adah Price, born March 12th, 1893, Charleston, SC, daughter of Esther Price and Robert Price.

Jennifer felt her heart race.

Do you have any photographs of Ada as a child? Patricia shook her head.

Just that one, and it was taken much later, but she hesitated, then reached for one of the letters.

My grandmother kept this.

It’s a letter A wrote to her when she was older, talking about her childhood.

Let me read you a part.

She unfolded the brittle paper and began to read.

Mama took me to the photographer in the summer of 1899.

I didn’t want to go.

I had seen something terrible the day before, something I couldn’t forget.

But Mama said we needed the photograph, that it was important.

She said someday people would need to know what we survived.

Patricia handed the letter to Jennifer, who read it with trembling hands.

The handwriting was shaky but legible.

written in dark blue ink on paper that had yellowed with age.

Ada had written it in 1958, five years before the march on Washington during a period when the civil rights movement was gaining momentum and old wounds were being reopened.

The letter continued, “I was 6 years old when I saw them hang that man.

” Mama tried to cover my eyes, but I had already seen.

He was innocent.

Everyone knew it, but no one would say so out loud.

The white folks came from all over town to watch.

They cheered when he stopped moving.

I had nightmares for years afterward.

Mama said we had to be strong, that we couldn’t let them see us break.

The next day, she took me to the photographer’s studio.

I remember the man who took our picture.

He had been there, too, at the hanging.

I recognized his camera.

Mama must have known, but she didn’t say anything.

She just held my hand and told me to look straight at the camera to let them see what they had done to us.

Marcus sat back in his chair, his eyes closed.

“She remembered,” he said quietly.

“She remembered everything.

” Jennifer looked at Patricia.

Did Aida ever talk to you directly about this? About what she saw? Patricia nodded slowly.

When I was a teenager, I asked her about growing up in the South during Jim Crow.

She didn’t want to talk about it at first, but eventually she told me.

She said that day, the day of the lynching, changed her forever.

She said she stopped being a child that day, that something inside her broke.

But she also said it made her understand that silence was complicity.

That’s why she joined the NAACP later in life.

Why she marched and protested and refused to be quiet.

She said she owed it to that man, to his memory.

Jennifer carefully examined the photograph Patricia had of elderly Ada, comparing it to the face of the child in the 1899 portrait.

The eyes were the same, wide, intense carrying a depth of emotion that seemed too heavy for such a young face.

“This is her,” Jennifer said with certainty.

“This is Ada.

” Marcus was already searching through the documents looking for any mention of Ada’s mother, Esther.

He found a marriage certificate from 1888.

Esther Johnson, age 19, married to Robert Price, age 24, Charleston SC.

There was also a death certificate for Robert, dated 1897.

He had died of pneumonia 2 years before the photograph was taken, leaving Esther to raise Ada alone.

So Esther was a widow, Marcus said, while supporting herself and her daughter in Charleston in the 1890s.

That must have been incredibly difficult.

Patricia pulled out another document, a faded receipt from Wesley’s son’s photography, dated August 16th, 1899, the day after the lynching.

It was made out to Mrs.

Esther Price.

Payment received for one family portrait, $2.

50.

Jennifer stared at the receipt, her mind racing.

$2.

50, a significant sum for a widowed black woman in 1899.

Esther had spent that money, perhaps money she desperately needed for food or rent to have this portrait taken.

Why? What had driven her to go to that studio to face the man who had photographed her community’s trauma and to immortalize her daughter’s pain? She was documenting it, Marcus said, as if reading Jennifer’s thoughts.

She couldn’t speak out.

That would have been suicide in Charleston in 1899.

But she could do this.

she could take her daughter to that studio and have their portrait made, knowing that someday someone might look closely enough to see what was hidden there.

It was an act of resistance.

Patricia wiped tears from her eyes.

My great-grandmother lived until she was 71 years old.

She saw the civil rights movement, saw black people finally fighting back against Jim Crow.

I think she would be glad to know that her story is finally being told.

With Ada and Esther now identified, Marcus and Jennifer returned to Charleston to locate the exact site where the lynching had occurred.

Historical records indicated it had taken place in a public square near the center of town, but the city’s landscape had changed dramatically over the past century.

Buildings had been demolished and rebuilt, streets had been widened, and parks had been redesigned.

They started at the Charleston County Public Library, searching through old city maps and photographs from the 1890s.

A reference librarian named Thomas, an elderly black man who had lived in Charleston his entire life, recognized the location immediately when they showed him the historical descriptions.

That would be Hampton’s Square, he said, pointing to a spot on an 1895 map.

It’s not there anymore.

They tore it down in the 1920s and built a parking lot.

But my grandfather told me stories about that square.

He said terrible things happened there.

Marcus and Jennifer drove to the location that afternoon.

It was, as Thomas had said, now a parking lot serving a modern office building.

Cars sat in neat rows where the oak tree had once stood, where Isaiah had been murdered, where hundreds had gathered to witness and celebrate his death.

There was no historical marker, no acknowledgement of what had happened here.

Jennifer stood in the middle of the parking lot, feeling the weight of erasure.

They wanted everyone to forget, she said.

They wanted to bury this, to act like it never happened.

That’s why Esther’s photograph is so important, Marcus replied.

It’s proof.

It’s a testimony that can’t be erased.

They spent the rest of the day interviewing elderly residents of Charleston, asking if anyone remembered stories about the lynching or about Hampton Square.

Most people were reluctant to talk, uncomfortable with dredging up such painful history.

But one woman, Mrs.

Dorothy Hughes, age 89, invited them into her home and shared what her grandmother had told her.

“My grandmother was there that day,” Mrs.

Hughes said, her voice quavering.

“She was just a girl, maybe 10 years old.

Her mama brought her because, well, because that’s what people did back then.

White folks wanted black folks to see what would happen if we stepped out of line.

” My grandmother said she never forgot the man’s face, how scared he looked, how he kept saying he was innocent.

She said she saw a woman in the crowd with a little girl, and the woman was crying, trying to pull her daughter away, but the crowd was too thick.

She always wondered what happened to that little girl, whether she was okay.

Jennifer felt chills run down her spine.

“The woman and the girl? Do you think that was Esther and Ada?” “Could have been.

” Mrs.

Hughes said, “There were a lot of black folks there that day, not because we wanted to be, but because we didn’t have a choice.

If you didn’t show up, folks might think you were sympathizing with the victim, and that could get you killed, too.

So, we went and we watched, and we tried not to let them see us cry.

” Marcus leaned forward.

“Mrs.

Hughes, do you know what happened to Isaiah’s body after the lynching?” She shook her head sadly.

“Nobody knows.

” They cut him down eventually, but there was no funeral, no burial that anyone recorded.

His family, if he had any, probably couldn’t claim the body without putting themselves at risk.

He just disappeared like so many others.

But back in Washington, Jennifer and Marcus worked to piece together a complete narrative of what had happened in Charleston in August 1899.

They now had names, dates, locations, and testimonies.

What they didn’t have, and what they desperately wanted, was justice, or at least recognition.

Marcus began drafting an article for the Journal of Southern History, documenting their findings and analyzing the photograph as a unique form of resistance and testimony.

Jennifer, meanwhile, started planning an exhibition at the museum that would center on Esther and Ada’s portrait, contextualizing it within the broader history of lynching and racial terror in the postreonstruction south.

As they worked, they continued to receive messages from people across the country, descendants of lynching victims, historians, activists, and ordinary citizens who were moved by Ada’s story.

One message came from a filmmaker in Atlanta who wanted to create a documentary about the photograph and the investigation.

Another came from a group of high school students in Charleston who were researching local history and wanted to erect a memorial at the site of Hampton Square.

But not all the responses were positive.

Jennifer received several angry emails from people who accused her of stirring up old hatreds and demonizing the South.

One message, unsigned and vicious, read, “That man got what he deserved.

You people need to stop dragging up the past and move on.

Jennifer deleted the message, but it stayed with her.

The photograph had become more than a historical artifact.

It was a flashoint, a reminder that the past was never really past, that the violence and trauma of Jim Crow still echoed in the present.

One evening, as she was preparing to leave the museum, Jennifer received a phone call from Patricia Dawson.

Patricia’s voice was excited, breathless.

“I found something,” she said.

“I was going through more of Ada’s things, and I found a diary.

She kept it during the last years of her life.

And there’s an entry about the photograph.

Jennifer grabbed a pen.

What does it say? Patricia began reading.

January 15th, 1963.

I am an old woman now, and my memory is not what it was.

But I remember that day in 1899 as clearly as if it were yesterday.

I remember the heat, the smell of sweat and fear, the sound of the crowd.

I remember my mother’s hand gripping mine so tightly it hurt.

I remember looking up at that man hanging from the tree and thinking, “They killed him for nothing.

” And I remember the photographer, the white man with his camera, capturing it all like it was a celebration.

When mama took me to his studio the next day, I wanted to run.

But she told me, “We have to do this, baby.

We have to let them see what they did.

” I didn’t understand then, but I do now.

That photograph, my eyes, they hold the truth.

And someday when I’m gone, someone will look close enough to see it.

Jennifer felt tears streaming down her face.

Ada had known.

She had understood, even as a child, that her mother was creating a record, a testimony that would outlast them both.

There’s more, Patricia said.

Ada wrote that she wanted the photograph to be made public someday, that she wanted people to know what happened.

She said, “If my suffering can help someone understand, then it wasn’t for nothing.

” Jennifer wiped her eyes.

We’re going to honor that, Patricia.

We’re going to make sure everyone knows.

The exhibition titled Witness: A Child’s Eyes and the Truth They Hold opened at the National Museum of African-American History and Culture in March 2018.

The centerpiece was Esther and Ada’s 1899 portrait displayed in a climate controlled case with specialized lighting that allowed visitors to see the haunting reflection in Ada’s eyes when viewed from the correct angle.

Surrounding the portrait were panels explaining the history of lynching in the American South, the specific events of August 1899 in Charleston, and the story of Esther and Ada Price.

Photographs of Hampton Square as it had looked in 1899 were displayed alongside modern images of the parking lot that now occupied the site.

Excerpts from Ada’s diary and letter were printed on the walls, her words, a powerful testament to survival and resistance.

Marcus gave the opening speech, his voice steady but emotional.

For too long, the history of racial violence in America has been sanitized, minimized, or erased entirely.

We build monuments to the Confederacy while ignoring the thousands of black men, women, and children who were murdered in its shadow.

This photograph, this remarkable, heartbreaking image is a counter monument.

It is evidence that cannot be denied, testimony that cannot be silenced.

Adah Price carried this trauma her entire life, but she also carried the truth.

And now, thanks to her courage and her mother’s foresight, we can finally bear witness to what they survived.

The exhibition drew thousands of visitors in its first week.

People stood in long lines to see the portrait, many of them weeping as they read Ada’s words and examined the reflection in her eyes.

Teachers brought school groups using the exhibition as a teaching tool about the realities of Jim Crow and the importance of confronting difficult history.

Journalists from national publications wrote articles about the discovery, and the photograph went viral on social media, sparking conversations about racial violence, historical memory, and the ongoing struggle for justice.

Patricia Dawson attended the opening with several members of her family, Adah’s descendants, now scattered across the country, but brought together by the rediscovery of their ancestors story.

They stood in front of the portrait, holding hands, tears streaming down their faces.

I wish she could see this, Patricia said to Jennifer.

I wish Aida could know that her story mattered, that people care.

She knew, Jennifer replied.

That’s why she saved the diary, why she kept the photograph all those years.

She knew someday it would matter.

Not everyone was pleased with the exhibition.

A few protesters gathered outside the museum on opening day, holding signs that read, “Stop demonizing our heritage and the past is the past.

” They were vastly outnumbered by supporters, but their presence was a reminder that the wounds of history were far from healed.

Inside the museum, however, the atmosphere was one of reverence and reflection.

Visitors moved slowly through the exhibition, reading every word, studying every image.

Many left comments in a guest book provided by the museum.

One entry written by a young black woman from South Carolina read, “Thank you for telling the story.

Thank you for making sure Ada is remembered.

We are still here because of women like her.

” In the months following the exhibition’s opening, the impact of Ada’s photograph extended far beyond the museum walls.

In Charleston, a coalition of community activists, historians, and local officials came together to discuss how to properly memorialize the site of Hampton Square.

After months of debate and public hearings, the city council voted to install a historical marker at the location, acknowledging the lynching of Isaiah and the broader history of racial terror in Charleston.

The marker unveiled in November 2018 read, “On this site, formerly known as Hampton Square, Isaiah, surname unknown, was lynched by a mob on August 14th, 1899.

He was one of thousands of African-Americans murdered during the era of racial terror that followed reconstruction.

This marker stands as a testament to those who suffered and died and as a commitment to truth and reconciliation.

Amarcus and Jennifer attended the unveiling ceremony along with Patricia Dawson and several of Ada’s descendants.

The event was somber but powerful with speeches from civil rights leaders, local ministers, and descendants of lynching victims from across South Carolina.

A local gospel choir sang, “Lift every voice and sing.

” And the crowd stood in silence for several minutes honoring the dead.

Jennifer noticed that not everyone in attendance was supportive.

A small group stood at the back, arms crossed, faces hard, but they were outnumbered by those who had come to bear witness, to acknowledge the truth, and to commit to building a more just future.

The photograph also inspired changes in education.

School districts in South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama began incorporating lessons on lynching and racial terror into their curricula, using Ada’s story as a primary source.

Teachers reported that students were deeply moved by the photograph, that it made the history real in a way textbooks never could.

Marcus received an email from a high school teacher in Atlanta.

I showed my students the photograph today.

We spent the entire class period discussing it.

Several students cried.

One boy said, “I never understood before why people say the past isn’t past.

Thank you for bringing this to light.

” The photograph also caught the attention of the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit organization dedicated to documenting and memorializing victims of racial violence.

They reached out to Jennifer and Marcus asking permission to include Ada’s story in their National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

The memorial, which had opened earlier that year, featured hundreds of steel monuments representing counties where lynchings had occurred, each inscribed with the names of victims.

Jennifer and Marcus agreed, and in 2019, a new panel was added to the memorial featuring Ada’s photograph alongside the names of other lynching victims from Charleston County.

Beneath the image, a plaque read, “Adya Price, witness, born 1893.

saw the lynching of Isaiah in Charleston, SC c August 14th, 1899.

Carried the truth in her eyes and her heart for 71 years.

“May we never forget.

” Patricia stood in front of the memorial on the day it was unveiled, her hand pressed against the cold steel.

“She’s finally at peace,” she whispered.

“They can’t erase her anymore.

” 5 years after the discovery of the photograph, Jennifer sat in her office at the Smithsonian, reflecting on everything that had transpired.

The exhibition had closed after its initial run, but had traveled to museums across the country, Atlanta, Birmingham, Memphis, Los Angeles, bringing Ada’s story to millions of people.

The photograph had been reproduced in textbooks, featured in documentaries, and studied by scholars around the world.

It had become, in many ways, one of the most important pieces of evidence of racial terror in American history.

But for Jennifer, it was more than that.

It was a reminder of why she had become a historian in the first place.

to uncover hidden truths, to give voice to the silenced, to ensure that the past was not forgotten or sanitized, but confronted honestly and courageously.

She thought about Esther Price, the widowed mother who had scraped together $250 to have a photograph taken, who had walked into the studio of a man who had documented her community suffering and insisted on being seen.

She thought about Ada, the six-year-old girl whose childhood had been stolen by violence, who had carried that trauma for 71 years, but had never stopped fighting for justice.

Marcus had gone on to write a book about lynching and visual testimony with Adida’s photograph on the cover.

It had won several awards and was now required reading in many college history courses.

He called Jennifer regularly, sharing new discoveries and leads, other photographs, other stories, other voices waiting to be heard.

Patricia Dawson had become an advocate for truth and reconciliation, working with schools and community organizations to teach about racial violence and its lasting impact.

She often gave talks about her great-g grandandmother, showing Adida’s photograph and reading from her diary.

We can’t change the past, she would say.

But we can choose how we remember it, and we can choose to do better.

The photograph itself remained in the Smithsonian’s collection, preserved in a temperature-cont controlled vault when not on display.

It had been digitized and made available online, allowing researchers, educators, and descendants to access it freely.

Every month, Jennifer received messages from people who had seen it.

Some sharing their own family stories, others simply expressing gratitude that the truth was being told.

Well, one afternoon, Jennifer received a letter from a young girl in Charleston, a 12, who had seen the exhibition during a school field trip.

The letter read, “Dear Dr.

Hayes, thank you for showing us Ada’s photograph.

My teacher said that history is about more than dates and names.

It’s about people and their stories.

Ada’s story made me understand that.

I want to be a historian like you when I grow up, so I can help tell the stories that need to be told.

Thank you for not forgetting.

Jennifer pinned the letter to her bulletin board next to a copy of the 1899 portrait.

She looked at Ada’s face, the wide haunted eyes, the small hand resting on her mother’s shoulder, the invisible reflection that held such terrible truth, and felt a profound sense of gratitude and responsibility.

Esther and Ada had done their part.

They had created a record, preserved a testimony, entrusted the truth to the future.

Now, it was Jennifer’s generation’s responsibility to honor that trust, to keep telling the story, to ensure that the victims of racial terror were remembered not as statistics or abstractions, but as human beings, loved, mourned, and deserving of justice.

The photograph would endure.

The truth would endure.

And as long as people like Jennifer, Marcus, and Patricia continued to fight for it, the memory of those who suffered would never be erased.

Adah’s eyes would always bear witness.

News

It was a portrait of love — until you look closely at the mother’s hands

It was a portrait of love until you look closely at the mother’s hands. The afternoon light filtered through dusty…

This 1899 family portrait was restored, and a secret was only revealed now

This 1899 family portrait was restored, and a secret was only revealed now This 1899 family portrait was restored, and…

This 1902 wedding portrait looked beautiful — until experts realized the groom had hidden it

This 1902 wedding portrait looked beautiful — until experts realized the groom had hidden it October 2019, the Smithsonian’s National…

🔥 FAITH SHOCK — POPE LEO XIV DROPS A BOMBSHELL STATEMENT, AND CHRISTIANS WORLDWIDE ARE FUMING ⛪ The narrator snarls as pews erupt in whispers, social media ignites with outrage, and sacred traditions tremble under a single, unthinkable declaration, leaving cardinals scrambling to contain the fallout 👇

The Silent Revelation: When Faith Shattered In the heart of a bustling city, where the clamor of life drowned out…

🔥 SHOCK IN THE PEWS — POPE LEO XIV ABOLISHES CONFESSION TO PRIESTS, DEMANDS DIRECT REPENTANCE TO GOD, AND MILLIONS ARE FURIOUS ⛪ The narrator snarls as clergy scramble, parishioners gasp mid-prayer, and centuries of sacred ritual vanish overnight, leaving the faithful questioning everything they thought they knew about forgiveness 👇

The Shocking Revelation: A Tale of Faith and Redemption In the heart of a bustling city, where the cacophony of…

End of content

No more pages to load